A smallholder farmer level decision support system

for climate resilient farming practices improves

community level resilience to climate change. No1:

Community climate change adaptation process

design

Submitted by Erna Kruger (Director Mahlathini Development Foundation - MDF)

Ph: 0828732289, Email: info@mahlathini.orgWeb: www.mahlathini.org

Partners: Erna Kruger, Mazwi Dlamini, Samukelisiwe Mkhize, Temakholo Mathebula, Phumzile

Ngcobo, Betty Maimela, Sylvester Selala and Lulama Magenuka (MDF)

Palesa Motaung, Nonkanyiso Zondi, Sandile Madlala, Khetiwe Mthethwa, Andries Maponya,

Nozipho Zwane, Lungelo Buthelezi, and Zoli Gwala (students and interns)

Mr Lawrence Sisitka (Research Associate- Environmental Learning Research Centre- Rhodes

University)

Mr Nqe Dlamini (StratAct)

Mr Chris Stimie (Rural Integrated Engineering)

Mr Jon Mc Cosh, Ms Brigid Letty (Institute of Natural Resources)

Mr Hendrik Smith (CA coordinator for GrainSA)

Ms Sharon Pollard (AWARD)

Ms Lindelwa Ndaba (Lima RDF)

Ms Catherine van den Hoof (formerly of WITS Climate Facility, now the United Nations World

Food Programme)

Summary

The more extreme weather patterns with increased heat, decreased precipitation and more extreme rainfall

events; increase of natural hazards such as floods, droughts, hailstorms and high winds thatcharacterise climate

change place additional pressure on smallholder farming systemsand has already led to severelosses in crop

and vegetable production and mortality in livestock.A significant proportion of smallholders haveabandoned

agricultural activities andthis number is still on the increase. Smallholders are generally not well prepared for

these more extreme weather conditions and experience highlevels of increased vulnerability as a consequence.

It is becoming clear thatclimate change will have drastic consequences for low-income and otherwise

disadvantaged communities. Despite their vulnerability, these communities will have to make the most climate

adaptations. It is possible for individual smallholders to manage their agricultural and natural resources better

and in a manner that could substantially reduce their riskand vulnerability generally and more specifically to

climate change. Through a combination of best bet options in agro-ecology, water and soil conservation, water

harvesting, conservation agriculture and rangeland management a measurable impact on livelihoods and

increased productivity can be made.

Processes such as collaborative, participatory research thatincludes scientists and farmers, strengthening of

communication systems for anticipating and responding to climaterisks, and increased flexibility in livelihood

options, which serve to strengthen coping strategies in agriculture for near-term risks from climate variability,

provide potential pathways for strengthening adaptive capacities for climate change.

Mahlathini Development Foundation and our partners and collaborators (Universities, NGOs, CSI initiatives,

District and Local Municipalities and Government Departments), have been working within the socio-

ecological and social learning space to assist smallholder farmers in KZN, Limpopo and the Eastern Cape to

improve their resilience and adaptive capacity to climate change by designing and testing a participatory

smallholder level decision support system for implementing climate resilient agricultural practices.

Within this process smallholder farmers explore and analyse their understanding of climate change and the

impacts of these changes on their livelihoods and agricultural systems. They explore adaptive strategies and

measures (local and external), prioritize appropriate practices for individual and group experimentation and

implementation, assess the impact of these new practices and processes on their livelihoods and re-plan their

actions and interventions on a cyclical basis.

This allows them to make incremental changes over time in soil and water management practices, cropping

and livestock management and natural resources management, within the limits of their own resources, vision

and motivation. This provides a viable model for CCA implementation and financing at smallholder level.

Recent participatory impact assessments have shown remarkable improvements in resilience in the space of

just one to two years of focussed local action.

Introduction

A current Water Research Commission adaptive research process entitled “Collaborative knowledge creation

and mediation strategies for the dissemination of Water and Soil Conservation practices and Climate Smart

Agriculture in smallholder farming systems”is exploring best practice options for climate resilient agriculture

for smallholders and evaluating the impact of implementation of a range of these practices on the resilience of

agriculture based livelihoods. Alongside this, a decision support methodology and system has been designed to

assist smallholdersand the facilitators who support them to make informed and appropriate decisions about

choices of a ‘basket of options’ for implementation at a local level.

