1

WaterResearchCommission

Submitted to:

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Project team:

Mahlathini Development Foundaction(MDF)

Erna Kruger

Temakholo Mathebula

Betty Maimela

Ayanda Madlala

Nqe Dlamini

Institute of Natural Resources (INR)

Brigid Letty

Environmental and Rural Solutions (ERS)

Nickie McCleod, Sissie Mathela

Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD)

Derick du Toit

Project Number: C2022/2023-00746

Project Title: Dissemination and scaling of a decision support framework for CCA for smallholder

farmers in South Africa

Deliverable No.2:Monitoring framework: Exploration of appropriate monitoring tools to suite the

contextual needs for evidence-based planning and implementation.

Date: 2 December2022

Deliverable

2

2

CONTENTS

ACRONYMS......................................................................................................................................3

1.Introduction............................................................................................................................5

2.Climate resilience monitoring tools and indicators................................................................. 8

1.1Global Commission on Adaptation..................................................................................9

a.Principles for climate resilience metrics..........................................................................9

2.1The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for South Africa.............................10

b.SANBI: Adaptation Fund................................................................................................13

c.Committee on Sustainable Assessment (COSA) resilience indicators...........................15

d.Locally Led Adaptation (LLA).........................................................................................18

3.Multi stakeholder engagement: Towards a coherent methodology.....................................20

a.SANBI Living catchments Project...................................................................................20

b.The uThukela Water Source Forum...............................................................................21

c.The uMzimvubu Catchment Partnership evaluation.....................................................24

3.1Monitoring and evaluation in multi stakeholder engagements....................................29

d.MEL and PMERL.............................................................................................................30

a.Examples.......................................................................................................................31

4.Process planning and progress to date.................................................................................32

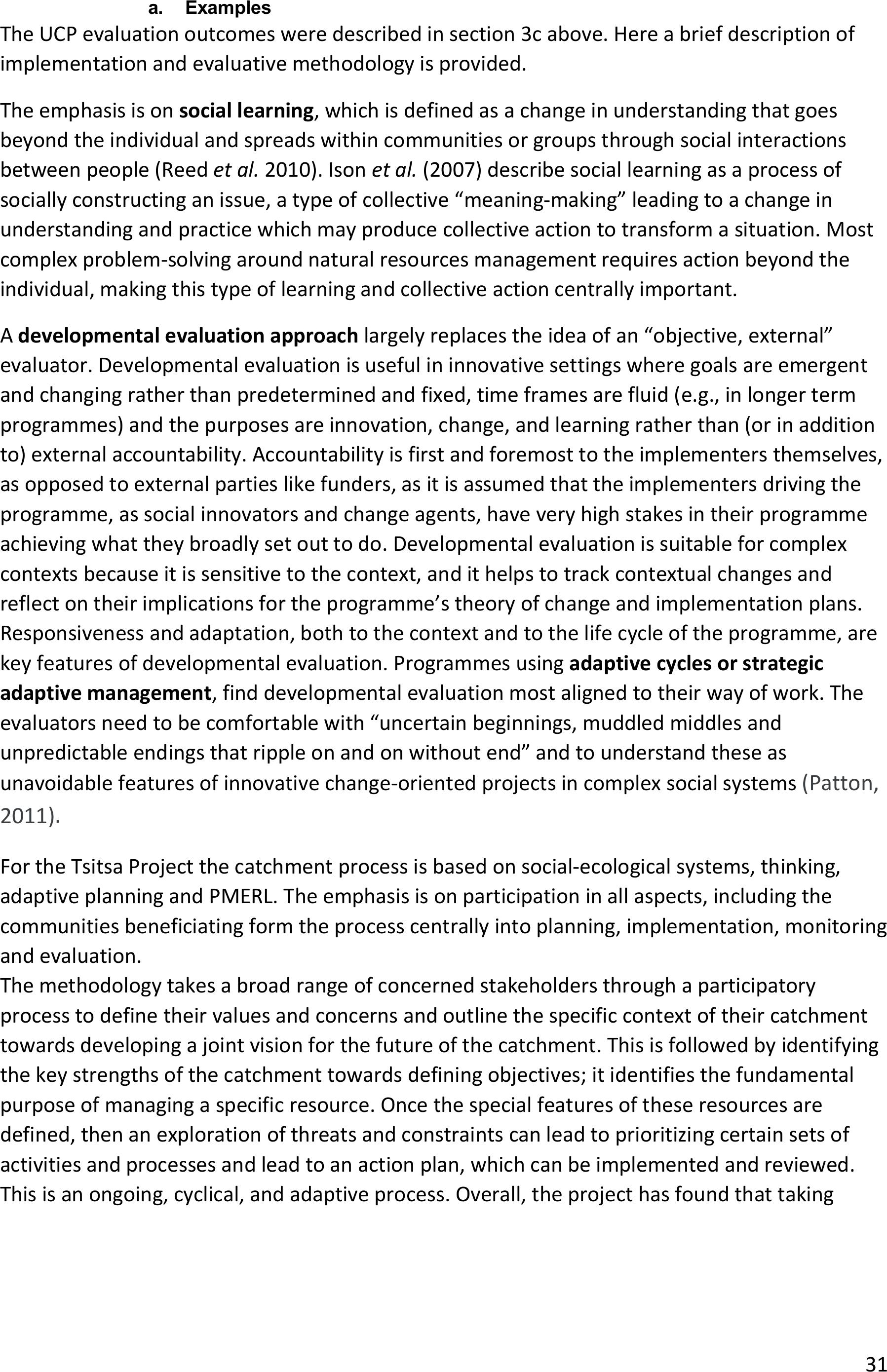

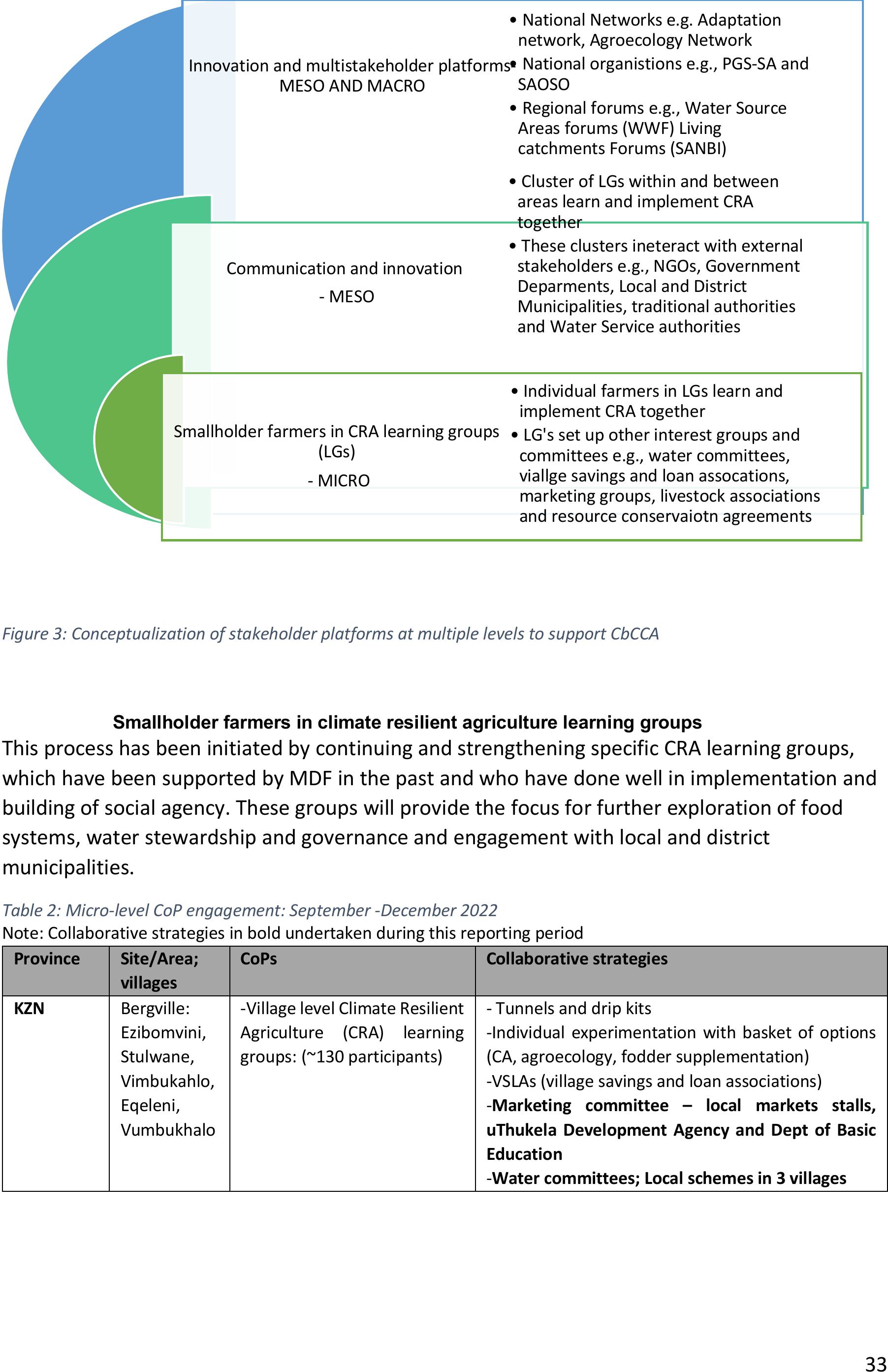

Smallholder farmers in climate resilient agriculture learning groups...................................33

Communication and innovation............................................................................................34

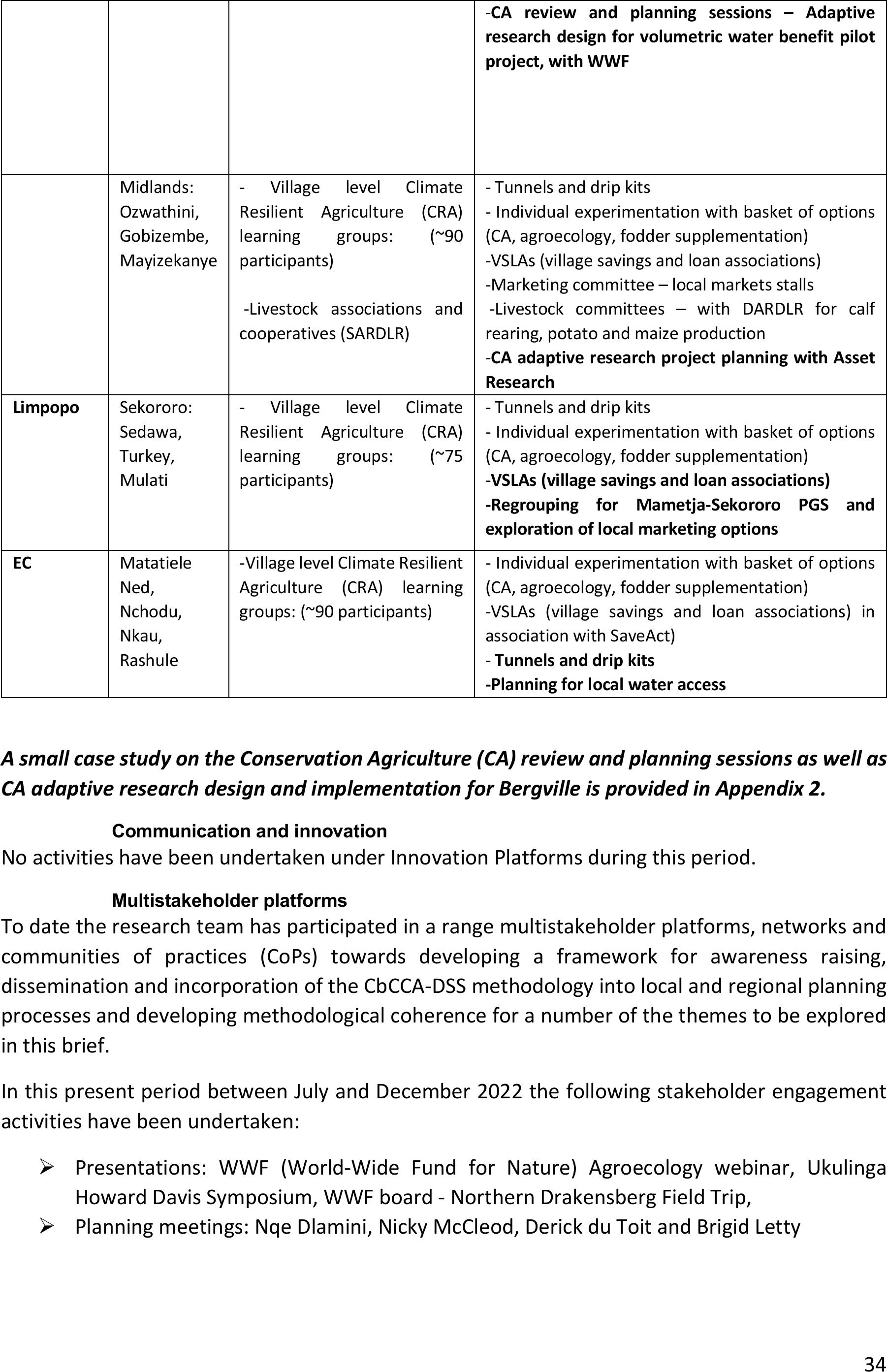

Multistakeholder platforms..................................................................................................34

4.1Work plan: December 2022 – February 2023...............................................................38

5.Reference s............................................................................................................................40

Appendix 1: Ukulinga Howard Davis Memorial Symposium presentation 2022/10/11................46

Appendix 2: CA learning group reviews nad planning: Bergville, August 2022.............................57

Collaboratively managed trials (CMTs) planning...................................................................59

Appendix 3: Adaptation Newsletter October 2022. Article..........................................................60

3

Figure 1: Frames to understand adaptation effectiveness range across a continuum of being

process- or outcome-based. Source: (Singh, et al., 2021).................Error! Bookmark not defined.

Figure 2: Critical processes to foster co-productive agility ineach of the four pathways to

sustainability transformations..........................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

Figure 3: The component of climate vulnerability and climate risk, adapted from IPCC AR5 ( (GIZ,

with EURAC and Adelphi, 2017)........................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

Figure 4: Conceptualization of stakeholder platforms at multiple levels to support CbCCA........33

ACRONYMS

AFAdaptation Fund

APPAdaptive planning process

CCAClimate change adaptation

COSACommittee on sustainable assessment

COP/CoPCommunity of Practice

CRAClimate resilient agriculture

CSOCivil society organisation

CbCCACommunity based climate change adaptation

DAOdesired adaptation outcome

DFFEDepartment of forestry, fisheries, and the environment

DMDistrict municipality

GCAGlobal commission on adaptation

IPInnovation platform

LGLearning group

LMLocal municipality

M&EMonitoring and evaluation

4

MDBMultilateral development bank

MELMonitoring, evaluation and learning

PMERLParticipatory monitoring, evaluation, reflection and learning

MSPMultistakeholder platform

NCCISNational climate change information system

NCCASNational climate change adaptation strategy

NDCNational determined contribution

NGONon-governmentorganisation

OECDOrganisation for economic cooperation and development

SANBISouth African National Botanical Institute

SDGSustainable development goal

SWSAStrategic water source area

UNFCCUnited Nations framework convention on climate change

5

1.INTRODUCTION

This section provides a brief summaryof the project vision, outcomes and operational details.

OUTCOME

Vertical and horizontal integration of this community- based climate change adaptation (CbCCA)

model and process lead to improved water and environmental resources management,

improved rural livelihoods and improved climate resilience for smallholder farmers in communal

tenure areas of South Africa.

EXPECTED IMPACTS

1.Scaling out and scaling up of the CRA frameworks and implementation strategies lead to

greater resilience and food security for smallholder farmers in their locality.

2.Incorporation of the smallholder decision support framework and CRA implementation into

a range of programmatic and institutional processes

3.Improved awareness and implementation of appropriate agricultural and water

management practices and CbCCA in a range of bioclimatic and institutional settings

4.Contribution of a robust CC resilience impact measurement tool for local, regional and

national monitoring processes.

5.Concrete examples and models for ownership and management of local group-based water

access and infrastructure.

AIMS

No

Aim

1.

Create and strengthen integrated institutional frameworks and mechanisms for

scaling up proven multi-benefit approaches that promote collective action and

coherent policies.

2.

Scaling up integrated approaches and practices in CbCCA.

3.

Monitoring and assessment of environmental benefits and agro-ecosystem

resilience.

4.

Improvement of water resource management and governance, including

community ownership and bottom-up approaches.

5.Chronology of activities

1.Desktop review of CbCCA policy and implementation presently undertaken in South

Africa

2.Set up CoPs:

a.Village based learning groups: A minimum of 1-3 LGs per province will be

brought on board.

6

b.Innovation platforms: 3 LG clusters, one for each province consisting of a

minimum of 9- 36 LGs will be identified to engage coherently in this research

and dissemination process.

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Engage existing multistakeholder platforms such as

the uMzimvubu catchment partnership, SANBI- Living Catchments Programme,

the Adaptation Network, etc.

