WaterResearchCommission

Submitted to:

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Project team:

Mahlathini Development Foundaction(MDF)

Erna Kruger

Temakholo Mathebula

Betty Maimela

Nqe Dlamini

Institute of Natural Resources (INR)

Brigid Letty

Environmental and Rural Solutions (ERS)

Nickie McCleod, Sissie Mathela

Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD)

Derick du Toit

Project Number: C2022/2023-00746

Project Title: Dissemination and scaling of a decision support framework for CCA for smallholder

farmers in South Africa

Deliverable No.7: Case studies: Community based Climate Change Adaptationimplementation case studies

in 3 different agroecological zones in South Africa.

Date: 12August2024

Deliverable

7

2

Table of Contents

1.Introduction....................................................................................................................................4

2.Process planning and progress to date..........................................................................................6

Smallholder farmers in climate resilient agriculture learning groups............................................7

Communication and innovation...................................................................................................10

Multistakeholder platforms.........................................................................................................10

3.CbCCA Case Studies in 3 agroecological zones.............................................................................12

3.1Preamble.............................................................................................................................12

3.2Methodology.......................................................................................................................13

a.Introduction........................................................................................................................13

b.A theoretical foundation for assessing resilience of smallholder farming systems............14

c.Revision of the MDF resilience snapshot tool.....................................................................16

3.3MERL tools developed........................................................................................................23

3.4Agroecological zone climate resilience case studies...........................................................23

A.Mametja-Sekororo (Limpopo) climate resilience case study..............................................25

B.Bergville, KwaZulu -Natal case study..................................................................................35

3.5Development of a monitoring and evaluation platform and dashboard............................41

C.Matatiele, Eastern Cape case study....................................................................................41

3.6Conclusions.........................................................................................................................49

4.Exploration of factors that contribute towards greater success and sustainability of farming

business enterprises participating in the Mahlathini Development Foundation programmes: A case

study.....................................................................................................................................................49

4.1INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................49

4.2MAIN FEATURES OF A BUSINESS ENTERPRISE....................................................................51

4.3PROMOTION OF ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA.......................................51

4.4OVERVIEW OF FOCUSED SAVINGS GROUPS.......................................................................52

4.5THEORIES RELEVENT TO FARM-BASED MICROENTERPRISES..............................................54

4.5.2Resource-dependency Theory............................................................................................54

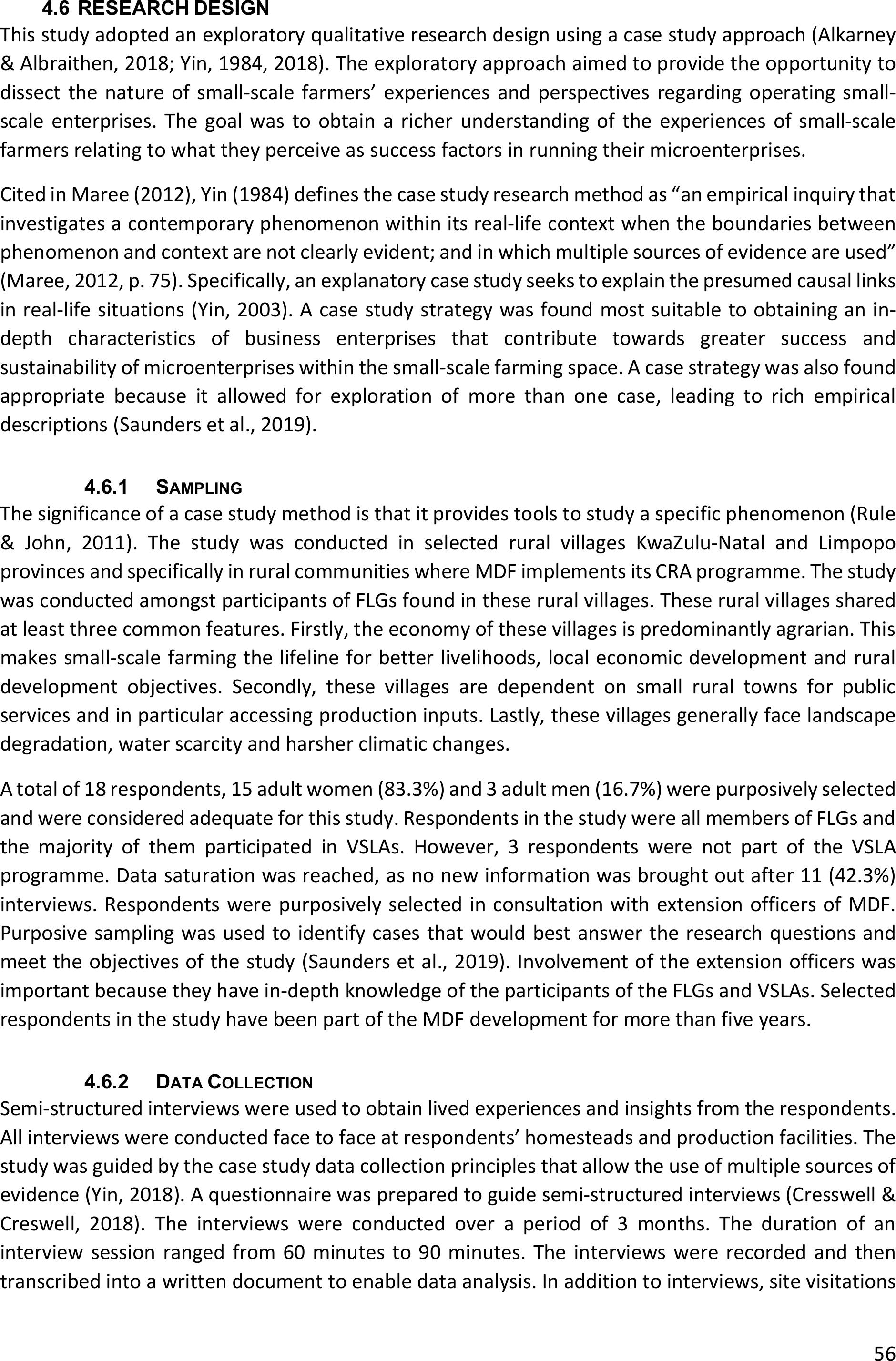

4.6RESEARCH DESIGN..............................................................................................................56

4.6.1Sampling..............................................................................................................................56

4.6.2Data Collection....................................................................................................................56

4.6.3Analysis...............................................................................................................................57

4.7RESULTS AND DISCUSSION..................................................................................................57

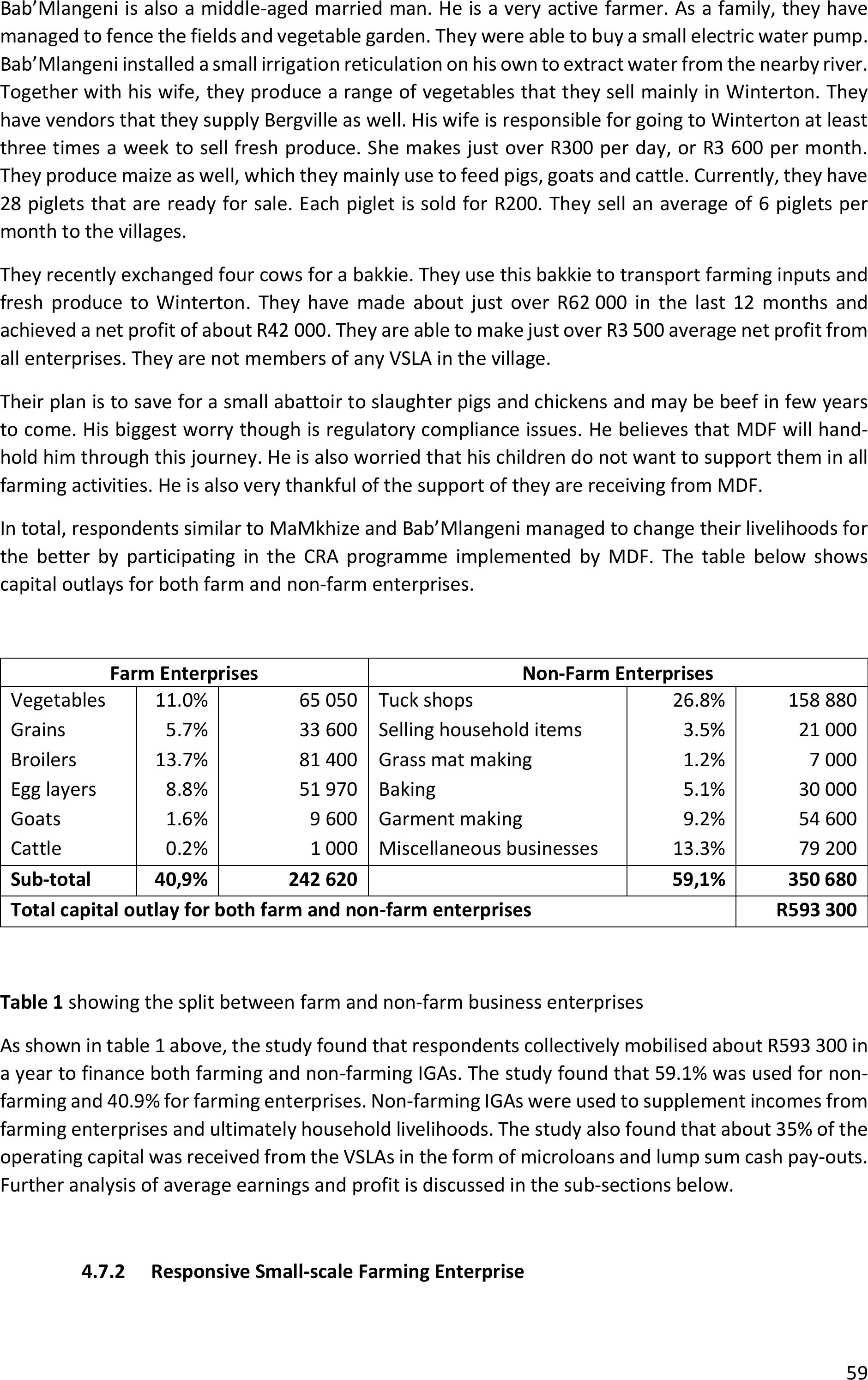

4.7.1Stories of Change................................................................................................................57

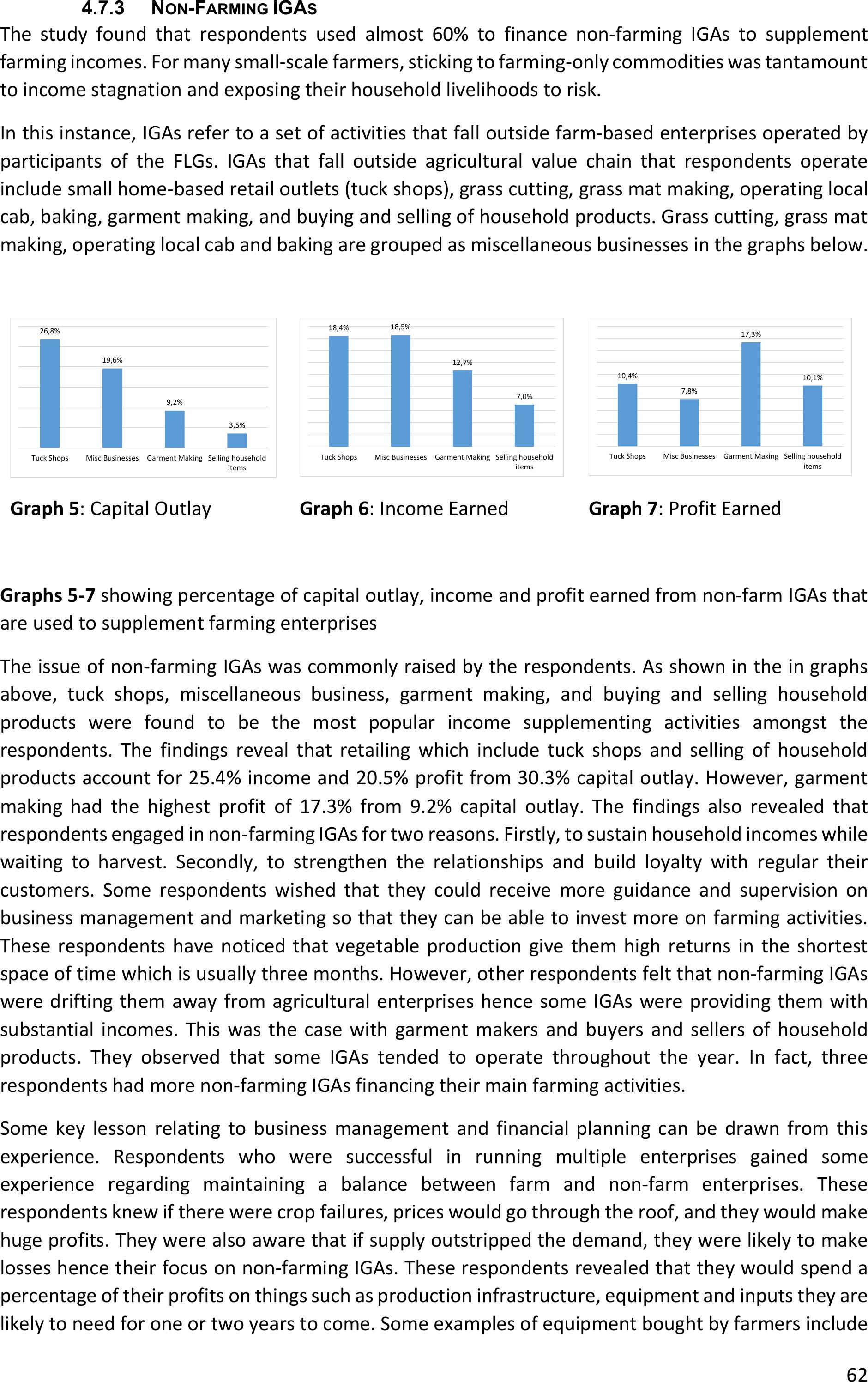

4.7.3Non-Farming IGAs...............................................................................................................62

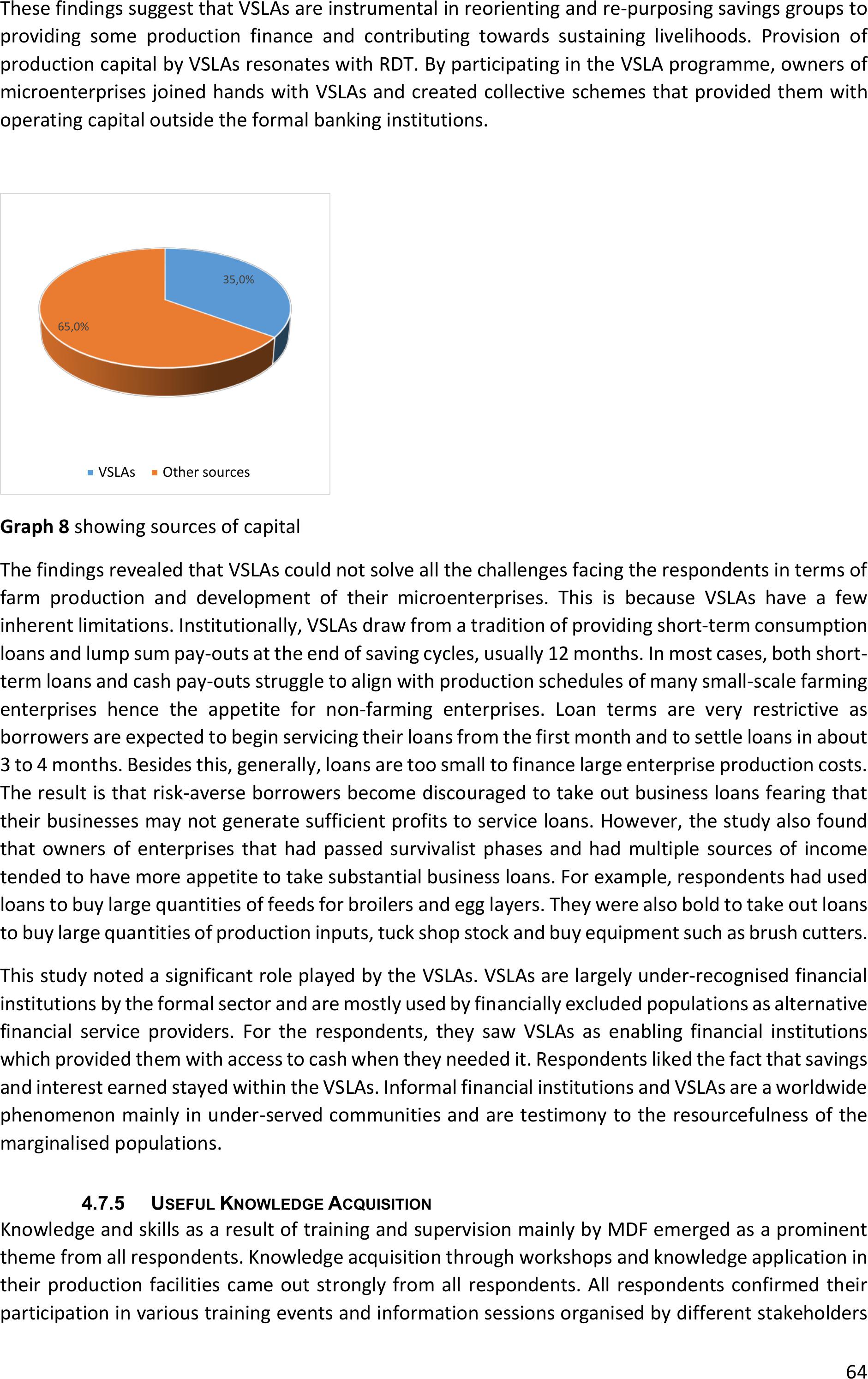

4.7.4VSLAs as Alternative Financial Resources...........................................................................63

