1

MICROFINANCE HANDBOOK FOR SMALLHOLDER FARMERS IN

SOUTH AFRICA. February 2023

Written by Nqe Dlamini and Erna Kruger

With support from the Water Research Commission, in partial fulfilment of

Deliverable 3 for Project number C2022/2023-00746.

Contents!

Foreword................................................................................................................................................3

Acknowledgements................................................................................................................................3

List of Abbreviations..............................................................................................................................4

Executive Summary...............................................................................................................................5

1.Background....................................................................................................................................5

1.1.Community-based microfinance services...................................................................................6

1.1.1.Burial societies.....................................................................................................................10

1.1.2.Stokvels................................................................................................................................10

1.1.3.Savings and credit groups.....................................................................................................10

1.1.4.Investment groups................................................................................................................11

1.1.5.Multi-function groups..........................................................................................................11

1.2.Provision methodologies of community-based microfinance services.....................................11

1.2.1.Microfinance NGOs.............................................................................................................11

1.2.2.ROSCAs...............................................................................................................................14

1.2.3.ASCAs................................................................................................................................. 14

1.2.4.VSLAs..................................................................................................................................15

1.3.Making connections.................................................................................................................16

1.3.1.International best practice....................................................................................................17

1.3.2.South African practice..........................................................................................................18

2.Study Aims and Objectives..........................................................................................................20

2.1.Research methodology.............................................................................................................20

2.2.Sampling..................................................................................................................................22

2.3.Data generation methods..........................................................................................................23

2.4.Data analysis............................................................................................................................23

2.5.Results and analysis.................................................................................................................24

2

2.6.Financial Services in the Villages............................................................................................27

2.7.Discussion................................................................................................................................30

2.7.1.Introduction of themes.........................................................................................................32

2.7.2.Discussion of theme 1: social intelligence competency.......................................................33

2.7.3.Discussion of theme 2: cultural competency........................................................................44

2.7.4.Discussion of theme 3: collaborative learning competency.................................................49

2.8.Key lessons...............................................................................................................................57

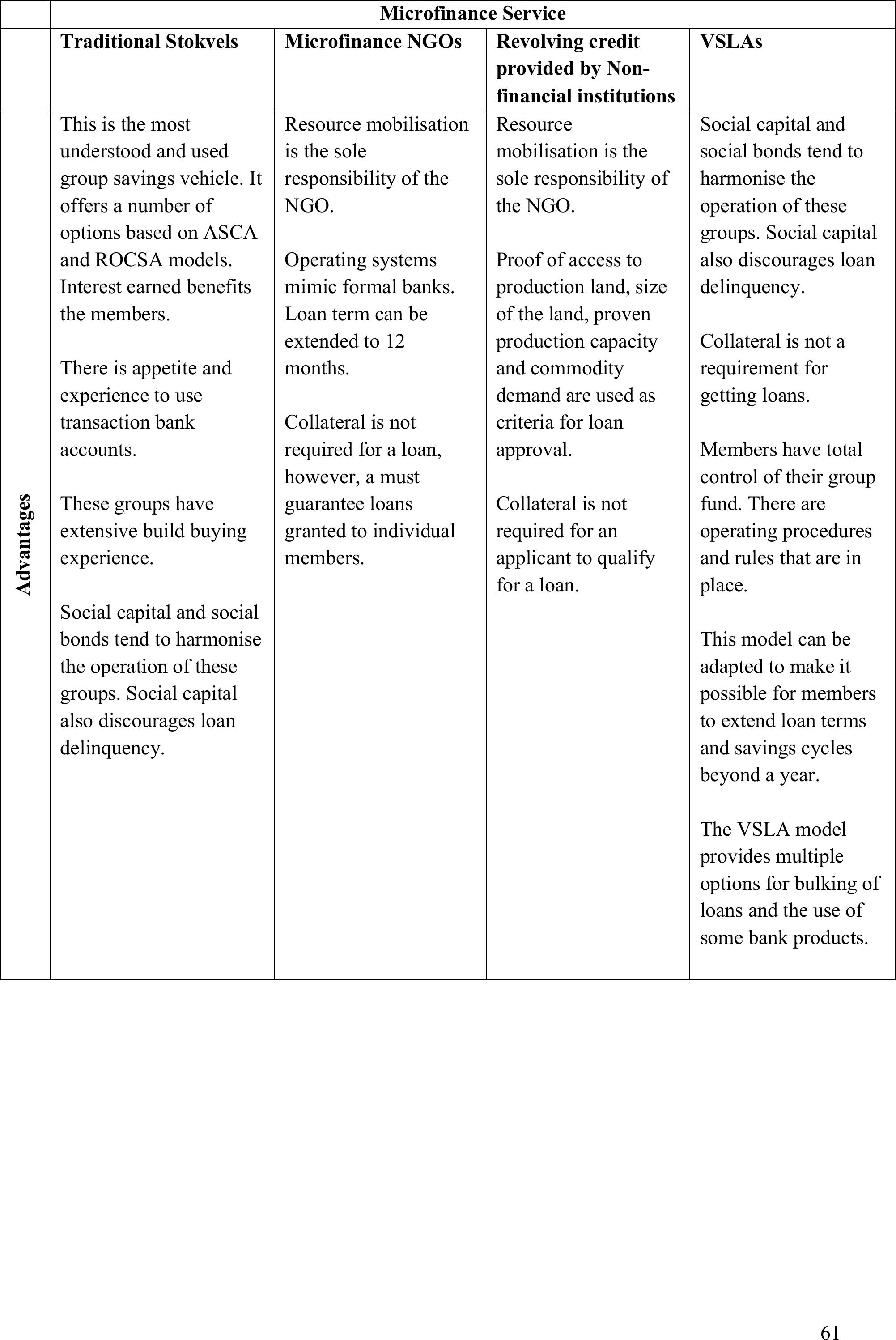

2.9.Microfinance options available for smallholder farmers..........................................................60

3.Governance and Operation of VSLAs..........................................................................................63

3.1.Users of VSLAs.......................................................................................................................63

3.2.Institutional, governance and management structure...............................................................64

3.3.Beneficiation protocols............................................................................................................65

3.4.VSLA operations......................................................................................................................65

3.5.Monitoring and evaluation.......................................................................................................67

3.6.Limitations of the study............................................................................................................67

3.7.Conclusions and future considerations.....................................................................................67

4.Good Practice and Success Factors..............................................................................................68

4.1.Adaptation................................................................................................................................68

4.2.Taking smallholder farmer-operated VSLAs to the next level.................................................69

4.3.Implications for external supporters and donors......................................................................69

References............................................................................................................................................70

Annexure 1: Data Collection Instrument: Questionnaire.....................................................................75

Annexure 2: Data Collection: Focus Group Discussion Schedule.......................................................80

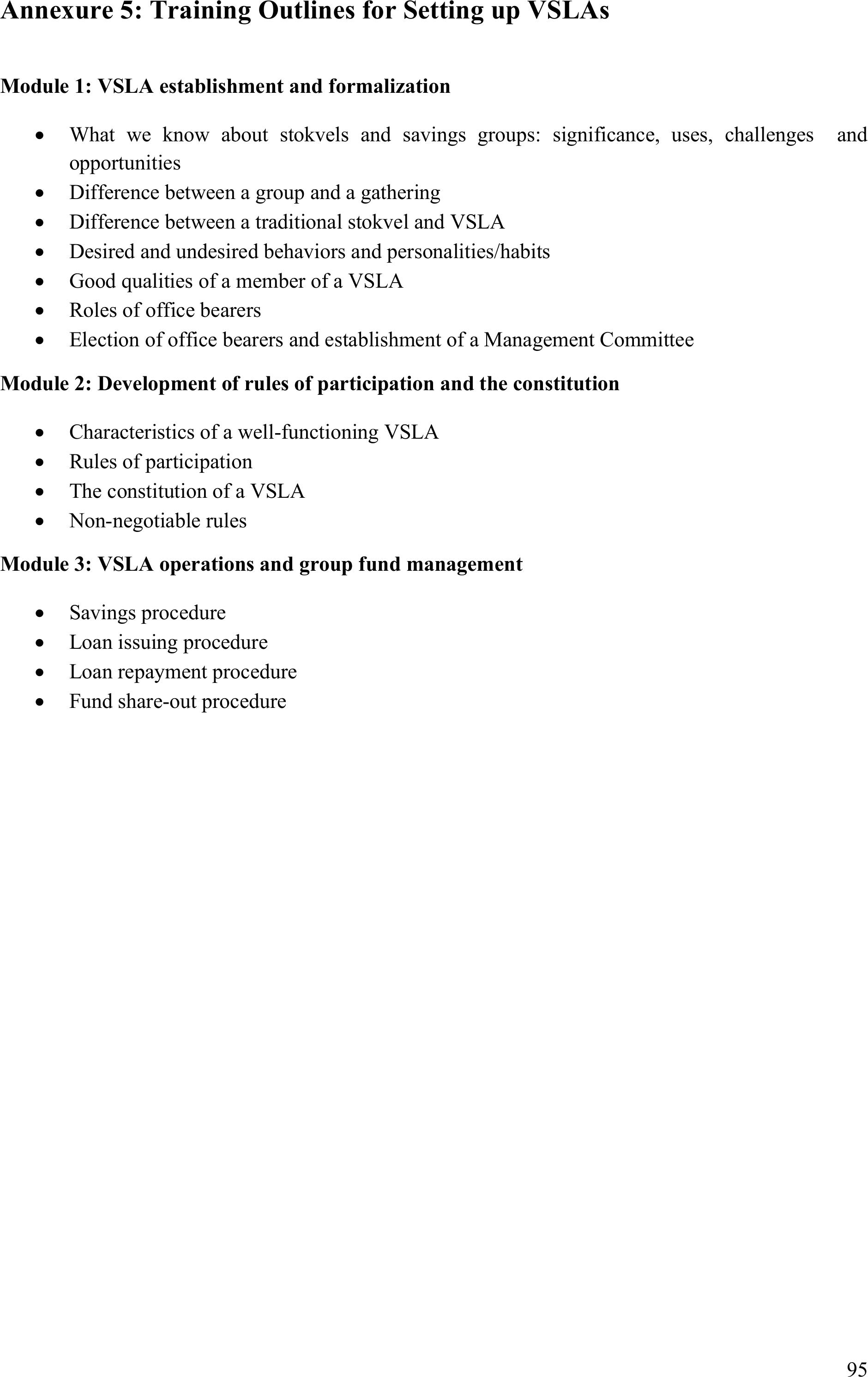

Annexure 3: Contents of a VSLA Constitution and Rules...................................................................84

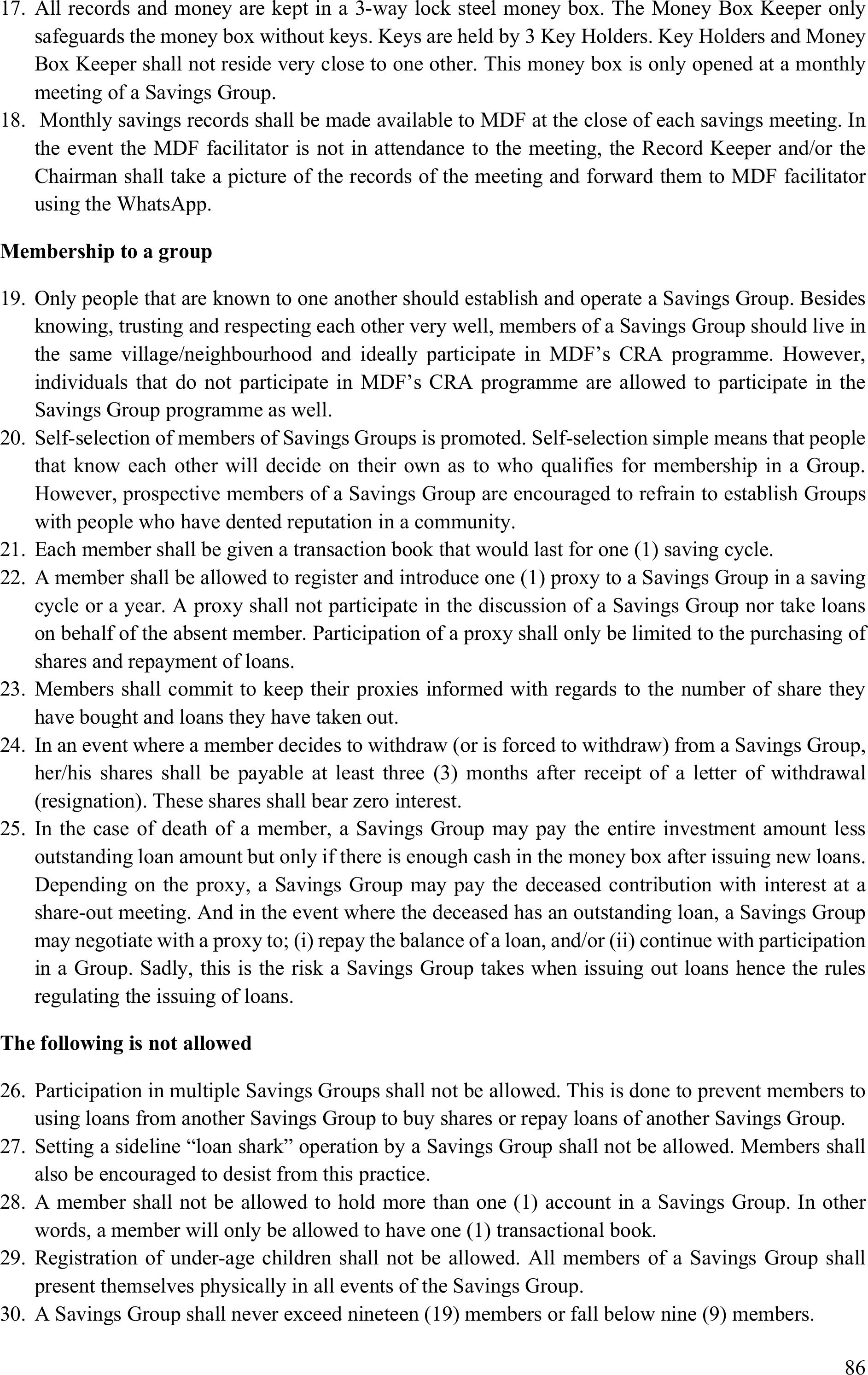

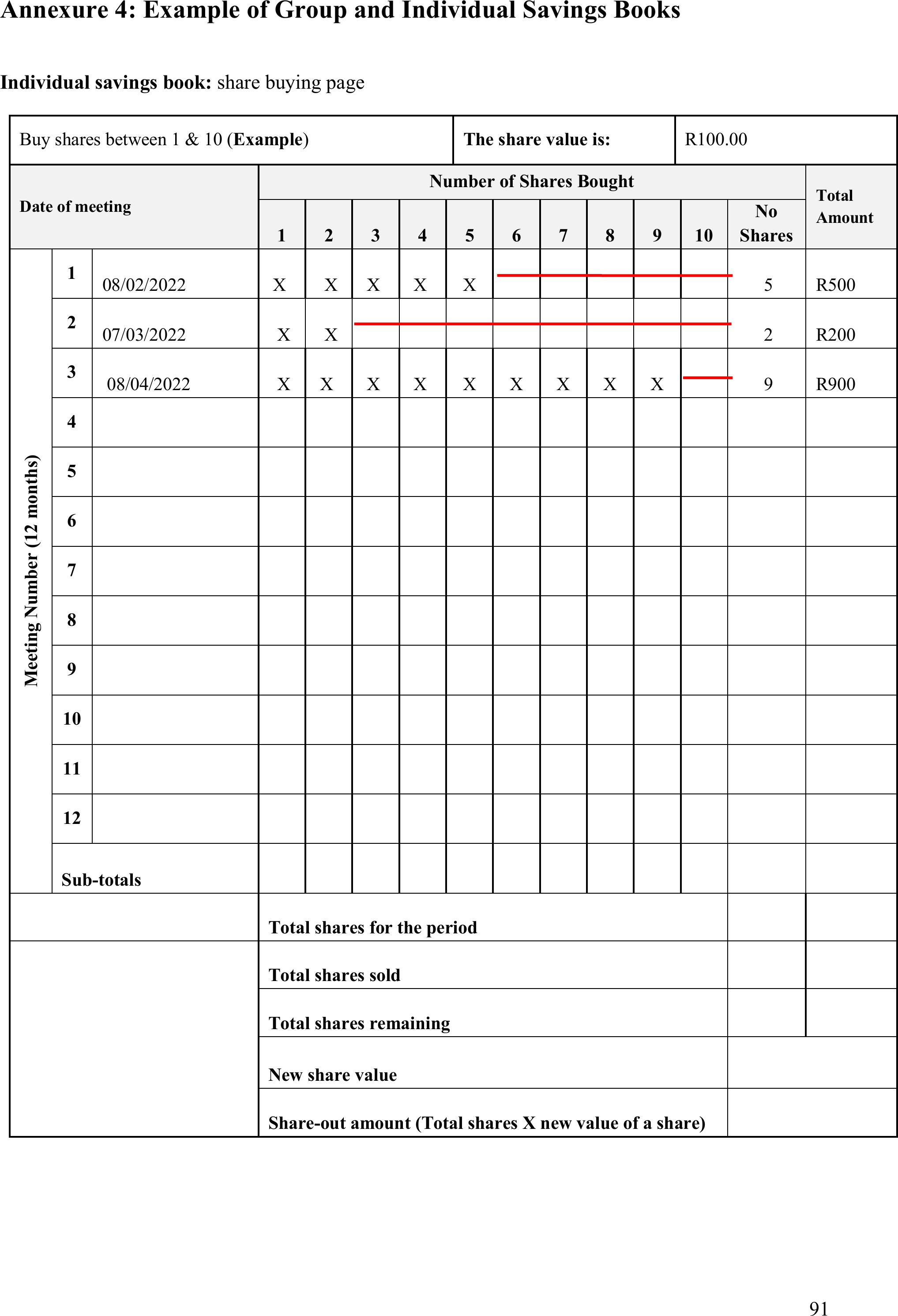

Annexure 4: Example of Group and Individual Savings Books...........................................................91

