Water Research Commission

Submitted to:

Dr Gerhard Backeberg

Executive Manager:Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Prepared By:

Project team led by Mahlathini Development Foundation.

Project Number: K5/2719/4

Project Title: Collaborative knowledge creation and mediation strategies for the dissemination of

Water and Soil Conservationpractices and Climate Smart Agriculture in smallholder farming

systems.

Deliverable No.4:Report- CoPs and Demonstration Sites Established

Date: May 2018

Deliverable

4

Submitted to:

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Project team:

Mahlathini Development Foundation

Erna Kruger

Sylvester Selala

Mazwi Dlamini

Khethiwe Mthethwa

Temakholo Mathebula

Institute of Natural Resources NPC

Jon McCosh

Rural Integrated Engineering (Pty) Ltd

Christiaan Stymie

Rhodes University Environmental Learning Research Centre

Lawrence Sisitka

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

3

CONTENTS

FIGURES 4

TABLES 4

1OVERVIEW OF PROJECT AND DELIVERABLE 5

Contract Summary 5

Project objectives5

Deliverables 5

Overview of Deliverable 4 6

2Cops and demonStration sites established 8

3CSA practices 8

Further practices suggested by local farmers 17

4Outcomes of CC dialogues (Workshop 1): Definitions, changes, present activities,

impacts 17

Overview 17

Impacts of CC on livelihoods and farming18

5Potential adaptive measures 19

6Continuation of CC dialogues (Workshop 2): Potential adaptive measures,

prioritisation of practices and experimentation planning22

Ezibomvini (KZN) CCAworkshop 2 25

Alice (Eastern Cape) CCA Workshop 29

7Baseline information 32

Household level questionnaires 32

Farmer typologies 35

Scale of operation42

Walkabouts 43

Tabamhlophe43

Ezibomvini 44

Case Study GrainSA SFIP: Conservation Agriculture builds a better life for Mrs Phumelele

