A smallholder farmer level decision support system

for climate resilient farming practices improves

community level resilience to climate change. No2:

Impact of climate resilient practices on rural

livelihoods

Submitted by Erna Kruger (Director MahlathiniDevelopment Foundation - MDF)

Ph: 0828732289, Email: info@mahlathini.orgWeb: www.mahlathini.org

Partners: Erna Kruger, Mazwi Dlamini, Samukelisiwe Mkhize, Temakholo Mathebula, Phumzile

Ngcobo, Betty Maimela, Sylvester Selala and Lulama Magenuka (MDF)

Palesa Motaung, Nonkanyiso Zondi, Sandile Madlala, Khetiwe Mthethwa, Andries Maponya,

Nozipho Zwane, Lungelo Buthelezi, and Zoli Gwala (students and interns)

Mr Lawrence Sisitka (Research Associate- Environmental Learning Research Centre- Rhodes

University)

Mr Nqe Dlamini (StratAct)

Mr Chris Stimie (Rural Integrated Engineering)

Mr Jon Mc Cosh, Ms Brigid Letty (Institute of Natural Resources)

Mr Hendrik Smith (CA coordinator for GrainSA)

Ms Sharon Pollard (AWARD)

Ms Lindelwa Ndaba (Lima RDF)

Ms Catherine van den Hoof (formerly of WITS Climate Facility, now the United Nations World

Food Programme)

Introduction

A current Water Research Commission adaptive research process entitled “Collaborative knowledge creation

and mediation strategies for the dissemination of Water and Soil Conservation practices and Climate Smart

Agriculture in smallholder farming systems”is exploring best practice options for climate resilient agriculture

for smallholders and evaluating the impact of implementation of a range of these practices on the resilience of

agriculture based livelihoods. Alongside this, a decision support methodology and system has been designed to

assist smallholders and the facilitators who support them to make informed and appropriate decisions about

choices of a ‘basket of options’ for implementation at a local level.

The research process is broadly divided into three elements for purposes of clarity, although all three elements

are tackled concurrently:

1. Community climate change adaptation process design

2. Climate resilient agricultural practices and

3. A decision support system.

In this article we focus on the CRA practices and the impact of implementation of these practices on rural

livelihoods.