3.Develop roles and implementation parameters for each CoP

a.Village based learning groups: CCA learning and review cycles, farmer level

experimentation, CRA practices refinement, local food systems development,

water and resource conservation access and management and participation and

sharing in and across villages.

b.Innovation Platforms (IP): Clusters of LGs learn and share together with local

and regional stakeholders for knowledge mediation and co-creation and

engagement of Government Departments and officials (1-2 sessions annually

for each IP)

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Development of CbCCA frameworks,

implementation processes (including for example linkages to IDPS and disaster

risk reduction planning and implementation at DM and LM level), reporting

frameworks for the NDC to the CCA strategy, consideration ofmodels for

measurement of resilience and impact (1- 2 sessions annually for each multi

stakeholder platform)

4.Cyclical implementation for all three CoP levels (information provision and sharing,

analysis, action, and review) within the following thematic focus areas: Climate resilient

agriculture practices, smallholder microfinance options, local food systems and

marketing and community owned water and resources access and conservation

management plans and processes. Each of these thematic areas is to be led by one of

the senior researchers and a small sub-team.

5.Monitoring and evaluation: Consisting of the following broad actions:

a.Focus on 3-4 main quantitative indicators e.g. water productivity, production

yields, soil organic carbon and soil health

b.Indicator development for resilience and impact and

c.Exploration of further useful models to develop an overarching framework.

6.Production of synthesis reports, handbooks and process manuals emanating from steps

1-4 withthe primary aim of dissemination of information.

7.And refinement of the CbCCA decision support platform, incorporating updated data

sets and further information form this research and dissemination process.

7

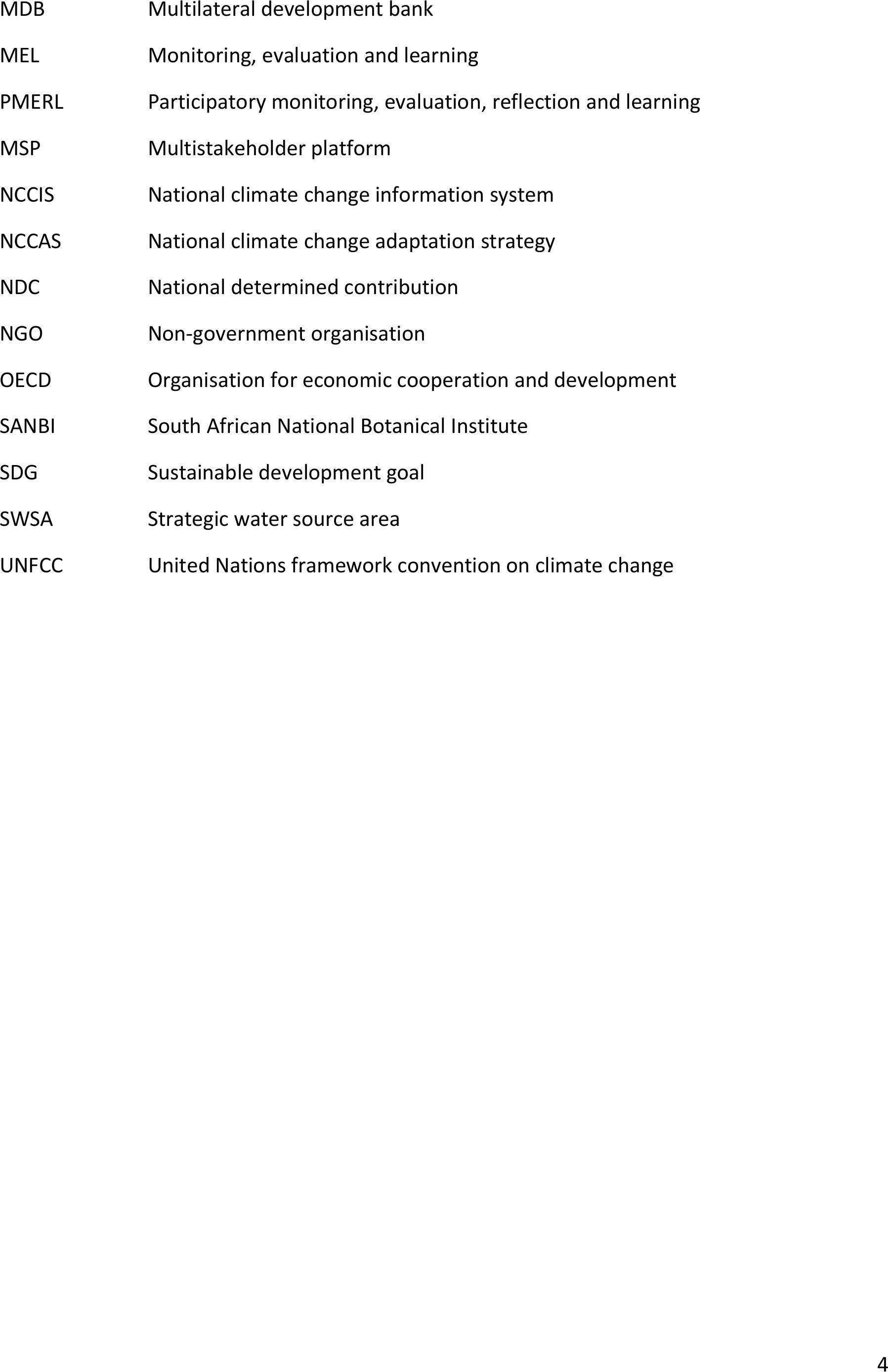

DELIVERABLES

N

o.

Deliverable Title

Description

Target Date

Amount

1

Desk top review for CbCCA

in South Africa

Desk top review of South African policy,

implementation frameworks and

stakeholder platforms for CCA.

01/Aug/2022

R100 000,00

2

Report: Monitoring

framework, ratified by

multiple stakeholders

Exploration of appropriate monitoring

tools to suite the contextual needs for

evidence-based planning and

implementation.

02/Dec/2022

R100 000,00

3

Handbook on scenarios and

options for successful

smallholder financial

services within the South

Africa

Summarize VSLA interventions in SA,

Govt and Non-Govt and design best bet

implementation process for smallholder

microfinance options.

28/Feb/2022

R100000,00

4

Development of CoPs and

multi stakeholder platforms

Design development parameters, roles

and implementation frameworks for CoPs

at all levels, CRA learning groups,

Innovation and multi stakeholder

platforms; within the CbCCA framework.

04/Aug/2023

R133000,00

5

Report: Local food systems

and marketing strategies

contextualized - Guidelines

for implementation

Guidelines and case studies for building

resilience in local food systems and local

marketing strategies towards sustainable

local food systems (local value chain)

08/Dec/2023

R133000,00

6

Case studies: encouraging

community ownership of

water and natural resources

access and management

Case studies (x3) towardsproviding an

evidence base for encouraging community

ownership of natural resource

management through bottom-up

approaches and institutional recognition

of these processes.

28/Feb/2024

R134000,00

7

Case studies: CbCCA

implementation case studies

in 3 different agroecological

zones in SA

CbCCA implementation case studies in 3

different agroecological zones within

South Africa

12/Aug/2024

R133000,00

8

Refined CbCCA decision

support framework with

updated databases and CRA

practices

Refined CbCCA DSS database and

methodology with inclusion of further

viable and appropriate CRA practices

13/Dec/2024

R133000,00

9

Manual for implementation

of successful

multistakeholder platforms

in CbCCA

Methodology and process manual for

successful multi stakeholder platform

development in CbCCA

28/Feb/2025

R134000,00

1

0

Final Report

Final report: Summary of all findings,

guidelines and case studies, learning and

recommendations

18/Aug/2025

(Feb 2026)

R400000,00

8

Deliverable 2, follows on from Deliverable 1 focusing on:

ØDevelopment ofa coherent methodology for multistakeholder engagement, based on

theoretical underpinnings and recent evaluative case studies of successful

multistakeholder processes and platforms

ØExploration of appropriate monitoring tools to suite the contextual needs for evidence-

based planning and implementationincluding:

oModels for measurement of resilience and impact (within multi-stakeholder

platforms)

oIndicator development for resilience and impact

ØExploration of further useful models to develop an overarching framework.

2.CLIMATE RESILIENCE MONITORING TOOLS AND INDICATORS

A resounding call for evidence-basedmeasurements(both qualitative and quantitative)of the

impact of interventionsandprocesses in climatechange adaptation to climate resiliencecan be

heard across sectors. While the primary emphasis globally is on the governmental contributions,

commitments and flows of finances a broad range of other institutional role players have been

grappling with the need for and possibility of a synergised framework for monitoring and

evaluation. Given the wide range of methodological approaches from top-down to locally led

adaptation and the different contexts for implementation this has been a complicated and

confusing task.

For the purposes of this research brief a framework needs to be outlined, which is both globally

and nationally aligned to ensure the widest applicability for the climate resilience metrics

chosen. The work undertaken by the Global Commission on Adaptation (GCA) is used as a global

reference point. For the South African comparison, the National Climate Change Adaptation

Strategy(NCCAS)forms the main reference point. In addition,a few specific examples of

indicator /metric frameworks are provided from different sources:

ØA brief analysis of the Adaptation Fund metrics is to be provided, given that SANBI is the

main implementing agent of this fund for South Africa and has developed protocols for

monitoring and evaluation for the fund itself and also for projects that have been

supported.

ØThe committee on sustainable assessment (COSA), which is a non-profitindependent

global consortium have developed indicator libraries, including one for resilience

indicators. COSA indicators are always aligned with global norms such as the SDGs,

multilateral guidelines, international agreements, and normative references. The

indicators ensure comparability and benchmarking across regions or countries, making

it easier for managers and policymakers. All COSA indicators feature SMART principles:

Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound and Trackable.

9

2.1GLOBAL COMMISSION ON ADAPTATION

The Global Commission on Adaptation was launched in The Haguein 2018 by the United Nations

and the leaders of 22 other convening countries,including South Africa,with the mandate to

accelerate adaptation by elevating the political visibility of adaptation and focusing on concrete

solutionsand finalised its recommendations in 2020. The work is being taken forward by the

Global Centre on Adaptation, with the primary aim to monitor cooperative adaptation action of

non-state actorsand foster community collaboration and knowledge exchange(Global

Commission on Adaptation, 2019) .

While climate mitigation is the ultimate imperative, carefully selected adaptation options

specific to national contexts are equally important and will yield strong co-benefits to sustain

development and reduce poverty. According to the Global Commission on Adaptation, investing

US$1.8 trillion globally between 2020 and 2030 in early warning systems, climate-resilient

infrastructure, improved dryland agriculture crop production, global mangrove protection, and

investments to make water resources more resilient could generate US$7.1 trillion in total net

benefits. The commission also argues that adaptation actions have a triple dividend:

1. Avoided losses

2. Positive economic benefits: reduced risks, increased productivity, and innovation and

3. Social and environmental benefit.

Climate resilience metrics(measures/indicators)will be key to assessing the extent to which

adaptation financing activities and flows contribute to climate resilience and align with the goals

of the Paris Agreement.

Multilateral Development Banks(MDBs) and the international finance community have

developed a process for aligning adaptation indicators with the COP 24 Paris agreement of 2018.

The MDBs’ approach is based on six building blocks that have been identified as the core areas

for alignment with the objectives of theParis Agreement. A joint MDB working group is

developing methods and tools to operationalize this effort under each of the building blocks,

which includes the mitigation and adaptation goals, accelerated contributions to the transition

through climate finance of the different countries’ NDCs, policy development support, reporting

and internal alignment.

a.Principles for climate resilience metrics

Climate resilience metrics complement adaptation finance tracking through a broad and flexible

approach that reflects the great heterogeneity and diversity of climate vulnerability contexts

and of potentially appropriate financing responses. The climate resilience metrics framework is

a flexible structure based on a logical model and results chain. It guides the development of

climate resilience metrics for individual assets and systems, and for financing portfolios, on two

levels:

ØQuality of project design (diagnostics, inputs, activities)

10

ØProject results (outputs, outcomes, impacts)

The framework is underpinned by four core concepts to develop climate resilience metrics and

functional characteristics of those metricswhich reflect the need for:

1. A context-specific approachto climate resilience metrics

2. Compatibility with the variable and often long timescalesassociated with climate

change impacts and building climate resilience

3. An explicit understanding of the inherent uncertaintiesassociated with future climate

conditions, and

4. The ability to cope with the challengesassociated with determining the boundaries

of climate resilience project.

These metrics can serve as a way of documenting more systematically climate resilience efforts

and identify successful examples. In doing so, they can help also identify opportunities for

further climate resilience support(Inter-American Development Bank, 2019)

To start to define the boundaries, context, timescales and uncertainties in adaptation three key

imperatives; human, environmental and economichave been defined and within these broad

systems namely food, natural environment, water, cities, infrastructure, disaster risk

managementand finance(Global Commission on Adaptation, 2019).

Adapting to climate change while also achieving healthy food for all, mitigating climate change,

protecting ecosystems, and achieving the SDGs will require systemic changes to theglobal food

system and global land use.

2.2THE NATIONAL CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION STRATEGY FOR SOUTH AFRICA

In South Africa, The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy was finalised in August 2020

(DFFE, 2020). It outlines the goals, strategic outcomes, activities and timelines and expected

impacts nationally, as well as theresponsibilities and actions of all relevant government

structures, nationally, provincially, and at municipal level. Despite the various efforts on

vulnerability and response plan development, there is no agreed vulnerability and resilience

methodology framework to provide guidance to this process.

Nevertheless, amonitoring and evaluation (M&E) system is in development by DFFE. The M&E

system will focus on tracking the outcomes and impact of each strategic outcome together with

the associated actions and indicators under each strategic outcome. The information/data

collected through M&E will be analysed and profiled on the Climate Change Information System.

The National Climate Change Information System (NCCIS) was recently launched and is part of

the national effort to track South Africa’s overall transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient

economy as required by the National Development Plan (Vision 2030) and the National Climate

Change Response Policy (2011) as well as South Africa’s Nationally Determined Contributions

(2015) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The NCCIS

offers a series of methodologies and decision-support tools that can be used to enhance

11

tracking, assessment,and communication of the effects of climate action response policies and

actions in an accurate, consistent and transparent manner at all scales of implementation to

inform policy and decision making.

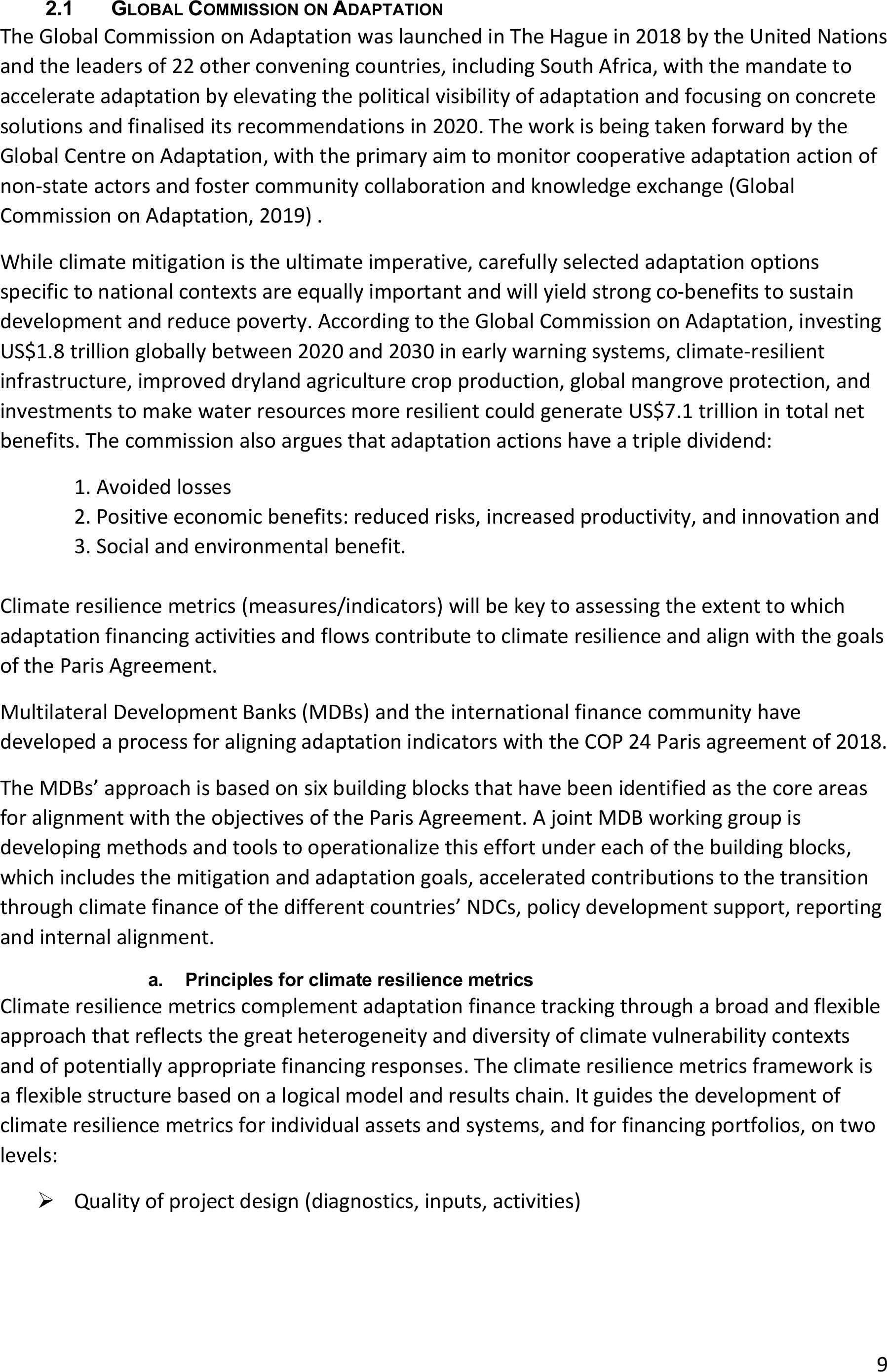

The Climate Change Adaptation Monitoring and Evaluation approach for South Africa has been

organised into nine Desired Adaptation Outcomes (DAOs). Each is of cross-cutting, cross-sectoral

relevance and describes, in a general sense, a desired state that will enhance South Africa’s

transition towards climate resilience. These DAOs fall into two distinct groupsand areshown in

the table below.