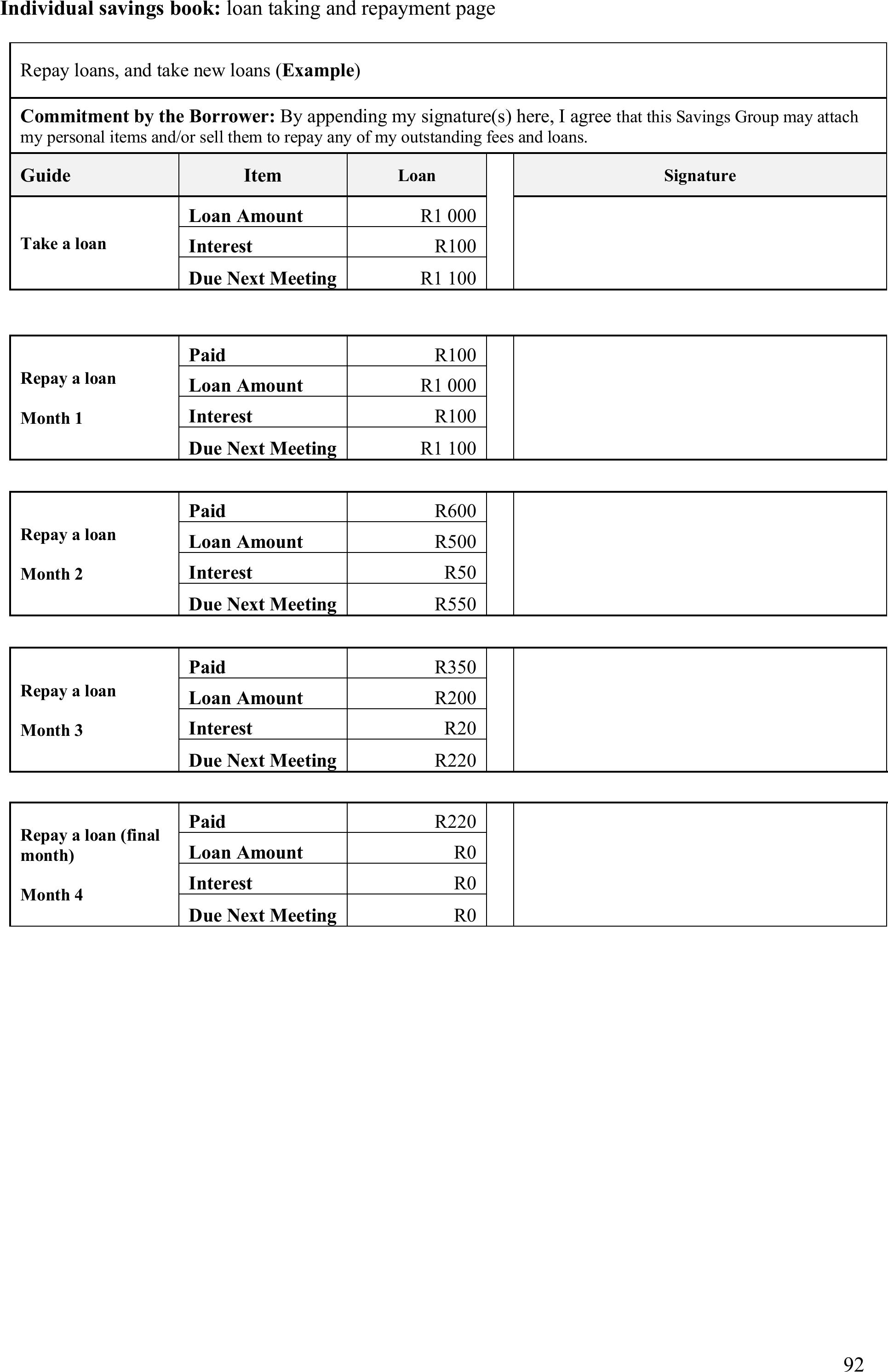

Annexure 5: Training Outlines for Setting up VSLAs.........................................................................95

Annexure 6: Record Keeper Training Outline.....................................................................................96

3

Foreword

This handbook is meant for those individuals and organisations who are interested to understand how

microfinance works for the rural poor in practise. The handbook provides short descriptions and

analysis of services available to the poor and provides comment on best practise in these options.

It also provides a recent study on microfinance options for focus groups in 7 villages across KZN and

Limpopo. In addition, guidance is provided in the implementation of village savings and loan

associations (VSLAs) for those interested in implementation of such processes.

This handbook is the culmination of around 10 years’ worth of implementation and is being published

as one of a series of handbooks and case studies within a Water Research Commission study and

dissemination process entitled “Dissemination and scaling of a decision support framework for CCA

for smallholder farmers in SouthAfrica” (Project number:C2022/2023-00746). As per project cycle

requirements, this handbook in part fulfils the requirements for the deliverable entitled “Handbook on

scenarios and options for successful smallholder financial services within the South Africa”.

Acknowledgements

This research study would not have been possible without the financial support of the Water Research

Commission (WRC) and the dedicated field team employed by Mahlathini Development Foundation

for being there during data collection. The participating smallholder farmers are also gratefully

acknowledged.

4

List of Abbreviations

ASCA

Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations

CARE

Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere

CbCCA

Community-based Climate Change Adaptation

CBDA

Co-operatives Banks Development Agency

CRA

Climate Resilient Agriculture

CRS

Catholic Relief Services

DALRRD

Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development

FGD

Focus Group Discussion

HCD

Human-Centred Design

IE

Informal Economy

ILO

International Labour Organisation

MFI

Micro-financial Institution

NGO

Non-Governmental Organisation

ROCSA

Rotating Savings and Credit Associations

SCG

Savings and Credit Group

SACCO

Savings and Credit Co-operative

SEF

Small Enterprise Foundation

SMME

Small Micro and Medium Enterprise

VSLA

Village Savings and Loans Association

WIEGO

Women in Informal Employment: Globalising and Organizing

WRC

Water Research Commission

5

Executive Summary

In this qualitativestudy we examined microfinance options which are available for smallholder farmers

participating in the Community-based Climate Change Adaptation (CbCCA) programme and to draw

lessons for broader applications. Microfinance is the provision of financial services such as savings,

loans and insurance to people who are too poor to qualify for financial services from formal financial

institutions (Wrenn, 2007). We explored experiences of members participating in Village Savings and

Loans Associations (VSLAs) in the villages whereMahlathini Development Foundation implements

community based climate change adaptation. Human-Centred Design (HCD) was used in the study to

examinedifferent group-based financial services, identify challenges and dissect microfinance options

that savings groups present to smallholder farmers. Data was generated through in-depth interviews

followed by seven focus group discussions in selected rural communities in KwaZulu Natal and

Limpopo provinces.

The study found that group-based savings provide opportunities for integrating VSLAs into smallholder

farming and the rural enterprise development agenda.This is because VSLAs provide an alternative

and structured system for providing accountable and transparentfinancial services that is backed by

decades of practice and has a good track record for the attainment of tangible livelihood outcomes.

However, this study concludes that further research is still required to use the wealth of experiences of

group-based savingsin designing additional responsive financial services for smallholder farmers.

1.Background

The financial services landscape in developing countries such as South Africa is a complex one. There

are formal and informal financial services offered by different institutions or entities to different income

levels. Generally, underserved populations are serviced primarily by community-based informal

financial institutions, unregulated money lenders and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). South

African government have a basket of financial servicesavailable to qualifying smallholder farmers.

These financial services are provided mainly by the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural

Development (DALRRD), Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA), Land Bank and Small

Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA).Our interest in VSLAs was triggered by the unsung role of these

groups in generating financial and entrepreneurship education and practice that is fit-for-purpose despite

the brutal economic realities of the poor.

Financial inclusion aims to contribute to long-term sustainable human development impacts. Given the

uncertainties faced by smallholder farmers participating in climate change adaptation programmes,

adaptive planning approaches hold promise to connect planning, implementation and evaluation of

community-based informal financial institutions operated by smallholder farmers within this process.

Therefore, in this study we set out to examine microfinance options which are available for smallholder

farmers participating in the Community-based Climate Change Adaptation (CbCCA) and to draw

lessons for broader applications. The study aimed to understand practices happening in VSLAs and

similar community-based informalfinancial institutions for the purposes of suggesting best practise

options in microfinance for smallholder farmers in South Africa.

6

There are two broad categories of community-based informal microfinance institutions. These

categories are Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) and Accumulating Savings and

Credit Associations (ASCAs). Members of a ROSCA contribute an equal amount of money on a regular

basis, typically on a monthly basis. In each meeting,a different member picks up the pre-determined

lump sum. This practice continues until every member of a group has received his or her payout.

ROCSAs are also known as “merry-go-rounds”. ASCAs use members’ regular savings to build a group

fund that is used to provideshort-term micro-loans to the members of the group. At the endof a savings

cycle, which is usually a year; the group dissolves and distributes group funds proportionally to the

deposits of individual members. Community-based financial services and institutions are discussed later

in this report.

The main problem is that many development programmes that seek to improve incomes of vulnerable

households and their livelihoods are struggling to mainstream the microfinance aspects of their

interventions, especially for rural low-income earners. Worse, smallholder farmers remain with the

stigma of low productivity. The South African smallholder farmer support programmes fail smallholder

farmers on multiple levels, but mostly on access to financial services, information, education,

technology and markets.

Microfinance institutionsare not widely promoted and used for broad-based SMME development

objectives and appear to be marginalised. Besides short-term project based funding sourced mainly by

NGOs, there is no evidence of support provided by the South African government. This means that the

practice and wealth of experience of community-based informal financial institutions such as the

VSLAs is devalued, and as a consequence, learning opportunities that promise to improve and facilitate

broader financial inclusion objectives are missed.

The inspiration of this study is drawnmainly from the role these groups play specifically in the rural

development space in South Africa. This research study argues that VSLAs can help smallholder

farmers with some financial services which support financing of their operations and meaningful

interaction with local markets. Such groups have proved helpful to millions of under-banked households

in developing countries worldwide, allowing them to save and borrow money outside the formal

banking system(CARE, 2017; FAO, 2016; Alkire et al., 2013).

1.1.Community-based microfinance services

The role and the importance of community-based financial institutions such as VSLAs and Stokvels in

national economies across the globe have been recorded by many development institutions and

researchers in the field of community economic development(Entz et al., 2016; Custers, 2016;

Dallimore, 2013; Allen, 2018). However, the interest of this section is to describe the relationship that

these institutions have with the informal economy (IE). Drawing from the International Labour

Organisation (ILO) (2002), Women in Informal Employment: Globalising and Organizing (WIEGO)

provides the most practical description of the informal economy. WIEGO sees informal economy as

constituted largely by unincorporated small enterprises that may also be unregistered, however, the

informal economy is not just the bottom of the pyramid but it is the broad base of the economy (WIEGO,

in IIED, 2016).

7

According to Clause 3 of the 2002 Resolution of the ILO on Decent Work and the Informal Economy

(IE), informal economy refers to:

“... all economic activities by workers and economic units that are – in law or in practice –

not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements. Their activities are not

included in the law, which means that they are operating outside the formal reach of the law;

or they are not covered in practice, which means that – although they are operating within

the formal reach of the law, the law is not applied or not enforced; or the law discourages

compliance because it is inappropriate, burdensome, or imposes excessive costs” (ILO,

2002).

Box 1: Definition of informal economy

Community-based financial institutions remain a lifeline for many poor and vulnerable households

which are essentially marginalised and excluded. Based on this lifeline narrative, these groups are

purported as safety nets which mitigate the negative consequences of spatial dislocation of rural

settlement to urban centres. Common bonds, be it occupational or geographical (community) are known

for binding members of these groups together (CBDA, 2016). The significance of common bonds is

that it determines the level of participation and discipline as well as mitigating risks stemming from

group dynamics.

These groups are specifically known for cushioning vulnerable households against food insecurity,

constrained access to productive land, lack of collateraland low levels of potential profit. The ugly

consequence of spatial dislocation is that it imposes higher transactional costs on rural households when

compared to their urban counterparts. Each month, millions of South Africans meet in their respective

groups to save and to grant micro-loans that borrowers then use primarily for consumption smoothing,

but also to manage their informal businesses.