Climate resilient agriculture (CRA) practices for smallholders

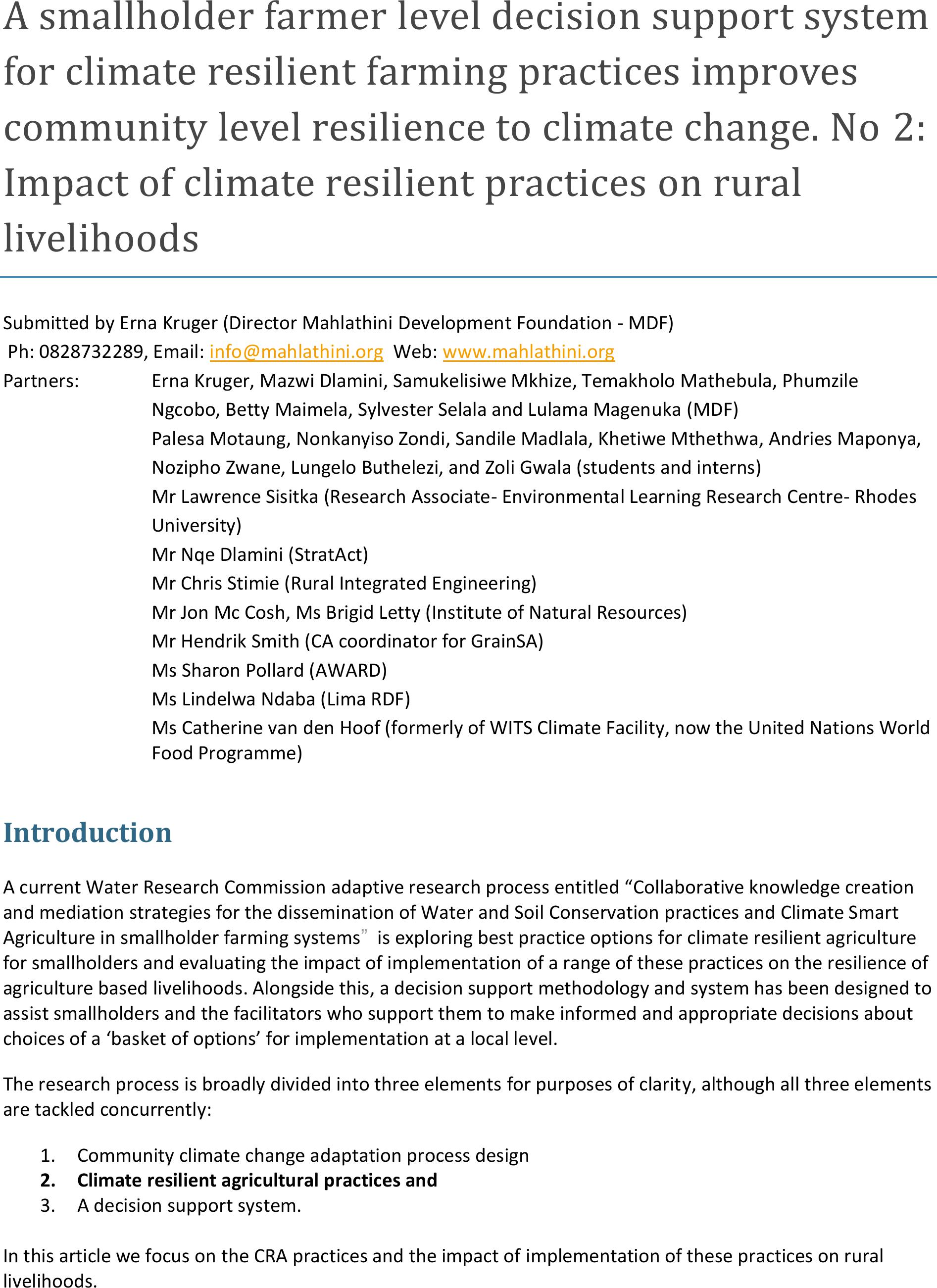

The approach is to work directly with smallholders in local contexts to improve practices and synergise across

sectors. The emphasis is thus at farm/household level. Here CRA aims to improve aspects of crop production,

livestock and pasture management, natural resource management, as well as soil and water management as

depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Household level implementation of CSA integrates across sectors (adapted from Arslan, 2014)

A database of 66 different practices falling into the categories mentioned inthe figure above has been

compiled, based on local suggestions and best bet options from experience and literature.

A selection of the practices is shown in the table below. Farmers decide on practices to try out and implement

depending on their own situations and preferences as well as suggestions made by the facilitation team.

Table 1: a summary of a selection of CRA practices considered and implemented by smallholder farmers

Gardening

Field cropping (Conservation

Agriculture)

Livestock management

Intensive gardening techniques:

including trench beds, mulching, liquid

manure, mixed cropping, planting of

nutritional herbs and multifunctional

plants, fruit production, seed saving

Diversification of cropping:

including legumes and cover

crops (sunflower, millet, sunn

hemp, black oats, fodder rye

and fodder radish)

Fodder production and

management for livestock

Soil and water conservation techniques:

including swales, furrows and ridges,

stone bunds, check dams

Intercropping and crop

rotation; strip cropping options

and spacing

Local feed production

options

Tunnels; Shade cloth structures for

microclimate control

No till planters

Chicken tractors

Rainwater harvesting; in field methods

and storage options, small dams

Mulching, manure and organic

options

Winter supplementation

SYNERGIES

Soil

and water

conservation

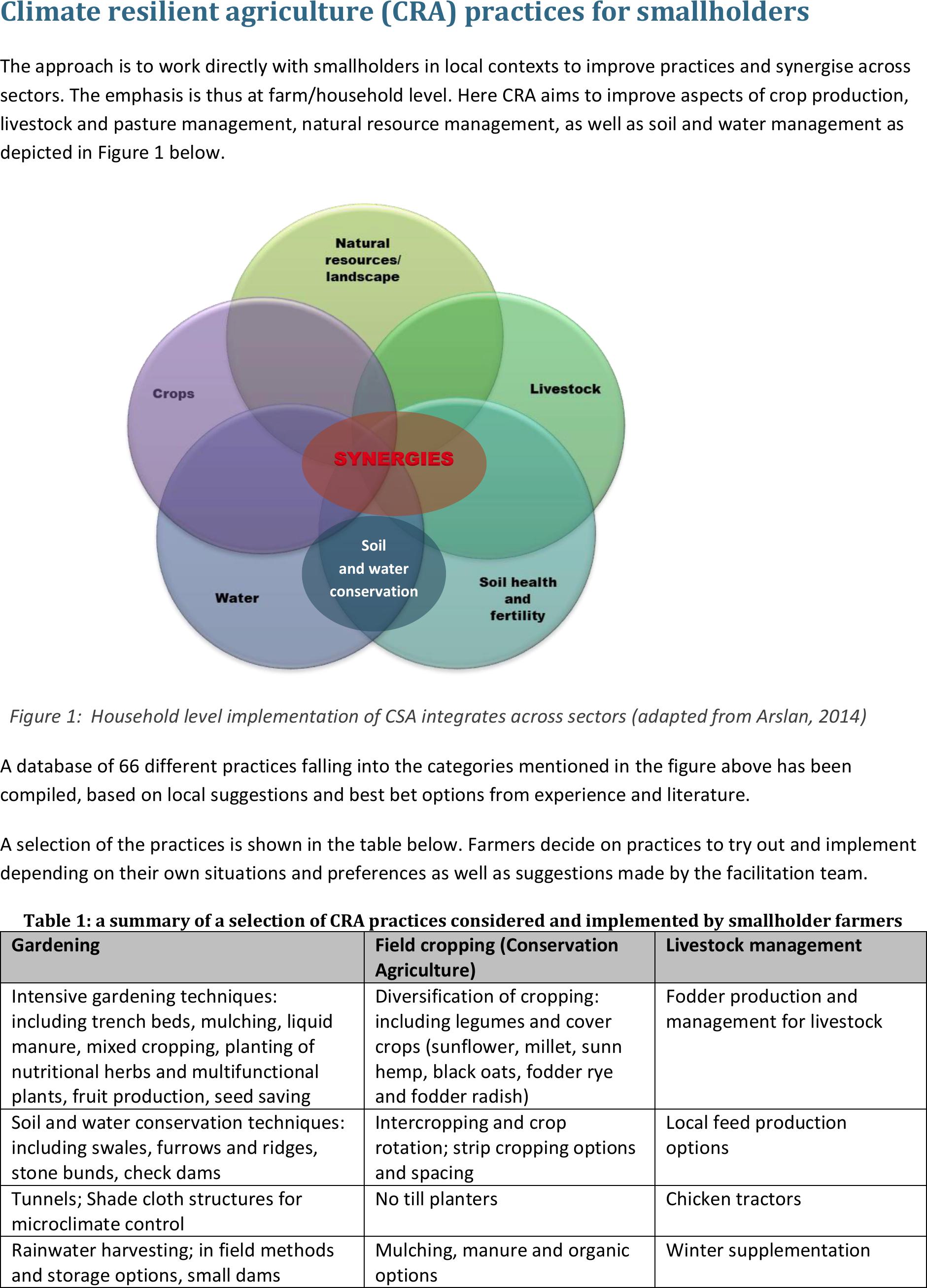

For each practice, a 1-page summary has been put together, that can be presented to smallholders in the

climate change adaptation workshops, for consideration by the smallholder farmers as a new idea or

innovation to experiment with. Below are three illustrative examples

This database provides a resource to farmers and facilitators to choose appropriate climate resilient

agricultural practices for their area and their particular situation. It is one of the input parameters for the

decision support process.

In addition,qualitative and quantitative indicators have been explored to physically assess the impact of these

practices. These have included for example run-off, infiltration, water holding capacity in the soil profile, and

water productivity as well as a number of soil- based parameters such as organic matter content, soil fertility

and microbial activity.

As an example, a farmer level experimentation process consisting of production in trench beds, inside and

outside of shade cloth tunnels was conducted. The control for this experiment was the farmer’s ‘normal’

gardening practice –in this case raised beds.

Above left to right: Spinach grown in a trench bed inside a tunnel, in a trench bed outsidea tunnel and in a

control bed (raised bed), by Phumelele Hlongwane

Farmers kept careful records of the amount of water applied (irrigation) and their harvests (yields), alongside

the research team who worked with local weather stations and soil moisture measurements to assess the

water productivity of these practices.

The table below outlines the resultant water productivity calculation for this experiment. Both conventional

WP calculations and a simpler format suggested by farmers that only uses their water applied were used.