Hlongwane (Bergville)45

Conservation Agriculture Experimentation47

Yield results47

Run-off results49

Mvuso (Alice) EC51

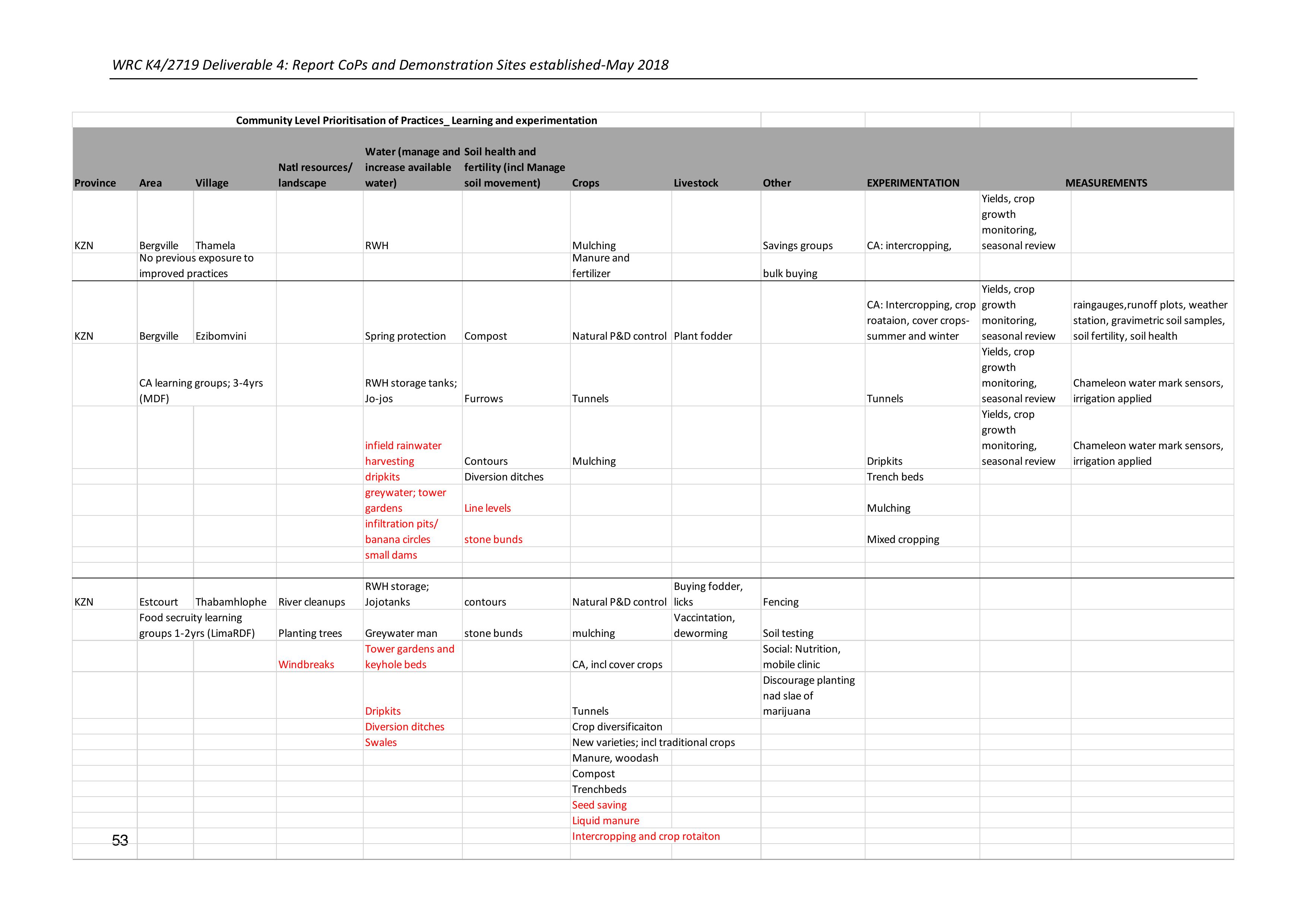

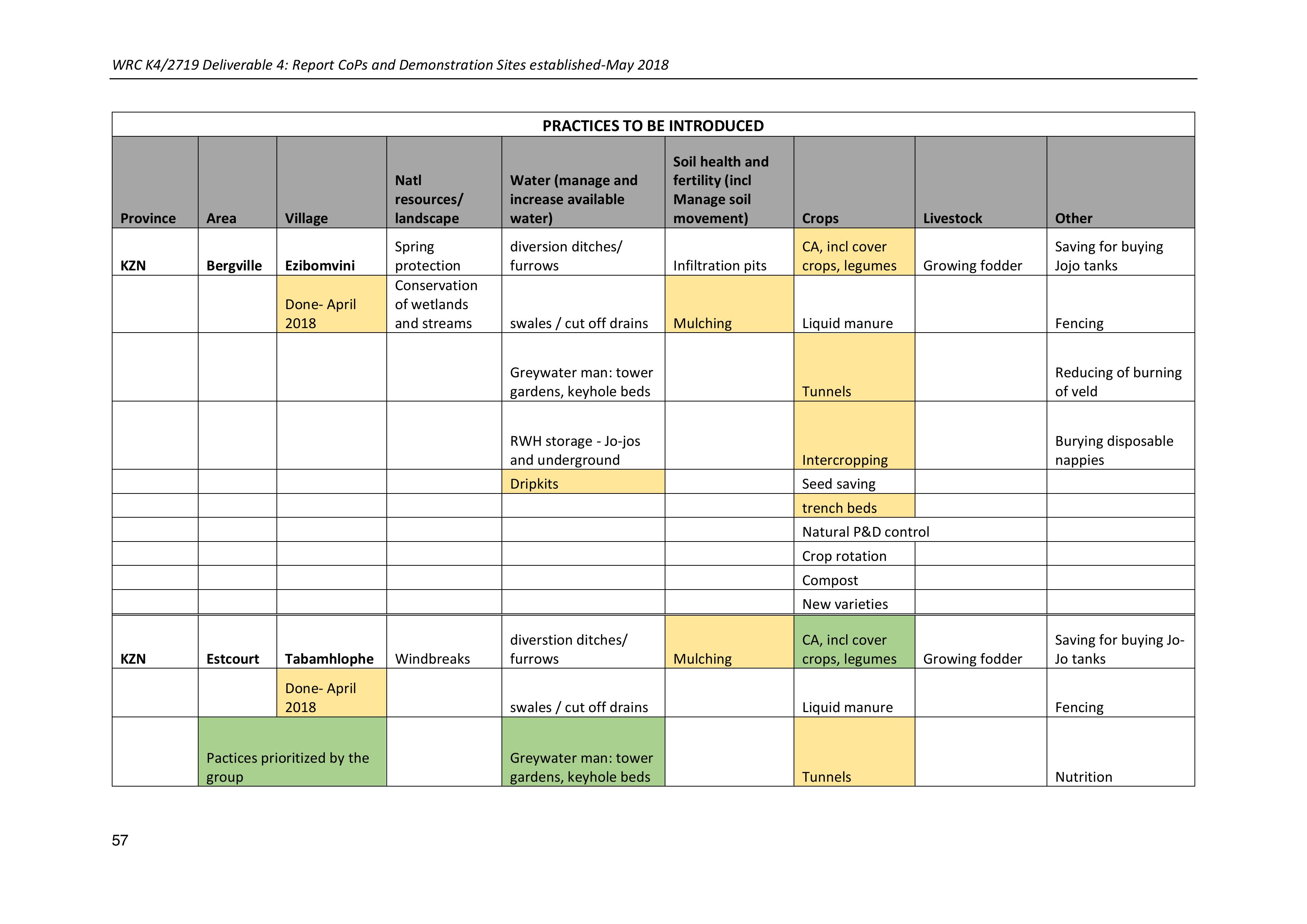

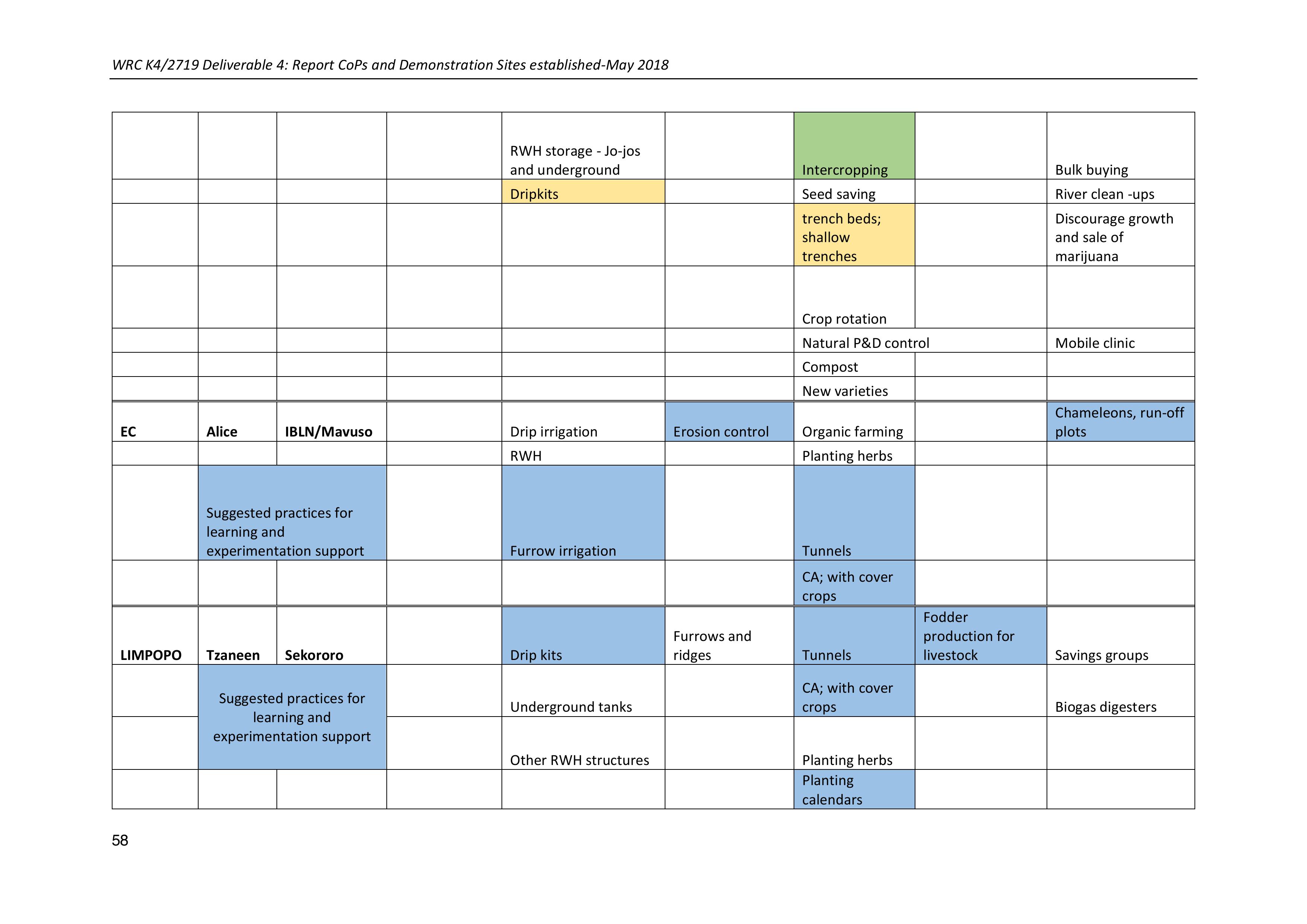

8Community level prioritization of Practices for Experimentation 52

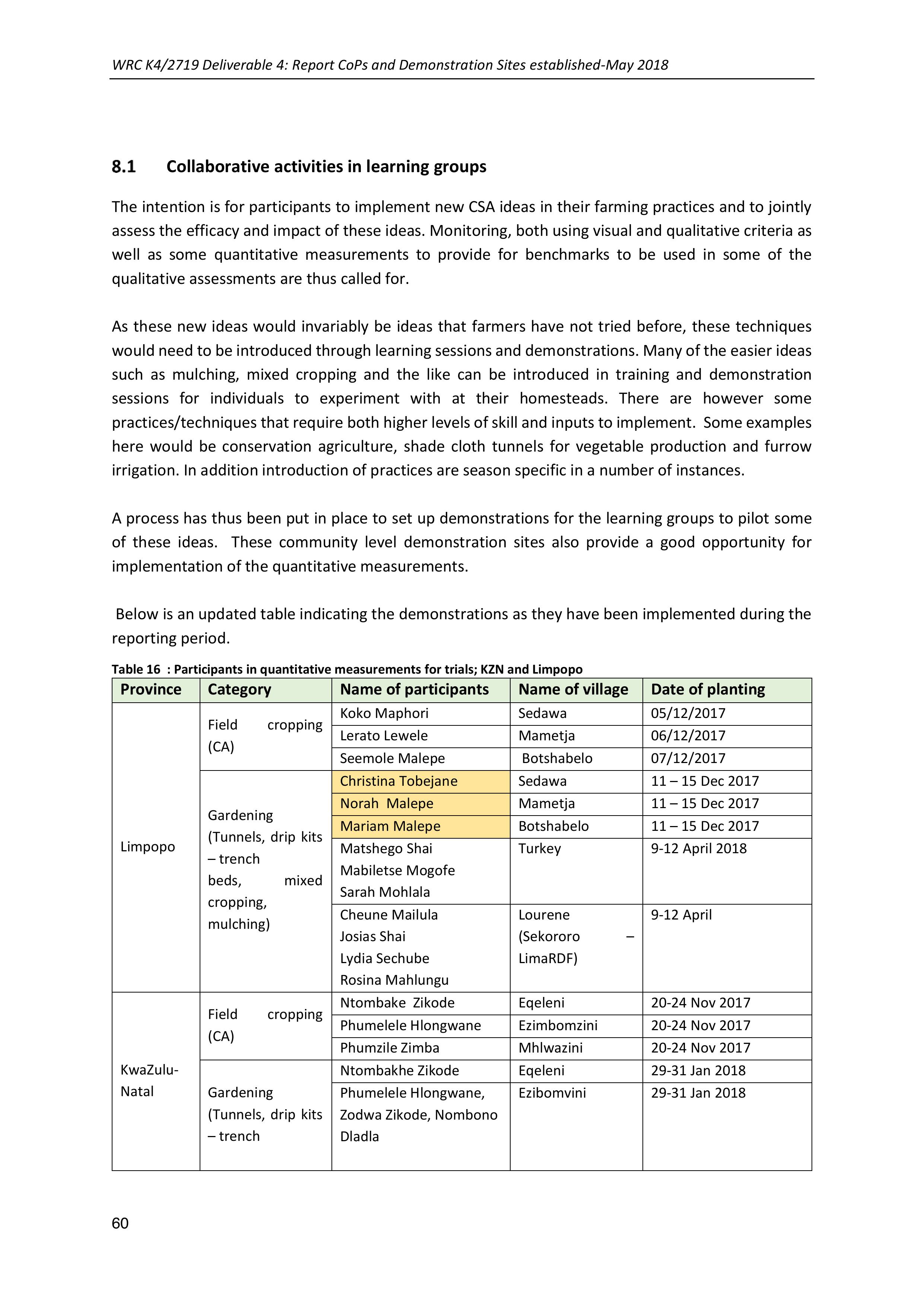

Collaborative activities in learning groups 60

Experimentation with vegetable production and tunnels61

Individual experimentation 62

Conservation Agriculture experimentation- Limpopo62

Tunnel and gardening experimentation _KZN- Ezibomvini 65

9Capacity building and publications67

Community level learning 67

Organisational capacity building 67

Post graduate students67

Sanelise Tafa:68

Khethiwe Mthethwa:70

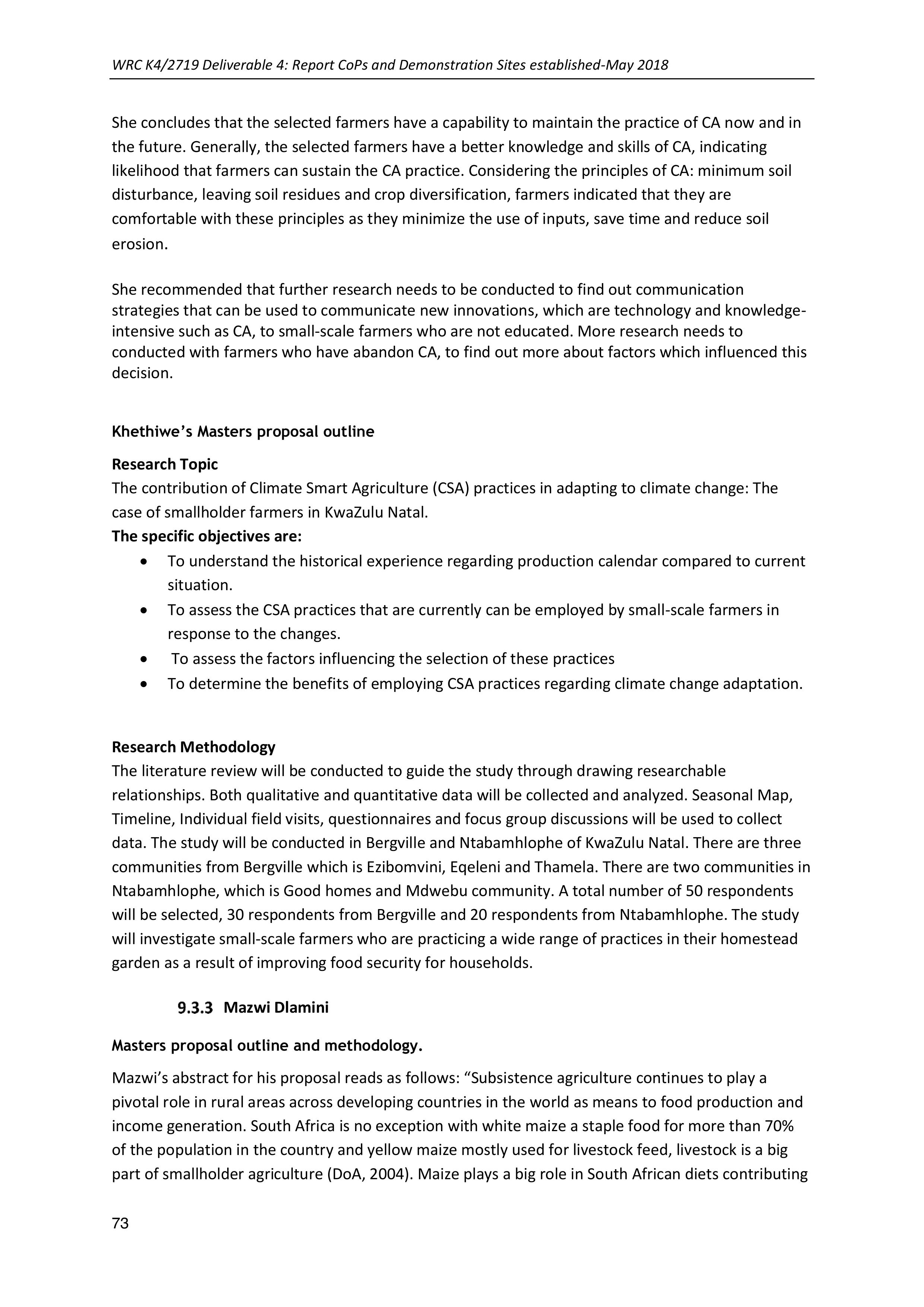

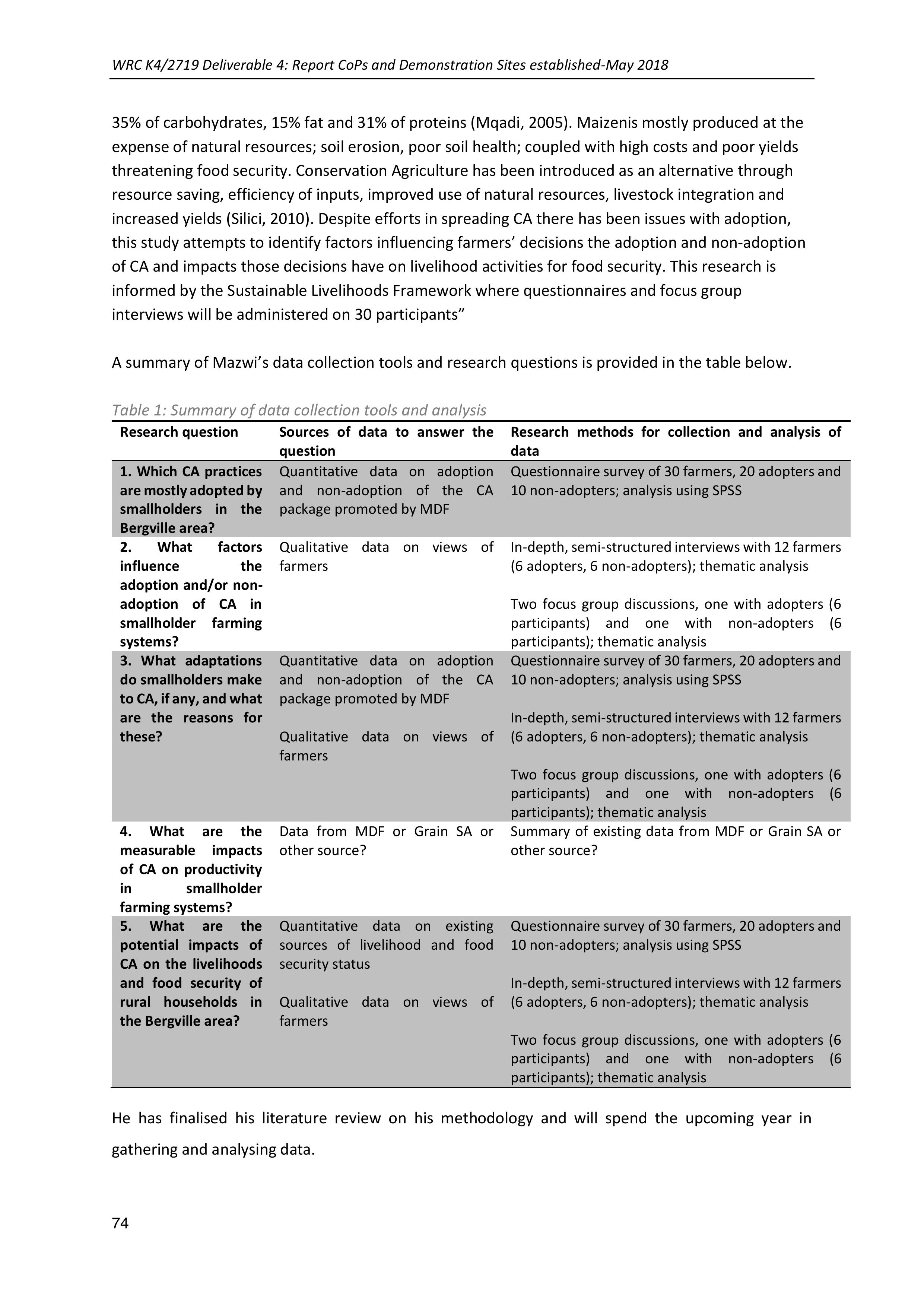

Mazwi Dlamini73

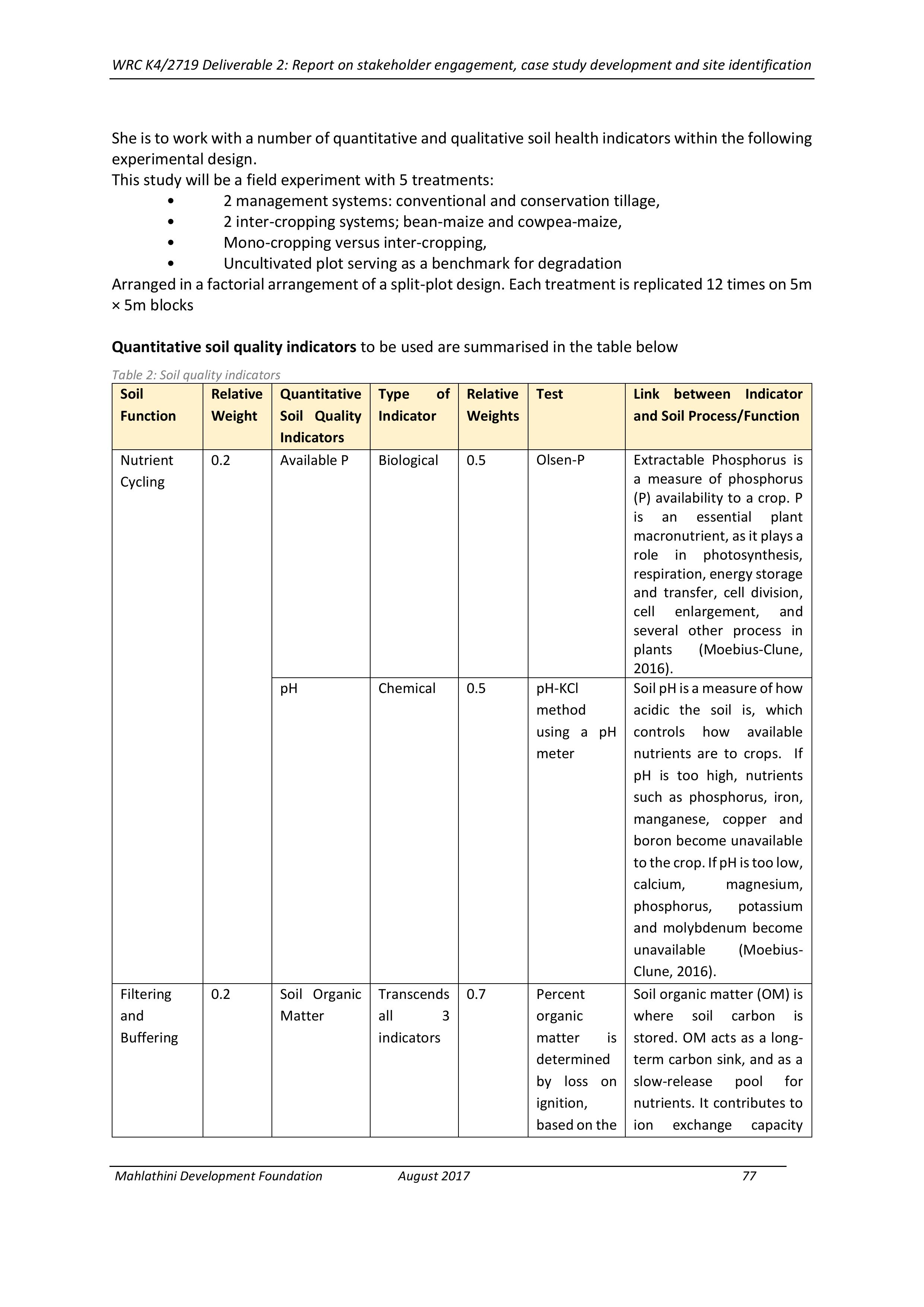

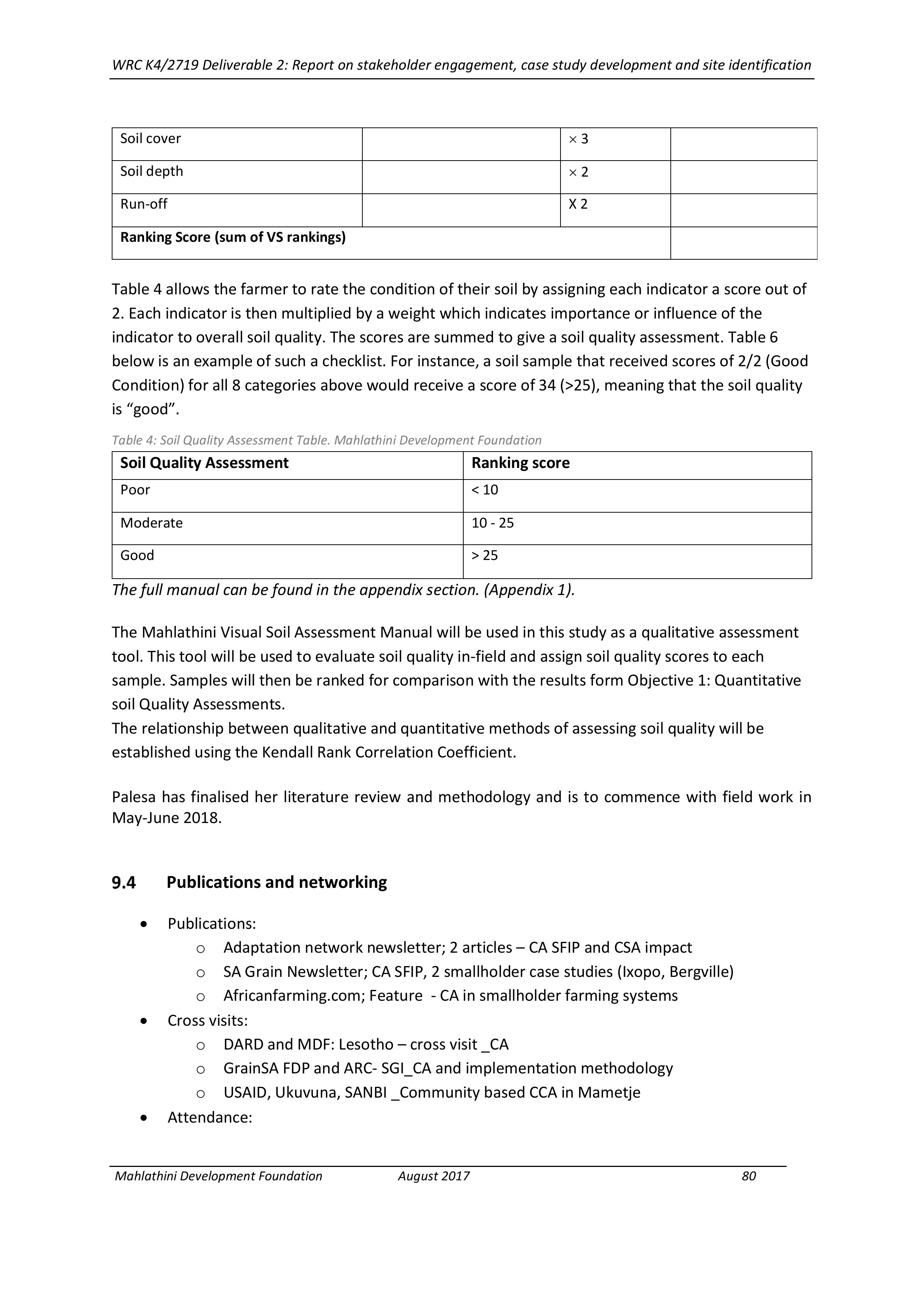

Palesa Motaung75

Publications and networking 80

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

4

FIGURES

Figure 1: The Smallholder decision support system process ................................................................32

Figure 2:Baseline information for CCA workshop participants .............................................................34

Figure 3: Household, scale of farming and income information for CCA participants .........................35

Figure 4: CAtrial layout for Koko Maphori’s field (Plots highlighted in brown is where runoff plots have

been installed) ......................................................................................................................................65

TABLES

Table 1: Deliverables for the research period; completed .....................................................................5

Table 2: CoPs’ established in three provinces........................................................................................8

Table 3: Summary of climate change impacts from community level workshops ...............................18

Table 4: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Turkey (Limpopo) climate change

dialogue process ...................................................................................................................................19

Table 5: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Thamela (KZN)) climate change dialogue

process ..................................................................................................................................................20

Table 6: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Sekororo (Limpopo) climate change

dialogue process ...................................................................................................................................21

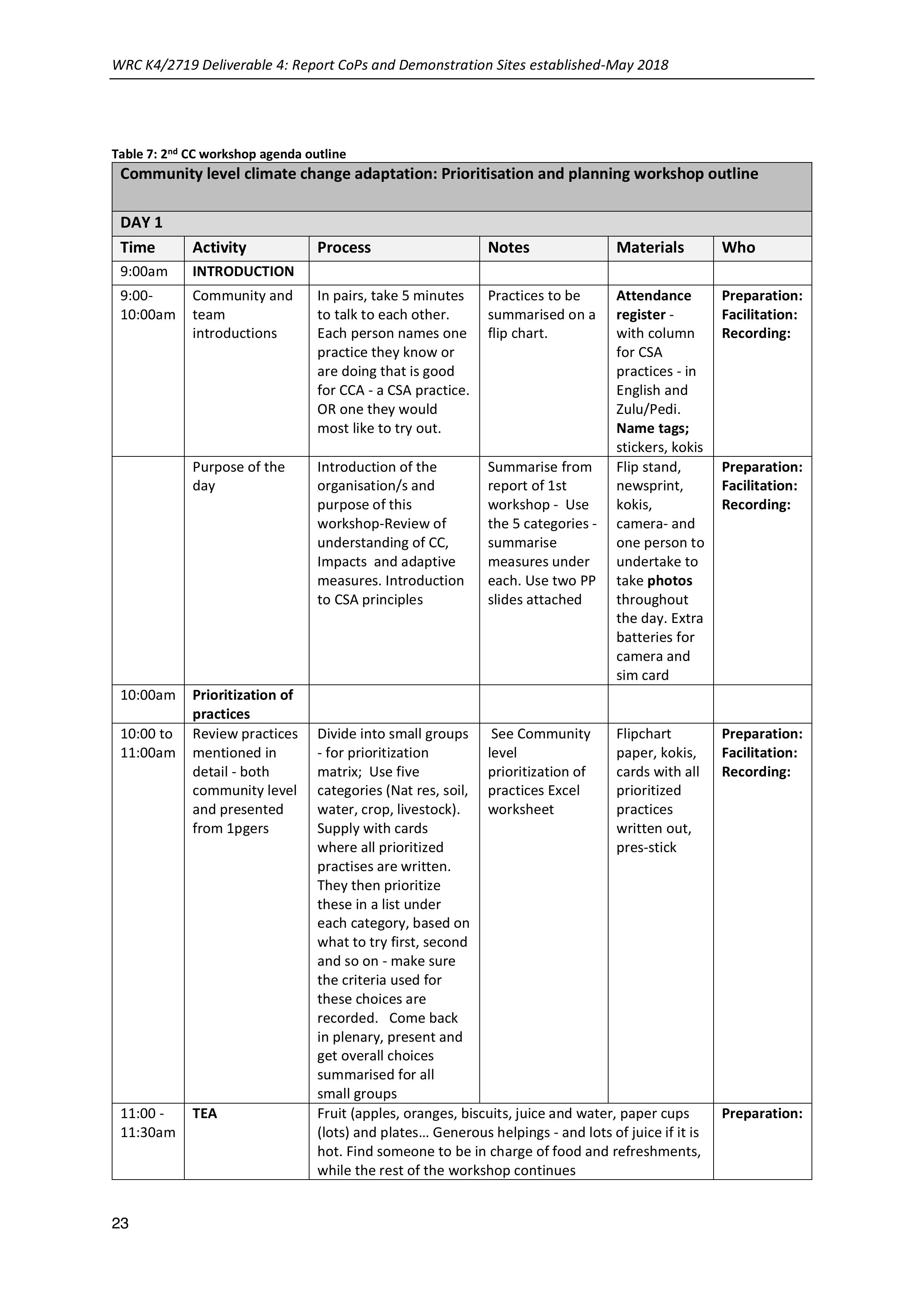

Table 7: 2nd CC workshop agenda outline .............................................................................................23

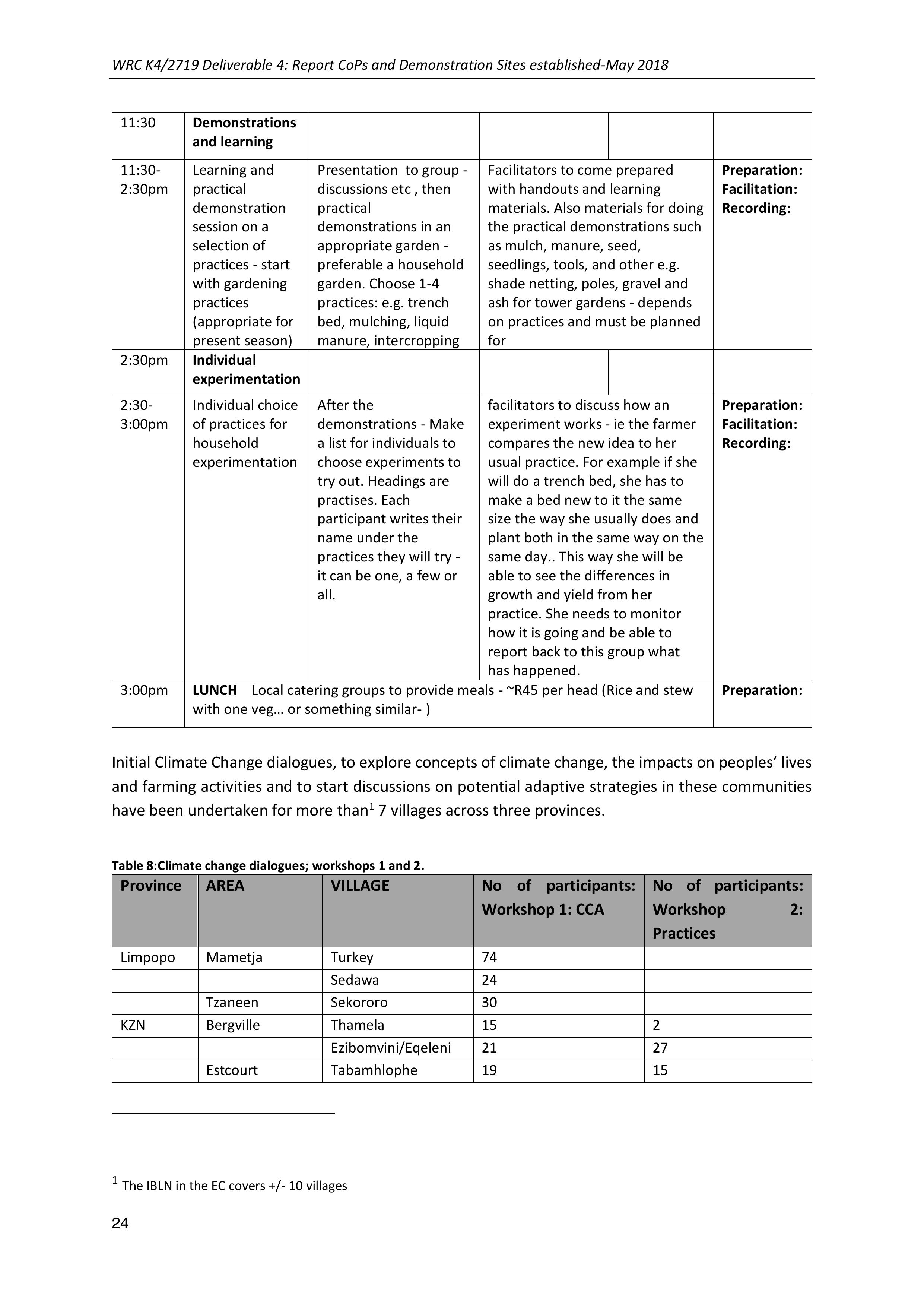

Table 8:Climate change dialogues; workshops 1 and 2. .......................................................................24