8

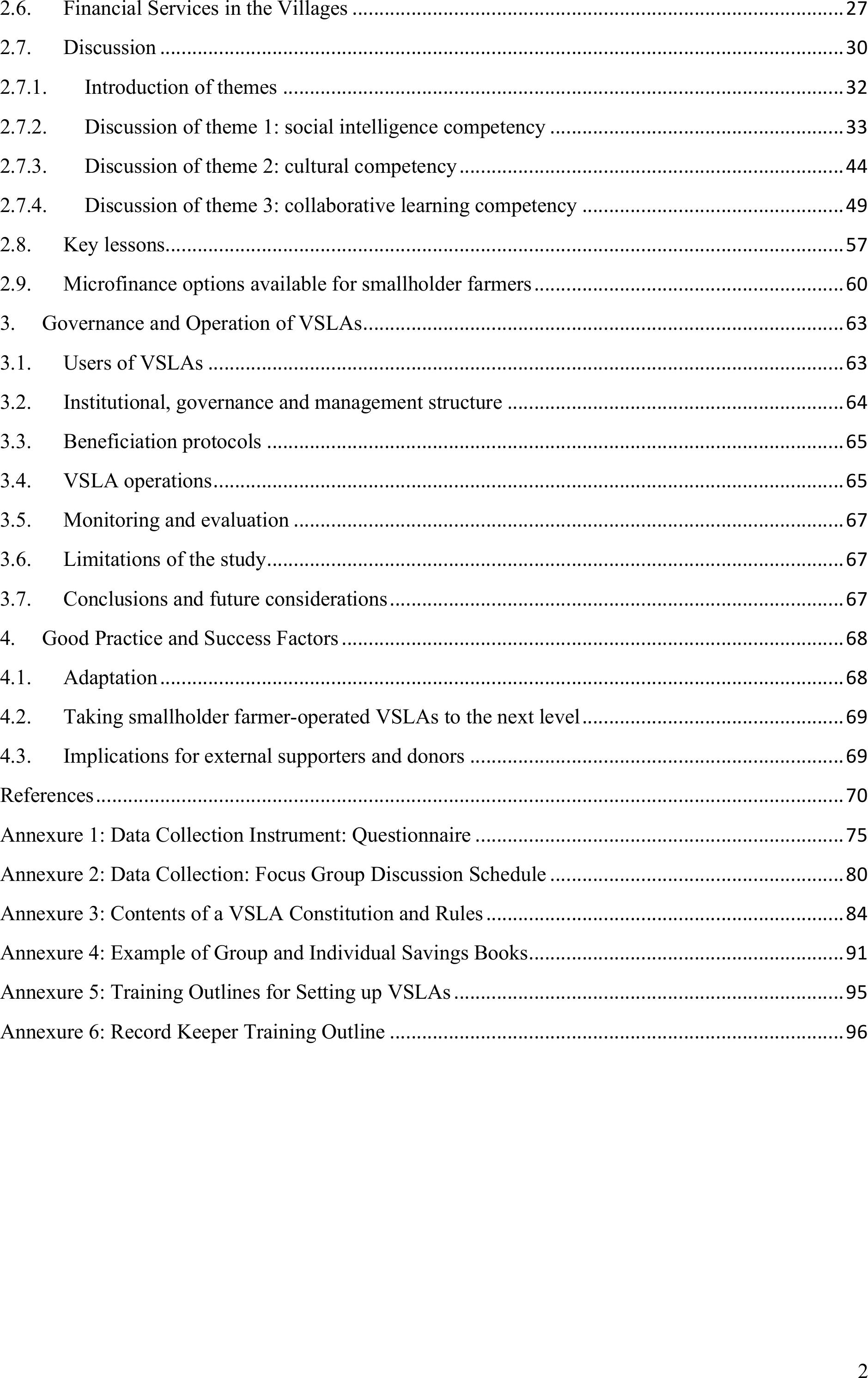

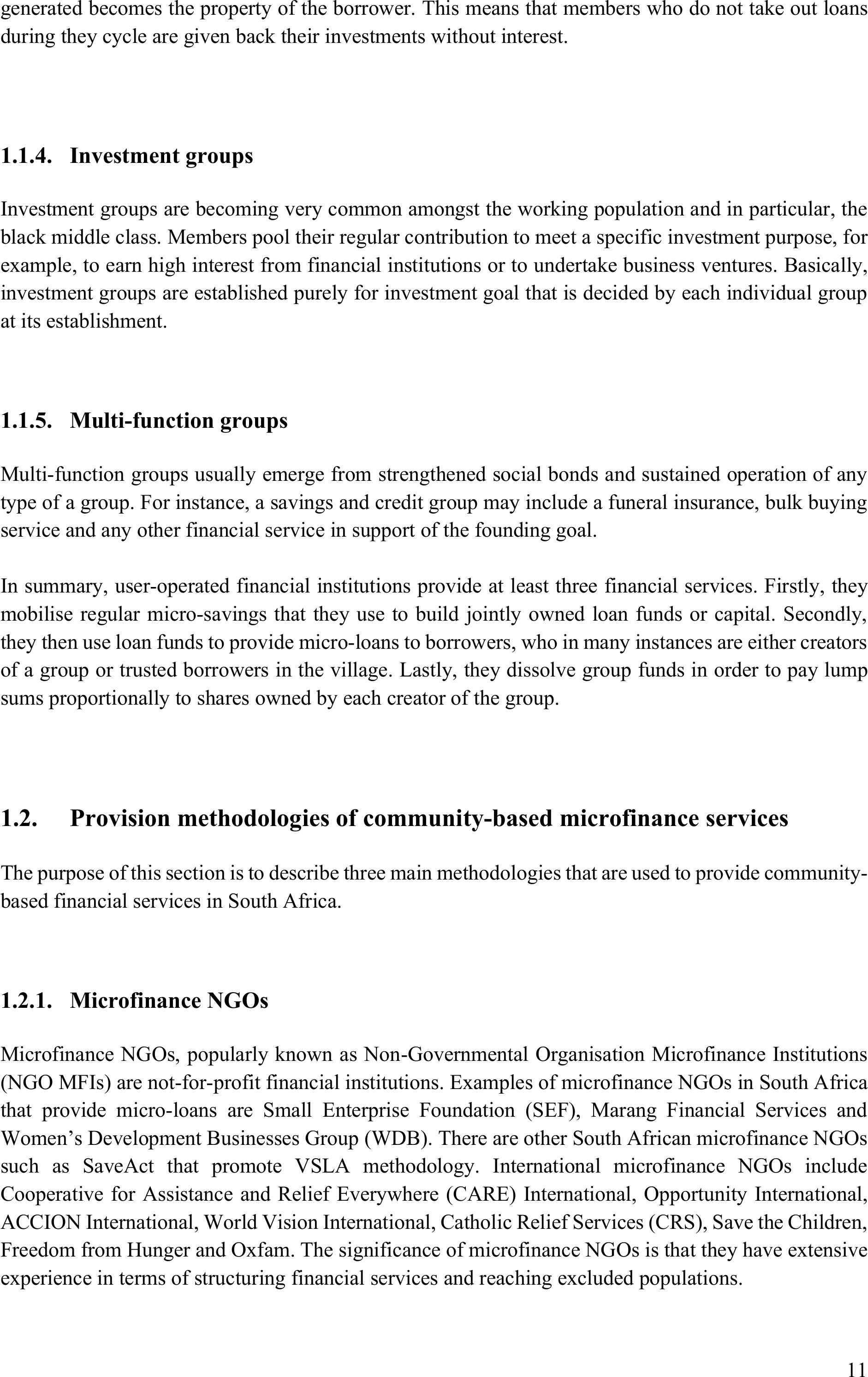

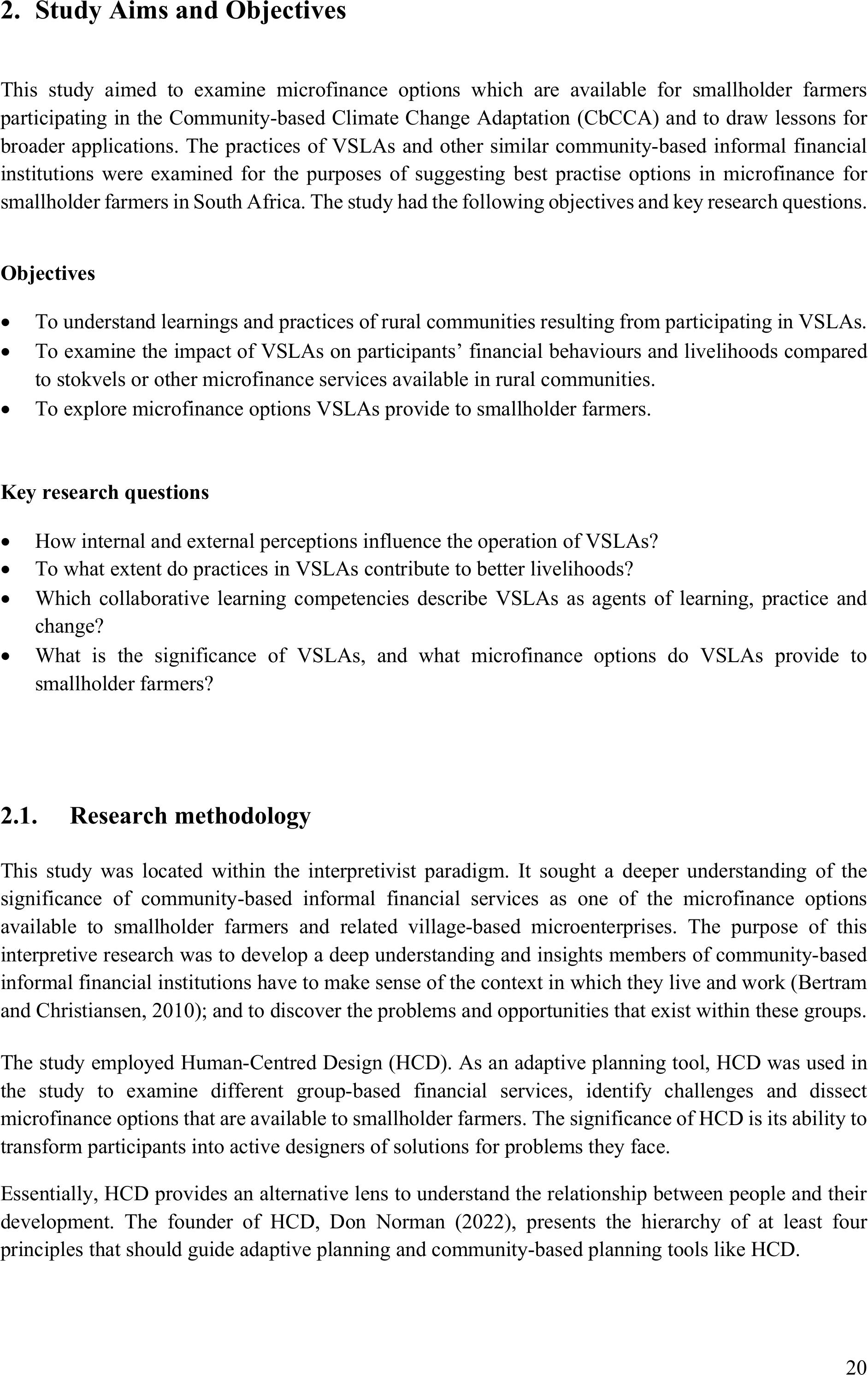

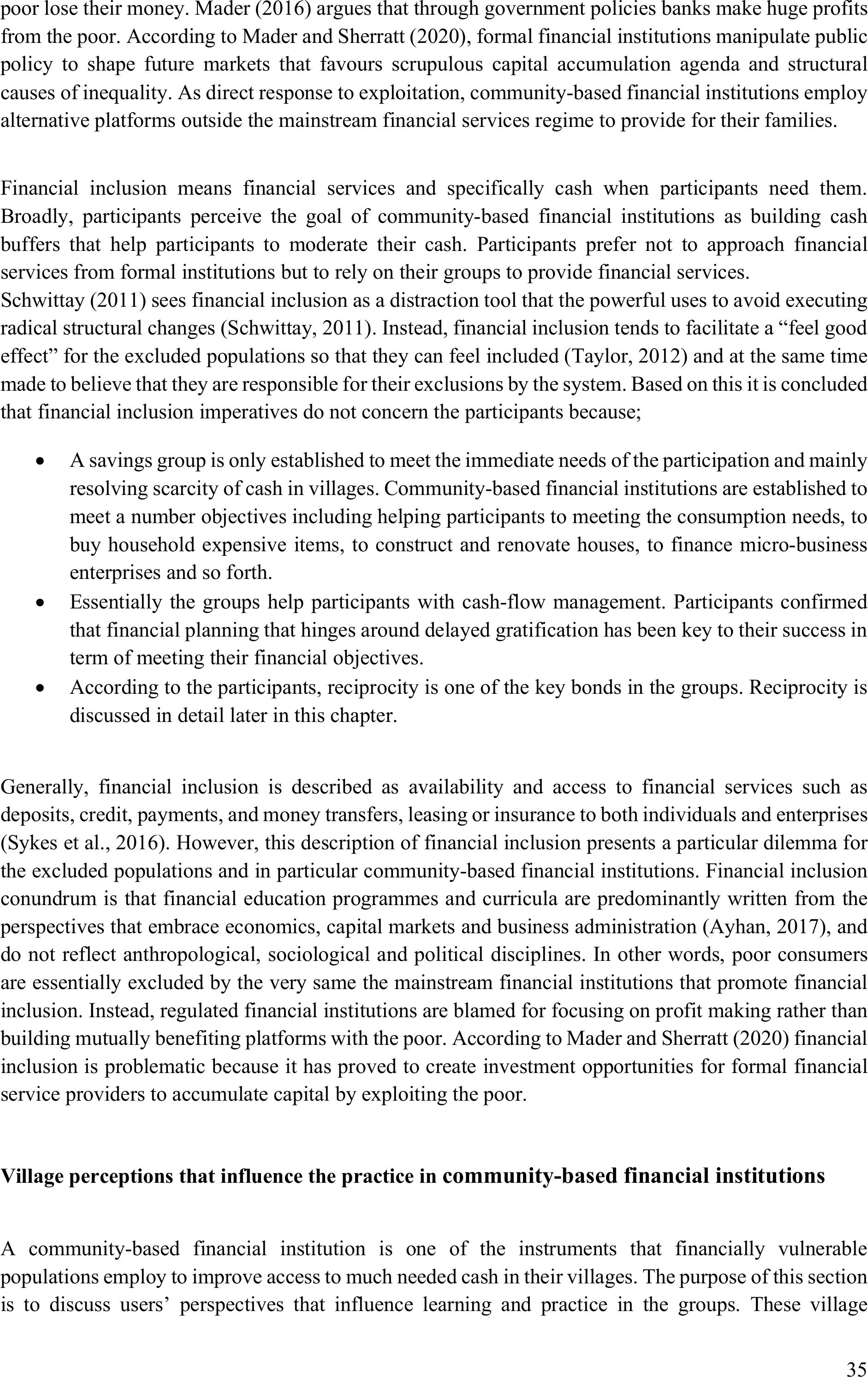

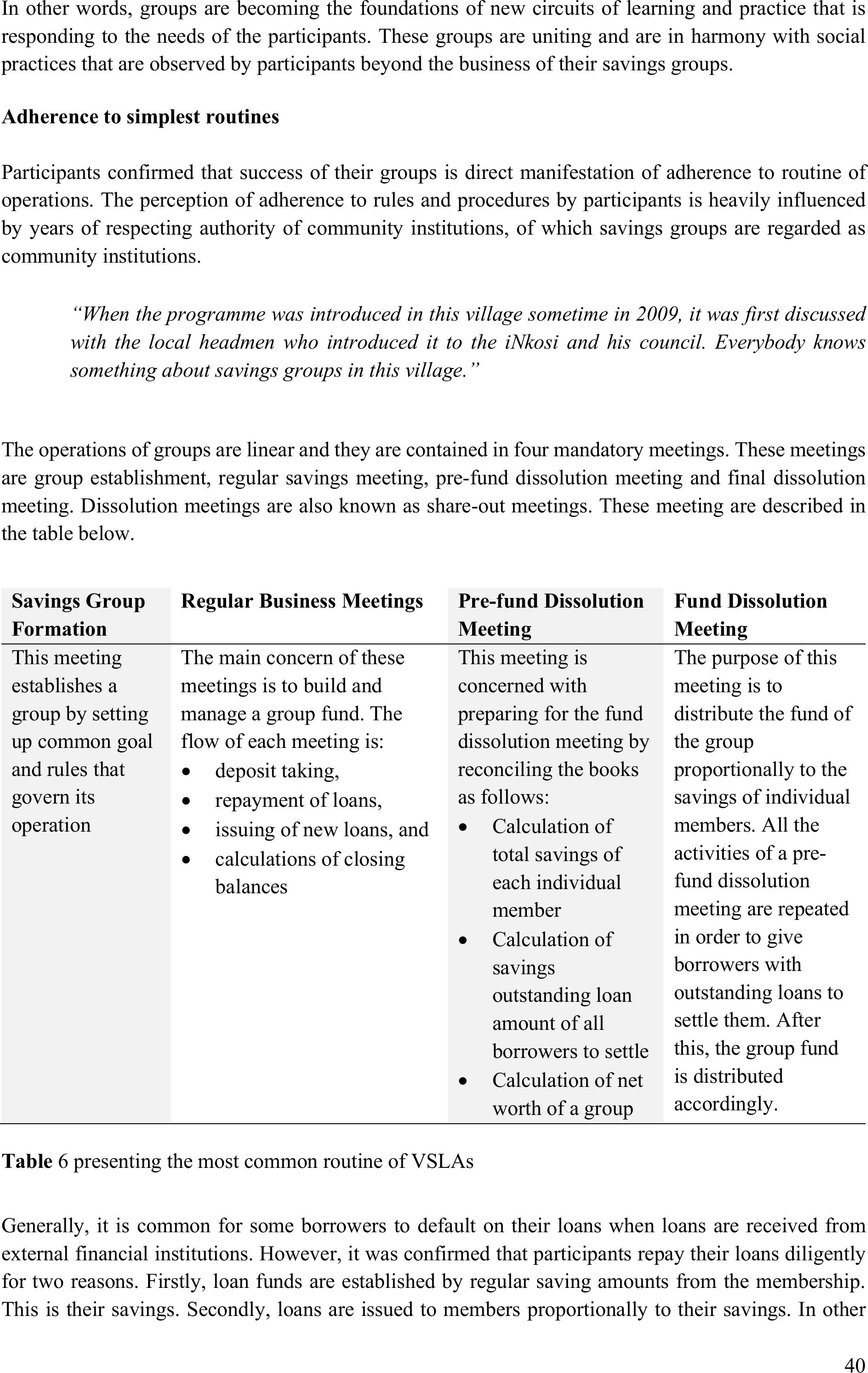

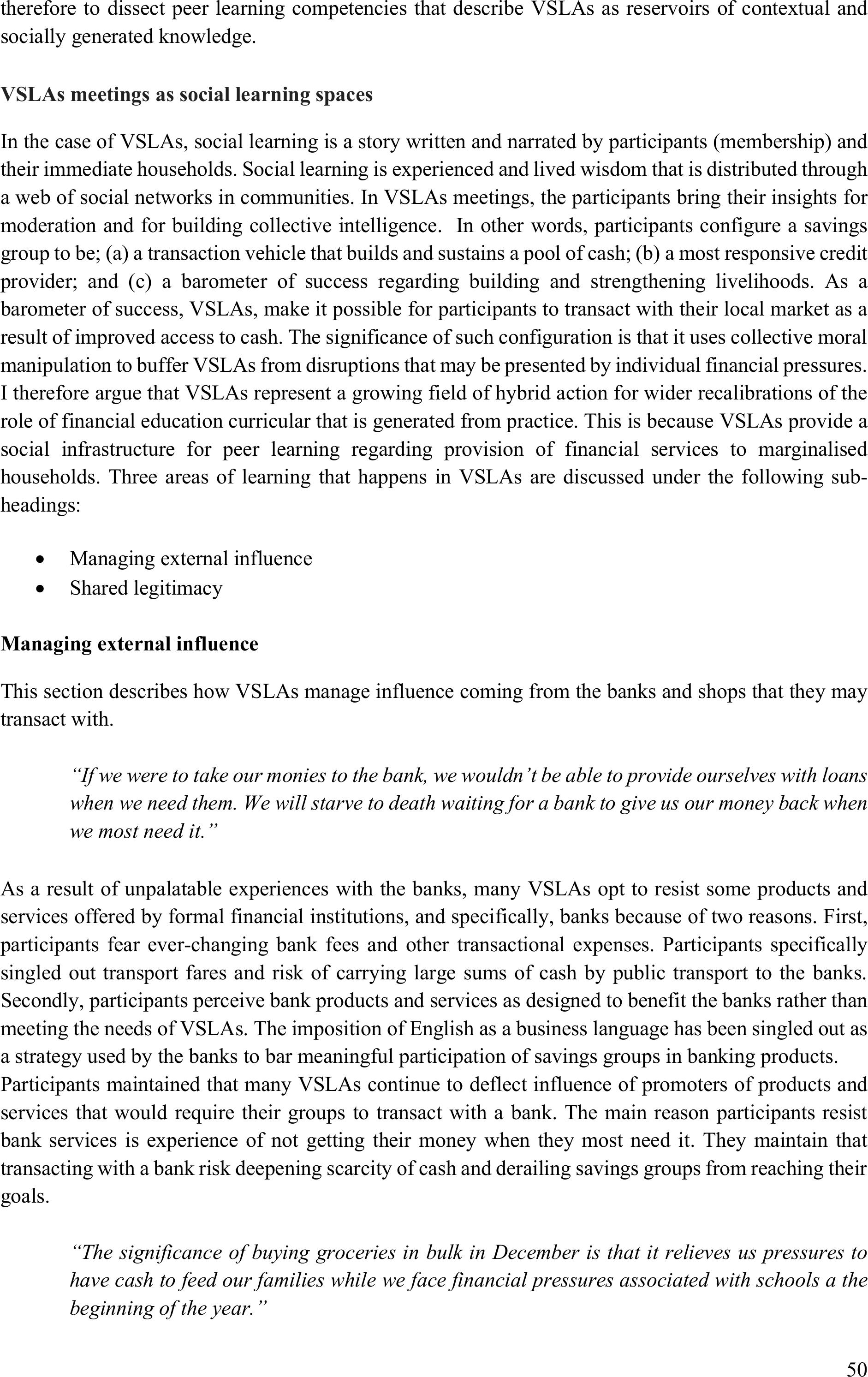

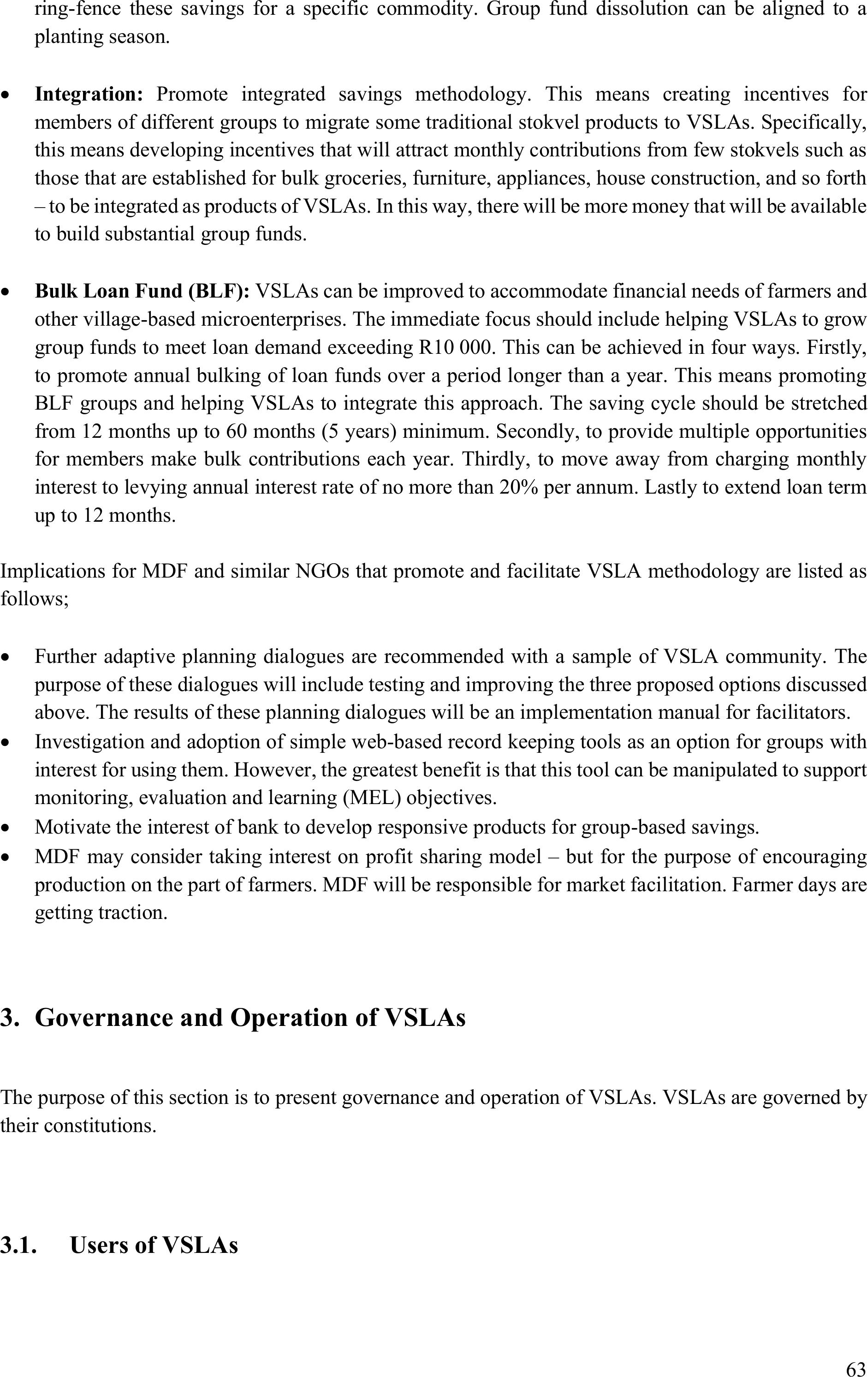

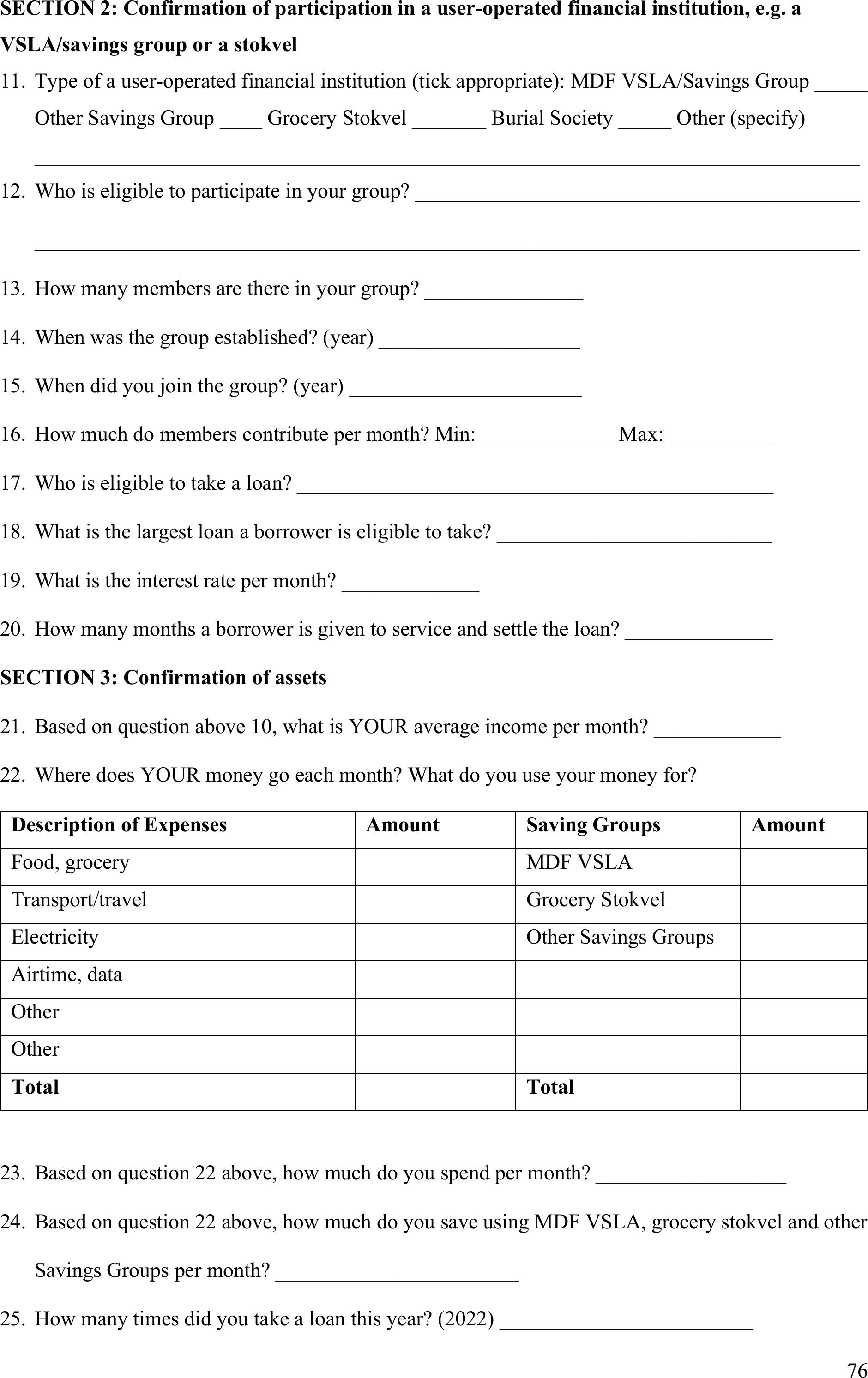

Figure 1showing providers of microfinance services, adapted from Ledgerwood (2013)

As shown in figure 1 above, today the term microfinance describes a basket of financial services which

include micro-loans, micro-savings and micro-insurance designed to serve not only microenterprises

but the unbanked and under-banked populations (Collinset al., 2009). However, Kirsten and van Zyl

(1998) point out that access to insurance is almost non-existent for smallholder farmers as it is either

unaffordable and/or insurance providers do not have appetite to service small premium payers. Outside

of the formal financial sector, community-based financial institutions have been operating for decades.

The 1990s were characterised by rapid growth of microfinance financial institutions providing a basket

Providers of

microfinance

services

Regulated

financial

institutions

Community-

based informal

financial

institutions

Development

Financial Institutions

(DFIs)

South African DFIs, e.g.

iThala Bank, DBSA, Land

Bank, SEFA

Commercial banks

and insurers

Micro-finance

Institutions (MFIs)

•Financial co-ops

•Micro-loan providers

•SACCOs

•Microfinance NGOs

Individual

providers

Indigenous

groups

Facilitated

groups

•Money lenders

•Shop owners

•Families

•Friends

•Burial societies

•Stokvels (ROCSAs &

ASCAs)

VSLAs

South African banks, e.g.

FNB, Nedbank, etc.

Financial

intermediaries

•Agents

•Franchises

•Retailers

9

of services to the poor (Ryne, 2014). Description of community-based financial institutions and mainly

ROCSAs, ASCAs, traditional stokvels and VSLAs are discussed later in the report.

Rutherford (2000) echoes that poor people use community-based financial institutions as livelihood

strategies for savingmoney for life-cycle events such aschildbirth, burials, traditional ceremonies,

marriages, construction of dwellings; and to mitigate disruptive shocks that risk depleting the financial

resource base of vulnerable households. Similarly, Storchi (2018) and Ngcobo (2018) confirm the

positive impact of these groups with regards to betterment of dwellings and income generating

initiatives.

Internationally, VSLAs are praised for contributing immensely to informal economy and to livelihoods

of the poor and vulnerable populations(Delany & Storchi, 2012; Högman, 2009; Hulme, 2009).

The significance for adopting the concept of the informal economy as described by ILO (2002) is that

the “economic units” referred to in the description above include social enterprises, social and solidarity

institutions such as cooperatives, member organisations, and other informal entities providing products

and/or services. Community-based financial institutions fit squarely into this description of economic

units.

The South African experience demonstrates a strong bond between the informal economy and informal

financial services. The continued growth of theseinformal financial institutions demonstrates its

popularity amongst low-income earners (FinMark Trust, 2020). FinScope 2019 survey shows that

informal savings have grown from 18% in 2018 to 24% in 2019 despite high levels of financial inclusion

interventions by the South African banks (ibid). In addition, Lukhele (2018) the President of the

National StokvelAssociation of South Africa (NASASA) confirmed that there are over 11 million

members in over 800 000 Stokvels circulating over R49 Billion per annum in the South African

economy. NASASA is a self-regulatory organisation that represents the interest of Stokvels aslegislated

by the South African Reserve Bank.

Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS), Act Number 37 of 2002 requires that all

financial institutions register in order to provide financial services and Section 7(1) in particular

requires all advisors to be fully compliant in order to render financial services to the members of the

public. However, Section 7(1) and Section 44(4) of FAIS Act exempt community-based informal

financial institutions, and specifically, stokvels or savings groups and burial societies from licensing

to be able to render financial services to, or on behalf of its members in respect of its members

(Government Gazette Number 36316 of 2 April 2013, and Financial Services Board (FSB) Notice

Number 43 of 2013). Again, the Government Gazette Number 35368 of 25 May 2012, and

subsequently Government Gazette Number 37903 of 15 August 2014 of the South African Reserve

Bank, confirms that activities of Stokvels and Savings Groups do not fall within the meaning of "the

business of a bank" as pronounced in the Bank Act number 94 of 1990.

Box 2:Exemption of community-based informal financial institutions by South African legislation

Community-based informal financial institutions thrive through meaningful participation of creators of

the groups. Dlamini (2016) draws on Arnstein’s (1969) and Freire’s (1970) description of participation

– where members should have total control and continuously core-create usable knowledge during

participation. This is very important for the study because it recognises that participation is learning and

transformative.

10

In South Africa, community-based informal microfinance institutions take many formssuch as burial

societies, year-end grocery stokvels, savings and credit groups, rotational groups, investment groups

and multi-function groups. These groups either take ROCSA or ASCA methodology depending on the

goal of each individual group. The purpose of this section is to describe the most used community-

based microfinance service vehicles in South Africa.

1.1.1.Burial societies

Burial societies are group-based micro-insurance funeral providers based on the notion that neighbours,

friends, family members and relatives will experience the tragedy of death. A burial society is a local

institution and usually composed of people who know each other very well and who agree to build a

social relief fund that is used to support a bereaved family. A burial society is established by a

constitution which regulates its governance and operation. A constitution specifies rules of

participation, premium amount and benefits policies. In the event of death, benefits are paid to the

member’s family to cover some funeral costs, in some cases, all funeral costs (Dube,2016). Despite

high risk of simultaneous claims that may substantially reduce individual payments, or worse,deplete

the group’s fund, burial societies remain the most common micro-insurance service found in rural

communities.

1.1.2.Stokvels

Product-specific groups like year-end grocery stokvels are known for consumption smoothing.

Members of the group contributea fixed amount of money towards purchasing of specific consumer

goods and products at the end of each savings cycle. Besides bulk buying of groceries, it is now common

to find groups that are established to buy specific consumer products such as blankets, furniture,

appliances, house building material, etc. Looked at differently, the aim of such groups has nothing to

do with investments, but has to do with accumulation of household assets and lowering costs of buying

consumer goods.

1.1.3.Savings and credit groups

Savings and credit groups provide financial servicesto members and non-members of the groups.

Members of these groups contribute either fixedor varying amounts of money into a common pool

which is used to give short-term credit to members and non-members of the group. In some cases, these

groups are referred to as borrowing stokvels and are known for charging high interest rates especially

to non-members. At the end of the saving cycle, members receive back their contributions with interest

earned from providing loans. There are three basic approaches that are used to divide and share interest

in this category. Firstly, interest is divided equally only where members have contributed equal

investments. Secondly, where investment amounts differ, interest is distributed proportional to the

individual’s investment. Lastly, whether members have made equal or varying investments, the interest

11

generated becomes the property of the borrower. This means that members who do not take out loans