Table 2: Water productivity for production of spinach inside and outside shade cloth tunnels for 2

smallholder farmers in KNV, Bergville

Bgvl June-Sept 2018

Simple scientific method (ET)

Farmers' method (Water applied)

Name of famer

water use

(m3)

Total weight

(kg)

WP

(kg/m3)

water use

(m3)

Total weight

(kg)

WP

(kg/m3)

Phumelele Hlongwane trench

bed inside tunnel

1,65

21,06

12,76

1,85

21,06

11,38

Phumelele Hlongwane; trench

bed outside tunnel

0,83

5,32

6,45

1,75

5,32

3,04

Ntombakhe Zikode trench bed

inside tunnel

1,65

17,71

10,73

2,37

17,71

7,47

Ntombakhe Zikode; trench bed

outside tunnel

0,50

3,35

6,76

0,53

3,35

6,33

The control plots are not included here, as the two farmers realised quite early in the season that their normal

production methods required too much water and opted to focus only on the trench beds. Water productivity

is 60-100% higher for trench beds inside the tunnels when compared to trench beds outside the tunnel –using

the more scientific approach that also takes into account evapotranspiration and leaching. This is a highly

significant result, indicating the potential of micro-climate control in adaptation.

Water productivity calculate only from yields compared to water applied, shows a larger variation in results for

the two participants. They both applied more water to their trench beds outside their tunnels, than inside;

working on the assumption that the reduced growth for the crops outside the tunnel was due to water stress.

This experimentation process assisted in their learning that plant stress also includes other factors such as

temperature, wind and insect damage.

Participatory Impact Assessments

After a cycle of experimentation with the basket of CRA practices (one season/ 6 months), the process is

reviewed and a participatory impact assessment process is conducted with the learning group members. It is

important for community members themselves to develop the impact indicators/criteria

