Sokhulu baseline: September 2024.

The seven villages in the Sokhulu community, including twenty households from each village,

participated in the study by completing face to face surveys in May 2024.UKZN undertook the

survey, using a questionnaire designed jointly between the UKZN and MDF teams. The data from

the seven villages is presented collectively as the Sokhulu community area.

1.1OVERVIEW

84% of households have lived in the area for more than 30 years with a very small percentage

93%) of people who lived there for less than 5 years. This indicates a stable community, despite

the inux of people into the area for work in the mining and forestry operations in the area.

Community members like living in the area for farming (51%), nature (28%), peace and ubuntu

(26%), the safety and lack of crime (12%), for rewood (11%), and for the sports in the area (8%).

The results show an emphasis on harvesting of natural resources for livelihoods in the northern

region and an emphasis on farming in Sokhulu.

The main development challenges mentioned were bad roads and poor infrastructure (60%),

lack of availability of water (43%), and inequality in the area in terms of distribution of benets

(22%). Poverty, the closure of the river mouth and the fencing of gardens were also raised as

issues. Community members also raised the need for business opportunities and skills

development, the provision of services, including water, electricity, schools and healthcare as

well as an improved internet network, the removal of mining companies and a reduction in the

planting of gumtrees, they require dip for livestock, need to reduce crime, and want the equal

distribution of RDP houses. Waste collection and poor waste management was raised as a

challenge in the area.

From the survey, households had an average income of less than R3000 - R4000 per month.

Given that most households are larger than average (Ave 7,8), the per capita income is low.

Based on money spent on food, most households in the region live below the food poverty line

and the general

poverty line.

However,

households

supplement their

food baskets

signicantly from

resources

collected from the

environment (land

and sea). The

picture alongside

indicates the high

reliance on shop

bought food in

Sokhulu (100%), followed by food produced locally (~70%), marine harvesting ((43%) and

school feeding schemes (40%).

76% of household members are aware of climate change, referring to extreme weather

conditions (27%), uctuation in weather patterns (24%), temperature and heat increases (6%),

thunderstorms being much worse than before (5%), and ooding (5%). It is evident in Sokhulu

that the main impacts of climate change are felt in relation to loss offarming potential, through

land and elds damaged by oods, variable rainfall and droughts and the loss of trees, which is

a valuable natural resource, through storms. Other points raised by communities are the

reduction in shade due to loss of trees, loss of life in extreme weather events, roads are

aected, livestock is damaged, and there is no longer enough grass for grazing.

The Sokhulu community is currently not acting proactively to manage climate change

specically (64%), as they lack knowledge about how to deal with climate change (8%). Some

respondents said that they try to plant more trees and conserve nature (7%), they avoid building

next to rivers (3%) and some have stopped farming on their elds (2%), as an adaptation to

climate change. They did not identify deliberate actions being taken by households to increase

agricultural resilience to climate change. Certain practices, including the use of manure as an

organic fertiliser and the selection of crop species suited to local temperature and rainfall

conditions, have been widely implemented. These are not new practices, and have been

adopted to reduce input costs, crop mortality, and enhance yield per unit eort. Communities

have therefore been responding to changing environmental conditions over time. However,

given their awareness of climate change and its impacts, it is evident that knowledge

development and tried and tested practices in response to climate change require attention in

the Sokhulu area.

Community members believe it is important to protect the environment as it gives life (36%), for

future generations and sustainability (20%), it provides food (18%), it provides shade (9%) and

clean air (9%). Respondents stated that because Richards Bay Minerals cuts trees and pollutes

the air, it is very important for them to protect nature to counter this impact.

Respondents reported the following ecosystem goods and services:

•shing and harvesting of mussels (15%)

•wood for building houses and kraals (20%)

•grass for roong and reeds for weaving (5%)

•trees for rewood (36%)

•food (vegetablesand fruits) (13%)

•medicinal purposes and cleansing (26%)

•shade from trees (10%)

The environment supports livelihoods in Sokhulu withthe environmental wage being valuable to

between 20% and 36% of households in dierent ways, which is signicant.

