1

Progress Report

Version: September2022

Grant code

Project Title

Isimangaliso EbA

Grantee

Wildlands Conservation Trust

Subgrantees

Mahlathini Development Foundation

Project Start Date

01/08/2023

Project End Date

31/07/2027

Reporting Period1

01/07/2024- 10/12/2024

Project Country(ies)

South Africa

Project Cost

Total & percentage

Blue Action Fund Contribution

EUR 146 668

Match Funding

Not applicable

Report Compiled By

Erna Kruger

Date of Submission

10thDecember 2024

Regular reporting is essential for Blue Action Fund to monitor the progress of the projects it

funds. Each project reports biannually through the workplan in conjunction with the funding

advance request as well as the progress report. In addition, only on an annual basisthe

progress report should be accompanied by Annexes A- F. Theses progressreports are

needed to:

•Monitor project progress

•Analyse the overall programme of Blue Action Fund

•Collect information/data to allow Blue Action to report to its own donors

•Communicate project’s impacts and highlights to donors and other stakeholders

•Draw lessons learned and compile these for knowledge exchange on marine

conservationand sustainable livelihoods

•Serve as the basis for a progress call between Blue Action and the grantee

1This should be a six-month period. With the exception ofthe informationprovided in the annexes (which are

only submitted on an annual basis) allcontents ofthe progress report should refer to accomplishments and

developments of the last work period only, i.e. the last sixmonths.

If you are submitting this progress report withthe annexes constituting the annual report, please indicate the

annual period dates in the annexes.

In case of an annual report, the narrative part corresponding to the first six months of the year is to be found in

the progress report for that period.

2

1)

Progress report summary

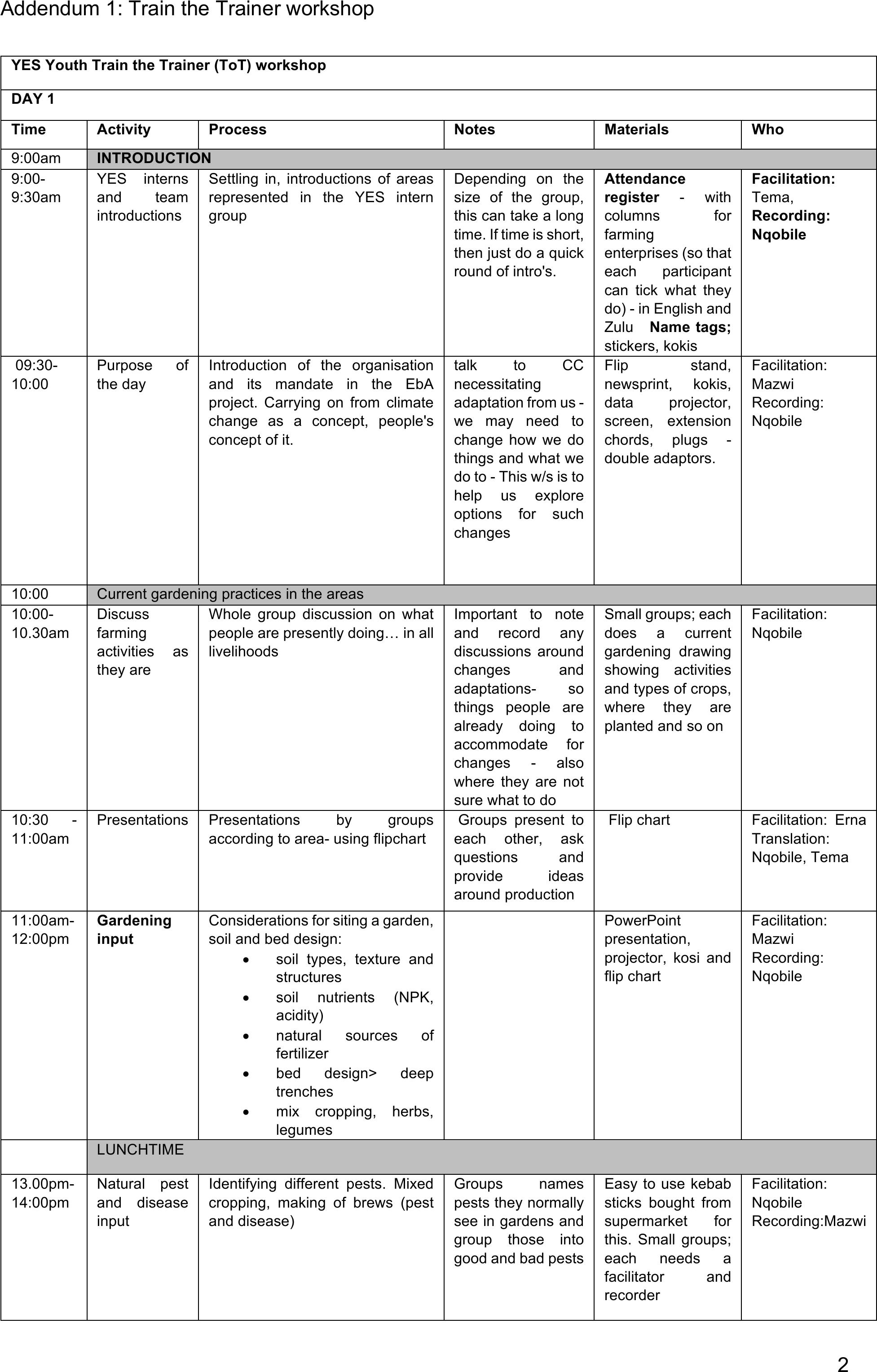

Below is a summary of activities to be undertaken by MDF (as per the FAR and workplan)

‘Activity 5.4.1

Intensive small-scale farmer training and support. Homestead.Provide intensive small-

scale farmer training and support

Deliverable 5.4.1.a

40-60 small-scale farmers trained and supported (MOV: training/attendance registers).

Deliverable 5.4.1.b

1 x 2.5-day CCA workshop and 5x training days per hub - Intensive regenerative agriculture

training and mentorship workshops held at the homesteads and at the Community Resource

Hubs at the beginning of each site intervention: 1 in year 2, 2 in year 3 and 1 in year 4. (MOV:

workshop registers, photographic evidence, course outline). Twenty-five participants each.

Deliverable 5.4.1.c

15 farmers per site supported with intensive production and water management

infrastructure and support. (MOV: photographic evidence)

Activity 5.4.2

Train the trainer: WILDTRUST Hub staff will be incorporated into all initiation activities to

ensure they are able to maintain the hub demonstration gardens, provide additional support

to community members in between Mathathini staff visits, and provide basic practical

demonstrations off CCA gardening to community members visiting the hubs.

Deliverable 5.4.2.a

Four (4) hub teams trained and mentored to be future CCA mentors (MOV: training registers,

course outline).

Deliverable 5.4.2.b

Four (4) climate-smart demonstration gardens established, one (1) at each hub site,

maintained by Hub staff (MOV: photographic evidence).

Activity 5.4.4

Climate-smart agriculture technique demonstrations.YESyouth employed by WILDTRUST,

that are trained as trainers by sub-grantee Mahlathini, train an additional 200+ community

members in mini-demonstrations of climate-smart agriculture techniques during the project.

4 demonstration days per hub x 5 in total, 50 people at each demonstration

Deliverable 5.4.4

Two hundred and fifty community members trained by YES team in climate-smart agriculture

techniques (MOV: Attendance registers)

Activity 5.4.5

Facilities to support climate-smart agriculture. Establish facilities to support climate-smart

agriculture

Deliverable 5.4.5

Five (5) communal boreholes established at 5 primary community areas for garden support

and drinking, and seed tunnels and seedling provision support at each community Hub (MOV:

photographic evidence).

1

2Activity Not Yet Due; Activity Started -ahead of schedule; Activity started – progress on track; Activity started but progress delayed; Activity start is delayed.

3Implementation progress on a cumulative basis as of the date of the report.

Project Subcomponents

Status2

Implementation

progress3(%)

Component 1:Coastal ecosystems, which are particularly relevant for climate change adaptation, are better protected and managed in a moresustainable way

Sub-Component 1.3: Funding for measures to reduce pressure and land-based stressors on coastal and marine ecosystems (in and outside protected areas)

Activity5.4.1 Intensive small-scale farmer training and support.

Activity

Started -

ahead of

schedule

60%

- Baseline surveys conducted and finalised – all 4 communities (Nkovukeni, kwaDapha, Mabibi, Sokhulu)– including vulnerability

assessments and identification of households

- 4x2,5dayCCA workshops done(Mabibi,kwaDapha,Nkovukeni, Sokhulu)

- 3 agriculture training daysat hubs (staff and interns)- towers, tunnels, field crops

- 3 training days at the communitylevel (Mabibi, Nkovukeni), 2 training days at kwaDapha

Seeds and seedlings to farmer (number!!

-14farmers in Nkovukeni, ?? farmers at Mabibiand ?? farmers at kwaDaphasupported withtrench beds and tunnels, 30 farmers with

tower gardens

-4 x 2,5 CCA workshops with community members (kwaDapha, Sokhulu, Mabibi,

Nkovukeni)?? no of participants

- 3 x climate resilient agriculturetrainingday athubs (Mabibi, kwaDahpa,

Mabibi)

- 8 x training daysin total atkwaDapha, Mabibi and Nkovukeni

-?? farmers supported with materials (tower gardens, trench beds, tunnels) and

??? farmers supported with seed and seedlings

Activity 5.4.2 Train the trainer.

Activity

Started -

progress

on track

45%

-ToTworkshop with YES youth and hubstaff at Nkovukeniand kwaDapha

-Establishment of demonstration gardens: one tunnel in KwaDapha hub along with tower garden, fenced off trench and tower garden

in Nkovukeni, awaiting finalization of demo site in Mabibi

-2 ToT workshops in CCA with Hub staff

-2 demonstration gardens initiated (Nkovukeni, kwaDapah), still to be finalised

Activity5.4.4 Climate-smart agriculture technique demonstrations.

