1

WaterResearchCommission

Submitted to:

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Project team:

Mahlathini Development Foundaction(MDF)

Erna Kruger

Temakholo Mathebula

Betty Maimela

Nqe Dlamini

Institute of Natural Resources (INR)

Brigid Letty

Environmental and Rural Solutions (ERS)

Nickie McCleod, Sissie Mathela

Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD)

Derick du Toit

Project Number: C2022/2023-00746

Project Title: Dissemination and scaling of a decision support framework for CCA for smallholder

farmers in South Africa

Deliverable No.6: Case studies: encouraging community ownership of water and natural resources access

and management.

Date: 28 February 2024

Deliverable

6

2

Table of Contents

1.Introduction...................................................................................................................................3

2.Process planning and progress to date..........................................................................................5

Smallholder farmers in climate resilient agriculture learning groups............................................6

Communication and innovation.....................................................................................................9

Multistakeholder platforms...........................................................................................................9

3.Community owned water access guidelines and case studies.....................................................10

3.1Preamble.............................................................................................................................10

3.2Introduction........................................................................................................................12

3.3Problem Statement.............................................................................................................12

3.4Legislative Framework........................................................................................................13

3.5Rural Water Service Provision Experiences in South Africa................................................16

a.KwaZulu Government Regional Councils............................................................................16

b.Non-Government Organisations.........................................................................................17

c.Collaborative government-led approach............................................................................18

3.6Community based management models and approaches.................................................19

a.Self-supply...........................................................................................................................19

b.Co-managed water supply options.....................................................................................20

3.7Guidelines...........................................................................................................................20

a.Approaches and methodologies.........................................................................................20

b.Governance considerations................................................................................................21

3.8example: Co-management of water supply services..........................................................27

3.9Case examples Community owned water schemes............................................................45

3.10Recommendations..............................................................................................................61

a.Governance considerations................................................................................................62

3.11References..........................................................................................................................64

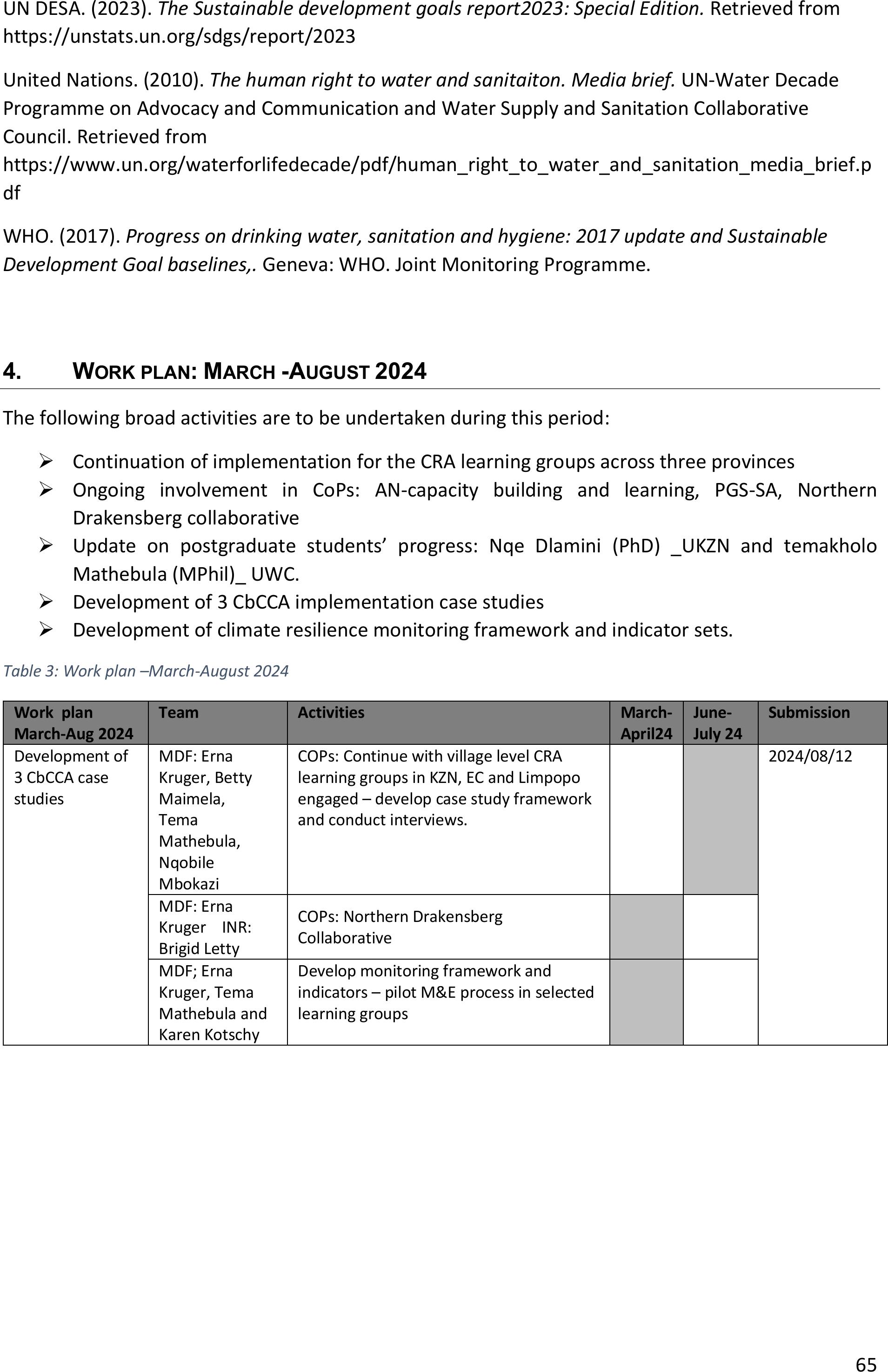

4.Work plan: March -August 2024..................................................................................................65

3

1.INTRODUCTION

This section provides a brief summary of the project vision, outcomes and operational details.

OUTCOME

Vertical and horizontal integration of this community- based climate change adaptation (CbCCA)

model and process leads to improved water and environmental resources management,

improved rural livelihoods and improved climate resilience for smallholder farmers in communal

tenure areas of South Africa.

EXPECTED IMPACTS

1.Scaling out and scaling up of the CRA frameworks and implementation strategies lead to

greater resilience and food security for smallholder farmers in their locality.

2.Incorporation of the smallholder decision support framework and CRA implementation into

a range of programmatic and institutional processes

3.Improved awareness and implementation of appropriate agricultural and water

management practices and CbCCA in a range of bioclimatic and institutional settings

4.Contribution of a robust CC resilience impact measurement tool for local, regional and

national monitoring processes.

5.Concrete examples and models for ownership and management of local group-based water

access and infrastructure.

AIMS

No

Aim

1.

Create and strengthen integrated institutional frameworks and mechanisms for

scaling up proven multi-benefit approaches that promote collective action and

coherent policies.

2.

Scaling up integrated approaches and practices in CbCCA.

3.

Monitoring and assessment of environmental benefits and agro-ecosystem

resilience.

4.

Improvement of water resource management and governance, including

community ownership and bottom-up approaches.

5.Chronology of activities

1.Desktop review of CbCCA policy and implementation presently undertaken in South

Africa

2.Set up CoPs:

a.Village based learning groups: A minimum of 1-3 LGs per province will be

brought on board.

b.Innovation platforms: 3 LG clusters, one for each province consisting of a

minimum of 9- 36 LGs will be identified to engage coherently in this research

and dissemination process.

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Engage existing multistakeholder platforms such as

the uMzimvubu catchment partnership, SANBI- Living Catchments Programme,

the Adaptation Network, etc.

4

3.Develop roles and implementation parameters for each CoP

a.Village based learning groups: CCA learning and review cycles, farmer level

experimentation, CRA practices refinement, local food systems development,

water and resource conservation access and management and participation and

sharing in and across villages.

b.Innovation Platforms (IP): Clusters of LGs learn and share together with local

and regional stakeholders for knowledge mediation and co-creation and

engagement of Government Departments and officials (1-2 sessions annually

for each IP)

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Development of CbCCA frameworks,

implementation processes (including for example linkages to IDPS and disaster

risk reduction planning and implementation at DM and LM level), reporting

frameworks for the NDC to the CCA strategy, consideration of models for

measurement of resilience and impact (1- 2 sessions annually for each multi

stakeholder platform)

4.Cyclical implementation for all three CoP levels (information provision and sharing,

analysis, action, and review) within the following thematic focus areas: Climate resilient

agriculture practices, smallholder microfinance options, local food systems and

marketing and community owned water and resources access and conservation

management plans and processes. Each of these thematic areas is to be led by one of

the senior researchers and a small sub-team.

5.Monitoring and evaluation: Consisting of the following broad actions:

a.Focus on 3-4 main quantitative indicators e.g. water productivity, production

yields, soil organic carbon and soil health.

b.Indicator development for resilience and impact and

c.Exploration of further useful models to develop an overarching framework.

6.Production of synthesis reports, handbooks and process manuals emanating from steps

1-4 withthe primary aim of dissemination of information.

7.And refinement of the CbCCA decision support platform, incorporating updated data

sets and further information form this research and dissemination process.

DELIVERABLES

N

o.

Deliverable Title

Description

Target Date

Amount

1

Desk top review for CbCCA

in South Africa

Desk top review of South African policy,

implementation frameworks and

stakeholder platforms for CCA.

01/Aug/2022

R100 000,00

2

Report: Monitoring

framework, ratified by

multiple stakeholders

Exploration of appropriate monitoring

tools to suite the contextual needs for

evidence-based planning and

implementation.

02/Dec/2022

R100 000,00

3

Handbook on scenarios and

options for successful

smallholder financial

Summarize VSLA interventions in SA, Govt

and Non-Govt and design best bet

implementation process for smallholder

microfinance options.

28/Feb/2022

R100000,00

5

services within the South

Africa

4

Development of CoPs and

multi stakeholder platforms

Design development parameters, roles

and implementation frameworks for CoPs

at all levels, CRA learning groups,

Innovation and multi stakeholder

platforms; within the CbCCA framework.

04/Aug/2023

R133000,00

5

Report: Local food systems

and marketing strategies

contextualized - Guidelines

for implementation

Guidelines and case studies for building

resilience in local food systems and local

marketing strategies towards sustainable

local food systems (local value chain)

08/Dec/2023

R133000,00

6

Case studies: encouraging

community ownership of

water and natural resources

access and management

Case studies (x3) towardsproviding an

evidence base for encouraging community

ownership of natural resource

management through bottom-up

approaches and institutional recognition

of these processes.

28/Feb/2024

R134000,00

7

Case studies: CbCCA

implementation case studies

in 3 different agroecological

zones in SA

CbCCA implementation case studies in 3

different agroecological zones within

South Africa

12/Aug/2024

R133000,00

8

Refined CbCCA decision

support framework with

updated databases and CRA

practices

Refined CbCCA DSS database and

methodology with inclusion of further

viable and appropriate CRA practices

13/Dec/2024

R133000,00

9

Manual for implementation

of successful

multistakeholder platforms

in CbCCA

Methodology and process manual for

successful multi stakeholder platform

development in CbCCA

28/Feb/2025

R134000,00

1

0

Final Report

Final report: Summary of all findings,

guidelines and case studies, learning and

recommendations

18/Aug/2025

(Feb 2026)

R400000,00

Deliverable6 focusses on an analysis of the historical and present institutional and governancefactors

in rural water supply systems and arguments for promotion of community managed and owned water

access systems with a number of case studies to outline learnings and potential examples as

prototypes for implementation.

2.PROCESS PLANNING AND PROGRESS TO DATE

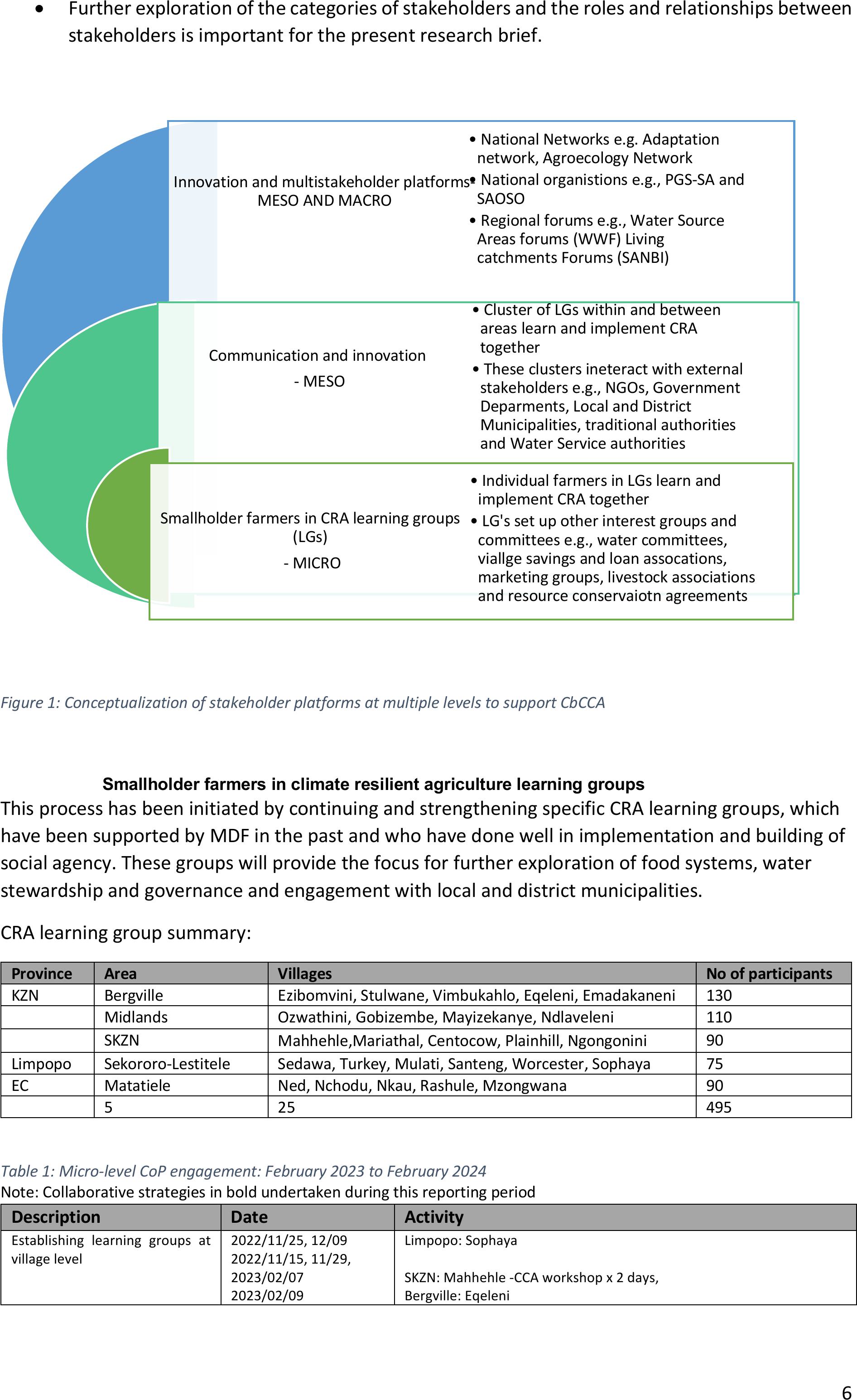

The intention is threefold, as describe below and shown in the diagram:

•Expand introduction and implementation of the CbCCA DSS framework within the areas of

operation of MDFwith a number of different communities. Work with existing communities

as the basis of the case studies in specific thematic areas.