1.2SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASPECTS

In the baselines survey undertaken, 20 households were interviewed in May 2024 in the

following seven villages: eHlawini, eHlanzeni, kwaNtongonya, Ethukwini, eMalaleni,

kwaManzanyama and kwaHolinyoka.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Male and female headed households are reasonably evenly balanced at 49% and 53%

respectively. This is somewhat higher than the national average for 2022 of 45,7% female

headed households in rural KZN. (StatsSA, 2022).

The average household size for the village is 7,8, compared to the national average of 3.4,with

households ranging from between 3-25 individuals. The dependency ratio for these households

is extremely high.

In terms of age, the population in Sokhulu is skewed signicantly towards the age group of

0-18 years.

Age group in years

StasSA %

Sokhulu %

0 -18

28,8

45

19-34

35,1

30

35-59

27,1

20

>60

9

5

The large proportion of children under the age of 18 years in this area is likely a combination of

the community being well settled in the region (little in or out migration) as well as access to

services such as healthcare and schools (specically high schools). This diers signicantly

from the northern villages inside the IWP, where the proportion of children under 18 years is

much lower.

1.3INCOMES AND LIVELIHOODS

Of the 140 households interviewed 138 households (95%) fall below the national poverty

line (R1558/month/capita income). This is because the households have on average 7,8

members and are quite large. This number is skewed by a small percentage of very large

households as reported by respondents. If this is taken into account, then around 66% of

households fall below the poverty line. This is more reasonable when compared with other data,

showing quite a high degree comparatively, of formal employment in the region as well as small

businesses and self-employment.

Income range in Rands

No

Percentage

Cumulative percentage

0-1000

3

2,2

2,2

1001-2000

29

21,0

23,2

2001-3000

29

21,0

44,2

3001-4000

23

16,7

60,9

4001-5000

4

2,9

63,8

5001-6000

9

6,5

70,3

6001-7000

7

5,1

75,4

7001-8000

1

0,7

76,1

8001-9000

4

2,9

79,0

9001-10000

6

4,3

83,3

>10 000

23

16,7

100,0

Total

138

98,6

100,0

The following income categories were mentioned by the participants – own business and small

businesses were considered dierent categories. Own business included farming, forestry

taxis, transport and similar businesses while small businesses were more along the lines of

spazas, resale of clothes and meat and similar activities. A proportion of the community makes

a reasonably substantial income from both farming and forestry (contracted to SAPPI).

Income categories

No of hh (n= 140)

No of individuals

% individuals

Formal employment

31

40

6%

Contract workers

56

56

9%

Own business

28

28

5%

Small business

30

32

5%

Social grants

132

313

94%

Unemployed

124

318

51%

The unemployment rate is very high in this area, indicating that around 88% of households have

unemployed adults living there and 51% of working age adults are unemployed. Levels of

unemployment are much higher than the national average of 32,9% (StatsSA,2024).

Reliance on social grants (pensions and child grants) as an income source is very high, with 94%

of households receiving grants. A number of households mentioned that they receive

remittances from family members who do not live in the area.

Food shortages are common, with 93% of households mentioning that they experience a

shortage of food. Shortages are experienced for some households during winter (40%),

summer (67%) and throughout the year for 9% of households.

1.4AGRICULTURE

Agriculture in the form of cropping and livestock husbandry is extensively practiced across

Sokhulu, albeit at dierent scales. Around 71% of households undertake cropping in gardens

(more intensive with some irrigation) and dryland elds which are largely in the ood plain.

Access to elds in the roughly 400ha of cropping elds on the ood plain is open to all 7 villages,

and access is generational, with a growing rental market as all land has been claimed over the

years, but notall families use their allocations on an ongoing basis.