Activity

Not Yet

Due

0%

Yes youth support to communities

Not yet started

Activity5.4.5 Facilities to support climate-smart agriculture.

Activity

Not Yet

Due

0%

2

Wild Trust has sited these facilities but haven’t started

3

2)Narrative report (July-December2024)

2.1 Small scale farming training and support: Household and Hub

For each activity,please provide an update on progress during the past work period, including key

accomplishments, impacts, highlights, any delays and issues encountered, key milestones reached, lessons

learned, positive achievements, etc.

2.1.1 Main activities

BAF

number

Date

Description

Persons

Time

5.4.1a and b

2024/11/12

BAF itemised expenditure list, FAR and workplan(Oct 24)

2 days

2024/11/22, 24-25

BAF delegate, meet and greet online meeting. Followed by

dinner at Mvutshana and then a field visit to Nkovukeniand

a presentation on progress

Mazwi Dlamini

3 days

2024/11/03

Updated BAF itemised expenditure list. FAR and workplan

as queriedby WT(Oct24)

Mazwi Dlamini, Erna

Kruger

1 day

2024/12/09-10

Gender mainstreaming on the EbAproject workshop in

Durban

2 days

5.4.1a,b,c

2024/11/21 and

2024/11/26

Field cropping workshop (materials and inputsfor file

crops), Enkovuleni,Mabibi,

Mazwi Dlamini

Nqobile Mbokazi

2 days

4

2.1.2 Mapping and baseline surveys. Narrative reports:

The seven villages in the Sokhulu community, including twenty households from each village,

participated in the study by completing face to face surveys in May 2024.UKZN undertook the

survey, using a questionnaire designed jointly between the UKZN and MDF teams. The data

from the seven villages is presented collectively as the Sokhulu community area.

Overview

84% of households have lived in the area for more than 30 years with a very smallpercentage

93%) of people who lived there for less than 5 years. This indicates a stable community,

despite the influx of people into the area for work in the mining and forestry operations in the

area. Community members like living in the area for farming (51%), nature (28%), peace and

ubuntu (26%), the safety and lack of crime (12%), for firewood (11%), and for the sports in the

area (8%). The results show an emphasis on harvesting of natural resources for livelihoods in

the northern region and an emphasis on farming in Sokhulu.

The main development challenges mentioned were bad roads and poor infrastructure (60%),

lack of availability of water (43%), and inequality in the area in terms of distribution of benefits

(22%). Poverty, the closure of the river mouth and the fencing of gardens were also raised as

issues. Community members also raised the need for business opportunities and skills

development, the provision of services, including water, electricity, schools and healthcare as

well as an improved internet network, the removal of mining companies and a reduction in the

planting of gumtrees, they require dip for livestock, need to reduce crime, and want the equal

distribution of RDP houses. Waste collection and poor waste management was raised as a

challenge in the area.

From the survey, households had an average income of less than R3000 - R4000 per month.

Given that most households are largerthan average (Ave 7,8), the per capita income is low.

Based on money spent on food, most households in the region live below the food poverty

line and the

general poverty

line. However,

households

supplement their

food baskets

significantly from

resources

collected from the

environment (land

and sea). The

picture alongside

indicates the high

reliance on shop

bought food in

Sokhulu (100%),

followed by food

produced locally

(~70%), marine harvesting ((43%) and school feeding schemes (40%).

76% of household members are aware of climate change, referring to extreme weather

conditions (27%), fluctuation in weather patterns (24%), temperature and heat increases (6%),

thunderstorms being much worse than before (5%), and flooding (5%). It is evident in Sokhulu

that the main impacts of climate change are felt in relation to loss of farming potential, through

land and fields damaged by floods, variable rainfall and droughts and the loss of trees, which

is a valuable natural resource, through storms. Other points raised by communities are the

5

reduction in shade due to loss of trees, loss of life in extreme weather events, roads are

affected, livestock is damaged, and there is no longer enough grass for grazing.

The Sokhulu communityis currently not acting proactively to manage climate change

specifically (64%), as they lack knowledge about how to deal with climate change (8%). Some

respondents said that they try to plant more trees and conserve nature (7%), theyavoid

building next to rivers (3%) and some have stopped farming on their fields (2%), as an

adaptation to climate change. They did not identify deliberate actions being taken by

households to increase agricultural resilience to climate change. Certain practices, including

the use of manure as an organic fertiliser and the selection of crop species suited to local

temperature and rainfall conditions, have been widely implemented. These are not new

practices, and have been adopted to reduce input costs, crop mortality, and enhance yield per

unit effort. Communities have therefore been responding to changing environmental

conditions over time. However, given their awareness of climate change and its impacts, it is

evident that knowledge development and tried and tested practices in response to climate

change require attention in the Sokhulu area.

Community members believe it is important to protect the environment as it gives life (36%),

for future generations and sustainability (20%), it provides food (18%), it provides shade (9%)

and clean air (9%). Respondents stated that because Richards Bay Minerals cuts trees and

pollutes the air, it is very important for them to protect nature to counter this impact.

Respondents reported the following ecosystem goods and services:

•fishing and harvesting of mussels (15%)

•wood for building houses and kraals (20%)

•grass for roofing and reeds for weaving (5%)

•trees for firewood (36%)

•food (vegetables and fruits) (13%)

•medicinal purposes and cleansing (26%)

•shade from trees (10%)

The environment supports livelihoods in Sokhulu with the environmental wage being valuable

to between 20% and 36% of households in different ways, which is significant.

Socio-economic aspects

In the baselines survey undertaken, 20 households were interviewed in May 2024 in the

following seven villages: eHlawini, eHlanzeni, kwaNtongonya, Ethukwini, eMalaleni,

kwaManzanyama and kwaHolinyoka.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Male and female headed households are reasonablyevenly balanced at 49% and 53%

respectively. This is somewhat higher than the national average for 2022 of 45,7% female

headed households in rural KZN. (StatsSA, 2022).

The average household size for the village is 7,8, compared to the national average of 3.4,

with households ranging from between3-25 individuals. The dependency ratio for these

households is extremely high.

In terms of age, the population in Sokhulu is skewed significantly towards the age

group of 0-18 years.

Age group in years

StasSA %

Sokhulu %

0 -18

28,8

45

19-34

35,1

30

35-59

27,1

20

>60

9

5

The large proportion of children under the age of 18 years in this area is likely a combination

of the community being well settled in the region (little in or out migration) as well as access

to services such as healthcare and schools (specifically high schools). This differs significantly

6

from the northern villages inside the IWP, where the proportion of children under 18 years is

much lower.

Incomes and livelihoods

Of the 140 households interviewed 138 households (95%) fall below the national

poverty line (R1558/month/capita income). This is because the households have on

average 7,8 members and are quite large. This number is skewed by a small percentage of

very large households as reported by respondents. If this is considered, then around 66% of

households fall below the poverty line. This is more reasonable when compared with other

data, showing quite a high degree comparatively, of formal employment in the regionas well

as small businesses and self-employment.

Income range in Rands

No

Percentage

Cumulative percentage

0-1000

3

2,2

2,2

1001-2000

29

21,0

23,2

2001-3000

29

21,0

44,2

3001-4000

23

16,7

60,9

4001-5000

4

2,9

63,8

5001-6000

9

6,5

70,3

6001-7000

7

5,1

75,4

7001-8000

1

0,7

76,1

8001-9000

4

2,9

79,0

9001-10000

6

4,3

83,3

>10 000

23

16,7

100,0

Total

138

98,6

100,0

The following income categories were mentioned by the participants – own business and small

businesses were considered different categories. Own business included farming, forestry

taxis, transport and similar businesses while small businesses were more along the lines of

spazas, resale of clothes and meat and similar activities. A proportion of the community makes

a reasonably substantial income from both farming and forestry (contracted to SAPPI).

Income categories

No of hh (n= 140)

No of individuals

% individuals

Formal employment

31

40

6%

Contract workers

56

56

9%

Own business

28

28

5%

Small business

30

32

5%

Social grants

132

313

94%

Unemployed

124

318

51%

The unemployment rate is very high in this area, indicating that around 88% of households

have unemployed adults living there and 51% of working age adults are unemployed.Levels

of unemployment are much higher than the national average of 32,9% (StatsSA, 2024).

Reliance on social grants (pensions and child grants) as an income source is very high, with

94% of households receiving grants. A number of households mentioned that they receive

remittances from family members who do not live in the area.

Food shortages are common, with 93% of households mentioning that they experience

a shortage of food. Shortages are experienced for some households during winter

(40%), summer (67%) and throughout the year for 9% of households.

Agriculture

Agriculture in the form of cropping and livestock husbandry is extensively practiced across

Sokhulu, albeit at different scales. Around 71% of households undertake cropping in gardens

(more intensive with some irrigation) and dryland fields which are largely in the flood plain.

Access to fields in the roughly 400haof cropping fields on the flood plain is open to all 7

7

villages, and access is generational, with a growing rental market as all land has been claimed

over the years, but not all families use their allocations on an ongoing basis.

The table below summarises the extent of agricultural activities in Sokhulu

Table 1: Extent of agricultural activities across Sokhulu, May2024 (n=140)

Activity

% of HH

Units

Comments

Gardens

68% (31% male,

37% female)

100m2-

1000m2

gardens are either quite small and at homestead level or

further away in wetland areas or the flood plain

Fields (flood

plain)

22% (9% male,

13% female)

1ha plots

Fields are in 1ha portions, where farmer mostly have

between 1 and 3 fields.

Fruit

production

19%

1-4 trees per

household

and ~20-100

at field level.

Trees include oranges, naartjies and bananas – grown at

scale in the flood plain and trees such as avocadoes,

mangoes and lemons planted more frequently at

household level.