•Introduce and implement the CbCCA DSS framework with a range of other role-players

expanding into new areas, including different agroecological zones and

•Work at multistakeholder level to introduce the methodology as an option for adaptation

planning and action, both within civil society and also including Government stakeholders.

This is the first step towards institutionalization of the processand will involve mainly working

within existing multistakeholder platforms and networks as the starting point.

6

•Further exploration of the categories of stakeholders and the roles and relationships between

stakeholders is important for the present research brief.

Figure 1: Conceptualization of stakeholder platforms at multiple levels to support CbCCA

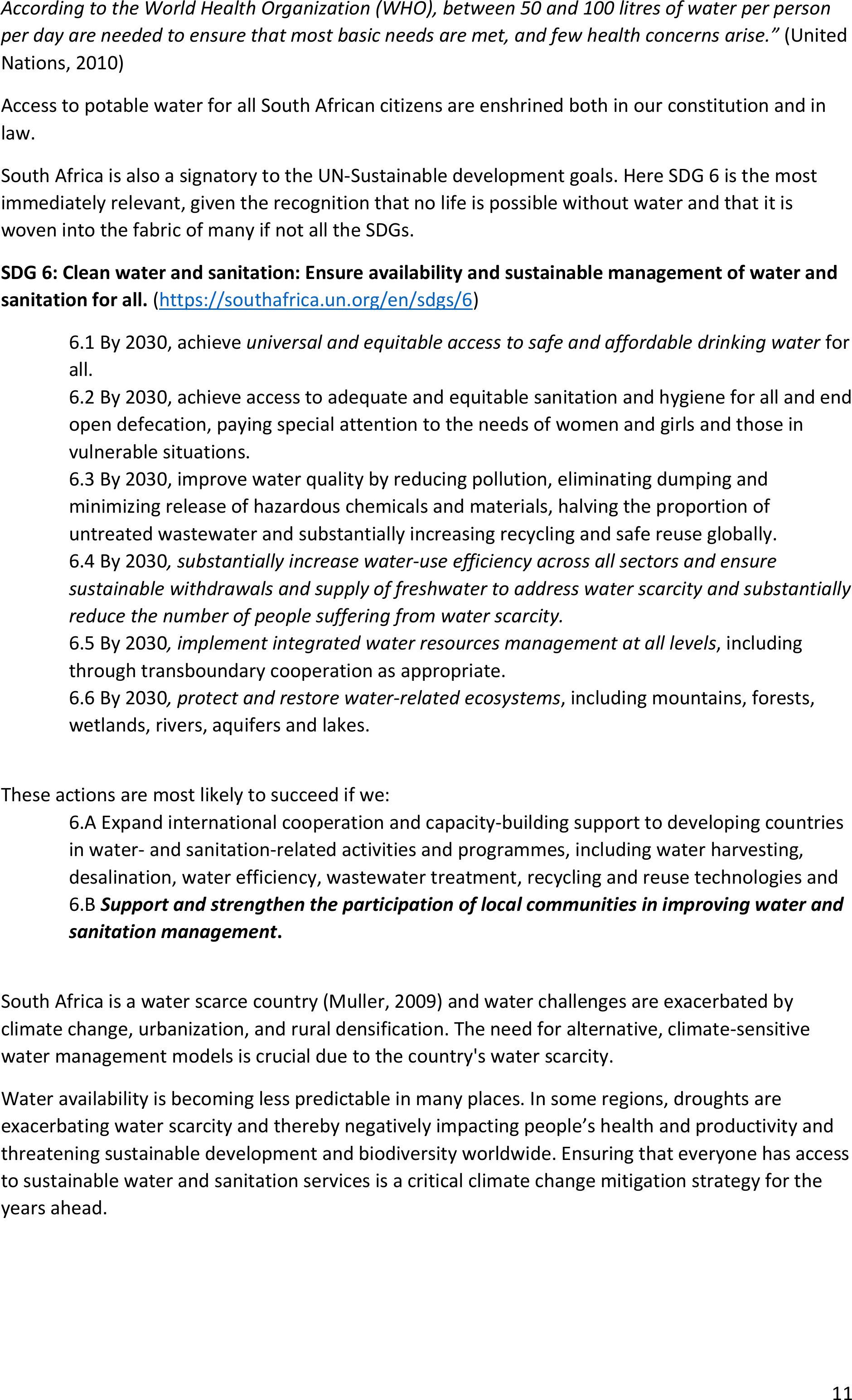

Smallholder farmers in climate resilient agriculturelearning groups

This process has been initiatedby continuing and strengthening specificCRA learning groups,which

have been supported by MDF in the past and whohave done well in implementation and building of

social agency. These groups will provide the focus for further exploration of food systems, water

stewardship and governance and engagement with local and district municipalities.

CRA learning group summary:

Province

Area

Villages

No of participants

KZN

Bergville

Ezibomvini, Stulwane, Vimbukahlo, Eqeleni, Emadakaneni

130

Midlands

Ozwathini,Gobizembe, Mayizekanye, Ndlaveleni

110

SKZN

Mahhehle,Mariathal, Centocow, Plainhill, Ngongonini

90

Limpopo

Sekororo-Lestitele

Sedawa, Turkey, Mulati, Santeng, Worcester, Sophaya

75

EC

Matatiele

Ned, Nchodu, Nkau, Rashule, Mzongwana

90

5

25

495

Table 1: Micro-level CoP engagement:February 2023to February 2024

Note: Collaborative strategies in bold undertaken during this reporting period

Description

Date

Activity

Establishing learning groups at

village level

2022/11/25, 12/09

2022/11/15, 11/29,

2023/02/07

2023/02/09

Limpopo: Sophaya

SKZN: Mahhehle -CCA workshop x 2 days,

Bergville: Eqeleni

Innovation and multistakeholder platforms-

MESO AND MACRO

Communication and innovation

-MESO

Smallholder farmers in CRA learning groups

(LGs)

-MICRO

•National Networks e.g. Adaptation

network, Agroecology Network

•National organistions e.g., PGS-SA and

SAOSO

•Regional forums e.g., Water Source

Areas forums (WWF) Living

catchments Forums (SANBI)

•Cluster of LGs within and between

areas learn and implement CRA

together

•These clusters ineteract with external

stakeholders e.g., NGOs, Government

Deparments, Local and District

Municipalities, traditional authorities

and Water Service authorities

•Individual farmers in LGs learn and

implement CRA together

•LG's set up other interest groups and

committees e.g., water committees,

viallge savings and loan assocations,

marketing groups, livestock associations

and resource conservaiotn agreements

7

2023/01/18

2023/03/27

2023/06/15, 07/07

EC: Ned, Nkau

Limpopo: Madeira

KZN Midlands: Ndlaveleni, Montobello, Noodsberg, Inkuleleko primary

school

Training and mentoring for

climate resilient agriculture

2022/12/02

2022/10/26

2022/10/08-14

2022/11/23,24,29

2022/02/10

2022/02/27, 03/28

2022/03/08, 03/17,

03/28

2022/03/15

2023/03/07,08

2023/03/29,30

2023/03/24,27,30

2023/04/, 2023/05,

2023/06

2023/04/21,25, 05/26,

06/08

2023/04/19,20

2023/06/22

2023/08/07,08,10

2023/09/19

2023/10/16-19

2023/11/13-17

Midlands: Ozwathini contouring workshop SKZN: Mahhehle – tower

gardens

EC-Matatiele: Dripirrigation workshops in 5 villages

SKZN: CA demonstration workshops in 3 villages

SKZN: Plainhill Drip irrigation training

Limpopo: Sofaya trench beds

SKZN: Mahhehle tower gardens, poultry production, trench beds

SKZN: Mariathal gardens and experimentation

Bgvl: Madakaneni, Mahlathini– gardening training

EC: Ned, Nchodu poultry production

EC: Nec, Nchodu, Mzongwana- Pest and disease control

Limpopo and KZN: trench bed training with assembling of tunnels for 45

households across 8 villages, including distribution of seedlings, mixed

cropping and mulching learning inputs and drip irrigation

Limpopo: Willows, Sedawa, MametjaSophaya. Bergville-Matwetha,

Emadakaneni – Natural Pest and Disease control

Bergville, SKZN: Poultry production: eMadakaeneni, Mjwetha, Mariathal,

Mahhehle,Centocow

EC: Ned, Nkau, Rashule, Nchodu- Soil and water conservation

Matatiele: Multipurposechicken production and cage construction

(Ned(13), Rashule(22), Nchodu(23)

Matatiele: Nchodu -Value Adding training (32)

Limpopo: Boschvelder feeding and management training x 5 villages (50

participants)

Limpopo (30): CA demonstrations and farmer level experimentation:

intercropping cover crops

Cyclical implementation through

mentoring for capacity

development for LG at local level

2022/08/16,17,18,19,30

2022/10/16

2022/11/21-24

2023/01/24-30

ONGOING

2023/10/03-06

2023/11/05-12/15

2023/11/30-2024/02/28

CCA review and planning workshops

-Bergville: CA review and planning (5)

-Midlands: CA review and planning (3)

-Limpopo: CCA review and planning (4)

CCA prioritization of practices

-Matatiele: 5 villages (Ned, Nchodu, Rahsule, Nkau, Mzongwana

-All areas: garden monitoring, poultry support,tunnel and drip kit

installations,VSLAs monthly meetings, CA production and monitoring

KZN-Bergville Boschvelderchicken delivery and maintenance mentoring

for 45 participants

KZN: Bergville_CA farmer experimentationplanting for 124

participants, incl cover cropsawa collaboration with Forge Agri to

Fodder Beet trials and Zylem SA for new Maize variety trials

Midlands: Seedling nursery project initiation for youth groupin

Gobizembe (11 members)

Income diversification and

economic empowerment of

local farmers (LG at local level)

2022/10/02,11/03,

12/04,

2023/02/02,03/02,

03/03, 04/03, 05/02,

06/02, 07/04, 08/05,

09/03, 10/05,

2023/09/29

2022/10/08, 11/07,

12/02, 2023/01/27,

02/07, 07/04, 08/05,

09/05

2022/11/05,06,07

2023/01/27

2023/01/26

2022/12/13

2023/02/14

2023/02/14

Jan-December2023

Market days: monthly farmers markets

-Midlands: Bamshela (Ozwathini)

-SKZN: Creighton (Centocow)

-Ubuhlebezwe LED Ixopo flea market

- Bergville: Bergville town

Market exploration workshops

-Midlands: Mayizekanye, Gobizembe

-EC_Ned-Nchodu market day in Matatiele

-SKZN: Mariathal

PGS follow-up w/s Limpopo

SKZN: Mahhehle

VSLA introduction

-SKZN: Mahhehle

VSLA meetings and share outs

-Bergville: 9

-SKZN: Ngongonini (2), Centocow (4)

-Midlands: Ozwathini (6)

8

2023/03/15,16

July-Sept 2023

Limpopo: (7)

Youth tala table value adding training.

-Livelihoods survey- all areas

Implementation and capacity

development for innovation (3)

and multi-stakeholder platforms

(3)

2022/11/18

2022/11/10

2022/12/01

2023/02/23

2023/02/28

2023/03/08,09

2023/03/89,29,

May-July 2023

2023/03/30, 06/02

2023/04/26

2023/05/09

2023/07/10-15

2023/08/18

2023/08/29

2023/08/30

2023/09/04

2023/09/08

2023/09/13

2023/09/22-24

2023/08/23, and 09/27

2023/07-12

-SKZN: Centocow P&D control cross visit and learning workshop

-uThukela water source forum: Visioning and action planning – Bergville

-Adaptation Network AGM

-Regenerative Agric farmers’ day in Bergville incl Asset research,

uThukela Water Source Forum, uThukela Development Agency

-Adaptation Network: CCA financing dialogue

-SANBI_gender mainstreaming dialogue

-WRC-ESS: Bglv Ezibomvini, Stulwane –resource management mapping

and planning

Bergillve:Stulwnae weekly community resource management workdays

-Okahlamba LED forum

-Farmers X visit between Bulwer (supported by the INR0 and Bergville

around CRA, fodder and restoration

-PGS-SA: market training input: Online training Session 5

-Giyani Local Scale Climate resilience Project: Introduction of CCA model

and local water governance options.