The table below summarises the extent of agricultural activities in Sokhulu

Table 1: Extent of agricultural activities across Sokhulu, May2024 (n=140)

Activity

% of HH

Units

Comments

Gardens

68% (31% male,

37% female)

100m2-

1000m2

gardens are either quite small and at homestead level or

further away in wetland areas or the ood plain

Fields (ood

plain)

22% (9% male,

13% female)

1ha plots

Fields are in 1ha portions, where farmer mostly have

between 1 and 3 elds.

Fruit

production

19%

1-4 trees per

household

and ~20-100

at eld level.

Trees include oranges, naartjies and bananas – grown at

scale in the ood plain and trees such as avocadoes,

mangoes and lemons planted more frequently at

household level.

Poultry

35%

Ave 14

chickens

Poultry consists of traditional chickens which roam freely

as well as small production units of broilers. Keeping of

layers is not common.

Goats

25%

Ave 12 goats

Goats roam freely, some homesteads have kraals but not

all

Livestock

25%

Ave 10 cattle

(2-50)

Cattle roam freely. Herders are employed. There is conict

in the community from cattle invasion into elds and

gardens.

Crops commonly grown in the area are shown in the table below in decreasing percentages.

Interestingly participants who indicated ‘none’ as their crops, are those whose elds have been

inundated due to the back ooding from the closure of the mouth some eight years ago. This

gives an estimation of the lost elds as being around 23% of the total area. Sweet potatoes,

amadumbe and cabbages are the most common crops grown. In the dryland elds (on the ood

plain) the most common crops grown are

sugar cane, sweet potatoes, amadumbe,

beans,

maize and bananas. It is clear form the

crop choices that farmers in the area

have adapted to cropping in these

wetland conditions with cyclical ooding

and water logging. Crops such as

amadumbe and bananas are planted in

the wetter areas of the elds and can

withstand high levels of water logging.

Irrigated crops consist of the vegetables

such as cabbages, spinach, onions,

lettuce, carrots, beetroot and tomatoes.

Below are a few indicative pictures of farming in the oodplain

Figure 1: Above left: A typical dryland eld in the ood plain planted to sugarcane and bordered with bananas and

Above right: Smaller fenced garden in the lower lying areas, close to sources of water producing crops such as sweet

potatoes, beans, cabbages and onions.

Add pics and examples

CROP

Percentage of respondents

Sseet potatoes

50

cabbage

43

amadumbe

39

spinach

30

onion

27

lettuce

22

None

23

potatoes

19

maize

18

green pepper

14

carrot

14

beetroot

14

tomatoes

12

oranges

10

naartjies

8

sugar cane

8

banana

6

1.5INFRASTRUCTURE

Uncontrolled development and haphazard management of small-scale gum plantations in the

area and these in addition to climate change impactshave led to a drastic decrease in in the

groundwater as well as wetland areas (around 36% reduction) in the last decade.These issues

combined with the RBM mining

and dunes, which has changed

the water ow and

management of the entire area

has had the outcome of

inundation of lower lying areas

leaving some homesteads and

elds under water, with a

drying out of the higher lying

areas with too little access to

water and drying out of

boreholes there.

Figure 2: A typical view of the poorer homesteads in the area. People have come into the area from as far as Manguzi

due to the work opportunities provided through the mines and the timber industry.

Figure 3: A view of a typical homestead in Sokhulu surrounded by a patchwork of gum plantations. In the foreground a

small swamp has formed close to the homestead, a trend that has increased in recent years, thought to be due at

least in part to the huge RBM dunes channelling water into this area both underground and as runo from the dunes.

The ’hill’ in the background is a large, rehabilitated mining dune.