during they cycle are given back their investments without interest.

1.1.4.Investment groups

Investment groups are becoming very common amongst the working population and in particular, the

black middle class. Members pool their regular contribution to meet a specific investment purpose, for

example, to earn high interest from financial institutions or to undertake business ventures. Basically,

investment groups are established purely for investment goal that is decided by each individual group

at its establishment.

1.1.5.Multi-function groups

Multi-function groups usually emerge from strengthened social bonds and sustained operation of any

type of a group. For instance, a savings and credit group may include a funeral insurance, bulk buying

service and any other financial service in support of the founding goal.

In summary, user-operated financial institutions provide at least three financial services. Firstly, they

mobilise regular micro-savings that they use to build jointly owned loan funds or capital. Secondly,

they thenuse loan funds to provide micro-loans to borrowers, who in many instances are either creators

of a group or trusted borrowers in the village. Lastly, they dissolve group funds in order to pay lump

sums proportionally to shares owned by each creator of thegroup.

1.2.Provision methodologies of community-based microfinance services

The purpose of this section is to describe three main methodologies that are used to provide community-

based financial services in South Africa.

1.2.1.Microfinance NGOs

Microfinance NGOs, popularly known as Non-Governmental Organisation Microfinance Institutions

(NGO MFIs) are not-for-profit financial institutions. Examples of microfinance NGOs in South Africa

that provide micro-loans are Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF), Marang Financial Services and

Women’s Development Businesses Group (WDB). There are other South African microfinance NGOs

such as SaveAct that promote VSLA methodology. International microfinance NGOs include

Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) International, Opportunity International,

ACCION International, World Vision International, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), Save the Children,

Freedom from Hunger and Oxfam. The significance of microfinance NGOs is that they have extensive

experience in terms of structuring financial services and reaching excluded populations.

12

Funding for microfinance NGOs come from different sources and mainly from international donors and

in some cases, central governments. However, they are not supervised by the central banks, but are

governed by boards that are regulated by country laws (Ledgerwood, 2013). A key feature of

microfinance NGOs is their ability to generate interest from loans that they re-invest and use to finance

their operational costs and to extend their reach. Generally, microfinance NGOs use solidarity groups

to grant business loans.

The pioneer of the solidarity group model is the Grameen Bank. A solidarity group model is when

members of a savings group guarantee a loan granted to a borrower by an external lender (microfinance

NGO). In other words, the legal obligation to repay the loan becomes the responsibility of the group. In

the event that a borrower defaults on a loan, group members must settle the loan as no further loans will

be extended to the group members without settling the group loan. In this way, savings groups are used

as collateral security.

Methodological approaches and services offered by South African microfinance NGOs are summarised

below.

Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF)

Founded in 1992 and headquartered in Tzaneen in Limpopo, SEF operates in seven provinces in South

Africa. SEF provides small microenterprise loans, mainly to rural women (www.sef.co.za). By the end

of 2022, the average loan size was just over R4 300 from over 175000 active borrowers. Most funded

microenterprisesare in the trading space which includes fruit and vegetable vendors, second-hand

clothing hawkers, dressmakers and convenience shops. SEF uses the Grameen Bank solidarity group

model as collateral to loans. SEF does not provide savings groups; however, applicants formicro-loans

are required to build a group fund by operating a SA Post Office savings account where they put their

regular savings.

Phakamani Foundation

Phakamani Foundation is microfinance NGO that provides small loans to rural women to start and

operate microenterprise operations. Phakamani Foundation operates mainly in Mpumalanga, Limpopo

and KwaZulu Natal. It uses the solidarity group approach where six women undergo selection and

training before they could access a business loan (www.phakamanifoundation.org).

Marang Financial Services

The collapse of the Get-Ahead Foundation and Rural Finance Facility in 2000 saw the establishment of

Marang Financial Services. Marang Financial Services took over the infrastructure, clients and the staff

from Get-Ahead Foundation and Rural FinanceFacility. With over 23 branches, Marang Financial

Services operates in Eastern Cape, Gauteng, KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. It also

employs the Grameen Bank solidarity group model to grant microenterprise loans of up to R10 000 to

borrowers who do not have the required collateral required by formal banks.

Women’s Development Businesses Group (WDB)

Women’s Development Businesses Group (WDB) was established in 1991 and operates in the Eastern

Cape, KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. The core businessof WDB is provision of

microcredit to rural women in order to improve their livelihoods through economic empowerment.

13

There are two main categories of borrowers. WDB offers basic financial skills and credit management

training for entry-level income microenterprises. Borrowers in the category qualify for loans of between

R300 to R4 000. The second category is made up of entrepreneurs who receive more substantive

business skills training and who are assigned business mentors. This category receives loans of between

R5 000 to R10000.

Common features of microfinance NGOs

The purpose of this section to discuss the most common features of microfinance and criticism levelled

against them by some dissenting voices. The following are common features of microfinance NGOs.

•Microfinance NGOsare largely registered as not-for-profit companies or trusts. They have no

shareholder capital which makes it difficult to finance growth through commercial loans.

•They are caught between social welfare andeconomic development objectives. Many microfinance

NGOs target rural women with the aim of helping them to claw their way out of poverty.

•They use donor funds to provide loans and to finance their operations. Although they may provide

financial education and some technical development support, their principal product is credit.

•They do not provide savings products; however, they do promote group savings accounts with a

reputable bank.

•They use the Grameen Bank solidarity approach to guarantee individual loans.

Shipton (1990) notes:

“Farmers need not just credit, but more and better opportunities for savings, partly to reduce

their dependency on borrowing. A financial policy based on only credit without savings is not

only ethically dubious, but also impractical; it is like walking on one leg” (pg.2).

The impact of microfinance NGOs on the poor and vulnerable populations has been under scrutiny for

a while. While microfinance services are often seen as a positive move toward improving access to

financially excluded populations, Shipton (1990), Hulme (2003), Bond (2006), Ditcher and Happer

(2007), Harper (2010), Bateman (2011), Duvendack et. al., (2011) and Mader (2015) have beenvery

critical of the usefulness of microfinance programmes. These researchers make the following arguments

against these microfinance programmes:

•The dominant financial regime is predatory in that it traps low-income earners into consumption

and debt thereby reinforcing poverty (Bateman, 2010; Duvendack etal., 2011; Mader, 2015). Mader

(2015) argues that interest generated from microloans is living proof that the formal financial

institutions have commercialised poverty. Poor and vulnerable households participating in savings

groups across the globe saved about US$ 86.5 Billion, and were issued about US$ 100 Billion

microloans mainly by microfinance NGOs and about US$ 21.6 Billion interest was generated from

the poor Mader (2015).