The research process is broadly divided into three elements for purposes of clarity, although allthree elements

are tackled concurrently:

1. Community climate change adaptation process design

2. Climate resilient agricultural practices and

3. A decision support system.

In this article we focus on the design of the community level process.

Community climate change adaptation process design

This consistsbroadly of:

1. Situation and vulnerability assessments; baselines and farmer typologies

2. Climate Change dialogues; Exploration of climate change impacts, adaptive strategies and

prioritization of adaptive measures and

3. Participatory impact assessments: Resilience snapshots

NOTE: The vulnerability and participatory impact assessment methodologies will be discussed in two follow-up

articles

Climate change dialogues

A participatory methodology has been developed to allow groups of farmers to explore the impacts of climate

change, potential adaptive strategies and to prioritize local adaptation measures. Seven community level

workshops have been conducted across three provinces, involving around 250 participants. The table below

provides a summary of this community level analysis

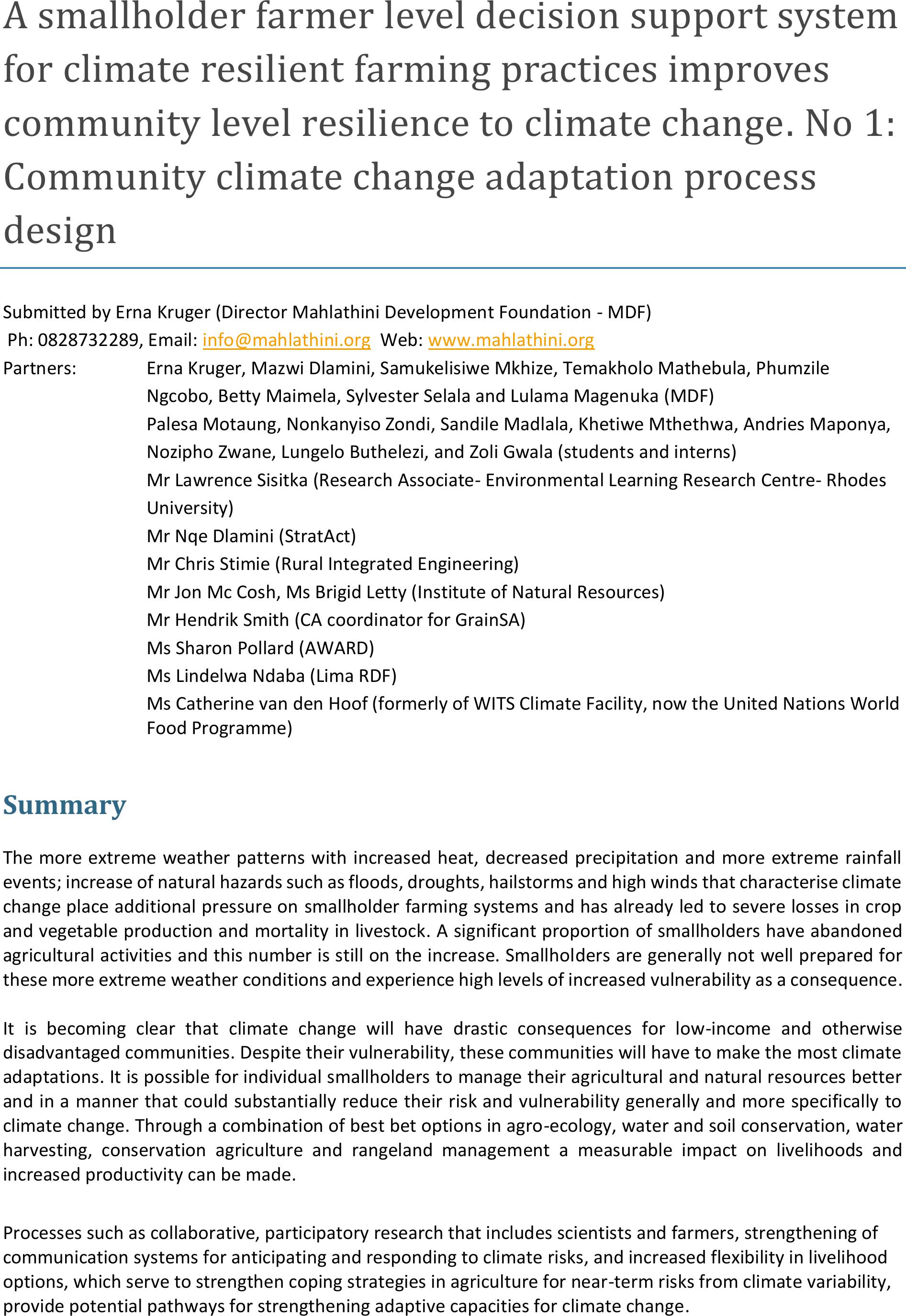

Table 1: Summary of climate change impacts from community level workshops (2018)

Climate change impacts on livelihoods and farming

KZN

EC

Limpopo

Water

Less water in the landscape;

streams and springs dry up,

borehole run dry, soils dry out

quickly after rain

Less water in the landscape; streams

and springs dry up, borehole run dry,

soils dry out quickly after rain

Less water in the landscape; streams

and springs dry up, borehole run dry,

soils dry out quickly after rain

Dams dry up

Dams dry up

Dams dry up

Municipal water supply becoming

more unreliable

Municipal water supply becoming

more unreliable

Municipal water supply becoming

more unreliable;

Need to buy water for household use

–now sometimes for more than 6

months of the year

RWH storage only enough for

household use.

Soil

More erosion

More erosion

More erosion

Soils becoming more compacted

and infertile

Soils becoming more compacted and

infertile

Soils becoming more compacted and

infertile

Soils too hot to sustain plant growth

Cropping

Timing for planting has changed-

later