Given that the communities in Sokhulu have access to livelihoods options such as small scale

forestry, eld cropping and livestock, which has provided for a reasonable and in some cases

substantial income for a proportion of the households and that these communities have

ongoing development support (however badly managed) through RBM, the Umfolozi LM and the

Department of Agriculture, the overall situation in terms of livelihoods and poverty here diers

somewhat from villages inside the IMPA. Basic service provision through roads, electricity and

sanitation is more evident in thearea.

The graph below summarises infrastructural considerations in Sokhulu.

As shown in the types of services graph below the following further dierentiation in service

provision can be made:

•Although access to electricity it available to the whole of Sokhulu (97%), use is limited

to around 84% of the community. Use of rewood for both cooking and light is equally

common (88%) and community members also use gas (21%) and parain (7%) for

appliances such as fridges and stoves. Firewood is cut locally from the numerous

plantations surrounding the homesteads and natural bush and forests.

•Water access of 35% at household level relates to access to taps in household yards

(22%) and 10% of households having JoJo tanks for rainwater harvesting. The 63%

without access to water at household level are likely to have some access through

communal standpipes or having to rely on water provision through Municipal water

tankers. In community meetings held the issue of lack of access to water was raised as

an immediate and important concern. It appears that some small borehole dependent

water schemes reticulated to communal standpipes have run dry and that provision of

water by the municipality in these cases has been very intermittent.

•Toilet access of 97% relates pit latrines, either supplied through the municipality,

development projects or home built. Only 3% of households have access to waterborne

sewage – the assumption here is that these household have their own septic tanks, as

there is no sewage network or treatment in the region.

•With respect to housing, 29% of households have had support from government in the

form of RDP houses. This signies a large state intervention in housing support for the

Sokhulu community as this percentage of support is considered substantial when

compared to other rural communities both in the region and in rural areas of KZN more

generally.

•There is no municipal solid water collection process in Sokhulu.

•Cell phone reception in the area is limited with only 34% of community members being

bale to access networks such as Vodacom and MTN.

•With respect to roads, 59% of respondents mentioned that access is provided by gravel

roads and the other 41% responded that there were no roads. Away from the long

stretch of unpaved road providing access into Sokhulu (which is not in a good

condition), the smaller tracks in and around villages have been made by locals for

Electricity

Water in

household

or yard

Toilets RDP

Houses

Waste

collection

Network

connection Roads

Available 97 35 97 29034 56

Not available363 367 98 66 41

0

20

40

60

80

100

Percentage

Access to services

access to surrounding bush and plantations as well as the oodplain. These tracks

haven’t been oicially graded but are rough approximations of roads made through use.

Due to the sandy nature of the region, these can quickly become impassable when

used by heavy vehicles such as tractors with trailers and also whenwet.

The access to services is also reected in the development needs and priorities mentioned by

respondents, as shown in the graph below.

Respondents focused on the need for reliable access to drinking water, job opportunities,

roads, education and opening of the river mouth. A thread passing through all these requests is

the need for equity in provision of services.

1.6SOCIAL ORGANISATION

The proportion of respondents who belong to social groups/organisations is limited to 38%. Of

these the following groups are active in these villages:

33%

Burial societies

72%

Stokvels

21%

Church groups

Eskomtank TapPit

toilets

water

toilets

Govern

ment

self

built All Vodaco

mMtn gravel

Electricity WaterToiletsHouseNetworkRoads

Series1 9710 22 94329 49 17 11 59

0

20

40

60

80

100

Percentage

Types of services

7

60 43

12 715 22

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Percentage

Main development challenges

5%

Women’s groups

Similar to other rural areas, the larger proportion of women belong to these groups and us these

social organisations to provide economic and social safety nets for themselves and their

families.

Both the Local Municipality and the Traditional Councils (TCs) are important in Sokhulu for

access to services and development and conduct meetings in the community which are

reportedly well attended. Development and farming committees are linked to the TCs. Despite

strongparticipation and reliance on these institutions only around 43-56% of respondents felt

that they could trust these institutions. A typical explanation from these community members

revolves around the need of the community to be involved in decision-making, equity across

villages and community members in terms of benet from services and projects and the need

for these leaders to provide feedback and information to community members.