Poultry

35%

Ave 14

chickens

Poultry consists of traditional chickens which roam freely

as well as small production units of broilers.Keeping of

layers is not common.

Goats

25%

Ave 12 goats

Goats roam freely, some homesteads have kraals but not

all

Livestock

25%

Ave 10 cattle

(2-50)

Cattle roam freely.Herders are employed. There is

conflict in the community from cattle invasion into fields

and gardens.

Crops commonly grown in the area are shown in the table below in decreasing percentages.

Interestingly participants who indicated ‘none’ as their crops, are those whose fields have been

inundated due to the back flooding from the closure of the mouth some eight years ago. This

gives an estimation of the lost fields as being around 23% of the total area. Sweet potatoes,

amadumbe and cabbages are the most common crops grown. In the dryland fields (on the

flood

plain) the most common crops grown are

sugar cane, sweet potatoes, amadumbe,

beans,

maize and bananas. It is clearform the

crop choices that farmers in the area

have adapted to cropping in these

wetland conditions with cyclical flooding

and water logging. Crops such as

amadumbe and bananas are planted in

the wetter areas of the fields and can

withstand high levels of water logging.

Irrigated crops consist of the vegetables

such as cabbages, spinach, onions,

lettuce, carrots, beetroot and tomatoes.

Below are a few indicative pictures of

farming in the floodplain

Figure 1: Above left: A typical dryland field in the flood plain planted to sugarcane and bordered with bananas and

Above right: Smaller fenced garden in the lower lying areas, close to sources of water producing crops such as

sweet potatoes, beans, cabbages and onions.

CROP

Percentage of respondents

Sseet potatoes

50

cabbage

43

amadumbe

39

spinach

30

onion

27

lettuce

22

None

23

potatoes

19

maize

18

green pepper

14

carrot

14

beetroot

14

tomatoes

12

oranges

10

naartjies

8

sugar cane

8

banana

6

8

Infrastructure

Uncontrolled development and haphazard management of small-scale gum plantations in the

area and these in addition to climate change impacts have led to a drastic decrease in in the

groundwater as well as wetland areas (around 36% reduction) in the last decade. These

issues combined with the

RBM mining and dunes, which

has changed the water flow

and management of the entire

area has had the outcome of

inundation of lower lying areas

leaving some homesteads

and fields under water, with a

drying out of the higher lying

areas with too little access to

water and drying out of

boreholes there.

Figure 2: A typical view of the poorer homesteads in the area. People have come into the area from as far as

Manguzi due to the work opportunities provided through the mines and the timber industry.

Figure 3: A view of a typical homestead in Sokhulu surrounded by a patchwork of gum plantations. In the foreground

a small swamp has formed close to the homestead, a trend that has increased in recent years, thought to be due

at least in part to the huge RBM duneschannelling water into this area both underground and as runoff from the

dunes. The ’hill’ in the background is a large, rehabilitated mining dune.

Given that the communities in Sokhulu have access to livelihoods options such as small scale

forestry, field cropping and livestock, which has provided for a reasonable and in some cases

substantial income for a proportion of the households and that thesecommunities have

ongoing development support (however badly managed) through RBM, the Umfolozi LM and

the Department of Agriculture, the overall situation in terms of livelihoods and poverty here

differs somewhat from villages inside the IMPA. Basic service provision through roads,

electricity and sanitation is more evident in the area.

9

The graph below summarises infrastructural considerations in Sokhulu.

As shown in the types of services graph below the following further differentiation in service

provision can be made:

•Although access to electricity it available to the whole of Sokhulu (97%), use is limited

to around 84% of the community. Use of firewood for both cooking and light is equally

common (88%) and community members also use gas (21%) and paraffin (7%) for

appliances such as fridges and stoves. Firewood is cut locally from the numerous

plantations surrounding the homesteads and natural bush and forests.

•Water access of 35% at household level relates to access to taps in household yards

(22%) and 10% of households having JoJo tanks for rainwater harvesting. The 63%

without access to water at household level are likely to have some access through

communal standpipes or having to rely on water provision through Municipal water

tankers. In community meetings held the issue of lack of access to water was raised

as an immediate and important concern. It appears that some small borehole

dependent water schemes reticulated to communal standpipes have run dry and that

provision of water by the municipality in these cases has been very intermittent.

•Toilet access of 97% relates pit latrines, either supplied through the municipality,

development projects or home built. Only 3% of households have access to

waterborne sewage – the assumption here is that these household have their own

septic tanks, as there is no sewage network or treatment in the region.

•With respect to housing, 29%of households have had support from government in the

form of RDP houses. This signifies a large state intervention in housing support for the

Sokhulu community as this percentage of support is considered substantial when

compared to other rural communities both in the region and in rural areas of KZN more

generally.

•There is no municipal solid water collection process in Sokhulu.

•Cell phone reception in the area is limited with only 34% of community members being

bale to access networks such as Vodacom and MTN.

•With respect to roads, 59% of respondents mentioned that accessisprovided by

gravel roads and the other 41% responded that there were no roads.Away from the

long stretch of unpaved road providing access into Sokhulu (which is not in a good

condition), the smaller tracks in and around villages have been made by locals for

access to surrounding bush and plantations as well as the floodplain. These tracks

haven’t been officially graded but are rough approximations of roads made through

use. Due to the sandynature of the region, these can quickly become impassable

when used by heavy vehicles such as tractors with trailers and also when wet.

Electricity

Water in

household

or yard

Toilets RDP HousesWaste

collection

Network

connection Roads

Available 97 35 97 29034 56

Not available363 367 98 66 41

0

20

40

60

80

100

Percentage

Access to services

10

The access to services is also reflected in the development needs and priorities mentioned by

respondents, as shown in the graph below.

Respondents focused on the need for reliable access to drinking water, job opportunities,

roads, education and opening of the river mouth. A thread passing through all these requests

is the need for equity in provision of services.

Social organisation

The proportion of respondents who belong tosocial groups/organisations is limited to 38%. Of

these the following groups are active in these villages:

33%

Burial societies

72%

Stokvels

21%

Church groups

5%

Women’s groups

Similar to other rural areas, the larger proportion of women belong to these groups and us

these social organisations to provide economic and social safety nets for themselves and their

families.

Both the Local Municipality and the Traditional Councils (TCs) are important in Sokhulu for

access to services and development and conduct meetings in the community which are

reportedly well attended. Development and farming committees are linked to the TCs. Despite

strong participation and reliance on these institutions only around 43-56% of respondents felt

that they could trust these institutions. A typical explanation from these community members

revolves around the need of the community to be involved in decision-making, equity across

Eskom tank Tap Pit

toilets

water

toilets

Govern

ment

self

built All Vodaco

mMtn gravel

Electricity Water Toilets House Network Roads

Series1 9710 22 94329 49 17 11 59

0

20

40

60

80

100

Percentage

Typesofservices

7

60

43

12 715 22

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

livestock ruin farms

BadRoads

Water accessbility

Empty promises/unfair treatment

Lack of businesses

Closure of the estuary

Employment

Remote location

Percentage

Main development challenges

11

villages and community members in terms of benefit from services and projects and the need

for these leaders to provide feedback and information to community members.

Natural resource management

Human intervention has substantially impacted on the ecosystems of this flood plain, primarily

through vast expanses of gum plantations (commercial forestry commenced here around

1933), sugar cane (started around 1959) and dune mining (RBM started these operations in

2004), the longer-term impacts of which are now becoming evident through both a substantial

reduction in the groundwater and water quality issues in the area and the consequences of

channelisation of the local rivers – the latter which has also impacted heavily on coastal and

mangrove ecosystems and the loss of wetlands.

The Sokhulu traditional council area is based at the southern tip of the Isimangaliso Wetland

Park, with only the previous eMapelani Reserve area incorporated into the reserve itself, a

point that is seemingly not well understood by either the TC or the community members. This

area is further north towards the coast with the confluence of the St Lucia estuary and the

Umfolozi and Umsunduze rivers and is not populated, as people were removed from there

when the Wetland Park was formed in the late 90s’. The Sokhulu villages/isigodi that abut on

this area are Ehlanzeni and Ehluwini, where the Sokhulu Traditional Council office is housed.

In the past, prior to the establishment of the IWPA, tourism activities created some income for

the broader community. The eMapelani Reserve area is one of the 14 odd land claims that

have been lodged against the park. At the same time, the Sokhulu community trust is

benefiting from an annual payment from the reserve. Funds from this payment is meant to

support the fenced communal crop lands (roughly ~200ha) on the floodplain, supporting with

tractors for ploughing, input subsidies and transport of produce from the plain to collection

points in the villages higher up.Presently this committee is under review for misuse of these

funds.

Community members understandtheir impact on the environment, with close to 90% of

respondents feeling that it is important to protect the environment. All community members

use local resources for grazing oflivestock, harvesting reeds and medicinal plants,harvesting

wood (buildingand firewood) as wellas marine resources (fishing and coastal harvesting),

mainly for food. As mentioned,agricultural production is common in the area.