Timing for planting has changed-

later

Can no longer plant dryland maize

All cropping now requires irrigation –

even crops such as sweet potato

Drought tolerant crops such as

sorghum and millet grow- but severe

bird damage

Heat damage to crops

Heat damage to crops

Heat damage to crops

Reduced germination and growth

Reduced germination and growth

Reduced germination and growth

Seeding of legumes becoming

unreliable

Seeding of legumes becoming

unreliable

Seeding of legumes becoming

unreliable

Lower yields

Lower yields

Lower yields

Winter vegetables don’t do well -

stress induced bolting and lack of

growth

More pests and diseases

More pests and diseases

More pests and diseases

Loss of indigenous seed stocks

Loss of indigenous seed stocks

Livestock

Less grazing; not enough to see

cattle through winter

Less grazing; not enough to see cattle

through winter

Less grazing; not enough to see cattle

through winter

More disease in cattle and heat

stress symptoms

More disease in cattle and heat

stress symptoms

More disease in cattle and heat

stress symptoms

Fewer calves

Fewer calves

Fewer calves

More deaths

More deaths

More deaths

Natural

resources

Fewer trees; too much cutting for

firewood

Fewer trees; too much cutting for

firewood

Fewer trees; too much cutting for

firewood

Decrease in wild animals and

indigenous plants

Decrease in wild animals and

indigenous plants

Decrease in wild animals and

indigenous plants

Increased crop damage from wild

animals such as birds and

monkeys

Increased crop damage from wild

animals such as birds and monkeys

Increased crop damage from wild

animals such as birds and monkeys

Availability of indigenous

vegetables has decreased

No longer able to harvest any

resources due to scarcity

Increased population puts pressure

on resources

Social

More diseases

More diseases

More diseases

Increased poverty and hunger

Increased poverty and hunger

Increased poverty and hunger

Increased crime and reduced job

opportunities

Increased crime and reduced job

opportunities

Increased crime and reduced job

opportunities

Increased food prices

Increased conflict

Inability to survive

Although the impacts discussed were similar across the three provinces, the severity of these changes are a lot

more obvious in Limpopo.