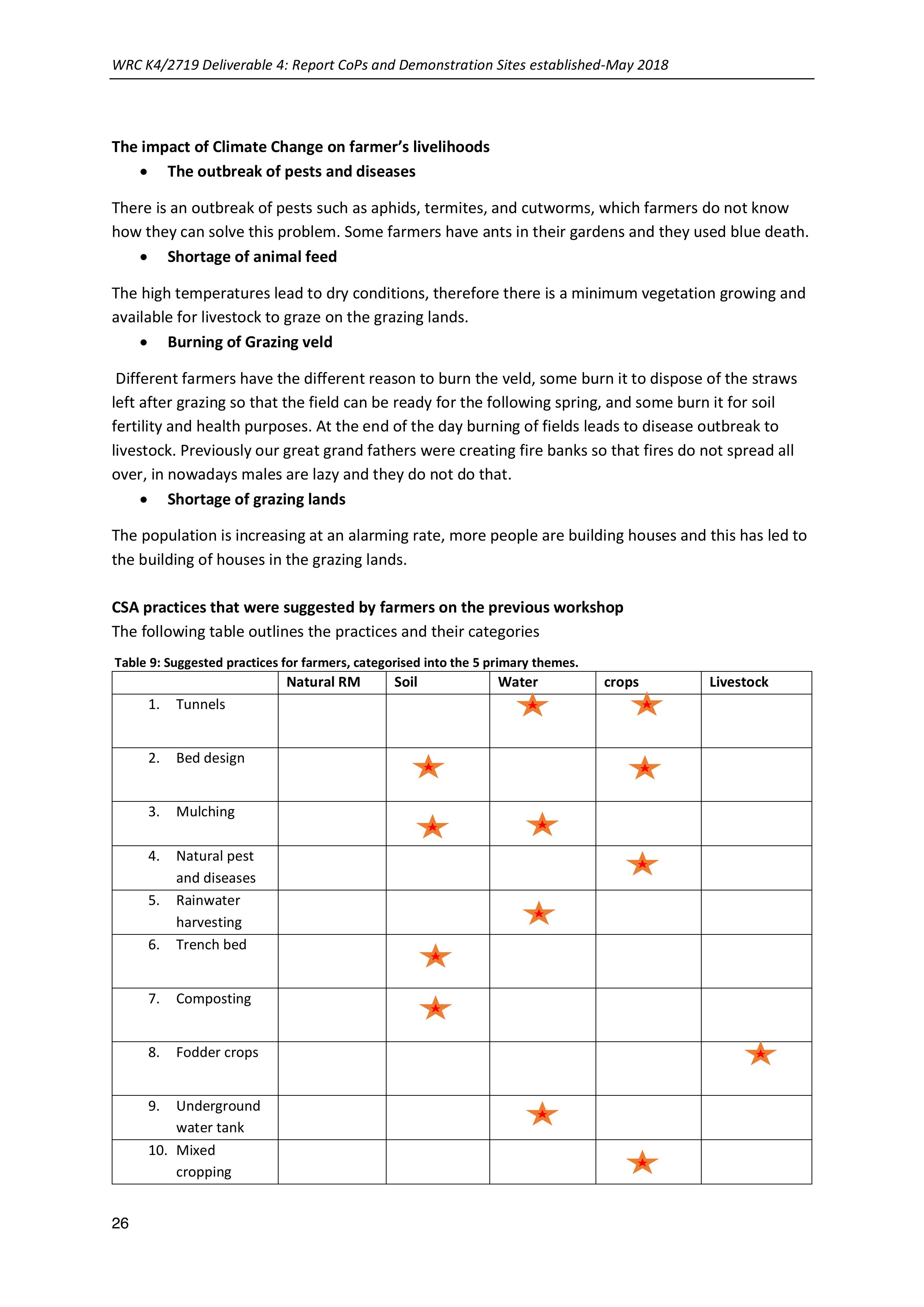

Table 9: Suggested practices for farmers, categorised into the 5 primary themes..............................26

Table 10: Individual volunteers for trench bed experimentation in KZN (Bergville) ............................28

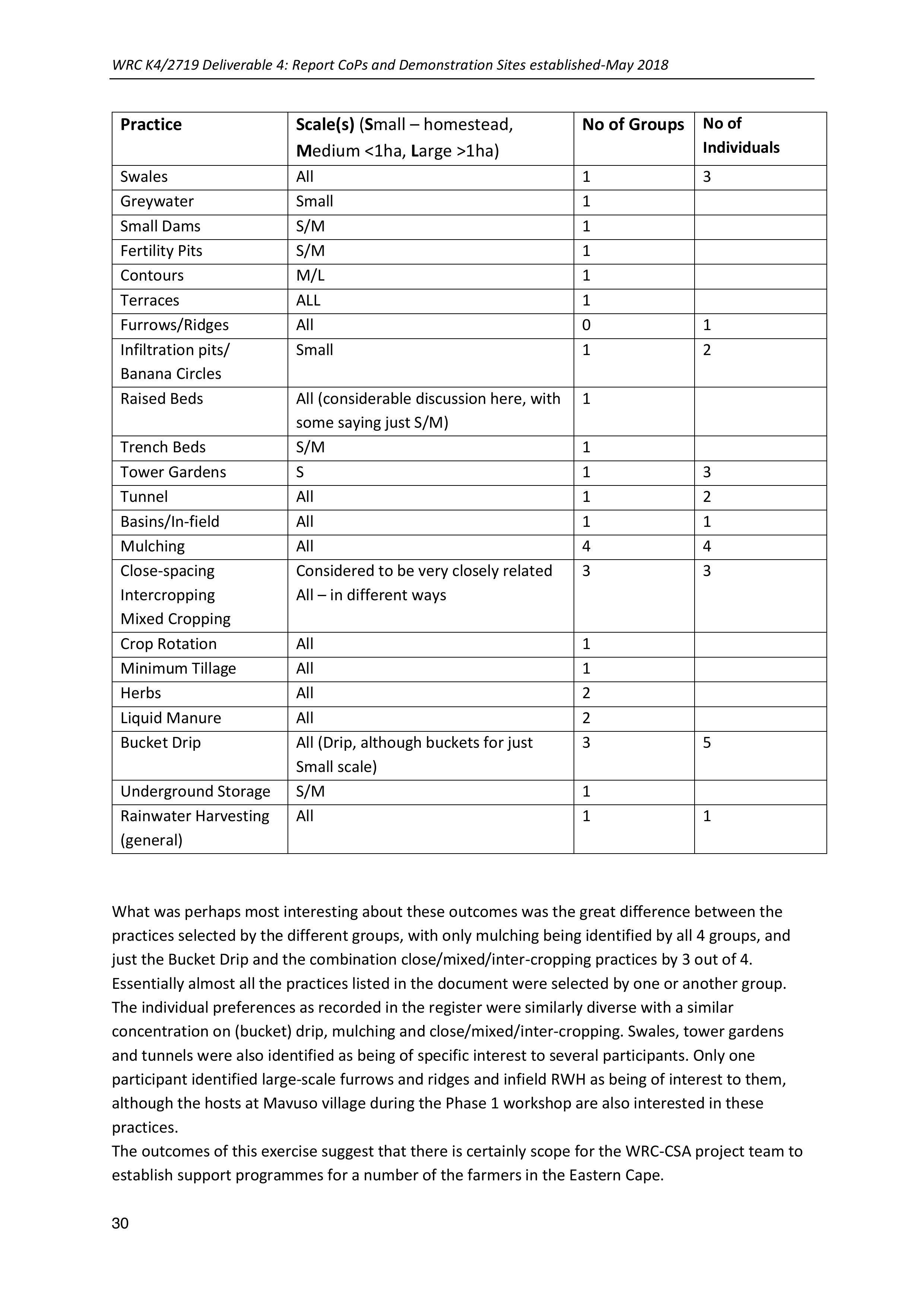

Table 11:CSA Practices: Prioritization by groups and individuals .........................................................29

Table 12: Farmer segmentation in the Bergville smallholder farming system .....................................36

Table 13: Baseline information related to incomes ..............................................................................37

Table 14: Farmer typology for the WRC-CCA process ..........................................................................40

Table 15:Summary of scale of operation for present participants in the WRC-CCA process ...............42

Table 16 : Participants in quantitative measurements for trials; KZN and Limpopo ...........................60

Table 17: Participants in the individual CA farmer experimentation in Limpopo ...............................62

Table 18: Individual experimentation with trench beds, mixed cropping and mulching for the

Ezibomvini Learning Group ...................................................................................................................65

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

5

Report-CoPsanddemonstrationsites

established

1OVERVIEW OF PROJECT AND DELIVERABLE

Contract Summary

Project objectives

1.To evaluate and identify best practice options for CSA and Soil and Water Conservation

(SWC) in smallholder farming systems, in two bioclimatic regions in South Africa. (Output 1)

2.To amplify collaborative knowledge creation of CSA practices with smallholder farmers in

South Africa (Output 2)

3.To test and adapt existing CSA decision support systems (DSS) for the South African smallholder

context (Outputs 2,3)

4.To evaluate the impact of CSA interventions identified through the DSS by piloting interventions

in smallholder farmer systems, considering water productivity, social acceptability and farm-scale

resilience (Outputs 3,4)

5.Visual and proxy indicators appropriate for a Paymentfor Ecosystems based model aretested at

community level for local assessment of progress and tested against field and laboratory analysis

of soil physical and chemical properties, and water productivity (Output 5)

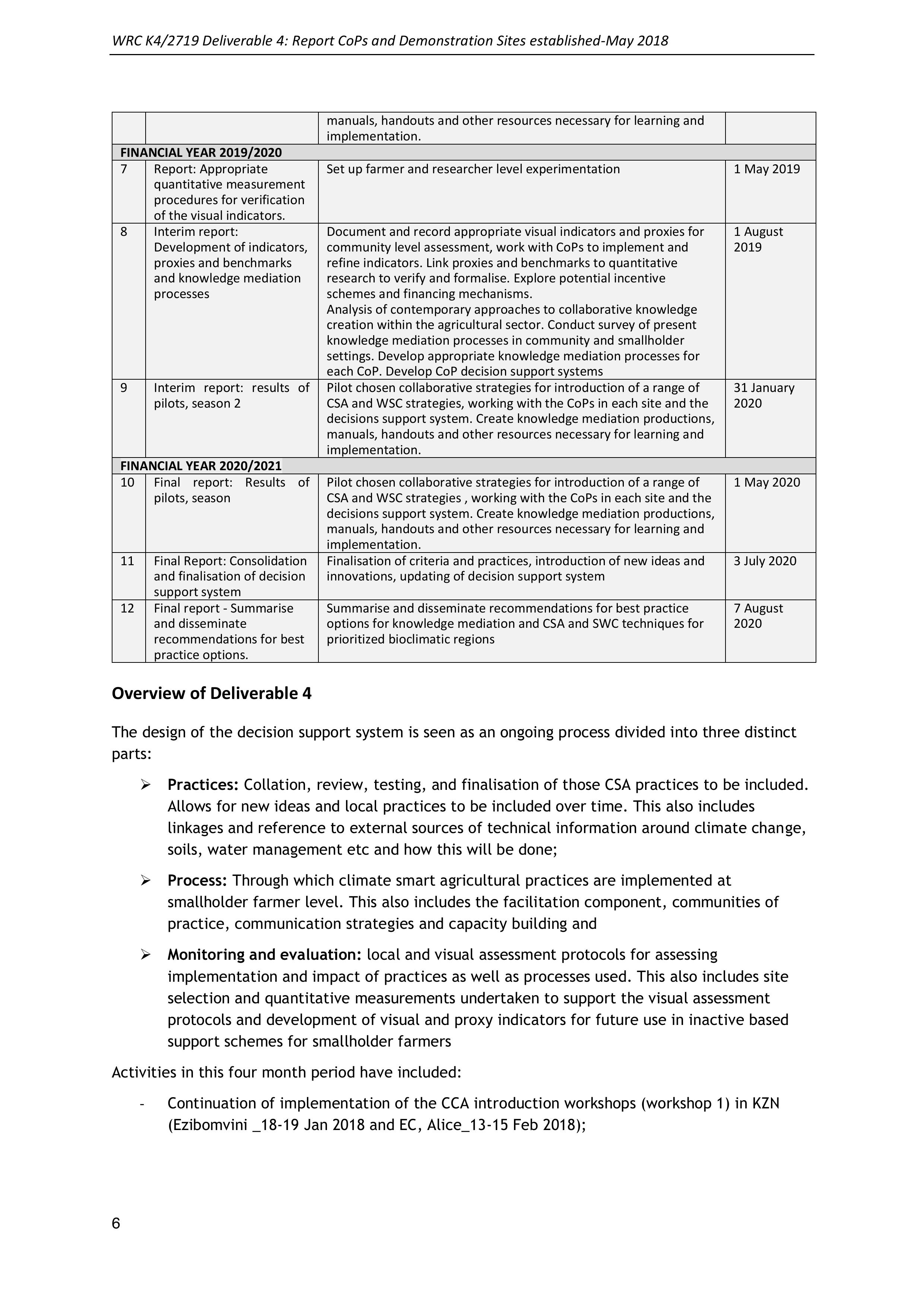

Deliverables

Table 1: Deliverables for the research period; completed

No

Deliverable

Description

Target date

FINANCIAL YEAR 2017/2018

1

Report: Desktop review of

CSA and WSC

Desktop review of current science, indigenous and traditional

knowledge, and best practice in relation to CSA and WSC in the

South African context

1 June 2017

2

Report on stakeholder

engagement and case

study development and

site identification

Identifying and engaging with projects and stakeholders

implementing CSA and WSC processes and capturing case studies

applicable to prioritized bioclimatic regions

Identification of pilot research sites

1 September

2017

3

Decision support system

for CSA in smallholder

farming developed

(Report)

Decision support system for prioritization of best bet CSA options in

a particular locality; initial database and models. Review existing

models, in conjunction with stakeholder discussions for initial

criteria

15 January

2018

FINANCIAL YEAR: 2018/2019

4

CoPs and demonstration

sites established (report)

Establish communities of practice (CoP)s including stakeholders and

smallholder farmers in each bioclimatic region.5. With each CoP,

identify and select demonstration sites in each bioclimatic region

and pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range

of CSA and WSC strategies in homestead farming systems (gardens

and fields)

1 May 2018

5

Interim report: Refined

decision support system

for CSA in smallholder

farming (report)

Refinement of criteria and practices, introduction of new ideas and

innovations, updating of decision support system

1 October

2018

6

Interim report: Results of

pilots, season 1

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies, working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

31 January

2019

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

6

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/2020

7

Report: Appropriate

quantitative measurement

procedures for verification

of the visual indicators.

Set up farmer and researcher level experimentation

1 May 2019

8

Interim report:

Development of indicators,

proxies and benchmarks

and knowledge mediation

processes

Document and record appropriate visual indicators and proxies for

community level assessment, work with CoPs to implement and

refine indicators. Link proxies and benchmarks to quantitative

research to verify and formalise. Explore potential incentive

schemes and financing mechanisms.

Analysis of contemporary approaches to collaborative knowledge

creation within the agricultural sector. Conduct survey of present

knowledge mediation processes in community and smallholder

settings. Develop appropriate knowledge mediation processes for

each CoP. Develop CoP decision support systems

1 August

2019

9

Interim report: results of

pilots, season 2

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies, working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

31 January

2020

FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021

10

Final report: Results of

pilots, season

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies , working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

1 May 2020

11

Final Report: Consolidation

and finalisation of decision

support system

Finalisation of criteria and practices, introduction of new ideas and

innovations, updating of decision support system

3 July 2020

12

Final report - Summarise

and disseminate

recommendations for best

practice options.

Summarise and disseminate recommendations for best practice

options for knowledge mediation and CSA and SWC techniques for

prioritized bioclimatic regions

7 August

2020

Overview of Deliverable 4

The design of the decision support system is seen as an ongoing process divided into three distinct

parts:

➢Practices: Collation, review, testing, and finalisation of those CSA practices to be included.

Allows for new ideas and local practices to be included over time. This also includes

linkages and reference to external sources of technical information around climate change,

soils, water management etc and how this will be done;

➢Process: Through which climate smart agricultural practices are implemented at

smallholder farmer level. This also includes the facilitation component, communities of

practice, communication strategies and capacity building and

➢Monitoring and evaluation: local and visual assessment protocols for assessing

implementation and impact of practices as well as processes used. This also includes site

selection and quantitative measurements undertaken to support the visual assessment

protocols and development of visual and proxy indicators for future use in inactive based

support schemes for smallholder farmers

Activities in this four month period have included:

-Continuation of implementation of the CCA introduction workshops (workshop 1) in KZN

(Ezibomvini _18-19 Jan 2018 and EC, Alice_13-15 Feb 2018);

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

7

-Initiation of collaborative activities in 6 villages (KZN and Limpopo): Tunnels and drip kits

(Thabamhlophe, Ezibomvini, Eqeleni_29-31 Jan 2018 Sedawa, Lourene, Turkey_9-12 April

2018); CSA gardening practices (Turkey_ Jan, March 2018)

-Team planning meeting; including training of trainers (16 March 2018)_ Outline and

planning for CCA workshop 2 (Prioritization of practices)

-Implementation of CCA Workshop 2 in 3 villages (KZN and EC): Ezibomvini (22,23 March

2018), Thabamhlophe (17-18 April 2018), Alice (16-17 April 2018).

-Dialogues in climate change adaptation- including prioritization of practices – Limpopo (13-

15 March 2018)

-Visual and descriptive outlines of all practices in the database; Attached as a separate

document

-Set up of sites for quantitative measurements: KZN – field sites (Ezibomvini, Eqeleni,

Mhlwazini); garden site (Ezibomvini), Limpopo – field sites (Sedawa, Mametje, Botshabelo)

garden site (Sedawa); weather stations, run-off plots, gravimetric water sampling, soil

health sampling, soil fertility sampling, chameleon water sensors.

-Capacity building and publications:

oResearch presentations and chapters:

▪Khethiwe Mthethwa – Agric Honours( UKZN -Completed cum

laude);Investigating the sustainability of adoption of conservation

agriculture by small-scale farmers in Bergville, Dec 2017),

▪Mazwi Dlamini – M Phil (PLAAS UWC-yr 2); completed proposal and research

methodology

▪Palesa Motaung- M Agric (UP- yr 2); completed proposal and research

methodology

oNewsletter articles: Adaptation Network newsletter, SA Grain Newsletter, African

Farming.Com - Feature

oRangeland learning exchange visit (UCPP_6-8 Feb 2018), Regenerative Agriculture

oConference-Reitz (GrainSA and Landbouweekblad_19-20 March 2018).