-World Vision: CCA workshops for women cooperatives and LED project

(60 participants)

-Giyani Climate resilience project: Input into WRC reference group

meeting

-KZN DARD_ Okahlamba Agricultural Show: display and talk

ACDI: Dialogue on community adaptation and resilience (Stellenbosch)

Food systems article for newsletter

WWF-Business Network meeting (SAPPI Durban)- presentation

Joint Bergville learning group local marketing review session

Gcumisa_multistakeholder innovation meeting – with the INR, ~60

participants (value adding, stokvels and local marketing

Food systems dialogue: online event

Uthukela water source forum: Core team meeting and Multistakeholder

field visit around community resource conservation in Stulwane (Bgvl)

-LIMA -Social Employment Fund: Training for work teams and

employed youth in nutrition, value adding, climate change adaptation

and agroecological gardening practices including soil and water

conservation in 7 areas: Zululand, SKZN, Lichtenburg, Sekororo,Musina

and Blouberg (140 participants trained).

Indicator development for

evidence-based indicators, M&E

and handbook development

2023/01/30- 02/03

2023/02/02

2023/01/18

2023/01/18

2023/02/20

March-May 2023

June 2023

2023/10/16-20, 11/13-

16

Limpopo: Focus Group discussions for VSLA and microfinance for the

rural poor x 3 (Turkey, Worcester, Santeng)

Garden monitoring:

-SKZN: Plainhill

-EC: 5 villages

CA monitoring

-EC:5 villages

-KZN: Bergville -30, Midlands 15, SKZN 15

-All areas: Poultry production list

-All areas: Livelihoods survey for farmgate sales and asset accumulation

-M&E resilience indicatordevelopment team meeting and process with

k Kotschy

Implementation ofsustainable

water management

2023/01/03-02/03

2023/03/07

2023/03/25, 06/15

2023/04/25, 06/01,02,

06/14.

2023/07/26-28,

09/14,10/09-14, 11/06-

10, 12/05-15,

2024/01/21-02/02

KZN: Bergville: Stulwane – Conflictman and upgrading spring protection.

EC: Nkau: Water walk and meetings for spring protection and

reticulation.

KZN: Bgvl Stulwane_ Engineer visits (Alain Marechal) for scenario

development and follow up planning meetings with community. Set up

committee, work parties and start on quotes and budget outline

KZN: Bgvl Vimbukhalo: Governance of communal borehole water supply

KZN: Bgvl Stulwane_ Engineer visits (Alain Marechal) for scenario

development and follow up planning meetings with community. Set up

committee, work parties and start on quotes and budget outline. Work

on scheme initiated.Final implementation of scheme.

Organisational& capacity

development

2022/11/17

2022/12/05

2023/02/13

2023/02/09, 02/16

2023/03/06

-MDF AGM and organisational capacity development workshop

-Mentoringand planning with new finance officer to implement SODI

financial reporting system

- Internal short learning event for rainfall and runoff results, as well as

soil fertility and Organic carbon

- Mentoring in CCA workshop implementation. Temakholo from

Midlands assisted Bergville team

-Team session on gender mainstreaming

9

2023/03/13

2023/04/17

2023/05/26

2023/06/12

2023/07/04

- UKZN- Ecological mapping and use of resource planning – Bgvl team

-VSLAs review and discussion re group based rules, BLF updates

- Nutrient analysis for livestock fodder options: facilitated by Brigid Letty

from the INR

-Small business development support planning and Livelihoods survey

-MDF AGM and organisational capacity development workshop

Communication and innovation

This aspect relates to platforms for sharing and learning with clusters of learning groups (LGs). No

activities were undertaken here between December 2023 and February 2024.

Multistakeholder platforms

To date the research team has participated in a range multistakeholder platforms, networks and

communities of practices (CoPs) towards developing a framework for awareness raising,

dissemination and incorporation of the CbCCA-DSS methodology into local andregional planning

processesand developing methodological coherence for a number of the themes to be explored in

this brief.

In this present period of December 2023- February 2024 only aa few activitieshave been undertaken.

The table below outlines actions and meetings to date.

Table 2: Planning and multi stakeholder interactions for the CCA-DSSII research process: February 2024

Organisation

Activity - Description

Dates

Asset Research-

Maize Trust, SODI

Regenerative Agriculture farmers’ open day in Bergville

Annual Maize Trust CA forum workshop, Bethlehem – MDF

presentation

23rdFeb 2023

10thOctober 2023

ESS research - WRC

UKZN research in ecosystem services mapping supported by MDF:

water walks, focus group discussions, planning, eco-champs, spring

protection work in Stulwane, thematic and mapping workshops in

Ezibomvini and Stulwane, local level planning and implementation.

Cross visit Ezibomvini to Stulwane to see resource management work

Finalisation and handover of maps, updated community resource

management plans for Ezibomvini and Stulwane

Final report preparation and ref group meeting

23rdSeptember 2022

14thOctober 2022

13,29,30 March 2023

1-30thMay 2023

29th September 2023

18th October 2023

22nd November 2023

WWF Watersource

forum

uThukela catchment partnership: Stakeholder meetings, online and in

person at OLM board room Bergville (new name: Northern

Drakensberg Collaborative). Development of vision, membership

profile, constitution and core team and full collaborative meetings

Core team meeting for visioning and constitution development

Multistakeholder field day for community level resource conservation

in Stulwane, Bergville

29thSeptember 2022

10thNovember 2022

11thApril 2023

23rdMay 2023

23rdAugust 2023

28thSeptember 2023

SANBI- Living

Catchment

Programme

Social facilitation capacity building workshop – Western Cape; M

Malinga

Olifants’ water indaba: M Malinga, N Mbokazi, H Hlongwane, B

Maimela and E Kruger

Video on local initiatives in catchment management

3rd-5thOctober 2022

30thOct-2ndNov 2022

24thMarch 2023

SANBI

Climate change adaptation and gender mainstreaming dialogue –

presentation and participation

SANBI newsletter- runoff impacts of restoration and CA

8th-9thMarch 2023

4thJune 2023

Adaptation Network

Policy input and AGM

Ongoing input and involvement in the Capacity development working

group: to implement thenew Civil Society Organisation Skills

Enhancement and Excellence Development (CSO SEED) project,

funded by the Flanders government.Some of these activities include

youth-led participatory videos on adaptation initiatives and some

thematic field visits and exchanges between AN CSO member projects.

13thOctober 2022

1stDecember 2022

7th, 8thFeb 2023

15thMarch 2023

10

3.COMMUNITY OWNED WATER ACCESS GUIDELINES AND CASE STUDIES

By Nqe Dlamini and Erna Kruger

3.1PREAMBLE

Water is a basic human right and a vital resource for health, livelihoods and development. However,

millions of people in South Africa still lack access to safe and reliable water sources, especially in

rural and peri-urban areas. According to the World Health Organization, only 56% of the rural

population and 79% of the urban population had access to at least basic water services in 2017

(WHO, 2017).

According to the United Nations “The water supply and sanitation facility for each person must be

continuous and sufficient for personal and domestic uses. These uses ordinarily include drinking,

personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation and personal and household hygiene.

Meetings with AN to discuss capacity building and outlineCCA training

for Socio technical Interface NGO in Hammanskraal

AN newsletter: Food systems article by Tema Mathebula

An-AGM

11thMay 2023

15thJune 2023

20thSeptember 2023

16thNovember 2023

PGS-SA

Quarterly meeting: Discuss mapping of PGS organisations, finalisation

of certificate and use ofsealsand logos.Finalisation of smallholder

farm assessment form

PGS-Certification working group

Online market development training: Input into session 5

17thNov 2022

13thFeb 2023

9thMay 2023

Okhahlamba LM

Agriculture and Land summit: MDF presentation and marketing stall:

All Bergville staff, farmers representatives and eco champs

Okahlamba LED forum meetings

OLM – support with transport for farmers’ markets and tractors for

field preparation

Okhahlamba Agricultural show

30thNovember 2022

30thMarch 2023,7th

June 2023

Ongoing

29thAugust 2023

Afromontane

research Centre

Maloti-Drakensberg Climate Change Workshop

Wageningen/UFS: Land futures course - Bgvl

12-14 December 2022

7-10thMarch 2023

Water Research

Commission/ AWARD

Giyani Local Scale Climate Resilience Project:

Support for CCA and VSLAs

Water governance andinfrastructure management community

dialoguein Mayephu, Giyani – for development of guidelines and

proof of concept

WRC-Inauguralref grp meeting for: Enterprise development and

innovation for rural water schemes- GLSCRP

8-10thMay 2023

10th-14thJuly 2023

30th-31stOctober 2023

3rdand 29thNovember

2023

Umzimvubu

Catchment

Partnershipand ERS–

Nicky McCleod, Sissie

Mathela

Webinar toreview CRA and spring protection implementation and

plan for future projects

Planning for combined spring protection in Nkau and next deliverable

8thNov 2022

15thJune 2023

AWARD – Derick du

Toit

Meeting in Hoedspruit to discuss AWARD’s contribution

Youth induction programme– Tala Table network

Planning for CRA learning group expansion, Mametja-Sekororo PGS

continuation.

Group marketing review and farm level assessments

2ndNovember 2022

30thJanuary 2023

22ndMarch 2023

8thMay 2023,

29thSeptember 2023

Karen Kotshcy

Learning in M&E interest group meeting. Discussions re methodology

for UCP and Tsitsa project multi stakeholder engagement evaluation

Discussions and MoU development for M&E framework and indicator

developmentand submission of report for WRC deliverable 4.

Development of Climate resilient indicators for CbCCA

11thNovember 2022

15thMay 2023

24thMay 2023

16-20thOctober, 13th-

16thNovember2023

8thFebruary 2024

11

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 50 and 100 litres of water per person

per day are needed to ensure that most basic needs are met, and few health concerns arise.”(United

Nations, 2010)

Access to potable water for all South African citizens are enshrined both in our constitution and in

law.

South Africa is also a signatory to the UN-Sustainable development goals. Here SDG 6 is the most

immediately relevant, given the recognition that no life is possible without water and that it is

woven into the fabric of many if not all the SDGs.

SDG 6: Clean water and sanitation: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and

sanitation for all. (https://southafrica.un.org/en/sdgs/6)

6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking waterfor

all.

6.2 By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end

open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in

vulnerable situations.

6.3 By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and

minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of

untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.

6.4 By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure

sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially

reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity.

6.5 By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including

through transboundary cooperation as appropriate.

6.6 By 2030, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests,

wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes.

These actions are most likely to succeed if we:

6.A Expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries

in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting,

desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies and

6.B Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and

sanitation management.

South Africa is a water scarce country (Muller, 2009)and water challenges are exacerbated by

climate change, urbanization, and rural densification. The need for alternative, climate-sensitive

water management models is crucial due to the country's water scarcity.

Water availability is becoming less predictable in many places. In some regions, droughts are

exacerbating water scarcity and thereby negatively impacting people’s health and productivity and

threatening sustainable development and biodiversity worldwide. Ensuring that everyone has access

to sustainable water and sanitation services is a critical climate change mitigation strategy for the

years ahead.

12

3.2INTRODUCTION

These are proposed guidelines for community-managed rural water supply systems. The main goal

of a community-managed rural water supply system is to provide a community with adequate, safe,

reliable, consistent, equitable and sustainable water in accordance to prevailing national legislation

thus multiple sources of water for multiple use systems.

The purpose of these guidelines is to present a community-based approach which builds alliances

between communities and development agencies and promotes joint actions and social

accountability as a key strategy for providing water services to rural communities. A water service

may include protected springs and wetlands, streams and rivers, borehole hand-pumps or fully-

mechanised piped water systems. Municipalities are obligated by the Water Services Act number

108 of 1997 to provide communities with reliable water services. The right to safe, reliable,

affordable and sustainable access is also enshrined in the constitution of South Africa. However,

municipalities are yet to integrate decentralised and community-based management as one of the

strategies for delivering water services to rural communities.

3.3PROBLEM STATEMENT

“Wherever practical, water services and infrastructure must provide water for multiple use and

accommodate mixed levels of service within communities, allowing consumers to elect a level of

service which suits their needs, is affordable to them (within theprevailing subsidy framework),

addresses inequalities, utilises appropriate and upgradable technologies, and is governed effectively

and responsibly to ensure sustainability.”

Despite this statement in the latest DWS review of water service provision, the legal and regulatory

framework for such implementation has yet to be developed. District and Local Municipalities are

the mandated water service authorities (WSAs) and Water Service providers (WSPs), with Water

Services Committees only possible if the community petition’s the Minister to reinstate the

mechanism.

The water service challenges in rural South Africa since 1994 stem in part from a lack of

collaboration between municipalities and community-based organizations. Municipalities resist

community-based management, hindering decentralized water systems (Buthelezi, 2006).This

reluctance contributes to poor quality, inadequate, unaffordable, and inequitable water access in

rural areas. The first major problem is the reluctance of municipalities to view community

organizations as partners in delivering water services, leading to a reproduction of poverty penalties,

particularly affecting young girls and women who spend excessive time fetching water (Geere &

Cortobius, 2017).

The second issue arises when stand-alone rural water schemes break down for extended periods,

denying communities their constitutional right to safe and reliable water. Despite causes like theft

and vandalism, municipalities are obligated to provide water services. In breakdown situations,

communities resort to alternative sources like springs and rivers, which may lack safety and

affordability.

Historical apartheid geospatial planning in South Africa has left many rural areas without basic

services, and current responses like voluntary migration impact water service planning, financing,

and maintenance. Some schemes may be under-designed for rural densification or overly designed

for communities facing migration. Geospatial disparities in water infrastructure run counter to pro-

poor and broad-based economic goals, exposing rural communities to health risks and loss of

productive time.

13

The implementation of community owned and or co-managed water access schemes and services

still needs to be piloted and tested in different contexts to provide a realistic framework and

process, thus prototypes, for institutionalization and formal recognition of these processes.

Collaborative and co-management options for management of water access presently include a

range of options, that are supported informally at institutional level depending on the will and

orientation of local officials. These include for example:

•Liaison with Ward councillors regarding implementation and management of state provided

infrastructure.

•Employment of local operators through the WSA who are managed at local level by village level

water committees, often linked to the ward councillors and/or the traditional council and a

voluntary water committee.

•Ad hoc maintenance of infrastructure at community level through these voluntary water

committees which include community contributions and local level maintenance.

•Organisation of the local communities into management areas or sections to effect more

participatory maintenance and management and

•Various levels of self-supply options,which include individuals and groups.