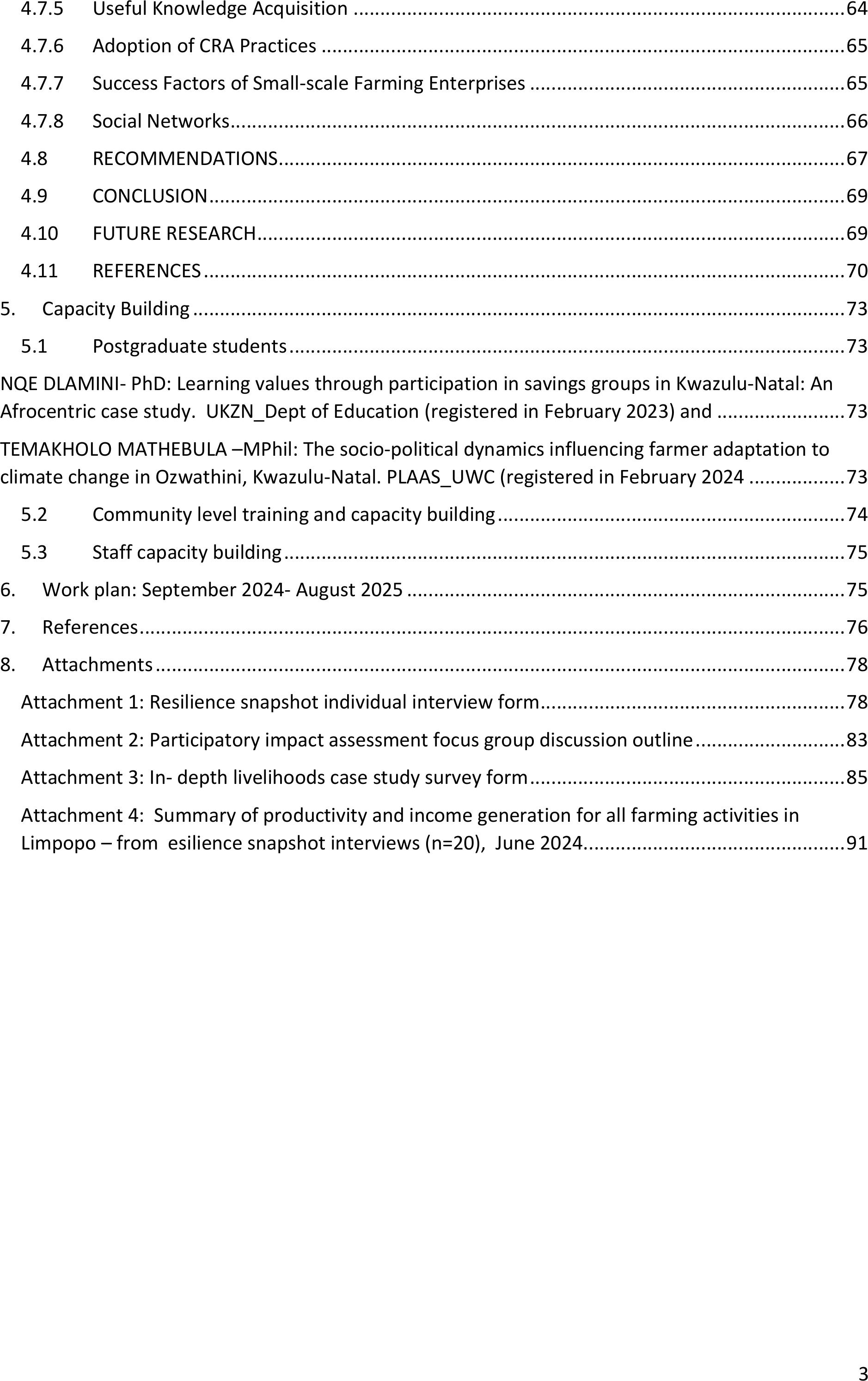

3

4.7.5Useful Knowledge Acquisition............................................................................................64

4.7.6Adoption of CRA Practices..................................................................................................65

4.7.7Success Factors of Small-scale Farming Enterprises...........................................................65

4.7.8Social Networks...................................................................................................................66

4.8RECOMMENDATIONS..........................................................................................................67

4.9CONCLUSION.......................................................................................................................69

4.10FUTURE RESEARCH..............................................................................................................69

4.11REFERENCES........................................................................................................................70

5.Capacity Building..........................................................................................................................73

5.1Postgraduate students........................................................................................................73

NQE DLAMINI- PhD: Learning values through participation in savings groups in Kwazulu-Natal: An

Afrocentric case study. UKZN_Dept of Education (registered in February 2023) and........................73

TEMAKHOLO MATHEBULA –MPhil: The socio-political dynamics influencing farmer adaptation to

climate change in Ozwathini, Kwazulu-Natal. PLAAS_UWC (registered in February 2024..................73

5.2Community level training and capacity building................................................................. 74

5.3Staff capacity building.........................................................................................................75

6.Work plan: September 2024- August 2025..................................................................................75

7.References....................................................................................................................................76

8.Attachments................................................................................................................................. 78

Attachment 1: Resilience snapshot individual interview form.........................................................78

Attachment 2: Participatory impact assessment focus group discussion outline............................83

Attachment 3: In- depth livelihoods case study survey form...........................................................85

Attachment 4: Summary of productivity and income generation for all farming activities in

Limpopo – from esilience snapshot interviews (n=20), June 2024.................................................91

4

1.INTRODUCTION

This section provides a brief summary of the project vision, outcomes and operational details.

OUTCOME

Vertical and horizontal integration of this community- based climate change adaptation (CbCCA)

model and process leads to improved water and environmental resources management, improved

rural livelihoods and improved climate resilience for smallholder farmers in communal tenure

areas of South Africa.

EXPECTED IMPACTS

1.Scaling out and scaling up of the CRA frameworks and implementation strategies lead to

greater resilience and food security for smallholder farmers intheir locality.

2.Incorporation of the smallholder decision support framework and CRA implementation into a

range of programmatic and institutional processes

3.Improved awareness and implementation of appropriate agricultural and water management

practices and CbCCA in a range of bioclimatic and institutional settings

4.Contribution of a robust CC resilience impact measurement tool for local, regional and

national monitoring processes.

5.Concrete examples and models for ownership and management of local group-based water

access and infrastructure.

AIMS

No

Aim

1.

Create and strengthen integrated institutional frameworks and mechanisms for

scaling up proven multi-benefit approaches that promote collective action and

coherent policies.

2.

Scaling up integrated approaches and practices in CbCCA.

3.

Monitoring and assessment of environmental benefits and agro-ecosystem

resilience.

4.

Improvement of water resource management and governance, including

community ownership and bottom-up approaches.

5.Chronology of activities

1.Desktop review of CbCCA policy and implementation presently undertaken in South

Africa

2.Set up CoPs:

a.Village based learning groups: A minimum of 1-3 LGs per province will be brought

on board.

b.Innovation platforms: 3 LG clusters, onefor each province consisting of a

minimum of 9- 36 LGs will be identified to engage coherently in this research and

dissemination process.

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Engage existing multistakeholder platforms such as

the uMzimvubu catchment partnership, SANBI- Living Catchments Programme,

the Adaptation Network, etc.

5

3.Develop roles and implementation parameters for each CoP

a.Village based learning groups: CCA learning and review cycles, farmer level

experimentation, CRA practices refinement, local food systems development,

water and resource conservation access and management and participation and

sharing in and across villages.

b.Innovation Platforms (IP): Clusters of LGs learn and share together with local and

regional stakeholders for knowledge mediation and co-creation and engagement

of Government Departments and officials (1-2 sessions annually for each IP)

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Developmentof CbCCA frameworks,

implementation processes (including for example linkages to IDPS and disaster

risk reduction planning and implementation at DM and LM level), reporting

frameworks for the NDC to the CCA strategy, consideration of models for

measurement of resilience and impact (1- 2 sessions annually for each multi

stakeholder platform)

4.Cyclical implementation for all three CoP levels (information provision and sharing,

analysis, action, and review) within the following thematic focus areas: Climate resilient

agriculture practices, smallholder microfinance options, local food systems and

marketingand community owned water and resources access and conservation

management plans and processes. Each ofthese thematic areas is to be led by one of the

senior researchers and a small sub-team.

5.Monitoring and evaluation: Consisting of the following broad actions:

a.Focus on 3-4 main quantitative indicators e.g. water productivity, production

yields, soil organic carbon and soil health.

b.Indicator development for resilience and impact and

c.Exploration of further useful models to develop an overarching framework.

6.Production of synthesis reports, handbooks and process manuals emanating from steps

1-4 withthe primary aim of dissemination of information.

7.And refinement of the CbCCA decision support platform, incorporating updated data sets

and further information form this research and dissemination process.

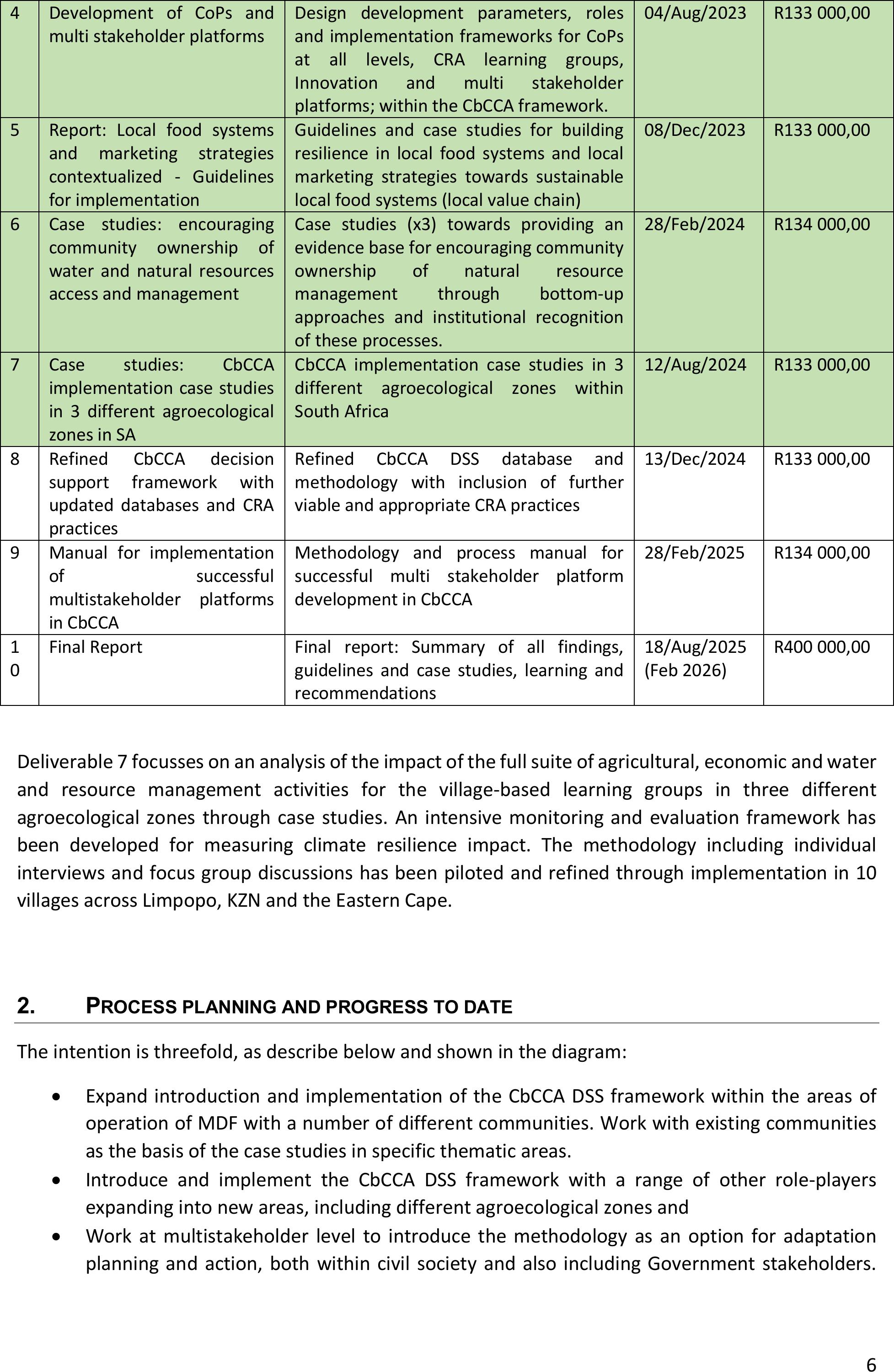

DELIVERABLES

N

o.

Deliverable Title

Description

Target Date

Amount

1

Desk top review for CbCCA in

South Africa

Desk top review of South African policy,

implementation frameworks and

stakeholder platforms for CCA.

01/Aug/2022

R100 000,00

2

Report: Monitoring

framework, ratified by

multiple stakeholders

Exploration of appropriate monitoring

tools to suite the contextual needs for

evidence-based planning and

implementation.

02/Dec/2022

R100 000,00

3

Handbook on scenarios and

options for successful

smallholder financial services

within the South Africa

Summarize VSLA interventions in SA, Govt

and Non-Govt and design best bet

implementation process for smallholder

microfinance options.

28/Feb/2022

R100000,00

6

4

Development of CoPs and

multi stakeholder platforms

Design development parameters, roles

and implementation frameworks for CoPs

at all levels, CRA learning groups,

Innovation and multi stakeholder

platforms; within the CbCCA framework.

04/Aug/2023

R133000,00

5

Report: Local food systems

and marketing strategies

contextualized - Guidelines

for implementation

Guidelines and case studies for building

resilience in local food systems and local

marketingstrategies towards sustainable

local food systems (local value chain)

08/Dec/2023

R133000,00

6

Case studies: encouraging

community ownership of

water and natural resources

access and management

Case studies (x3) towardsproviding an

evidence base for encouraging community

ownership of natural resource

management through bottom-up

approaches and institutional recognition

of these processes.

28/Feb/2024

R134000,00

7

Case studies: CbCCA

implementation case studies

in 3 different agroecological

zones in SA

CbCCA implementation case studies in 3

different agroecological zones within

South Africa

12/Aug/2024

R133000,00

8

Refined CbCCAdecision

support framework with

updated databases and CRA

practices

Refined CbCCA DSS database and

methodology with inclusion of further

viable and appropriate CRA practices

13/Dec/2024

R133000,00

9

Manual for implementation

of successful

multistakeholder platforms

in CbCCA

Methodology and process manual for

successful multi stakeholder platform

development in CbCCA

28/Feb/2025

R134000,00

1

0

Final Report

Final report: Summary of all findings,

guidelines and case studies, learning and

recommendations

18/Aug/2025

(Feb 2026)

R400000,00

Deliverable7 focusses on an analysis of the impact of the full suite of agricultural, economic and water

and resource management activities for the village-based learning groups in three different

agroecological zones through case studies. An intensive monitoring and evaluation framework has

been developed for measuring climate resilience impact. The methodology including individual

interviews and focus group discussions has been piloted and refined through implementation in 10

villages across Limpopo, KZN and the Eastern Cape.

2.PROCESS PLANNING AND PROGRESS TO DATE

The intention is threefold, as describe below and shown in the diagram:

•Expand introduction and implementation of the CbCCA DSS framework within the areas of

operation of MDFwith a number of different communities. Work with existing communities

as the basis of the case studies in specific thematic areas.

•Introduce and implement the CbCCA DSS framework with a range of other role-players

expanding into new areas, including different agroecological zones and

•Work at multistakeholder level to introduce the methodology as an option for adaptation

planning and action, both within civil society and also including Government stakeholders.

7

This is the first step towards institutionalization of the processand will involve mainly working

within existing multistakeholder platforms and networks as the starting point.

•Further exploration of the categories of stakeholders and the roles and relationships between

stakeholders is important for the present research brief.

Figure 1: Conceptualization of stakeholder platforms at multiple levels to support CbCCA

Smallholder farmers in climate resilient agriculturelearning groups

This process has been initiatedby continuing and strengthening specificCRA learning groups,which

have been supported by MDF in the past and whohave done well in implementation and building of

social agency. These groups will provide the focus for further exploration of food systems, water

stewardship and governance and engagement with local and district municipalities.