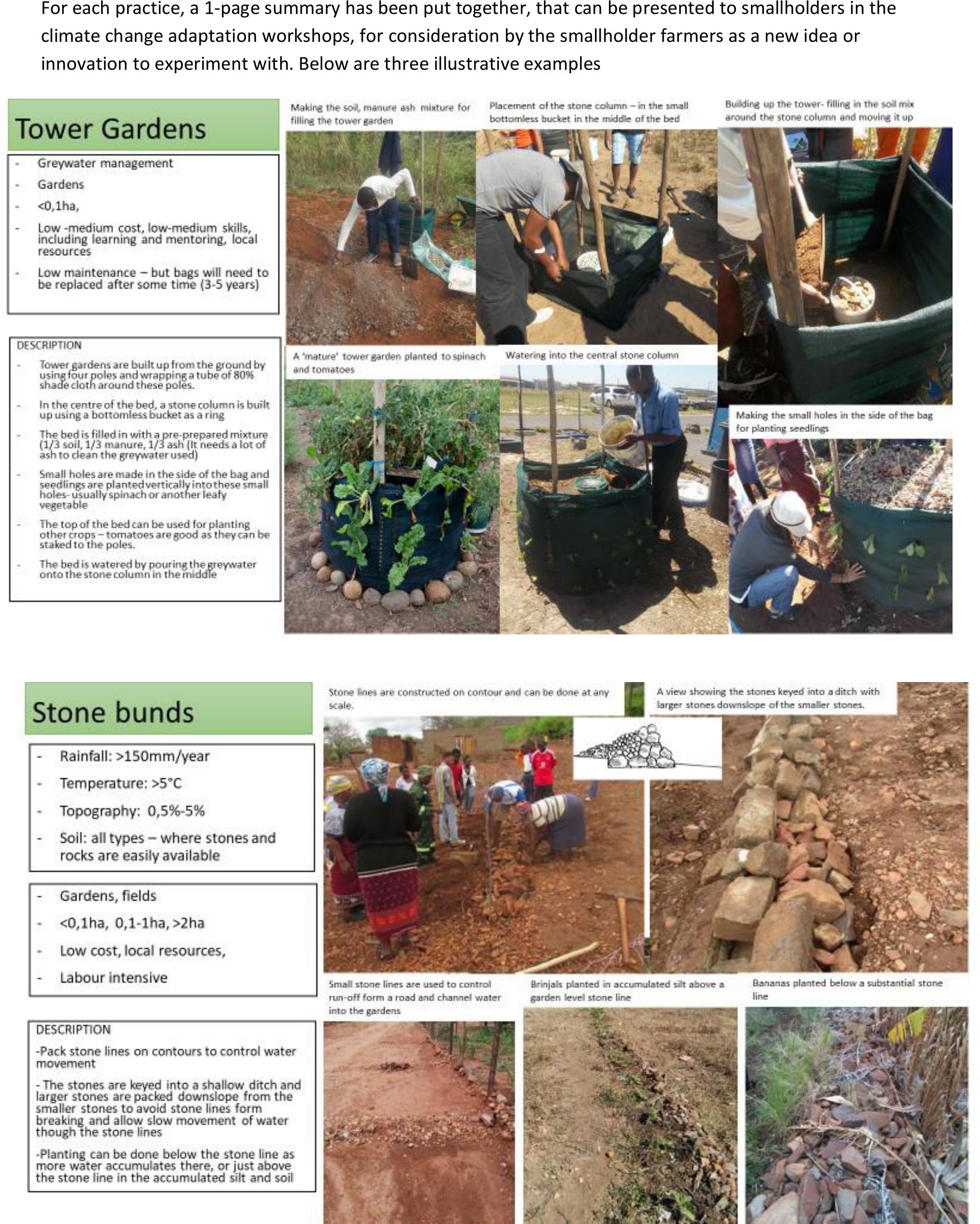

The diagram below provides a summary of all the practices that were tried out for the KZN learning groups for

the 2018-2019 season

1: Tower garden; using greywater for irrigation, planted to kale, spinach and tomatoes

2: Eco-circle with a 2litre bottle (with holes) used for in situ irrigation and planted to a mixture of herbs and

vegetables

3: Bucket drip kits inside a shade cloth tunnel

4: raised bed with mixed cropping planted as a “normal practice control” when comparing with trench beds