There are many positives to communities getting involved in water management, but this

‘involvement’ brings with it a number of challenges. These challenges are not only of the

community’s making but are often entrenched in socio-political and governance systems (Nortje,

Mbhele, Polasi, & Zulu, 2022). Presently Municipal WSAs are primarily concerned with communities

taking more responsibility for operation, maintenance and efficient use of infrastructure provided,

with a secondary concern of cost recovery mechanisms for longer term sustainability. Communities

presently have a greater concern in having access to sufficient water for domestic and productive

use and as such have shown a greater and remarkable willingness to be more involved in co-

management of water supply options. Self-supply options, both on an individual and group level are

already very common in many underserviced rural communities, South Africa and Limpopo

(Hofstetter, van Koppen, & Bolding, 2021), including Giyani.

3.4LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

The policy framework for water service provision in South Africa consists broadly of the Water

Services Act 108 of 1997 (WSA), the National Water Act 36 of 1998 (NWA) and the National

Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA) which make provision forthe regulation and

provision of water services by different state institutions in South Africa. The relevant pieces of

legislation are summarised briefly below:

•The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996), which recognizes the right to sufficient

water and the duty of the state to ensure that everyone has access to water services.

•The National Water Act (1998), which establishes the principles of integrated water resource

management, participatory governance, equity and sustainability, and provides for the

establishment of catchment management agencies, water user associations and other

institutions to facilitate COWA.

14

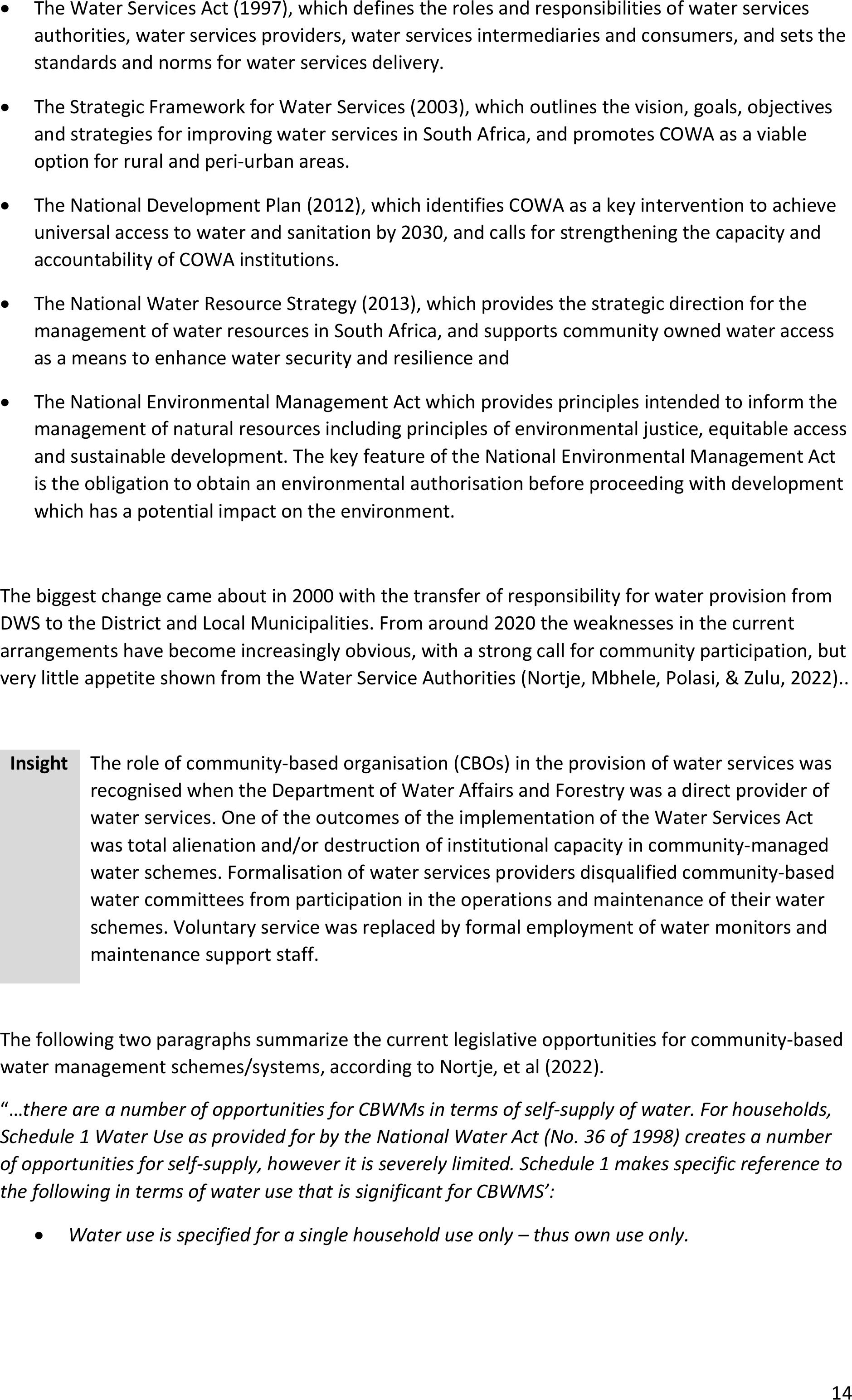

•The Water Services Act (1997), which defines the roles and responsibilities of water services

authorities, water services providers, water services intermediaries and consumers, and sets the

standards and norms for water services delivery.

•The Strategic Framework for Water Services (2003), which outlines the vision, goals, objectives

and strategies for improving water services in South Africa, and promotes COWA as a viable

option for rural and peri-urban areas.

•The National Development Plan (2012), which identifies COWA as a key intervention to achieve

universal access to water and sanitation by 2030, and calls for strengthening the capacity and

accountability of COWA institutions.

•The National Water Resource Strategy (2013), which provides the strategic direction for the

management of water resources in South Africa, and supports community owned water access

as a means to enhance water security and resilience and

•The National Environmental Management Act which provides principles intended to inform the

management of natural resources including principles of environmental justice, equitable access

and sustainable development. The key feature of the National Environmental Management Act

is the obligation to obtain an environmental authorisation before proceeding with development

which has a potential impact on the environment.

The biggest change came about in 2000 with the transfer of responsibility for water provision from

DWS to the District and Local Municipalities. From around 2020 the weaknesses in the current

arrangements have become increasingly obvious, with a strong call for community participation, but

very little appetite shown from the Water Service Authorities (Nortje, Mbhele, Polasi, & Zulu, 2022)..

Insight

The role of community-based organisation (CBOs) in the provision of water services was

recognised when the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry was a direct provider of

water services. One of the outcomes of the implementation of the Water Services Act

was total alienation and/or destruction of institutional capacity in community-managed

water schemes. Formalisation of water services providers disqualified community-based

water committees from participation in the operations and maintenance of their water

schemes. Voluntary service was replaced by formal employment of water monitors and

maintenance support staff.

The following two paragraphs summarize the current legislative opportunities for community-based

water management schemes/systems, according to Nortje, et al (2022).

“…there are a number of opportunities for CBWMs in terms of self-supply of water. For households,

Schedule 1 Water Use as provided for by the National Water Act (No. 36 of 1998) creates a number

of opportunities for self-supply, however it is severely limited. Schedule 1 makes specific reference to

the following interms of water use that is significant for CBWMS’:

•Water use is specified for a single household use only – thus own use only.

15

•Serves to support the use of water for subsistence farmers – thus not for commercial

farming.

•Makes provision for the water of animals that are kept for household use – thus not for

commercial use such as feedlots – and has to be within grazing capacity of the land.

•Stipulates ‘lawful’ use of the resource – thus one has to lawfully have access to the resource

in order for you to make use of the water.

The Water Services Act (No. 108 of 1997) provides a number of opportunities for communities

towards self-supply. However, in this case we find that bureaucratic processes are particularly

hindering and cumbersome, especially for communities if they seek tooperate within the bounds of

the law. Under this Act, communities have two opportunities in terms of self-supply, they can either

become a Water Services Provider (WSP) or act as a Water Services Committee. These two options

bring with them a host of obstacles, in the least currently if a community wants to operate as a WSP

they have to register as a Community-Based Organisation (CBO) while if they want to act as a Water

Services Committee, they need to petition the Minister to reinstate the mechanism”.

For self-supply options the following rules/obligations have been set out for Water service

Authorities:

•The WSA shall advocate augmenting water use with alternative water sources, such as

groundwater (springs, wells, boreholes), rainwater harvesting and stormwater harvesting.

•The relevant regulations and protocols for groundwater and spring protection shall be

applied.

•Water use shall be metered or monitored for reporting and planning purposes.

•Guidelines shall be provided to self-supply households regarding treatment and purification

of alternative water sources for domestic and personal use.

•The WSA shall make available an advisory service to households wishing to self-supply.

•The WSA shall assist with access to good quality products and services regarding self-supply.

•The municipal by-laws shall be revised to allow for self-supply.

•Maintenance of the infrastructure is the responsibility of the owner.

•Point-of-use water treatment systems and methods shall be advocated.

•Users shall be educated in effective water use and hygiene, with a focus on water quality

requirements and water conservation.(Department of Water and Sanitation, 2017)

The new policy environment has created a discrepancy between the legal recognition of the efforts

and capacities of community members and their actual role in water service delivery. Local

politicians and government officials perceive community members as consumers whose role is to

avoid vandalism and to save water, to make it easy for the municipality to implement projects or to

express their wishes in the consultations for the Integrated Development Plan10 (IDP). These same

community members however construct, improve, operate and maintain water infrastructure and

fill the gaps in public service delivery. These schemes vary in complexity, ranging from individual

wells to collectively owned, piped water schemes (Hofstetter, van Koppen, & Bolding, 2021).

16

3.5RURAL WATER SERVICE PROVISION EXPERIENCES IN SOUTH AFRICA

The purpose of this sub-section is to present broad approaches used to provide water services to

rural communities. Management of water resources and water systems by communities goes back

hundreds of years. Communities had ways and systems to govern and operate water resources.

However, modernisation and changing circumstances always present new problems which require

new solutions.

a.KwaZulu Government Regional Councils

Prior to the 1994 South African democratic project, the KwaZulu Government used Regional Councils

to provide services to rural communities. A Regional Council was essential a local government

structure. Traditional authorities constituted the majority of Regional Councils. AmaKhosi in these

Regional Councils had the strongest voices in dictating how community projects were implemented,

operated and maintained.

The significance of this era was the interest shown by international donors and non-governmental

organisations in supporting community development initiatives including water projects. During this

time, water projects included mainly spring protection, small gravity-fed reticulations and borehole

hand-pumps. Establishment of umbrella community-based development committees and project-

specific committees was the order of the day. Non-governmental organisations would collaborate

with Regional Councils in promoting community participation in the delivery of projects. In some

ways, community-based app roaches enabled development agencies to draw from community

knowledge and expertise in resolving some development challenges. Water committees would be

established, trained and capacitated to recruit community labour, participate in project

management decision making, help communities to elect water management volunteers and

provide constant feedback to communities. Defaulters and delinquent community members were

reported to the Traditional Councils and were dealt with accordingly.

However, this era raised many concerns and criticism, from finding the most committed and skilled

volunteers in community organisations, to freeing of community organisations of elitism, patriarchy

and total disregard of the voices of the poor. Obviously, there is considerable interaction between

the community development and the nature of social stratification in any community, and elitism is

a common feature of all societies (Keshava, 1975). During this era, community organisations would

be constituted bypeople aligned to, and closest to the Traditional Councils and the homeland

government. Voices of some professionals and government officials would dominate community

projects. Although some lessons can be drawn from the Regional Councils era, it must be noted that

young adults and the youth today are far different from their parents. Their parents were somehow

conditioned to bow to the authority. In fact, their parents were largely conformist to the authority.

This means that development approaches that worked before the new democratic dispensation in

South Africa are likely to be challenged.

Insight

The issue is not to identify whether community power structures are elitist, but which

community decision-making platforms deliver the services, demonstrate interest to

strengthen participation, and platforms that are able to adapt to challenges and changes

as they unfold. Elitist power structures may be permeable and community groups can

successfully identify patterns and navigate community power structures that are related

to, and favour specific development outcomes (Drew, Francis, & Kenneth, 2001)

17

At the dawn of democracy, the Mvula Trust was established in 1993 to support the Department of

Water Affairs and Forestry to develop affordable and sustainable water services especially for rural

communities of South Africa (Group, 2003)(Buthelezi, 2006)

b.Non-Government Organisations

The general approach by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the water service delivery space

reflects a participatory and sustainable development perspective (Krantz, 2001). The key oitns in this

approach can be summarized as follows.

1.Participatory Approach:

•Emphasizes involving the people who will be using or benefiting from the

development initiative.

•Recognizes the importance of engaging the community in decision-making

processes.

2.Sustainable Development Theory:

•Puts people at the centre of development.

•Acknowledges that local communities understand their vulnerabilities and possess

solutions for the challenges they face.

3.Local Organizations as Development Agents:

•Views local organizations as essential in building and strengthening just and

empowering participation.

•Highlights the role of these organizations in the development process.

4.Sustainable Livelihoods Approach:

•Provides a framework to understand the complexities of poverty and vulnerability.

•Offers principles guiding actions to address poverty and vulnerability.

5.Community-Based Management:

•Focuses on designing community water supply systems based on lived experiences

and community development factors.

•Recognizes the dynamic interaction between the community and various

development institutions.

•Involves both community-based and external development institutions.

•Decentralizes decision-making to maximize community participation in planning,

implementing, and operating water schemes.

6.Tools and Guidelines:

•Collaboration between international and local NGOs, as well as research institutions.

•Development of tools and guidelines for planning, implementation, operation, and

maintenance of water schemes.

7.Key Features of Community-Based Management:

•Iterative nature, indicating an ongoing, flexible process.

•Decentralization of decision-making to the lowest level possible.

•Maximizing community participation in implementing and operating water schemes.

18

•Draws from sustainable livelihood theory, incorporating social feasibility

assessments, considerations of social equity, and specific indicators for sustainable

water schemes.