•Stuart Rutherford worked with poor people in the slums ofDhaka for over 20 years. He documented

their experiences with regards to their sources of income, their relationship with money and what

their expenses were. He also conducted his research in selected settlements in South Africa,

Bangladesh and India and collected household financial transactions on a fortnightly basis for

nearly a decade. He subsequently published an essay in 2000 entitled ‘The Poor and their Money’.

Rutherford argues that poor people are risk averse, fear credit but need greater than their usual sums

of money from multiple income streams in order to meet life-cycle events (Rutherford, 2000).

14

•Bond (2006) and Gleason (2013) argue that microfinance institutions tend to extend small loans to

the poor at very high interest rates, in an attempt to recover costs of lending and to achieve

profitability.

•Poor people qualify for small loans for businesses. Poor people do not take loans that risk their

livelihoods hence they tend to take conservative loans that they are able to repay (Karnani, 2006).

As a direct consequence, small loans flood the local market, create competition and make it

impossible for borrowers to make any substantial profits from their enterprises and in particular,

from agriculture (Bond, 2006; Karnani, 2006).

However, there arefew NGOs that have provided intermediary financial services. Lima Rural

Development Foundation (www.lima.org.za) is non-profit organisation that has piloted a revolving

credit facility for smallholder farmers though the Jobs Fund (www.jobsfund.org.za). The Jobs is the

South African Treasury initiative that co-finances projects that significantly contribute to job creation.

This funding is open toNGOs, businesses and government organisations. Farmers apply for the loan

which is needed, through a formal application process. The loan is then assessed by a credit committee.

A repayment plan is created and issued to the farmers. The approved loans arethen granted, through

the purchasing of actual inputs required by that farmer. There is no handing-over of cash. Average loan

size is R10000 and all loans are interest free.

Payments are made according to repayment schedule and usually soon after a farmer has sold his or her

produce. Although the revolving credit fund has been successful, some challenges associated with crop

failure and market complications. The main weakness regarding the provision of financial services by

an NGO that is not a MFI is that it does not have the instruments and capacity to manage its revolving

credit facility. It can be argued that the true cost of providing a loan is not known. The cost of providing

these loans is likely to be very high. This is because loan application processes through to approval and

recovery is hidden the salaries of the field staff.

1.2.2.ROSCAs

ROSCAs are also known as “merry-go-rounds” or “self-help groups (Samer, 2015; Wrenn, 2007).

These are arguably the oldest and most common practice for mobilising money. Basically, members of

the group agree to make regular cyclical contributions to a group, which is then given as a lump sum to

one member of the group in a given meeting. Once all members have had a turn to receive their lump

sums, the group closes the cycle and starts afresh with old members or a combination of new and old

(Duvendack et al., 2011). This method is simple. Safe keeping of the group fund is not required. All

members’ contributions go straight to borrowers. There is no interest involved on loan repayments.

Record keeping is minimal.

1.2.3.ASCAs

Generally, in ASCAs members save regularly and usuallyon monthly basis in the case of South Africa.

Members of the group pool their savings in order to build a group fundthat is used to provide microloans

to members. Borrowing is not compulsory. Loans are issued to members who need the loans. The rest

15

of the members must be confident that borrowers will repay the loans in accordance to the rules of the

group. The VSLAs fall into this category and is discussed in details in the next section.

1.2.4.VSLAs

Members of VSLAs pool regular savingsthat build what is known as group funds. Members of the

group establish a share price and interest rate at the start of a savings cycle. A savings cycle is a measure

of time (usually weeks or months), which a group takes to execute and complete its business.

A share price is the amount of money that members agree to pay each time they meet. A share price

and maximum number of shares that a member can buy in a meeting are decided at the establishment

of the group. Generally, the VSLA model allows members to purchase between 1 and 5 shares in a

meeting. There are groups that allow members to purchase up to 10 shares in a meeting.

The share price is set low enough to ensure that every member canpurchase at least a share in every

meeting. For example,if a share price isR100, a member can save between R100 and R500 in a meeting.

Group funds are used to give micro-loans to internal borrowers. All interest payments are added to the

group fund. Borrowing by non-membersof the group is not allowed. At the end of the cycle all the

money in the group fund which is made ofsavings, interest and fines are paid out the members

proportional to the deposits (savings) of individual members. Further operating procedures are

presented as annexure of this report.