5: A Shade cloth tunnel with 3 5x1m trench - beds

6: Inspection of a locally protected spring

7: A shallow trench bed planted to a mixture of green

peppers, chillies and marigolds

8: A deep trench bed planted to a mixture of kale, rape,

mustard spinach and Chinese cabbage

9: A maize and cowpea intercropped conservation

agriculture (CA) plot

10: A CA plot planted to summer cover crops; sunflower,

millet and sunnhemp

11: A CA plot planted to Dolichos beans

12: Making bales of hay with a small manual baler

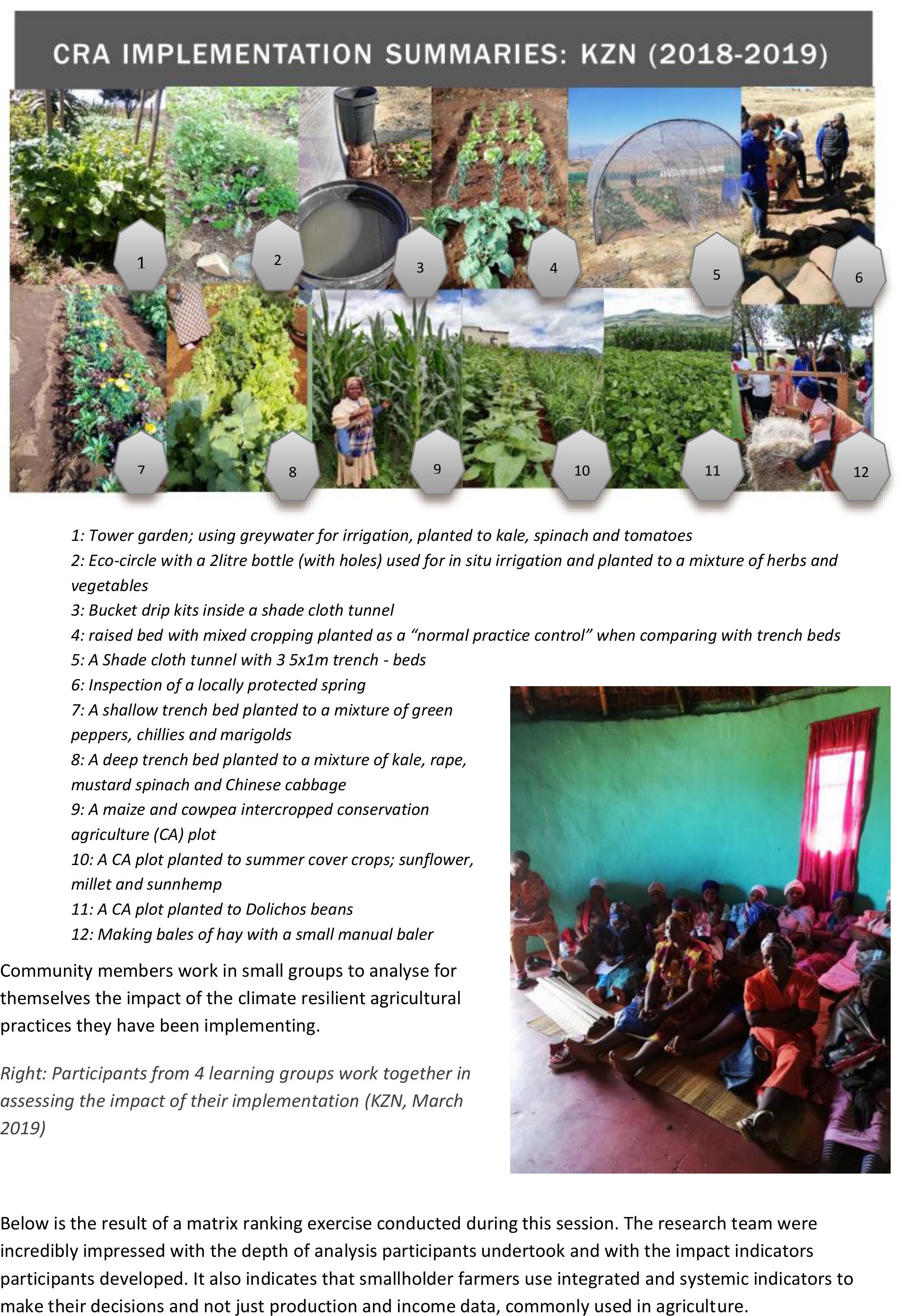

Community members work in small groups to analyse for

themselves the impact of the climate resilient agricultural

practices they have been implementing.

Right: Participants from 4 learning groups work together in

assessing the impact of their implementation(KZN, March

2019)