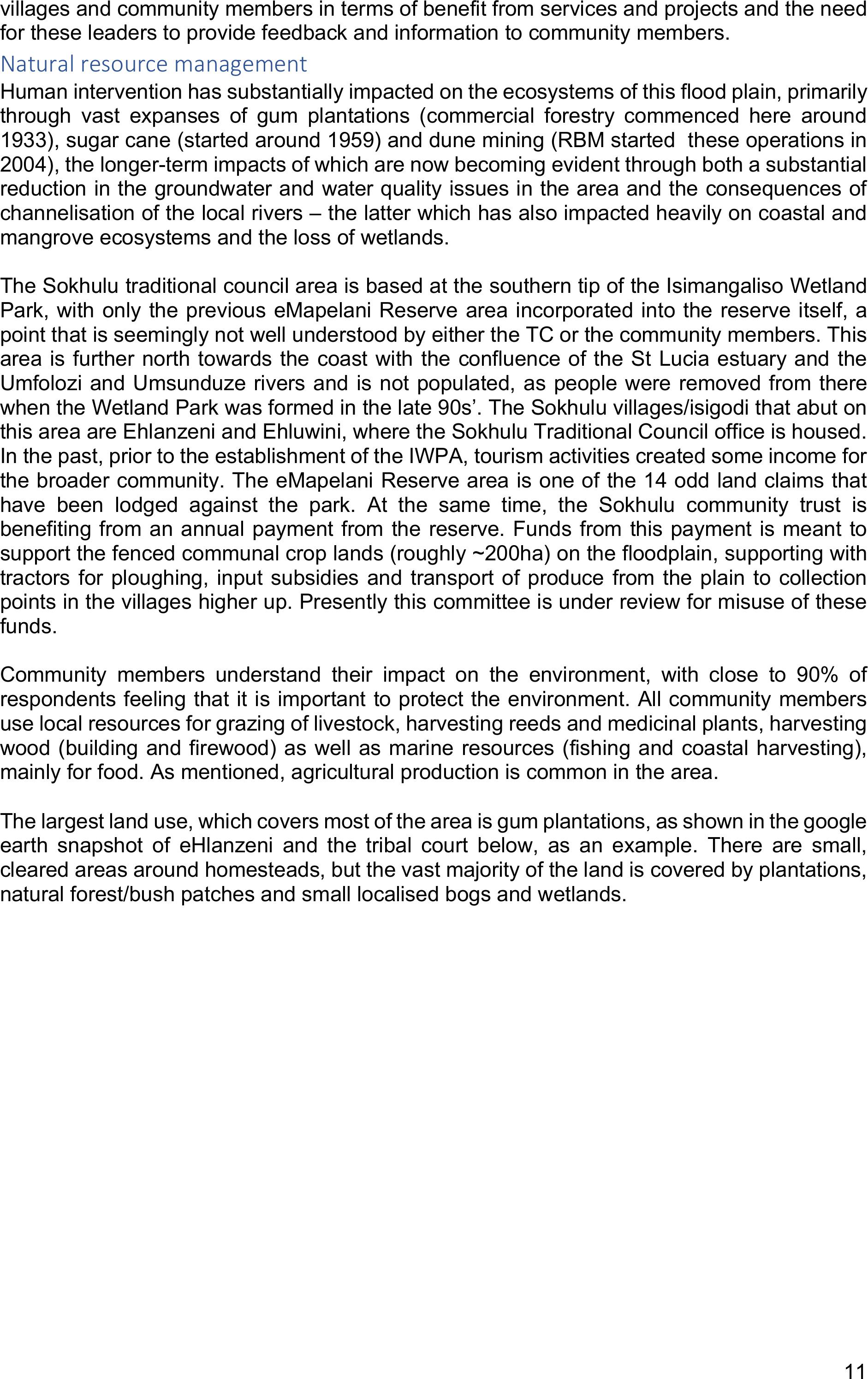

The largest land use, which covers most ofthe area is gum plantations, as shown in the google

earth snapshot of eHlanzeni and the tribal courtbelow, as an example. There are small,

clearedareas around homesteads, but the vast majority of the land is covered by plantations,

natural forest/bush patches and small localised bogs and wetlands.

12

Figure 4: Spread of plantations in the Sokhulu area

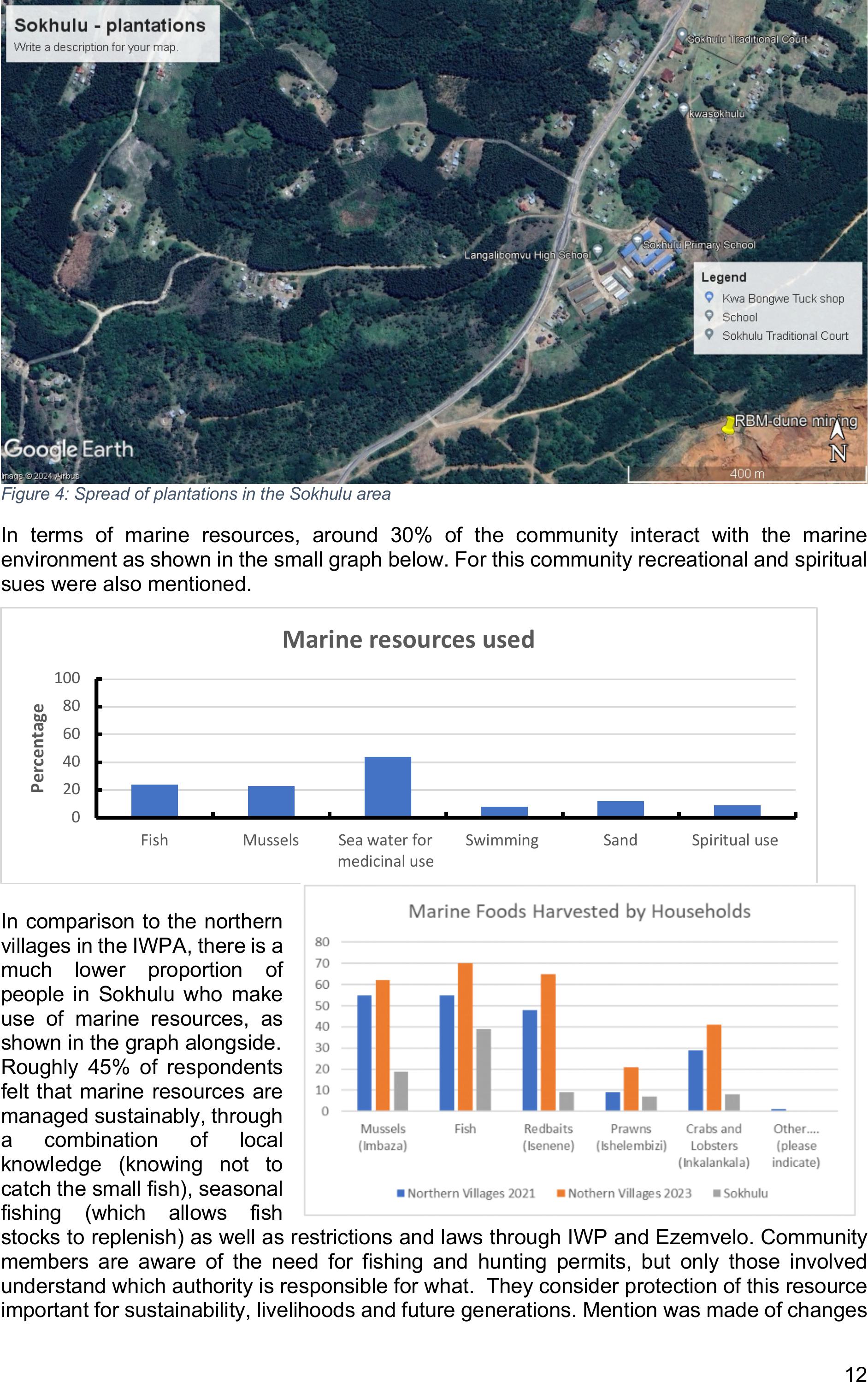

In terms of marine resources, around 30% of the community interact with the marine

environment as shown in the small graph below. For this community recreational and spiritual

sues were also mentioned.

In comparison to the northern

villages in the IWPA, there is a

much lower proportion of

people in Sokhulu who make

use of marine resources, as

shown in the graph alongside.

Roughly 45% of respondents

felt that marine resources are

managed sustainably, through

a combination of local

knowledge (knowing not to

catch the small fish), seasonal

fishing (which allows fish

stocks to replenish) as well as restrictions and laws through IWP and Ezemvelo. Community

members are aware of the need for fishing and hunting permits, but only those involved

understand which authority is responsible for what. They consider protection of this resource

important for sustainability, livelihoods andfuture generations. Mention was made of changes

0

20

40

60

80

100

Fish Mussels Sea water for

medicinal use

SwimmingSandSpiritual use

Percentage

Marine resources used

13

in the marine environment which included depletion of fish stock due to changes in climate

and also due to there being too many fishers. They also mentioned that the mangroves have

reduced a lot and what was left has died back in the last eight years due to the closure of the

rive mouth. This has reduced their function of managing water levels in the lower lying areas

as well as reducing the marine resources such as crabs and certain fish.

In Sokhulu, the villages engage less with IWPA, with only 8% of households obtaining contract

work through IWP management activities, 3% obtaining access to bursaries, 4% stating that

they get support for their gardens, and 70% stating there are no benefits. The table below

outlines what community members know about the IWPA.

There is a reasonably large number of community members who believe the IWPA closed the

river mouth (35%). Others believe it was done by Richards Bay Minerals (RBM). In general,

there is an inherent understanding of the cyclical nature of the wetland system and the impact

of channelisation on the system. For most community members, but specifically the farmer on

the floodplain this is understood as a positive intervention.

2.1.3 Recommendations for intervention from baselines

Recommendations

ØWorking with village-based groupsof farmers to explore adaptive measures and

climate resilient agriculture practices and to set up a process of experimentation with

different options and ideas to improve the management of water and soil on the

floodplain as well as at the homesteadsor the smaller communal gardens.

ØTaking some soil and water samples across the flood plain to ascertain the fertility and

quality of the water (there is suspicion among community members ofpoisoning of the

water through the RBM mining operations).

ØComparison ofconditions on the floodplain in winter and summer, as well as further

discussions with key informants about channels, patches of natural vegetation, flood

control and scenarios for management. This will need input from agricultural engineers

and hydrologists, as well as some form of mapping.

ØEngagement with the community for awareness raising and information provision

around the functioning of the system, the impacts of closure and opening/dredging of

the river mouth and the impact of different land use practices, to better inform more

sustainable landuse practices.

ØContinuation of liaison between MDF and the Wildtrust restoration team to allow for

village-based clearing of unwanted gum plantations and recovering these areas as

productive land, through agroforestry systems.