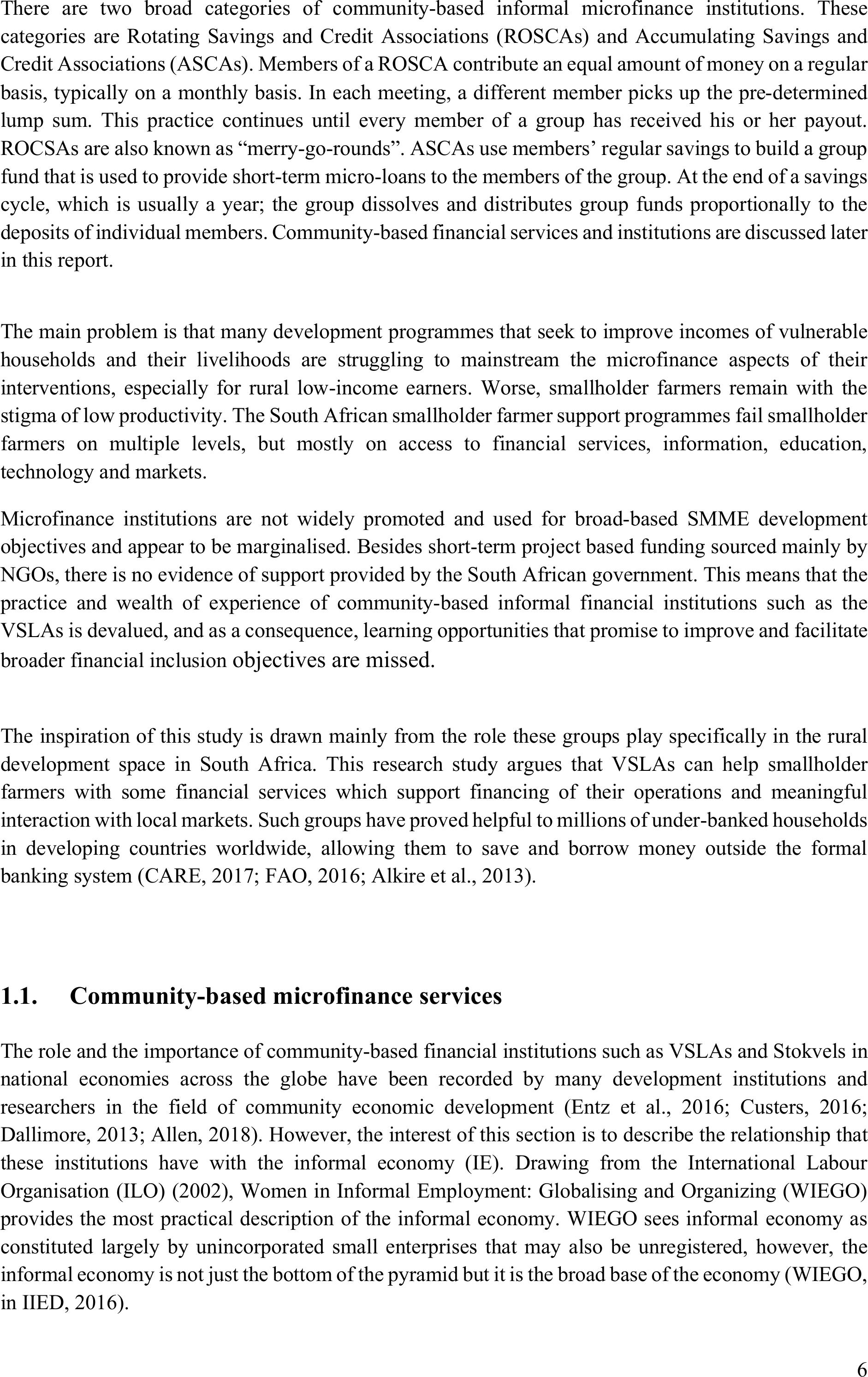

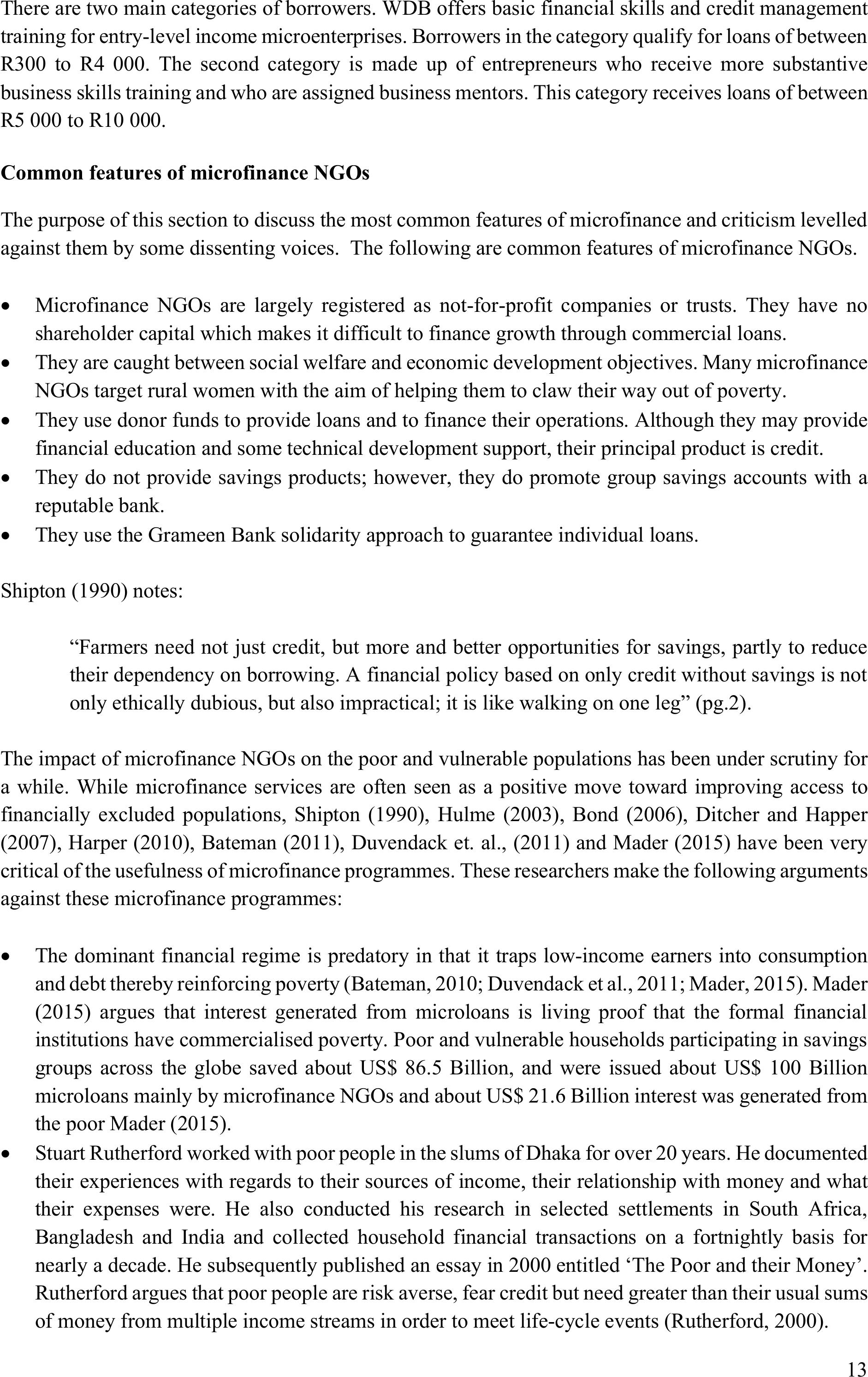

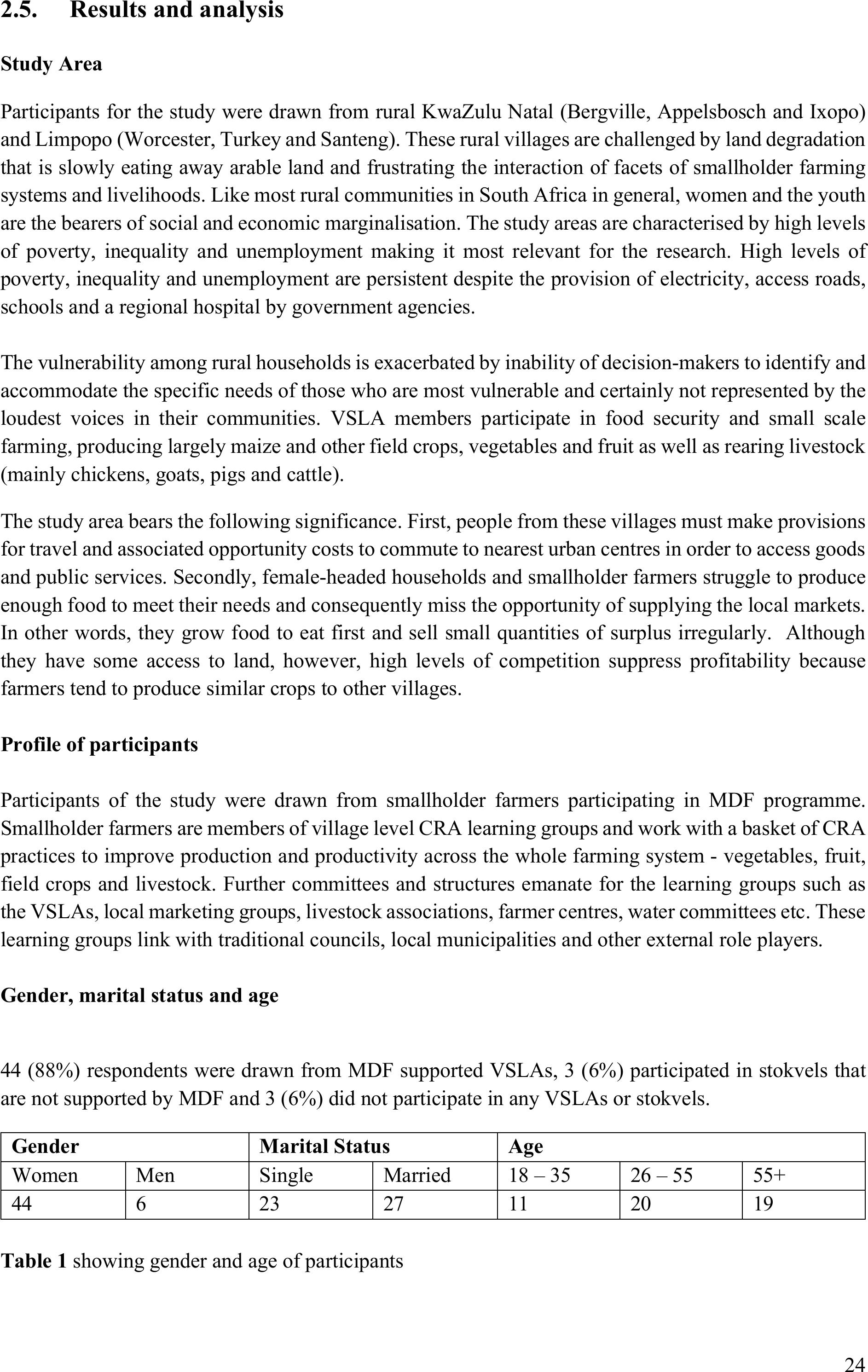

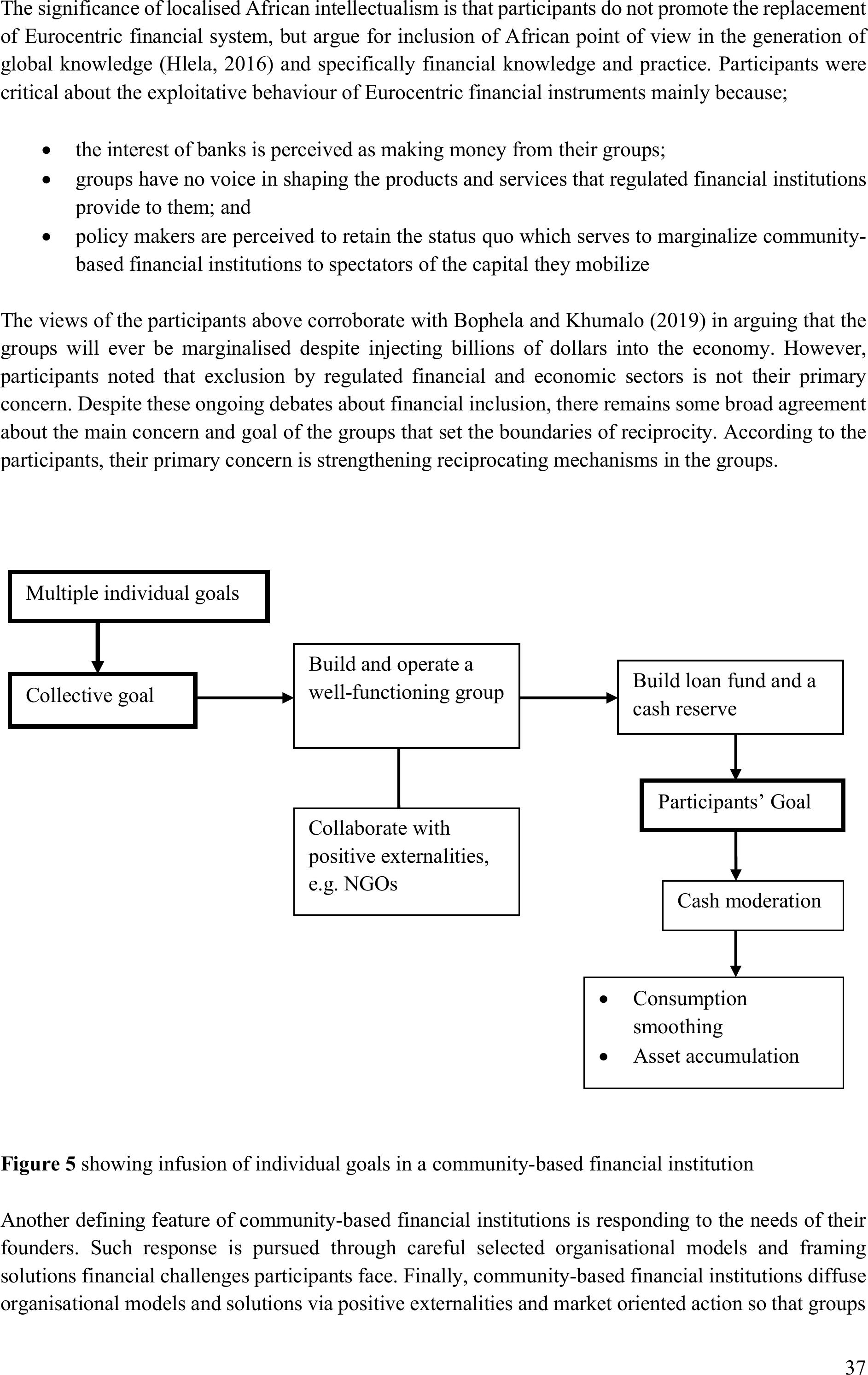

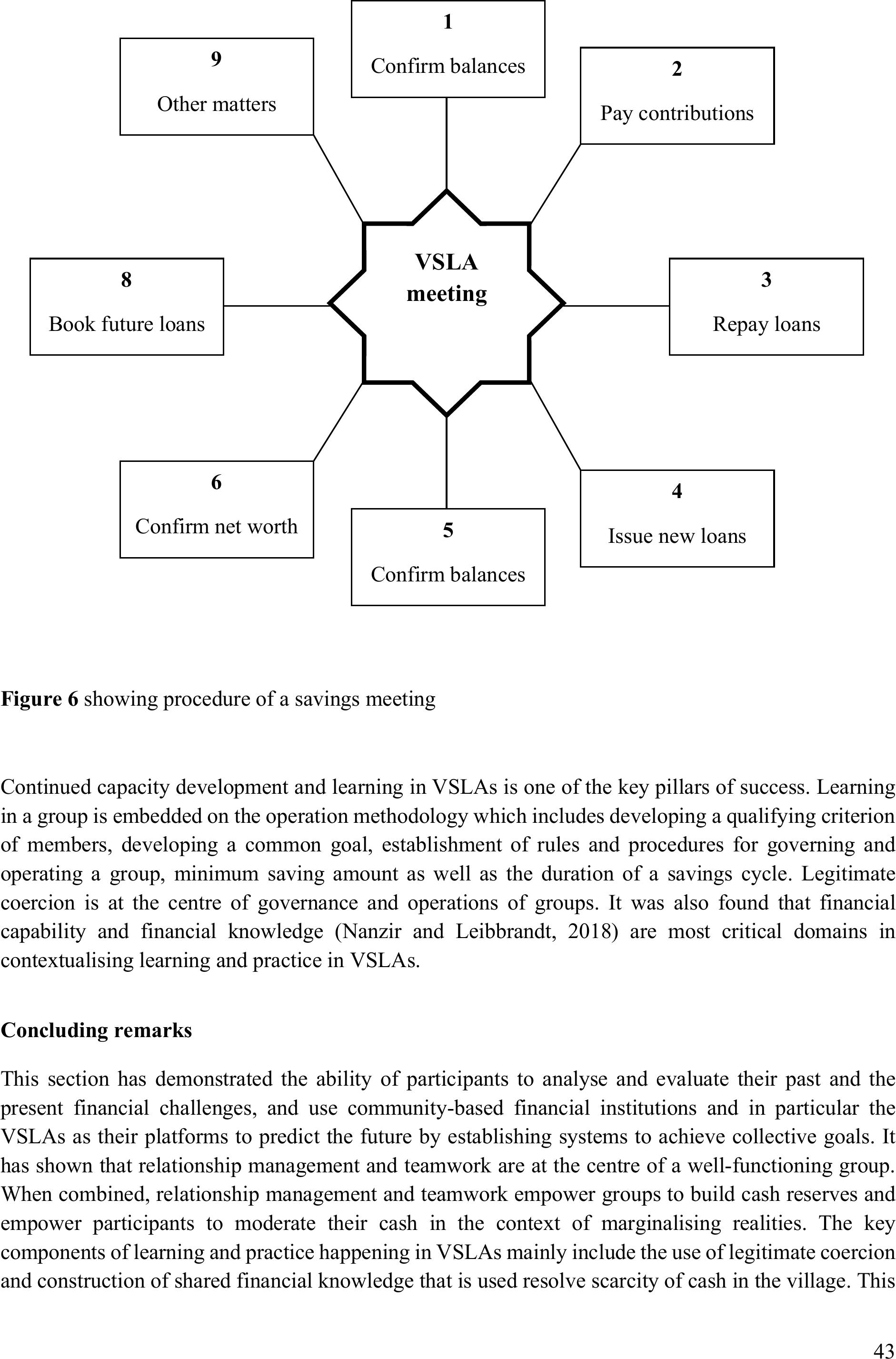

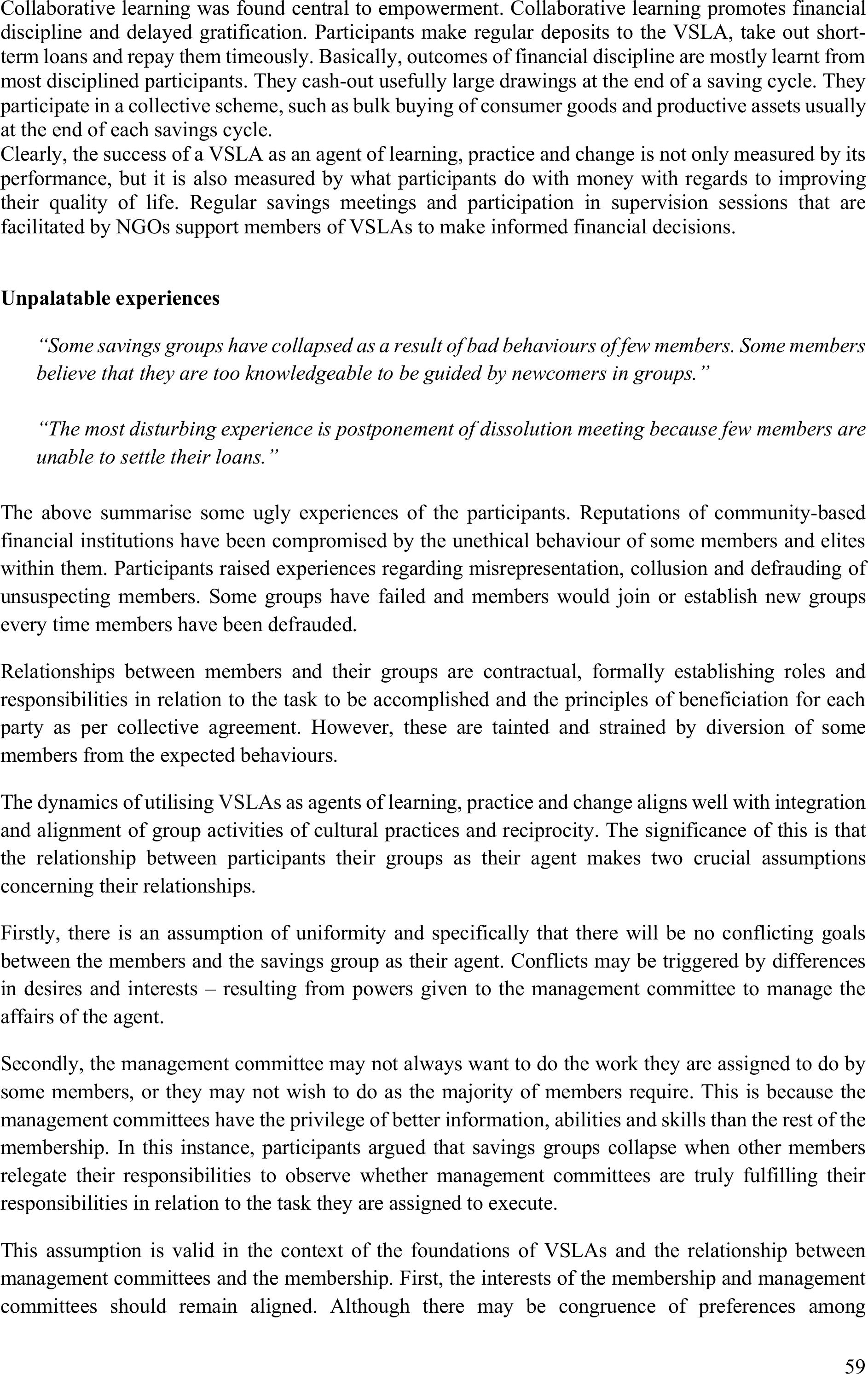

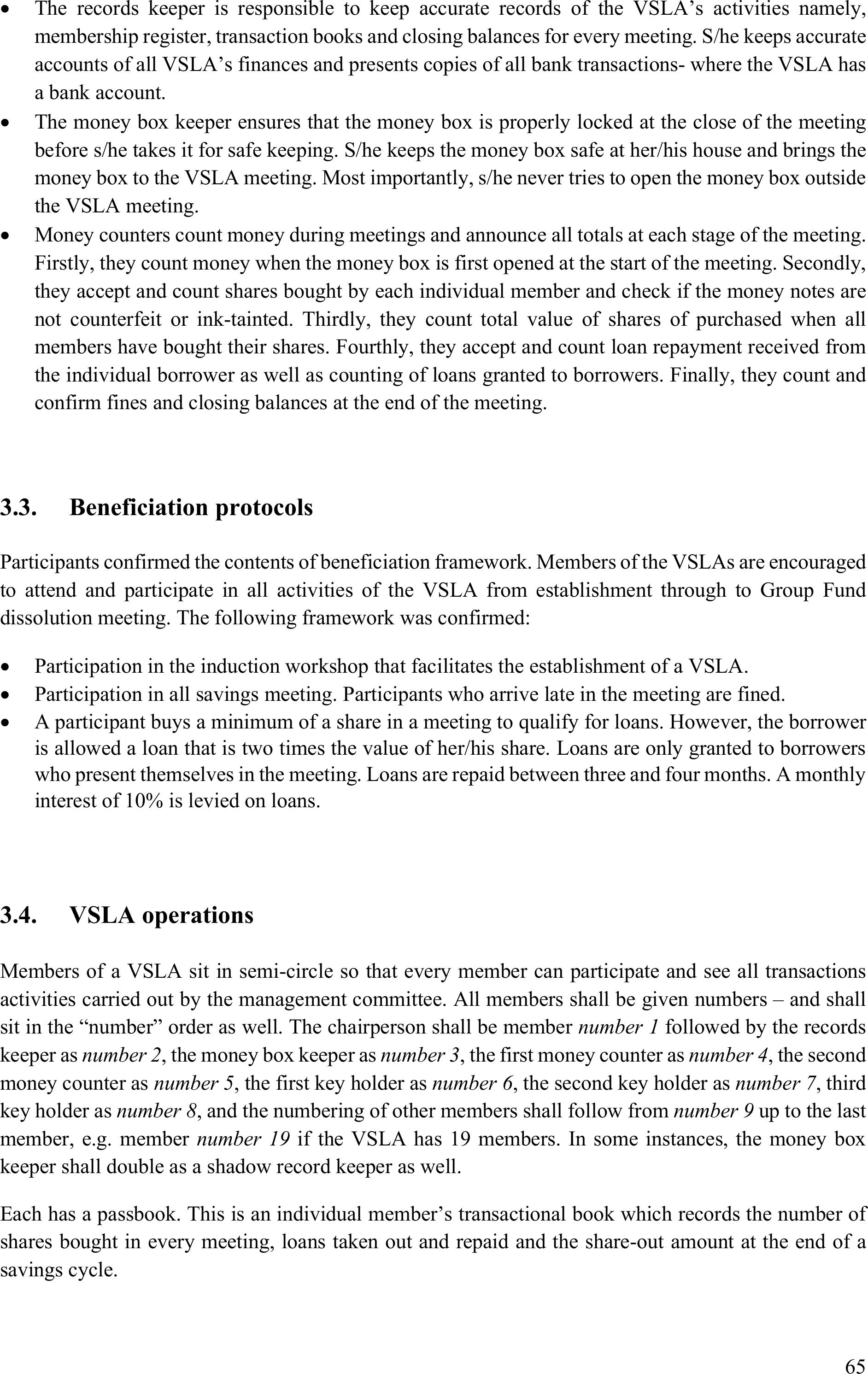

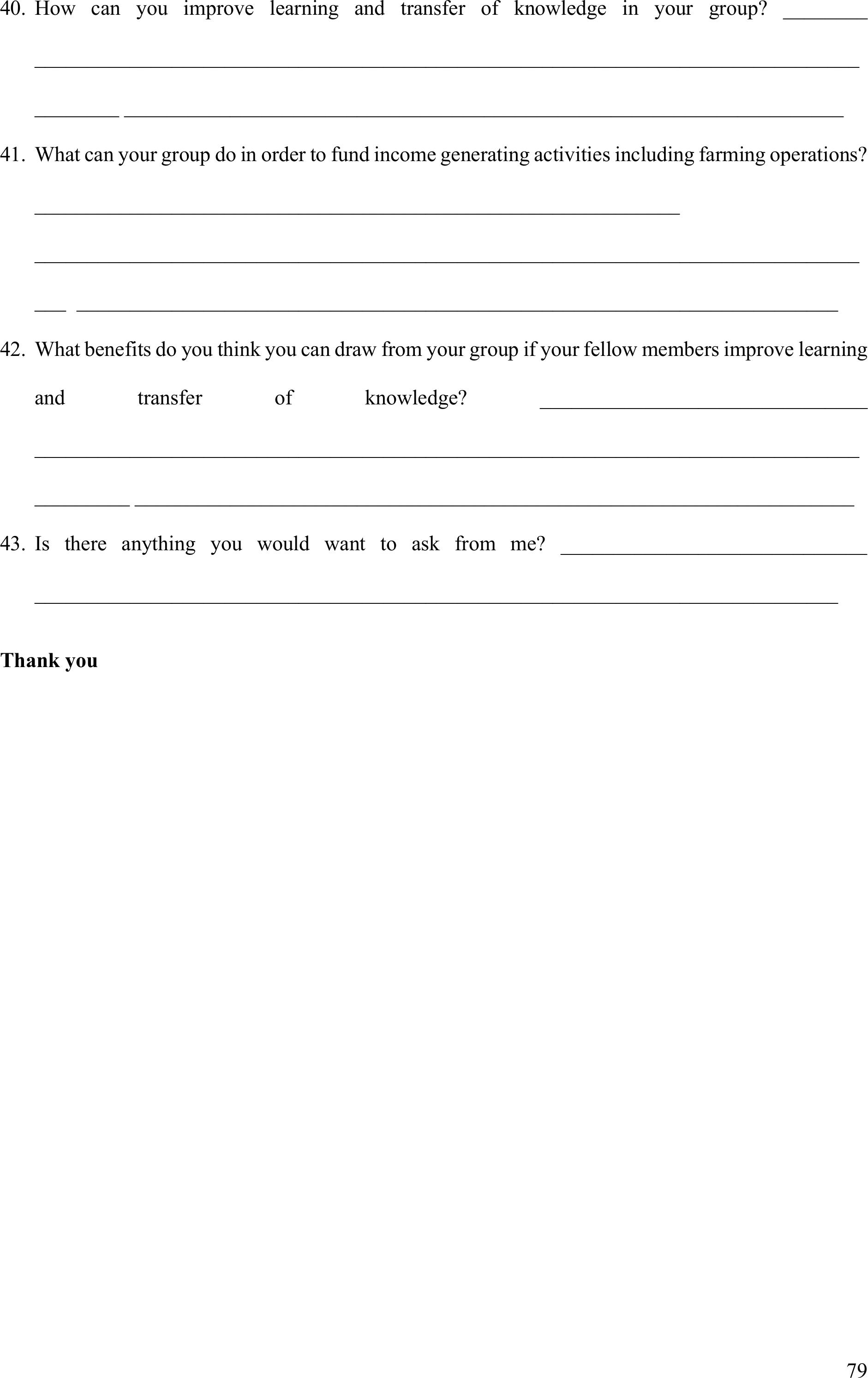

Figure 2showing the structured approach to VSLA development, adapted from Hugh Allen (2021)

Establishment

phase

Community

sensitisation

meetings

VSLA establishment

Training and VSLA

formalisation

Supervision

phase

Recruitment

Monthly

supervision and

re-training

Graduation

VSLA

performance

evaluation

Post supervision

phase

16

MDF uses the VSLA model. Themodel is savings-led and is designed to empower poor households to

build up assets and to achieve levels of financial stability better than credit-led programmes (Dlamini,

2016 citing Delany & Storchi, 2012). There is anorganised and accountable system or structure of

conducting group meetings and recording of transactions that is largely trusted by every member (ibid).

MDF chose the VSLA model because groups save and then lend out the accumulated savings (group

fund) to others without seeking externallyprovided micro-loans. Interest generated stays with the group

and is not siphoned out byanexternal loan provider. In this way, members of the groups are not exposed

totherisks and complexities associated with external loans.

VSLAs can be establishedanytime during the year but set a firm time period after which they will

distribute the group fund. Figure 2 shows the 4 main phases in the first year of a VSLA. At the start of

the programme, VLSAs are trained by field staff, that is, programme facilitators who are employed by

MDF. Programme facilitators usually dedicate between 3 and 4 weeks for recruitment, establishment,

and initial training of VSLAs. Programme facilitators are notallowed to manage VSLAs on behalf of

its members. This includes writing and keeping records, counting money and safe-keeping money box.

These functions are always carried out by the members of the VSLA.

1.3.Making connections

The purpose of this section is to show the connections between smallholder farmer-focused VLSAs and

the CbCCA that is implemented by MDFas well as African cultural practices in the context of

community development. CbCCA is inclusive of CRA, community-based water management to

improve access, food systems, environmental rehabilitation and conservation management, livestock

management, community infrastructure enhancement and local economic development. MDF operates

in the pro-poor agricultural innovation space. Since its inception in 2003 and focussing on agro-

ecological approaches, MDF has worked in the field of integrated agricultural development in selected

communities in KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces of South Africa. Its head office

is located in Pietermaritzburg in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

MDF collaborates with other non-profit organisations to design and implement food and nutrition

security programmes that are aligned to sustainable livelihoods and an agricultural innovation agenda

that is underpinned by strong community partnerships, participatory researchand learning.