Inputs to enable effective adaptation

G1

Robust/integrated policies, programmes and plans for effective delivery of climate change adaptation,

together with monitoring, evaluation and review over the short, medium and longer term

G2

Appropriate resources (including current and past financial investments), capacity and processes (human,

legal and regulatory) and support mechanisms (institutional and governance structures) to facilitate climate

change adaptation

G3

Accurate climate information (e.g.,historical trend data, seasonal predictions, future projections, and early

warning of extreme weather and other climate-related events) provided by existing and new monitoring and

forecasting facilities/networks (including their maintenance and enhancement) to inform adaptation

planning and disaster risk reduction

G4

Capacity development, education,and awareness programmes (formal and informal) for climate change

adaptation (for example informed by adaptation research and with tools to utilise data/outputs).

G5

New and adapted technologies, knowledge, research and other cost-effective measures (for example

nature-based solutions) used in climate change adaptation

G6

Climate change risks, impacts and vulnerabilities identified and addressed.

Impacts of adaptation interventions and associated measures

G7

Systems, infrastructure, communities and sectors less vulnerable to climate change impacts (for example,

through effectiveness of adaptation interventions/response measures)

G8

Non-climate pressures and threats to human and natural systems reduced (particularly where these

compound climate change impacts)

G9

Secure food, water and energy supplies for all citizens (within the context of climate change and sustainable

development).

(FromNCCAS, 2020)

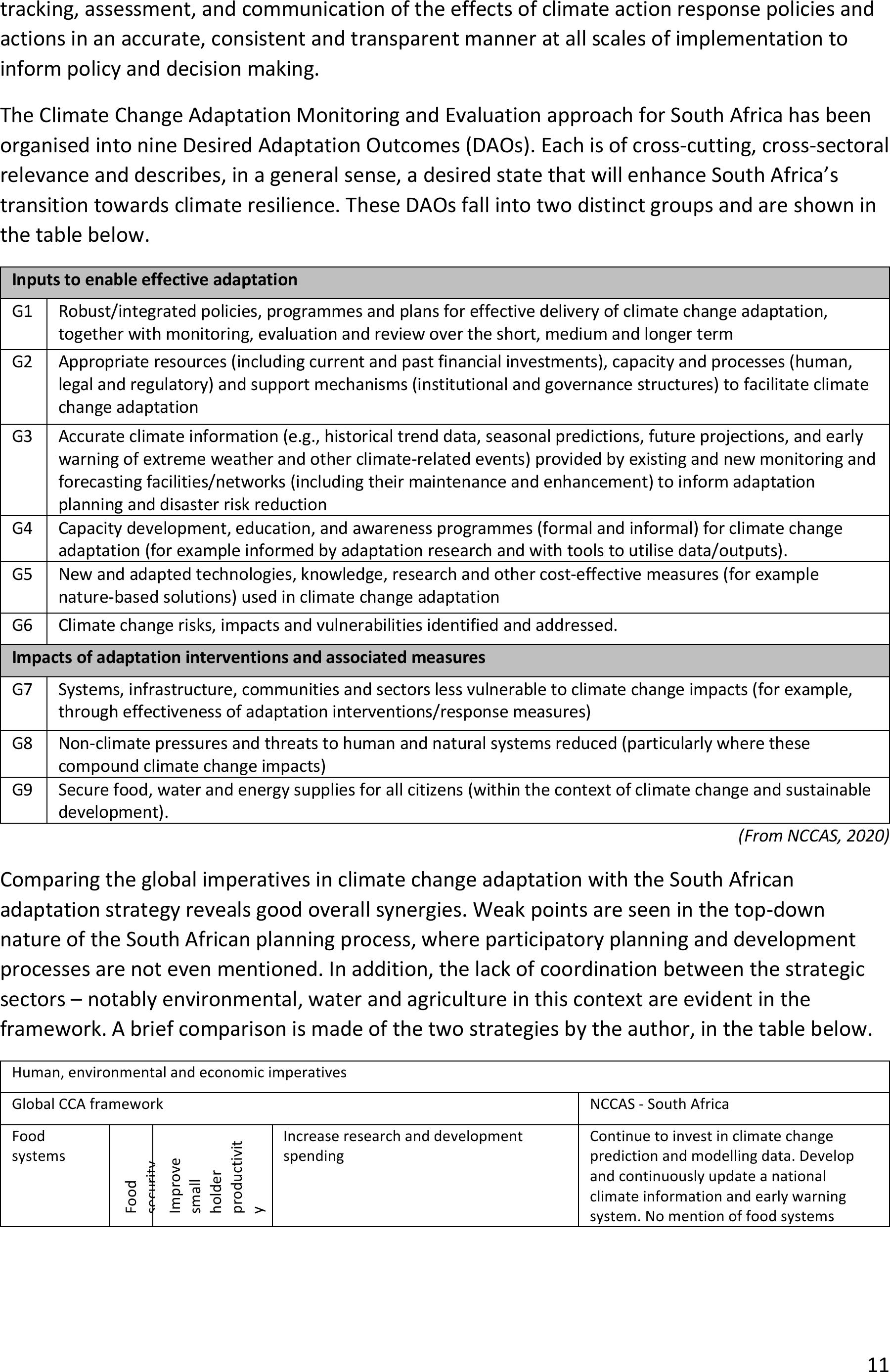

Comparing the global imperatives in climate change adaptation with the South African

adaptation strategy reveals good overall synergies. Weak points are seen in the top-down

nature of the South African planning process, where participatory planning and development

processes are not even mentioned. In addition, the lack of coordination between the strategic

sectors – notably environmental, water and agriculture in this context are evident in the

framework. A brief comparison is made of the two strategies by the author, in the table below.

Human, environmental and economic imperatives

Global CCA framework

NCCAS - South Africa

Food

systems

Food

security

and

livelihoods

of small-

scale

producers

Improve

small

holder

productivit

y

Increase research and development

spending

Continue to invest in climate change

prediction and modelling data.Develop

and continuously update a national

climate information and early warning

system. No mention of food systems

12

Improved extension: weather services,

digital technology, farmer to farmer,

Framed as knowledge and capacity

building.No focus on participatory or

farmer level process, but enhancement of

the role of agricultural extension officers

in supporting the mostvulnerable farmers

is included

Seed systems: protect genetic diversity,

develop new varieties, distribution

systems

Not included present

Help farmers manage increased

climate variability and shocks

Income diversification including farm

diversification, increased market access,

and increased off-farm diversification

Investigate the potential for expanding

sectors and kick-starting new industries

that are likely to thrive as a direct or

indirect result of climate change effects

Stronger social security systems

Identify individuals and communities at

most risk from climate change within

municipalities and deliver targeted climate

change vulnerability reduction

programmes for these individuals and

communities Inclusion of effectivesaving

methodologies and financial education in

training curricula

Bundled livestock/crop insurance

Address the

challenges of

most affected

and

vulnerable

farmers

Improve the rights and resource access of

women farmers

Help pastoralists adapt via flexible

combinations of policies and practices

Implement transition funds

Achieve policy coherence

among food system goals

Redirect public support to promote &

facilitate climate smart agriculture

Framed as implementation of climate

smart and conservation agriculture

practices, expansion of food garden

programmes outside of land classified as

agricultural land

Support synergies and minimize trade-offs

between adaptation & mitigation

Conserve land & water resources at the

landscape scale via improved agronomic

practices and eco-agricultural approaches

Natural

Environment

Harness the power of nature

Accelerate existing actions

Identify, assess, and value natural assets

for their potential to support adaptation

and resilience.

Conduct research into the value of

ecosystem services and the economic

benefits of restoring these services in

comparison to the development of hard

infrastructure

Develop high-level spatial plans to identify

strategic opportunities at larger scales

and to create shared visions for climate-

resilient landscapes

Not in the NAS, but being implemented

through DFFE,SANBI,DWS and NGOs.

Participatory planning processes

Only mentioned as intergovernmental and

departmental collaboration

Increase investment in

nature-

based solutions

National and local governments to

reorient policies, subsidies,and

investments, including developing

programs to better mobilize private

sector support

Framed as awareness raising and re-

orientation rather than subsidies and

investments

Increase resources and technical

assistance for developing countries to

support nature-based adaptation

measures at scale.

Adopt climate resilient approaches to

natural resource management to restore

and maintain ecosystem goods and

services

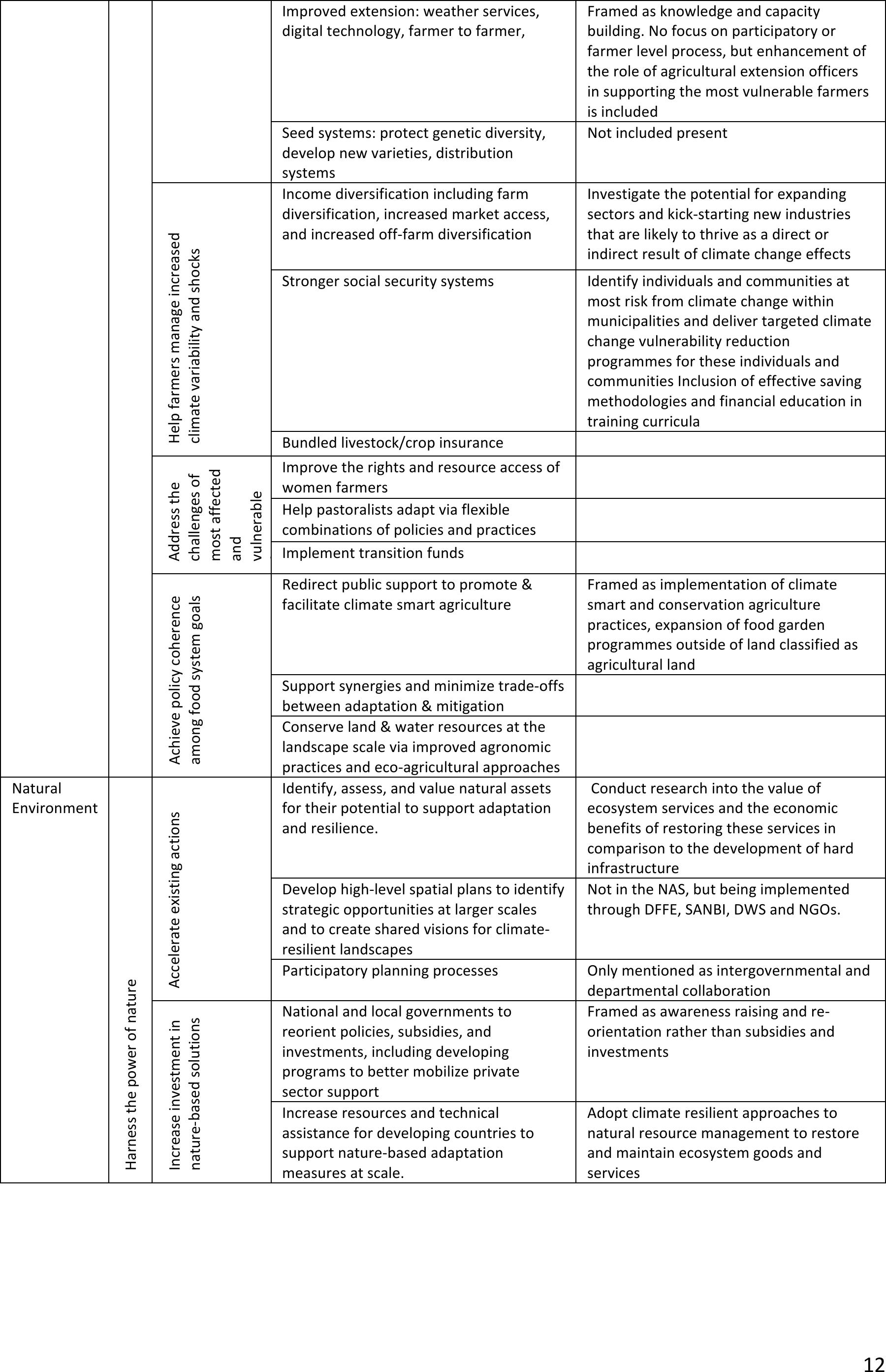

13

Water

Manage water better

Harness the power of

nature and expand water

infrastructure

Invest in healthy watersheds; forests,

wetlands, cities

Protect and conserve South Africa’s most

vulnerable ecosystems, landscapes and

wildlife and monitor and control the

spread of alien invasives. Monitor and

control the spread of invasive alien species

that benefit from climate change.

Promote the expansionof tree cover,

forests and plantations

Enhance and expand water infrastructure

Cope with water

scarcity by using

water more

productively

Reallocate water to societies' highest

priorities

Ensure that water management

institutions incorporate adaptive

management responses

Water smart cities

Adopt water-wise water management

practices in urban areas

Agricultural water use efficiency

Support farmers to use and manage water

more sustainably

Plan for

floods and

droughts

Improve planning at all government levels

including better water monitoring

systems

Capacitate and operationalise South

Africa’s National Disaster Management

Framework to strengthen proactive

climate change adaptive capacity,

preparedness, response and recovery

Improve

water

governance

Improved collaboration among

government agencies

Capacity to develop and implement good

planning and regulatory regimes

Support transboundary water security

Finance

Scale up

financing

systems

Governments should arrange for major

increases in financing. Investments in

stormwater management, infrastructure

to reduce flood and drought risk, and

ecosystem protection

(From GCA 2019, NCCAS, 2020)

Development of a framework for resilience indicatorsdepends on the basic point or departure,

assumptions and theory of change that is in place, as well as the definition of resilience that is

being used.

b.SANBI: Adaptation Fund

The Adaptation Fund(AF)was established through decisions by the Parties to the United

Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change and its Kyoto Protocol to finance concrete

adaptation projects and programs in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the

adverse effects of climate change. The South African National Botanical Institute (SANBI) is the

national implementing entity (NEI) for South Africa. SANBI implements the evaluation policy of

the adaptation fund. The purpose of this Evaluation Policy (EP) is to identify the fundamental

expectations, processes, andprotocol to support a reliable, useful, and ethical evaluation

function thatcontributes to learning, decision-making, and accountability for the Adaptation

Fund to pursue its mission, goal, and vision effectively (AF-TERG, 2022).The Fund’s instruments

that are dedicated to monitoring include the results-based management (RBM) system and

Strategic Results Framework (SRF). The Fund prioritizesmonitoring, evaluation and learning

(MEL) because “learning for effective adaptation” is a central tenet of the Fund’s mission, which

14

is reinforced by its strategic focus of learning and sharing to ensure the Fund remains effective,

efficient, and fit for purpose.

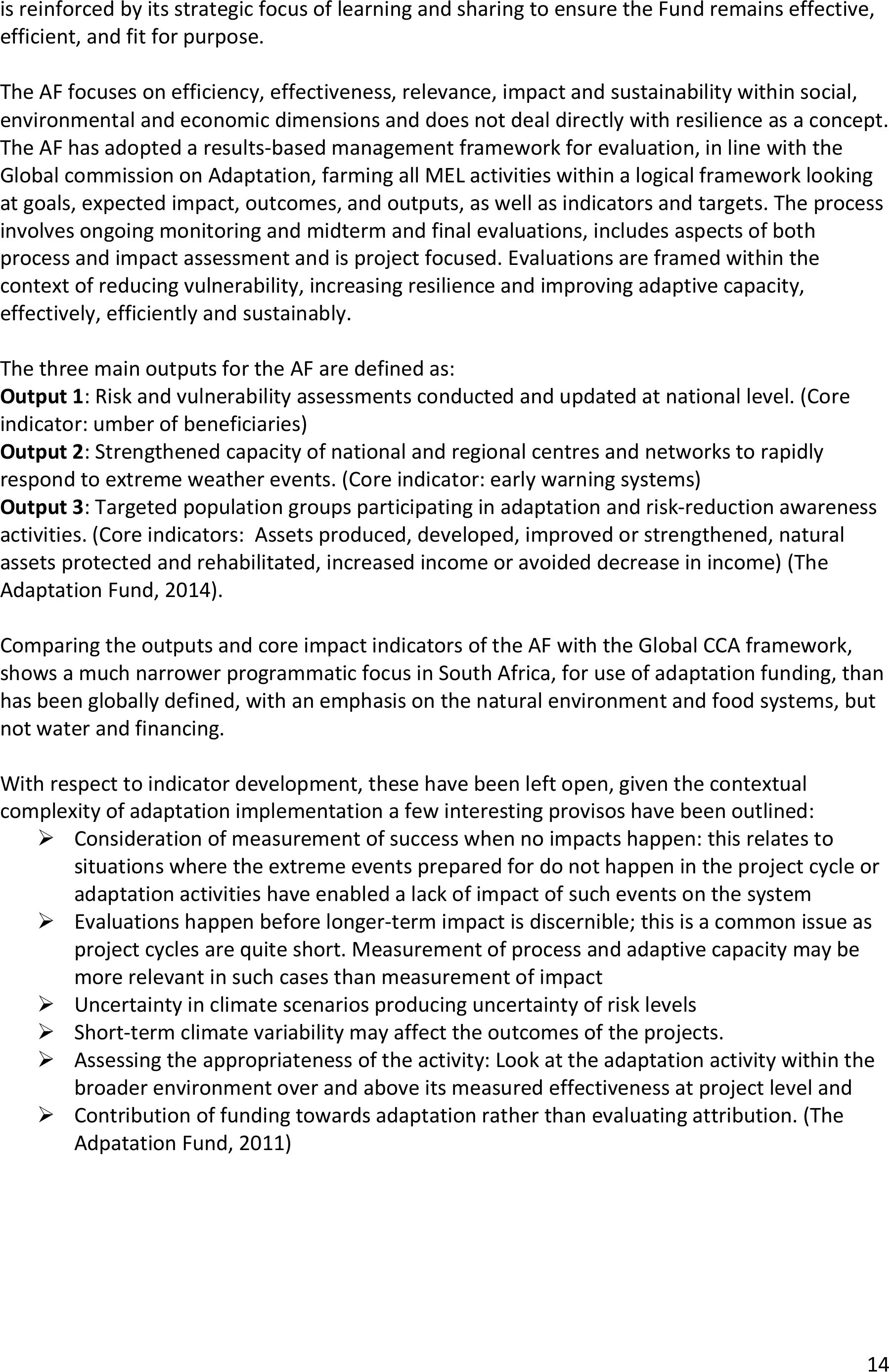

The AF focuses on efficiency, effectiveness, relevance, impact and sustainability within social,

environmental and economic dimensions and does not deal directly with resilience as a concept.