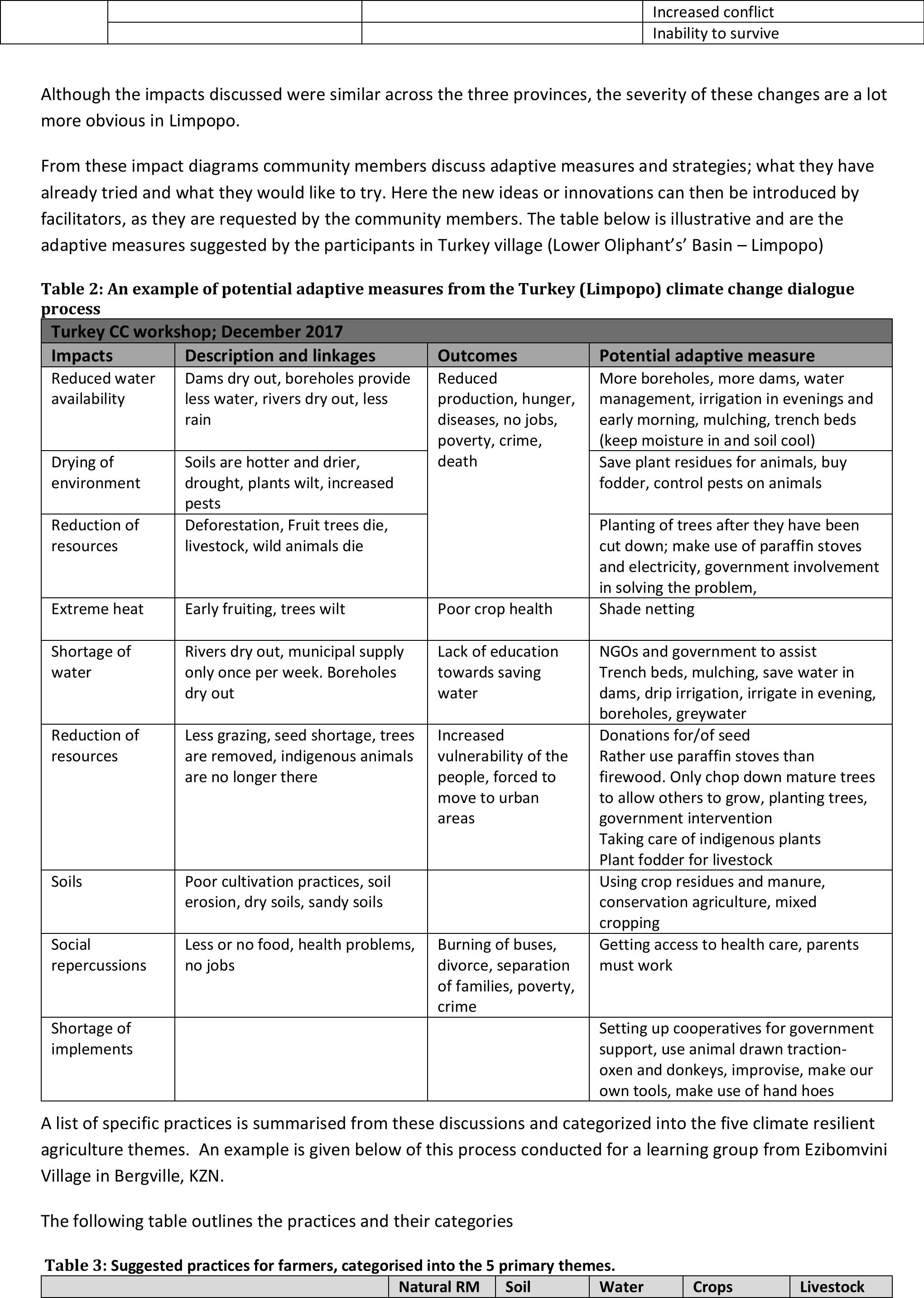

From these impact diagrams community members discuss adaptive measures and strategies; what they have

already tried and what they would like to try. Here the new ideas or innovations can then be introduced by

facilitators, as they are requested by the community members. The table below is illustrative and are the

adaptive measures suggested by the participants in Turkey village (Lower Oliphant’s’ Basin – Limpopo)