In summary, the approach integrates the principles of participation, sustainable development, and

community-based management to address water service delivery. The focus on collaboration, local

empowerment, and sustainable practices is crucial for creatingeffective and lasting solutions in the

water sector.

Insight

Community life, lived experiences, shared benefits, social bonds, common values and

shared interest are common concepts that define collective action in many vulnerable

communities, African societies and their institutions. African ways of life do not isolate

constructions of life, everything is connected. Effective and meaningful participation

means that people must define their needs and take decisions that help them solve their

development challenges. Effective participation should acknowledge that malfunctioning

of one or two constructions of life exposes households and communities to vulnerability

hence access to water cannot be seen isolation of many other community realities.

c.Collaborative government-led approach

The "Build, Operate, Train and Transfer" (BOTT) approach was introduced in South Africa in 1997 by

the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry as a public-private partnership (PPP) aimed at

expediting the construction and operation of water and sanitationprojects, particularly in former

homeland areas. BOTT contracts involved collaboration between the state, private sector

institutions (programme implementing agents or PIAs), and regional councils, later transformed into

district municipalities. While intended to improve efficiency, ensure equitable water provision,

empower personnel, and recover costs, BOTT contracts faced criticism for being private sector-

driven, expensive, and overly centralized, weakening local government and non-profit organizations

in the water sector.

The BOTT program's significance lay in its principles of community participation, skills development,

empowerment, and job creation. It aimed to establish community-based water institutions, train

and mentor them during project construction, and transfer water supply projects to these

institutions for operation, maintenance, and tariff collection. However, the implementation of the

Water Service Act of 1997 in 2001 shifted ownership and control to municipalities, leading to

community-based water institutions being marginalized and ill-prepared for the transfer. Criticisms

from civil society organizations and research institutions highlighted the challenges of over-

centralization and the private sector-driven nature of BOTT contracts. Additionally, community-

based management, represented by non-governmental organizations like the Mvula Trust, faced

rejection and criticism from water service authorities, creating historical resentment in the water

sector (Buthelezi, 2006).

19

3.6COMMUNITY BASED MANAGEMENT MODELS AND APPROACHES

Community owned water access (COWA) is a form of decentralized water management that involves

the participation and empowerment of local communities in the planning, implementation,

operation, and maintenance of their own water systems, which can offer several benefits, such as:

•Enhancing the sustainability and resilience of water systems by reducing dependency on

external actors and resources.

•Improving the affordability and accessibility of water services by tailoring them to the specific

needs and preferences of the communities

•Promoting the social and environmental justice of water allocation by ensuring that the rights

and interests of marginalized groups are respected and protected and

•Fostering the social cohesion and empowerment of communities by strengthening their

collective identity, agency, and ownership of their water resources

However, COWA also faces several challenges, such as:

•Lack of adequate technical, financial, institutional, and human capacity to design, construct,

operate, and maintain water systems.

•Lack of clear legal and regulatory frameworks to support and protect the rights and

responsibilities of COWA actors.

•Lack of effective coordination and collaboration among different stakeholders, such as

government agencies, NGOs, private sector, and other communities and

•Lack of sufficient monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to ensure the quality, efficiency, and

accountability of water services.

There are several community-based management models that can be considered for stand-alone

rural water supply schemes. Lessons are drawn from historical publications and informal

conversations regarding rural water schemes. In addition, recent developmentsand attempts at

developing both self-supply and collaborative management options are considered. Small case

studies are provided as examples.

This section considers two options of water services. The first option involves a community

operating a small water supply system (self-supply) without the involvement and support of a water

services authority, that is, a municipality. The second option involves a municipality taking the role of

construction, operation and maintenance of a water scheme in collaboration with a community-

based institution. Our working definitions are summarised below.

a.Self-supply

Despite the rapid extension of public service delivery since the end of Apartheid, many rural citizens

in South Africa still rely on their own initiatives and infrastructure to access water. They construct,

improve, operate and maintain infrastructure of different complexities, from individual wells to

complex collectively owned water schemes. While most of these schemes operate without legal

recognition, they provide essential services to many households (Hofstetter, van Koppen, & Bolding,

2021). Lessons learned from studying such schemes as locally adapted prototypes have the potential

to improve public approaches to service delivery.

These self- supply options show the willingness of community members to engage with service

delivery and their ability to provide services in cases where the state has failed and where bulk

20

supply options for water provision are constrained. They also provide pointers and learning for

collaborate and community co-management of state supplied infrastructure, something that is

crucial for efficiency, equity and long-term sustainability.

Self-supply is 100% user-funded, governed and operated. A community-based and informal

organisation is usually established to deal with governance and operational matters. Water

infrastructure is provided on incremental basis. Users decide on the most appropriate technology,

financing arrangements, cost-recovery strategy and type of services they want. Spring water

protection and small piped water schemes that use gravity to feed small reservoirs are preferred

options.

Historically, a blended self-supply approachwas mainly promoted by non-governmental

organisations and international donors in the community water space which allowed for funding

support for the water schemes. For instance, a rural community would seek support from an outside

development agency, andusually a non-governmental organisation. A non-governmental

organisation would engage community stakeholders, conduct an assessment, confirm water as a

priority need, and prepare a funding application for submission to national and/or international

donors. A community-based water institution would be established when funds have been secured

in preparation for implementation. A community-based water institution would be trained and

capacitated to take some projectmanagement roles as well as operations and maintenance roles

post project completion. The water infrastructure would be managed by a community-based water

institution. However, this approach was more appropriate for small rural communities. This

approach is yet to be tried by municipalities.

b.Co-managed water supply options

Collaborative/co-management water management between communities and mandated

Government stakeholders presently has no legal, structural or process under pinning, but does

happen on an ad hoc basis depending on the personal interest, involvement and commitment of

both government officials and community members and their institutions. There is a growing

movement towards developing guidelines, procedures and case examples toward institutionalising

these approaches.

3.7GUIDELINES

a.Approaches and methodologies

These guidelines promote an alternative institutional mechanism that is built on multi-stakeholder

dialogue, action and accountability at a village level. In this document, we have coined a concept of

village water dialogues(VWD)to describe an alternative and decentralised mechanism for delivering

water services to rural communities. It is an attempt to promote a management mechanism that

would see rural communities collaborating with public organisations.

Village water dialoguesis a non-confrontational advocacy approach that empowers communities to

engage directly with the representatives of public organisations to improve the quality of water and

related services. Village water dialoguesis action and solution oriented where all parties agree on

ways for improving water services and social accountability indicators. It is based on the notion of

active citizenship where citizens and public organisations hold one another accountable in matters

of public service. There are three main phases of village water dialogues.

•The first phase is concerned with community education on citizens’ rights and corresponding

responsibilities, water sector stakeholders and public service communication platforms. This

21

phase is also concerned with strengthening institutional capacity of communities to engage with

public organisations. The main outcome of this phase is an empowered water community

representative institution that is capable of engaging in a constructive dialogue with public

organisations on matters that are related to water services.

•The second phase is the heart of village water dialogues. A community representative structure

engages with public organisations and finds a sustainable solution to resolve water problems in a

community. There are two main outcomes of this phase.The first outcome is a well-packaged

water project and action plan. The second outcome is a social accountability plan which

defines and assigns roles and responsibilities of community members in making a water

project successful and sustainable. Cost recovery is a key component of a community

accountability plan.

•The final phase is concerned with implementation of a water project. During this phase,

community members monitor all the processes that are involved in the implementation,

operations and maintenance of a water project. The main outcome of this phase is a

sustainability plan. The main focus of a sustainability plan is conservation and protection of

water sources and includes the requirements that water supply systems should cause little or

no harm to the ecosystem and should ensure that the needs of futuregenerations are not

compromised. Therefore, a water system is deemed sustainable when it does not over exploit

the water resource and the system is protected to avoid water contamination. In addition, a

community-managed water system is sustainable when it is able to recover operational costs

and is properly operated and maintained to supply adequate uncontaminated water to the

users.

Activities proposed in these phases are essentially calling for the re-integration of community-based

management models into rural water services provision. This call to re-integrate community-based

management is influenced by the fact that communities with no or limited access to safe and

reliable water services are in most cases voiceless and unheard, and consequently revert to

alternative water sources which, in many cases would be polluted. This makes municipalities

transgressors of their constitutionalobligation to supply safe and reliable water to their citizens.

These guidelines aim to promote decentralised water management and fit-for-purpose rural water

systems. A village water dialoguesapproach is employed to facilitate the re-integration of

community-based management in the rural water supply programmes.

b.Governance considerations.

Community level involvement

All members of a community are expected to make use of provided infrastructure and water access

in a responsible manner. For this to be possible all community members need to:

• be considered in terms of their needs,

• be informed about the technical aspects of operation for the system,

• understand the implications and limits of access and availability of water,

• know and agree to the management and operational confines of the system and

• be willing to follow the rules set in place for quality, management and use of water.

The above can only happen if every single member in the community takes some individual

responsibility and considers the impact of their actions on their neighbours and community. In larger

and more urban communities, individual behaviour is controlled primarily through payment for

22

specific services and access, with associated regulations. In rural and informal communities, this

system of control does not exist. This can lead to high levels of inequity, competition, abuse, and

mismanagement of water supply systems.

The temptation is to attempt to enforce payment and regulation of services. The solution however,

lies more in the full participation of all community members in every phase of the process.

Guidelines for community level engagement

Community members need to be engaged in initial baseline, vulnerability and feasibility

assessments for proposed water supply schemes.

Community members need to understand water access options, water sources and availability and

water use implications for their village.

Community members need to be provided with information to be able to assess the proposed

scenarios for development of water access options.

Community members need to be provided space for learning and analysis of concepts related to

water management in their areas, including for example climate change impacts, rainfall and water

infiltration, groundwater and groundwater management, water quality for drinking and

multipurpose use, technical aspects of proposed systems, solar energy, water purification options,

water use and conservation etc., so that they are better able to make informed decisions.

Community members need to develop an understanding of water provision as a service with the

potential for different levels and sources of access for different purposes and different levels of

access to this service dependant on financial and other contributions.

In complex programmes scenarios are developed. These are refined in the planning and

implementation and yet further changes can occur during the contractual and commissioning

phases. Expectations are raised in each phase and community members often remember well what

was “promised’ at the beginning. This process requires careful explanation on an ongoing basis.

NOTE: the tendency is to not provide detail or make specific ‘promises’ to avoid the resultant

conflict, but the better practise is to explain the changes and difficulties as the process unfolds,

which despite being a lot more intensive has the advantage of also increasing community level

understanding of the issues and problems involved and this level of transparency builds trust and

rapport between the role players, as well as a level of accountability in expenditure.

Community members need to engage with and negotiate all parameters of the scheme to be able to

take responsibility for further operation, management and maintenance.

Community members need to be involved in decision making on a day-to-day level and in

selection/election of local water governance structures/committees.

They need to be a part of the process of decision making around beneficiation and equity.

ASSUMPTIONS:

It is possible to make some assumptions on how individuals in rural communities will behave, based

on experiences in engaging these communities in designing, planning and implementing local water

access options, rather than being the passive recipients of externally designed and implemented

water supply systems. These experiences have shown that:

•Community members are willing and able to participate.

23

•Community members are willing to volunteer their time, labour, and money towards

ensuring a functional water system.

•Community members are committed to ensuring that their water supply system is

operational and looked after.

•Community members are willing and able to make rational and considered decisions

around water use and management if provided with appropriate information on which

to base such decisions.

•The actual level of involvement in the operation and maintenance of the system is a

choice for community members. Some members participate by voluntarily following the

rules and others are more involved in the management of the system.

•Levels of water access need to be equitable and transparent.

Guidelinesfor local governance structures

At community level arrangements are more often than not already in place, although they would be

considered informal. Often these arrangements will not fulfil the requirements of the Water Service

Authorities but provide for a level of stability and equitywithin the community.

Water committees are voluntary structures and as such have two major weaknesses:

Members do have a certain level authority within the community but are not able to

effectively police any rules. They cannot control or officially/legally enforce any of the rules

agreed to be the community. As such informal arrangements are developed. Often it relies

on community members contributing in time and in small regular payments to an agreed

activity, such as water infrastructure maintenance or borehole pumping costs for example.

The committee keeps records of those community members who pay and those who do not.

Generally, those community members who resist the rulings or do not pay are considered

not to be part of the process and their opinions or complaints or difficulties are then not

taken into account and

Members of committees can take advantage of their authority to improve their own

beneficiation, often justified as a form of compensation for their efforts. This process, if

managed in a transparent way, could actually assist in providing for longer term

sustainability of committees, as it provides some benefit to the committee members who

often have to deal with many problems, conflicts and complaints on an ongoing basis.

At village level this is a manageable beneficiation system and can allow for a stable and ongoing

operational system, without too much conflict. There is however a chance that vulnerable

households and individuals are excluded from a service which should benefit all community

members. Households with very high levels of poverty are more often than not also households

where members engage in socially high risk and unacceptable behaviours, which ostracises them

from the rest of the community. Other prejudicesmay also surface, especially around unmarried

women with children and ‘foreigners’. It is proposed that this process be externally facilitated, as it is

unlikely that communities themselves will design systems that are fully equitable.

Traditional councils can fulfil a valuable function of oversight, providing coherence and conflict

management support at community level. This has not traditionally been one of their functions, but

can fit well into the suite of functions, services and support they provide to their communities. Such

ideas however will however need to be negotiated and institutionalised

24

Local water committees

Care needs to be taken to ensure that these committees are well represented and should include

representation from:

ØThe traditional ward councils

ØThe Local ward councils (Local Municipality)

ØLocal representatives of the Water Service Authority and providers

ØMembers form local development structures and interest groups, including for example the

livestock association, development committees, farmers associations and groups,

cooperatives, churches, schools and creches and

ØLocal household members; both with access to individual water supply options (like

boreholes and springs) and without.

These committees need well developed constitutions with roles and responsibilities outlined

therein. These committees also need to have arrangements in place for operations and maintenance

of the water service in their village as well as security of infrastructure.