ØFarmers have asked for irrigation options, fencing and dredging of the Msunduzi

mouth. They are open to trying out new ideas and crops,such as mulching,

conservation agriculture, fodder crops and possibly rice, but warned that people on

Protect our

coast

Protect our

nature Don’t know

It closed

the river

mouth

Same as

Wildlife Hire peopleNo fishingEmpty

promises

Series1 813 21 35610 5 5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Percentage

What do you know about IWP

14

these plains have been doing the same thing for a long time and would be reluctant to

change.

ØIWPA to engage more constructively with the community in terms of information

provision, outlining rules and regulations and appreciation for the livelihoods

constraints of the community members.

2.1.4 Climate change adaptation (CCA)workshops

Mabibi Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) workshop

Following the finalization of CCA workshops with the community, attention shifted to the YES

interns where it was their turn to put the climate change topic into a bit more perspective.

These workshops are2 to 2,5 days and includes an assessment of climate change impacts,

Seasonality diagrams (temperature and rainfall) to visualize changes, discussion ofscientific

and community understanding of changes that are occurring, practices and activities in the

villages in the past, present and future. Suggestions for adaptive strategies form the group are

discussedand these are in relation to water, soil crops, livestock and natural resources.

In Mabibi the 2-day process included preparing trenches and organic matter that goes into the

trenches with the second day taking the whole group through the idea on deep trenches,

organic matter and shade tunnels, mulching as one strategy to climate change adaptation

practice.

Mabibi is a small community in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, also known as Zululand, situated in

a wetland and a proclaimed national park under the management of iSimangaliso and

Ezemvelo. The community consists of smallholder farmers with livestock such as cattle, goats,

and traditional chickens. They also have household gardens where they grow vegetables and

field crops like maize, sweet potatoes, cassava, and nuts. However, production has declined

due to intense heat and reduced rainfall. Some farmers have stopped tending to their gardens

because crops are either not growing or are spoiled by too much rain. Others face pest issues

in their gardens.

The purpose of this workshop is to train the YES youth group and Hub staff on innovative

ways to assist the community in adapting to climate change. First, they must understand the

concept of climate change, how it occurs, and how to mitigate its effects.

Past, Present, and Future

Past

•About 90% of households used to grow watermelons, but now it's difficult.

•Imbuya (indigenous spinach) and iskilwane (wild tomatoes) used to grow in grazing

lands.

•Indigenous fruits like Bonsi, Amathundulula, Amavilo, Inonsane, Amatemela, and

Amadongwa thrived in the park.

•Sugarcane was also widely grown.

Present

•Temperatures in the community are rising.

•Isibhayi Dam is decreasing in volume, making it harder to catch fish.

•Springs within the park are drying out.

15

•Rainfall is inconsistent, and pumpkins are rotting before maturity due to extreme

weather fluctuations.

•Tornadoes have been reported along the coast.

•Alien invasive species are spreading in the park.

•Wildlife in Mabibi is relocating as their food sources are disappearing.

Future

•Droughts will become more severe.

•Lake Sibaya may dry up completely.

•Both commercial and subsistence farming may cease.

•Livestock production will decline due to drought and poor grazing.

•National economic collapse and widespread famine could occur.

•Unemployment, poverty, and crime will increase.

•Tourism in the area will decline.

•Indigenous plants and herbs will go extinct in the wetland, and invasive species will

take over the park.

Scientific Presentation on Climate Change

SAEON presented research on climate change impacts in South Africa, focusing on recent

events like tornadoes, hurricanes, and floods. The youth group connected the presentation to

their own observations, including a recent tornado along the coast that damaged households in

Enkovukeni. The presentation also highlighted the declining water levels in lake Sibaya,

exacerbated by gum plantations.

Seasonality Diagrams

Two groups were tasked with creating charts to depict current rainfall and temperature levels.

The first group found that temperatures have been steadily rising, shortening winters and

disrupting seasonal patterns. The second group noted that while rainfall seems to follow

traditional seasonal patterns, it is less effective, with shorter, less beneficial showers.

Possible Solutions by the YES Youth

Figure 5: Groups presenting their seasonality diagrams

16

•Reduce the number of plantations (such as Gumtrees) in the area

•Promote the clearing of alien invasive species

•Establish firebreaks and encourage fire monitoring

•Replant indigenous trees and plants that have disappeared

•Reduce livestock density to prevent overgrazing and erosion

•Stop the burning of veld (grassland) in the community

Climate-Resilient Agricultural Practices

Following the workshop, the focus shifted to agricultural practices aimed at combating climate

change. Many community members have stopped growing crops due to high temperatures,

droughts, and pest problems. Those still trying face additional challenges, including lack of

water. Practices such as deep trenches, micro-tunnels, and tower gardens are being introduced

to help mitigate these issues.

The YES youth and Hub staff will monitor the implementation of these practices, adjusting

based on the needs of each field. For example, a farmer with a steep field might implement

contour farming, while those facing water scarcity may benefit from micro-tunnels or trench

beds.

Demonstration Day

On 18 September 2024, a demonstration took place at the household of Hlengiwe Makhanya,

who met the criteria for showcasing climate-resilient farming methods. The YES youth

observed the construction of micro-tunnels, which began with digging deep trenches for

planting beds. Layers of green and dry matter, along with cattle manure and soil, were used to

create fertile planting beds. After constructing the tunnel, seedlings of diverse crops—such as

beetroot, kale, spinach, and herbs—were planted to promote biodiversity, which helps control

pests. Mulching was applied to regulate soil temperature and moisture and to improve soil

fertility.

Figure 6: YESteam preparing trenches at Hlengiwe Makhanya’s

17

Three tunnels have been installed in this village, benefiting Nomahlathi Thwala, Sibongile

Ntuli, and Hlengiwe Mkhanya, all of whom meet the criteria as heads of their households.

Materials had to be sourced from outside the households. The heads requested manure from

neighbors with livestock, and the field team and YES helped load and transport it. The same

was done for organic matter, with a large pile from grass cutting and maintenance at the hub,

which was transported in two truckloads to the sites and used to fill the trenches.

Nomahlathi is an elderly woman living with her grandchildren, with grants being the

household's main source of income. When the field team arrived, she was emotional, pointing

to her children's graves in the yard. Her eldest son passed away while halfway through building

her house. The tunnel will allow her to grow fresh vegetables year-round, complementing her

field crops like peanuts and maize.

Figure 8: Nomahlathi Thwala delighted at her tunnel where she will be growing vegetables

Figure 7: YES team putting up its first ever tunnel

18

Hlengiwe Mkhanya, another household head, is part of the "missing middle" and supplements

child support grants by making mats. She has tried farming for household consumption, but

livestock have posed challenges. The introduction of a shade tunnel will improve her farming

efforts by keeping livestock out and enabling year-round cultivation. Of the three households,

Sibongile’s soil was the poorest—extremely sandy with little organic matter. Her trenches were

filled with the most organic material and manure.

The Ntuli family relies heavily on their garden, which has dark, fertile soil due to silt and

organic matter buildup. It was the only garden where we found earthworms. Located at the

lowest point of the property, the garden

retains moisture, and Sibongile has

dug two pits to collect water for

irrigation. When we arrived, she was

growing a variety of crops, including

spinach, onions, peppers, cabbage, and

peanuts. Sibongile also collects

incema, a type of grass, to make and

sell mats to supplement her income

from child support grants and her

pension.

Figure 9: Tunnel mulched with leaves at Hlengiwe Makhanya's

Figure 9: Dark soils with organic matter and earthworms at the Ntuli household with team digging trenches

19

In the absence of field staff, the Mabibi YES team along with extension officers based at the

hub visited Nonkululeko Makhanya and Sibongile Mbonambi; selected participants who fit the

criteria; and dug trenches. Upon the field team return to Mabibi on the 14th of October 2024, a

trench was put up at Sibongile Mbonambi where kraal manure was collected from a nearby

household. Poles were bent and left at Nonkululeko Makhanya’s and the field team managed

to successfully put up her tunnel.

Figure10:: Sibongile Ntuli's tunnel done and planted with seedlings

Figure 11: Mabibi YES team's first independently put up tunnel at Nonkululeko Makhanya's

20

2.1.5Two daytraining on gardening; establishing a garden, soil and water

This process consistedof a group theory session, where we looked at siting a garden, looking

at points to consider when placing a garden as well as living soil. This was followed by another

dayof working together on building a shade tunnel garden for1 of the 5 participants who were

identifiedby field staff along with hub staff since the communitynever pitched for meetings.

Figure 12: Nqobile delivering gardening presentation to the YES interns

Agriculture is one of the main livelihoods which the community of KwaDapha cherish and make

a living from and is mainly subsistence. The community members have livestock such as goats

and some have cattle. Majority of the community have gardens in their homesteads where

they plant vegetables, some of the fields crops such as beans and nuts, and they have fruit

trees within their households. The aim of this workshop was to provide a garden training to

the YES intern youth group who are stationed at KwaDapha Hub, this training will equip the

Interns with the necessary set ofskills, knowledge and bitof technical know-how to help

smallholder farmers within the community toimprove their agricultural standing through new

agricultural practices seeking to increaseresilienceto climate change and are environmental

sensitive.

The workshop wasdivided into four sessions, the first sessionwas an activity for theYES

intern. They were requested to come up with the garden layout they know in their communities,

draw them on the flip charts provided and present them afterward. The second sessionwas a

discussion on garden layout focusing on aspect, slope, wind as well as waterand soil

management. The third sessionfocused on living soils, which focused on soil structure, soil

fertility andpractical practices seeking to increase fertility in the soil for better crop

performance.

21

Current garden drawing presentations

The YES interns weredivided into three groups where they were requested to come up with

a garden layoutthey knew of. In this exercise the groups were asked to draw a garden they

allnew or from one of their homes and were grouped into their communities they come from,

these drawings were to include types of crops planted in the garden, where they get water for

irrigation, types of practices involved in the garden. Then were also asked to give detailson

their layout on garden slope, aspect, water pathways after heavy rains and wind direction.