Table 2: An example of potential adaptive measures from the Turkey (Limpopo) climate change dialogue

process

Turkey CC workshop; December 2017

Impacts

Description and linkages

Outcomes

Potential adaptive measure

Reduced water

availability

Dams dry out, boreholes provide

less water, rivers dry out, less

rain

Reduced

production, hunger,

diseases, no jobs,

poverty, crime,

death

More boreholes, more dams, water

management, irrigation in evenings and

early morning, mulching, trench beds

(keep moisture in and soil cool)

Drying of

environment

Soils are hotter and drier,

drought, plants wilt, increased

pests

Save plant residues for animals, buy

fodder, control pests on animals

Reduction of

resources

Deforestation, Fruit trees die,

livestock, wild animals die

Planting of trees after they have been

cut down; make use of paraffin stoves

and electricity, government involvement

in solving the problem,

Extreme heat

Early fruiting, trees wilt

Poor crop health

Shade netting

Shortage of

water

Rivers dry out, municipal supply

only once per week. Boreholes

dry out

Lack of education

towards saving

water

NGOs and government to assist

Trench beds, mulching, save water in

dams, drip irrigation, irrigate in evening,

boreholes, greywater

Reduction of

resources

Less grazing, seed shortage, trees

are removed, indigenous animals

are no longer there

Increased

vulnerability of the

people, forced to

move to urban

areas

Donations for/of seed

Rather use paraffin stoves than

firewood. Only chop down mature trees

to allow others to grow, planting trees,

government intervention

Taking care of indigenous plants

Plant fodder for livestock

Soils

Poor cultivation practices, soil

erosion, dry soils, sandy soils

Using crop residues and manure,

conservation agriculture, mixed

cropping

Social

repercussions

Less or no food, health problems,

no jobs

Burning of buses,

divorce, separation

of families, poverty,

crime

Getting access to health care, parents

must work

Shortage of

implements

Setting up cooperatives for government

support, use animal drawn traction-

oxen and donkeys, improvise, make our

own tools, make use of hand hoes

A list of specific practices is summarised from these discussions and categorized into the five climate resilient

agriculture themes. An example is given below of this process conducted for a learning group from Ezibomvini

Village in Bergville, KZN.

The following table outlines the practices and their categories

Table 3: Suggested practices for farmers, categorised into the 5 primary themes.

Natural RM

Soil

Water

Crops

Livestock

Shade Cloth Tunnels

Bed design

Mulching

Natural pest and diseases

Rainwater harvesting

Trench bed

Composting

Conservation Agriculture

Fodder crops

Underground water tank

Mixed cropping

Conservation of wetlands and streams

Burying of disposable pampers

Reducing burning of grazing veld

Greywater use

Participants then prioritize these practices in order of

importance for implementation and change as a group.This

depends on local conditions such as drought, harsh weather

conditions and the like.The preference ranking for this

group was as follows:

1. Underground rainwater harvestingtanks

2. Shade cloth tunnels

3. Trench beds

4. Mulching

5. Natural pest and disease control

6. Mixed cropping(fields and gardens)

7. Compost

8. Fodder crops

9. Conserving wetlands and streams

Right: Sylvester and Temakholo from MDF, facilitating the

prioritization of practices

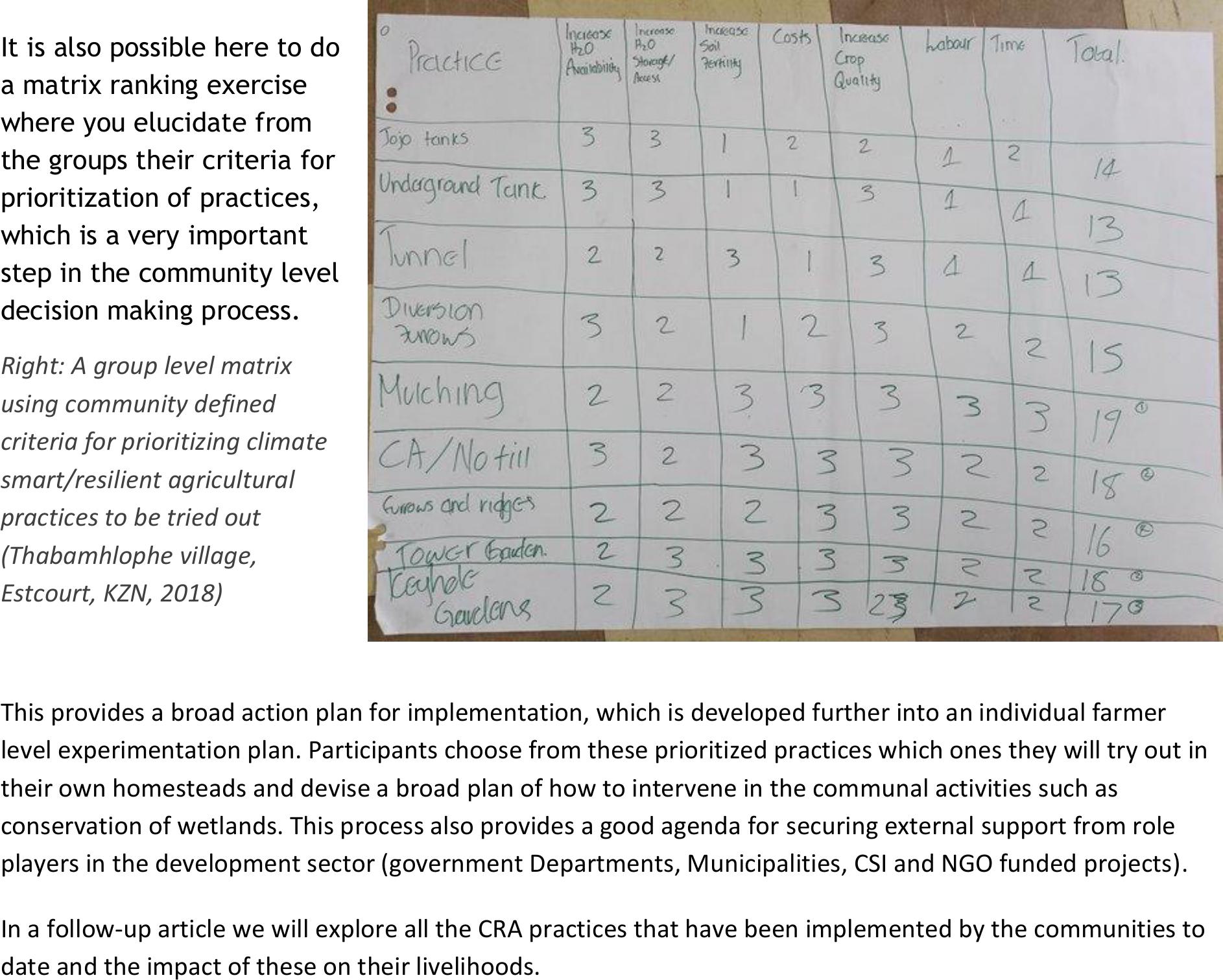

It is also possible here to do

a matrix ranking exercise

where you elucidate from

the groups their criteria for

prioritization of practices,

which is a very important

step in the community level

decision making process.

Right: A group level matrix

using community defined

criteria for prioritizing climate

smart/resilient agricultural

practices to be tried out

(Thabamhlophe village,

Estcourt, KZN, 2018)

This provides a broad action plan for implementation, which is developed further into an individual farmer

level experimentation plan. Participants choose from these prioritized practices which ones they will try out in

their own homesteads and devise a broad plan of how to intervene in the communal activities such as

conservation of wetlands. This process also provides a good agenda for securing external support from role

players in the development sector (government Departments, Municipalities, CSI and NGO funded projects).

In a follow-up article wewill explore all the CRA practices that have been implemented by the communities to

date and the impact of these on their livelihoods.