Security concerns for infrastructureare a reality and something that water committees invariably

will need to deal with. Local security arrangements are important and are already being more

commonplace, both for infrastructure and for livestock. In some villages in Giyani, including

Mayephu, 24hr patrols have already been put in place to monitor and control theft. It is foreseeable

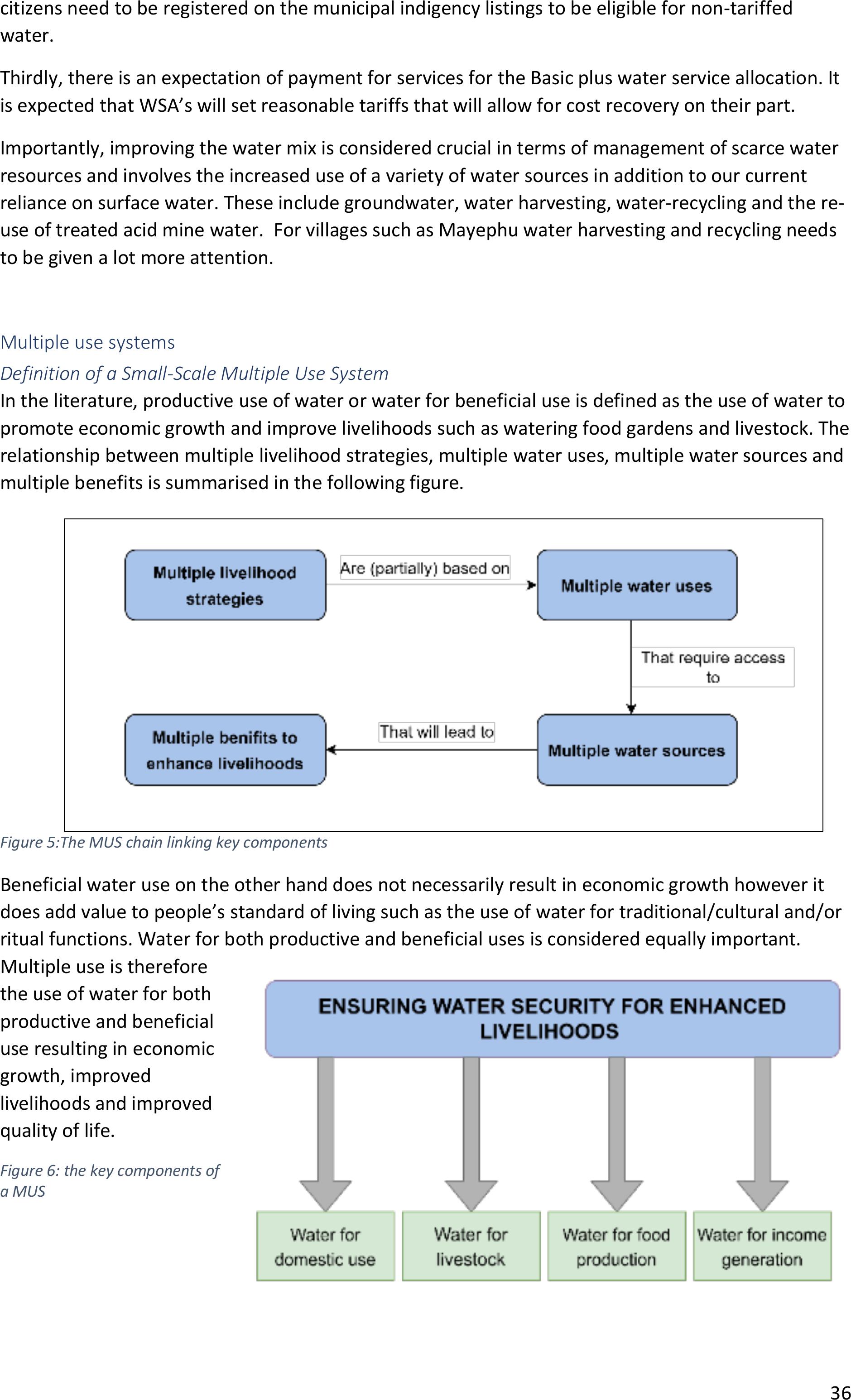

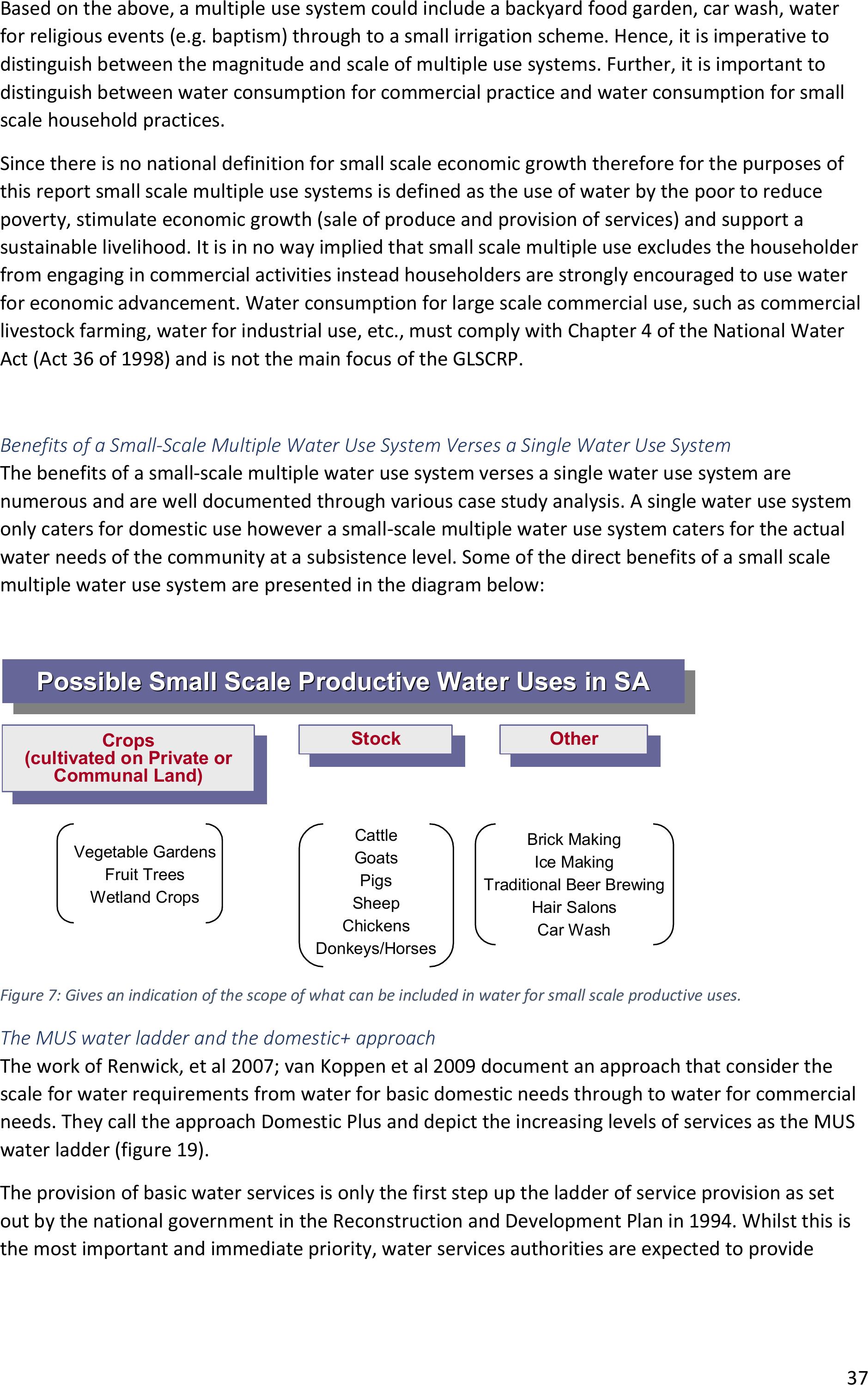

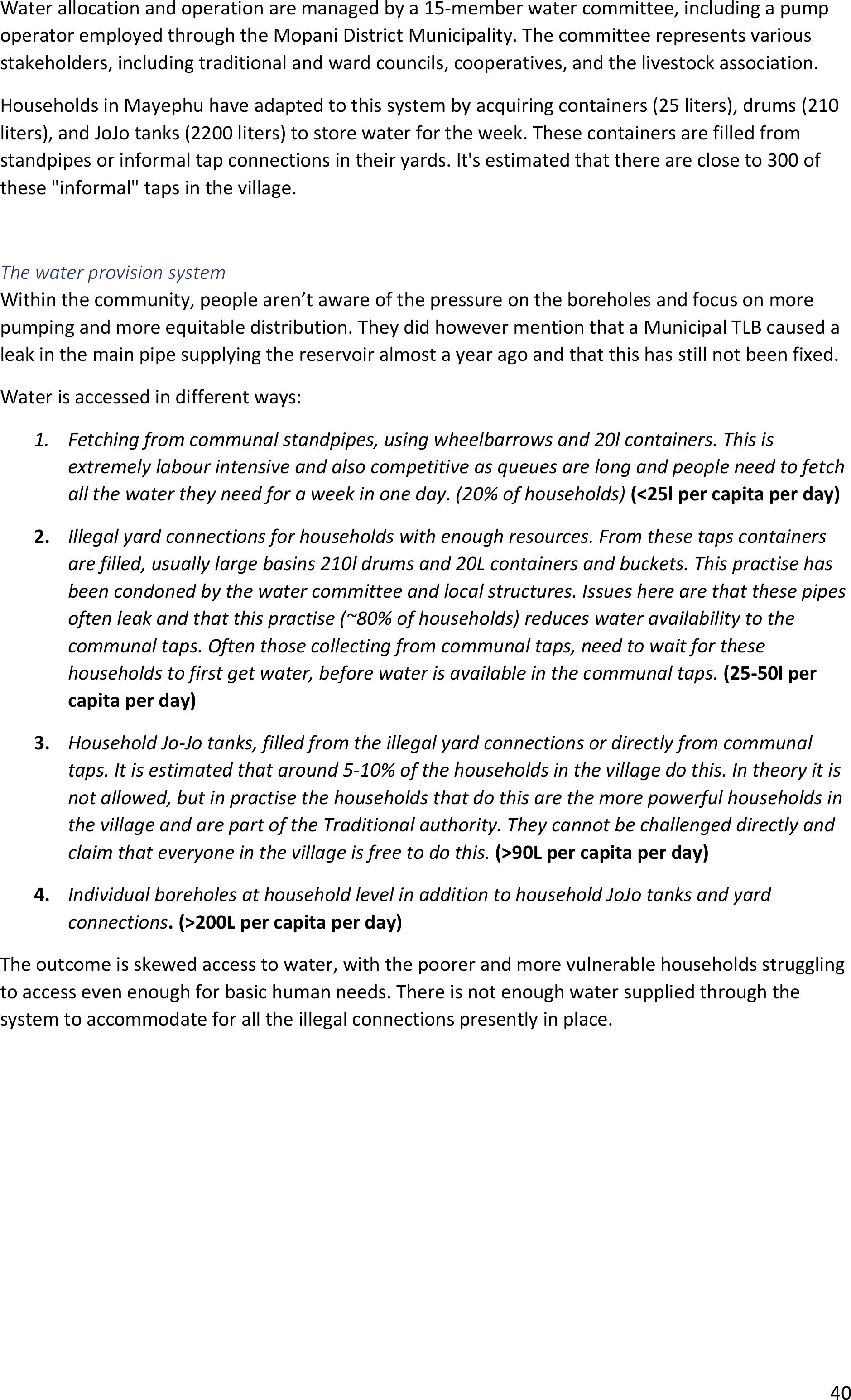

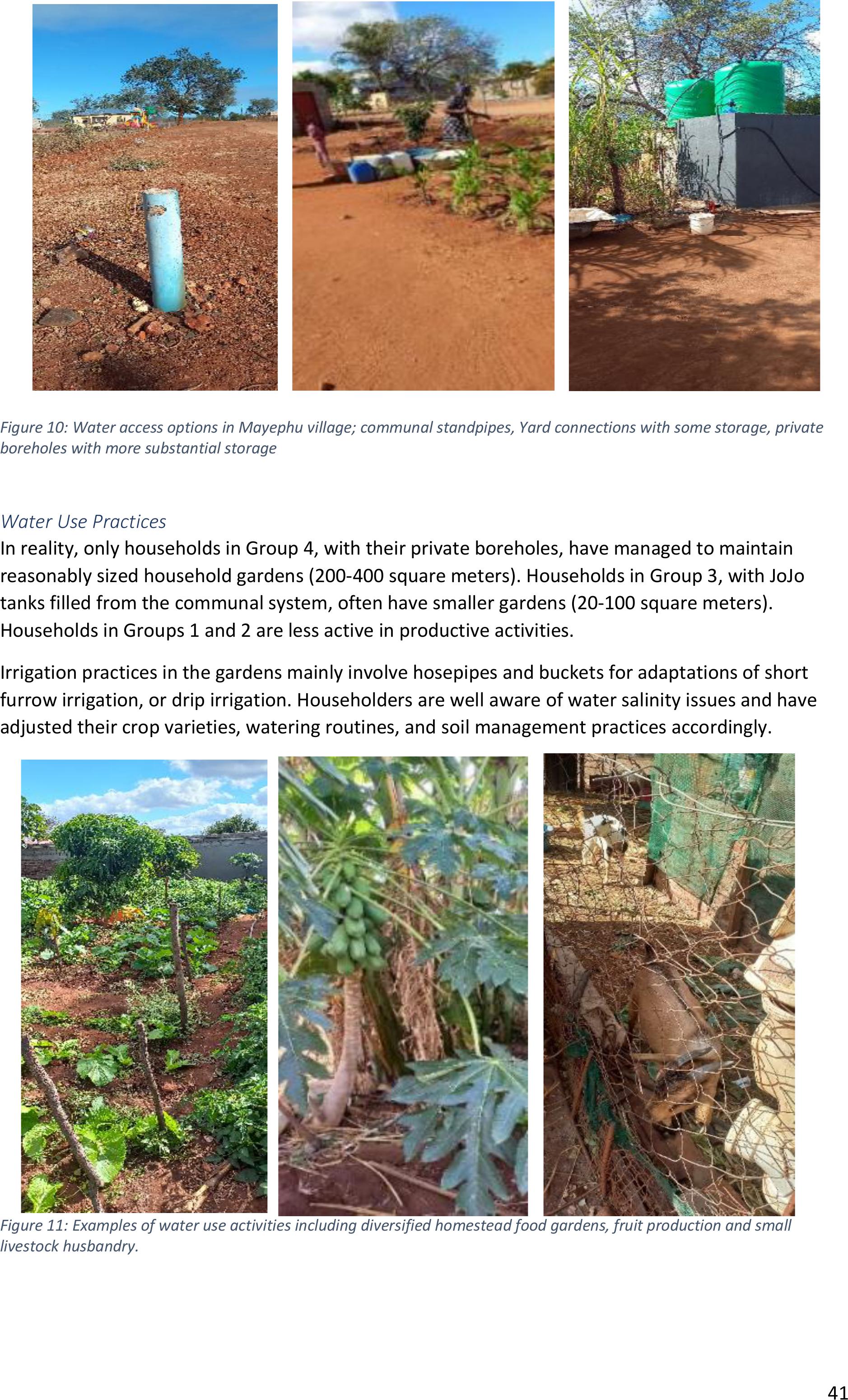

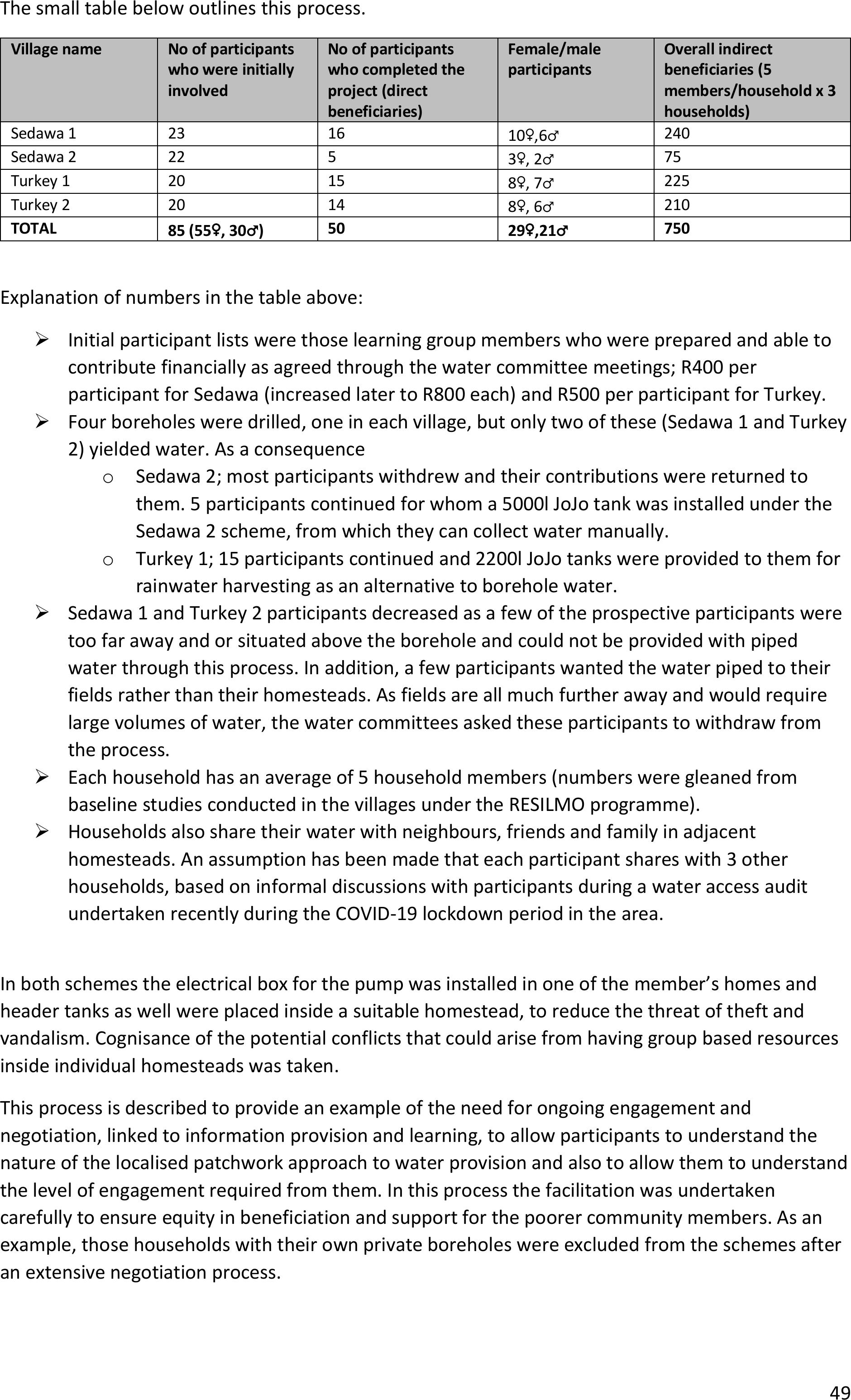

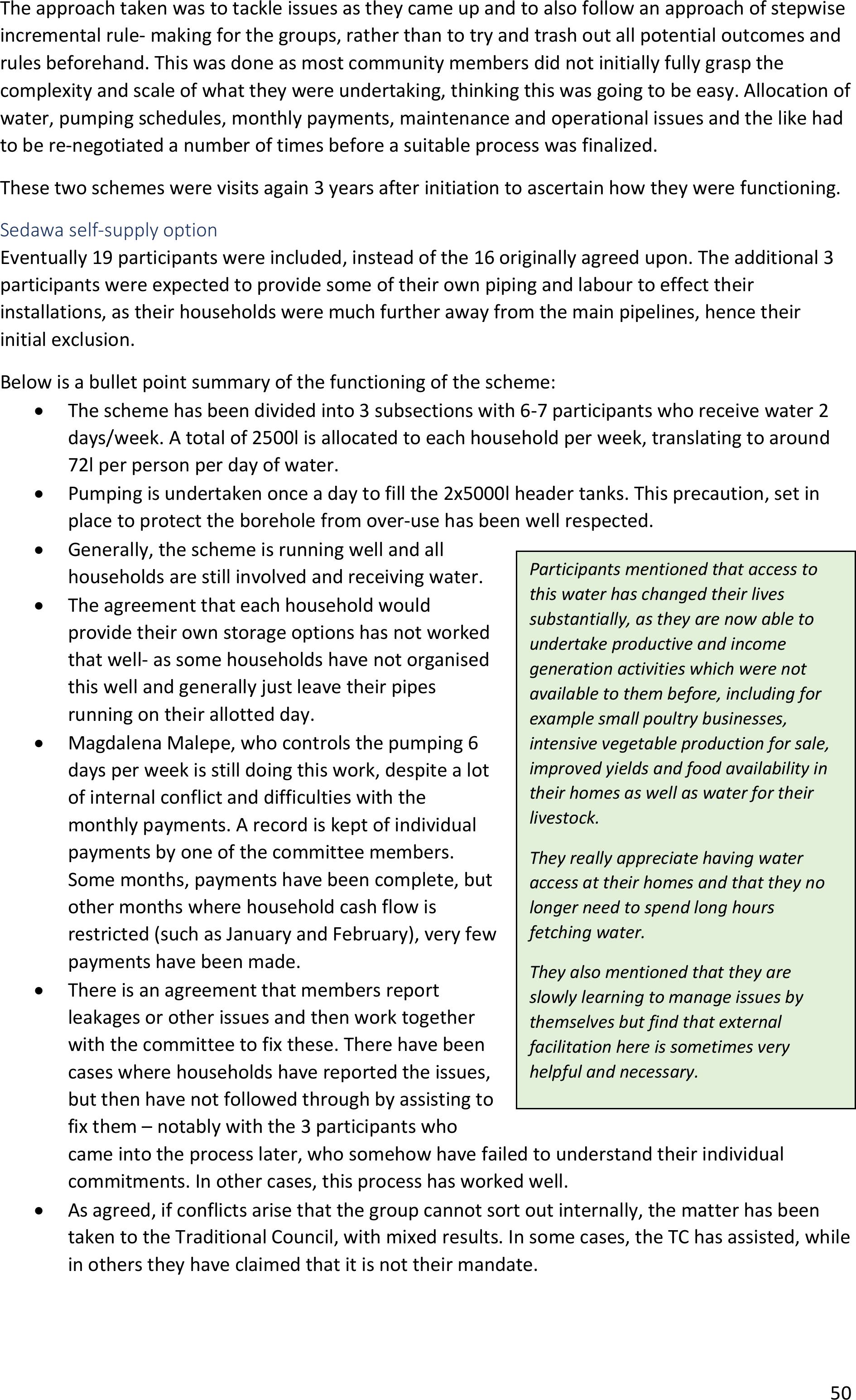