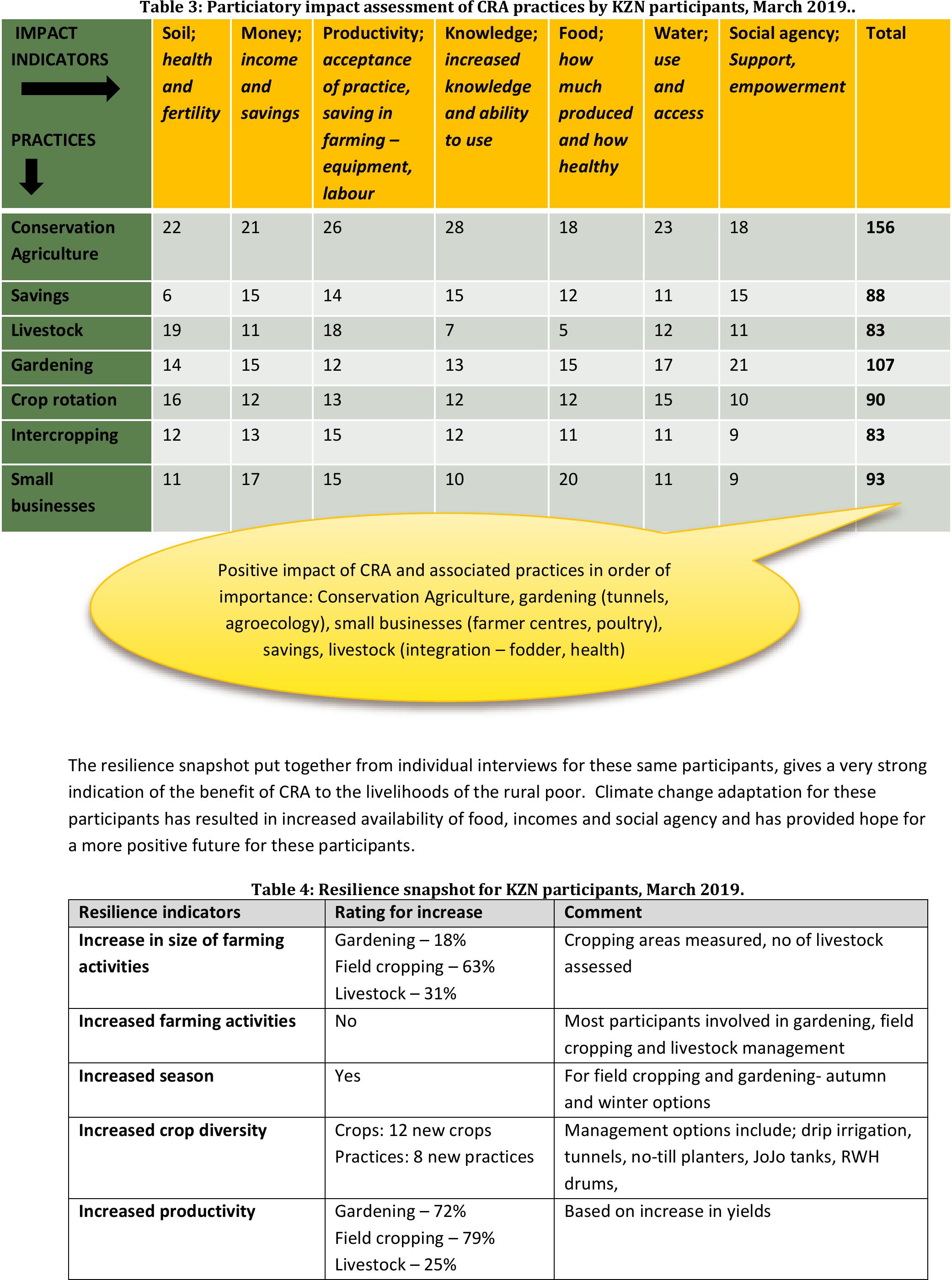

Below is the result of a matrix ranking exercise conducted during this session. The research team were

incredibly impressed with the depth of analysis participants undertook and with the impact indicators

participants developed. It also indicates that smallholder farmers use integrated and systemic indicators to

make their decisions and not just production and income data, commonly used in agriculture.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1

Table 3: Particiatory impact assessment of CRA practices by KZNparticipants, March 2019..

IMPACT

INDICATORS

PRACTICES

Soil;

health

and

fertility

Money;

income

and

savings

Productivity;

acceptance

of practice,

saving in

farming –

equipment,

labour

Knowledge;

increased

knowledge

and ability

to use

Food;

how

much

produced

and how

healthy

Water;

use

and

access

Social agency;