1.7NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Human intervention has substantially impacted on the ecosystems of this ood plain, primarily

through vast expanses of gum plantations (commercial forestry commenced here around 1933),

sugar cane (started around 1959) and dune mining (RBM started these operations in 2004), the

longer-term impacts of which are now becoming evident through both a substantial reduction in

the groundwater and water quality issues in the area and the consequences of channelisation

of the local rivers – the latter which has also impacted heavily on coastal and mangrove

ecosystems and the loss of wetlands.

The Sokhulu traditional council area is based at the southern tip of the Isimangaliso Wetland

Park, with only the previous eMapelani Reserve area incorporated into the reserve itself, a point

that is seemingly not well understood by either the TC or the community members. This area is

further north towards the coast with the conuence of the St Lucia estuary and the Umfolozi

and Umsunduze rivers and is not populated, as people were removed from there when the

Wetland Park was formed in the late 90s’. The Sokhulu villages/isigodi that abut on this area are

Ehlanzeni and Ehluwini, where the Sokhulu Traditional Council oice is housed.

In the past, prior to the establishment of the IWPA, tourism activities created some income for

the broader community. The eMapelani Reserve area is one of the 14 odd land claims that have

been lodged against the park. At the same time, the Sokhulu community trust is beneting from

an annual payment from the reserve. Funds from this payment is meant to support the fenced

communal crop lands (roughly ~200ha) on the oodplain, supporting with tractors for

ploughing, input subsidies and transport of produce from the plain to collection points in the

villages higher up. Presently this committee is under review for misuse of these funds.

Community members have an understanding of their impact on the environment, with close to

90% of respondents feelingthat it is important to protect the environment. All community

members use local resources for grazing of livestock, harvesting reeds and medicinal plants,

harvesting wood (building and rewood) as well as marine resources (shing and coastal

harvesting), mainly for food. As mentioned agricultural production is common in the area.