The vision is to support the harmonious living of people in their natural, social and economic

environments in ways that supportand strengthen the ruralpoor to better their lives, to diversify their

livelihoods and to face their challenges with resilience. MDF believes that in this way vulnerable rural

populations will be able to live harmoniously with their immediate environment while improving their

sources of income and consequently their quality of life. This vision aligns perfectly with MDF’s

mission that seeks to keep MDF at the cutting edge of development methodology and processes by

integrating social learning, participatory action research, on-the ground training and supervision of

implementation solutions with participating communities.

Broadly, MDF’s development programmes integrate sustainable natural resource management,

intensive homestead food production that is informed by Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRA), low

external input farming systems, rain water harvesting, and integration of VSLAs and entrepreneurship

education in food production. The significance of VSLAs is two-fold. Firstly, they provide for

17

consumption smoothing and secondly, they provide access to finances for agricultural production and

small businesses. Community-based farmer centres allow for the timely availability of agricultural

inputs in smaller quantities at affordable prices at a village or across neighbouring villages.

MDF has adapted VSLAs to help achieve the objectives of CbCCA. CRA aims to improve yields while

rehabilitating and conserving the environment, i.e. soil and water resources. VSLAs improve access to

flexible financial services in a village through short-term loans and group fund share-out lump sums

which farmers use for: consumption smoothing, production of nutritious food, investment in farming;

establishment of micro-enterprises and other income generating activities.

This methodologypresents incentives and tangible rewards which encourage participation of the

farmers in the CRA programme. In other words, it presents a structured process to help the members of

the VSLA to achieve tangible rewards which includes achieving group goals of providing a financial

services vehicle to take deposits and to provide short-term loans to members for production purposes.

In the contextof African traditional practices, culture would refer to the totality of the pattern of

behaviour and the primacy of philosophical beliefs,taboos, social norms and practices of a distinct

group of people (Aziza, 2001). A value has something to do with a very strong conviction or worldview

that permeates every aspect of human life (Idang, 2015). Igboin (2011) maintains that certain cultural

values consistently define the African personality despite damage caused by colonialism. In the context

of development, Idang (2015) argues that cultural and economic values of traditional African societies

promoted cooperation, for example, friends, relatives, neighbours would help one another in performing

laborious production chores like farming and house construction. The practice of savings groups is a

microcosm oftheAfrican way of life because it provides support to members of the groups (Oduyoye

1997) and strengthens communal living which disallows the vulnerable to perpetually struggle in

poverty (Moyo 1999). The significance of Zulu cultural and economic values forthis study isthe

tradition of ukwenana, ukusisa and ilimo.

•Ukwenana is a form of exchange of property where the recipient would reciprocate

•Ukusisa is another form of exchangeof property. In many instances, the property would be

livestock and in particular heifers. The giver presents the gift knowing that the recipient would

keep the offspring as his property when returning the cow. In other words, the recipient takes

the gift knowing that he will eventually return the exact cows to the giver.

•With regards to ilimo, the initiator is the recipient. She or he will prepare food and drinkand

invite people to help with planting preparations and/or harvesting. On top of food and drinks,

the helpers would receive a small portion of what was harvested and the saying in isiZulu goes:

“umvunisi ubuya nenjobo”. The recipient would reciprocate the same to others.

In all instances, the givers and recipients are equals during and post the transaction. All three practices

are mechanism of building reciprocating social economy on the foundations of reciprocity and social

justice.

1.3.1.International best practice

From Niger in 1991, CARE-Int haspromoted the VSLA modelin 54 countries across the globe with

13.7 million(www.care.org). Many international NGOs such as CARE,World Vision, Oxfamand

Catholic Relief Services (CRS)mainstream VSLAs to support their development programmes in areas

18

of education, reproductive health, water, sanitation,food securityand nutrition, smallholder farmer

development, woman economic empowerment, gender-based violenceand enterprise development.

A VSLA is described as a community-based informal financial institution, whose founders (members)

areself-selected and agree to save regular amounts of money to build a Group Fund. VSLAsare self-

managed groups of people who meet regularly to save their money in a safe space, access small loans,

and obtain emergency insuranceknown as a Social Fund.VSLAs allow members to save flexibly,

access small loans forinvestment and build a Social Fund in order to strengthen their resilience to

external shocks such as illness, crop failure, droughts, disasters and so forth. VSLAs have been used to

address a number of challenges communities face.They have been used to;

•help household deal with irregular household incomes

•improvecash circulation in villages

•improve access to financial services

•promote income generation projects

•build resilient to economic shocks and emergencies

Groups meet on regular basis which can be weekly, bi-weekly or monthly for the duration of a savings

cycle.Basically, an association builds a Group Fund, provides interest-bearing short-term micro-loans

and distributes Group Funds proportionally to individual members’ savings at the end a saving cycle.

At the end of the cycle all the money in the Group Fund (savings, interest and fines) are paid out the

members proportional to their savings. A Group Fund is also known as a Loan Fund.

Well-functioning and successful associations must demonstrate shared goals, democratic governance

principles, full and inclusive participation, transparency, and accurate record keeping. This means that

each association must develop its constitution which makes clear pronouncements in terms of

governance and operations. VSLAs are often supported by external development agencies especially in

their first year of operation. Development agencies employ Field Officers who mobilize communities,

recruit members, train and supervise associations from establishment through to maturity.

1.3.2.South African practice

In South Africa the informal savings and credit groups are popularly known asstokvels which is

inclusive of supervised and unsupervised groups. According to FinMark Trust (FMT),there are limited

organisations that have adopted VSLA model (www.finmark.org.za).FMT is an independent Southern

African financialservices research and policy advocacy group that is focused on financial inclusion.

Founded in 2005, SaveAct Trust is one of the key promoters of VSLA model. Besides MDF, other

organisations that implement VSLAs includeFarmer Support Group (FSG) at the University of

KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Africa Co-operative Action Trust (ACAT),andZimele Developing

Community Self-Reliance (Zimele).

19

Pictures showing members of savings groups conducting their meetings

The common goal of all these organisations is supporting communities to improve their sources of

income and ultimately their livelihoods by mainstreaming VSLAs in their development programmes.

Through partnering with other NGOs, SaveAct has reached just over 105000 members in VSLAs

across 6 provinces in South Africa (www.saveact.org.za).

The South African version of VSLA involves the promotion of savings clubs, along similar lines to

those of stokvels. Members save and deposit on monthlybasis, and then on-lend to members of their

groups according to agreed terms for a defined purpose. Interest on the loans is charged, and so

members are ableto grow their savings. Members the groups are provided with VSLA training when

they start and followed by life skills, enterprise developmentand technical skills such as croppingand

broiler production.

The reasons for opting for the VSLA by South African NGOsare as follows:

•VSLA model builds on stokvel experience, indigenous knowledge and culture and is widely

accepted by communities.

•VSLA is savings-led. No money is lent by the development agency to the participating groups.

There is little financial risk involved.

•Capital growth is structured so that funds circulate amongst the members and within the

communities, rather than being absorbed by microfinance NGOs and credit providers.

•Lastly, the VSLA model readily accommodates and catalyses a wide range of livelihoods

strategies. VSLAs transform into platforms of community action. They become ‘the glue’ that

moulds and holds these groups together, and provides the platform for addressing a range of

issues., including: food and nutrition security, access to communal resources such as water,

natural resources and pastures, income generation, asset accumulation, purchasing agricultural

inputs, etc.

20

2.Study Aims and Objectives

This study aimed to examine microfinance options which are available for smallholder farmers

participating in the Community-based Climate Change Adaptation (CbCCA) and to draw lessons for

broader applications. The practices of VSLAs and other similar community-based informal financial

institutions were examined for the purposes of suggesting best practise options in microfinance for

smallholder farmers in South Africa. The study had the following objectives and key research questions.

Objectives

•To understand learnings and practices of rural communities resulting from participating in VSLAs.

•To examine the impact of VSLAs on participants’ financial behaviours andlivelihoodscompared

to stokvels or other microfinance services available in rural communities.

•To explore microfinance optionsVSLAs provide tosmallholder farmers.

Key research questions

•How internal and externalperceptions influence the operation of VSLAs?

•To what extent do practices in VSLAscontribute to better livelihoods?

•Which collaborative learning competencies describe VSLAsas agents oflearning, practice and

change?

•What is the significance of VSLAs, and what microfinance options do VSLAs provide to

smallholder farmers?

2.1.Research methodology

This study was located within the interpretivist paradigm.It sought a deeper understanding of the

significance of community-based informal financial services as one of the microfinance options

available to smallholder farmers and related village-based microenterprises. The purpose of this

interpretive research was to develop a deep understanding and insights members of community-based

informal financial institutionshave tomake sense of the context in which they live and work (Bertram

and Christiansen, 2010); and to discover the problems and opportunities that exist within these groups.

The studyemployedHuman-Centred Design (HCD). As an adaptive planning tool, HCD was used in

the study toexaminedifferent group-based financial services, identify challenges and dissect

microfinance options that are available to smallholder farmers. The significance of HCD is its ability to

transform participants into active designers of solutions for problems they face.

Essentially, HCD provides an alternative lens to understand the relationship between people and their

development. The founder of HCD, Don Norman (2022), presents the hierarchy of at least four

principles that should guide adaptive planning and community-based planning tools like HCD.