CRA learning group summary:

Province

Area

Villages

No of participants

KZN

Bergville

Ezibomvini, Stulwane, Vimbukahlo, Eqeleni, Emadakaneni

130

Midlands

Ozwathini, Gobizembe, Mayizekanye, Ndlaveleni

110

SKZN

Mahhehle,Mariathal, Centocow, , Ngongonini

90

Limpopo

Sekororo-Lestitele

Sedawa, Turkey,Willows, Santeng, Worcester, Madeira

110

EC

Matatiele

Ned, Nchodu, Nkau, Rashule,

75

5

23

515

Table 1: Micro-level CoP engagement: February 2023to August2024

Note: Collaborative strategies in bold undertaken during this reporting period

Description

Date

Activity

Establishing learning groups at

village level

2022/11/25, 12/09

2022/11/15, 11/29,

2023/02/07

Limpopo: Sophaya

SKZN: Mahhehle -CCA workshop x 2 days,

Innovation and multistakeholder platforms-

MESO AND MACRO

Communication and innovation

-MESO

Smallholder farmers in CRA learning groups

(LGs)

-MICRO

•National Networks e.g. Adaptation

network, Agroecology Network

•National organistions e.g., PGS-SA and

SAOSO

•Regional forums e.g., Water Source

Areas forums (WWF) Living

catchments Forums (SANBI)

•Cluster of LGs within and between

areas learn and implement CRA

together

•These clusters ineteract with external

stakeholders e.g., NGOs, Government

Deparments, Local and District

Municipalities, traditional authorities

and Water Service authorities

•Individual farmers in LGs learn and

implement CRA together

•LG's set up other interest groups and

committees e.g., water committees,

viallge savings and loan assocations,

marketing groups, livestock associations

and resource conservaiotn agreements

8

2023/02/09

2023/01/18

2023/03/27

2023/06/15, 07/07

Bergville: Eqeleni

EC: Ned, Nkau

Limpopo: Madeira

KZN Midlands: Ndlaveleni, Montobello, Noodsberg, Inkuleleko primary

school

Training and mentoring for

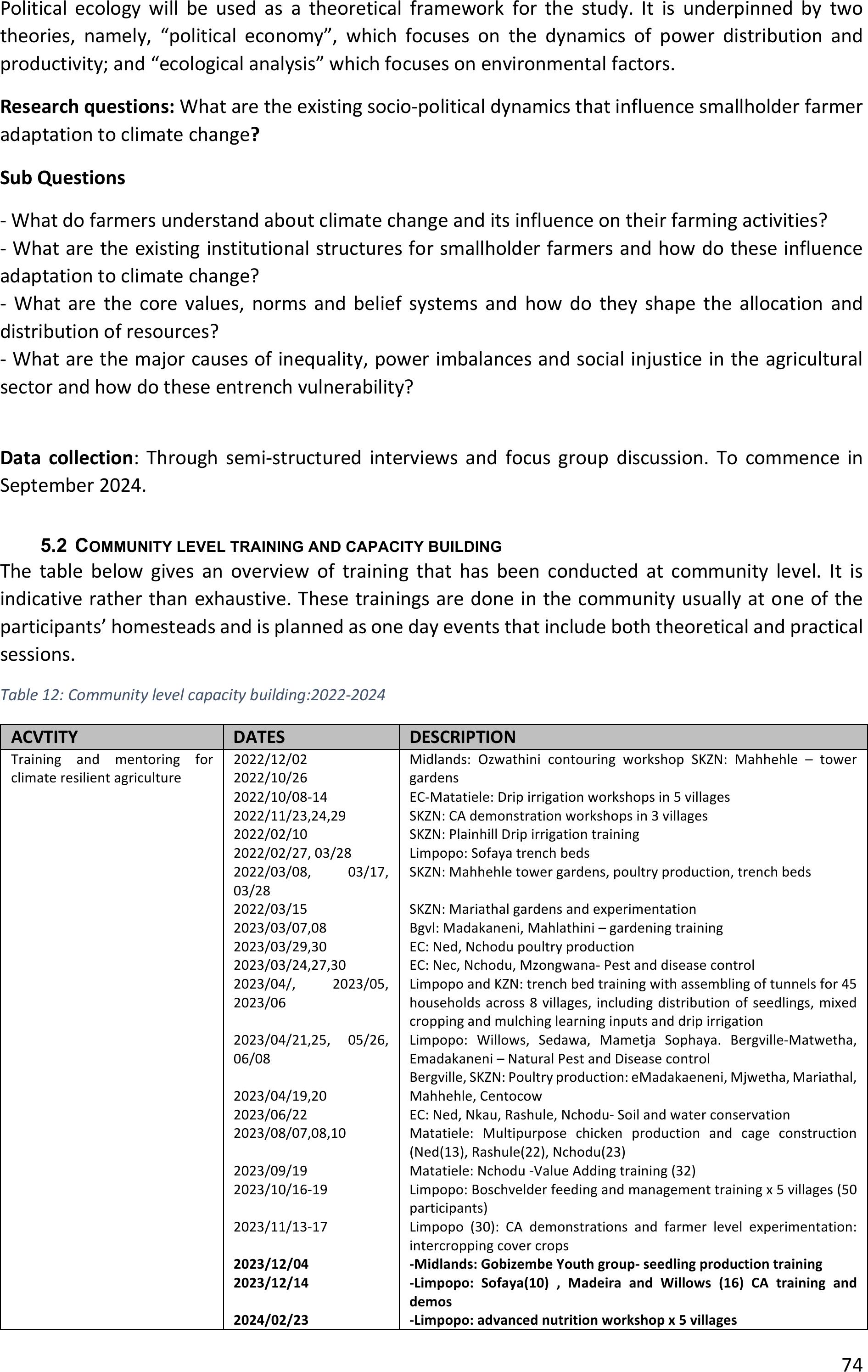

climate resilient agriculture

2022/12/02

2022/10/26

2022/10/08-14

2022/11/23,24,29

2022/02/10

2022/02/27, 03/28

2022/03/08, 03/17,

03/28

2022/03/15

2023/03/07,08

2023/03/29,30

2023/03/24,27,30

2023/04/, 2023/05,

2023/06

2023/04/21,25, 05/26,

06/08

2023/04/19,20

2023/06/22

2023/08/07,08,10

2023/09/19

2023/10/16-19

2023/11/13-17

2023/12/04

2023/12/14

2024/02/23

2024/03/22

2024/05/28

Midlands: Ozwathinicontouring workshop SKZN: Mahhehle – tower

gardens

EC-Matatiele: Drip irrigation workshops in 5 villages

SKZN: CA demonstration workshops in 3 villages

SKZN: Plainhill Drip irrigation training

Limpopo: Sofaya trench beds

SKZN: Mahhehle tower gardens, poultry production, trench beds

SKZN: Mariathal gardens and experimentation

Bgvl: Madakaneni, Mahlathini– gardening training

EC: Ned, Nchodu poultry production

EC: Nec, Nchodu, Mzongwana- Pest and disease control

Limpopo and KZN: trench bed training with assembling of tunnels for 45

households across 8 villages, including distribution of seedlings, mixed

cropping and mulching learning inputs and drip irrigation

Limpopo: Willows, Sedawa, MametjaSophaya. Bergville-Matwetha,

Emadakaneni – Natural Pest and Disease control

Bergville, SKZN: Poultry production: eMadakaeneni, Mjwetha, Mariathal,

Mahhehle,Centocow

EC: Ned, Nkau, Rashule, Nchodu- Soil and water conservation

Matatiele: Multipurposechicken production and cage construction

(Ned(13), Rashule(22), Nchodu(23)

Matatiele: Nchodu -Value Adding training (32)

Limpopo: Boschvelder feeding and management training x 5 villages (50

participants)

Limpopo (30): CA demonstrations and farmer level experimentation:

intercropping cover crops

-Midlands: Gobizembe Youth group- seedling production training

-Limpopo: Sofaya(10) , Madeira and Willows (16) CA training and

demos

-Limpopo: advanced nutrition workshop x 5 villages

-SKZN: gardening refresher workshops (Centocow, Mahhehle,

Mariathal, Ngongonini)

-Matatiele (EC) nutrition workshops x 4 villages

Cyclical implementation through

mentoring for capacity

development for LG at local level

2022/08/16,17,18,19,30

2022/10/16

2022/11/21-24

2023/01/24-30

ONGOING

2023/10/03-06

2023/11/05-12/15

2023/11/30-2024/02/28

2024/ 03/ 30

2024/07/08

CCA review and planning workshops

-Bergville: CA review and planning (5)

-Midlands: CA review and planning (3)

-Limpopo: CCA review and planning (4)

CCA prioritization of practices

-Matatiele: 5 villages (Ned, Nchodu, Rahsule, Nkau, Mzongwana

-All areas: garden monitoring, poultry support,tunnel and drip kit

installations,VSLAs monthly meetings, CA production and monitoring

KZN-Bergville Boschvelderchicken delivery and maintenance mentoring

for 45 participants

KZN: Bergville_CA farmer experimentationplanting for 124 participants,

incl cover cropsawa collaboration with Forge Agri to Fodder Beet trials

and Zylem SA for new Maize variety trials

Midlands:Seedling nursery project initiation for youth group in

Gobizembe (11 members)

-KZN,EC and Limpopo – 2ndround micro tunnelintroduction and

deliveries (x30 tunnels)

-KZN ,EC and Limpopo- 2ndround of multipurpose chicken delivery,

training and mentoring, including introduction of incubators for local

breeding

Income diversification and

economic empowerment of

local farmers (LG at local level)

Ongoing - Monthly

Jan-December2023

July-Sept 2023

Market days: monthly farmers markets

-Midlands: Bamshela (Ozwathini)

-SKZN: Creighton (Centocow)

-Ubuhlebezwe LED Ixopo flea market

- Bergville: Bergville town

Market exploration workshops

-Midlands: Mayizekanye, Gobizembe

-EC_Ned-Nchodu market day in Matatiele

-SKZN: Mariathal

PGS follow-up w/s Limpopo

SKZN: Mahhehle

9

Ongoing- Monthly

April-June 2024

May-July 2024

VSLA meetings and share outs

-Bergville (18)

-SKZN: Ngongonini (2), Centocow (4)

-Midlands: Ozwathini (6)

Limpopo: (7)

-Youth Dialogues – Limpopo (Sedawa, Turkey, Willows, Madeira)

-Income diversificationindividual interviews - all areas(x15)

Implementation and capacity

development for innovation (3)

and multi-stakeholder platforms

(3)

2022/11/18

2022/11/10

2022/12/01

2023/02/23

2023/02/28

2023/03/08,09

2023/03/89,29,

May-July 2023

2023/03/30, 06/02

2023/04/26

2023/05/09

2023/07/10-15

2023/08/18

2023/08/29

2023/08/30

2023/09/04

2023/09/08

2023/09/13

2023/09/22-24

2023/08/23, and 09/27

2023/07-12

2024/03/12,20

-SKZN: CentocowP&D control cross visit and learning workshop

-uThukela water source forum: Visioning and action planning – Bergville

-Adaptation Network AGM

-Regenerative Agric farmers’ day in Bergville incl Asset research,

uThukela Water Source Forum, uThukela Development Agency

-Adaptation Network: CCA financing dialogue

-SANBI_gender mainstreaming dialogue

-WRC-ESS: Bglv Ezibomvini, Stulwane –resource management mapping

and planning

Bergillve:Stulwnaeweekly community resource management workdays

-Okahlamba LED forum

-Farmers X visit between Bulwer (supported by the INR0 and Bergville

around CRA, fodder and restoration

-PGS-SA: market training input: Online training Session 5

-Giyani Local Scale Climate resilience Project: Introduction of CCA model

and local water governance options.

-World Vision: CCA workshops for women cooperatives and LED project

(60 participants)

-Giyani Climate resilience project: Input into WRC reference group

meeting

-KZN DARD_ Okahlamba Agricultural Show: display and talk

ACDI: Dialogue on community adaptation and resilience (Stellenbosch)

Food systems article for newsletter

WWF-Business Network meeting (SAPPI Durban)- presentation

Joint Bergville learning group local marketing review session

Gcumisa_multistakeholder innovation meeting – with the INR, ~60

participants (value adding, stokvels and local marketing

Food systems dialogue: online event

Uthukela water source forum: Core team meeting and Multistakeholder

field visit around community resource conservation in Stulwane (Bgvl)

-LIMA -Social Employment Fund: Training for work teams and employed

youth in nutrition, value adding, climate change adaptation and

agroecological gardening practices including soil and water conservation

in 7 areas: Zululand, SKZN, Lichtenburg, Sekororo,Musina and Blouberg

(140 participants trained).

Northern Drakensberg collaborative multistakeholder meeting in

Bergville (55 participants)

Indicator development for

evidence-based indicators, M&E

and handbook development

2023/01/30- 02/03

2023/02/02

2023/01/18

2023/01/18

2023/02/20

March-May 2023

June 2023

2023/10/16-20, 11/13-

16

2024/02/26

May-July 2024

31/05/2024, 07, 12, 18

/07/2024

Limpopo: Focus Group discussions for VSLA and microfinance for the

rural poor x 3 (Turkey, Worcester, Santeng)

Garden monitoring:

-SKZN: Plainhill

-EC: 5 villages

CA monitoring

-EC:5 villages

-KZN: Bergville -30, Midlands 15, SKZN 15

-All areas: Poultry production list

-All areas: Livelihoods survey for farmgate sales and asset accumulation

-M&E resilience indicatordevelopment team meeting and process with

KarenKotschy

-Design of framework

-Development of individual interviews and Participatory impact

assessment outlines for testing. Interviewing of 120 participants across

KZN,EC and Limpopo and running of 10 PIA workshops

- Initiate development of analysis platform and dashboards for Climate

resilience impact assessments

Implementation of sustainable

water management

2023/01/03-02/03

2023/03/07

2023/03/25, 06/15

2023/04/25, 06/01,02,

06/14.

KZN: Bergville: Stulwane– Conflict man and upgrading spring protection.

EC: Nkau: Water walk and meetings for spring protection and

reticulation.

KZN: Bgvl Stulwane_ Engineer visits (Alain Marechal) for scenario

development and follow up planning meetings with community. Set up

committee, work parties and start on quotes and budget outline

10

2023/07/26-28,

09/14,10/09-14, 11/06-

10, 12/05-15,

2024/01/21-02/02

KZN: Bgvl Vimbukhalo: Governance of communal borehole water supply

KZN: Bgvl Stulwane_ Engineer visits (Alain Marechal) for scenario

development and follow up planning meetings with community. Set up

committee, work parties and start on quotes and budget outline. Work

on scheme initiated.Final implementation of scheme.

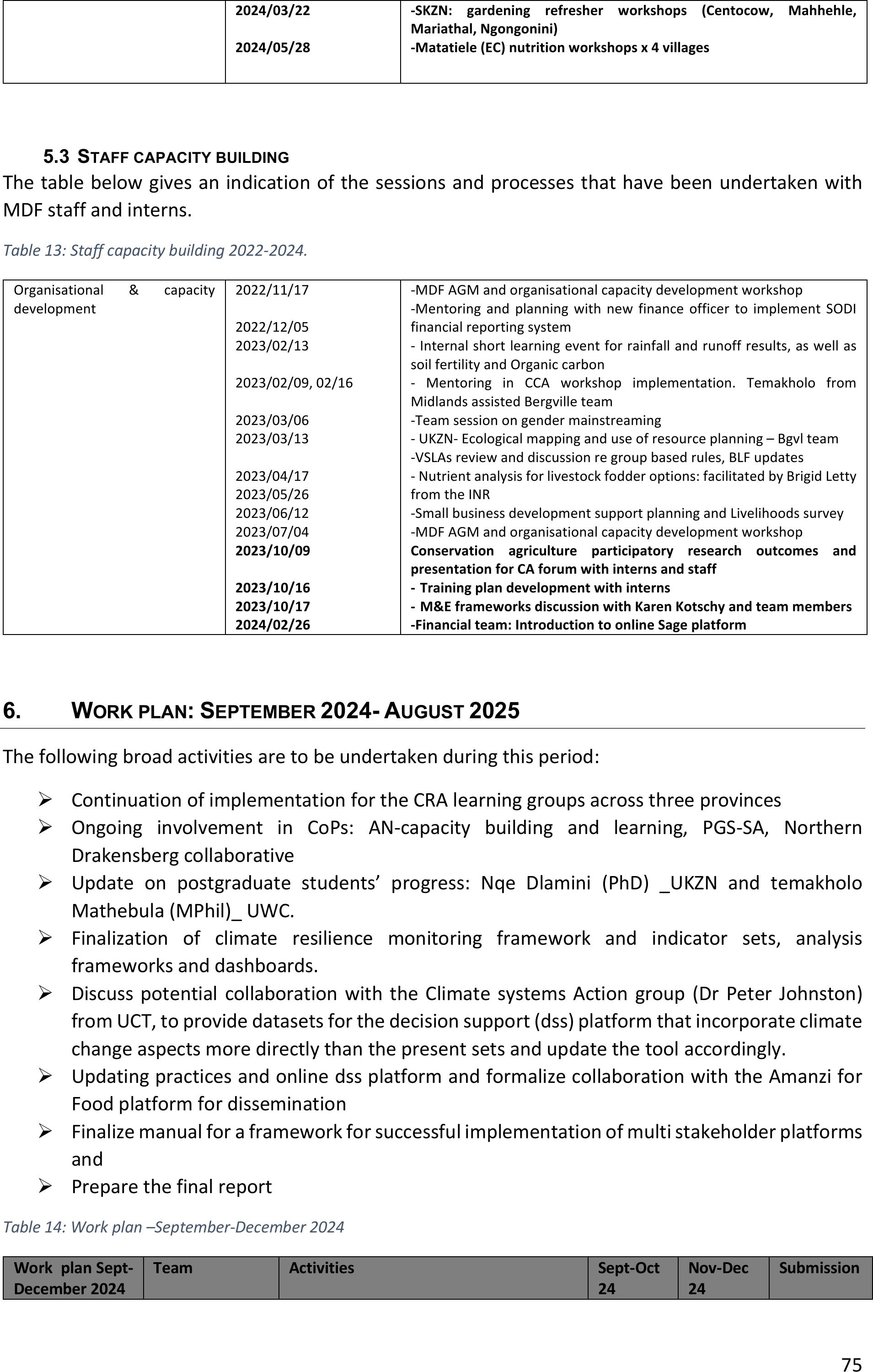

Organisational& capacity

development

2022/11/17

2022/12/05

2023/02/13

2023/02/09, 02/16

2023/03/06

2023/03/13

2023/04/17

2023/05/26

2023/06/12

2023/07/04

2023/10/09

2023/10/16

2023/10/17

2024/02/26

-MDF AGM and organisational capacity development workshop

-Mentoringand planning with new finance officer to implement SODI

financial reporting system

- Internal short learning event for rainfall and runoff results, as well as

soil fertility and Organic carbon

- Mentoring in CCA workshop implementation. Temakholo from

Midlands assisted Bergville team

-Team session on gender mainstreaming

- UKZN- Ecological mapping and use of resource planning – Bgvl team

-VSLAs review and discussion re group based rules, BLF updates

- Nutrient analysis for livestock fodder options: facilitated by Brigid Letty

from the INR

-Small business development support planning and Livelihoods survey

-MDF AGM and organisational capacity development workshop

Conservation agriculture participatory research outcomes and

presentation for CA forum with interns and staff

-Training plan development with interns

-M&E frameworks discussion with Karen Kotschy and team members

-Financial team: Introduction to online Sage platform

Communication and innovation

This aspect relates to platforms for sharing and learning with clusters of learning groups (LGs). No

activities were undertaken here between March and July2024.