The AF has adopted a results-based management framework for evaluation, in line with the

Globalcommission on Adaptation, farming all MEL activities within a logical framework looking

at goals, expected impact, outcomes, and outputs, as well as indicators and targets.The process

involves ongoing monitoring and midterm and final evaluations, includes aspects of both

process and impact assessment and is project focused. Evaluations are framed within the

context of reducing vulnerability, increasing resilience and improving adaptive capacity,

effectively, efficiently and sustainably.

The three main outputs for the AF are defined as:

Output 1: Risk and vulnerability assessments conducted and updated at national level.(Core

indicator: umber of beneficiaries)

Output 2: Strengthened capacity of national and regional centres and networks to rapidly

respond to extreme weather events.(Core indicator: early warning systems)

Output 3: Targeted population groups participating in adaptation and risk-reduction awareness

activities.(Core indicators: Assets produced, developed, improved or strengthened, natural

assets protected and rehabilitated, increased income or avoided decrease in income) (The

Adaptation Fund, 2014).

Comparing the outputs and core impact indicators of the AF with the Global CCA framework,

showsa much narrower programmatic focus in South Africa, for use of adaptation funding, than

has been globally defined, with an emphasis on the natural environment and food systems, but

not water and financing.

With respect to indicator development, these have been left open, given the contextual

complexity of adaptation implementation a few interesting provisos have been outlined:

ØConsideration of measurement of success when no impacts happen: this relates to

situations where the extreme events prepared for do not happen in the project cycle or

adaptation activities have enabled a lack of impact of such events on the system

ØEvaluations happen before longer-term impact is discernible; this is a common issue as

project cycles are quite short. Measurementof process and adaptive capacity may be

more relevant in such cases than measurement of impact

ØUncertainty in climate scenarios producing uncertainty of risk levels

ØShort-term climate variability may affect the outcomes of the projects.

ØAssessing the appropriateness of the activity: Look at the adaptation activity within the

broader environment over and above itsmeasured effectivenessat project leveland

ØContribution of funding towards adaptation rather than evaluating attribution. (The

Adpatation Fund, 2011)

15

c.Committee on Sustainable Assessment (COSA) resilience indicators

The idea of resilience, particularly as a programming tool in response to disaster and climate-

change phenomena, has become increasingly prevalent in international development. Given the

widespread use of the terminology in various fields and by various technical and non-technical

actors, it is important to present a synthesized view of resilience and create a common language

to advance core terms. It is particularly important to translate high-level concepts of resilience

into actionable measurement metrics in order to implement, monitor, and evaluate resilience

programs

The COSA resilience measurement approach builds on the best current work to distil the optimal

practices into a pragmatic and relatively low-cost process that permits a solid basic

understanding while increasing broad access to these simpler tools (COSA, 2017)

The approach used to classify the indicators balances a multi-dimensional view based on

dynamic resilience capacities (adaptive, absorptive, and transformative) with static social,

environmental, and economic (SEE) dimensions (shown in text box: Indicators classification)in

Indicators Classification

Capacity approach:The capacity approach was developed by Béné et al.(Bene, Wood, Newsham, & Davies, 2012)and is

founded on a belief that resilience is a dynamic construct described by three main strategies used to cope with stressors

and shocks: absorptive, adaptive, and transformative.

•Absorptive capacity:This is the ability to reduce both risk of exposure to shocks and stressors and to absorb the

impacts of shocks in the short term. We classify into absorptive capacity all the indicators necessary for risk

prevention and risk mitigation.

•Adaptive capacity: Adaptive capacity is the ability to respond to longer-term social, economic, and

environmental change. We classify all of the proactive choices about alternative livelihood strategies in light of

changing conditions into adaptive capacity.

•Transformative capacity: Transformative capacity represents the ability to enhance governance and enable

conditions that make households and communities more resilient. In other words, transformative capacity

refers to system-level changes that enable a more lasting resilience.

Capital approach:The capital approachis founded on a belief that people require a range of assets to achieve positive

livelihood outcomes. The Sustainable Livelihood Framework (DFID, 2000) inspired this vision.

•Human capitalincludes indicators referring to skills, knowledge, ability to work, and good health that are

important to the pursuit of livelihood strategies.

•Socio-political capitalincludes the quantity and quality of social resources (e.g., networks, membership in

groups, social relations, and access to wider institutions in society) from which people draw in pursuit of their

livelihoods. It encapsulates good governance indicators.

•Natural capitalincludes all indicators that represent factors affecting households’ livelihoods through climate

changevariables (e.g., adaptation, mitigation, and sequestration practices) and through the humanactivity

•Physical capital includes infrastructure, services, and productive assets that enable people to maintain safety

and enhance their relative level of well-being.

•Financial capitalincludes all indicators referring to the financial resourcesthathouseholds use to achieve their

economic and social objectives. It includes cash. and other liquid resources, (e.g., savings, credit, remittances,

pensions).

16

order tocapture the complexity of factors relevant to measuring agricultural resilience. SEE

elements are in turn disaggregated into commonly accepted capitals (human, physical, socio-

political, financial, natural) of a resilience measurement system in line with the Sustainable

Livelihood Framework devised by the Department for International Development (DIFD, 2000).

The lessons learned from the field allowed COSA to define a set of Resilience Key Performance

Indicators (R-KPIs) to create pragmatic knowledge on critical aspects of resilience and to address

two main issues of the current resilience approaches: complexity and high implementation

costs.

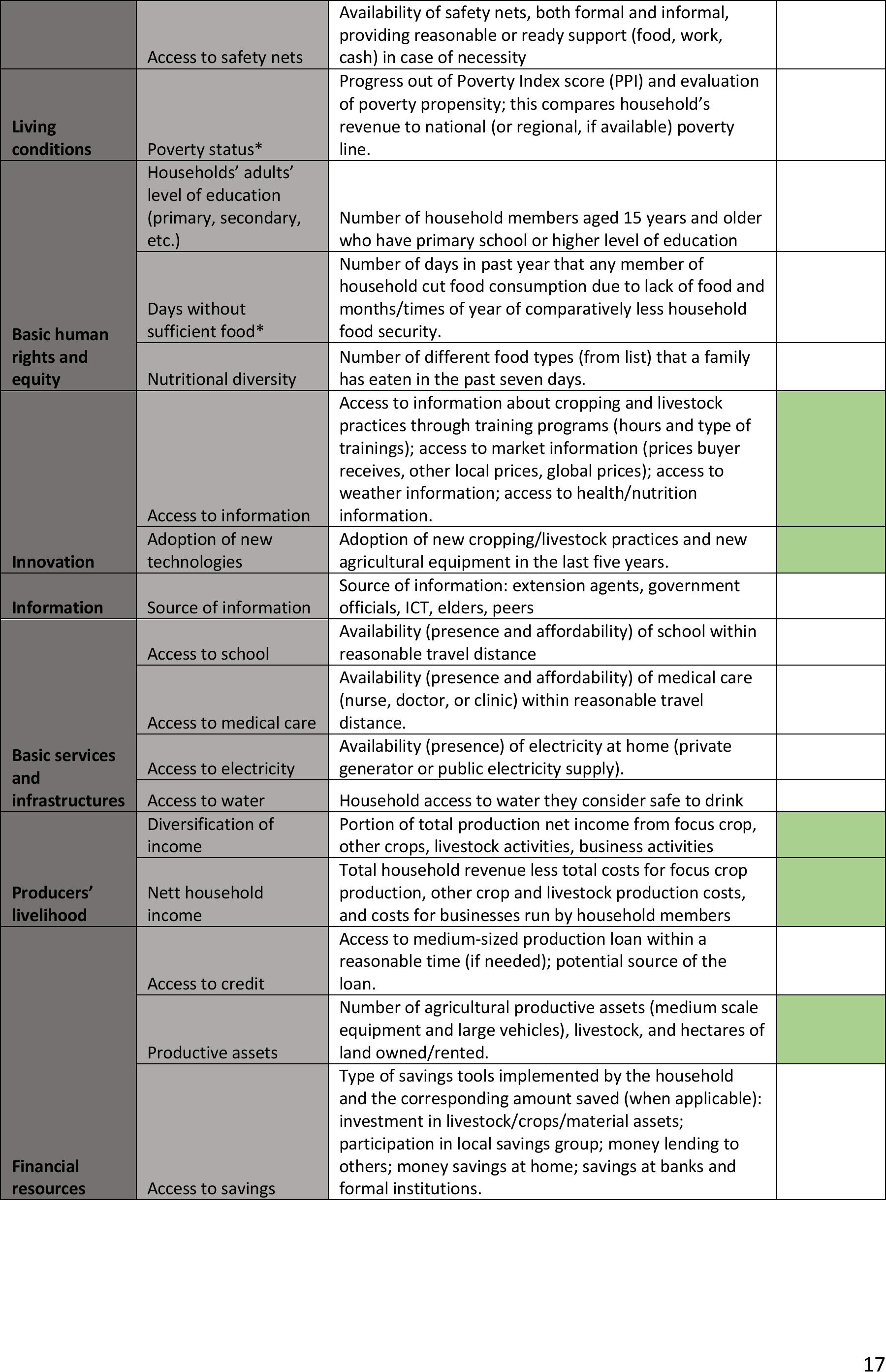

The table below outlines the full set of resilience indicators as outlined by COSA andprovides a

comparison with the indictors used in the AF process.

COSA Resilience indicator library

Adaptation

Fund: Core

indicators

Global theme

Indicator

Description

Shock and risk

Risk context

information

The type of risks at which households are exposed to.

Occurrence and

severity of shocks

Occurrence of three major shocks (social, economic, or

environmental) that led to a serious reduction in

household’s income, assets, or consumption in the last

production year. Shocks ranked in order of severity.

Type of coping

strategies and severity

Type of coping strategies that household applied to face

the main shock experienced in the last production year

(migration, aid, new sources of income, reducing

expenses, using savings).Coping strategies ranked in

order of importance.

Individual

preparedness

strategies

Strategies implemented by the household to face shocks

(stock of feed/seeds, storage of water, measures taken

to overcome leaf rust, new seeds varieties/animal

breeds, irrigation systems).

Recovery ability

Perceived speediness and ability to recover from the

main shock experienced in the last production year

Early warning

systems

Access, source (extension agents, government officials,

ICT), and frequency of critical information about adverse

events. Perceptions about quality of information

Community

and

institutional

environment

Perceptions around

political environment

Perceptions about accountability and transparency of

political process, feeling of safety in community life, and

trust in institutions.

Participation in

decision making

structures

Involvement and participation of household and

minority groups (women, youth) in decision-making

structures (village councils, tribal council, producer

organizations).

Participation in

community activities

Involvement and participation of household members in

community activities (improvements in agricultural

facilities, access to water or sewage, medical care, road,

or school construction).

Perceptions about

political environment

Perceptions about accountability and transparency of

political process, feeling of safety in community life, and

trust in institutions.

17

Access to safety nets

Availability of safety nets, both formal and informal,

providing reasonable or ready support (food, work,

cash) in case of necessity

Living

conditions

Poverty status*

Progress out of Poverty Index score (PPI) and evaluation

of poverty propensity; this compares household’s

revenue to national (or regional, if available) poverty

line.

Basic human

rights and

equity

Households’ adults’

level of education

(primary, secondary,

etc.)

Number of household members aged 15 years and older

who have primary school or higher level of education

Days without

sufficient food*

Number of days in past year that any member of

household cut food consumption due to lack of food and

months/times of year of comparatively less household

food security.

Nutritional diversity

Number of different food types (from list) that a family

has eaten in the past seven days.

Innovation

Access to information

Access to information aboutcropping and livestock

practices through training programs (hours and type of

trainings); access to market information (prices buyer

receives, other local prices, global prices); access to

weather information; access to health/nutrition

information.

Adoption of new

technologies

Adoption of new cropping/livestock practices and new

agricultural equipment in the last five years.

Information

Source of information

Source of information: extension agents, government

officials, ICT, elders, peers

Basic services

and

infrastructures

Access to school

Availability (presence and affordability) of school within

reasonable travel distance

Access to medical care

Availability (presence and affordability) of medical care

(nurse, doctor, or clinic) within reasonable travel

distance.

Access to electricity

Availability (presence) of electricity at home (private

generator or public electricity supply).

Access to water

Household access to water they consider safe to drink

Producers’

livelihood

Diversification of

income

Portion of total production net income from focus crop,

other crops, livestock activities, business activities

Nett household

income

Total household revenue lesstotal costs for focus crop

production, other crop and livestock production costs,

and costs for businesses run by household members

Financial

resources

Access to credit

Access to medium-sized production loan within a

reasonable time (if needed); potential source of the

loan.

Productive assets

Number of agricultural productive assets (medium scale

equipment and large vehicles), livestock, and hectares of

land owned/rented.

Access to savings

Type of savings tools implemented by the household

and the corresponding amount saved (when applicable):

investment in livestock/crops/material assets;

participation in local savings group; money lending to

others; money savings at home; savings at banks and

formal institutions.

18

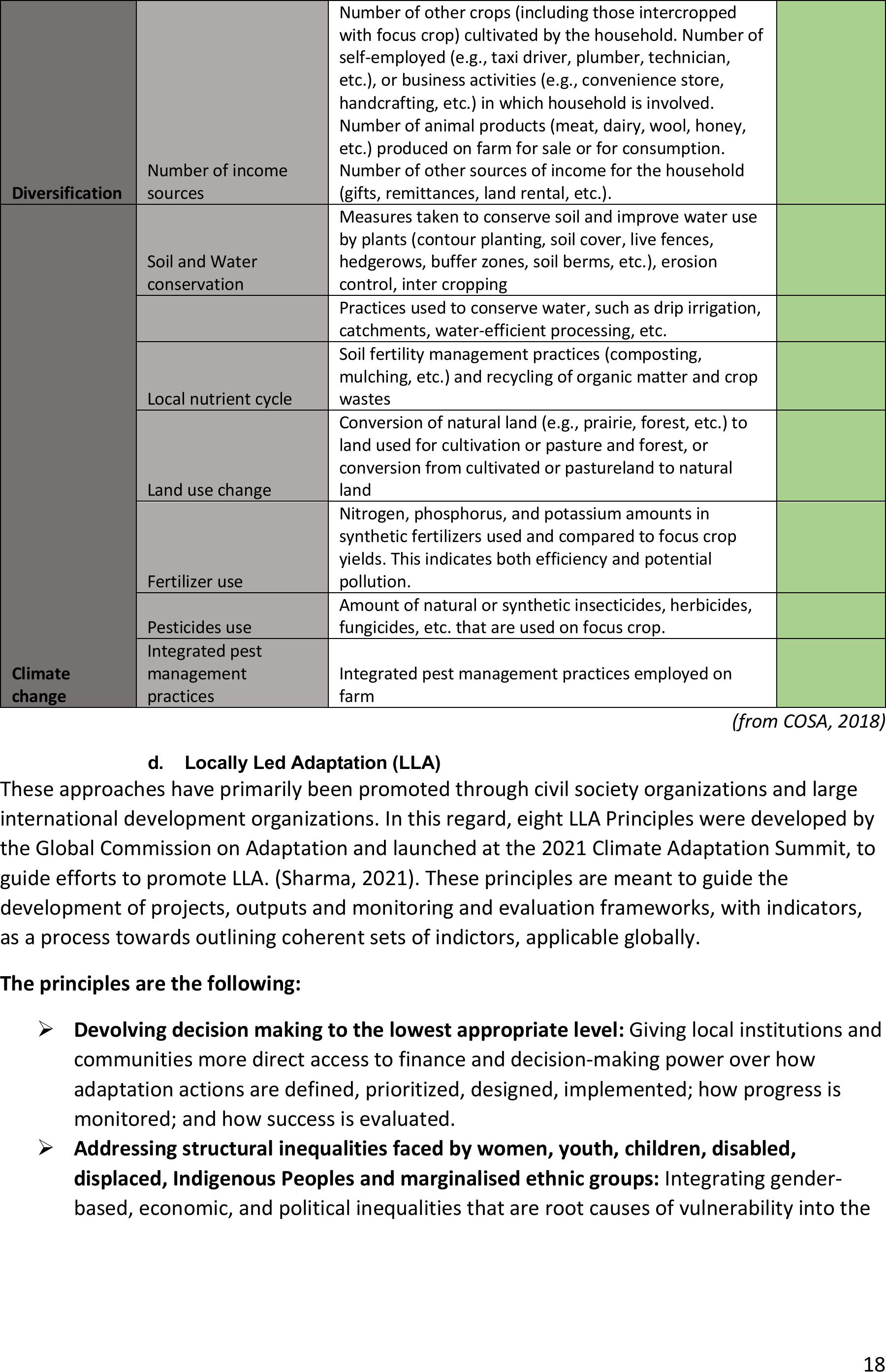

Diversification

Number of income

sources

Number of other crops (including those intercropped

with focus crop) cultivated by the household. Number of

self-employed (e.g., taxi driver, plumber, technician,

etc.), or business activities (e.g., convenience store,

handcrafting, etc.) in which household is involved.