Oneindividual; Mqondisi; was asked to dohis layoutalone and the reason behind that was

the fact the has his own garden on abit of alarger scalewhere he grows for both eating and

selling. Afterwardsthat they were asked to appoint one member to present their layout on

behalf of the entire group. The main purpose of this exercise was to get to know some of the

activities practised in this areain details, but most importantly to pick up whatthe YES intern

understands about gardening in general.

Presentations done were

from the KwaDapha,

Nkathweni, Emasakeni

and Mvutshana

communities. According

to the presentation and

the drawings in their

chat, most crops planted

were carrots, spinach

and cassava and they

were all mono crops. The

farmers are struggling in

water access however

they managed to get

water irrigation from

water stored in JOJO

tanks (rainwater) and

some have boreholes in

their households. One common technique or practice in obtaining water is, farmers would dig

a few metres down at any spot at the garden or cropping field and water would come out from

the shallow water tables and this is a practice in all communities. Another advantage is the

fact that the gardens are surrounded by trees meaning they are hidden from strong winds.

And most areas are not steep, hence the municipality’s name “Umhlabuyalingana” meaning

flatlands, so surface run-off is hardly an issue in this area. Wild animals like monkeys and

hippos are a huge challenge for the farmers.

Figure 13: KwaDapha group presentation of current farming practices

22

Figure14:: Emasakeni village garden presentation

From the presentations, farmers generally buy seeds and do their own seedlings which they

transplant in the bigger plots fences with branches, nets and iron sheets. These seedlings are

produced closer to tall trees under shade and watered. Birds are a hugeproblem as gardens

are done in between naturalvegetation and tress, scarecrwos are a practice in Nkathweni and

they seem to be deterring some birds, however, there has been an increase in birds camping

in garden and fields where participants in other villages stay out in the day chasing them away.

Kraal manure from cattle and gats are common fertility amendment used when growing food

where it is mixed with the soil before planting. Compost pits are also common, where organic

matter is plied in a pit and used at the base of the basins when seedlings are transplanted.

Some villages are exposed to pesticides and use pyrethroid based products to treat aphids

on cabbages and other leafy crops. Mqondisi in Mvutshana has access to and uses synthetic

fertilizers for his cash crops such as chillies and leafy greens. Interns did bring across that

crop selection also was influenced by water available in the wetlands area where they normally

do their gardens. Crops such as cabbages, amadumbe, banana and carrots are planted in

moist areas where these crops can flourish more as to opposedto maize for example which

doesn’t like too much water.

Mqondisi has been experimenting with summer cover crops in sunnhemp that he is growing

to replenish his soils with organic matter and nutrients. He saves seed from his sunnhemp to

plant the following season and rotates his sunnhemp with chillies and vegetables. His plots

never run dry as he has borehole water that he pumps to a tank and irrigates using sprinklers

when it gets too hot.

Garden layout and design

This section was a discussion which wasfacilitated by Nqobile Mbokaziwhere he started by

the garden layout which the YES interns were not aware of. Here he was putting emphasis

that gardens are not just made anywhere but careful consideration of aspect, north and south

facing slopes,must be looked at. Aspect has animpact on the performance of crops as the

north facing slops is known to be the warmest, this

23

Figure15:: Nqobile talking to aspect, wind, sun and slope to the group

is because when the sun rise in the morning, this aspect is the first to receive the sunlight,

and during the afternoon when the sunlight is intense it is also the first to receive shade. While

the South Facing slope is the opposite of the North facing slope. So,it is preferable to establish

your garden in the North facing slope.Wind is another important factor as it has the potential

to dry out soils. So, the garden must be protected from heavy destructive winds that will

damage crops. If not protected by buildings, gardens need a buffer in trees and shrubs that

will reduce the impact ofthe wind before getting to the garden. Yes, plants do need air, but

winds can eat away crops slowly like sandpaper if exposed.

The second factor which the farmer should also be mindful of is water management, there are

two events which can take place as far as water is concerned, the first one being too much

water in the yard of the farmer. This means if the farmer has a sloped area which encourages

surface run-off on the area,it is significant to know the collection points ofthe water during

rainfall and its direction. There are practices which can help the farmer to manage the situation

of toomuchwater in the yard, such as cut-off ditches and diversionfurrows. Farmers cannot

have gardens where water collects and sists nor do they want it at the driest part of the area.

So somewhere in the middle where run off can be either be slowed down or stopped thus

encouraging more infiltration and access to crops thereafter. Cut off drain and diversion

ditches arephysical alterations of the landscape and management tools farmers can

implement to control the water and channel it somewhere useful. The steepness of the slops

has great influence ofthe speed of water and its soil eroding capacity and this is crucial for

the sustainability of farming.

Living soils

This section was a discussion about soilmanagement facilitated by Mazwi Dlamini. A question

posed by the facilitator: Why do we use fertilizers to the soil? Most of the YES youth answered

by saying “We use fertilizers as means of trying to produce food” and some answered by

saying “To enrich the soil because of the situation were plants just dies”. Mazwi responded by

saying that fertilizers area temporary fix and not a permanent solution to the poor soil fertility

problem. Fertilizers are ratherlikepills which are like vitamins that offers a temporal solution

for specific deficiencies but does not solve the problem in the soil. Soil ailments are a result of

24

“mining” practices where farmers farm without replenishing nutrients back and they eventually

run low and run out. Much like unhealthy eating habits in human, coupled with excessive

drinking and lack of exercise, the body with not cope with threats thus making the person

prone to falling sick. Sound practices such as minimal disturbance, permanent soils cover for

organic matter and rotations keep the soil healthy thus crops perform well. Then he continues

by sharing the concept of the living soils, the soilis has life, it needs different kinds of nutrients

to stay alive, it needs water to survive and it also needs oxygen, nitrogen for healthy leaves

and stems, phosphorus for strong health roots and potassium for lowering and bearing fruit,

this lead to the NPK discussion that farmers buy in fertilizers. It is a farmer’s responsibility to

take care of the soil by making sure that all its needs are met so that the soil will take care of

the farmer, healthy soils can be identified through good organic matter and presenceof living

organisms in itsuch as earthworms. Healthy soil has good structure and are able to hold water

thus reduce run off.

Figure16:: Discussion on living soils by Mazwi Dlamini

There are three major nutrient which are observed when looking at the soil fertility, they are

Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium (NPK). This does not mean that they soil onlyneeds

these three nutrients, there are other nutrients needed by the soil which are significant as well,

however these three nutrients just have more seen results which are easily detected. For

Example, Nitrogen is seen on the leaves oftheplants, if the plant has insufficient nitrogen

leaves turn yellow or brown. Phosphorus providesthe plant with good root system and strong

stem and when the plant lacks phosphorus the leaves turn fiery red at the edge of the leaves.

Potassium helps the tree to produce and bear fruit and flowers.

There are organic ways to supplement these major nutrients in the soil without the use of

synthesised chemicals or nutrients. Cattle manure, Chicken manure, rabbit manure, planting

of legumes and cover crops can supplement Nitrogen in the soil. Bones, bone meal, comfrey,

chicken manure and wood ash can supplement Phosphorus and Potassium. A question from

the YES group: “If pig manure also recommended”. Mazwi: “ideally pigs do have a lot of

nutrients in their by product or manure, but the issue is pig usually have a lot of diseases

detected from them which end up being easily transferred to humans as well, so there are lot

of complicated procedures which are to be followed when dealing with pigs in general”

25

Acidity

Soil can also be found to be acidic which also one of the factors which cause the soil to be

unproductive. The PH of the soil should be always neutral which is represented by 7 in the PH

scale. PH of 6.5 or 7.5 is also preferable not less, and not more. Acidity is usually caused by

excessive application of fertilizers and can be neutralised by liming.Soils can be healthy and

acidic, thus making nutrients in the soil unavailable to crops leading to stunted growth.

Conclusion

A lot of information was shared in one dayand the day was quite long, the YES hada lot to

digest and reflect on. The training went well, the Interns participatedand 30 manuals were

distributed to the groupfor them to revisit these discussions, thesemanuals are also now their

“bible” as far as intensive homestead production is concerned and will provide them with

guides in assisting the greater community.

Day 2: Practical demonstration of practices

This was a demonstration day demonstrating where the group was goingto put into practice

what was discussed the previous day. The day would be a collection ofpractices for improved

gardening where water, soil, diversification, greywater and intensified production would be

exemplified. A construction of a micro tunnel, with trenches filled with organic matter and drip

irrigation along witha tower gardenmaking use ofa small space to grow food enough for a

household while using grey water to somewhatrelieve demand for water to irrigate crops were

to workwith and shown in detail to the group for them to be able to help implement thesein

the community.All preparations of the demonstration were done prior to this day, where most

of the required materials such as manure, and dry matter were collected and keptat the

demonstration site.

Most ofthe YES interns seemed to have forgotten the CRA practices discussion and some

information on the micro-tunnel and tower garden. A summary and a reminder of the CRA

practices specifically the micro tunnel and a Tower Garden was shared withthe youth group.

The first demonstration was the micro-tunnel where we started by measuring the site where a

tunnel was appointed, the measurement being 6m X 4m which are the measurement of the

tunnel. The second step was digging up the deep trenches with the measurement of 1metre

width 5 metres length and 1 metre depth, the YES group were given an opportunity to measure

and dig all three trenches under supervision of MDF stuff members.