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

8

2COPS AND DEMONSTRATION SITES ESTABLISHED

Table 2: CoPs’ established in three provinces

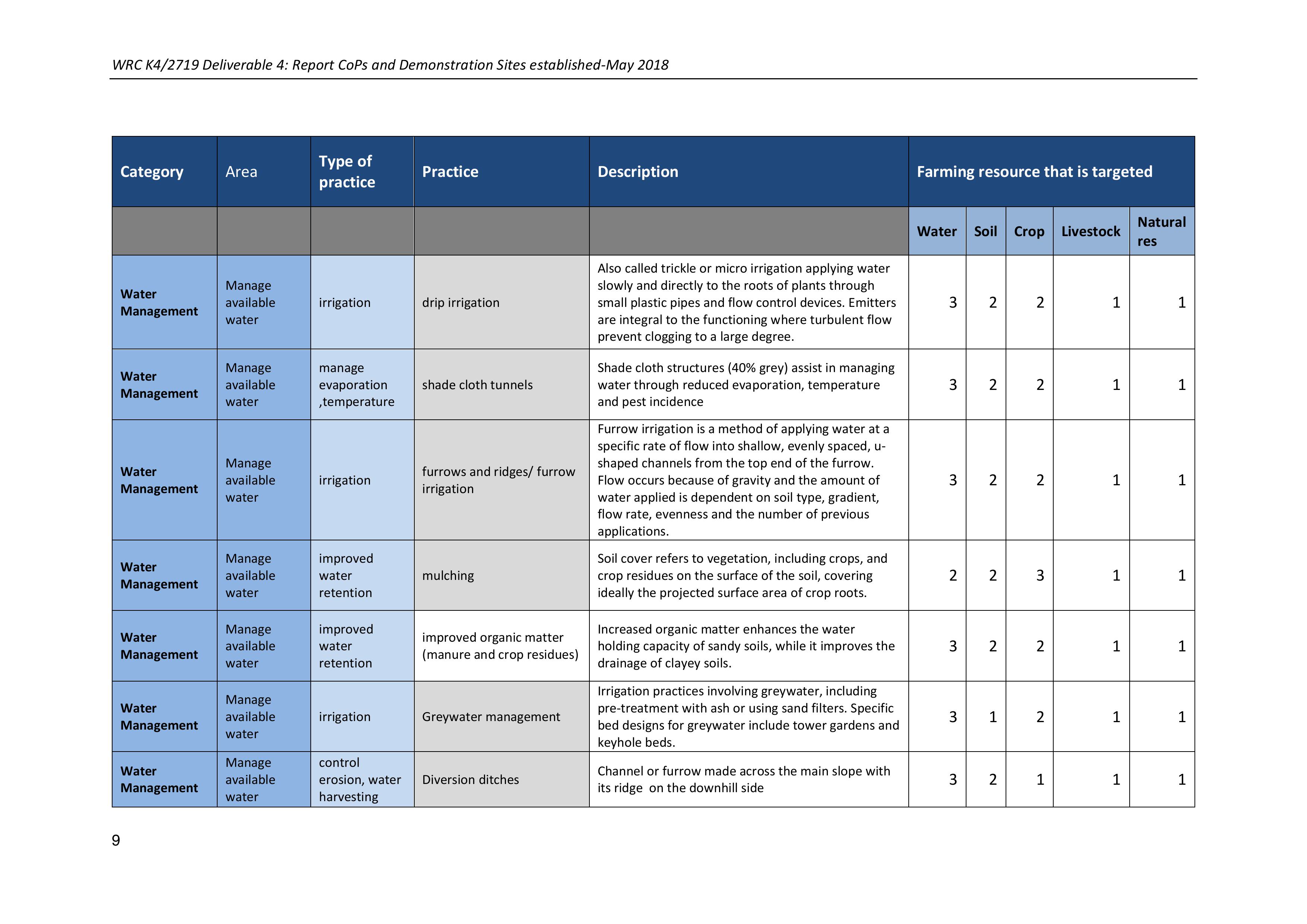

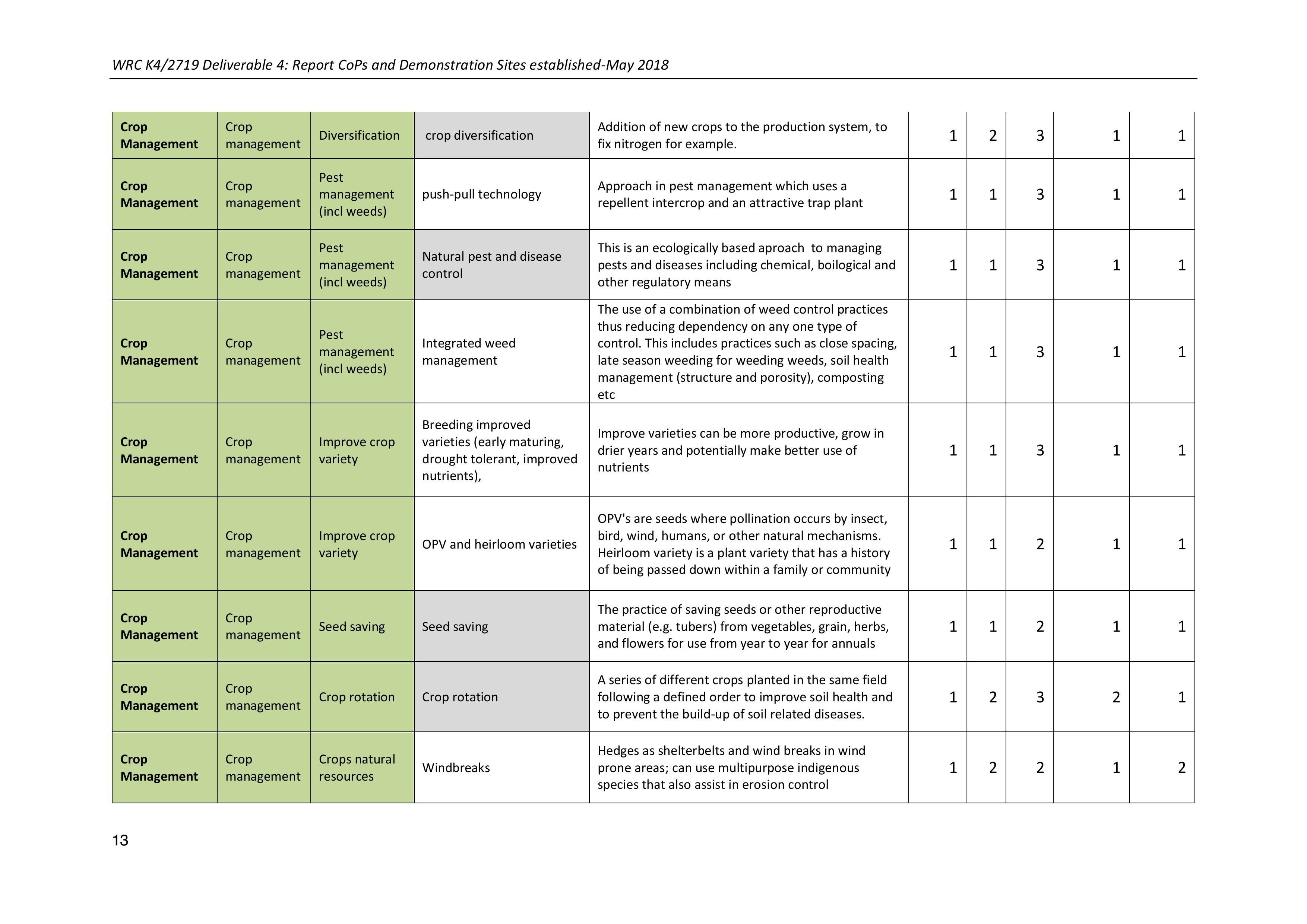

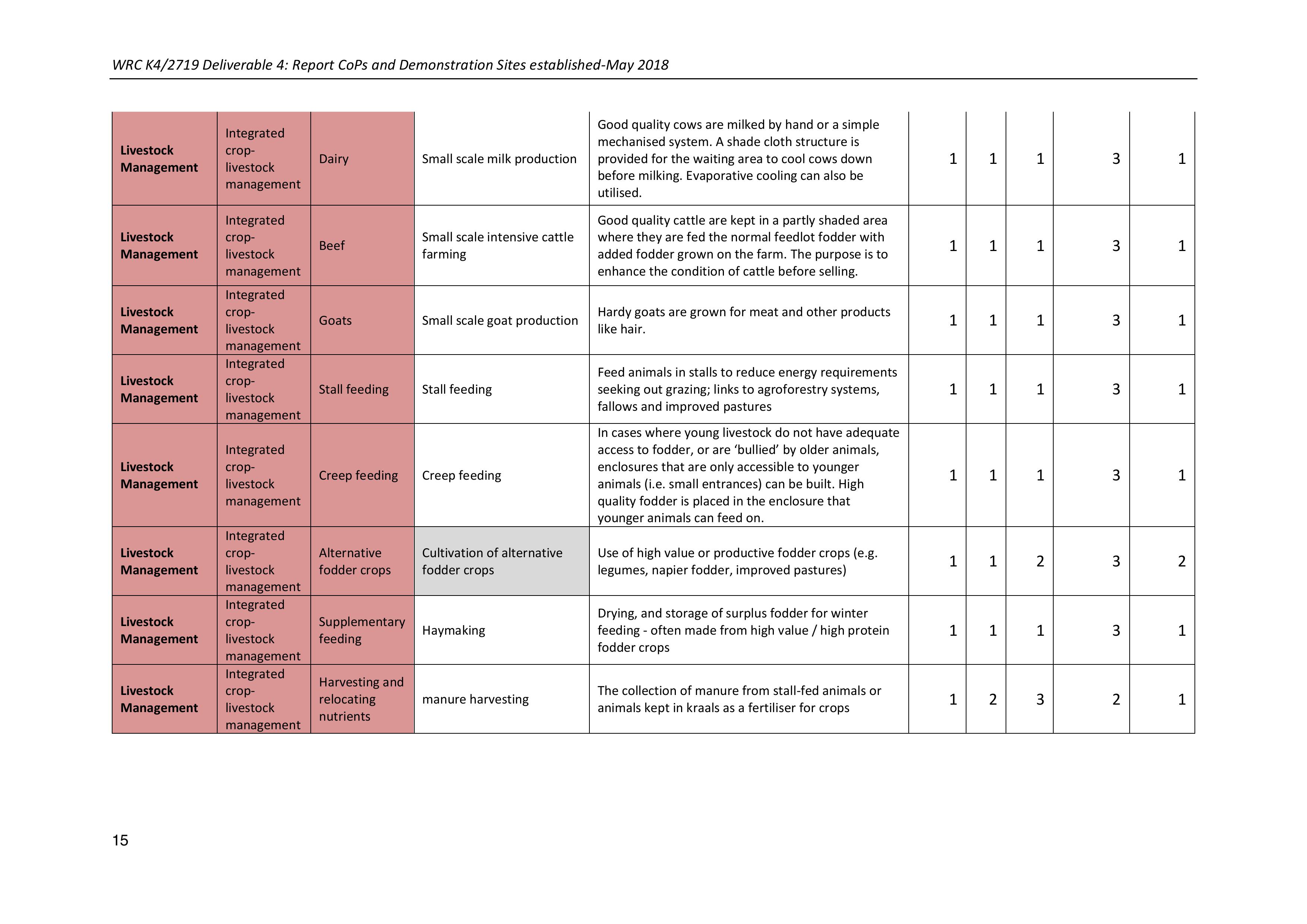

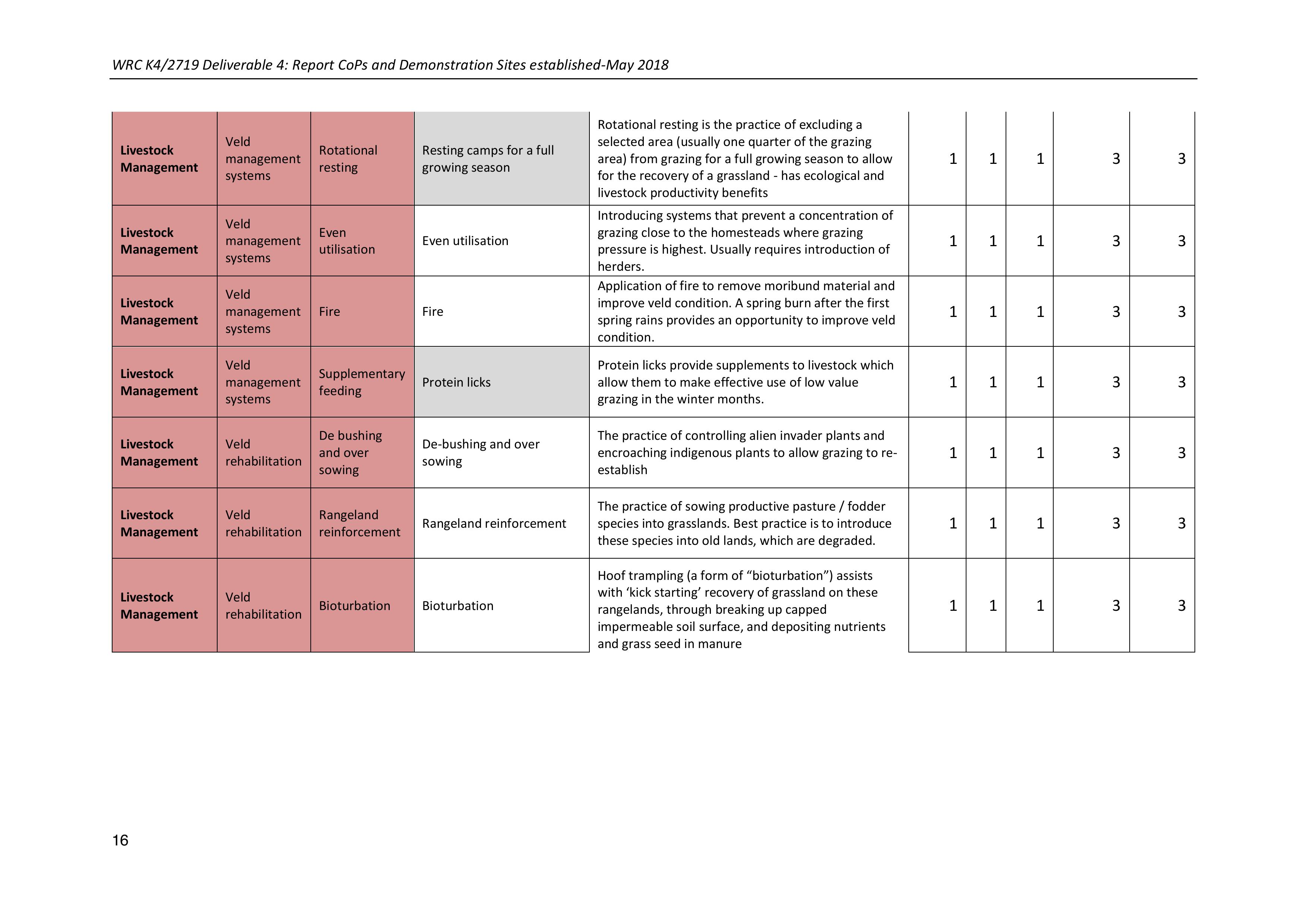

3CSA PRACTICES

A little more work was done on the practices database, providing for a focus on the Agroforestry and

Livestock management options and coming up with the first ideas around these two important

farming system processes.

Province

Site/Area;

villages

Demonstration

sites

CoPs

Collaborative strategies

KZN

Tabamhlophe

- 1st CC workshop

- Collaborative

strategies:

-2nd CC workshop

-Farmers w NGO

support (Lima RDF)

- Tunnels and drip kits

- Individual experimentation

with basket of options

Ezibomvini/

Thamela, Eqeleni

- 1st CC workshop

-Collaborative

strategies

-2nd CC workshop

-CA open days,

cross visits

(LandCare, DARD,

ARC, GrainSA), LM

Agric forums, ….

- Tunnels (Quantitative

measurements

- CA farmer experimentation

(Quantitative measurements)

– case studies

-Individual experimentation

with basket of options

Limpopo

Mametja

(Sedawa, Turkey,

- 1st CC workshop

- 3rd DICLAD

workshop

- Collaborative

strategies:

-Agroecology

network

(AWARD/MDF)

- Tunnels (Quantitative

measurements

- CA farmer experimentation

(Quantitative measurements)

– case studies

- Individual experimentation

with basket of options

Tzaneen

(Sekororo -

Lourene)

- 1st CC workshop

- Collaborative

strategies

-Tunnels and drip kits

EC

Alice/Middledrift

area

- 1st CC workshop

-2nd CC workshop

Imvotho Bubomi

Learning Network

(IBLN) - ERLC, Fort

Cox, Farmers, Agric

Extension services,

NGOs

-Individual and collaborative

experimentation with basket

of options

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

9

Category

Area

Type of

practice

Practice

Description

Farming resource that is targeted

Water

Soil

Crop

Livestock

Natural

res

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

irrigation

drip irrigation

Also called trickle or micro irrigation applying water

slowly and directly to the roots of plants through

small plastic pipes and flow control devices. Emitters

are integral to the functioning where turbulent flow

prevent clogging to a large degree.

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

manage

evaporation

,temperature

shade cloth tunnels

Shade cloth structures (40% grey) assist in managing

water through reduced evaporation, temperature

and pest incidence

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

irrigation

furrows and ridges/ furrow

irrigation

Furrow irrigation is a method of applying water at a

specific rate of flow into shallow, evenly spaced, u-

shaped channels from the top end of the furrow.

Flow occurs because of gravity and the amount of

water applied is dependent on soil type, gradient,

flow rate, evenness and the number of previous

applications.

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

improved

water

retention

mulching

Soil cover refers to vegetation, including crops, and

crop residues on the surface of the soil, covering

ideally the projected surface area of crop roots.

2

2

3

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

improved

water

retention

improved organic matter

(manure and crop residues)

Increased organic matter enhances the water

holding capacity of sandy soils, while it improves the

drainage of clayey soils.

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

irrigation

Greywater management

Irrigation practices involving greywater, including

pre-treatment with ash or using sand filters. Specific

bed designs for greywater include tower gardens and

keyhole beds.

3

1

2

1

1

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Diversion ditches

Channel or furrow made across the main slope with

its ridge on the downhill side

3

2

1

1

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

10

Water

Management

Manage

available

water

control erosion

Grass water ways

Shaped or graded channels with suitable vegetation,

designed to intermittently carry surface water runoff

at non-erosive velocities to stable outlets.

2

3

2

1

1

Water

Management

Increase

available

water

water

harvesting, soil

fertility

infiltration pits / banana

circles

0.7m-1.5m deep pits/basins dug in water flow lines

to control water movement and filled with organic

matter for improved soil fertility. Various planting

regimes including bananas

3

2

3

1

1

Water

Management

Increase

available

water

water

harvesting

rain water harvesting

The collection of run off from rain, roof and other

surfaces for productive use in and outside the field.

Both infield and storage options are available

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Increase

available

water

water

harvesting

tied ridges

Increases the water availability by collecting rainfall

from an unplanted sloping basin and catching it with

a furrow and ridge. Planting takes place on either

side of the furrow where the water has infiltrated.

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Increase

available

water

water

harvesting, soil

erosion control

Half moon basins

These are small semi circular earth bunds for

catching water flowing down a slope

3

2

2

1

1

Water

Management

Increase

available

water

water

harvesting

small dams

2m-5m deep pond constructed to catch water during

the rainy season with a clay core, a wall (for larger

earth dams) and a spillway to let go off excess water

3

2

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control erosion

Contours; ploughing and

planting

Ploughing and or planting along the contours of the

land in order to minimize soil erosion. Can use line

levels, A-frames, dumpy levels etc to mark contours

2

3

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control erosion

gabions

Rectangular baskets fabricated from a hexagonal

mesh of heavily galvanized iron, filled with stones/

gravel for erosion control steel wire filled with rock

and stacked atop one another to form a gravity type

wall.

2

3

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Stone bunds

Used along contour lines to slow down, filter and

spread out runoff water, thus increasing infiltration

and reducing soil erosion.

2

3

2

1

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

11

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

check dams

These are small dams constructed across a drainage

ditch, or waterway to counteract erosion by reducing

water flow velocity and allowing sedimentation of

silt.

2

3

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Swales

Swales are ditches and bunds constructed on

contour to manage water flow and sedimentation.