Number of animal products (meat, dairy, wool, honey,

etc.) produced on farm for sale or for consumption.

Number of other sources of income for the household

(gifts, remittances, land rental, etc.).

Climate

change

Soil and Water

conservation

Measures taken to conserve soil and improve water use

by plants (contour planting, soil cover, live fences,

hedgerows, buffer zones, soil berms, etc.), erosion

control, inter cropping

Practices used to conserve water, such as drip irrigation,

catchments, water-efficient processing, etc.

Local nutrient cycle

Soil fertility management practices (composting,

mulching, etc.) and recycling of organic matter and crop

wastes

Land use change

Conversion of natural land (e.g., prairie, forest, etc.) to

land used for cultivation or pasture and forest, or

conversion from cultivated or pasturelandto natural

land

Fertilizer use

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium amounts in

synthetic fertilizers used and compared to focus crop

yields. This indicates both efficiency and potential

pollution.

Pesticides use

Amount of natural or synthetic insecticides, herbicides,

fungicides, etc. that are used on focus crop.

Integrated pest

management

practices

Integrated pest management practices employed on

farm

(from COSA, 2018)

d.Locally Led Adaptation (LLA)

These approaches have primarily been promoted through civil society organizations and large

international development organizations. In this regard,eight LLA Principles were developed by

the Global Commission on Adaptation and launched at the 2021 Climate Adaptation Summit, to

guide efforts to promote LLA.(Sharma, 2021). These principles are meant to guide the

development of projects, outputs and monitoring and evaluation frameworks, with indicators,

as a process towards outlining coherent sets of indictors, applicable globally.

The principles are the following:

ØDevolving decision making to the lowest appropriate level:Giving local institutions and

communities more direct access to finance and decision-making power over how

adaptation actions are defined, prioritized, designed, implemented; how progress is

monitored;and how success is evaluated.

ØAddressing structural inequalities faced by women, youth, children, disabled,

displaced, Indigenous Peoples and marginalised ethnic groups:Integrating gender-

based, economic, and political inequalities that are root causes of vulnerability into the

19

core of adaptation action and encouraging vulnerable and marginalized individuals to

meaningfully participate in and lead adaptation decisions.

ØProviding patient and predictable funding that can be accessed more easily:

Supporting long-term development of local governance processes, capacity, and

institutions through simpler access modalities and longer term and more predictable

funding horizons, to ensure that communities can effectively implement adaptation

actions.

ØInvesting in local capabilities to leave an institutional legacy:Improving the capabilities

of local institutions to ensure they can understand climate risks and uncertainties,

generate solutions, and facilitate and manage adaptation initiatives over the long term

without being dependent on project-baseddonor funding.

ØBuilding a robust understanding of climate risk and uncertainty:Informing adaptation

decisions through a combination of local, traditional, Indigenous, generational and

scientific knowledge that can enable resilience under a range of future climate

scenarios.

ØFlexible programming and learning:Enabling adaptive management to address the

inherent uncertainty in adaptation, especially through robust monitoring and learning

systems, flexible finance, and flexible programming.

ØEnsuring transparency and accountability:Making processes of financing,designing,

and delivering programs more transparent and accountable downward to local

stakeholders.

ØCollaborative action and investment:Collaboration across sectors, initiatives,and levels

to ensure that different initiatives and different sources of funding (humanitarian

assistance, development, disaster risk reduction, green recovery funds, etc.) support

each other, and their activities avoid duplication, to enhance efficiencies and good

practice.

These principles in essence reflect the frameworks described above, but include specific ideas

around devolving decision making, addressing structural inequalities and building local capacity

for action and governance. These are aspects not presently well-defined or incorporated into

the South African CCA thinking and programming. The concepts of adaptive management and

multi stakeholder engagement are important and these are being considered.

This is for example reflected in a recent evaluation of the Small Grants facility of the AF (CA-SGF,

2018). Their learnings, which should now be incorporated into the next round of

implementation emphasize a holistic approach, partnerships at multiple levels, locally driven

processes, adaptive management and capacity enhancement.

20

3.MULTI STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT:TOWARDS A COHERENT METHODOLOGY

There are varies ways in which people or groups come up with solutions for complex situations or

to explore new and promising opportunities that requireworking in partnership. These

partnerships and interactions are expressed in different ways ranging from coalition, alliances,

networks and platforms to participatory governance, stakeholder engagements and interactive

policymaking. The term multi-stakeholder platform (MSP) is an overarching concept for

partnerships highlighting a vision that different groups sharing a common goal can work together

(Surminski & and Leck, 2016). These different groups include government, bothlocal and national,

Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), private sector and

academia(Forino, 2015). They also include local people and communities.

Important considerations for an MSP is inclusion of multiple stakeholders at different levelswith

a shared vision or aim to resolve a complex issue coming together, learning and sharing

knowledge amongst each other in order to reach a collective resolution.

Successful MSPs are observed through the following principles:

-They are able to achieve lasting outcomes

-They involve wide variety of actors

-They have the ability to create sustainableworking groups and

-They work towards finding common solutions. (Thorpe, Guijt, Sprenger, & Darian, 2021)

If these principles are in place, then MSPs have the ability to facilitate and promote policy and

legal reforms, create neutral spacesfor climate and other related issues and promote buy-in for

responsible governance. The manner in which the partnerships are setup, the processes used, the

capacity for leadershipand the skill of facilitationare important underlying considerations for

success.

There are a broad range of multi stakeholder engagement platforms in South Africa and also a

broad range of approaches to such platforms. In this review, the focus will be on the more

recently developed forums in the fields of integrated catchment and water resources

management and on the Adaptation Networkas the one formal and representative national

network/ multistakeholder engagement platform in CCA in South Africa.

a.SANBI Living catchments Project

The Living Catchments Project, a partnership between SANBI, the Water Research Commission

and the Department of Science and Innovation, actively addresses the water related issues in

South Africa, with a focus on ecological infrastructure and water security.

The primary aim of the Living Catchments Project is to create more resilient, better resourced,

and more relational communities at both catchment and national scales, that are able to draw

from the best that the research has to offer in the process of governing the equitable,

21

productive and sustainable use of water resources and ecosystem goods and services, through

strengthening of an enabling environment for catchment governance and the integration of

built and ecological infrastructure in support of water security, economic development and

livelihood improvement (Living Catchments Project, 2022).

Four catchment platforms have been convened, namely the uMzimvubu, Berg-Breede, Olifants

and uThukela catchments. Communities of practise Comprising of traditional leaders, civil

society, rural communities, policy makers, researchers, and practitioners have been set up, each

consisting of a defend membership, vision,and action plan for the respective catchments. The

emphasis is on collaboration, co-learning and co-creation.

The outputs and core indicators for this process are as follows:

Output 1:The CoP builds and nurtures a co-learning and co-creation space to develop a

research and innovation linked agenda for their catchment (Core indicator: Increase diversity of

actors, articulation of research priorities and evidence of sharing)

Output 2: Capacity and tools for work in Strategic Water Source Area catchments is increased

and embedded (Core indicator: Evidence of use of tools in implementation)

Output 3: Learning, circulating of ideas and experience, and expansion of networks is facilitated

through designed encounters (Core indicator: Articulation of learning and evidence of using

approaches and methods from one catchment in another)

Output 4: Social spaces fostering collaboration & co-learning are sustainable and locally

institutionalised (Core indicator: Sustainability of hosting and chairing the CoP) (Letty B. , 2022)

The LCP has pioneered the inclusion of multistakeholder involvement in management and

governance issues related to water and have also developed the first broad based monitoring

process for impact of multistakeholder engagement, related to environmental and water issues

and thus provides a good grounding for further exploration of indicators in this field. This

process is however as yet not touching directly on issues of resilience and adaptation, although

these could be considered to be embedded in the catchment processes to some extent.

b.The uThukela Water Source Forum

Building on the SANBI-LCP and towards establishing a strategic water source area partnership

for the Northern Drakensberg SWA, WWF’s Freshwater programme is supporting the initiation

of a multistakeholder partnership. The convenors for this partnership are The Institute of

Natural Resources, the Centre for Water Resources Research (UZKN) and MDF.

The process is still in the initial stages of participatory development of a vision towards action

and uses the adaptive planning processalong with OECD’s process on multi stakeholder

engagement for water governance(OECD, 2015)as its strategic approach.