Multistakeholder platforms

To date the research team has participated in a range multistakeholder platforms, networks and

communities of practices (CoPs) towards developing a framework for awareness raising,

dissemination and incorporation of the CbCCA-DSS methodology into local andregional planning

processesand developing methodological coherence for a number of the themes to be explored in

this brief.

The table below outlines actions and meetings to date.

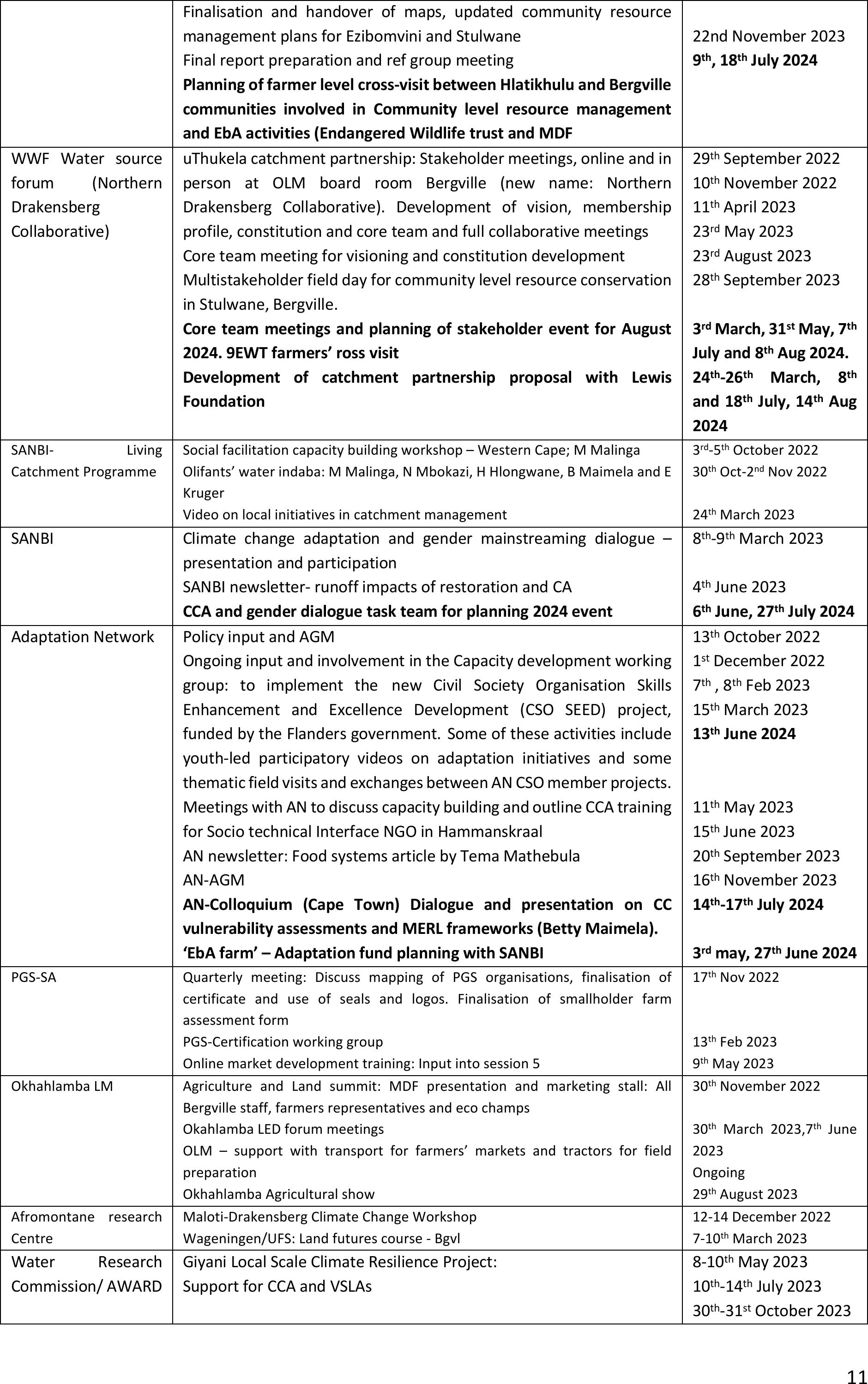

Table 2: Planning and multi stakeholder interactions for the CCA-DSSII research process: August2024

Organisation

Activity - Description

Dates

Asset Research-

Maize Trust, SODI

Regenerative Agriculture farmers’ open day in Bergville

Annual Maize Trust CA forum workshop,Bethlehem – MDF

presentation

9thWorld Conference in Conservation Agriculture (Cape Town).

Presentation of 3 papers (E kruger, T Mathebula and N Mbokazi and

Smallholder farmers panel member.

23rdFeb 2023

10thOctober 2023

23rd-26thJuly 2024

Zylem and Regen-Z

(sustainable

agriculture

company-KZN)

Collaboration in farmer level experimentation with application of

liquid supplements for soil health and testing of 10 varieties of

climate adapted maize with 10 farmers in Bergville, KZN. Planning

for 2ndround of experimentationand distribution of input packs to

smallholder farmers

December 2023-May

2024

9thJuly 2024

ESS research - WRC

UKZN research in ecosystem services mapping supported by MDF:

water walks, focus group discussions, planning, eco-champs, spring

protection work in Stulwane, thematic and mapping workshops in

Ezibomvini and Stulwane, local level planning and implementation.

Cross visit Ezibomvini to Stulwane to see resource management work

23rdSeptember 2022

14thOctober 2022

13,29,30 March 2023

1-30thMay 2023

29th September 2023

18th October 2023

11

Finalisation and handover of maps, updated community resource

management plans for Ezibomvini and Stulwane

Final report preparation and ref group meeting

Planning of farmer level cross-visit between Hlatikhulu and Bergville

communities involved in Community level resource management

and EbA activities (Endangered Wildlife trust and MDF

22nd November 2023

9th, 18thJuly 2024

WWF Water source

forum(Northern

Drakensberg

Collaborative)

uThukela catchment partnership: Stakeholder meetings, online and in

person at OLM board room Bergville (new name: Northern

Drakensberg Collaborative). Development ofvision, membership

profile, constitution and core team and full collaborative meetings

Core team meeting for visioning and constitution development

Multistakeholder field day for community level resource conservation

in Stulwane, Bergville.

Core team meetings and planning of stakeholder event for August

2024.9EWT farmers’ ross visit

Development of catchment partnership proposal with Lewis

Foundation

29thSeptember 2022

10thNovember 2022

11thApril 2023

23rdMay 2023

23rdAugust 2023

28thSeptember 2023

3rdMarch, 31stMay, 7th

July and 8thAug 2024.

24th-26thMarch, 8th

and 18thJuly, 14thAug

2024

SANBI- Living

Catchment Programme

Social facilitation capacity building workshop – Western Cape; M Malinga

Olifants’ water indaba: M Malinga, N Mbokazi, H Hlongwane, B Maimela and E

Kruger

Video on local initiatives in catchment management

3rd-5thOctober 2022

30thOct-2ndNov 2022

24thMarch 2023

SANBI

Climate change adaptation and gender mainstreaming dialogue –

presentation and participation

SANBI newsletter- runoff impacts of restoration and CA

CCA and gender dialogue task team for planning 2024 event

8th-9thMarch 2023

4thJune 2023

6thJune, 27thJuly 2024

Adaptation Network

Policy input and AGM

Ongoing input and involvement in the Capacity development working

group: to implement thenew Civil Society OrganisationSkills

Enhancement and Excellence Development (CSO SEED) project,

funded by the Flanders government.Some of these activities include

youth-led participatory videos on adaptation initiatives and some

thematic field visits and exchanges between AN CSO member projects.

Meetings with AN to discuss capacity building and outline CCA training

for Socio technical Interface NGO in Hammanskraal

AN newsletter: Food systems article by Tema Mathebula

AN-AGM

AN-Colloquium (Cape Town) Dialogue and presentation on CC

vulnerability assessments and MERL frameworks (Betty Maimela).

‘EbA farm’ – Adaptation fund planning with SANBI

13thOctober 2022

1stDecember 2022

7th, 8thFeb 2023

15thMarch 2023

13thJune 2024

11thMay 2023

15thJune 2023

20thSeptember 2023

16thNovember 2023

14th-17thJuly 2024

3rdmay, 27thJune 2024

PGS-SA

Quarterly meeting: Discuss mapping of PGS organisations, finalisation of

certificate and use of seals and logos. Finalisation of smallholder farm

assessment form

PGS-Certification working group

Online market development training: Input into session 5

17thNov 2022

13thFeb 2023

9thMay 2023

Okhahlamba LM

Agriculture and Land summit: MDF presentation and marketing stall: All

Bergville staff, farmers representatives and eco champs

Okahlamba LED forum meetings

OLM – support with transport for farmers’ markets and tractors for field

preparation

Okhahlamba Agricultural show

30thNovember 2022

30thMarch 2023,7thJune

2023

Ongoing

29thAugust 2023

Afromontane research

Centre

Maloti-Drakensberg Climate Change Workshop

Wageningen/UFS: Land futures course - Bgvl

12-14 December 2022

7-10thMarch 2023

Water Research

Commission/ AWARD

Giyani Local Scale Climate Resilience Project:

Support for CCA and VSLAs

8-10thMay 2023

10th-14thJuly 2023

30th-31stOctober 2023

12

3.CBCCACASE STUDIES IN 3AGROECOLOGICAL ZONES

By Nqe Dlamini, Erna Kruger, Betty Maimela,Temakholo Mathebula, Hlengiwe Hlongwane, Nqobile

Mbokazi, Siphumelelo Mbheleand Anna and Karen Kotschy.

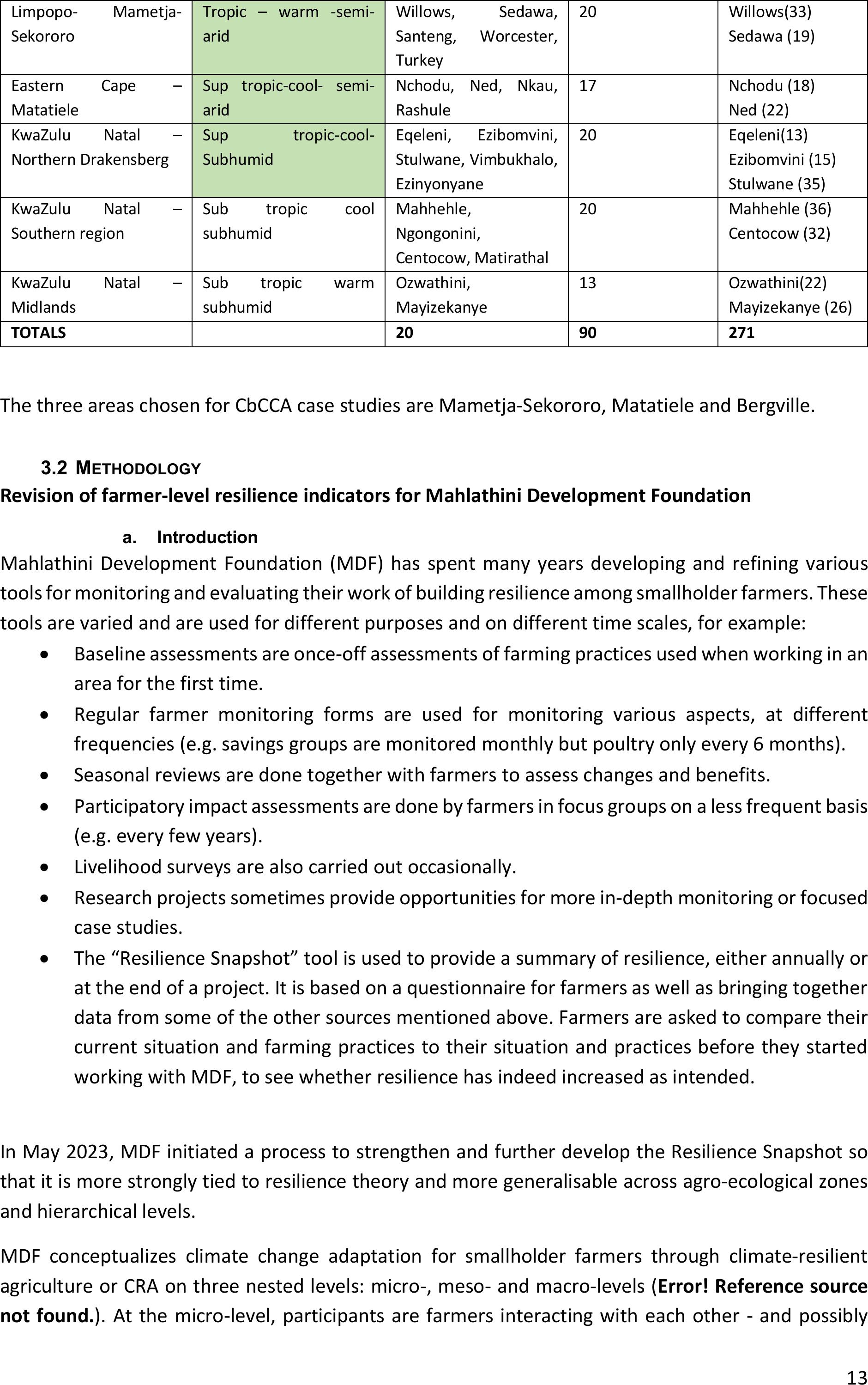

3.1PREAMBLE

To enable the compilation of case studies in community based climate change adaptation (CbCCA) the

monitoring and evaluation framework developedin the WRC project entitled Climate change

adaptation for smallholder farmer in South Africa,(WRC K5-2179-4)(Kruger, 2021), has been reviewed

and updated to allow for greater methodological coherence and improved measurability of the

climate resilient indicator sets outlined.

The resultant framework was used to design individual interviews (resilience snapshots) and a

participatory impact assessment outline for focus group discussions, emphasising the human, social

and governance aspects of the process.

The following interviews and PIA workshops were undertaken between May and July 2024

Table 3: CbCCA interviews and focus groups undertaken in different agroecological zones.

Province/area

Agroecological zone

(HarvestChoice;

International Food

Policy Research Institute

(IFPRI), 2015)

Villages

Number of

individual

Interviews

PIAs(focus group

discussions)

Water governance and infrastructure management community

dialoguein Mayephu, Giyani – for development of guidelines and

proof of concept

WRC- ref grp meetings for: Enterprise development and innovation for

rural water schemes- GLSCRP

3rdand 29thNovember

2023, 24thJune,3rdJuly

2024

Umzimvubu

Catchment

Partnershipand ERS–

Nicky McCleod, Sissie

Mathela

Webinar toreview CRAand spring protection implementation and

plan for future projects

Planning for combined spring protection in Nkau and next deliverable

Multi stakeholder governance inputs

8thNov 2022

15thJune 2023

2ndAugust 2023

AWARD – Derick du

Toit

Meeting in Hoedspruit to discuss AWARD’s contribution

Youth induction programme– Tala Table network

Planning for CRA learning group expansion, Mametja-Sekororo PGS

continuation.

Group marketing review and farm level assessments

Youth dialogues in 5 villages. Outline for proposal to DKA

2ndNovember 2022

30thJanuary 2023

22ndMarch 2023

8thMay 2023,

29thSeptember 2023

April-July 2024

Karen Kotshcy

Learning in M&E interest group meeting. Discussions re methodology

for UCP and Tsitsa project multi stakeholder engagement evaluation

Discussions and MoU development for M&E framework and indicator

developmentand submission of report for WRC deliverable 4.