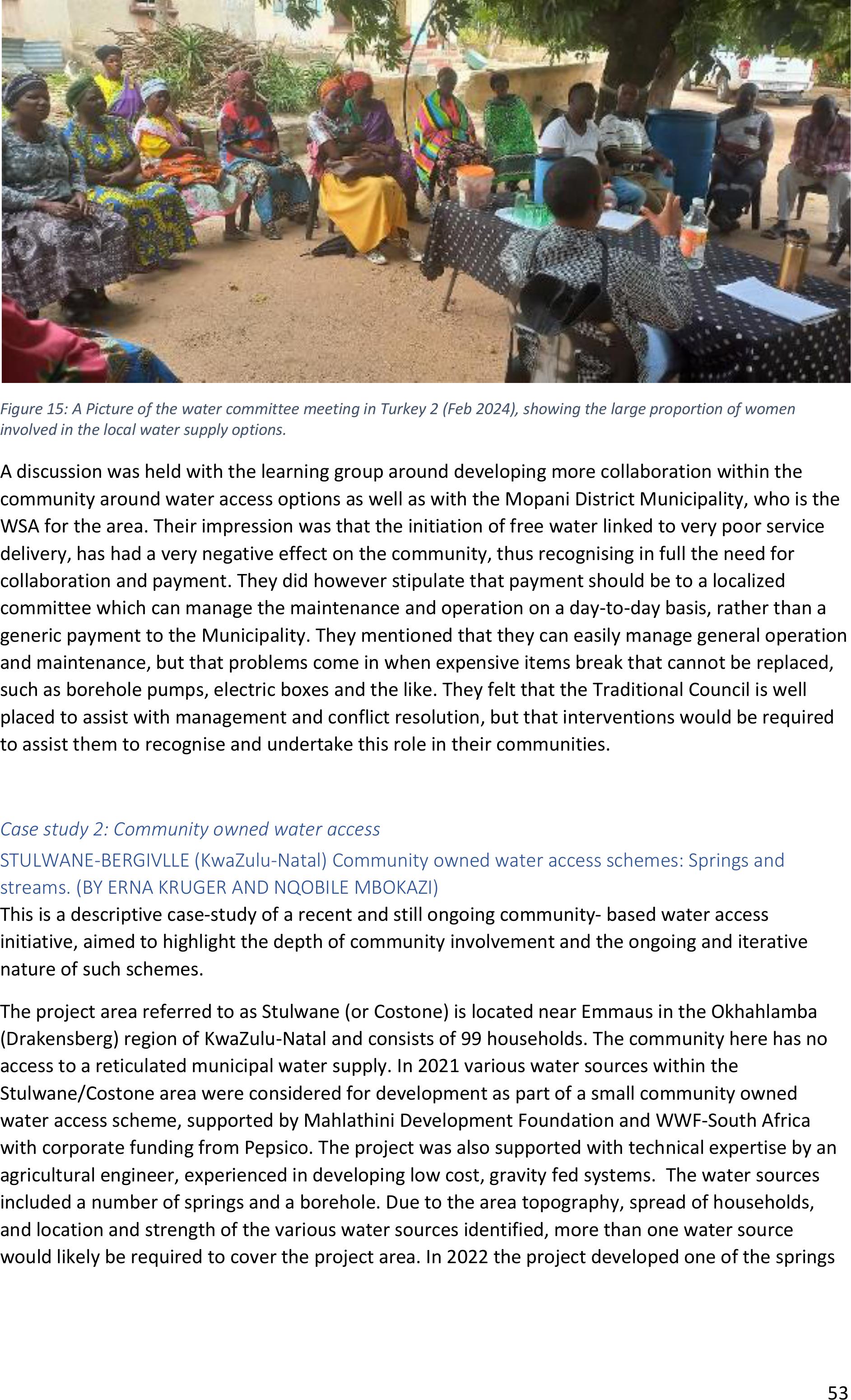

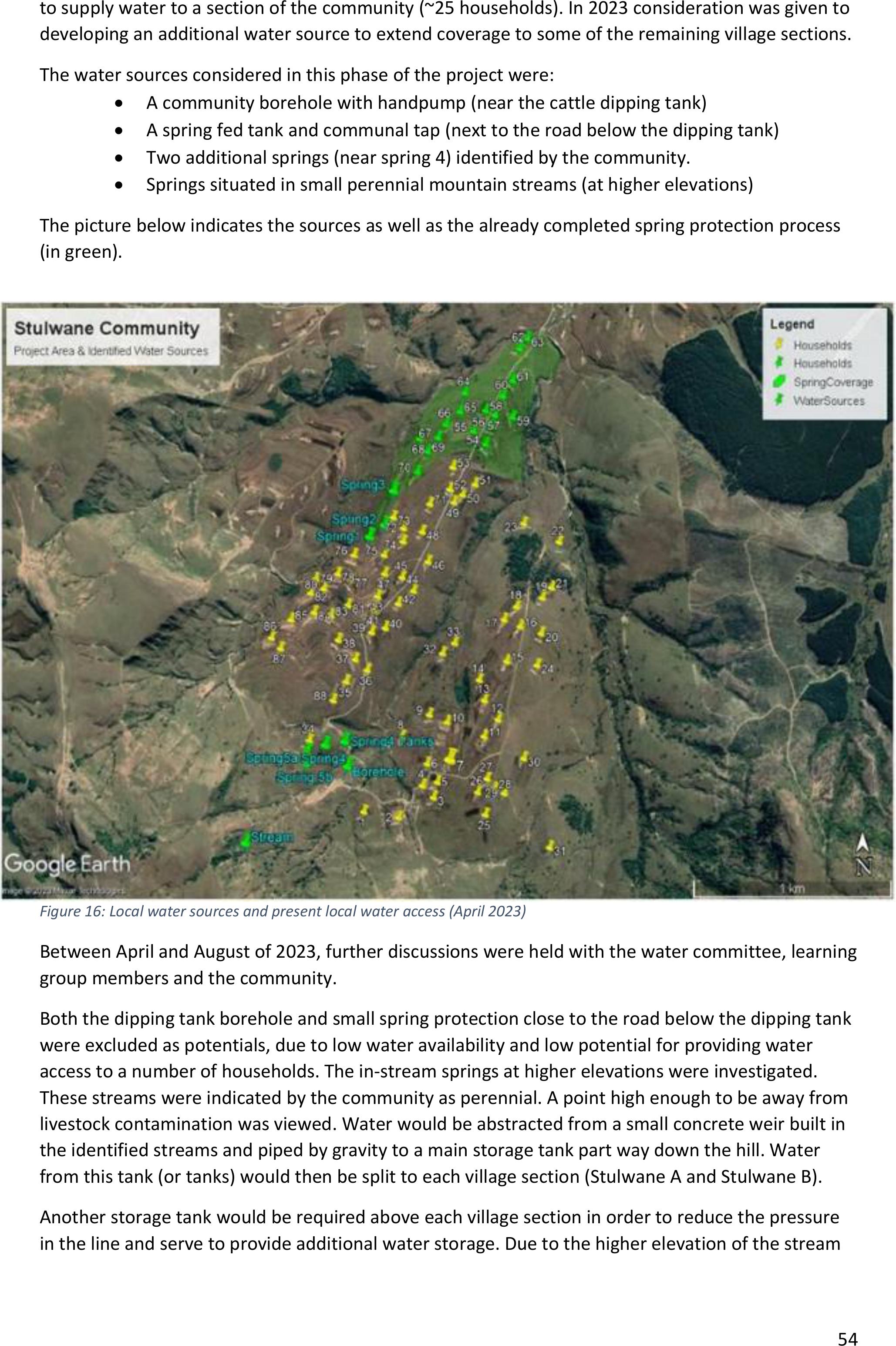

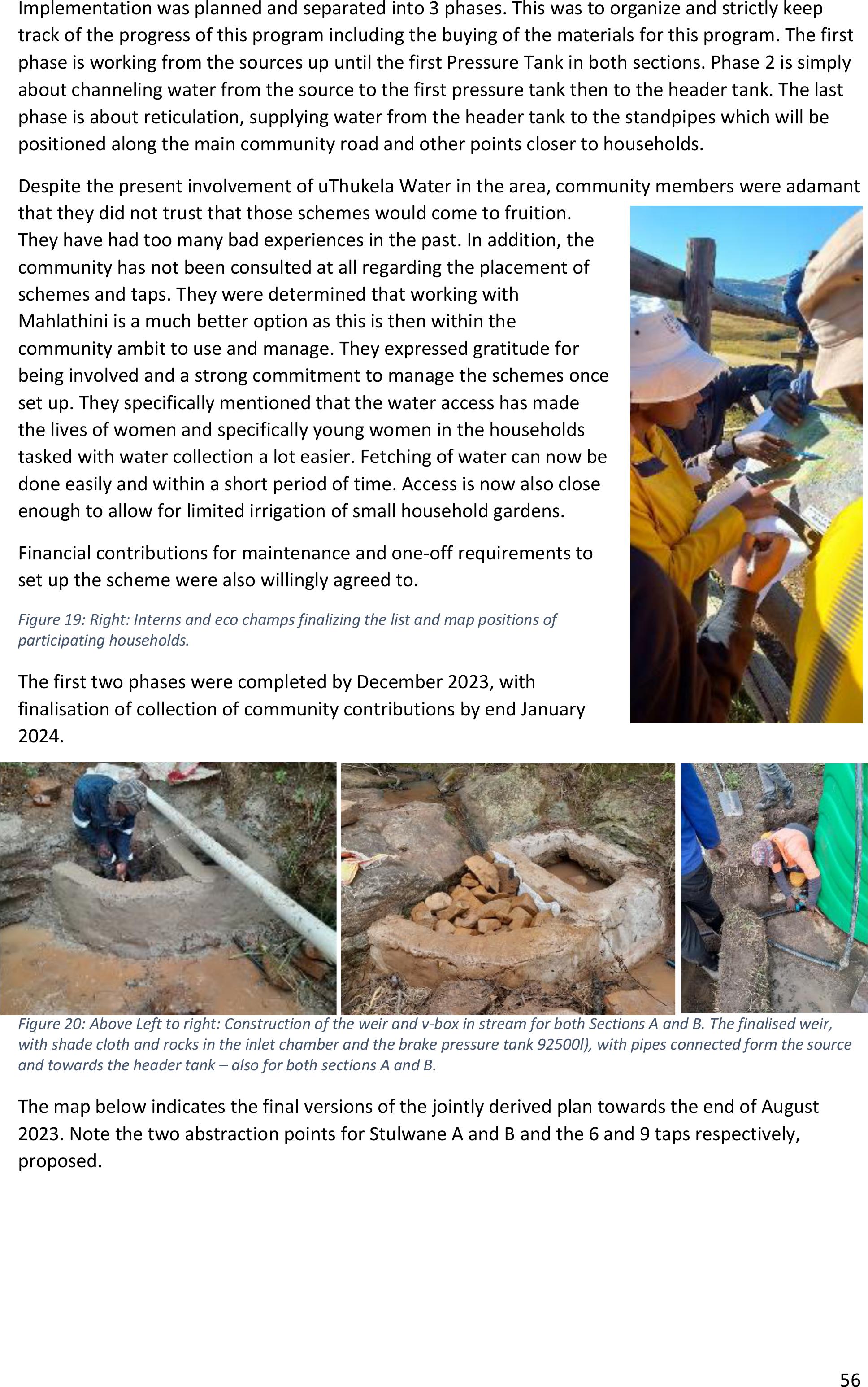

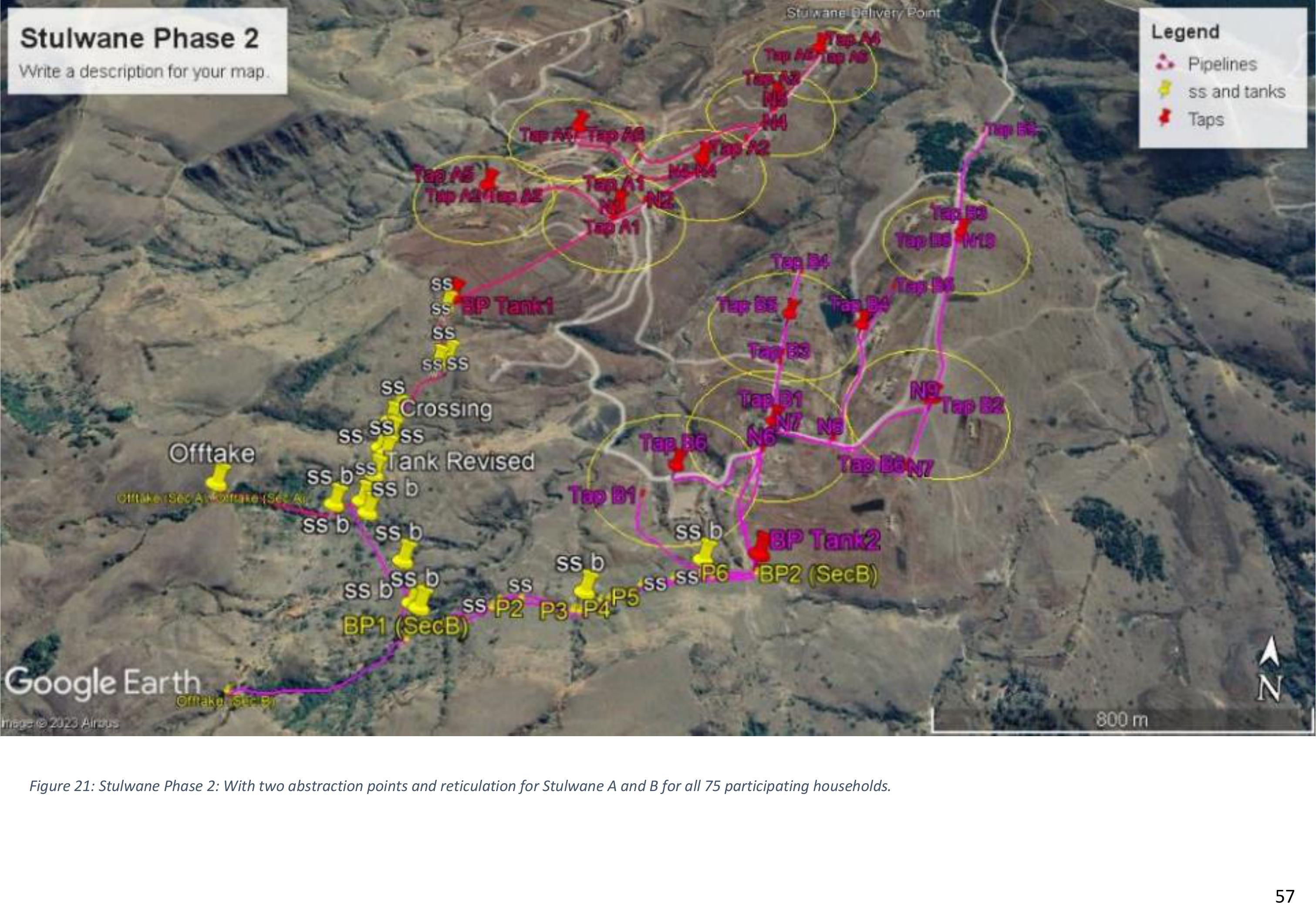

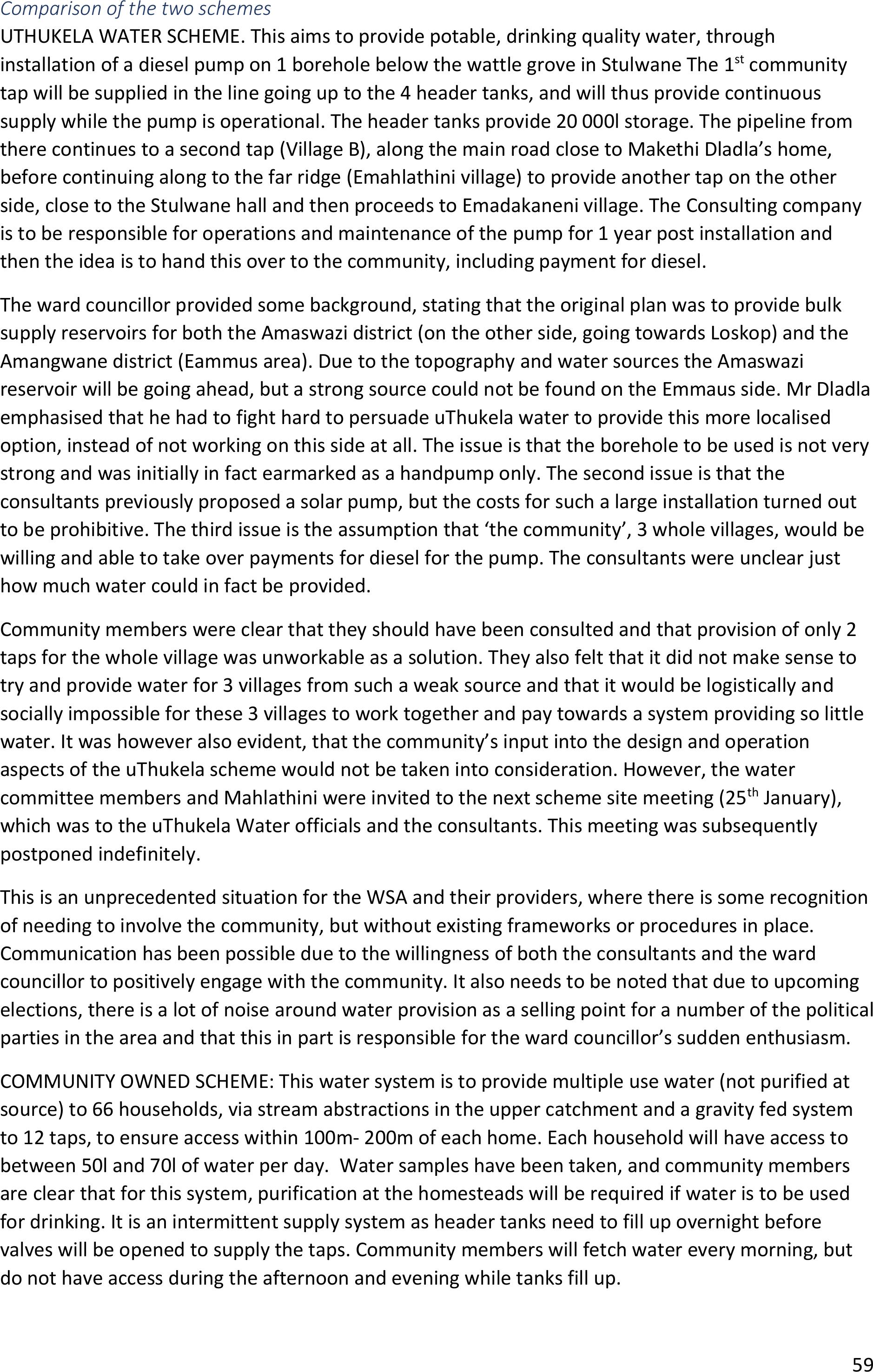

that these patrols can also undertake monitoring of the water infrastructure, within the same broad