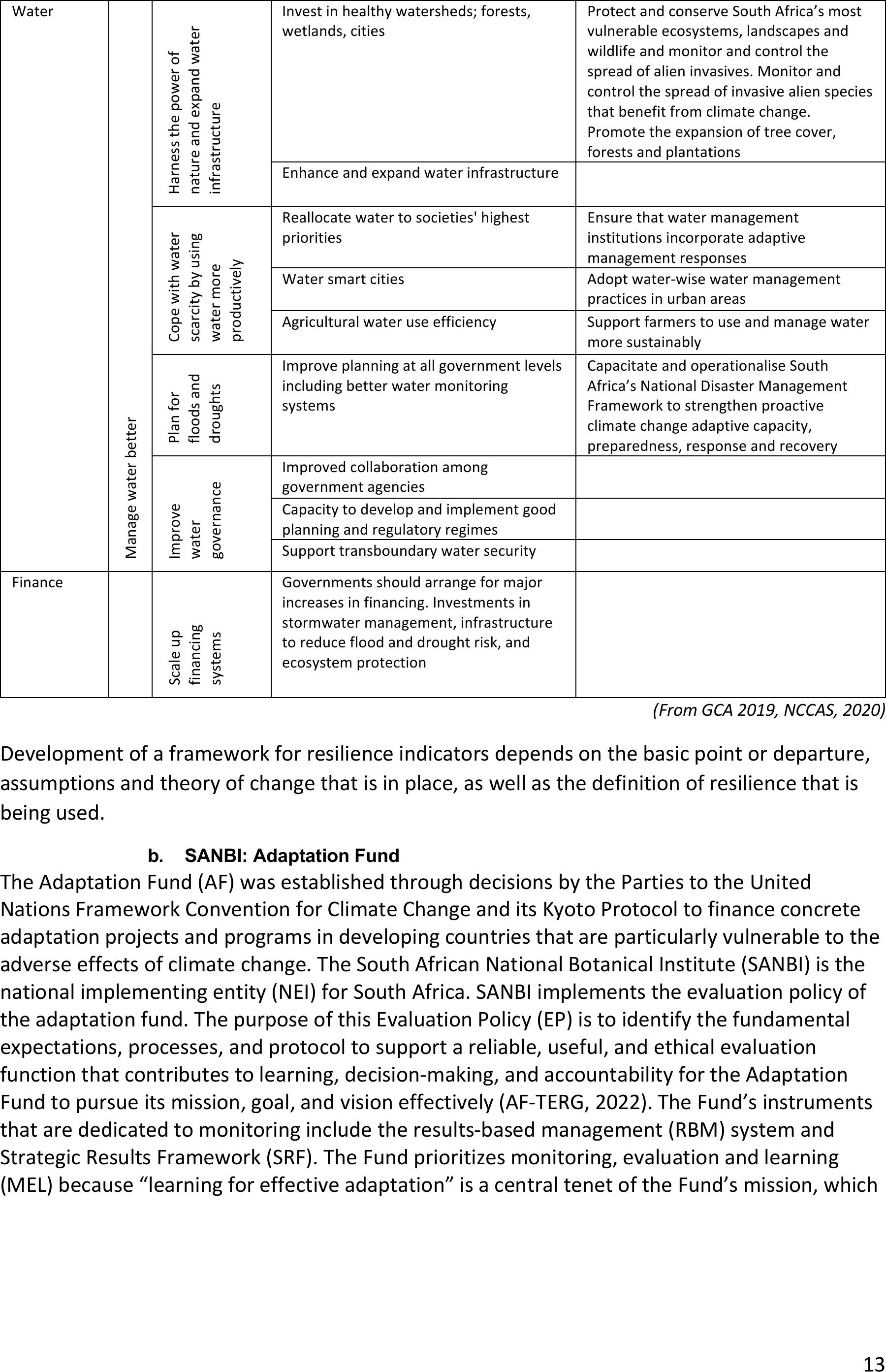

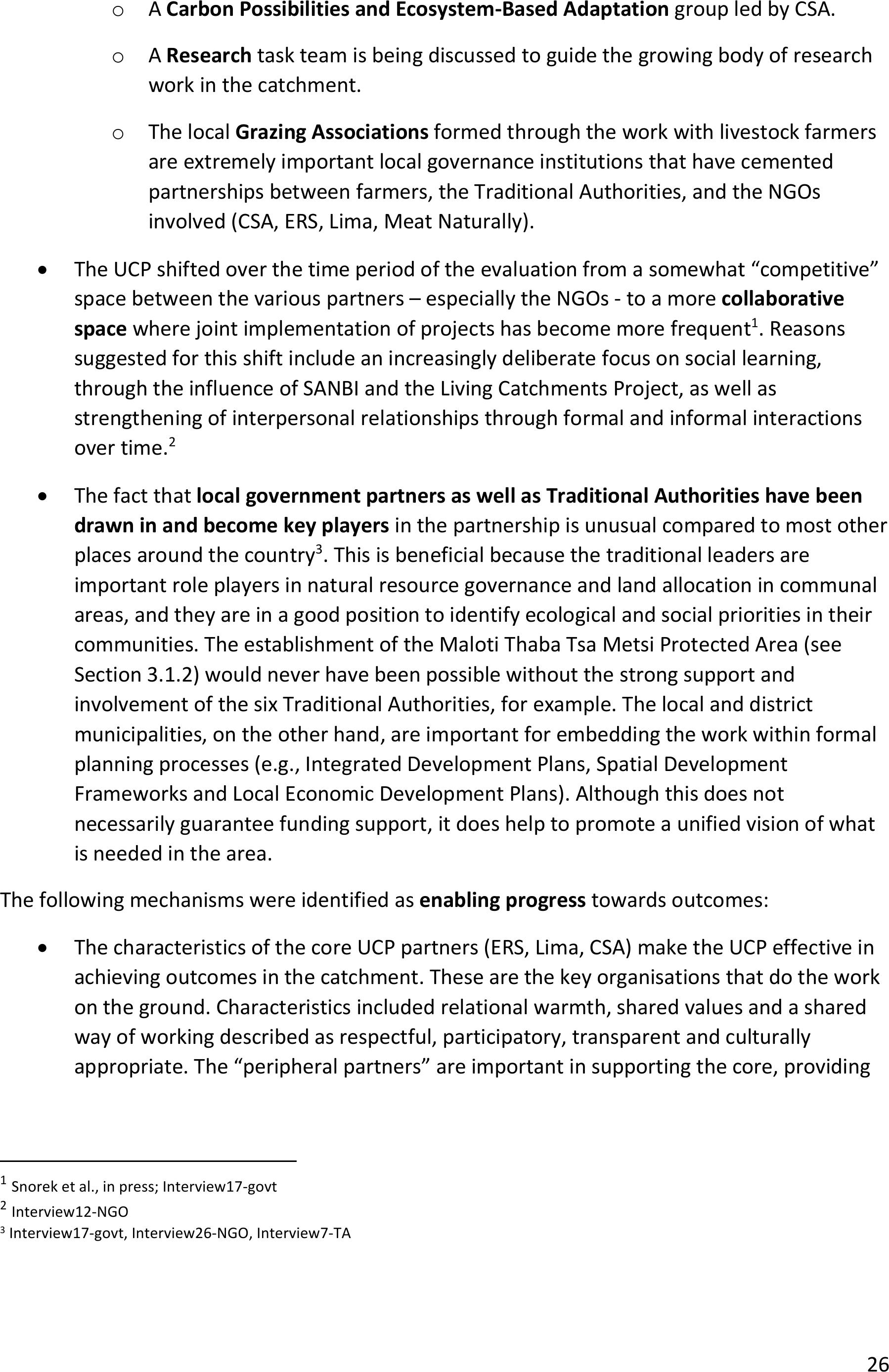

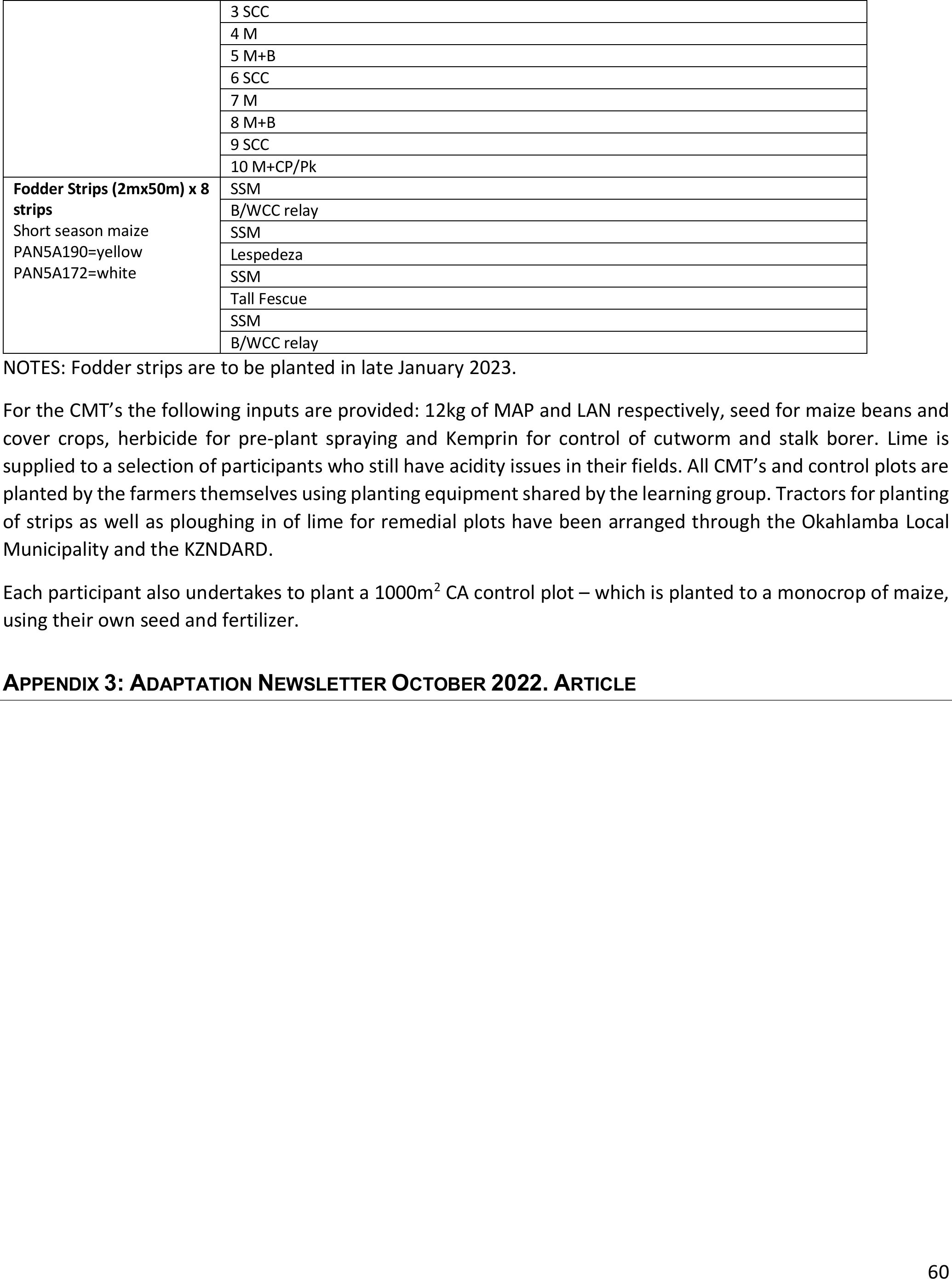

The process for development of an MSP is outlined in the diagram below.

22

Figure 1: Progression for multi stakeholder platforms development (OECD, 2015)

The principles for engagement in development of an MSP and the steps towards achieving

these principles are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Table outlining principles for multi stakeholder engagement and steps in achieving these (OECD, 2015)

Principle

What needs to be done

1.Inclusiveness and equity

Map all SH with a stake or an interest: their responsibilities, interests and

interactions with other SH

2.Clarity of goals, transparency

and accountability

Define decision-making, the objectives of SH engagement and expected use of

input

3.Capacity and information

Allocate proper financial and human resources and information sharing

4.Efficiency and effectiveness

Assess and re-assess the process: Learn, adjust and improve the SH

engagement

5.Institution and structure

Embed engagement processess in legal and policy frameworks, organizational

structures/principles and responsible authorites

6.Adaptivness

Customize the type and level of engagement to the needs and be flexible to

changing circumstances

Between June and November 2022, three multi stakeholder events have been held, in addition

to smaller and face to face interactions with specific organizations towards including as many of

the role players as possible, mapping the stakeholders, outlining their roles and responsibilities

as well as mandates and interests and in starting to define a vision for the partnership.In

addition,collaboration in activities and engagements inthe catchment have been initiated,

primarily around local water access options through spring protection and reticulation (which

has included theWWF,INR, CWRR, MDF, and the Maloti Drakensberg Transfrontier Park (MTDP)

as well as alien clearing and restoration activities (WWF,INR, MDF, Wildlands and MTDP, KZN

Comm

unicati

on

Consultat

ion

Participa

tion

Represe

ntation

Partners

hip

Co-decision

and co-

production

Create and

share

information

Create

awareness

Encourage

action

Gather

perceptions,

information

and

experience

from

stakeholders

(no

commitment

to consider

them)

Provide

opportunities

to take part in

policy/project

processes

(stakeholder

may still not

influence

decision-

making)

Includes

engagement

with

stakeholders

to develop

collective

choices

Agreed upon

collaboration

between

stakeholders

Characterized

by joint

agreement

(may be

formal or

informal)

Balanced share

of power among

stakeholders

involved

Joint decision-

making

23

Wildlife and Conservation South Africa (CSA). The importance of implementation alongside

discussions has been emphasized from the outset.

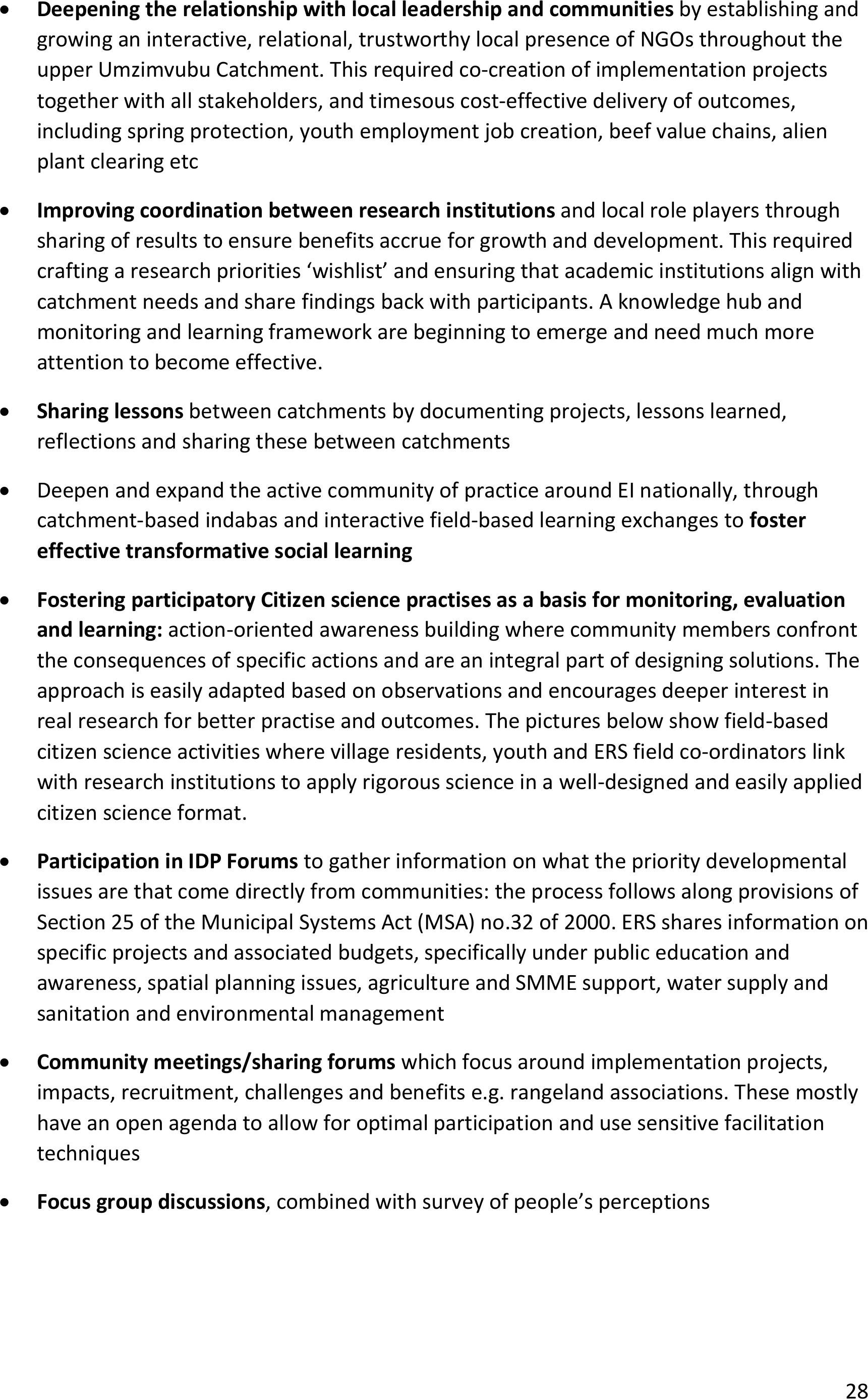

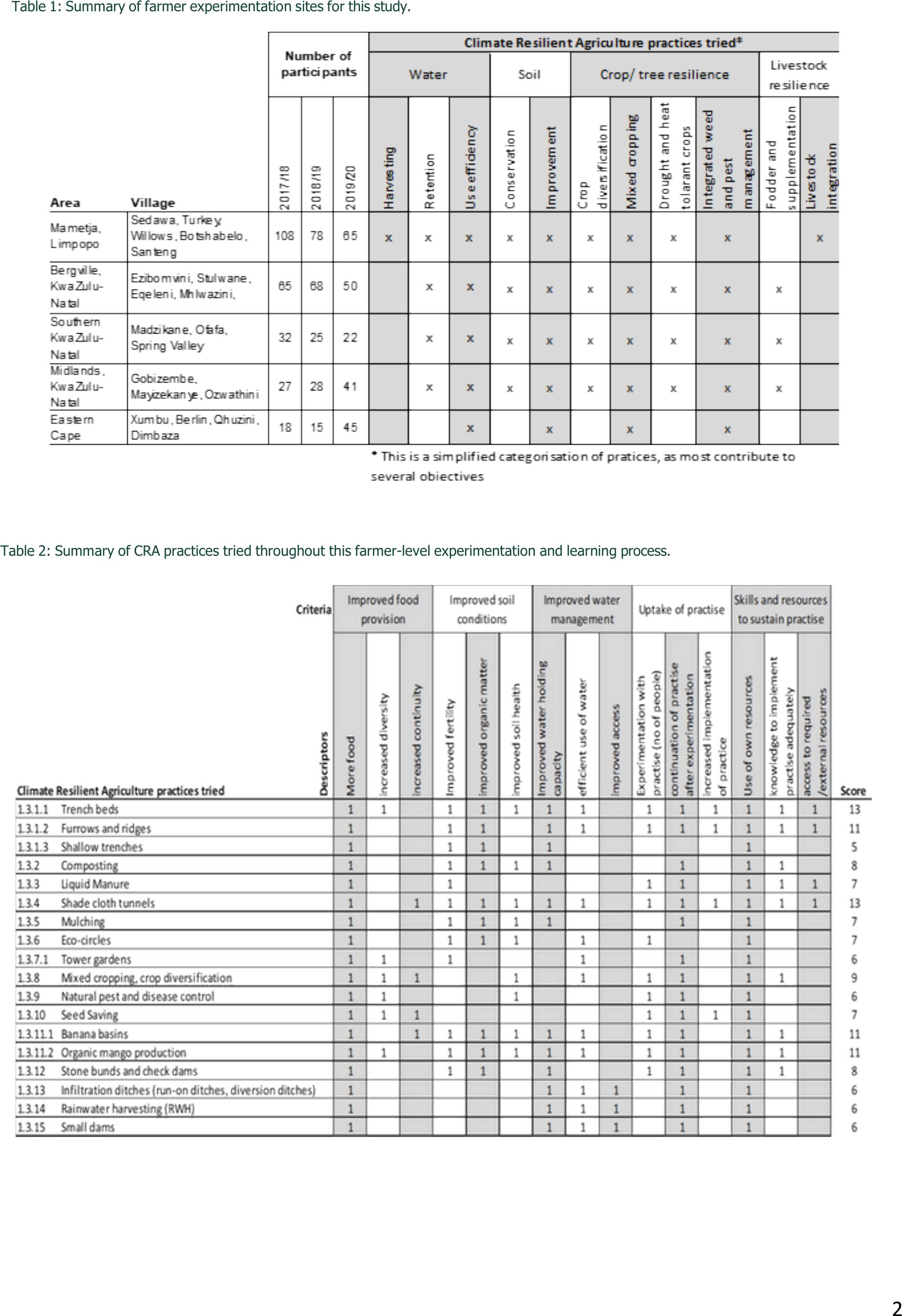

Nearly 100 stakeholders have been involved to date, with around60 organizations/groups/

communities representedrepresentingpolicy and government, operators, financial actors,

interest and influential groups and users.

Figure 2: A diagram representing the types of organisations represented in the uThukela water source partnership.

The adaptive planning process has thus considered present issues and concerns, values and a

vision for the partnership. A vision has been developed: Integration of different entities to

conserve and utilize the landscape and its water, other natural and cultural resources fairly as

well as empower its people, to build resilience and achieve sustainable socio-economic

growth.

Activitiesthat have been proposed, which will now be further explored and developed into an

action plan can be summarized as:

ØNetworking coordination and communication

ØEnabling collaborative and aligned action between stakeholders for securing the SWSA

ØFocus on water access, infrastructure and management in the catchment focusing on

the rural poor

ØCoordinate relevant research and monitoring, including data exchange

ØFoster co-learning and co-creation

ØHelp coordinate investment and priority management interventions

ØCreate job opportunities and add more projects and

USERS

!"#$%&'

#()*+,-.

/0(1,23#4)2,52

/6*-)2+57

/655$8%+(52

9*("#$%&'

)*#()*+,-.

/:);2$2+,*#,4<%51,52

/=)5%&4#(11)*$3,2

/>?,4,*@$5(*1,*+

POLICY AND

GOVERNMENT

A%3(*%&

B(@,5*1,*+

C5(@$#$%&

B(@,5*1,*+

0$2+5$#+

D)*$#$E%&$+7

F(#%&

D)*$#$E%&$+7

G%+#?1,*+

D%*%8,1,*+

H8,*#$,2

'I(5%

J%+,542,5 @$ #,2

$*23+)3(*2

OPERATORS

INTEREST AND

INFLUENTIAL

GROUPS

G$@$&42(#$,+7

>5%-,4 9* $ (*2

AB!2'AC!2

D,-$%

:#$,*#,4%*-

H#%-,1$%

FINANCIAL

ACTORS

0(*(52'

I)*-,52

I$*%*#$%&

$*23+)3(*2

G(11)*$+7

85()E2

K)2$*,22,2

'4C5$@%+,

2,#+(5

>()5 $2 1 '

L(2E$+%&$+7

2,#+(5

=,2()5#,

)2,52

%22(#$%3(*2

F(#%&

G(*2,5@%3(*

'45,2+(5%3(*

85()E2

-water resources:governance and management

-land, landscapes, the environment

-people: society and communiJes

WATER, LAND AND PEOPLE

>5%-$3(*%&

H)+?(5$3,2

=,&$8$()2

':E$5$+)%&

85()E2

C(M,542,5@$#,2

$*23+)3(*2

6*<5%2+5)#+)5,

$*23+)3(*2

A%+)5,

G(*2,5@%3(*

$*23+)3(*2

J%5-

#(11$N,,2

%*-

#()*#$&&(52

J%+,5

G(11$N,,2

INTHE UPPERuTHUKELA CATCHMENT

24

ØContinue the gains from related projects linking with the various programmes of work in

the catchment for added effort.

The vision and high-level activities for this MSP align well with the sister platforms for the

Mpumalanga and Eastern Cape Drakensberg SWSAs.A recent evaluation of the uMzimvubu

Catchment Partnership programme provides further insight into best practice in

implementation.