Development of Climate resilient indicators for CbCCA

11thNovember 2022

15thMay 2023

24thMay 2023

16-20thOctober, 13th-

16thNovember2023

8thand 19thFebruary

2024, 27thJune, 8thand

12thJuly 2024

13

Limpopo- Mametja-

Sekororo

Tropic – warm -semi-

arid

Willows, Sedawa,

Santeng, Worcester,

Turkey

20

Willows(33)

Sedawa(19)

Eastern Cape –

Matatiele

Sup tropic-cool- semi-

arid

Nchodu, Ned, Nkau,

Rashule

17

Nchodu(18)

Ned(22)

KwaZulu Natal–

Northern Drakensberg

Sup tropic-cool-

Subhumid

Eqeleni, Ezibomvini,

Stulwane, Vimbukhalo,

Ezinyonyane

20

Eqeleni(13)

Ezibomvini(15)

Stulwane(35)

KwaZulu Natal–

Southern region

Sub tropic cool

subhumid

Mahhehle,

Ngongonini,

Centocow, Matirathal

20

Mahhehle(36)

Centocow (32)

KwaZulu Natal–

Midlands

Sub tropic warm

subhumid

Ozwathini,

Mayizekanye

13

Ozwathini(22)

Mayizekanye(26)

TOTALS

20

90

271

The three areas chosen for CbCCA case studies are Mametja-Sekororo, Matatiele and Bergville.

3.2METHODOLOGY

Revision of farmer-level resilience indicators for Mahlathini Development Foundation

a.Introduction

MahlathiniDevelopment Foundation (MDF) has spent many years developing and refining various

tools for monitoring and evaluating their work of building resilience among smallholder farmers. These

tools are varied and are used for different purposes and on different time scales, for example:

•Baseline assessments are once-off assessments of farming practices used when working in an

area for the first time.

•Regular farmer monitoring forms are used for monitoring various aspects, at different

frequencies (e.g. savings groups are monitored monthly but poultry only every 6 months).

•Seasonal reviews are done together with farmers to assess changes and benefits.

•Participatory impact assessments are done by farmers in focus groups on a less frequent basis

(e.g. every few years).

•Livelihood surveys are also carried out occasionally.

•Research projects sometimes provide opportunities for more in-depth monitoring or focused

case studies.

•The “Resilience Snapshot” tool is used to provide a summary of resilience, either annually or

at the end of a project. It is based on a questionnaire for farmers as well as bringing together

data from some of the other sources mentioned above. Farmers are asked to compare their

current situation and farming practices to their situation and practices before they started

working with MDF, to see whether resilience has indeed increased as intended.

In May 2023, MDF initiated a processto strengthen and further develop the Resilience Snapshot so

that it is more strongly tied to resilience theory and more generalisable across agro-ecological zones

and hierarchical levels.

MDF conceptualizes climate change adaptation for smallholder farmers through climate-resilient

agriculture or CRA on three nested levels: micro-, meso- and macro-levels (Error! Reference source

not found.). At the micro-level, participants are farmers interacting with each other - and possibly

14

others in their community - in peer learning groups, interest groups and committees. As one moves

to the meso- and macro-levels, the range and diversity of people and organisations involved broadens

out to include other players such as local and national government, civil society organizations (CSOs),

non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the private sector and academic institutions. The

connections across the three levels or scales are important for ensuring that farmers’ issues, concerns

and preferences are understood and taken up regionally and nationally (e.g. into policy, planning and

communications), and that farmers are able to benefit from the support of these diverse stakeholders

(e.g. through relationships, learning exchanges and training).

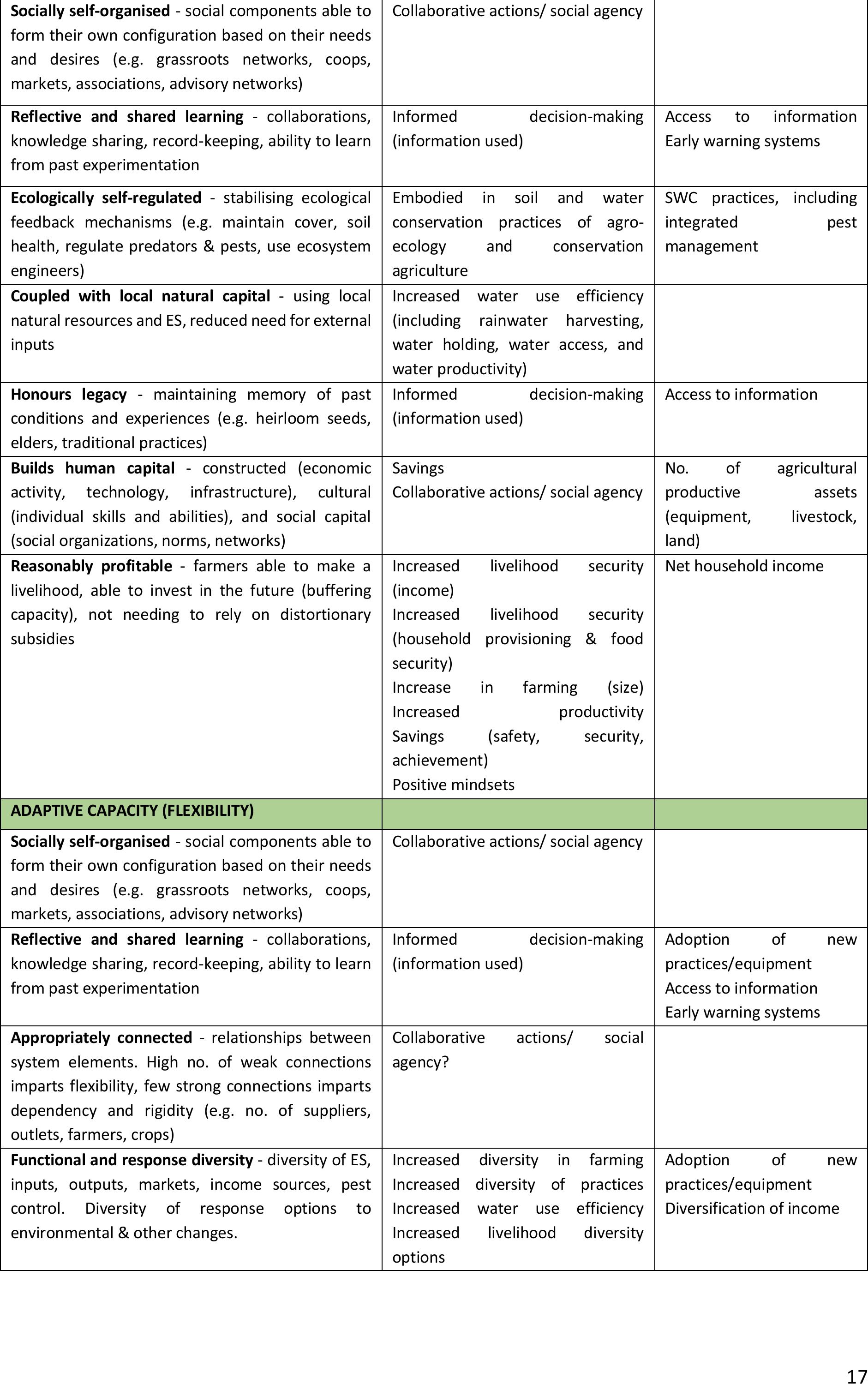

b.A theoretical foundation for assessing resilience of smallholder farming systems

The first step in strengthening MDF’s tools for assessing smallholder farmer resilience was to

strengthen the underlying theoretical framework. This was done by combining Cabell and Oelofse’s

indicators of agroecosystem resilience (Cabell and Oelofse, 2012) with the concept of absorptive,

adaptive and transformative resilience capacities as used by Oxfam and others (Jeans et al., 2017), to

produce the theoretical framework shown inthe figure below.

Cabell and Oelofse’s (2012) indicators of agro-ecosystem resilience have a solid foundation in that

they are based on the resilience principles outlined by Biggs et al. (2012), Biggs et al. (2015) and

numerous other resilience scholars (see Folke, 2006 foran overview). Cabell and Oelofse (2012)

present thirteen behaviour-based indicators1which together provide a measure of agro-ecosystem

resilience, particularly for smallholder farmers (see Table 4). Agroecosystems are defined as social-

1These are not specific, measurable indicators, but rather aspects or dimensions of resilience that should be

included.

Figure 2: Micro-, meso- and macro-levels of organisation for climate-resilient smallholder agriculture

15

ecological systems bounded by the intentionality to produce food, fuel or fibre and influenced by

farmers’ decision-making, including the physical space and resources usedas well as related

infrastructure, markets and institutions at multiple, nested scales (Cabell and Oelofse, 2012).

Cabell and Oelofse’s framework forms the basis for the SHARP+2tool (Hernandez et al., 2022;

https://www.fao.org/in-action/sharp), which is being widely used by the FAO and others to assess

household climate resilience based on the knowledge and priorities of farmers, using an integrated

approach. For example, the IFAD and GEF-financed Resilient Food Systems Impact Programme is

currently using SHARP+ in seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa as part of its monitoring and

evaluation framework, and SHARP+ has also been included in operational guidelines on monitoring

and evaluation of nature-based interventions, climate adaptation in agriculture, and implementation

of resilience thinking (Hernandez et al., 2022).

The Oxfam Framework for Resilient Development, The Future is a Choice, describes three types of

resilience capacity: absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacity (Jeans et al., 2016). Resilience is

seen as a result of enhancing the capacity(ability, agency, power)of peopleto proactively and

positively manage change in ways that contribute to a just world without poverty. The three capacities

are seen as interconnected, existing at multiple levels, and mutually reinforcing (Jeans et al., 2017).

This is in line with prominent resilience scholars’ characterisation of resilience as having dimensions

of persistence, adaptability and transformability in complex social-ecological systems (Walker et al.,

2004; Folke, 2006; Folke, 2016).

Absorptive capacity ensures stability because it aims to prevent or limit the negative impactof shocks.

It is the capacity to ‘bounce back’ after a shock, throughanticipating, planning, coping with and

recovering from specific shocks and short-term stresses. Adaptive capacity is the capacity to make

2Self-evaluation and Holistic Assessment of climate Resilience of farmers and Pastoralists.

Figure 3: Theoretical framework for assessing resilience ofsmallholder farmers. Based onCabell &

Oelofse (2012) and Jeans et al.(2017).

16

intentional incremental adjustments in anticipation of or in response to change, in ways that create

more flexibility in the future. Transformative capacity is the capacity to intentionally change the deep

structures that cause or increase vulnerability and risk as well as how risk is shared within societies

and the global community (Jeans et al., 2017).

For the purpose of creating a coherent theoretical framework for resilience in this context, the

different aspects of agroecosystem resilience described by Cabell and Oelofse (2012) were mapped

onto the three types of resilience capacity as shown in Figure 3, to produce a guiding framework for

monitoring and evaluating resilience.This framework includes the different aspects of resilience as

well as the interplay between stability and change.

c.Revision of the MDF resilience snapshot tool

The SHARP+ tool was considered too complicated for MDF’s current purpose, as it involves a very

lengthy survey which MDF felt would not be practical in the contexts in which it works. Although the

length and the questions can be customised to some extent, it was considered not ideal to combine

all the monitoring and evaluation into a single survey carried out at one point in time. As described

above, MDF staff already do several different types of monitoring and evaluation activities with

farmers on different time scales, because different activities require different monitoring frequencies.

Furthermore, MDF’s Resilience Snapshot tool has been tested and refined for the South African

context over many years. It was therefore decided to align what MDF is already doing with the Cabell

and Oelofse framework, and to strengthen and modify the Resilience Snapshot where necessary.

Comparing the Resilience Snapshot indicators with the Cabell and Oelofse (2012) aspects of

agroecosystem resilience (Table 1) revealed that the Resilience Snapshot did cover most areas,

although some more strongly than others. By comparison, the Committee on Sustainable

Assessment’s (COSA)3resilience indicators used by the Adaptation Fund do not cover all the aspects

of resilience (Table 4).

The thirteen aspects of agroecosystem resilience described by Cabell and Oelofse (2012) were reduced

to ten as follows. One was removed because it was felt not to be relevant to South African smallholder

farmers (“carefully exposed to disturbance” – South African smallholder farmers do not have the

luxury of controlling the amount of disturbance to which their activities are exposed). Another

(“coupled with local natural capital”) was removed because it was felt to be sufficiently covered by

another (“globally autonomous and locally interdependent”). Finally, “functional and response

diversity” and “optimally redundant” were combined because in practice having more diversity usually

also provides redundancy, or the ability of some entities (e.g. inputs, outputs or crops) to functionally

compensate for the loss of others (Kotschy, 2013).

Table 4: Alignment of the MDF Resilience Snapshot indicators and the COSA resilience indicators with the dimensions of

agroecosystem resilience described by Cabell and Oelofse (2012)

Cabell & Oelofse (2012)

Agroecosystem resilience

MDF Resilience Snapshot

COSA resilience indicators

used by Adaptation Fund

ABSORPTIVE CAPACITY (STABILITY)

3A non-profit independent global consortium which hasdevelopedanindicator library for resilience. COSA

indicators are aligned with global norms such as the SDGs, multilateral guidelines, international agreements,

and normative references. The indicators ensure comparability and benchmarking across regions or countries,

making it easierfor managers and policymakers.

17

Socially self-organised- social components able to

form their own configuration based on their needs

and desires (e.g. grassroots networks, coops,

markets, associations, advisory networks)

Collaborative actions/ social agency

Reflective and shared learning- collaborations,

knowledge sharing, record-keeping, ability to learn

from past experimentation

Informed decision-making

(information used)

Access to information

Early warning systems

Ecologically self-regulated - stabilising ecological

feedback mechanisms (e.g. maintain cover, soil

health, regulate predators & pests, use ecosystem

engineers)

Embodied in soil and water

conservation practices of agro-

ecology and conservation

agriculture

SWC practices, including

integrated pest

management

Coupled with local natural capital -using local

natural resources and ES, reduced need for external

inputs

Increased water use efficiency

(including rainwater harvesting,

water holding, water access,and

water productivity)

Honours legacy- maintaining memoryof past

conditions and experiences (e.g. heirloom seeds,

elders, traditional practices)

Informed decision-making

(information used)

Access to information

Builds human capital- constructed (economic

activity, technology, infrastructure),cultural

(individual skills and abilities), and social capital

(social organizations, norms, networks)

Savings

Collaborative actions/ social agency

No. of agricultural

productive assets

(equipment, livestock,

land)

Reasonably profitable - farmers able to make a

livelihood, able to invest inthefuture (buffering

capacity), not needing to rely on distortionary

subsidies

Increased livelihood security

(income)

Increased livelihood security

(household provisioning & food

security)

Increase in farming (size)

Increased productivity

Savings (safety, security,

achievement)

Positive mindsets

Net household income

ADAPTIVE CAPACITY (FLEXIBILITY)

Socially self-organised- social components able to

form their own configuration based on their needs

and desires (e.g. grassroots networks, coops,

markets, associations, advisory networks)

Collaborative actions/ social agency

Reflective and shared learning- collaborations,

knowledge sharing, record-keeping, ability to learn

from past experimentation

Informed decision-making

(information used)

Adoption of new

practices/equipment

Access to information

Early warning systems

Appropriately connected- relationships between

system elements. High no. of weak connections

imparts flexibility, few strong connections imparts

dependency and rigidity (e.g. no. of suppliers,

outlets, farmers, crops)

Collaborative actions/ social

agency?

Functional and response diversity- diversity of ES,

inputs, outputs, markets, income sources, pest

control. Diversity of response options to

environmental & other changes.

Increased diversity in farming

Increased diversity of practices

Increased water use efficiency

Increased livelihood diversity

options

Adoption of new

practices/equipment

Diversification of income

18

Optimally redundant- duplication (partial

functional overlap) of components and

relationships in the system (e.g. crop types,

equipment, watersources, nutrient sources, sales

outlets), but not so that it is too costly/unwieldy

Increased diversity in farming

Increased diversity of practices

Increased water use efficiency

Increased livelihood diversity

options

No. of income sources

Spatial and temporal heterogeneity - patchiness of

land use, rotations, practices, in space and over

time

Increased growing season

Increased diversity in farming

(gardening/ fieldcropping/

livestock/ trees)

Carefully exposed to disturbance - disturbance not

excluded totally but managed where possible (e.g.

pest and disease exposure allowed to promote

selection and resistance)

TRANSFORMATIVE CAPACITY (STRUCTURAL

CHANGE)

Reflective and shared learning- collaborations,

knowledge sharing, record-keeping, ability to learn

from past experimentation

Collaborative actions/ social agency

Adoption of new

practices/equipment

Access to information

Early warning systems

Socially self-organised- social components able to

form their own configuration based on their needs

and desires (e.g. grassroots networks, coops,

markets, associations, advisory networks)

Informed decision-making

(information used)

Globally autonomous and locally inter-dependent

- relative autonomy from exogenous control, but

with a high level of cooperation locally

Collaborative actions/ social agency

Specific, measurable indicators were then developed for all the aspects of resilience and resilience

capacity as shown in Figure 3, using the existing indicators in MDF’s Resilience Snapshot and the COSA

indicators as a starting point. Further development is still required, for example to add the

methodology, people responsible for data collection and analysis, frequency of collection and data

limitations for each indicator.

Ongoingwork will involve developing a visually engaging way of presenting and sharing the data. This

could include:

•A “traffic light” system (red, orange, green) for each indicator to provide a simple overview of

status and progress.