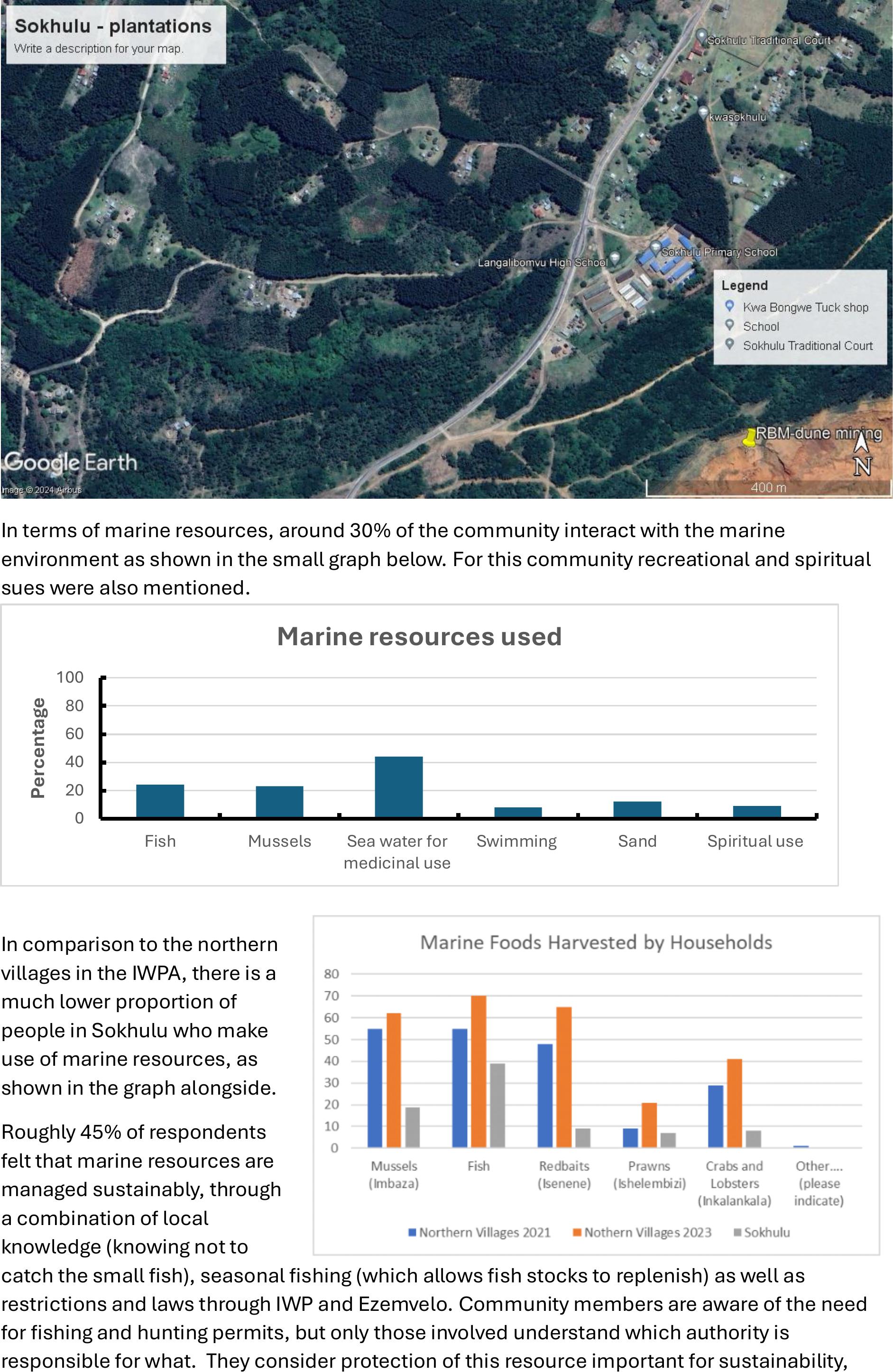

The largest land use, which covers the vast majority of the area is gum plantations, as shown in

the google earth snapshot of eHlanzeni and the tribal court below, as an example. There are

small cleared areas around homesteads, but the vast majority of the land is covered by

plantations, natural forest/bush patches and small localised bogs and wetlands.

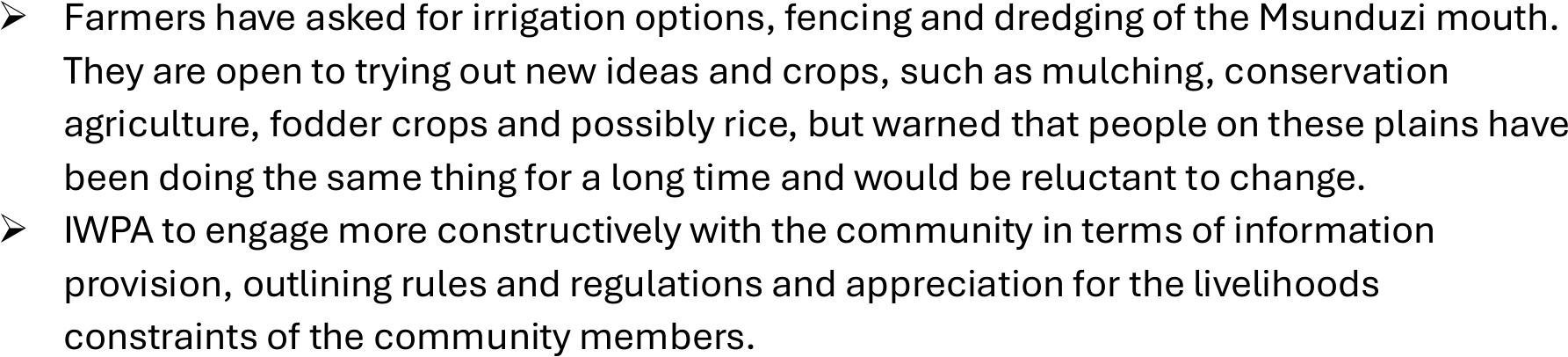

In terms of marine resources, around 30% of the community interact with the marine

environment as shown in the small graph below. For this community recreational and spiritual

sues were also mentioned.