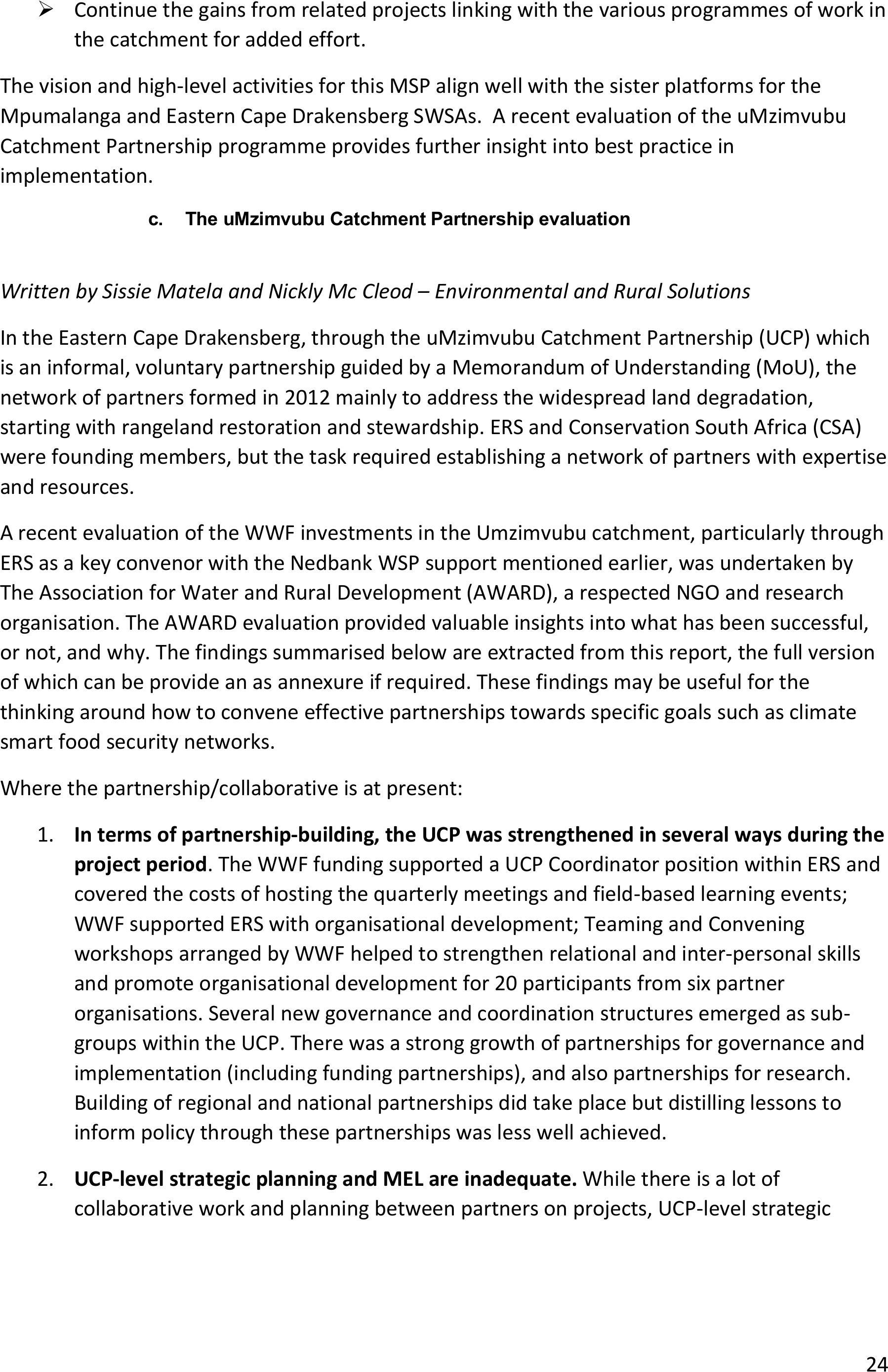

c.The uMzimvubu CatchmentPartnershipevaluation

Written by Sissie Matela and Nickly Mc Cleod – Environmental and Rural Solutions

In the Eastern Cape Drakensberg, through the uMzimvubu Catchment Partnership(UCP) which

is an informal, voluntary partnership guided by a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), the

network of partners formed in 2012 mainly to address the widespread land degradation,

starting with rangeland restoration and stewardship. ERS and Conservation South Africa (CSA)

were founding members,but the task required establishing a network of partners with expertise

and resources.

A recent evaluation of the WWF investments in the Umzimvubu catchment, particularly through

ERS as a key convenor with the Nedbank WSP support mentioned earlier, was undertaken by

The Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD), a respected NGO andresearch

organisation. The AWARD evaluation provided valuable insights into what has been successful,

or not, and why. The findings summarised below are extracted from this report, the full version

of which can be provide an as annexure if required. Thesefindings may be useful for the

thinking around how to convene effective partnerships towards specific goals such as climate

smart food security networks.

Where the partnership/collaborative is at present:

1.In terms of partnership-building, the UCP was strengthened in several ways during the

project period. The WWF funding supported a UCP Coordinator position within ERS and

covered the costs of hosting the quarterly meetings and field-based learningevents;

WWF supported ERS with organisational development;Teaming and Convening

workshops arranged by WWF helped to strengthen relational and inter-personal skills

and promote organisational development for 20 participants from six partner

organisations. Several new governance and coordination structures emergedas sub-

groups within the UCP. There was a strong growth of partnerships for governance and

implementation (including funding partnerships), and also partnerships for research.

Building of regional and national partnerships did take place butdistilling lessons to

inform policy through these partnerships was less well achieved.

2.UCP-level strategic planning and MEL are inadequate.While there is a lot of

collaborative work and planning between partners on projects, UCP-level strategic

25

planning is a rather adhocprocess. The UCP’s theory of change is not well developed; it

is not detailed enough to be useful and doesn’t identify assumptions or link to research

questions. While the UCP strategy document is useful, the practiceof strategizing needs

to be strengthened. There is a need for more reflective practice, both within each

organisation and collectively in the UCP. Although attempts have been made to improve

M&E processes and tools, these efforts have had a rather stop-start character. The M&E

function has been very under-resourced over the years.

3.Landscape and livelihoods-related outcomes were well achieved. Landscape outcomes

included improved rangeland condition and ground cover to prevent erosion and

provide good grazing for cattle, removal of alien invasive tree species and improved

water quality through protection of springs from surface contamination. In terms of

livelihoods, outcomes included skills development and employment opportunities for

youth (a particular focus of the First Rand project), employment through clearing of

wattle, and support for entrepreneurship linked to the development of green business

value chains for livestock and charcoal production. However, wattle regrowth is a major

threat to the investments already made and a solution is needed to deal with this.

4.Teaming and Convening workshopsarranged by WWF helped to strengthen relational

and inter-personal skills and promote organisational development for 20 participants

from six partner organisations (ERS, CSA, MLM, EWT, Lima and WWF). This included

helping administrative and financial staff to understand the needs and priorities of

‘implementation’ staff and vice versa.

5.Several new governance and coordination structuresemerged as sub-groups within the

UCP. These mostly developed organically to meet the needs of collaborative projects

(some being funded through WWF), but also partly in response to a push by SANBI to

establish “communities of practice” or working groups focused on particular topics.

They are important because they show that partners recognise the need to work

together, and they help to guide and document these collaborations, for example

through promoting regular meetings and the keeping of minutes or meeting notes.

oThe Water and Alien Vegetation Task Force or WATF(involving ERS, local

implementers, DFFE, SANBI and research organisations).

oThe Matatiele Resource Management Unit(ERS, Avocado Vision and

Inhlabathi).

oThe Water Security Project Steering Committee(all six Traditional Authorities,

ERS, Lima, CSA, Department of Water & Sanitation, CONTRALESA, Matatiele LM

and the Alfred Nzo District Municipality as the Water Services Authority).

oA Waste Managementgroup led by Matatiele LM and supported by ERS, CSA

and Lima.

26

oA Carbon Possibilities and Ecosystem-Based Adaptationgroup led by CSA.

oA Researchtask team is being discussed to guide the growing body of research

work in the catchment.

oThe local Grazing Associationsformed through the work with livestock farmers

are extremely important local governance institutions that have cemented

partnerships between farmers, the Traditional Authorities, and the NGOs

involved (CSA, ERS, Lima, Meat Naturally).

•The UCP shifted overthe time period of the evaluation from a somewhat “competitive”

space between the various partners – especially the NGOs - to a more collaborative

spacewhere joint implementation of projects has become more frequent

1

. Reasons

suggested for this shift include an increasingly deliberate focus on social learning,

through the influence of SANBI and the Living Catchments Project, as well as

strengthening of interpersonal relationships through formal and informal interactions

over time.

2

•The fact that local government partners as well as Traditional Authorities have been

drawn in and become key playersin the partnership is unusual compared to most other

places around the country

3

. This is beneficial because the traditional leaders are

important role playersin natural resource governance and land allocation in communal

areas, and they are in a good position to identify ecological and social priorities in their

communities. The establishment of the Maloti Thaba Tsa Metsi Protected Area (see

Section 3.1.2) would never have been possible without the strong support and

involvement of the six Traditional Authorities, for example. The local and district

municipalities, on the other hand, are important for embedding the work within formal

planning processes (e.g.,Integrated Development Plans, Spatial Development

Frameworks and Local Economic Development Plans). Although this does not

necessarily guarantee funding support, it does help to promote a unified vision of what

is needed in the area.

The following mechanismswere identified as enabling progresstowards outcomes:

•The characteristics of the core UCP partners (ERS, Lima, CSA) make the UCP effective in

achieving outcomes in the catchment. These are the key organisations that do the work

on the ground. Characteristics included relational warmth, shared values and a shared

way of working described as respectful, participatory, transparent and culturally

appropriate. The “peripheral partners” are important in supporting the core, providing

1

Snorek et al., in press; Interview17-govt

2

Interview12-NGO

3

Interview17-govt, Interview26-NGO, Interview7-TA

27

resources, expanding the scope, transferring ideas and lessons to other areas, sharing

different ways of addressing problems, conducting research, and linking to policy.

•The co-implementation of projects (enabled by the shared values and long-standing

relationships within the UCP) produced a lot of learning for the implementing

organisations and led to both innovation and collaborative refining of models that work.

•Learning and sharing of successes within the UCP community led to members applying

models elsewhere (outside the uMzimvubu catchment).

•Creativity and flexibility among the core NGO partners wereinstrumental in building a

group of young people who could effectively support projects and act as ambassadors at

community level. This reaped huge benefits and produced a multiplier effect for most

aspects of work.

•The diversity of organisations in the UCP (NGO, different levels of government,

parastatals, social enterprises, Traditional Authorities,and research organisations)

enables meaningful division of labour between partners.

The following mechanisms acted as constraints to progress:

•ERS’ capacity and functioning. Given its key role in the UCP, the functioning of ERS

affects the functioning of the UCP. The main issues identified were busyness and “taking

on too much”; persistent underfunding of operational overheads; the absence of any

M&E personnel to assist with reporting, reflection and learning, and knowledge

management; and difficulty attracting qualified and experienced staff in a remote

geographical location. A red flag is the fact that both of ERS’ directors are looking to

retire in the next few years, and no succession plan is yet in place.

•Budget and staffing constraints within municipalities, as well as a lack of political will in

some cases, mean that local government does not play as much of a role in the UCP’s

strategic planning and M&E as it should.

•The COVID-19 pandemic affected the extent to which some of the outcomes could be

achieved (e.g.,hectares cleared, youth entrepreneurs supported).

The evaluation recommends that the UCP should continue to be nurtured as a community of

practice and innovation system, and that the group of youth “Eco-champs” should be

expanded,and the role made less precarious.

Below, a summary of stakeholder engagement and participatory tools developed and used

within both the UCP and its ‘anchor project’ extension - the Maloti Thaba Tsa Metsi (MTTM), a

proposed protected area along the upper Umzimvubu watershed.

Some of the important components identified, which became an integral part of the values

pack, include:

28

•Deepening the relationship with local leadership and communitiesby establishing and

growing an interactive, relational, trustworthy local presence of NGOs throughoutthe

upper Umzimvubu Catchment. This required co-creation of implementation projects

together with all stakeholders, and timesous cost-effective delivery of outcomes,

including spring protection, youth employment job creation, beef value chains, alien

plant clearing etc

•Improving coordination between research institutionsand local role players through

sharing of results to ensure benefits accrue for growth and development. This required

crafting a research priorities ‘wishlist’ and ensuring that academic institutions align with

catchment needs andshare findings back with participants. A knowledge hub and

monitoring and learning framework are beginning to emerge and need much more

attention to become effective.

•Sharing lessonsbetween catchments by documenting projects, lessons learned,

reflections and sharing these between catchments

•Deepen and expand the active community of practice around EI nationally, through

catchment-basedindabas and interactive field-based learning exchanges to foster

effective transformative social learning

•Fostering participatory Citizen science practises as a basis for monitoring, evaluation

and learning:action-orientedawareness building where community members confront

the consequences of specific actions and are an integral part of designing solutions. The

approach is easily adapted based on observations and encourages deeper interest in

real research for better practise and outcomes. The pictures below show field-based

citizen science activities where village residents, youth and ERS field co-ordinators link

with research institutions to apply rigorous science in a well-designedand easily applied

citizen science format.

•Participation in IDP Forumsto gather information on what the priority developmental

issues are that come directly from communities: the process follows along provisions of

Section 25 of the Municipal Systems Act (MSA) no.32 of 2000. ERS shares information on