Mulching and planting occurs in both the ditch and

on the bunds

2

3

3

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Zai pits

Hand dug 0.6m diameter and 0.3m deep circular

holes that collect and store water for crop use

3

2

3

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Terraces

A terrace is a level strip of soil built along the

contour of a slope and supported by an earth or

stone bund, or rows of old tyres for example

2

3

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, water

harvesting

Stone packs

Like gabions and check dams these are constructed

across gulleys or water flow paths to control erosion,

slow surface water flow rate and promote

sedimentation

2

3

2

1

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, crops,

livestock,

natural

resources

Strip cropping

Strip cropping is a strategy for subdividing single

fields on slopes into strips that follow contours;

where different crops are planted; a mixture of

annual and perennial crops are usually used.

2

3

3

2

1

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control erosion

Pitting

Pitting is carried out in large fields or areas prone to

sheet and wind erosion where the whole area is

imprinted with small pits- into which sediment and

seeds can be blown for germination when it rains.

2

3

2

2

2

Soil

Management

Control soil

movement

control

erosion, soil

fertility

Woodlots for soil

reclamation

Trees planted in an eroded area will assist with

recuding the flow rate of surface water and thus help

to prevent further erosion.

1

3

1

1

3

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility

soil nutrients

Targeted application of

small quantities of

fertilizer, lime etc

Use of site specific fertilizer recommendation and

more efficient use of fertilizer (using the right,

source, at right time, at right place and applying the

right rate) , liming to manage soil acidity (surface

liming and incorporation).

2

1

3

1

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

12

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility

soil nutrients

Liquid manures

Brews are made of animal and plant matter as liquid

supplements to soil fertility,

1

1

3

1

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility

soil nutrients,

livestock

fodder

Woody hedgerows for

browse, mulch, green

manure, soil conservation

Growing leguminous tree shrubs in narrow strips

across the slope and material used a green manure

1

2

3

2

2

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

health

manage water,

control erosion

and soil

health, crops,

livestock

Conservation Agriculture

Three main principles of minimal soil disturbance (no

ploughing), soil cover (stover, mulching and cropping

patterns) and diversity ( inter cropping, relay

cropping and cover crops) upheld in the field

cropping system

2

2

3

2

2

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

soil health

soil nutrients

Planting legumes, manure,

green manures

Use of legumes , manures (improved) and green

manures in specific combinations to improve soil

fertility and soil health.

1

2

3

1

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

soil health

soil nutrients,

crops

Mixed cropping

Managing soil health and pest and disease incidence

through crop combinations; mixed cropping, inter

cropping, crop rotation

1

2

3

2

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

soil health

soil nutrients,

crops

Herbs and multifunctional

plants

Managing soil health and pest and disease incidence

through crop combinations; using herbs and

multifunctional plants - including windbreaks, trap

cropping, pest deterrents, bee fodder etc

1

2

3

2

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

health

soil nutrients,

crops,

livestock

Agroforestry options

(multipurpose, fast growing

trees and fodder species)

Land use management system in which trees or

shrubs are grown around or among crops or

pastureland

2

2

3

3

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

health

soil nutrients,

crops

Bed design; trench beds,

eco circles

Intensive beds dug out and filled with a range of

organic matter ( dry, wet manure, bones, ash etc) to

provide for highly fertile beds with high water

holding capacity - e.g. trench beds, shallow trenches,

eco-circles

2

2

3

1

1

Soil

Management

Improve soil

fertility and

health

soil nutrients,

crops

Understand soil health

aspects using visual

indicators

Using visual indicators for soil type, soil aggregates,

porosity, soil mottles, infiltration etc can assist in

planning appropriate soil management structures

1

3

2

1

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

13

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Diversification

crop diversification

Addition of new crops to the production system, to

fix nitrogen for example.

1

2

3

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Pest

management

(incl weeds)

push-pull technology

Approach in pest management which uses a

repellent intercrop and an attractive trap plant

1

1

3

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Pest

management

(incl weeds)

Natural pest and disease

control

This is an ecologically based aproach to managing

pests and diseases including chemical, boilogical and

other regulatory means

1

1

3

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Pest

management

(incl weeds)

Integrated weed

management

The use of a combination of weed control practices

thus reducing dependency on any one type of

control. This includes practices such as close spacing,

late season weeding for weeding weeds, soil health

management (structure and porosity), composting

etc

1

1

3

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Improve crop

variety

Breeding improved

varieties (early maturing,

drought tolerant, improved

nutrients),

Improve varieties can be more productive, grow in

drier years and potentially make better use of

nutrients

1

1

3

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Improve crop

variety

OPV and heirloom varieties

OPV's are seeds where pollination occurs by insect,

bird, wind, humans, or other natural mechanisms.

Heirloom variety is a plant variety that has a history

of being passed down within a family or community

1

1

2

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Seed saving

Seed saving

The practice of saving seeds or other reproductive

material (e.g. tubers) from vegetables, grain, herbs,

and flowers for use from year to year for annuals

1

1

2

1

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Crop rotation

Crop rotation

A series of different crops planted in the same field

following a defined order to improve soil health and

to prevent the build-up of soil related diseases.

1

2

3

2

1

Crop

Management

Crop

management

Crops natural

resources

Windbreaks

Hedges as shelterbelts and wind breaks in wind

prone areas; can use multipurpose indigenous

species that also assist in erosion control

1

2

2

1

2

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

14

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Integrated

systems

Trees and bushes lining fish

ponds for optimal pond

conditions and fish

"browsing"

Trees and shrubs are planted on the edge of the

pond to prevent trampling by cattle. Watering points

need to be provided if the pond is used for stock

watering.

3

1

2

2

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Honey

Trees suitable for honey

production

Trees suitable for honey production could be planted

on field edges and unused areas.

1

1

2

1

2

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Protein rich

trees

Production of protein-rich

tree fodder on

farm/rangelands for cut-

and-carry fodder

production

Protein rich trees like tree Lucerne could enhance

the grazing capacity and assist with soil protection

1

2

2

3

2

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Woodlots

Woodlots for timber,

fodder, soil protection, soil

reclamation

Appropriate trees planted in an eroded area will

assist with reducing the flow rate of surface water

and thus help to prevent further erosion. It will also

enhance the soil fertility because of the falling

leaves.

1

2

2

2

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Improved

fallow

Woodly legumious crops

planted and left to grow

during fallow phase to

improve fallow

Deliberate planting of leguminous species primarily

for fixing nitrogen as part of crop fallow and rotation

and secondarily for livestock fodder

1

2

3

3

2

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Shade

Trees planted for shading

crops or animals

A plantation of one or more rows of trees for

shading purposes. This can enhance the production

of dairy cows significantly - if the waiting area is fully

shaded.

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Broilers

Small scale broiler

production

Grow broilers in naturally ventilated houses made of

iso-wall panels. Free range optional

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Layers

Small scale egg production

Produce eggs in naturally ventilated houses made of

iso-wall panels. Free range optional

1

1

1

3

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

15

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Dairy

Small scale milk production

Good quality cows are milked by hand or a simple

mechanised system. A shade cloth structure is

provided for the waiting area to cool cows down

before milking. Evaporative cooling can also be

utilised.

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Beef

Small scale intensive cattle

farming

Good quality cattle are kept in a partly shaded area

where they are fed the normal feedlot fodder with

added fodder grown on the farm. The purpose is to

enhance the condition of cattle before selling.

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Goats

Small scale goat production

Hardy goats are grown for meat and other products

like hair.

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Stall feeding

Stall feeding

Feed animals in stalls to reduce energy requirements

seeking out grazing; links to agroforestry systems,

fallows and improved pastures

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Creep feeding

Creep feeding

In cases where young livestock do not have adequate

access to fodder, or are ‘bullied’ by older animals,

enclosures that are only accessible to younger

animals (i.e. small entrances) can be built. High

quality fodder is placed in the enclosure that

younger animals can feed on.

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Alternative

fodder crops

Cultivation of alternative

fodder crops

Use of high value or productive fodder crops (e.g.

legumes, napier fodder, improved pastures)

1

1

2

3

2

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Supplementary

feeding

Haymaking

Drying, and storage of surplus fodder for winter

feeding - often made from high value / high protein

fodder crops

1

1

1

3

1

Livestock

Management

Integrated

crop-

livestock

management

Harvesting and

relocating

nutrients

manure harvesting

The collection of manure from stall-fed animals or

animals kept in kraals as a fertiliser for crops

1

2

3

2

1

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

16

Livestock

Management

Veld

management

systems

Rotational

resting

Resting camps for a full

growing season

Rotational resting is the practice of excluding a

selected area (usually one quarter of the grazing

area) from grazing for a full growing season to allow

for the recovery of a grassland - has ecological and

livestock productivity benefits

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

management

systems

Even

utilisation

Even utilisation

Introducing systems that prevent a concentration of

grazing close to the homesteads where grazing

pressure is highest. Usually requires introduction of

herders.

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

management

systems

Fire

Fire

Application of fire to remove moribund material and

improve veld condition. A spring burn after the first

spring rains provides an opportunity to improve veld

condition.

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

management

systems

Supplementary

feeding

Protein licks

Protein licks provide supplements to livestock which

allow them to make effective use of low value

grazing in the winter months.

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

rehabilitation

De bushing

and over

sowing

De-bushing and over

sowing

The practice of controlling alien invader plants and

encroaching indigenous plants to allow grazing to re-

establish

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

rehabilitation

Rangeland

reinforcement

Rangeland reinforcement

The practice of sowing productive pasture / fodder

species into grasslands. Best practice is to introduce

these species into old lands, which are degraded.

1

1

1

3

3

Livestock

Management

Veld

rehabilitation

Bioturbation

Bioturbation

Hoof trampling (a form of “bioturbation”) assists

with ‘kick starting’ recovery of grassland on these

rangelands, through breaking up capped

impermeable soil surface, and depositing nutrients

and grass seed in manure

1

1

1

3

3

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

17

Further practices suggested by local farmers

The practices mentioned below are to be added into the database of practices

-Spring protection

-Biogas digesters

-Different seed varieties

-Planting calendars

-Drought tolerant and bird resistant varieties

-Lizard hotel

-More on greywater management

4OUTCOMES OF CC DIALOGUES (WORKSHOP 1): DEFINITIONS,

CHANGES, PRESENT ACTIVITIES, IMPACTS

Initial Climate Change dialogues, to explore concepts of climate change, the impacts on peoples’ lives

and farming activities and tostart discussions on potential adaptive strategies in these communities

have been undertaken for 7 villages across three provinces. Full reports for a number of these

workshops are attached in Appendices 2-5.

Here a summary of some of the outcomes and discussions will be provided.

Overview

It can be considered that farmers always complain about the weather; especially those reliant on the

weather for crop and livestock production. This meant that our first topic revolved around the

differences between general weather variability and climate change. This was achievedthrough role

plays, slide shows and discussions.

The situation differs across the provinces:

-In Limpopo; there was consensus among participants that it is generally hotter throughout

the whole year than it was in the past (10 years ago) and that they are receiving less rain

than before. They feel that the impact of the recent drought has been a lot more severe

because of these conditions.

-In KZN; farmers are aware of changes in rainfall patterns. They experience more extreme

events (storms, high winds and hail) than before. Temperature variability has also increased

with cold weather at unexpected times, snow both earlier and later than usual in the season

and excessive heat in spring, summer and autumn.

-In the EC; farmers are aware of changes in rainfall patterns. They experience more extreme

events (storms, high winds and hail) than before. They feel that winters are colder than

before. There is greater temperature variability from day to day than before.

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

18

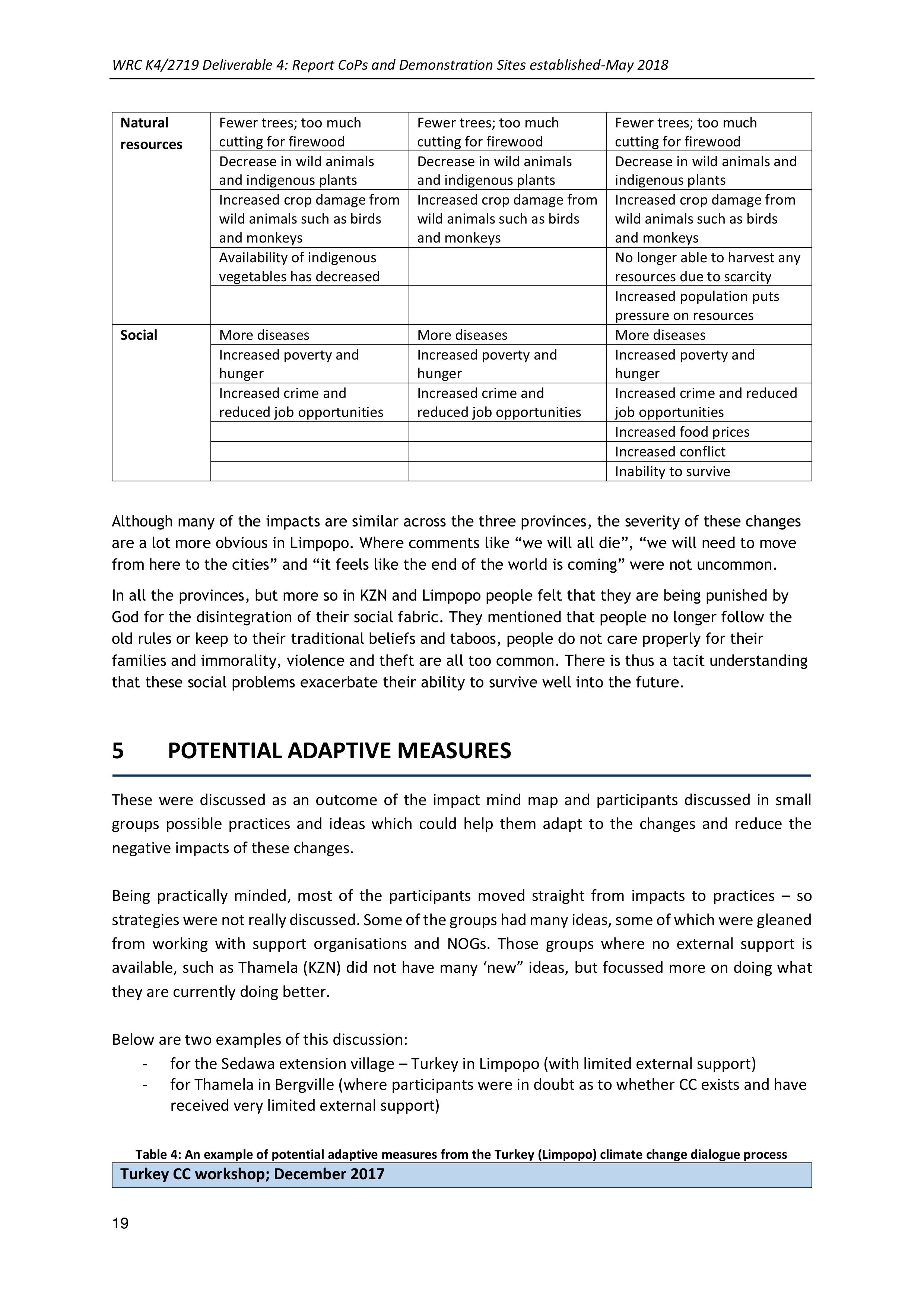

Impacts of CC on livelihoods and farming

These impacts were first discussed in general terms, then reviewed in terms of comparingthe past

present and future and then interrogated using the impacts mind mapping process.

The table below outlines a summary of impacts mentioned for each province

Table 3: Summary of climate change impacts from community level workshops

Climate change impacts on livelihoods and farming

KZN

EC

Limpopo

Water

Less water in the landscape;

streams and springs dry up,

borehole run dry, soils dry

out quickly after rain

Less water in the landscape;

streams and springs dry up,

borehole run dry, soils dry

out quickly after rain

Less water in the landscape;

streams and springs dry up,

borehole run dry, soils dry

out quickly after rain

Dams dry up

Dams dry up

Dams dry up

Municipal water supply

becoming more unreliable

Municipal water supply

becoming more unreliable

Municipal water supply

becoming more unreliable;

Need to buy water for

household use – now

sometimes for more than 6

months of the year

RWH storage only enough for

household use.

Soil

More erosion

More erosion

More erosion

Soils becoming more

compacted and infertile

Soils becoming more

compacted and infertile

Soils becoming more

compacted and infertile

Soils too hot to sustain plant

growth

Cropping

Timing for planting has

changed- later

Timing for planting has

changed- later

Can no longer plant dryland

maize

All cropping now requires

irrigation – even crops such

as sweet potato

Drought tolerant crops such

as sorghum and millet grow=-

but severe bird damage

Heat damage to crops

Heat damage to crops

Heat damage to crops

Reduced germination and

growth

Reduced germination and

growth

Reduced germination and

growth

Seeding of legumes

becoming unreliable

Seeding of legumes

becoming unreliable

Seeding of legumes becoming

unreliable

Lower yields

Lower yields

Lower yields

Winter vegetables don’t do

well -stress induced bolting

and lack of growth

More pests and diseases

More pests and diseases

More pests and diseases

Loss of indigenous seed

stocks

Loss of indigenous seed

stocks

Livestock

Less grazing; not enough to

see cattle through winter

Less grazing; not enough to

see cattle through winter

Less grazing; not enough to

see cattle through winter

More disease in cattle and

heat stress symptoms

More disease in cattle and

heat stress symptoms

More disease in cattle and

heat stress symptoms

Fewer calves

Fewer calves

Fewer calves

More deaths

More deaths

More deaths

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

19

Natural

resources

Fewer trees; too much

cutting for firewood

Fewer trees; too much

cutting for firewood

Fewer trees; too much

cutting for firewood

Decrease in wild animals

and indigenous plants

Decrease in wild animals

and indigenous plants

Decrease in wild animals and

indigenous plants

Increased crop damage from

wild animals such as birds

and monkeys

Increased crop damage from

wild animals such as birds

and monkeys

Increased crop damage from

wild animals such as birds

and monkeys

Availability of indigenous

vegetables has decreased

No longer able to harvest any

resources due to scarcity

Increased population puts

pressure on resources

Social

More diseases

More diseases

More diseases

Increased poverty and

hunger

Increased poverty and

hunger

Increased poverty and

hunger

Increased crime and

reduced job opportunities

Increased crime and

reduced job opportunities

Increased crime and reduced

job opportunities

Increased food prices

Increased conflict

Inability to survive

Although many of the impacts are similar across the three provinces, the severity of these changes

are a lot more obvious in Limpopo. Where comments like “we will all die”, “we will need to move

from here to the cities” and “it feels like the end of the world is coming” were not uncommon.

In all the provinces, but more so in KZN and Limpopo people felt that they are being punished by

God for the disintegration of their social fabric. They mentioned that people no longer follow the

old rules or keep to their traditional beliefs and taboos, people do not care properly for their

families and immorality, violence and theft are all too common. There is thus a tacit understanding

that these social problems exacerbate their ability to survive well into the future.