In comparison to the northern

villages in the IWPA, there is a

much lower proportion of

people in Sokhulu who make

use of marine resources, as

shown in the graph alongside.

Roughly 45% of respondents

felt that marine resources are

managed sustainably, through

a combination of local

knowledge (knowing not to

catch the small sh), seasonal shing (which allows sh stocks toreplenish) as well as

restrictions and laws through IWP and Ezemvelo.Community members are aware of the need

for shing and hunting permits, but only those involved understand which authority is

responsible for what. They consider protection of this resource important for sustainability,

0

20

40

60

80

100

FishMusselsSea water for

medicinal use

SwimmingSandSpiritual use

Percentage

Marine resources used

livelihoods and future generations. Mention was made of changes in the marine environment

which included depletion of sh stock due to changes in climate and also due to there being too

many shers. They also mentioned that the mangroves have reduced a lot and what was left has

died back in the last eight years due to the closure of the rive mouth. This has reduced their

function of managing water levels in the lower lying areas as well as reducing the marine

resources such as crabs and certain sh.

In Sokhulu, the villages engage less with IWPA, with only 8% of households obtaining contract

work through IWP management activities, 3% obtaining access to bursaries, 4% stating that

they get support for their gardens, and 70% stating there are no benets. The table below

outlines what community members know about the IWPA.

There is a reasonably large number of community members who believe the IWPA closed the

river mouth (35%). Others believe it was done by Richards Bay Minerals (RBM). In general, there

is an inherent understanding of the cyclical nature ofthe wetland system and the impact of

channelisation on the system. For most community members, but specically the farmer on the

oodplain this is understood as a positive intervention.

1.8RECOMMENDATIONS

➢Working with village-based groups of farmers to explore adaptive measures and

climate resilient agriculture practices and to set up a process of experimentation with

dierent options and ideas to improve the management of water and soil on the

oodplain as well as at the homesteads or the smaller communal gardens.

➢Taking some soil and water samples across the ood plain to ascertain the fertility and

quality of the water (there is suspicion among community members of poisoning of the

water through the RBM mining operations).

➢Comparison of conditions on the oodplain in winter and summer, as well as further

discussions with key informants about channels, patches of natural vegetation, ood

control and scenarios for management. This will need input from agricultural engineers

and hydrologists, as well as some form of mapping.

➢Engagement with the community for awareness raising and information provision

around the functioning of the system, the impacts of closure and opening/dredging of

the river mouth and the impact of dierent land use practices, to better inform more

sustainable landuse practices.

➢Continuation of liaison between MDF and the Wildtrust restoration team to allow for

village-based clearing of unwanted gum plantations and recovering theseareas as

productive land, through agroforestry systems.

Protect our

coast

Protect our

nature

Don’t

know

It closed

the river

mouth

Same as

Wildlife

Hire

people No fishingEmpty

promises

Series1 813 21 35 610 5 5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Percentage

What do you know about IWP

➢Farmers have asked for irrigation options, fencing and dredging of the Msunduzi mouth.

They are open to trying out new ideas and crops, such as mulching, conservation

agriculture, fodder crops and possibly rice, but warned that people on these plains have

been doing the same thing for a long time and would be reluctant to change.

➢IWPA to engage more constructively with the community in terms of information

provision, outlining rules and regulations and appreciation for the livelihoods

constraints ofthe community members.