•Web-based dashboards which convert the data into engaging visual representations (e.g.

graphs, charts, tables, word clouds) and make it accessible to stakeholders.

•An interactive network mapping tool such as Kumu (https://kumu.io/), which allows

stakeholders to map and visualise their connections interactively and can also be used to

gather and analyse data such as numbers andtypes of connections, strength of connections

and social self-organisation.

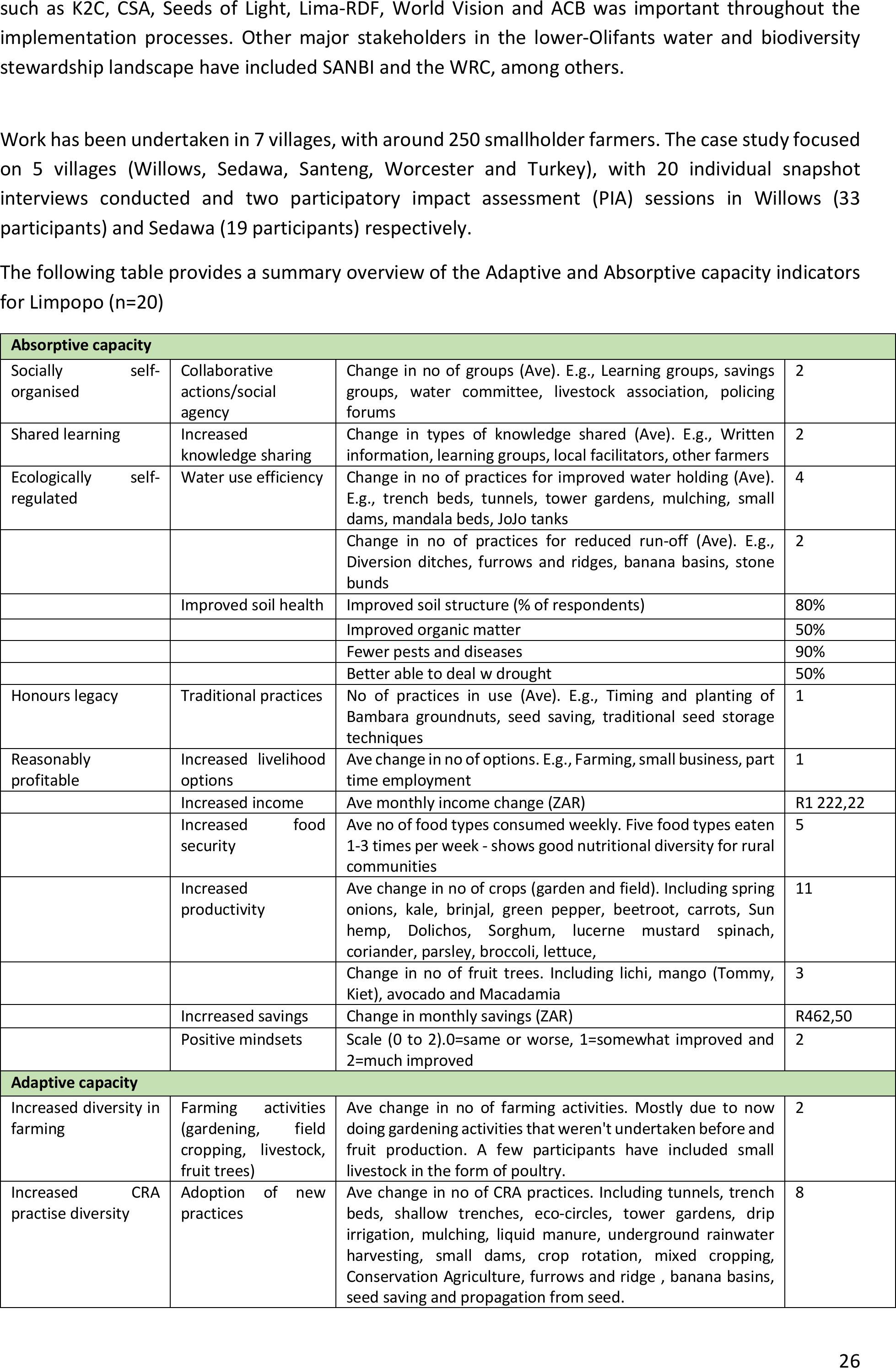

Table 5: Expanded and modified set of resilience indicators for MDF’s Resilience Snapshot

Indicator name and no.

Rationale

Definition

Unit of measure

Absorptive capacity

19

1. Socially self-organised (Focus on support networks)

1.1 Support

networks/groups

Support networks build absorptive

capacity by helping farmers to

absorb and survive shocks.

Networks or groups which

farmers use for emergency and

psycho-social support.

Average no. of groups, %

of farmers belonging to

different types of groups.

1.2 Increased social

agency (collaborative

actions)

Absorptive capacity is enhancedby

support networks that enable

individual and collective agency to

make farming activities more

efficient and productive.

Extent of collaboration e.g.

Market days, assistance with

ploughing, labour, seed sharing,

saving groups etc.

Average no. of

collaborative actions in

which farmers are

involved.

2. Shared learning (Focus on learning for productivity)

2.1 Increased knowledge

sharing

Sharing of knowledge helps farmers

to farm more effectively and to

mitigate the impacts of shocks and

disturbances. Also, the act of

sharing knowledge promotes

learning for the person doing the

sharing as well as the recipient.

Sharing shows that people have

internalised information.

How knowledge isshared (e.g.

informally with other farmers,

in meetingswith local orgs,

meetings withexternal orgs

such as DoA interest groups, in

coops).

What is shared: categories/

types of knowledge or sharing.

List of who shared with,

list of types of knowledge

shared.

3. Ecogically self-regulated

3.1 Increased water use

efficiency

Five fingers indicators

Pest and disease

management

Pollinators

The 5 fingers principles promote

ecological self-regulation through

improved nutrient cycling, water

use efficiency, soil health,

maintenance ofindigenous

vegetation and pollinator

populations. Important for

resilience but MDF has not had any

success withmonitoring most of

these. Most farmers are not aware

of things like pollinators, pests and

diseases, soil health.

Whether the soil's water-

holding capacity has improved

(Y/N).

% Y vs N responses

4. Honours legacy

4.1 Traditional practices,

crops and livestock in use

Traditional practices are a way of

maintaining memory ofpast

conditions and experiences.

Whichtraditionalpractices are

in use? (e.g. seed saving,

heirloom/indigenous seeds or

breeds, banana basins) - or

changes to these.

List of traditional

practices being used by

farmers

5. Builds human capital

5.1 Increased savings

Savings provide a buffer, allowing

farmers to absorb and recover from

shocks, and to plan and manage

their cash flow.

Average increase in savings

Average increase in

savings (Rands)

5.2 Use of savings for

livelihoods improvement

If farmers are using savings for

livelihood improvements, rather

than just on essentials such as food,

it suggests that human capital is

being built.

How savings are being used

List of options

5.3 Increased knowledge

and agency as a result of

CRA

Building skills, knowledge and

agency increases human capital,

which enables farmers to farm more

effectively.

What farmers areable todo

now that they weren't able to

do before

List of options

20

5.4 Increase in agricultural

productive assets

Agricultural assets enable farmers

to farm effectively and to absorb

and recover from shocks.

Change in agricultural

productive assets

List, maybe count and

categorise (equipment,

livestock, etc.)

6. Reasonably profitable

6.1 Increased income

If farmers are able to make a

livelihood through farming, they are

able to remain in their communities

and provide for their families,

avoiding the social and

psychological disruption of

migration or circular migration.

Average monthly incomes,

mostlythough marketing of

produce locally and through the

organic marketing system.

Average monthly income

(Rands)

6.2 Increased household

food provisioning

If farmers are able to produce

sufficient food locally, it reduces

their dependency on store-bought

food.

Food produced and consumed

in the household.

Overall food produced (kg

per week)

6.3 Increased food

security

Having a dependable supply of food

and a good variety of foods is

beneficial for health and wellbeing.

No. of food types and how often

eaten. A recognised food

security indicator.

No. offood types/ no. of

times per week

6.4 Increase in size of

farming activities

An expansion of farming indicates

that farmers have the resources and

commitment to make this possible.

Size of farming activities

(cropping, trees & livestock).

Cropping area (ha), no. of

fruit trees and no of

livestock.

6.5 Increased productivity

Apart from food security, increases

in productivity create opportunities

for participation in markets or

value-added activities.

Increase in yields and/or

livestock.

Overall kg produced in a

season, livestock

increase/decrease

6.6 Increased savings

An increase in savings reflects

successful livelihoods. Savings also

allow farmers to invest in the

future.

Average increase in savings.

Average increase in

savings (Rands).

6.7 Positive mindsets

This is an integrative measure of

whether farmers feel they are

"making it".

How positive farmers feel about

the future.

SCALE: 0=less positive

about the future; 1=the

same; 2=more positive;

3=much more positive.

Adaptive capacity

1. Socially self-organised (Focus on learning networks)

1.4 Learning

networks/groups

Learning networks build adaptive

capacity by promoting

experimentation and evaluation of

results.

Networks or groups to which

farmers belong which enable

learning about CRA. (Will be

mainlyjust the MDF learning

group in most cases).

Average no. of groups, %

of farmers belonging to

different types of groups.

2. Shared learning (Focus on learning for adaptation)

2.2 Use of information

from past

experimentation in

decision-making

Successful adaptation is more likely

when experimentation and learning

inform farmers' decisions.

Whether information from past

experimentation is used

% of farmers using info

from past

experimentation

2.3 Prevalence of record-

keeping

Record-keeping facilitates recallof

past events/results and analysis of

trends.

Whether farmers keep records

of anything

Question Y/N

2.4 Most significant

change in farming

practices

Changed practices indicate learning

(?)

Most significant change in

farming practices

List of practices

21

7. Diversity and redundancy

7.1 Increased livelihood

diversity options

Having a diversity oflivelihood

options increases farmers' response

diversity (capacity to adapt to

different shocks).

No. of livelihood options

(sources of income), e.g. Social

grants, remittances, farming

incomes,small business

income, employment.

Average no. of options per

farmer

7.2 Increased diversity of

farming activities

Having a diversity of farming

activities also increases response

diversity and provides for spreading

of risks.

No. of farming activities

(gardens, field cropping,

livestock, trees etc.).

Average no. of activities

per farmer

7.3 Increased crop

diversity

Increased crop diversity increases

functional and response diversity

(different crops perform different

roles, provide different nutritional

benefits, and respond differently to

stress, disease and disturbance).

No. of crops planted by farmers

which werenot planted

previously ("new" crops).

Average no. of"new"

crops added, overall and

per farmer

7.4 Increased CRA

practice diversity

Different practices have different

functions within the agro-

ecosystem (functional diversity).

No. of CRA practices usedby

farmers which were not used

previously (e.g. mulching,

trench beds, liquid manure,

raised beds, mixed cropping,

inter-cropping, crop rotation,

tunnels, drip kits, eco-circles, ,

greywater use and

management, Conservation

Agirculture, cover crops,

inclusion of legumes, pruning of

fruit trees, picking up dropped

fruit, pest and disease control

,feeding livestock on crops and

stover, cutting and baling,

fodder supplementation, health

and sanitation for poultry,

brooding, JoJo tanks, RWH

drums).

Average no. of"new"

practices added, overall

and per farmer

7.5 No. of water sources

Redundancy in water supply

reduces the impact of failure of one

source.

List of water sources available

to farmer.

Average no. of water

sources, overall and per

farmer

7.6 No. ofnutrient

sources

Redundancy in nutrient supply.

List of nutrient sources available

to farmer.

Average no.of nutrient

sources, overall and per

farmer

7.7 No. of suppliers

Redundancy in of supply of inputs.

No. of suppliers available to

farmers for gardening, field

cropping and livestock needs.

Average no. of suppliers

available, overall and per

farmer

7.8 No. of sales outlets

Redundancy in sales outlets.

No. of sales outlets available to

farmers for selling produce from

gardening, field cropping and

livestock.

Average no.ofsales

outlets available, overall

and per farmer

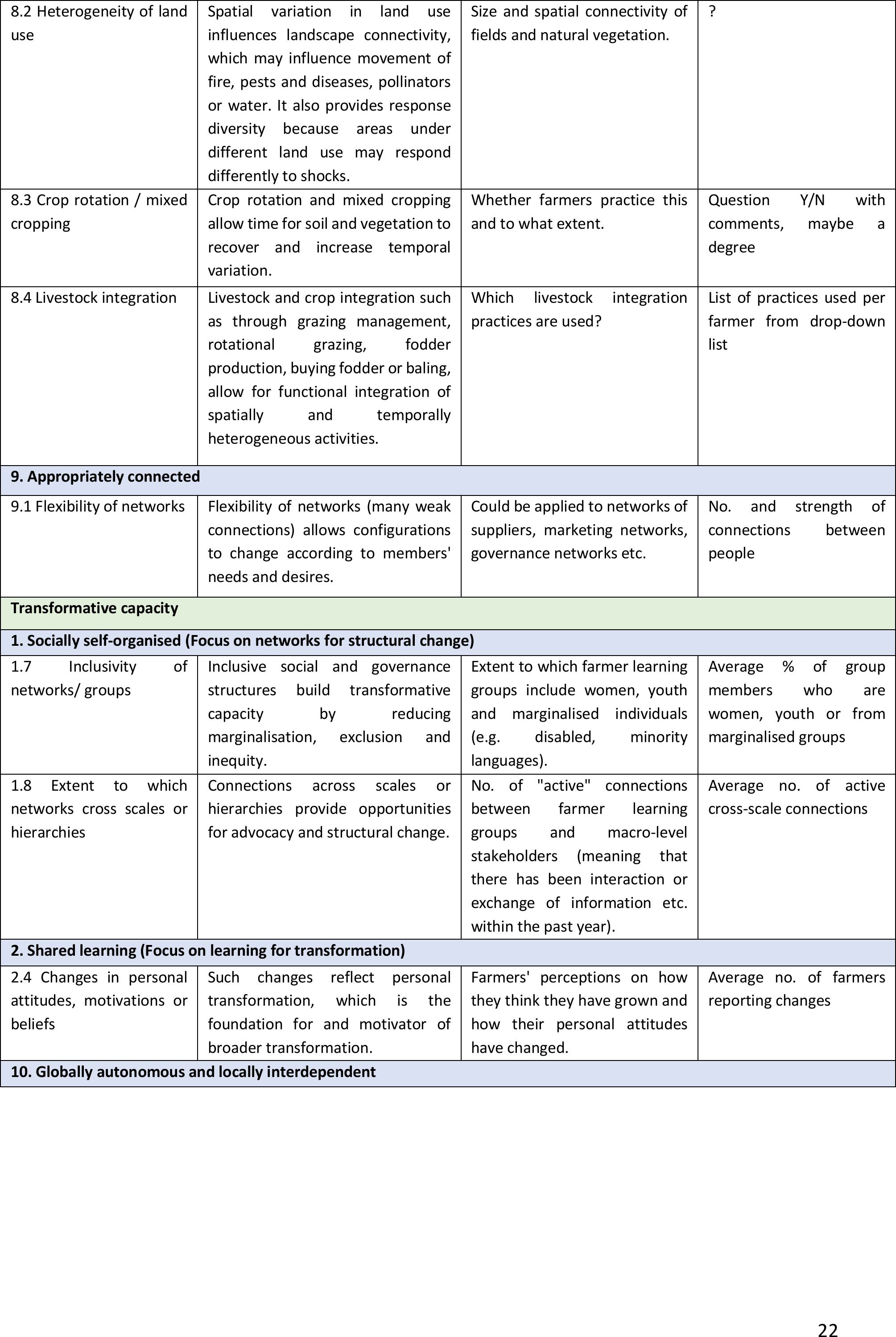

8. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity

8.1 Increased season

Seasonal variation of activities

determines how farming benefits

are distributed in time.

Has the seasonal extent of

farming increased? (i.e. autumn

and winter, and all-year

options).

Question Y/N

22

8.2 Heterogeneity of land

use

Spatial variation in land use

influenceslandscape connectivity,

which may influence movementof

fire, pests and diseases, pollinators

or water. It also provides response

diversity because areas under

different land use may respond

differently to shocks.

Size and spatial connectivity of

fields and natural vegetation.

?

8.3 Crop rotation / mixed

cropping

Crop rotation and mixed cropping

allow time for soil and vegetation to

recover and increase temporal

variation.

Whether farmers practice this

and to what extent.

Question Y/N with

comments, maybe a

degree

8.4 Livestock integration

Livestock and crop integration such

as through grazing management,

rotational grazing, fodder

production, buying fodder or baling,

allow for functional integration of

spatially and temporally

heterogeneous activities.

Whichlivestock integration

practices are used?

List of practices used per

farmer from drop-down

list

9. Appropriately connected

9.1 Flexibility of networks

Flexibility of networks (many weak

connections) allows configurations

to change according to members'

needs and desires.

Could be applied to networks of

suppliers, marketing networks,

governance networks etc.

No. and strength of

connections between

people

Transformative capacity

1. Socially self-organised (Focus on networks for structural change)

1.7 Inclusivity of

networks/ groups

Inclusive social and governance

structures build transformative

capacity by reducing

marginalisation, exclusion and

inequity.

Extent to which farmer learning

groups include women, youth

and marginalised individuals

(e.g. disabled, minority

languages).