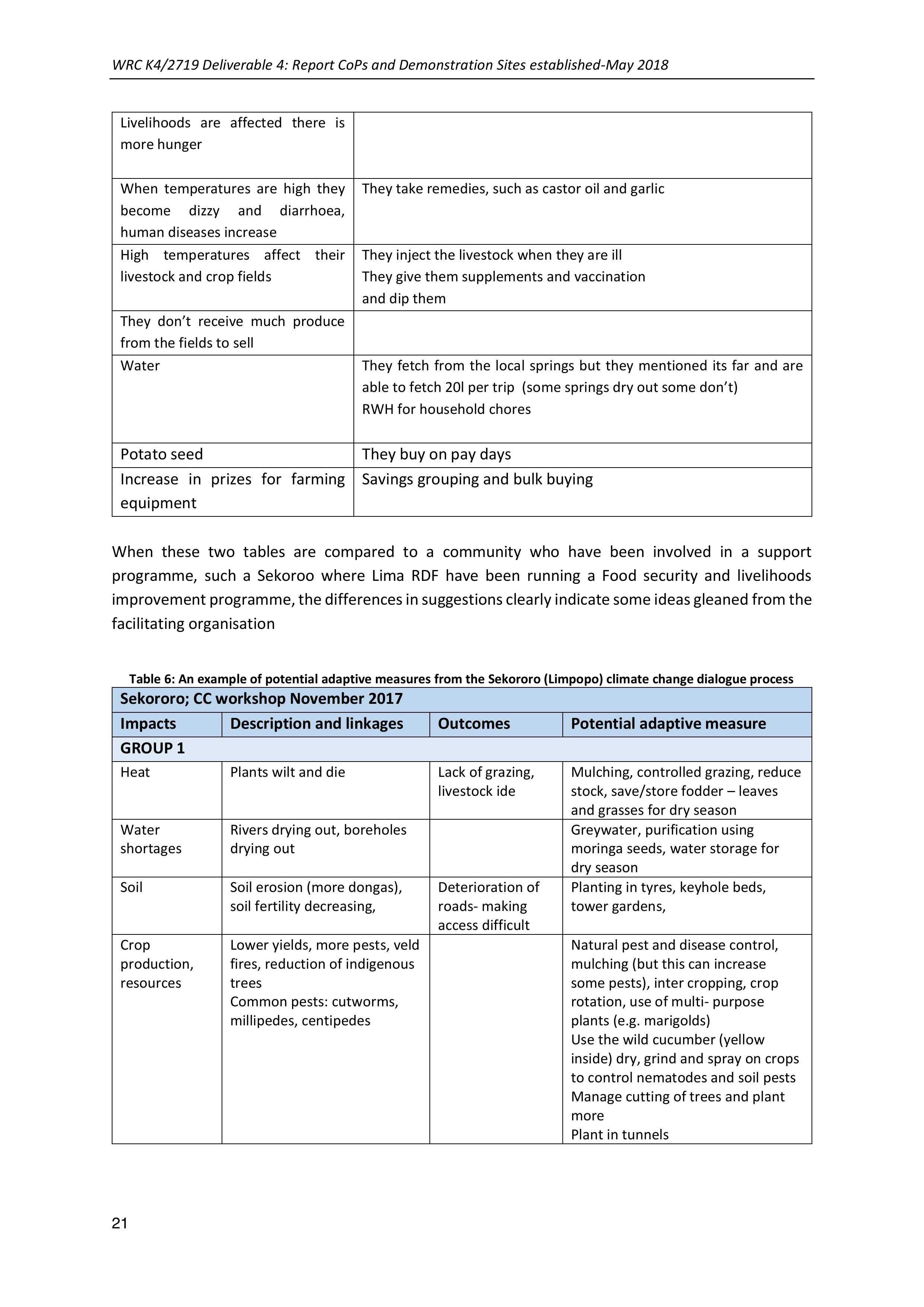

5POTENTIAL ADAPTIVE MEASURES

These were discussed as an outcome of the impact mind map and participants discussed in small

groups possiblepracticesand ideaswhich couldhelp them adapt to the changes and reduce the

negative impacts of these changes.

Being practically minded, most of the participants moved straight from impacts to practices –so

strategies were not really discussed. Some of the groups had many ideas, some of which were gleaned

from working with support organisations and NOGs. Those groups where no external support is

available, such as Thamela (KZN) did not have many ‘new” ideas,but focussed more on doing what

they are currently doing better.

Below are two examples of this discussion:

-for the Sedawa extension village – Turkey in Limpopo (with limited external support)

-for Thamela in Bergville (where participants were in doubt as to whether CC exists and have

received very limited external support)

Table 4: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Turkey (Limpopo) climate change dialogue process

Turkey CC workshop; December 2017

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

20

Impacts

Description and linkages

Outcomes

Potential adaptive measure

GROUP 1

Reduced

water

availability

Dams dry out, boreholes

provide less water, rivers dry

out, less rain

Reduced

production,

hunger, diseases,

no jobs, poverty,

crime, death

More boreholes, more dams, water

management, irrigation in evenings

and early morning, mulching, trench

beds (keep moisture in and soil cool)

Drying of

environment

Soils are hotter and drier,

drought, plants wilt,

increased pests

Save plant residues for animals, buy

fodder, control pests on animals

Reduction of

resources

Deforestation, Fruit trees die,

livestock, wild animals die

Planting of trees after they have

been cut down; make use of paraffin

stoves and electricity, government

involvement in solving the problem,

GROUP 2

Extreme heat

Early fruiting, trees wilt

Poor crop health

Shade netting

Shortage of

water

Rivers dry out, municipal

supply only once per week.

Boreholes dry out

Lack of education

towards saving

water

NGOs and government to assist

Trench beds, mulching, save water

in dams, drip irrigation, irrigate in

evening, boreholes, greywater

Reduction of

resources

Less grazing, seed shortage,

trees are removed,

indigenous animals are no

longer there

Donations for/of seed

Rather use paraffin stoves than

firewood. Only chop down mature

trees to allow others to grow,

planting trees, government

intervention

Taking care of indigenous plants

Plant fodder for livestock

Soils

Poor cultivation practices, soil

erosion, dry soils, sandy soils

Using crop residues and manure

Social

repercussions

Less or no food, health

problems, no jobs

Burning of buses,

divorce,

separation of

families, poverty,

crime

Getting access to health care,

parents must work

Shortage of

implements

Setting up cooperatives for

government support, use animal

drawn traction- oxen and donkeys,

improvise, make our own tools,

make use of hand hoes

Table 5: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Thamela (KZN)) climate change dialogue process

Thamela CC workshop; Dec 2017

Impact

Adaptation

Reddish soils

Weeding, they leave it in the plots, because it helps cover the soil but

others they take it out of their plots

Pests

Chemicals

Increased temperatures our yields

decrease

Their crops need soil fertilizer,

oFertilizer increase soil fertility

oLime lasts for 3 years

oManure

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

21

Livelihoods are affected there is

more hunger

When temperatures are high they

become dizzy anddiarrhoea,

human diseases increase

They take remedies, such as castor oil and garlic

High temperatures affect their

livestock and crop fields

They inject the livestock when they are ill

They give them supplements and vaccination

and dip them

They don’t receive much produce

from the fields to sell

Water

They fetch from the local springs but they mentioned its far and are

able to fetch 20l per trip (some springs dry out some don’t)

RWH for household chores

Potato seed

They buy on pay days

Increase inprizes for farming

equipment

Savings grouping and bulk buying

When these two tables are compared to a community who have beeninvolved in a support

programme, such a Sekoroo where LimaRDF have been running a Food security and livelihoods

improvement programme, the differences in suggestions clearly indicate some ideas gleaned from the

facilitating organisation

Table 6: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Sekororo (Limpopo) climate change dialogue process

Sekororo; CC workshop November 2017

Impacts

Description and linkages

Outcomes

Potential adaptive measure

GROUP 1

Heat

Plants wilt and die

Lack of grazing,

livestock ide

Mulching, controlled grazing, reduce

stock, save/store fodder – leaves

and grasses for dry season

Water

shortages

Rivers drying out, boreholes

drying out

Greywater, purification using

moringa seeds, water storage for

dry season

Soil

Soil erosion (more dongas),

soil fertility decreasing,

Deterioration of

roads- making

access difficult

Planting in tyres, keyhole beds,

tower gardens,

Crop

production,

resources

Lower yields, more pests, veld

fires, reduction of indigenous

trees

Common pests: cutworms,

millipedes, centipedes

Natural pest and disease control,

mulching (but this can increase

some pests), inter cropping, crop

rotation, use of multi- purpose

plants (e.g. marigolds)

Use the wild cucumber (yellow

inside) dry, grind and spray on crops

to control nematodes and soil pests

Manage cutting of trees and plant

more

Plant in tunnels

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

22

Livestock

Lack of grazing, more

diseases, more damage of

crops

Livestock

decreasing, not

healthy

Control grazing,

Social

repercussions

Poverty, diseases, hunger

Crime, murder

and theft,

domestic

violence, divorce,

increased death

rate, no money to

pay lobola

GROUP 2

Extreme heat

Veld fires

Use of tunnels, plant heat resistant

cultivars, irrigate in early mornings

and evenings

Lack of water

No grazing, drying of natural

vegetation and bushes,

wilting of plants, trees do not

fruit, extreme rains destroy

infrastructure,

Food shortages,

animals die due to

lack of grazing,

Water harvesting, earth dams, grey

water and management of existing

water, diversion furrows

Soils

Organic matter content is

low, dry soils, roots are

exposed, soil erosion, also

due to use of mechanisation -

ploughing

Liquid manure, make use of animal

manure, trench beds and eco-circles

Plant sweet potatoes to hold soil,

plant across the slope, plant

indigenous crops such as cowpeas,

Make use of hands and oxen to

plant using conservation agriculture

Loosen the soil to avoid water

logging and yellowing of plants

Crops

Reduced production

increased pests, medicinal

herbs destroyed in drought

and heat

Plant colourful flowers and plants to

attract pest predators and bees,

companion planting, making brews

form marigolds

Plant medicinal species in controlled

environments with the vegetables

9tunnels)

Social

repercussions

More diseases and health

problems, poverty food

shortages, low education

standards (because schools

are free)

No transfer of

knowledge, crime

Plant herbs and vegetables,

entrepreneurship, job creation,

plant your own crops instead of

always buying

Based on the adaptive measures suggested a selection of the CSA practices summarised as 1 pagers

were introduced to each group. This process was easy for groups that have had some exposure to

agroecological practices and support in implementation and a lot harder where little outside support

has been available.

6CONTINUATION OF CC DIALOGUES (WORKSHOP 2): POTENTIAL

ADAPTIVE MEASURES, PRIORITISATION OF PRACTICES AND

EXPERIMENTATION PLANNING

An outline has been designed for this process and is presented in the table below.

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

23

Table 7: 2nd CC workshop agenda outline

Community level climate change adaptation: Prioritisation and planning workshop outline

DAY 1

Time

Activity

Process

Notes

Materials

Who

9:00am

INTRODUCTION

9:00-

10:00am

Community and

team

introductions

In pairs, take 5 minutes

to talk to each other.

Each person names one

practice they know or

are doing that is good

for CCA - a CSA practice.

OR one they would

most like to try out.

Practices to be

summarised on a

flip chart.

Attendance

register -

with column

for CSA

practices - in

English and

Zulu/Pedi.

Name tags;

stickers, kokis

Preparation:

Facilitation:

Recording:

Purpose of the

day

Introduction of the

organisation/s and

purpose of this

workshop-Review of

understanding of CC,

Impacts and adaptive

measures. Introduction

to CSA principles

Summarise from

report of 1st

workshop -Use

the 5 categories -

summarise

measures under

each. Use two PP

slides attached

Flip stand,

newsprint,

kokis,

camera- and

one person to

undertake to

take photos

throughout

the day. Extra

batteries for

camera and

sim card

Preparation:

Facilitation:

Recording:

10:00am

Prioritization of

practices

10:00 to

11:00am

Review practices

mentioned in

detail - both

community level

and presented

from 1pgers

Divide into small groups

- for prioritization

matrix; Use five

categories (Nat res, soil,

water, crop, livestock).

Supply with cards

where all prioritized

practises are written.

They then prioritize

these in a list under

each category, based on

what to try first, second

and so on - make sure

the criteria used for

these choices are

recorded. Come back

in plenary, present and

get overall choices

summarised for all

small groups

See Community

level

prioritization of

practices Excel

worksheet

Flipchart

paper, kokis,

cards with all

prioritized

practices

written out,

pres-stick

Preparation:

Facilitation:

Recording:

11:00 -

11:30am

TEA

Fruit (apples, oranges, biscuits, juice and water, paper cups

(lots) and plates… Generous helpings - and lots of juice if it is

hot. Find someone to be in charge of food and refreshments,

while the rest of the workshop continues

Preparation:

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

24

11:30

Demonstrations

and learning

11:30-

2:30pm

Learning and

practical

demonstration

session on a

selection of

practices - start

with gardening

practices

(appropriate for

present season)

Presentation to group -

discussions etc , then

practical

demonstrations in an

appropriate garden -

preferable a household

garden. Choose 1-4

practices: e.g. trench

bed, mulching, liquid

manure, intercropping

Facilitators to come prepared

with handouts and learning

materials. Also materials for doing

the practical demonstrations such

as mulch, manure, seed,

seedlings, tools, and other e.g.

shade netting, poles, gravel and

ash for tower gardens - depends

on practices and must be planned

for

Preparation:

Facilitation:

Recording:

2:30pm

Individual

experimentation

2:30-

3:00pm

Individual choice

of practices for

household

experimentation

After the

demonstrations - Make

a list for individuals to

choose experiments to

try out. Headings are

practises. Each

participant writes their

name under the

practices they will try -

it can be one, a few or

all.

facilitators to discuss how an

experiment works - ie the farmer

compares the new idea to her

usual practice. For example if she

will do a trench bed, she has to

make a bed new to it the same

size the way she usually does and

plant both in the same way on the

same day.. This way she will be

able to see the differences in

growth and yield from her

practice. She needs to monitor

how it is going and be able to

report back to this group what

has happened.

Preparation:

Facilitation:

Recording:

3:00pm

LUNCH Local catering groups to provide meals - ~R45 per head (Rice and stew

with one veg… or something similar- )

Preparation:

Initial Climate Change dialogues, to explore concepts of climate change, the impacts on peoples’ lives

and farming activities and tostart discussions on potential adaptive strategies in these communities

have been undertaken for more than

1

7 villages across three provinces.

Table 8:Climate change dialogues; workshops 1 and 2.

Province

AREA

VILLAGE

No of participants:

Workshop 1: CCA

No of participants:

Workshop 2:

Practices

Limpopo

Mametja

Turkey

74

Sedawa

24

Tzaneen

Sekororo

30

KZN

Bergville

Thamela

15

2

Ezibomvini/Eqeleni

21

27

Estcourt

Tabamhlophe

19

15

1

The IBLN in the EC covers +/- 10 villages

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

25

EC

Alice/Middledrift

Imvotho Bubomi

Learning Network

(IBLN) - across a

number of villages

15

42

Ezibomvini (KZN) CCAworkshop 2

Below is a summary of some of the

discussions undertaken for the 2ndCC

dialogue workshop undertaken in Ezibomvini

(23 March 2018)

The second workshop, aiming at prioritizing

practice options enlisted in the first work

shop and thereafter starting a farmer's level

experimentation process.

Right: 29 Participants in the 2nd CC dialogue

workshop in Ezibomvini (KZN), 23 March

2018

CCA practices that are familiar to farmers

An introduction session over five minutes took place where farmers were to introduce each other

and their farming activities. Following is the summary of the results from the discussions:

•The use drip irrigation to retain moisture for a long time in the soil.

• Grey water harvesting practice.

•Use of cow manure

•Mulching

•Intercropping

•Bed design

•Rain Water harvesting

•Watering the garden before sunrise and after sunset

•Blue death as pest and disease control measure

•Conservation Agriculture (CA).

oCA farmers receive more yields, the level of pests such as stalk borer and cutworm

has decreased. Farmers are saving on inputs.

Review of participants understanding of Climate change

Farmers still remember that previously there was discussion that historically there is a change in

climate as compared to the current situation. The level of rainfall is now lower and temperatures

are high. The increase in temperature has a negative impact on crop growth. There is the high level

of wind which dries the soils. Historically it was only windy in winter and presently it is windy

throughout. There are no wetlands anymore because there is no rain and people are building houses

where there were wetlands.

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

26

The impact of Climate Change on farmer’s livelihoods

•The outbreak of pests and diseases

There is an outbreak of pests such as aphids, termites, and cutworms, which farmers do not know

how they can solve this problem. Some farmers have ants in their gardens and they used blue death.

•Shortage of animal feed

The high temperatures lead to dry conditions, therefore there is a minimum vegetation growing and

available for livestock to graze on the grazing lands.

•Burning of Grazing veld

Different farmers have the different reason to burn the veld, some burn it to dispose of the straws

left after grazing so that the field can be ready for the following spring, and some burn it for soil

fertility and health purposes. At the end of the day burning of fields leads to disease outbreak to

livestock. Previously our great grand fathers were creating fire banks so that fires do not spread all

over, in nowadays males are lazy and they do not do that.

•Shortage of grazing lands

The population is increasing at an alarming rate, more people are building houses and this has led to

the building of houses in the grazing lands.

CSA practices that were suggested by farmers on the previous workshop

The following table outlines the practices and their categories

Table 9: Suggested practices for farmers, categorised into the 5 primary themes.

Natural RM

Soil

Water

crops

Livestock

1.Tunnels

2.Bed design

3.Mulching

4.Natural pest

and diseases

5.Rainwater

harvesting

6.Trench bed

7.Composting

8.Fodder crops

9.Underground

water tank

10.Mixed

cropping

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

27

11.Conservation

of wetlands

and streams

12.Burying of

disposable

pampers

13.Reducing

burning of

grazing veld

14.Greywater

Harvesting

Group Prioritisation of practices

After a presentation of practices, farmers prioritized practices as a team. Due to drought conditions

problems the group chose underground water tanks as the first priority. Due to harsh weather

conditions farmers chose tunnels as their second option. The following table shows farmers how

farmer prioritised practices.

Individual choice of practical household experimentation

Farmers were given a variety of seeds. All farmers were given sachets with the amount 5ml

(teaspoon) seeds. The seeds were given to farmers so that they can experiment some of the

practices shared among them in their household.

Out of 29 farmers who were present, 20 farmers considered trench beds as their priority. Farmers

who chose trench bed will therefore also try out mixed cropping and mulching. Most of the farmers

Above: Tema facilitating the prioritization of

practices

Group Priority

1. Underground water tanks

2. Tunnels

3. Trench beds

4. Mulching

5. Pest and disease control

6. Mixed cropping

7. Compost

8. Fodder crops

9. Conserving wetlands and streams

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

28

from the nine left already has trench beds in their homesteads. The following is the list of

participants who considered a trench bed as their first priority.

Table 10: Individual volunteers for trench bed experimentation in KZN (Bergville)

Name

Village Name

1.Jabulile Nkabinde

Ezibomvini

2.Fikile Hlongwane

Ezibomvini

3.Nonhlahla Zikode

Ezibomvini

4.Landiwe Gamede

Ezibomvini

5.Gcinekile Zikode

Ezibomvini

6.Hlengiwe Ndaba

Ezibomvini

7.Busisiwe Zikode

Ezibomvini

8.Alfred Gumede

Ezibomvin

9. Velephi Zimba

Ezibomvini

10.Sizeni Dlamini

Eqeleni

11.Lndokuhle Hlongwane

Ezibomvini

12.Conastance Hlongwane

Thamela

13.Thulile Zikode

Eqeleni

14.Sibongile Zikode

Eqeleni

15.Dambi Ntuli

Thamela

16.Zanele Hlongwane

Thamela

17.Thokozile Mpambo

Eqeleni

18.Nomalanga Khumalo

Eqeleni

19.Mvelo Zikode

Ezibomvini

20.Sdudla Sibiya

Ezibomvini

Conclusion and Recommendations

•As mentioned earlier, the weather was not favourable for the workshop field

demonstration, therefore the activity was not done. Demonstrations will be done in the

small group within the individual community. This means that the demonstration will not be

done in a collective group of Ezibomvini, EQeleni, and Thamela, but there is going to be an

individual demonstration for each community.

•On the individual prioritization, most farmers demonstrated an interest in trying trench

beds. It is assumed that most farmers are hoping that if they prepare trench beds they will

be in high chances to get a tunnel, more clarity should be made to farmers regarding tunnels

availability after having trench beds.

•Farmers have expectations to be given free tanks, and it was further clarified to them that

the program is based on transferring knowledge.

•Farmers are not certain about individual priorities, therefore, there is a need for an

assessment of individual's needs.

•More demonstrations and workshops are still needed to strengthen farmers understanding

on Climate change and Climate Smart Agriculture Practices.

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

29

Alice (Eastern Cape) CCA Workshop

This workshop was intended to explore further the particular CSA practices in which farmers were

interested, and with which they wished to experiment with the support of the WRC-CSA project

team. While this aim was achieved to a considerable degree, the large numbers of participants (42

people registered), many of whom had not been involved with Phase I required that some time was

spent introducing the whole concept of CSA. Of the 42 registered participants, in addition to 17

farmers, there were numbers of students some of whom did not remain throughout the day.