26

Figure 17:The how and why of trench beds

Trench bedswere filled upby adding dry matter and manure creating layers on the trenches

from bottom until just above ground level. The first layer of the trenches is supposed to have

tins and bone, adding calcium and zinc in the soil, however these materials were not found

during this demonstrationand thus bonemeal was spread. Next was demonstrating the

bending of the steel-poles using ajigand joining the two-bent polesthrough a coupling

creating one ark shaped pole which makes the shape of a tunnel,then the youth were given

an opportunity to bed the rest of the poles and joined them using joints. The back of the tunnel

and the front of the shade tunnel structure were sown in using the poles and the netwith field

staff demonstrating this and handing over to the group to try out.

Figure18:: Demonstration and bending of pipes by the group ahead of tunnel construction

27

After the back and the front of the tunnel were created and all the poles were joint, the following

step was to install the poles to the ground. A huge disadvantage in this demonstration site is

the fact that the soil or the ground is very sandy with looseparticles making it difficult for the

poles to stand strong in the ground. Having this knowledge before time was a real game

changer to this situation as we have planned for it. The plan was to make concrete and hold

it using 5Litre bottles then make a 14cm deep hole at the centre of the bottle which is a perfect

size of the steel-pole, the idea wasto use this concrete as an anchor of the steel-poles giving

the tunnel strength to stand still underground.

After the poles have been grounded strong tothe ground, the lastpiece of the net wentover

the poles and sewed to the pole starting from the top of the pole to the bottom covering and

completing the tunnel. Upon finishing the tunnela sense of pride filled the atmosphere as the

YES youth were soexcited and proud of their efforts. Afterthe tunnel was completed, 120

seedlings were planted on the trench beds (kale, mustard, spinach, chinese cabbage, brinjal,

thyme, coriander, parsley, chillies and onions).Particular attention was given to how the

seedlings were combined where we looked at leafy crops, bulbing crops as well as herbs. It

important to have a diversity of crops in your beds where onions, chillies, parsley, thyme and

coriander can protect greensliked by pests. The diversity in the garden makes it difficult for

pests to “target” spinach, cabbages and other vegetables. The different crops also use

different nutrients and have different water requirements thus reducing competition. Farmers

also have a variety of crops to choose from thus increasing intake of various nutrient with

herbs such as parsley aiding in blood pressure reduction while thyme help fight off bacterial

and fungal infections. Lastly, drip irrigation system; prepared by the YES groupwerealso

demonstrated and installed in the tunnel.

Tower garden

During the climate change workshop, a tower garden was demonstrated on one of the

homesteads in the community. The Yes Youth was presentduring the demonstration, this time

the tower garden was to be installed at the community hub it was a chancefor the YES youth

to show how much they remembered. They started by mixing cattle manure with the soil

because they had already sewed the net together. They then used a five-litre bottle cutting its

top and bottom leaving the body of the bottle throughout.

The hollow bottle was used to make the stone column in the centre of this garden held by the

soil-manure and wood ash mix.This process was repeated until the garden stood talland was

plantedin the body and at the top. However, they had forgotten the guideline for using grey

water in the tower which is like the drip irrigation system as well. They were then reminded

that grey water is not used right after being used, but it must first be kept in a drum with wood

ashadded to flush out the soap and chemical and neutralise before it can be provided to

crops. Importantly, crops do need fresh clean water once a week to wash themselves of the

greywater.

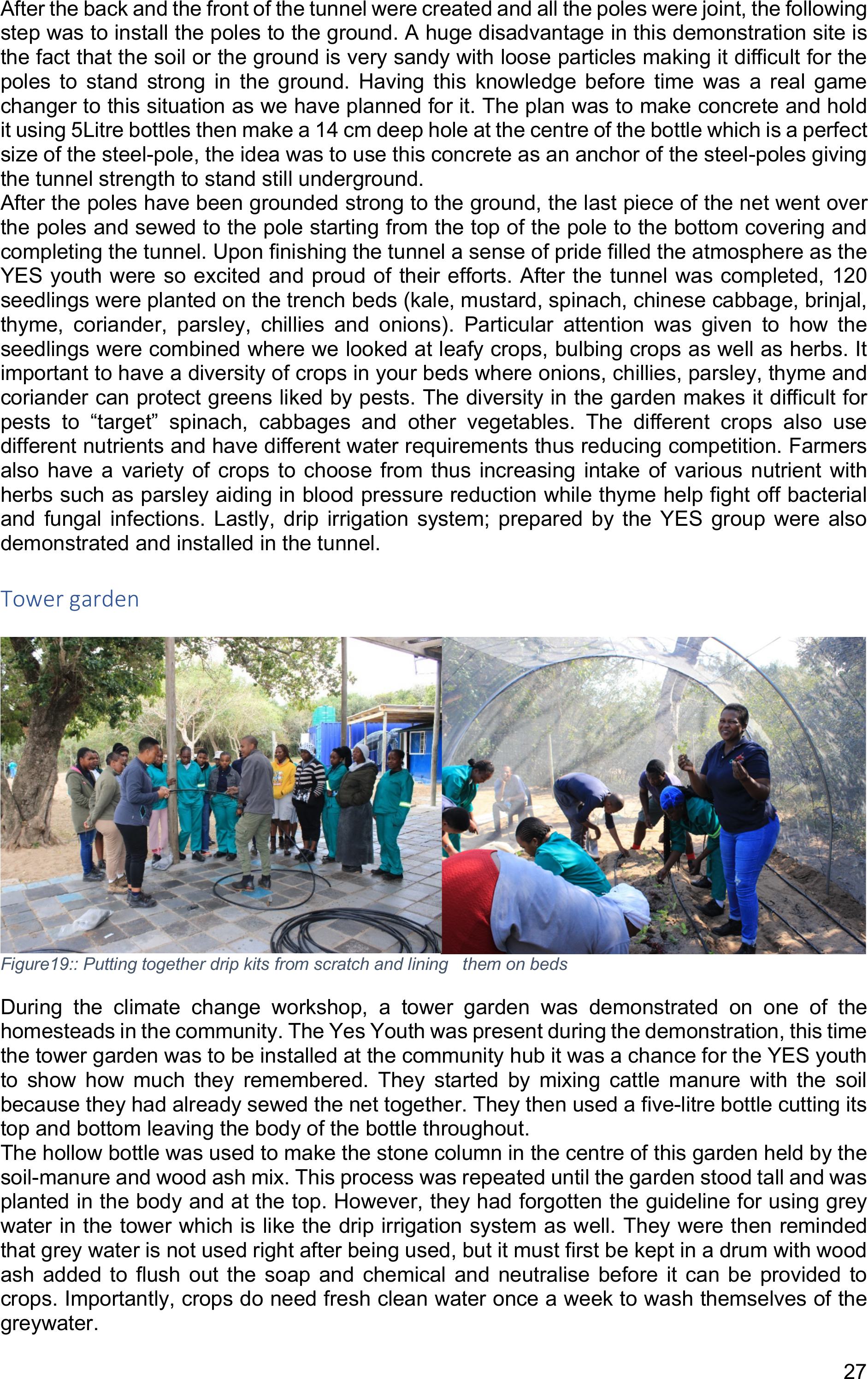

Figure19:: Putting together drip kits from scratch and lining them on beds

28

Figure20: Planting the tower garden

29

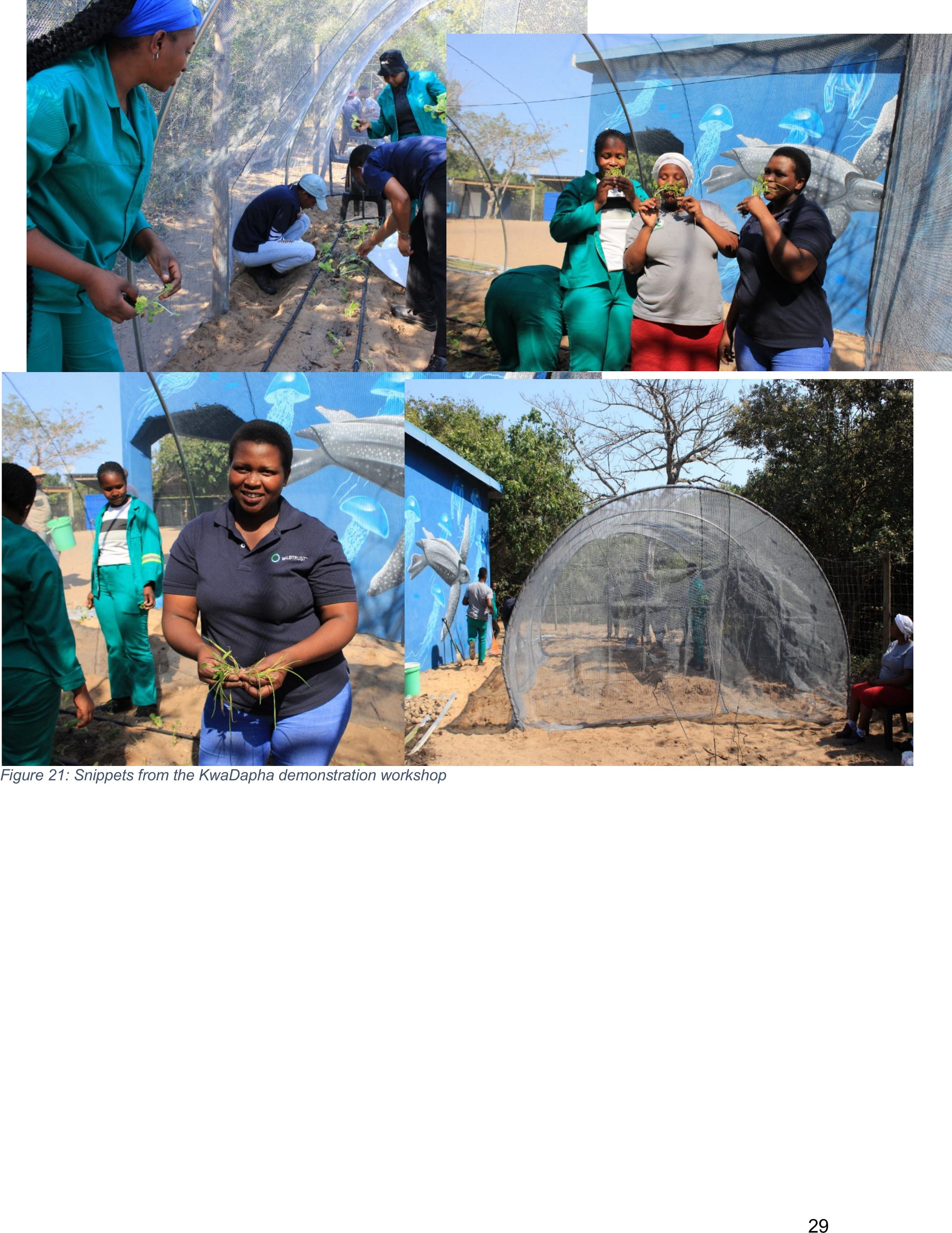

Figure 21: Snippets from the KwaDapha demonstrationworkshop

30

Figure 22: Tunnel construction at Bhekiwe Ngubane

Enkovukeni is one of the communities along the coastline feeling and witnessing the impact

ofclimate change. Because of this reality, most of the homesteads in the community have quit

farming in the field and in the gardens which greatly increased the issue of hunger and

malnutrition in the community. Therecent storm in the areathat occurred in the winter season

destroyed people’shomesand whatever crops left and villagers are still putting their lives back

together months after.