Support,

empowerment

Total

Conservation

Agriculture

22

21

26

28

18

23

18

156

Savings

6

15

14

15

12

11

15

88

Livestock

19

11

18

7

5

12

11

83

Gardening

14

15

12

13

15

17

21

107

Crop rotation

16

12

13

12

12

15

10

90

Intercropping

12

13

15

12

11

11

9

83

Small

businesses

11

17

15

10

20

11

9

93

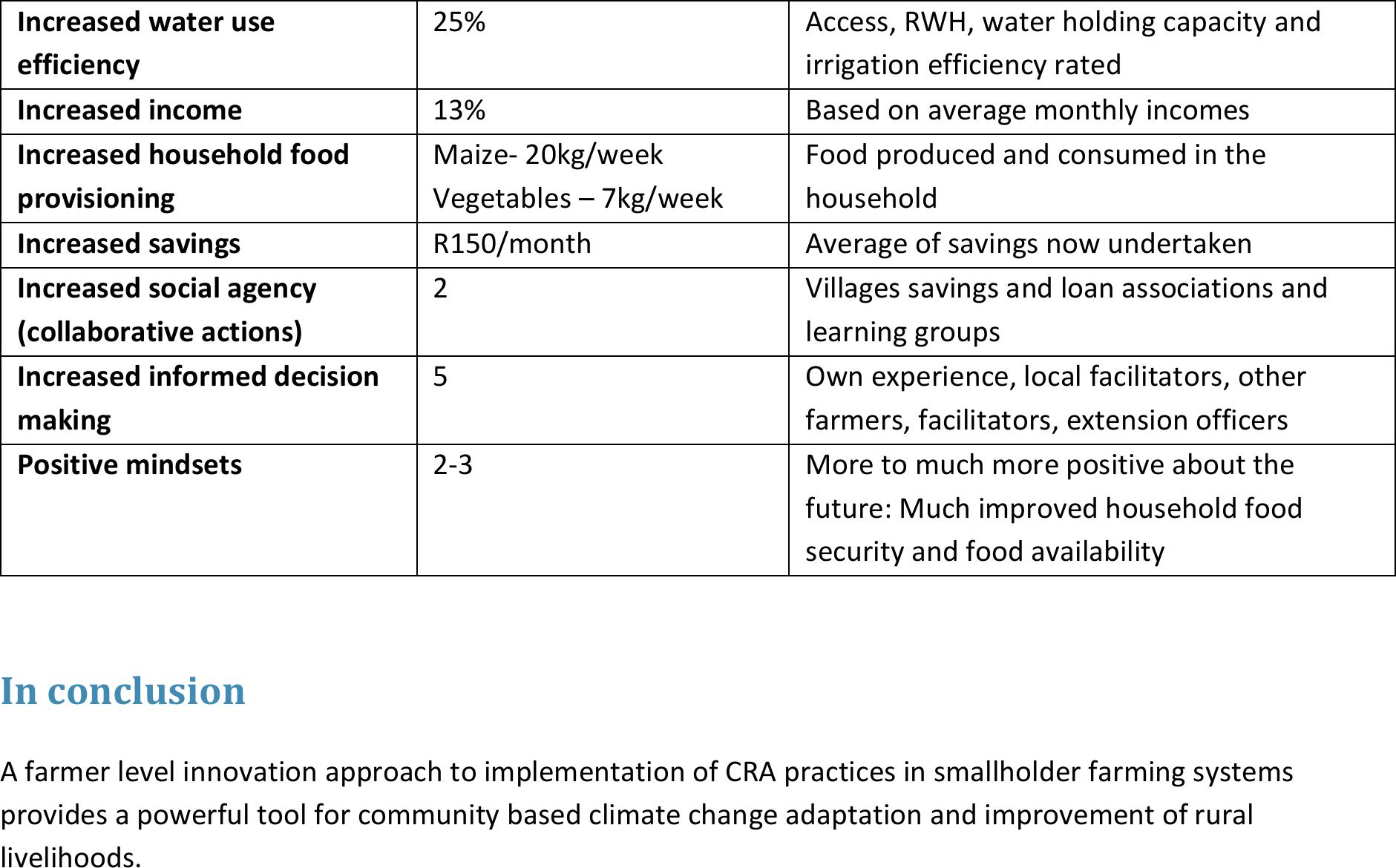

The resilience snapshot put together from individual interviews for these same participants, gives a very strong

indication of the benefit of CRA to the livelihoods of the rural poor. Climate change adaptation for these

participants has resulted in increased availability of food, incomes and social agency and has provided hope for

a more positive future for these participants.

Table 4: Resilience snapshot for KZN participants, March 2019.

Resilience indicators

Rating for increase

Comment

Increase in size of farming

activities

Gardening –18%

Field cropping –63%

Livestock –31%

Cropping areas measured, no of livestock

assessed

Increased farming activities

No

Most participants involved in gardening, field

cropping and livestock management

Increased season

Yes

For field cropping and gardening- autumn

and winter options

Increased crop diversity

Crops: 12 new crops

Practices: 8 new practices

Management options include; drip irrigation,

tunnels, no-till planters, JoJo tanks, RWH

drums,

Increased productivity

Gardening –72%

Field cropping –79%

Livestock –25%

Based on increase in yields

Positive impact of CRA and associated practices in order of

importance: Conservation Agriculture, gardening (tunnels,

agroecology), small businesses (farmer centres, poultry),

savings, livestock (integration –fodder, health)

Increased water use

efficiency

25%

Access, RWH, waterholding capacity and

irrigation efficiency rated

Increased income

13%

Based on average monthly incomes

Increased household food

provisioning

Maize- 20kg/week

Vegetables –7kg/week

Food produced and consumed in the

household

Increased savings

R150/month

Average of savings now undertaken

Increased social agency

(collaborative actions)

2

Villages savings and loan associations and

learning groups

Increased informed decision

making

5

Own experience, local facilitators, other

farmers, facilitators, extension officers

Positive mindsets

2-3

More to much more positive about the

future: Much improved household food

security and food availability

In conclusion

A farmer level innovation approach to implementation of CRA practices in smallholder farming systems

provides a powerful tool for community based climate change adaptation and improvement of rural

livelihoods.