However, the attendance by the Head of Department for Crop Production at Fort Cox, and the

Agribusiness Diploma Course leader together with several of their students, suggests a very strong

interest in the concept of CSA in the college. There were also 5 members of the Eastern Cape

Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Reform (DRDAR) extension services in

attendance.

Given the difference in context between the Eastern Cape situation, where the project is working

with a broad network (the IBLN) of agricultural practitioners, including some commercial-scale

emerging farmers, as opposed to in other provinces where the WRC-CSA project works almost

exclusively with small-scale and household farmers, the programme followed was an adaptation of

that followed elsewhere and outlined in Table 7, above. However, the same key features were

covered, and it included a highly participatory practical activity.

The purpose and scope of the WRC-CSA project was explained, including the farmer experimentation

approach which would require close monitoring of both areas subject to CSA practices and control

plots without these practices.

The first session laid the ground for a group activity in which the participants divided into 4 groups,

each with a computer and the pdf version of the WRC- CSA Practices document. Their brief was to

go through the document and identify which practices they would consider most appropriate in their

contexts and why. Each group provided feedback on the outcomes of their discussions with the

practices they had identified captured on Newsprint. There

was discussion concerning the scales at which specific

practices might be appropriate and it transpired that

although most practices were initially considered as only

relevant at smaller scales, they could be scaled up in

different ways to become relevant on a larger scale.

Right: EC Group discussion on CSA Practices

Table 1, below, represents the outcomes of this activity, combined with the numbers of individual

participants who later identified specific practices in which they were interested in the register.

Table 11:CSA Practices: Prioritization by groups and individuals

NOTE: Groups in this case are the small groups in the workshop settingconsisting of homestead

gardeners, cooperative members and more commercial farmers

WRC K4/2719 Deliverable 4: Report CoPs and Demonstration Sites established-May 2018

30

Practice

Scale(s) (Small – homestead,

Medium <1ha, Large >1ha)

No of Groups

No of

Individuals

Swales

All

1

3

Greywater

Small

1

Small Dams

S/M

1

Fertility Pits

S/M

1

Contours

M/L

1

Terraces

ALL

1

Furrows/Ridges

All

0

1

Infiltration pits/

Banana Circles

Small

1

2

Raised Beds

All (considerable discussion here, with

some saying just S/M)