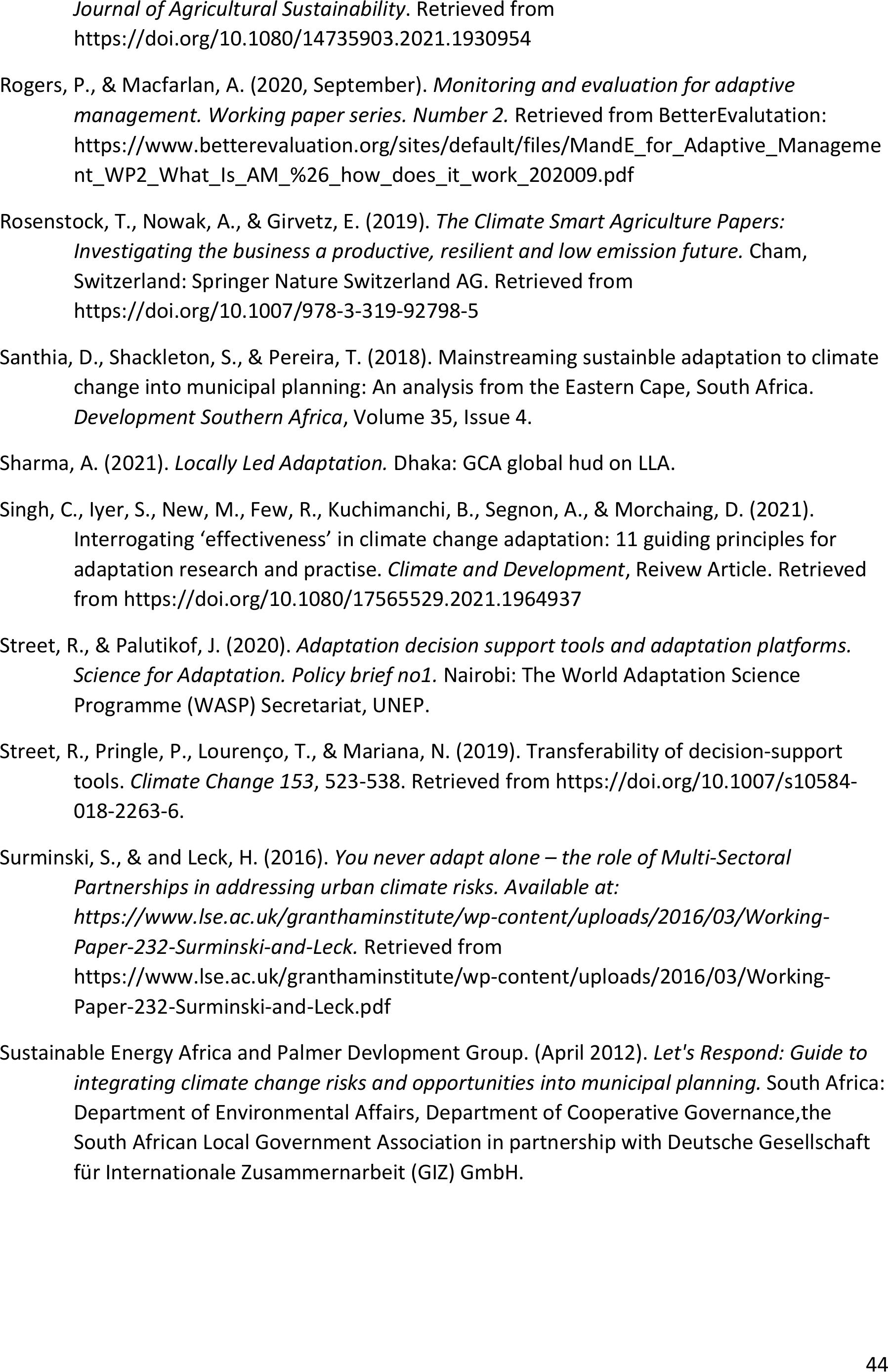

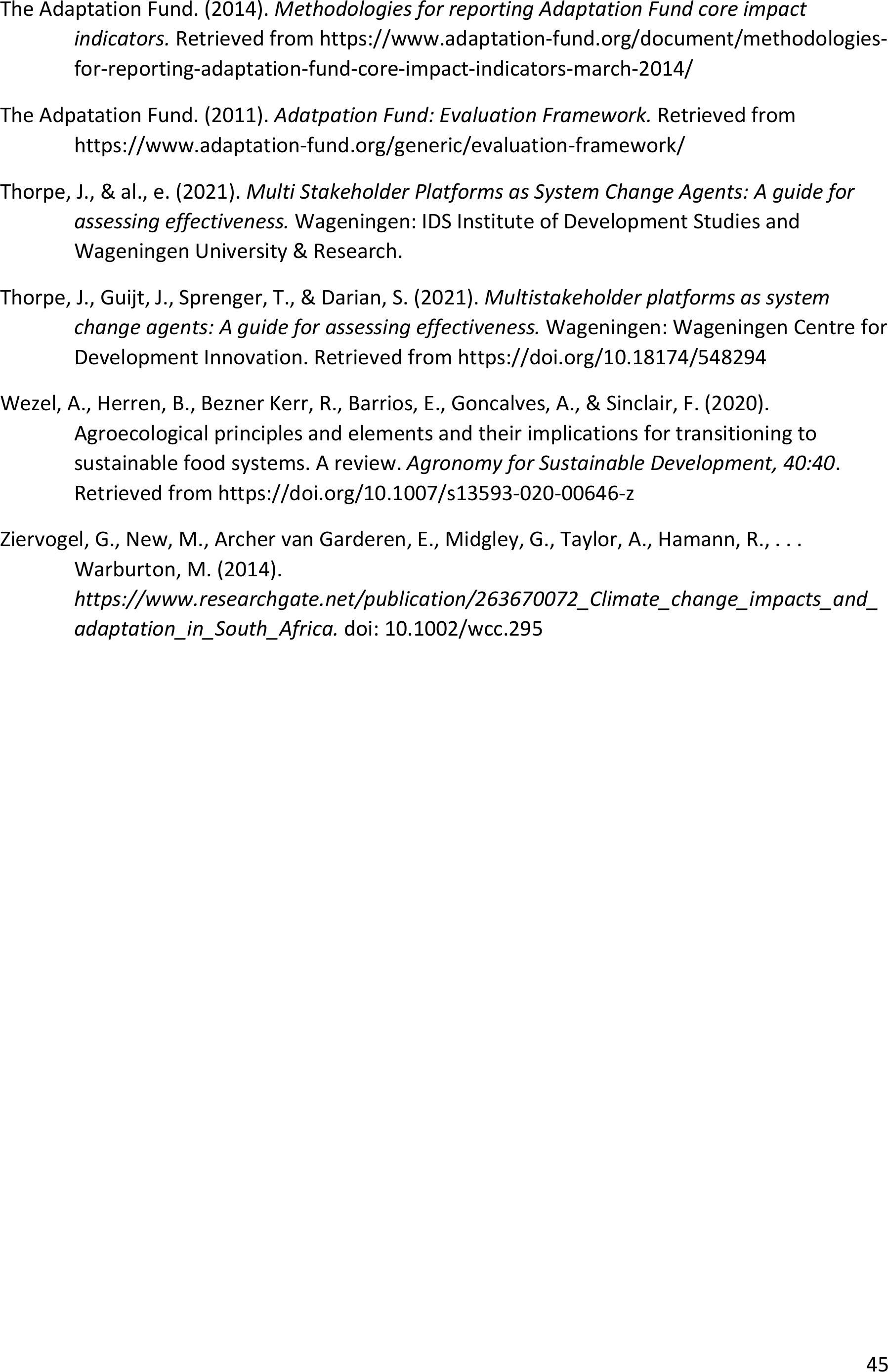

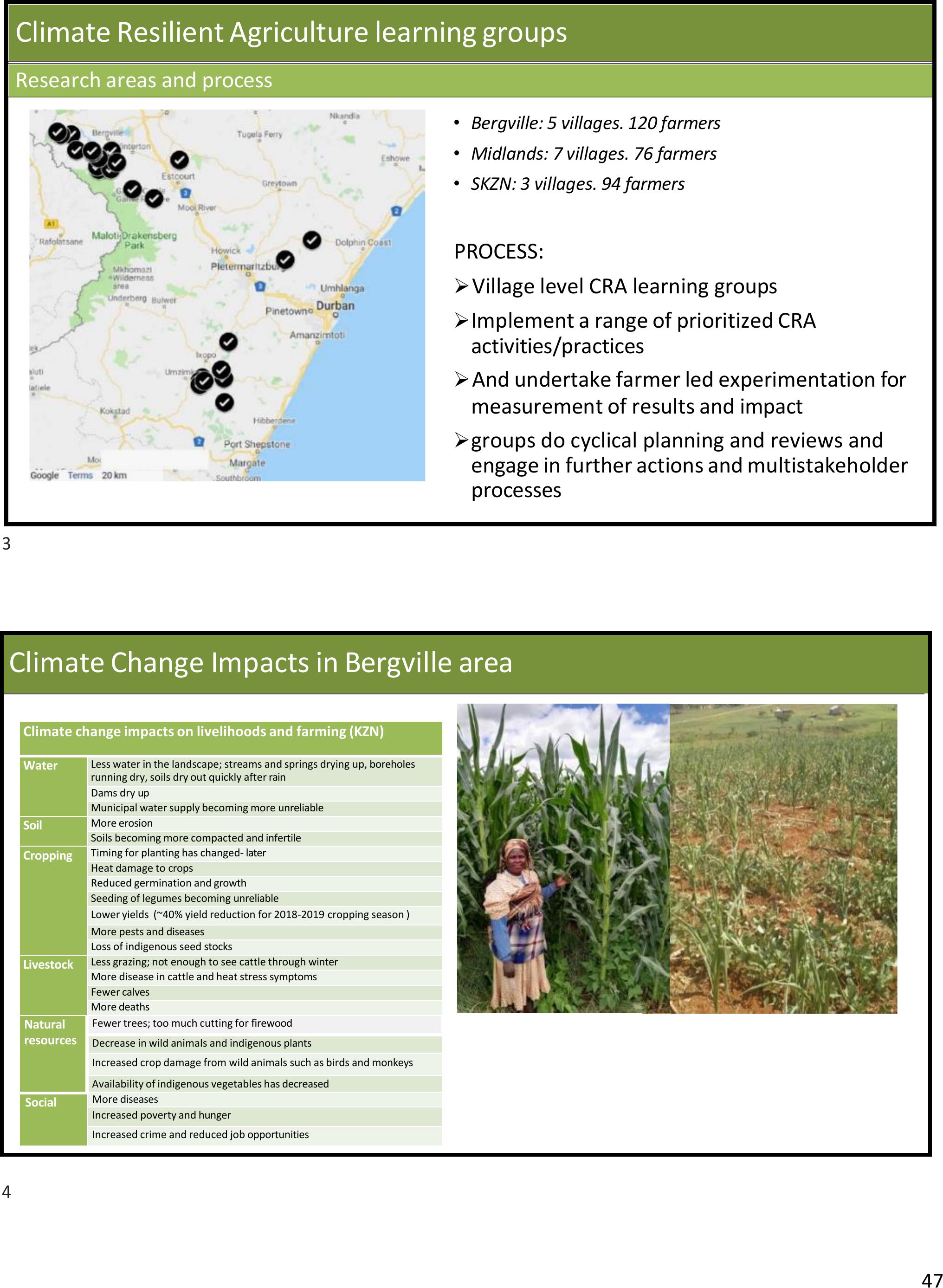

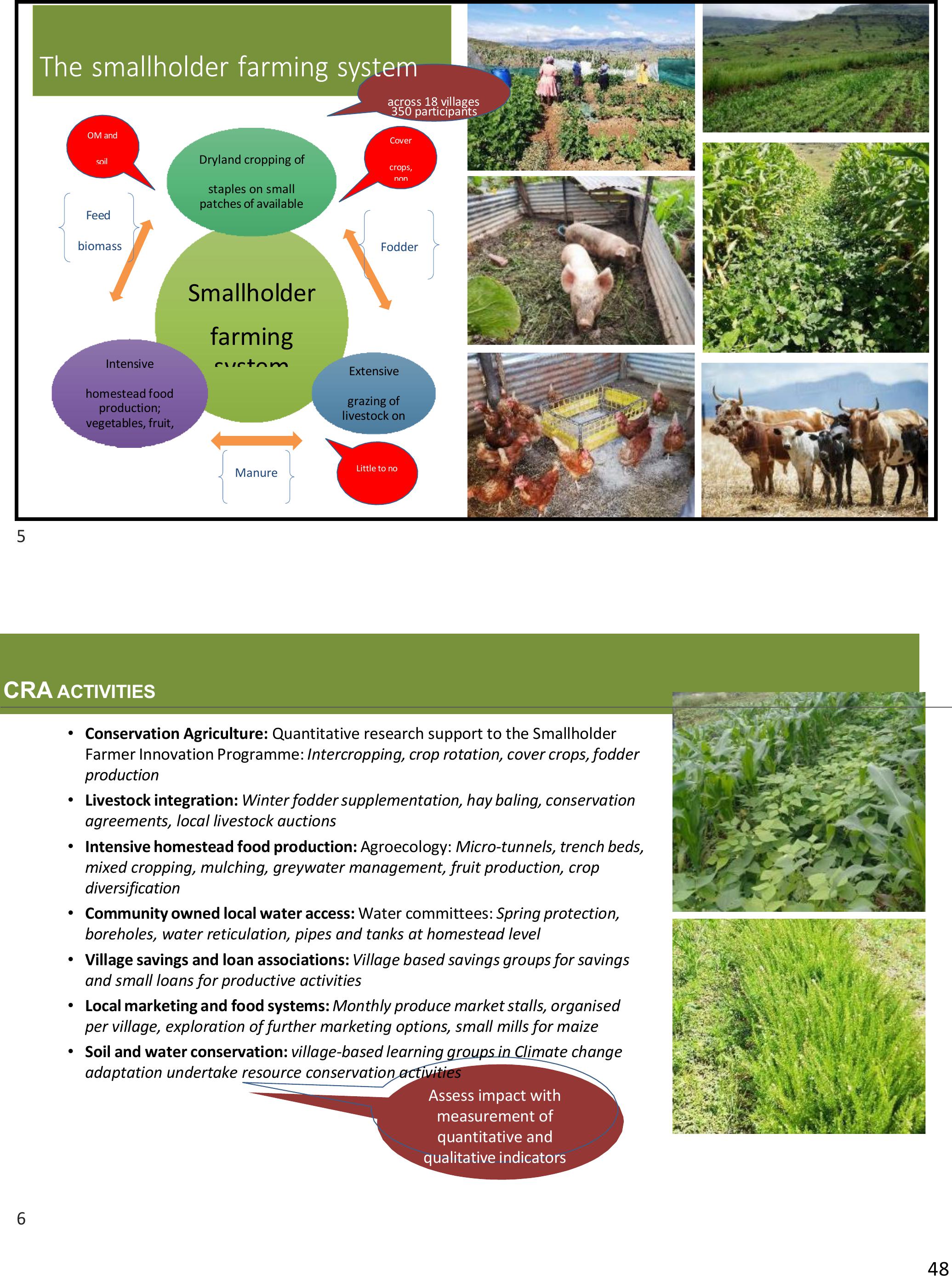

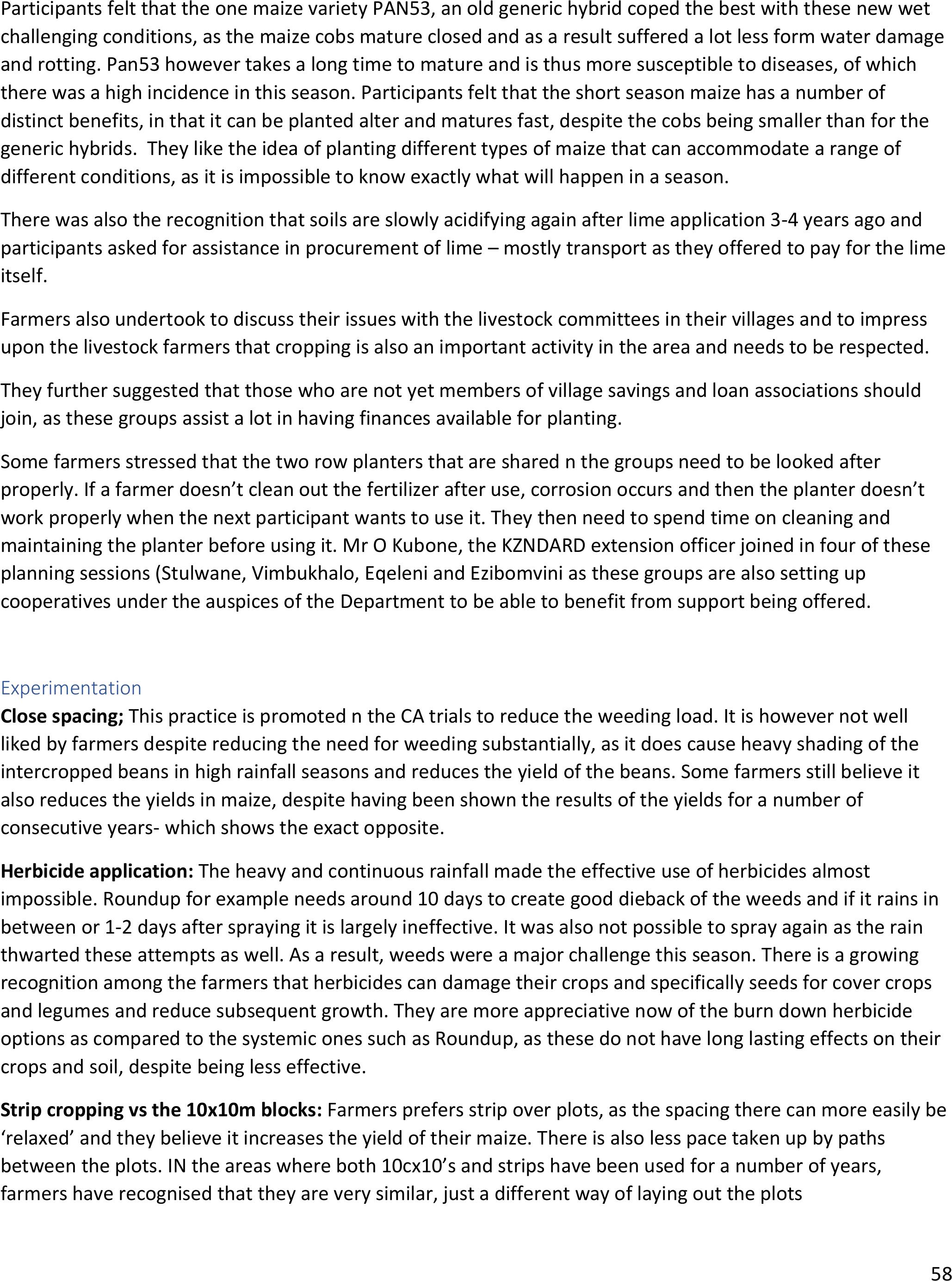

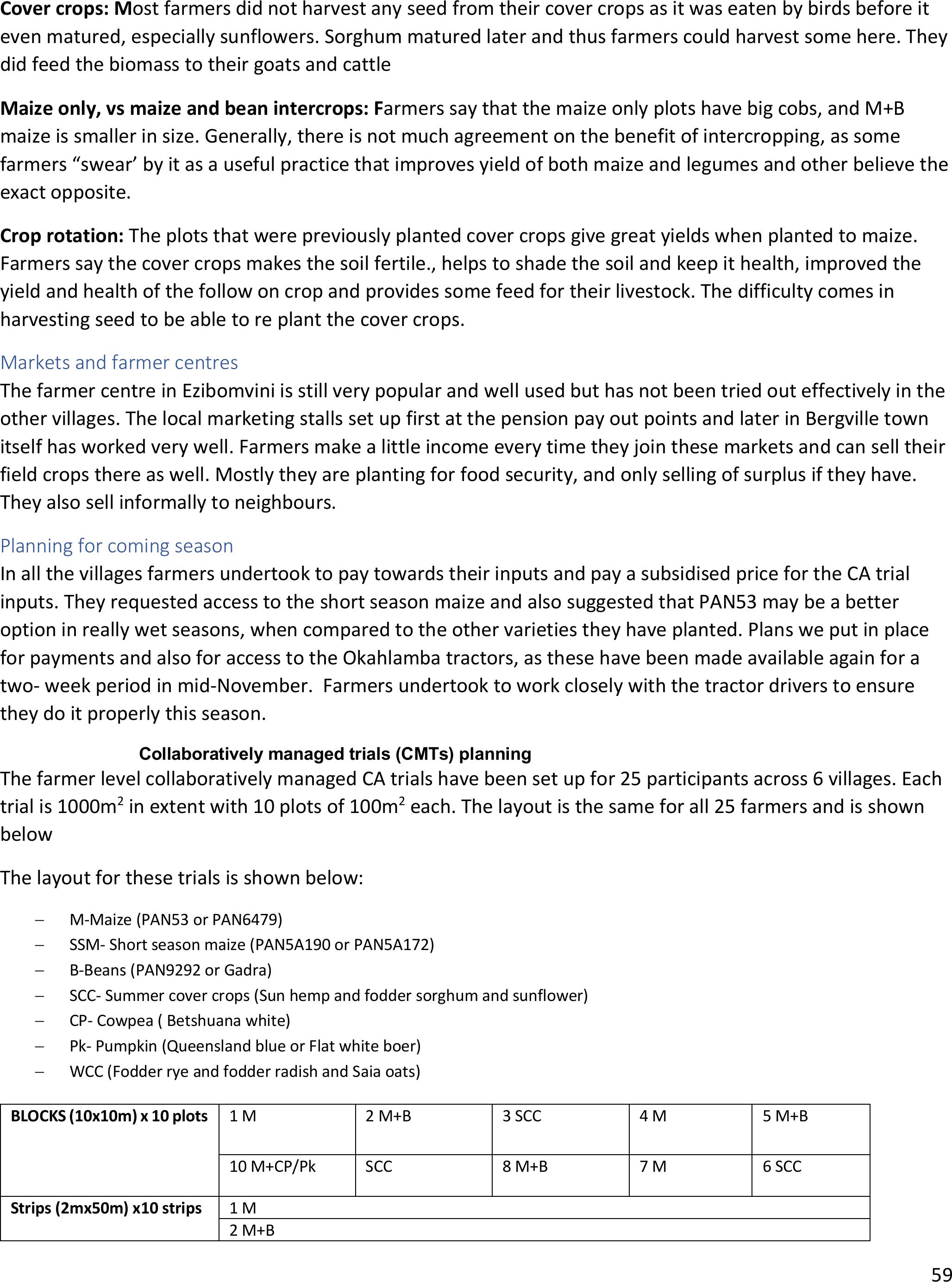

specific projects and associated budgets, specifically under public education and