As means of trying to assist the community, climate changeadaptation workshops were done

with boththe communityand YES group. This was important so they have a better

understanding of climate change from both a global and local scale andto look closely at their

current situationin relation to climate for better planning, implementation and reflection

throughtrying new farming practices. The idea is to encourage as many farmers as possible

to implement Climate Resilient Agricultural (CRA)practices in their households, with the

assistance of the YES interns stationed at Enkovukeni hub for better outcome from their

farming activities. For the YES interns to be capable of assistingvillagers, must undergo

trainingsessions, looking at climate change, its impacts and possible solutionsthey employ

in assisting farmers.

The second step which we are currently at is to equip theYES youth with Garden training,

which will suit the implementation of the CRA practices. This training was set to take place at

Enkovukeni from 27thof August to the 29thof August, starting with the theoretical site of it and

ending with a demonstration of one of the CRA practices. Because of the weather threatening

rain, it was decided that we start with the demonstration, which was installing a micro tunnel,

as we can have a theoretical part of the training under a shelter of Enkovukeni hub.

This demonstration tookplace at one of the households which was chosen as one of the

beneficiaries most vulnerable in the community. Bekiwe Ngubaneis a household head and

one of the most vulnerable households head living with her unemployed daughter and

grandchild. She is one of the people who were severely impacted by the tornado which

31

destroyed her home and gardento theextent that they had to construct temporary shelter of

iron sheeting as their house was destroyed.

Demonstration (Micro-tunnel)

The 27thof August was a preparation day, where deep trenches were dug, material such as

cattle manure and dry matter were arranged, and concreate stands were made. On the

demonstration Day, a brief recap on the climate change workshop and the CRA practices was

discussed as a reminder to the YES intern as most of them had forgotten. The first step was

filling in the trench bed to make a seed bed. In a total of three deep trench beds, each bed

had a width of one meter, five meters in length and one meter deep. The first layer of the

trench had to have tins and bones, unfortunately the hub staffcould not obtain these materials

within the community, as a result we fist layer started with moredry matter, which were fallen

leaves from the trees, and some were leaves from dead trees. Because we did not have tins

and bones, we applied more dry matter and manure in the trencheslined with bonemeal, the

first layer being dry matter and the second layer being cattle manure, the cyclecontinues until

the trenches are full andbeds are made.

Figure 23: Filling up trenches and making beds

The second step was bending the steel poles to make that ark shape using a geek which is a

tool used to bend steel poles. This activity was demonstrated onto them, and they were given

an opportunity to bed the rest of the poles. The third step was to join the poles using a steel

joint creating that perfect ark shape giving a picture on the framework ofthe tunnel.The fourth

step was creating the back of the tunnel and the front of the tunnel with an entry point. It was

demonstrated on making the back of and the front of the tunnel, the important key is making

sure that the poles are 4 meters wide and sewing the net to the poles, making sure that the

net is tight on the poles and not sagging. With supervision, YES youth were able to make the

back of the net and the front.

32

Figure 24: Joining poles and sewing on of nets

The Fifth step was to install the poles to the ground, which was going to be quite a challenge

to do as the ground is very sandy. To counter that we created concrete stands using five-liter

bottle for alleight points of the archs, the idea was to make it anchor the poles to the ground

and assist sand to hold the tunnel down. After the poles were installed to the ground a larger

piece of the net was then used to cover the entire tunnel and sewed to the steel poles, and

then the twoY-standard were used to anchor the tunnel. After the tunnel was completed and

standing, we demonstrated the installation of drip irrigation, each seed bed had to have two

pipes and its own bucketwith sand in it whichact as a filter. It was emphasized that before

grey water is usedin the garden,wood ash must be applied to the water first and stored for a

week ortwo as woodash wouldneutralize the detergents on the water. The last step was

planting the vegetable seedling which were Chinese cabbage, mustard, Eggplant, spinach,

kale, onions, parsley, coriander and thyme.

33

Figure 10: Finishing off tunnel and installing drips

After the demonstration the hub staffwere confident on installing a micro-tunnel on their own,

however they will need a bit more practices to grasp the whole thing. The MDFteam will be

supervising the installation of other tunnels in the households of Enkovukeni.

Figure 26: YES interns having go at drips

34

Figure 27: A job well done in Enkovukeni

Field cropping demonstration workshops in Mabibi and Enkovukeni

Conservation Agriculture (No-Till) Demonstration

Following a climate change workshop

held atboth Enkovukeniand Mabibi, it

became clear to smallholder farmers that

it was time to adopt new methods to

ensure food production. Conservation

Agriculture (CA) emerged as one of the

most effective and reliable practices in

combating the effects of climate change

through soil conservation, moisture

retention through permanent soil cover on

and of season as well as growing soil

enriching crops. The purpose of the

workshop was to demonstrate the

principles of Conservation Agriculture,

also known as No-Till farming. The demonstration was conducted at the home of a smallholder

farmer, Bongiwe Manzini, atEnkovukeni and Mr Thwala at Mabibi.

Figure 28: CA planting demo atthe Manzini's

35

The first session of the day focused onexplaining the concept of(CA)and how minimum till

farming fits into this framework. CA involves agricultural practices that benefit both the soil and

the surrounding environment. These practices aim to improve both agricultural productivity

and environmental sustainability. CA plays a huge role in improving soil health and fertility

while encouraging soil cover throughout the seasons. According to community members,

monocropping of maize and cassava has been prevalent in the area, with cassava still being

a dominant staple monocrop today. However, CAstrongly discourages monocropping in

favourof mixed cropping, intercropping,

crop rotationand relay cropping. This

session was followed by a demonstration

of various seed crops that are compatible

with one another and can be rotated each

season.Summer Cover crops and Lucene

were new crops in the eyes of the farmers

in this area.

Next, we visited the demonstration site at

Bongiwe Manzini’s household. The plot

was 7 x 6 meters, and due to the small

size, the demonstration was set up in

strips. Each strip had two rows, resulting

in a total of 10 strips, each 6 meters in

length.

Demo Layout:

1.Maize

2.Beans

3.Sweet Corn (SCC)

4.Cowpeas

5.Lucerne

6.Maize

7.Beans

Potential Challenges

The farmers were excited about the new crops they saw and expressed interest in growing

more of them, particularly summer cover cropsand lucerne. However, they also voiced

concerns about several challenges. One major concern was the presence of monkeys and

hippos, which frequently interfere with crop production. Another challenge was the lack of rain,

which led to fearsthat the seeds planted could dry out before the rains arrived. To address

this, the farmers considered using micro-tunnels for planting field crops.

At the end of the demonstration, the farmers requested fencing for their "trial" plots, as they

believed it would help protect their crops from hippos, as for Monkeys they can try to guard

them from interference. The demonstration was a success, as the farmers were eager to try

planting the new seeds at their homes, despite the significant challenges they face. A total of

20 farmers were given seeds to plant, including maize, summercover crops, beans, cowpeas,

and lucerne.

Figure 29: Various seed participants took home to plant

their CA plots

36

In Mabibi,the demonstartion was one on plot with maize that poolry germinated with both the

communityand YES interns. Strips of maize, beans,SCC and cowpeas were done suing

manure at the base of the basins and tramlines. The group was eager to sow in seed to help

with rebuilding the soil. They volunttered to do their own plots as they had to clean them off

weeds first.

Figure 30: Snippets from the demonstration in Enkovukeni

Figure 31: CA demonstration in Mabibi at Mr Thwala's

37

Sokhulu field visit and CCA workshop report

Introduction

This report serves to give a summary of the main findings from the field visit to Sokhulu village

undertaken by MDF on the 4thof November which included walkabouts in four homesteads and a

discussion around their farming activities. The field visit was a fruitful one as it shed light on existing

activities, which helped identify pressing issues and possible solutions that peoplecould try out. The

visit was undertaken by Erna, Mazwi and Tema.

A variety of farming activities were observed during the walkabouts where farmers shared that they

were involved in both crop and livestock farming as well as small-scale forestry. Common crops

identified were maize, beans and a variety of vegetables. In terms of soil health, the households

reported challenges with soil fertility and erosion which affected their yields. Water access was

identified as a significant concern especially during dry spells. The farmers mainly depend on local

water holes and the municipal water tank which delivers free water twice a month. Observations also

revealed difficulties in managing pests and plant diseases, leading to uneven growth, and loss of yield.

Esther Mkhwanazi

Esther Mkhwanazo is a local farmer who farms individually and gets water from a local water hole.

She also does rainwater harvesting. Water is also delivered by the municipal watering truck twice a