1

Trench Beds

S/M

1

Tower Gardens

S

1

3

Tunnel

All

1

2

Basins/In-field

All

1

1

Mulching

All

4

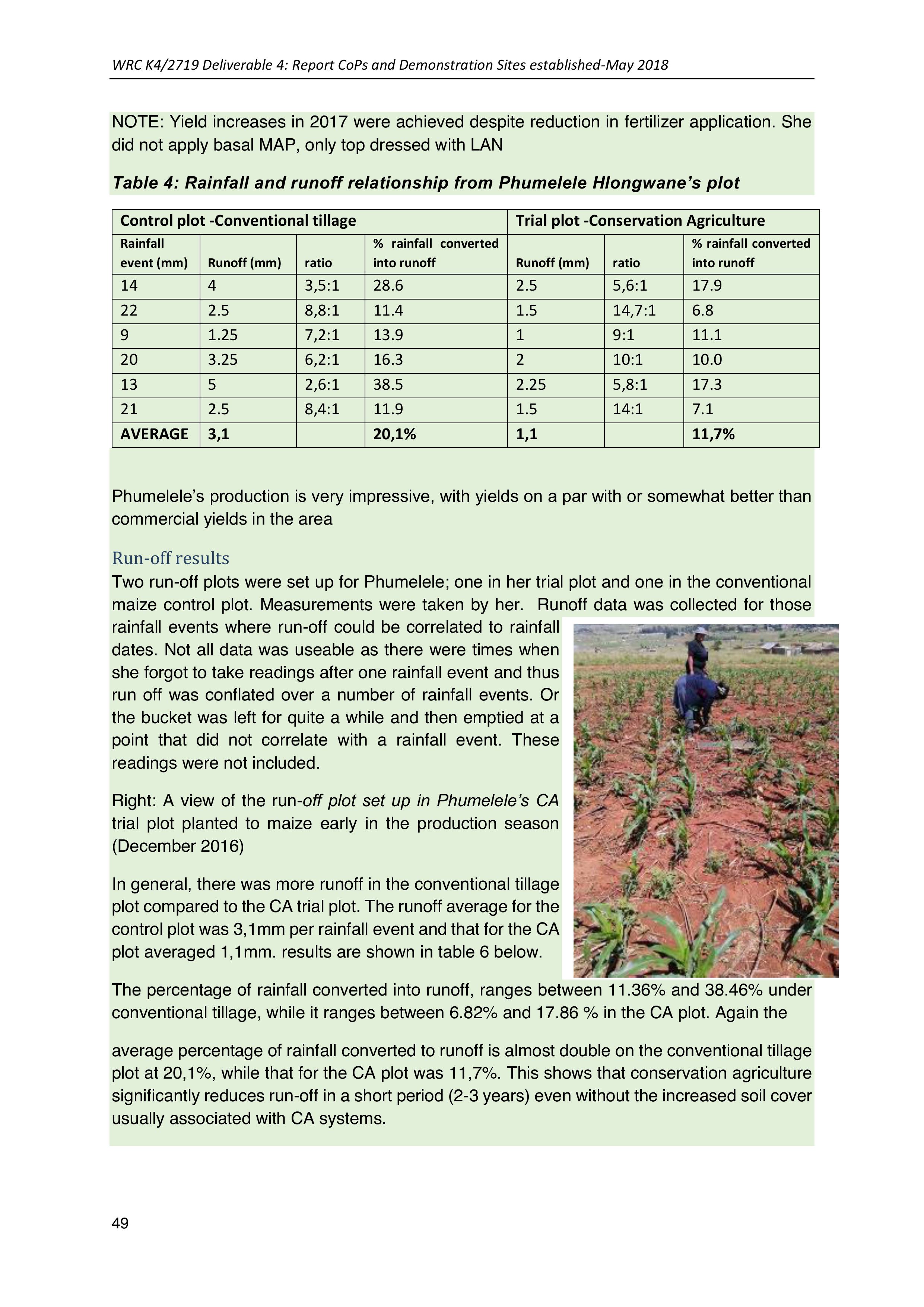

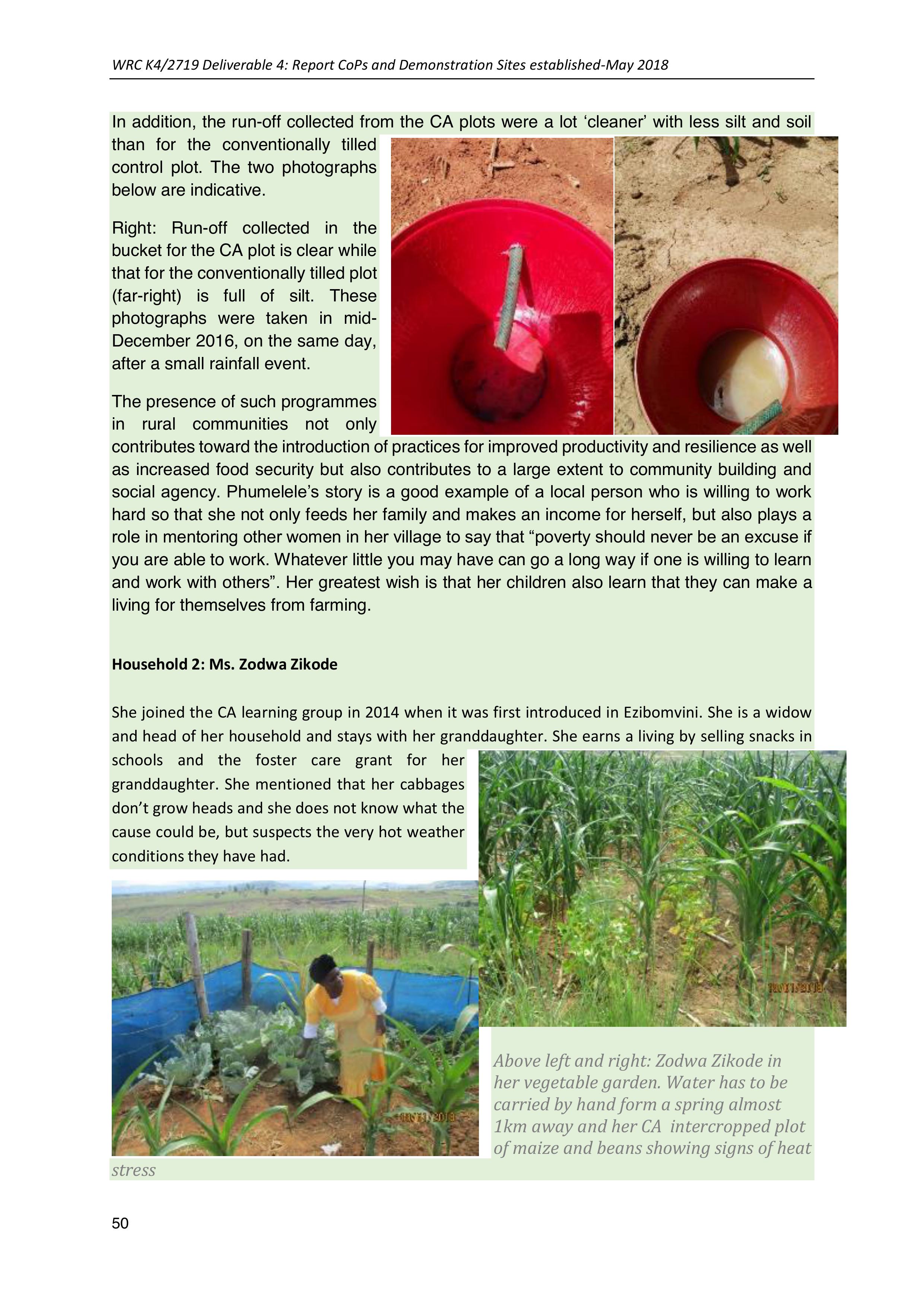

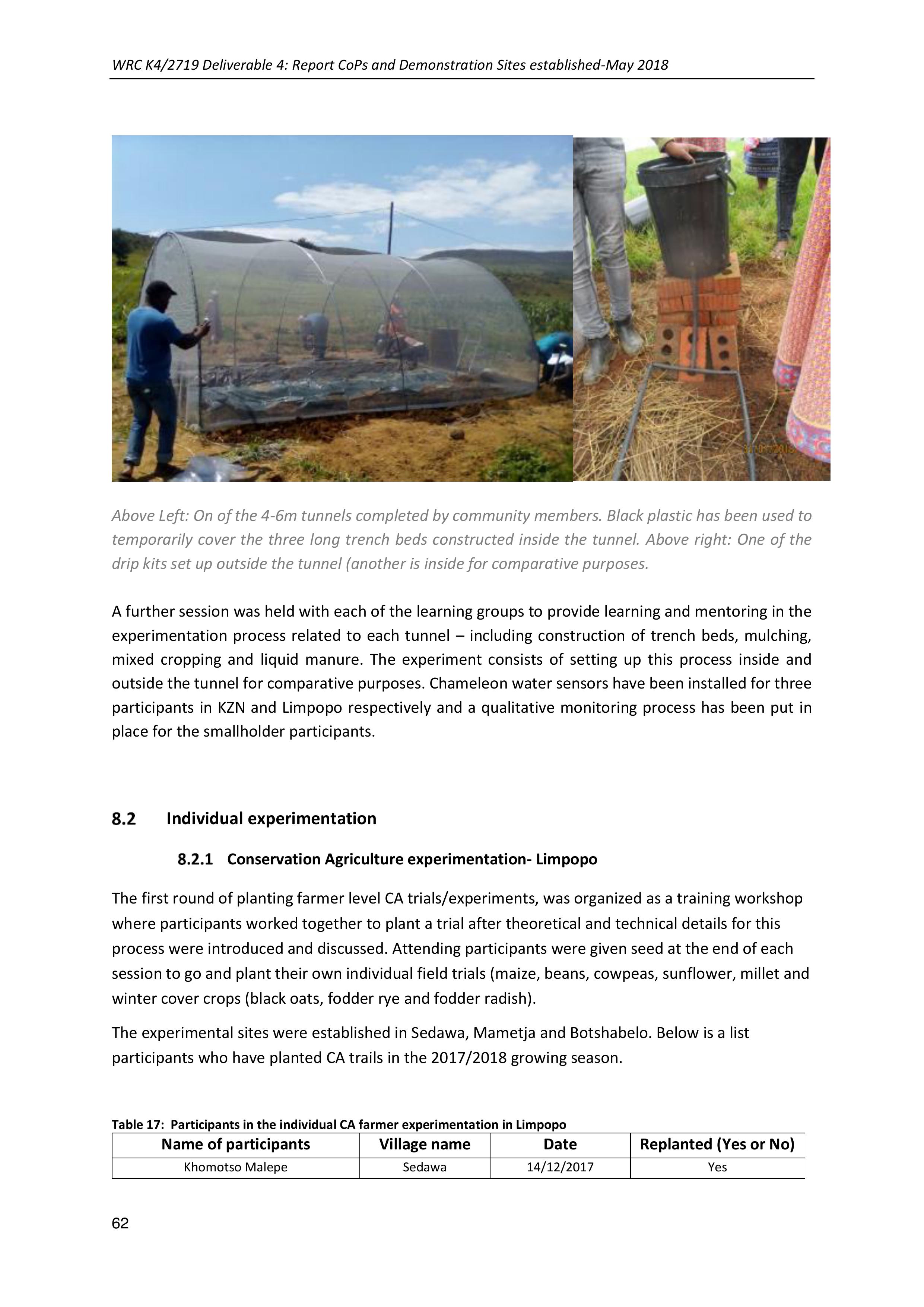

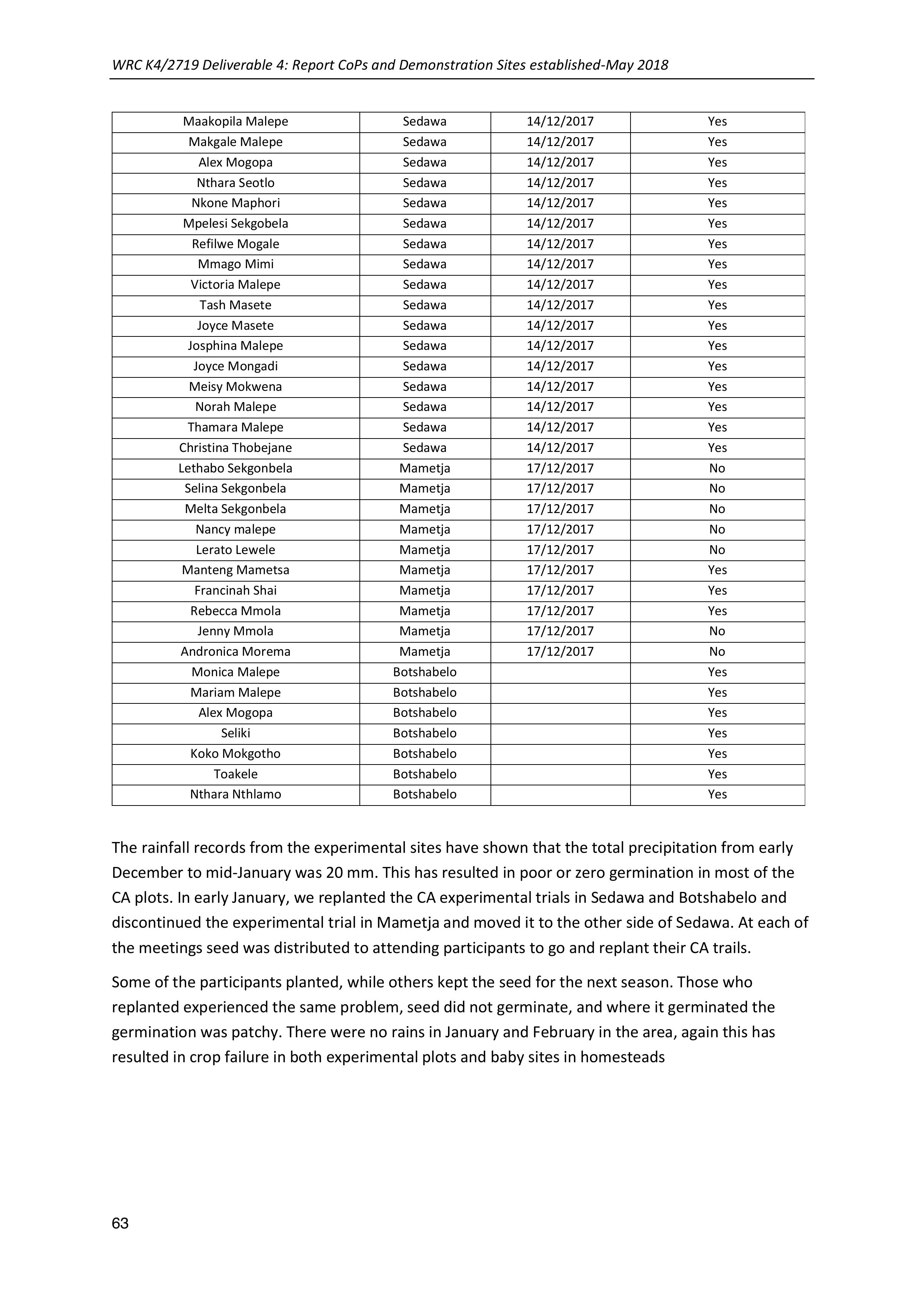

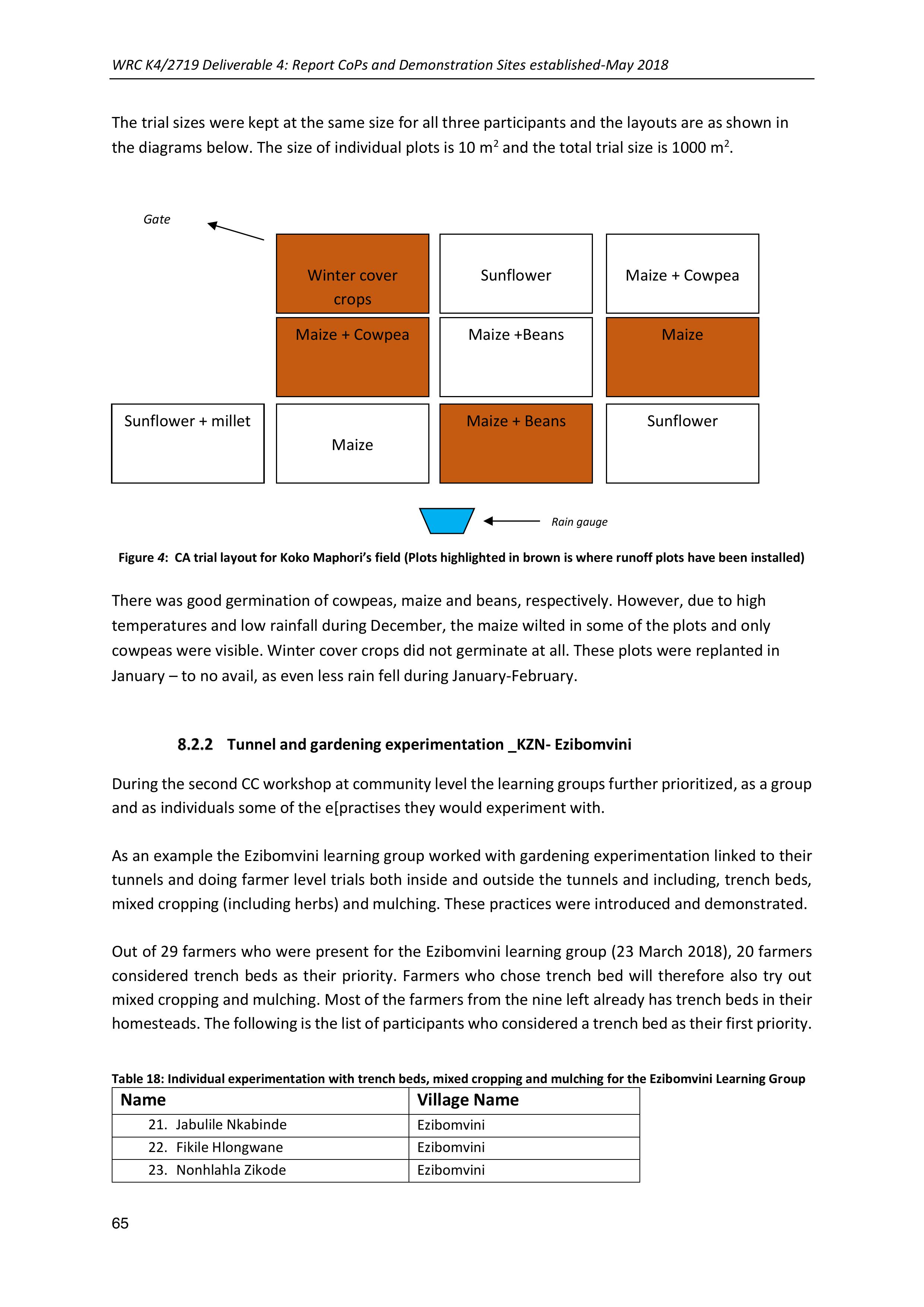

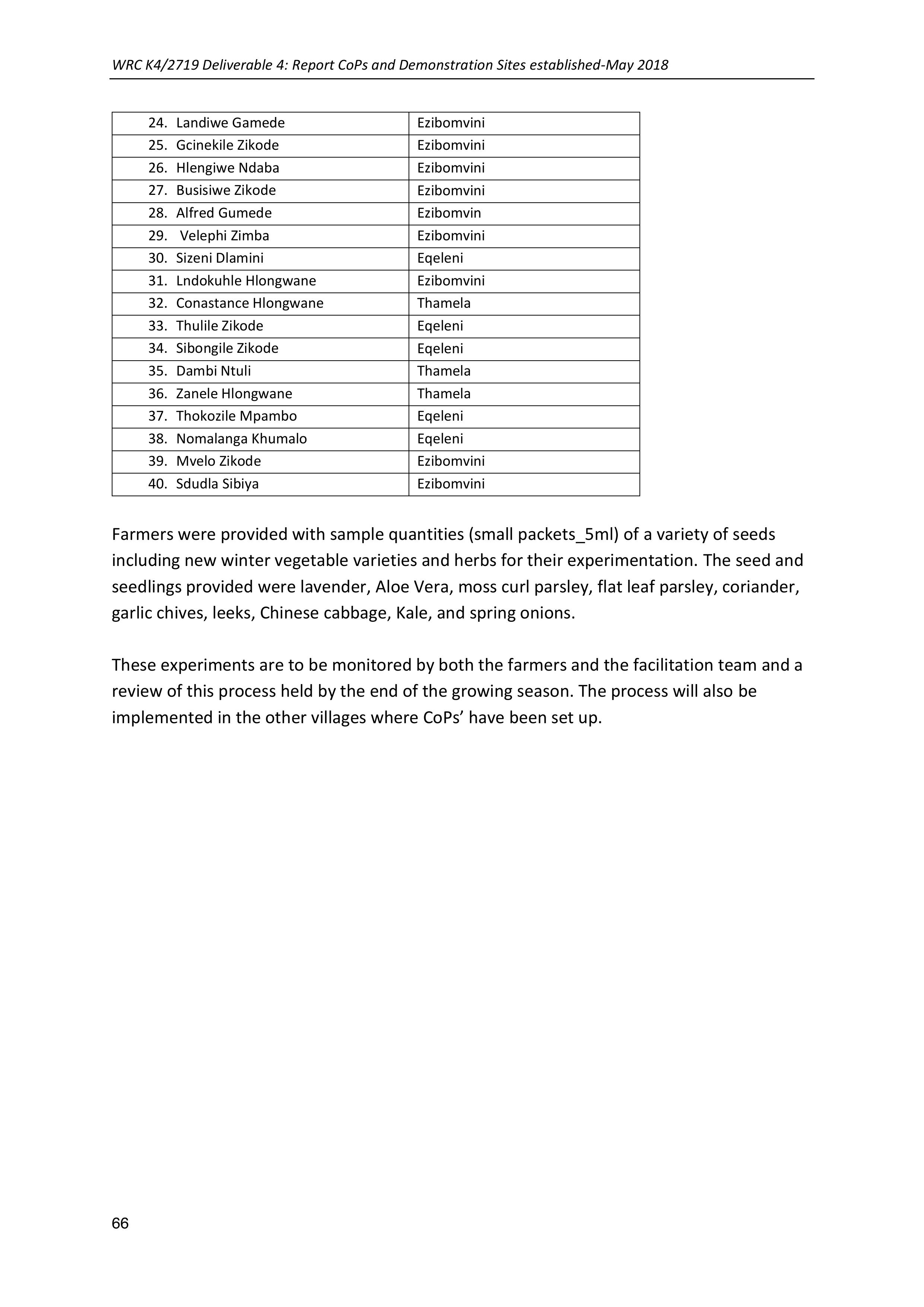

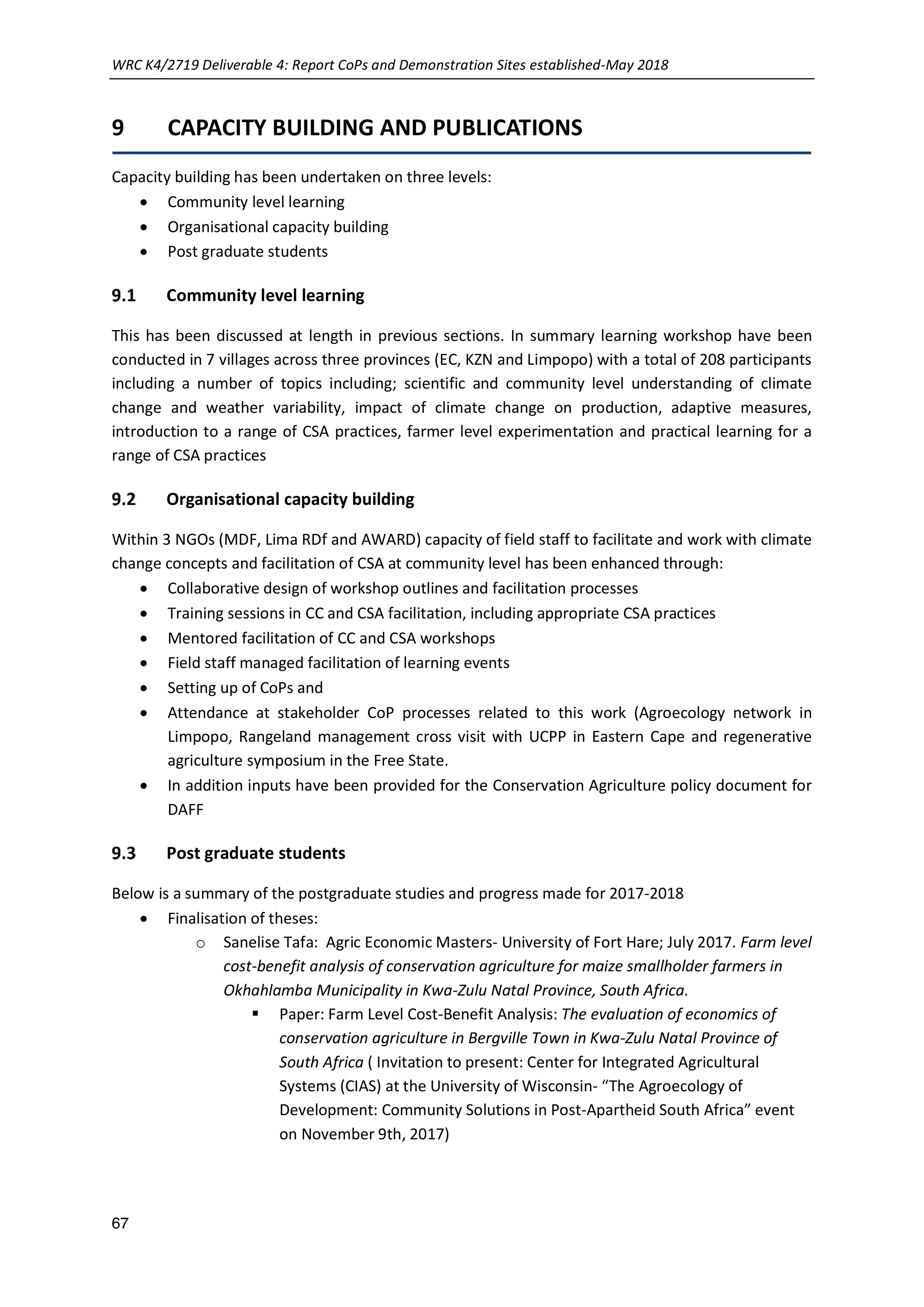

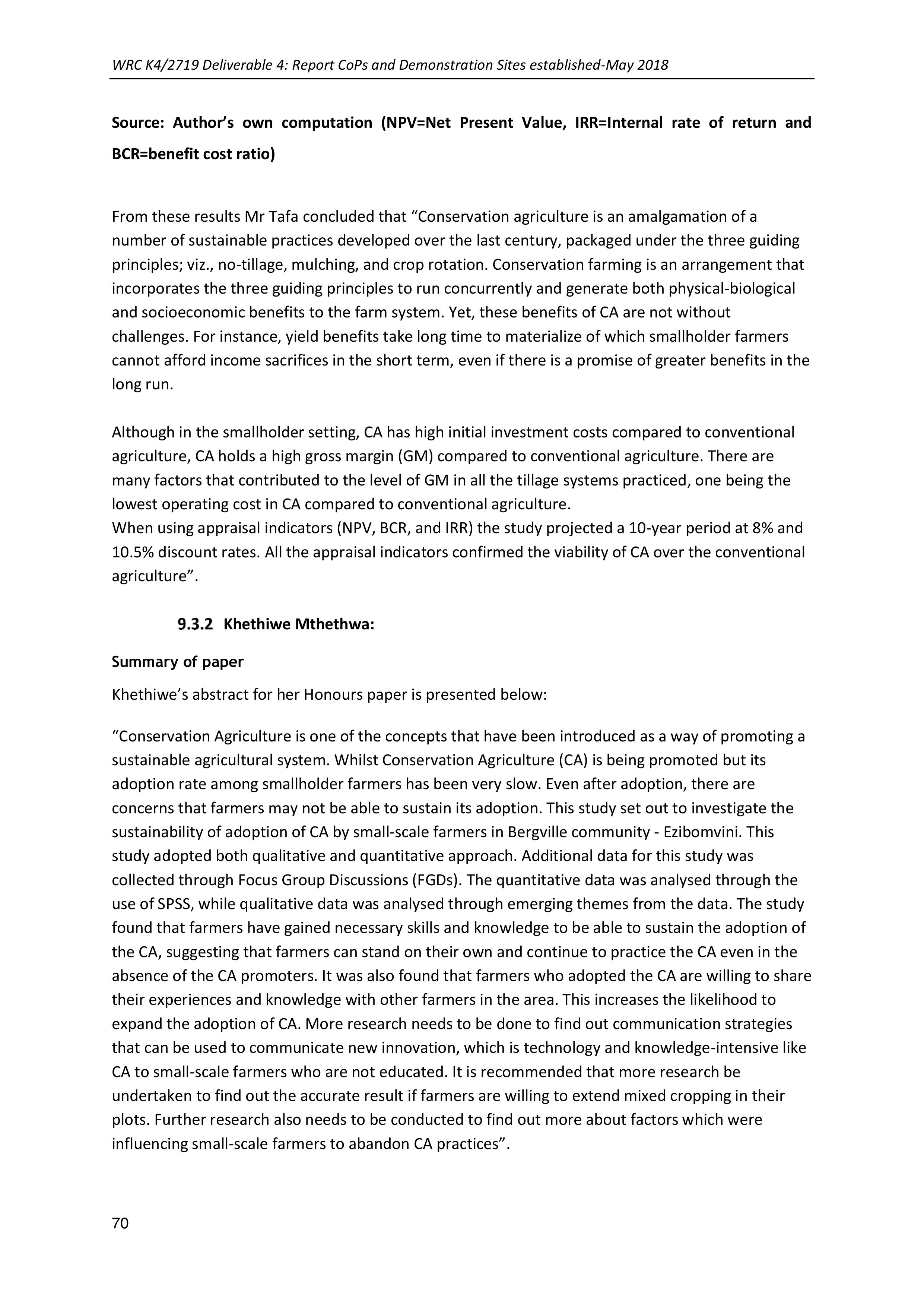

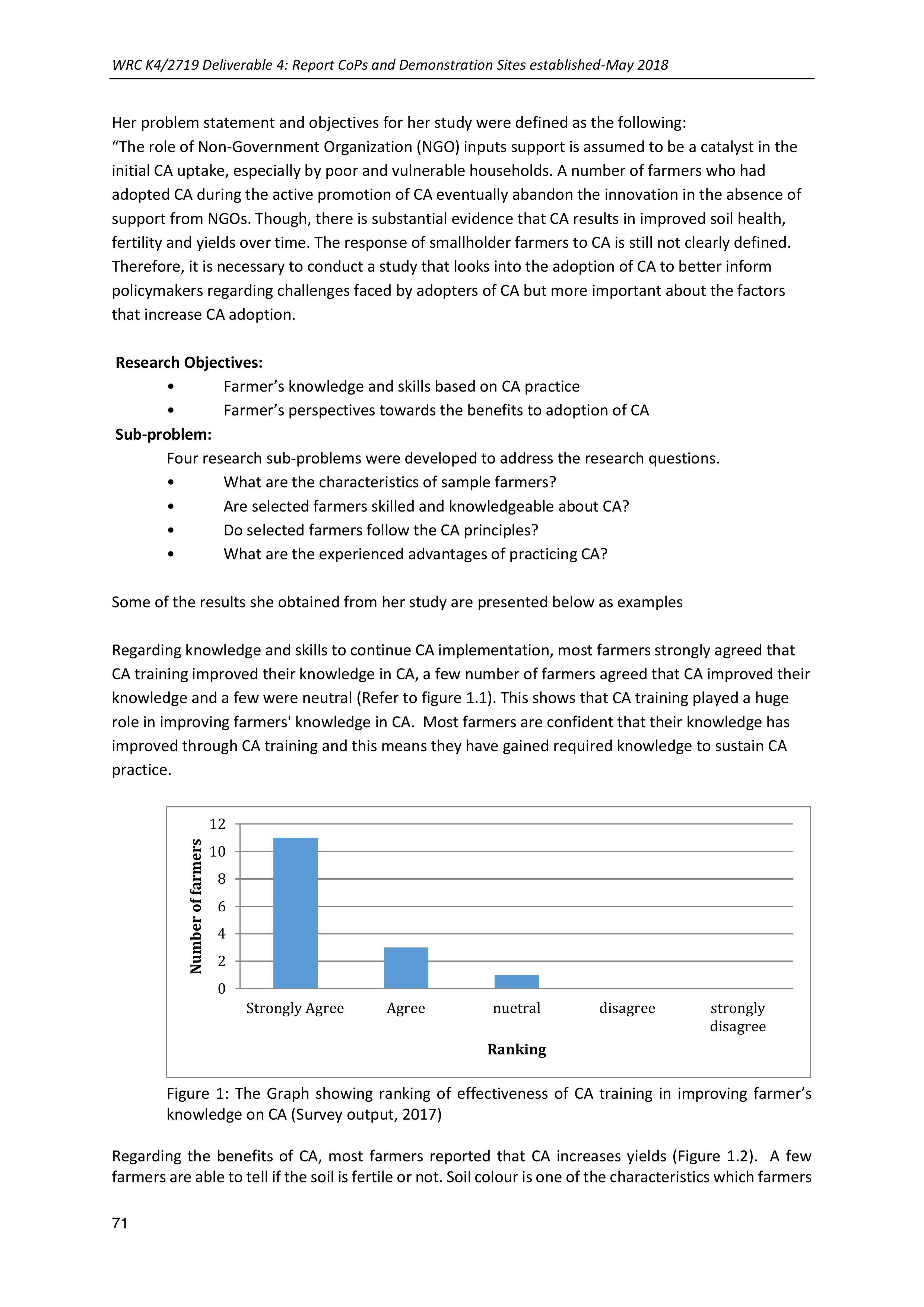

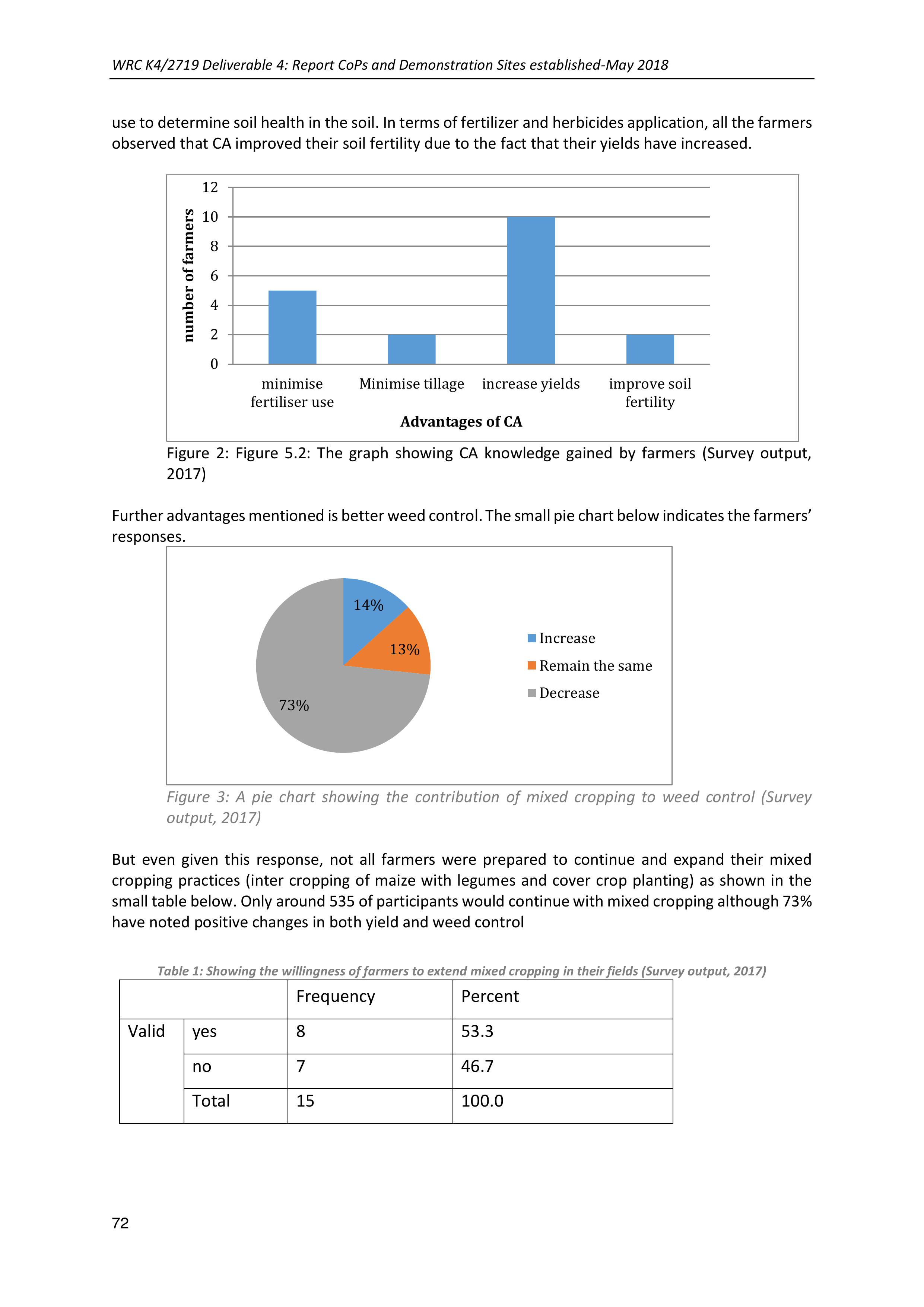

4