Average % of group

members who are

women, youth or from

marginalised groups

1.8 Extent to which

networks cross scales or

hierarchies

Connections across scales or

hierarchies provide opportunities

for advocacy and structural change.

No. of "active" connections

between farmer learning

groups and macro-level

stakeholders (meaning that

there has been interaction or

exchange of information etc.

within the past year).

Average no. of active

cross-scale connections

2. Shared learning (Focus on learning for transformation)

2.4 Changes in personal

attitudes, motivations or

beliefs

Such changes reflect personal

transformation, which is the

foundation for and motivator of

broader transformation.

Farmers' perceptions on how

they think they have grown and

how their personalattitudes

have changed.

Average no. of farmers

reporting changes

10. Globally autonomous and locally interdependent

23

10.1 External vs local

inputs

If farmers are highly dependent on

external inputs,they will be at the

mercy of external structures and

circumstances (e.g. wars, politics,

inflation, multi-national

corporations) and will therefore

have little ability to bring about

structural change. Ifinputs are

obtained locally, it suggests local

interdependence.

No. of external inputs divided by

no. of local inputs (e.g. seed,

fertiliser, pest control products,

feed etc.)

Ratio ofexternal to

internal inputs

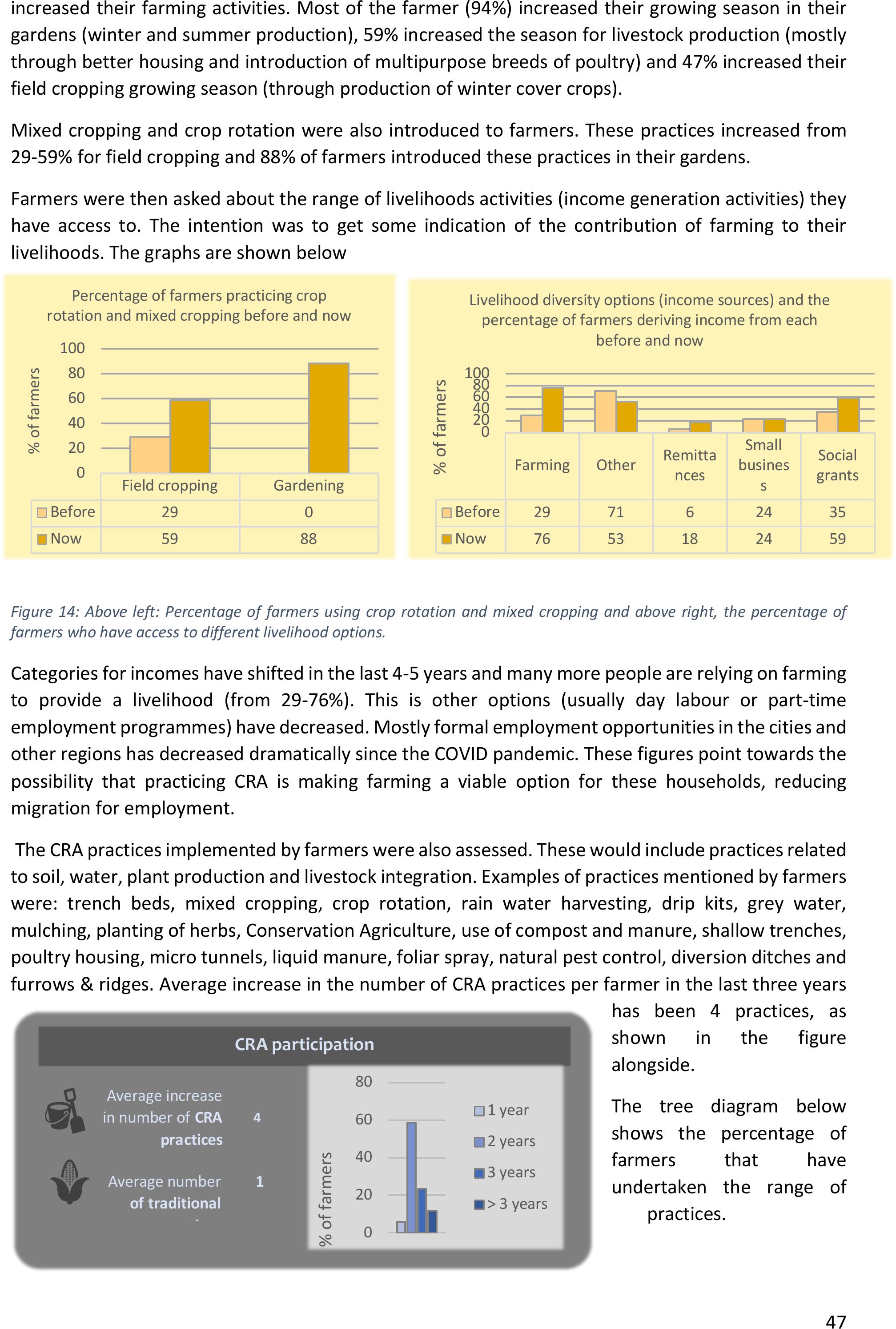

An important considerationin developing the indicators in Table 5 5 was how to promote coherent

monitoring and evaluation across the different scales (micro-, meso- and macro-levels as shown in

Figure 2). The two aspects of resilience shown in the intersections between the three circles inFigure

3, namely social self-organisation and shared learning, are important for all three types of resilience

capacity and at all three levels, although they are expressed in slightly different ways in each. For

example, at the micro-level, farmer self-organisation is measured by the number of local groups that

provide support, the inclusivity of groups, and the extent of collaborative actions among farmers. At

the macro-level, similar indicators for social self-organisation are used, but they are applied at the

regional or national level (e.g. collaborative actions would not be between individual farmers but

between organisations or groups). Additional indicators may also be included at higher levels, such as

whether all stakeholder groups are adequately represented.

3.3MERLTOOLS DEVELOPED

The resilience snapshot was improved and updated to incorporate the methodological considerations

in the section above. A copy of the survey form is provided in Attachment 1. These questionnaires are

called snapshots as they can be administered at any time in the individual’s progression towards

resilience. They are not project specific and are not meant as outcome assessments for projects, but

rather to highlight changes theparticipant has made to adapt to climate change and the assessment

of the improvedresilience from such changes. It is foreseen that it can be useful to undertake these

snapshots repeatedly over time to get an indication of ongoing improvement for the participant.

In addition to the individual interviews, there are aspects of resilience, notably social organisation,

changes in human capacity and learning related to climate change that is better analysed in groups as

these aspects are more relational in nature and rely on people’s understanding, thinking and opinions.

For these aspects a participatory impact assessment process was developed. The outline of these

discussions is provided in Attachment 2.

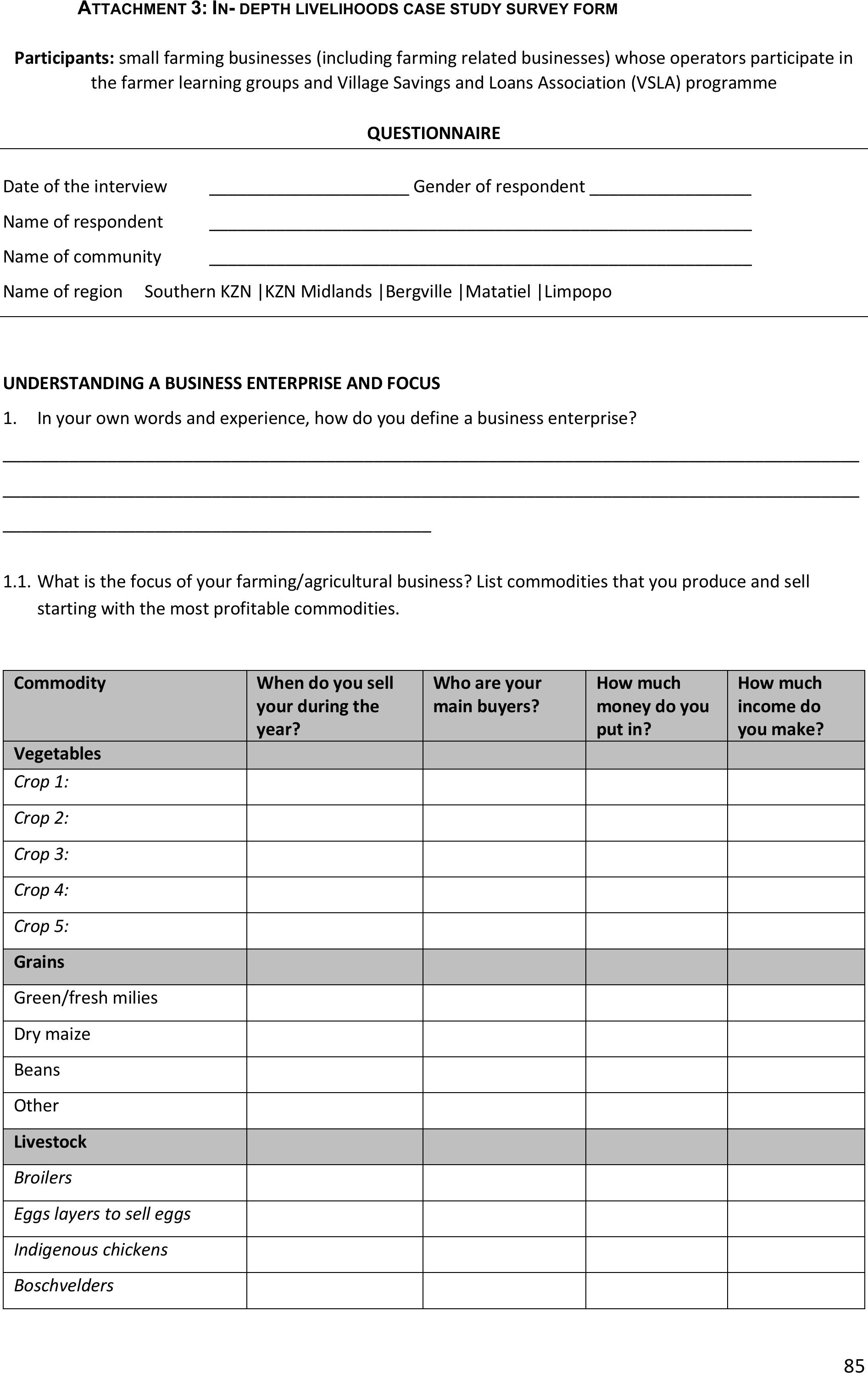

A third tool has been developed to explore in some depth the impact of the village savings and loan

associations (VSLAs) on a selected number of individuals’ income generation and business

development and expansion activities. The outline of this questionnaire is provided in Attachment 3.

Results from these three tools have been collated, analysed and summarisedinto the case studies

presented below.

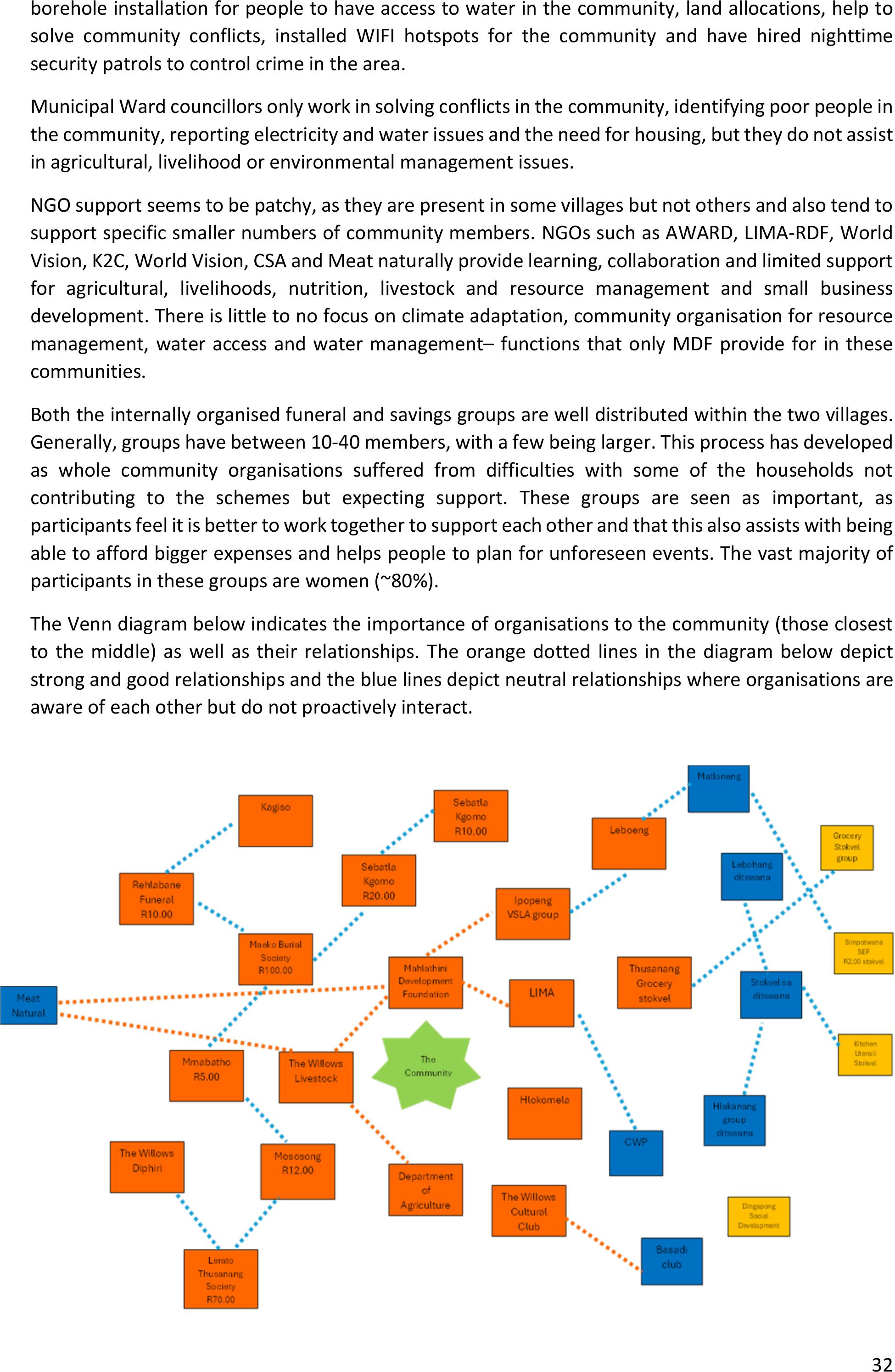

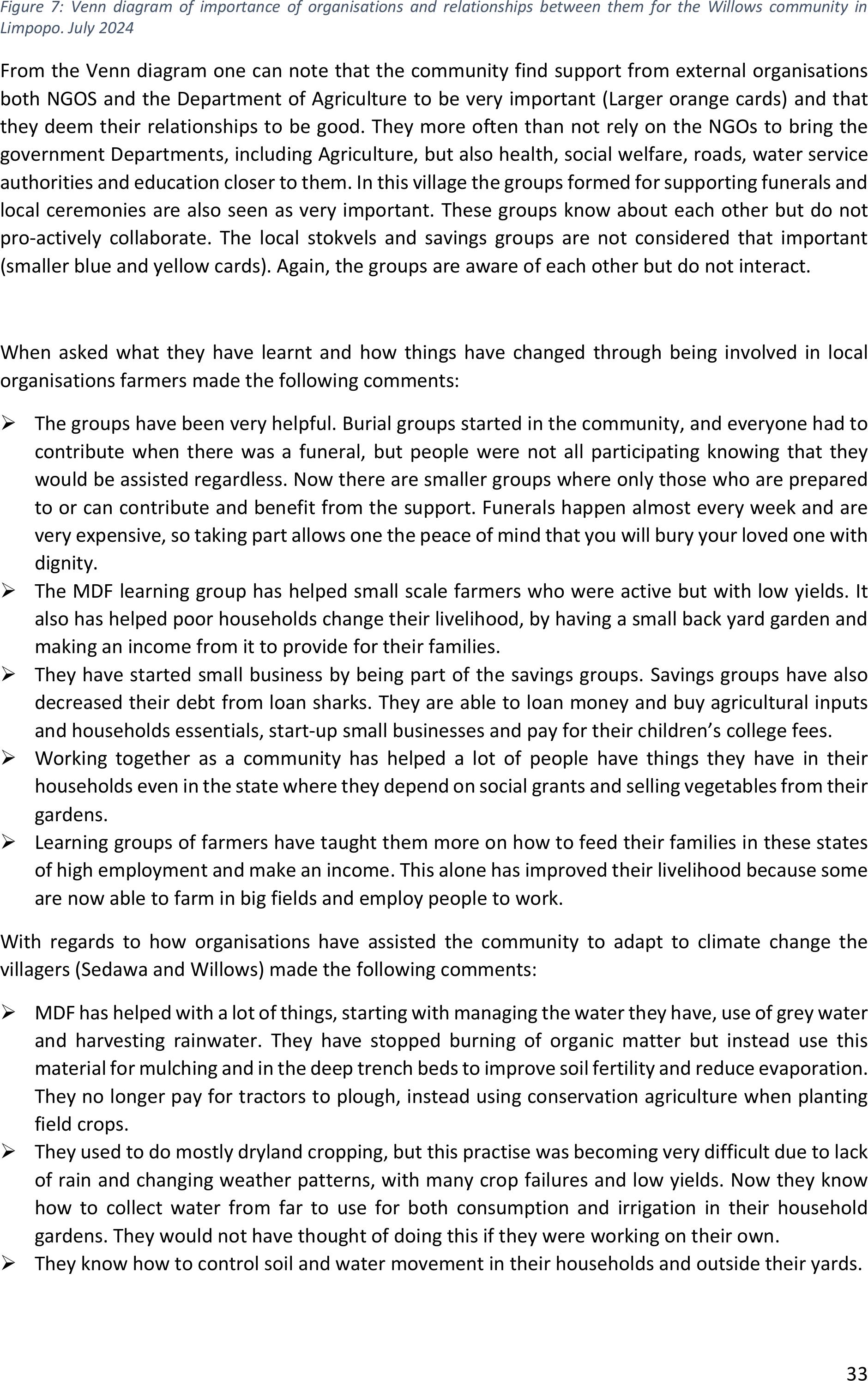

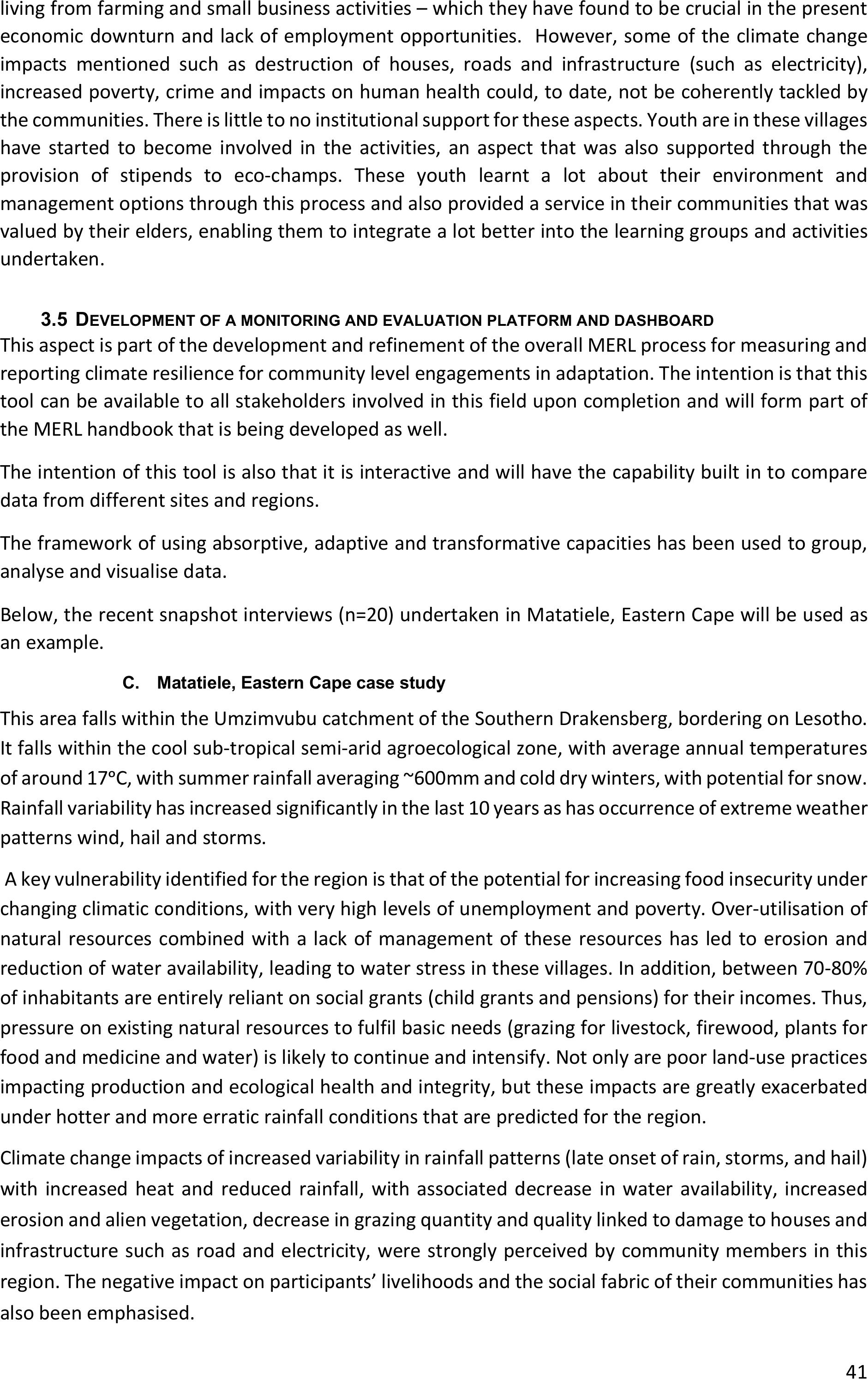

3.4AGROECOLOGICAL ZONE CLIMATE RESILIENCE CASE STUDIES

The community-based climate change adaptation approach and methodology used in all three

provinces has relied on village level learning groups and clusters of learning groups undertaking

24

cyclical analysis, implementation and review processes to explore adaptive strategies and processes

for adaptation to climate change, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 4: An outline of the learning group approach and processes for adaptions to climate change.

Incorporation of aspects from different themes within the smallholder farming system andthe natural

landscape has been undertaken through a ‘Five fingers” model to allow for implementation across a

wide range of activitiesincluding climate resilient agriculture, water and natural resources

management and stewardship and local governance.

Figure 5: the Five Finger model for implementation of

adaptive strategies to allow for a coherent systemic

approach and development of synergies across activities.

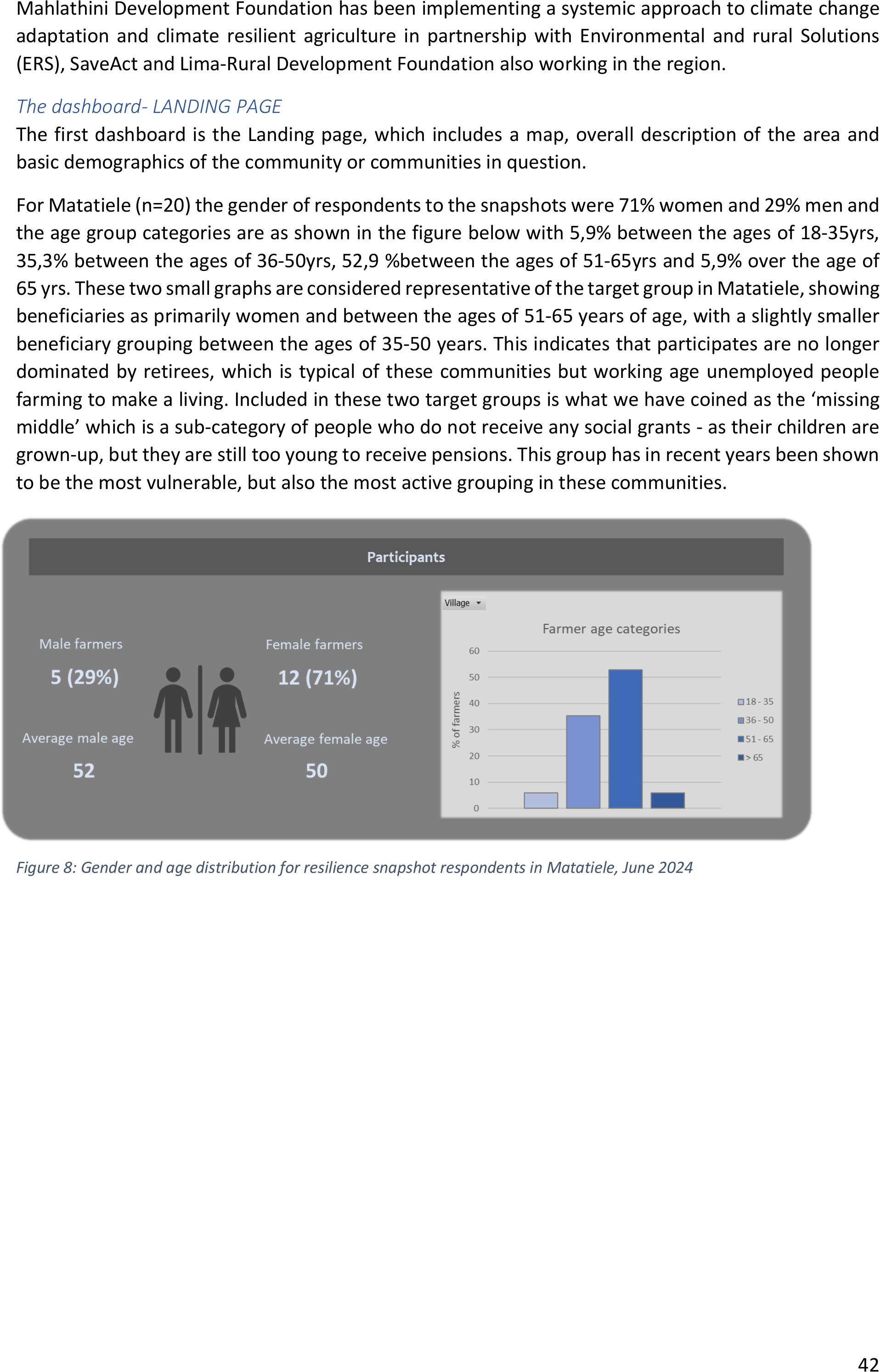

Climate Resilient Agriculture and innovation

system development for sustainable and

productive use of land and waterhas broadly

included the following activities:

Conservation/ Regenerative Agriculture: (LEI)

Quantitative research support to the

Smallholder Farmer Innovation Programme;

intercropping, crop rotation, cover crops,

fodder production

Livestock integration: Winter fodder

supplementation, hay baling, conservation

agreements, local livestock auctions

Intensive homestead food production:

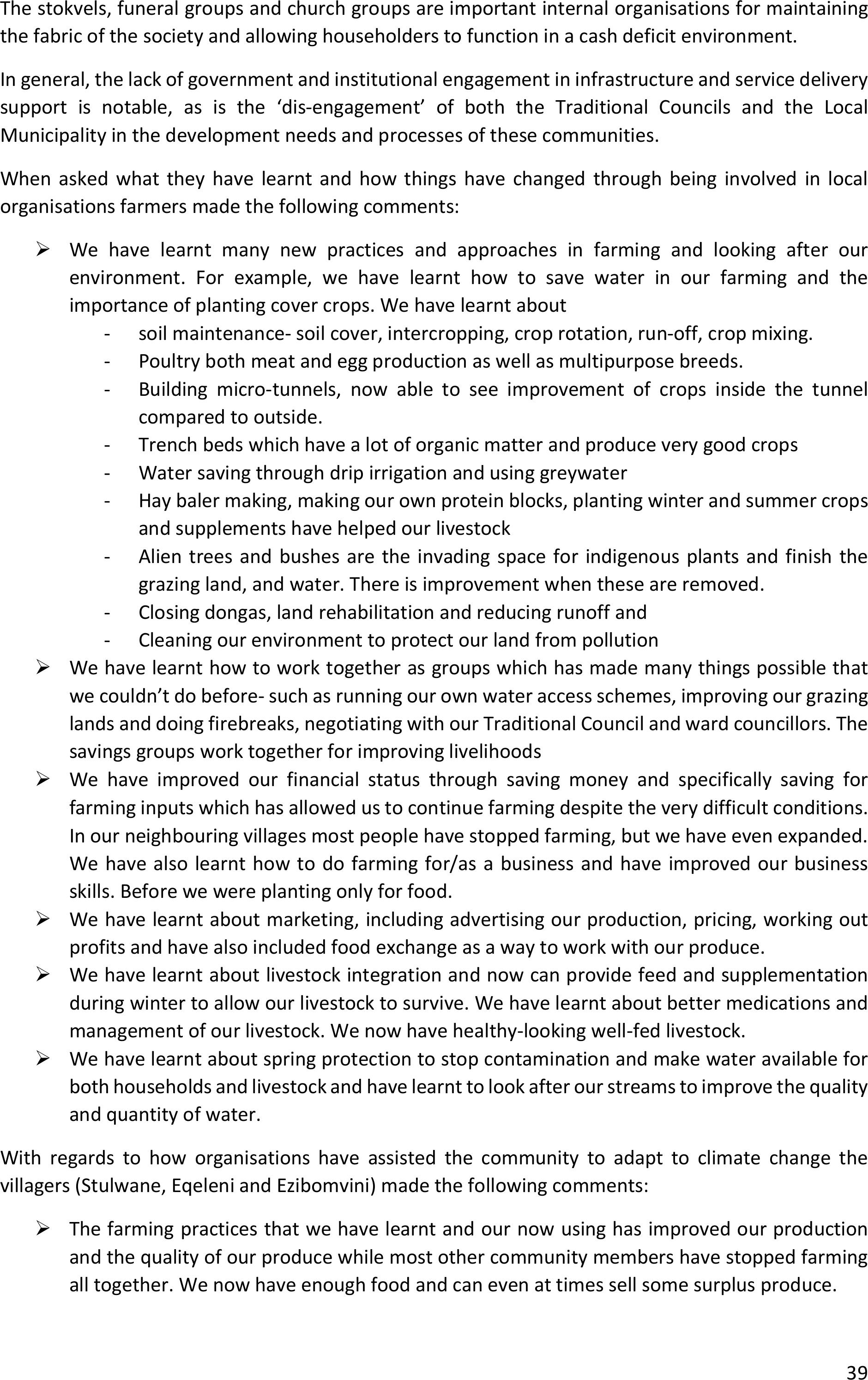

Agroecology; tunnels, trench beds, crop diversification, mulching, greywater management, fruit

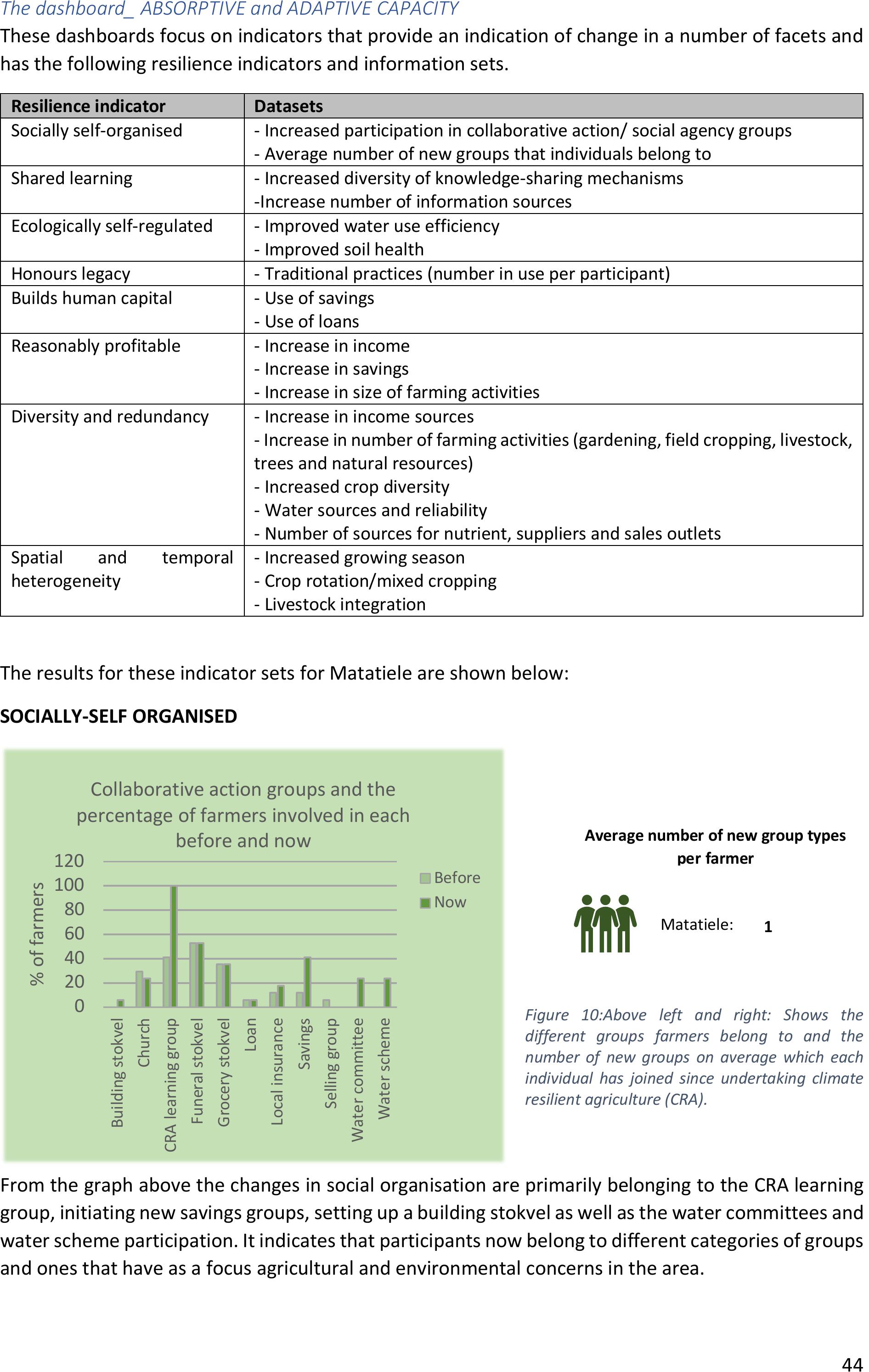

production