21

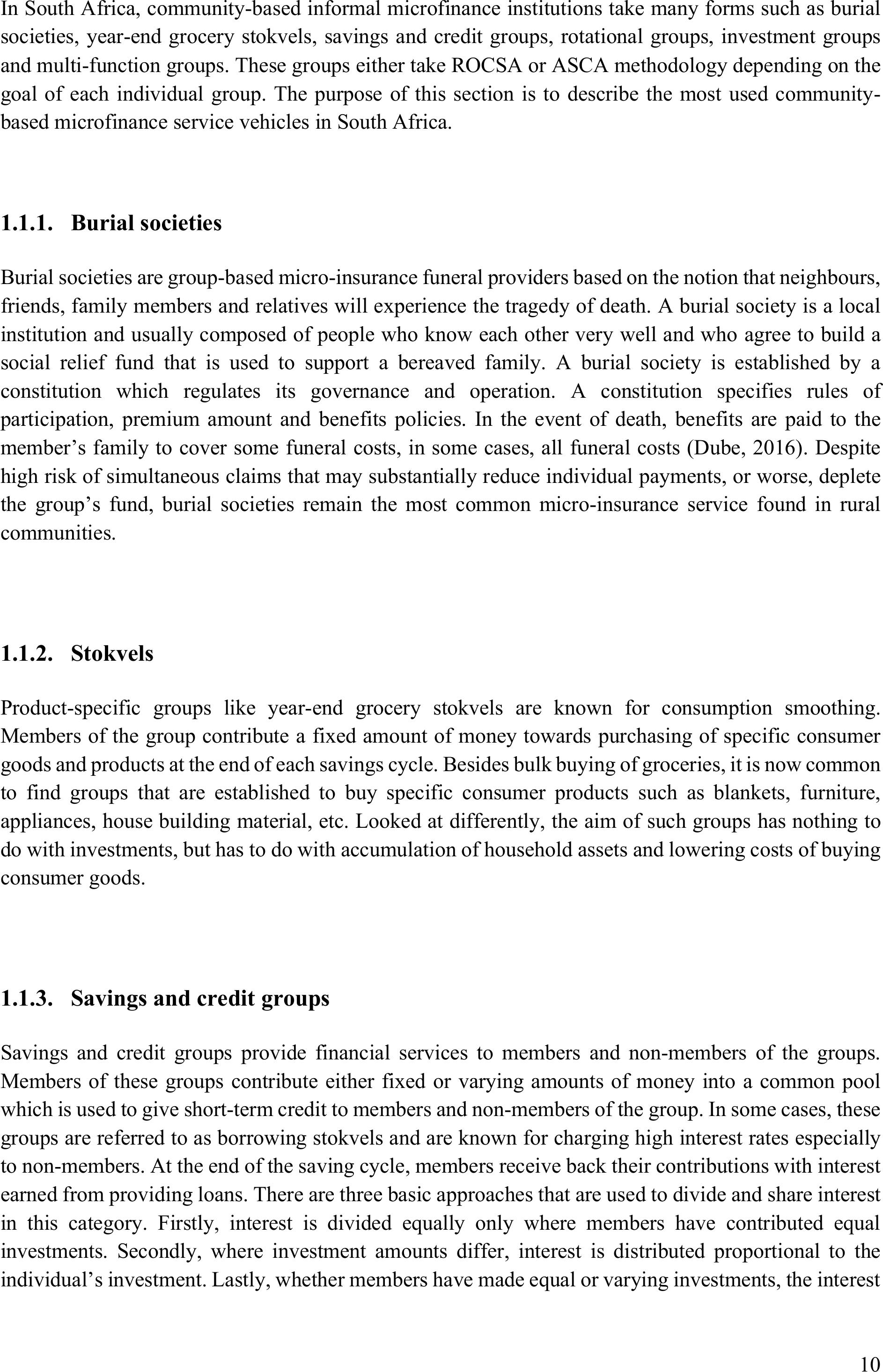

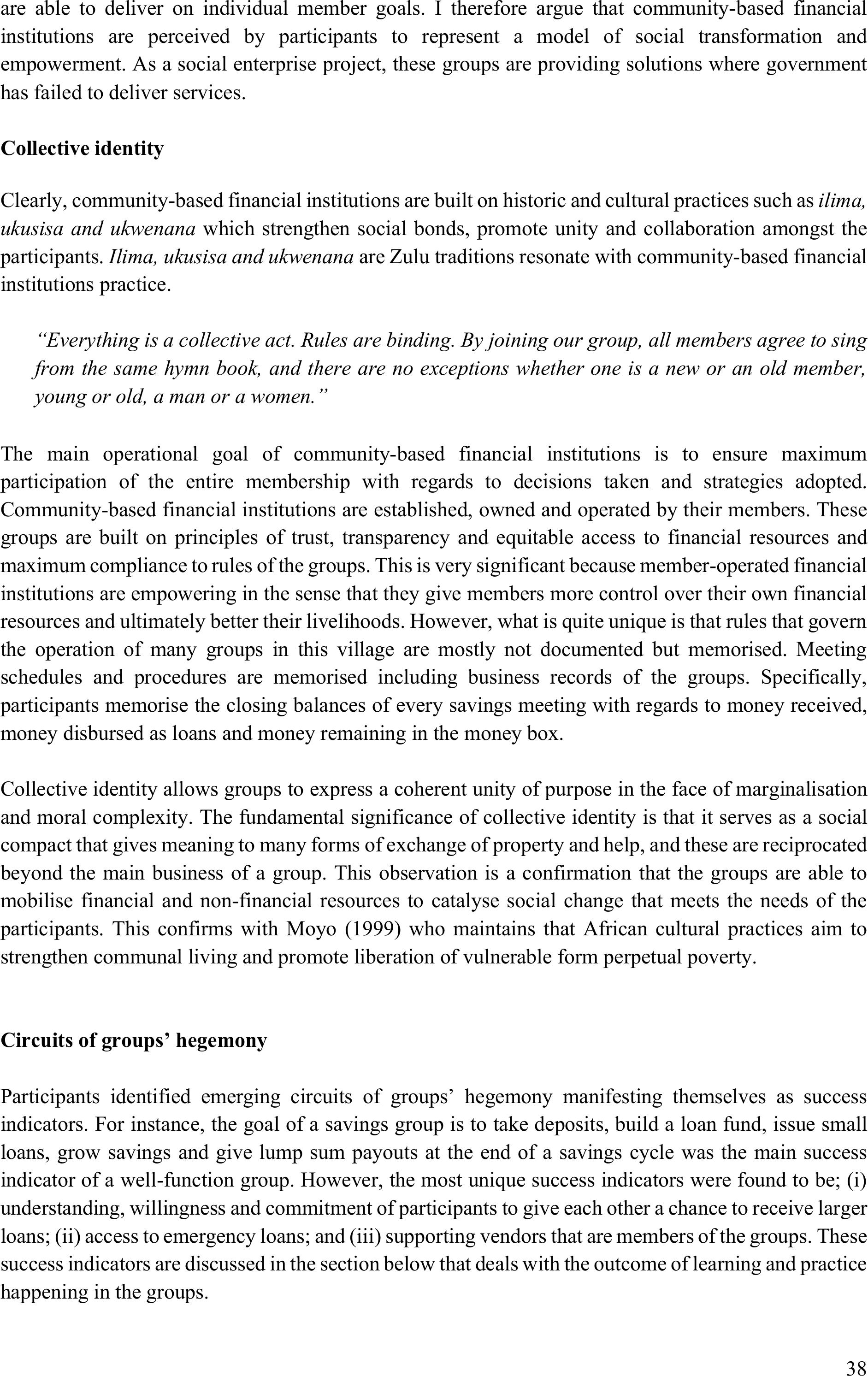

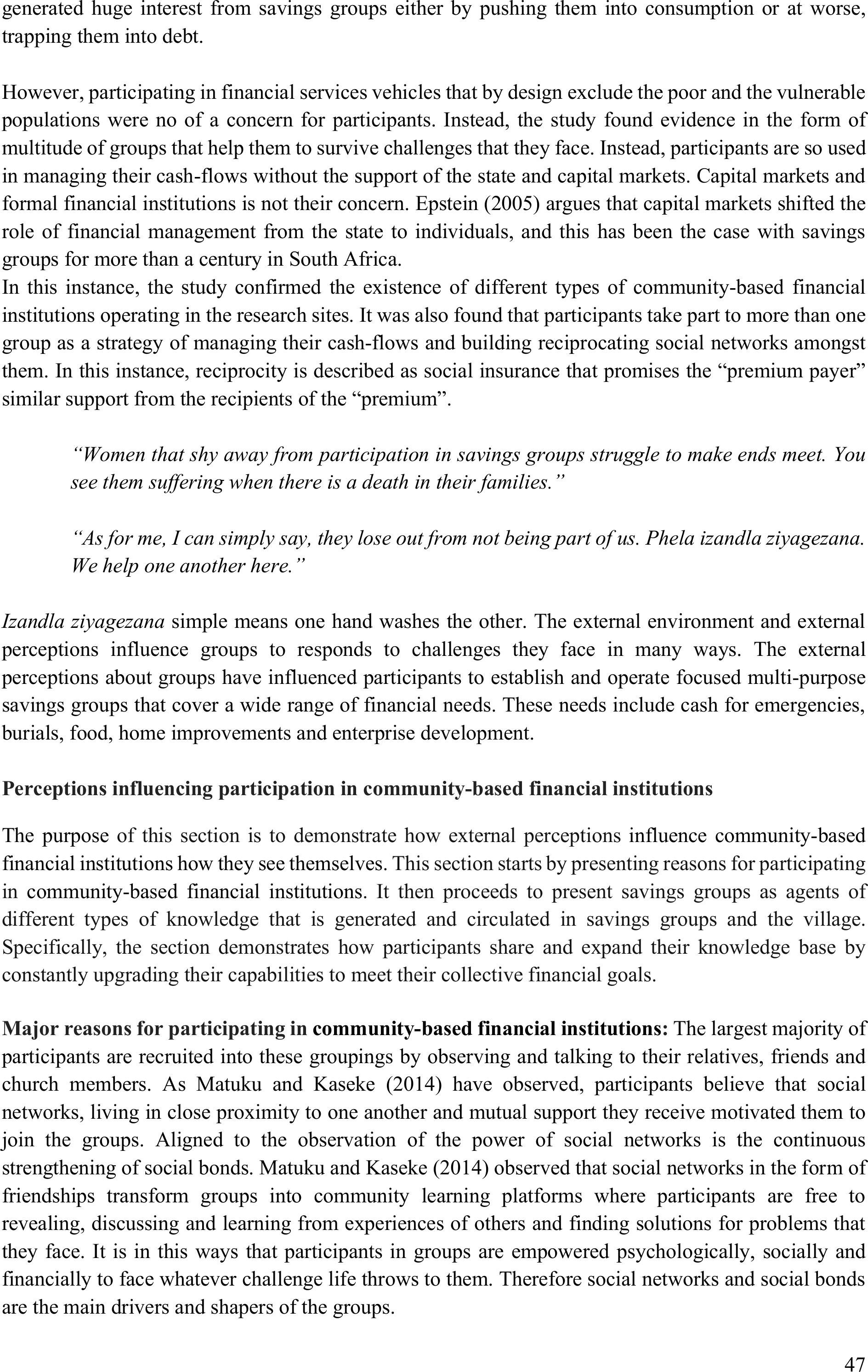

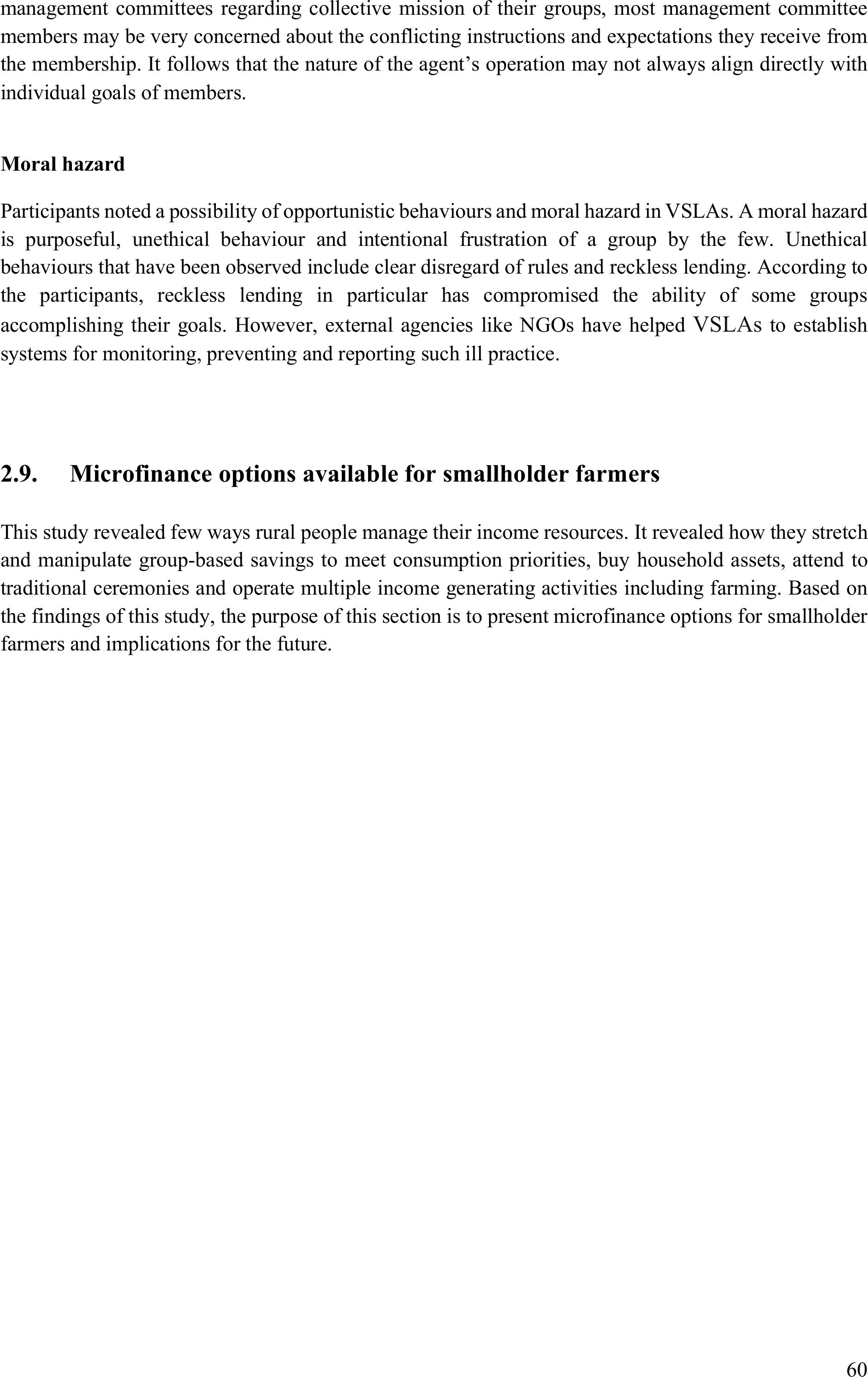

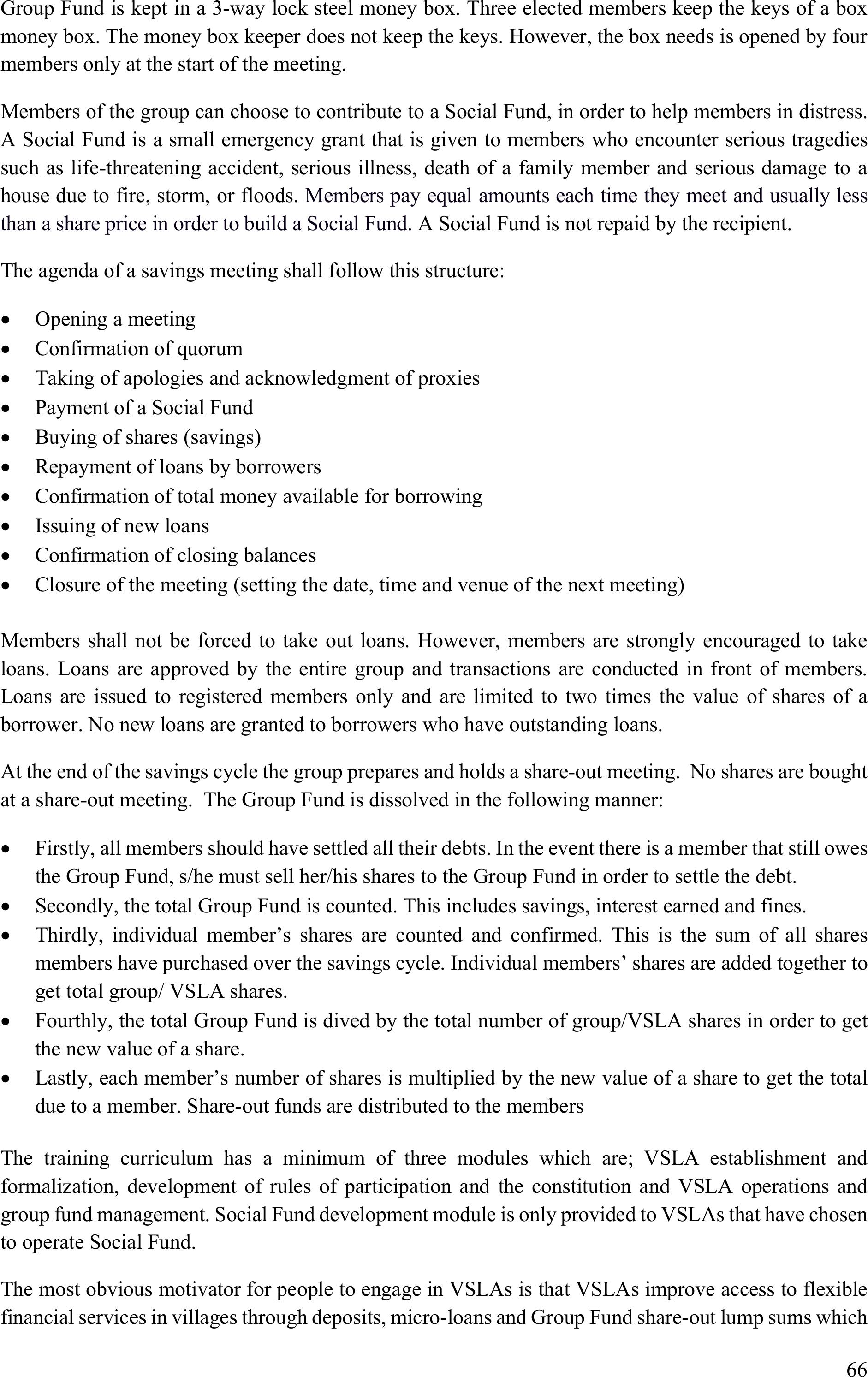

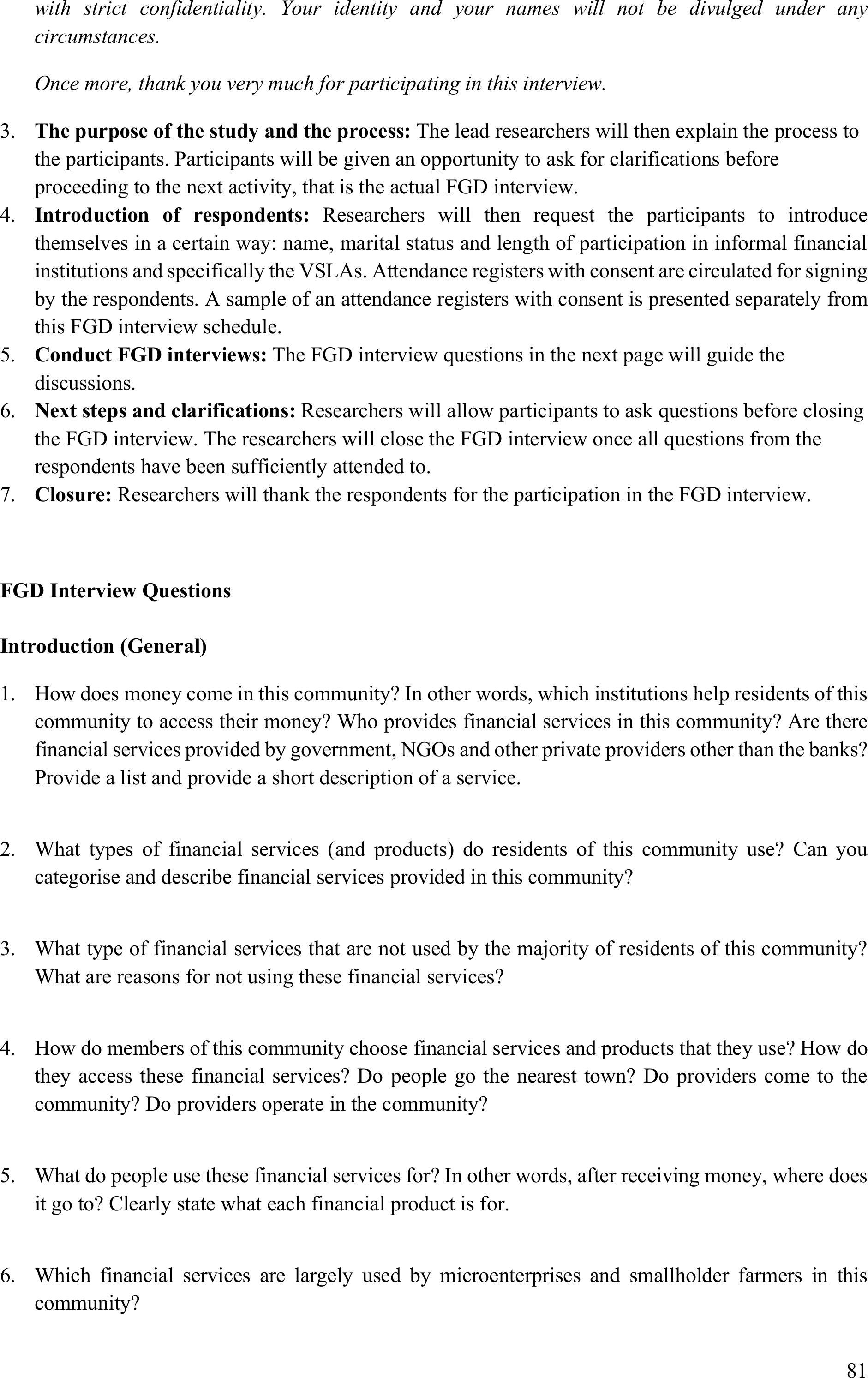

Figure 3 showing four principles of HCD adapted from Norman (2022)

Based on the above four principles of HCD, it is clear that microfinance institutions are working within

complex socio-economic systems with problems that go beyond the scarcity of cash in rural villages.

For instance, communities are isolated from areas of employment and development. Households resort

to unhealthy behaviours like alcohol and substance abuse, gender-based violence and eating

inappropriate food hence many households are unable to afford nutritious food.

There are at least five stages that are involved in the application of HCD as shown by figure 3 below.

People

Principle 1: Total focus on people who are looking for solutions

to their problems

Problem

System

Iterating

Principle 2: Always finding the right problem and not the

symptoms of the problem

Principle 3: Think of everything as a system because everything

is connected

Principle 4: Iterating and continuous improvement of solutions

designed and used by people

22

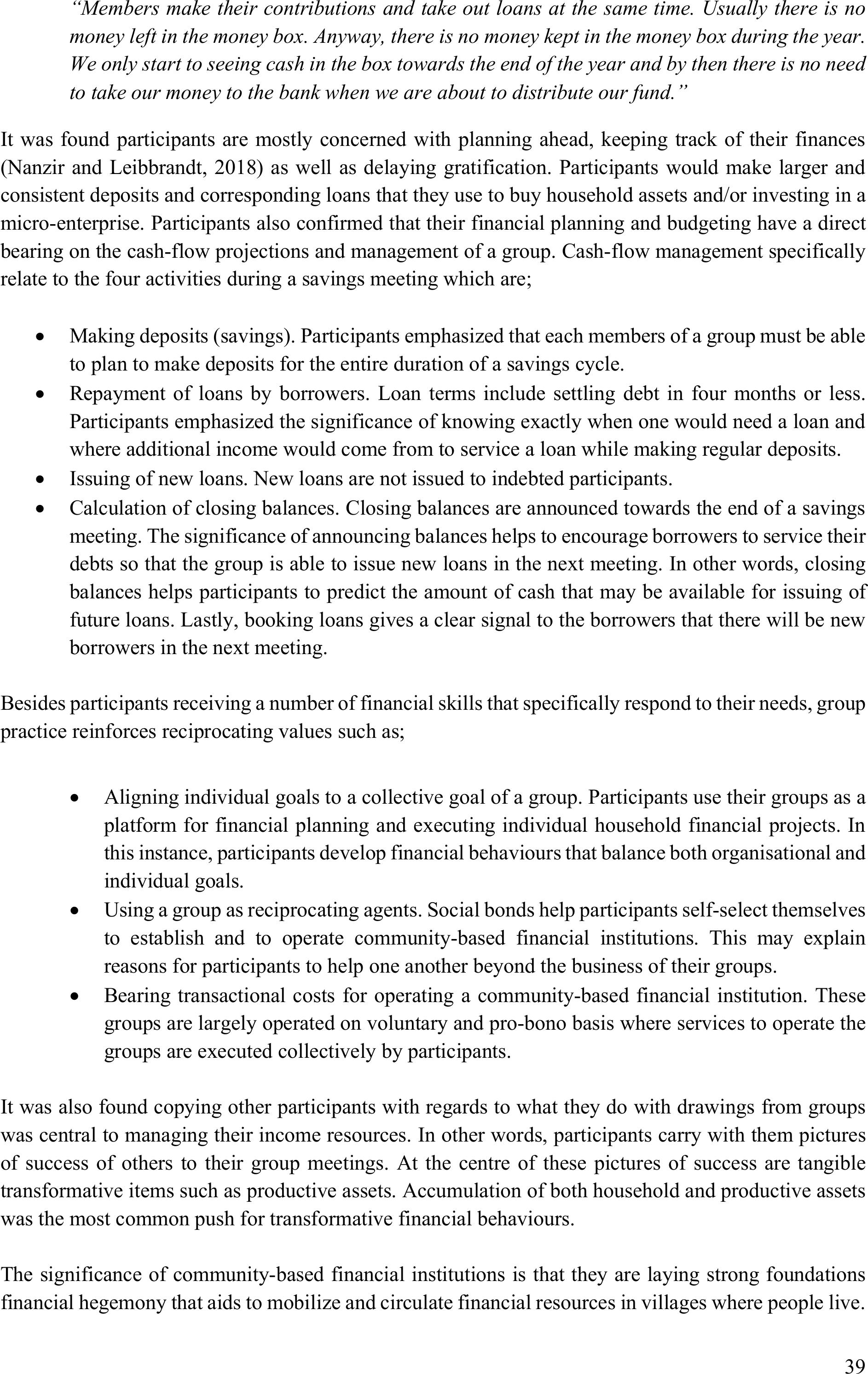

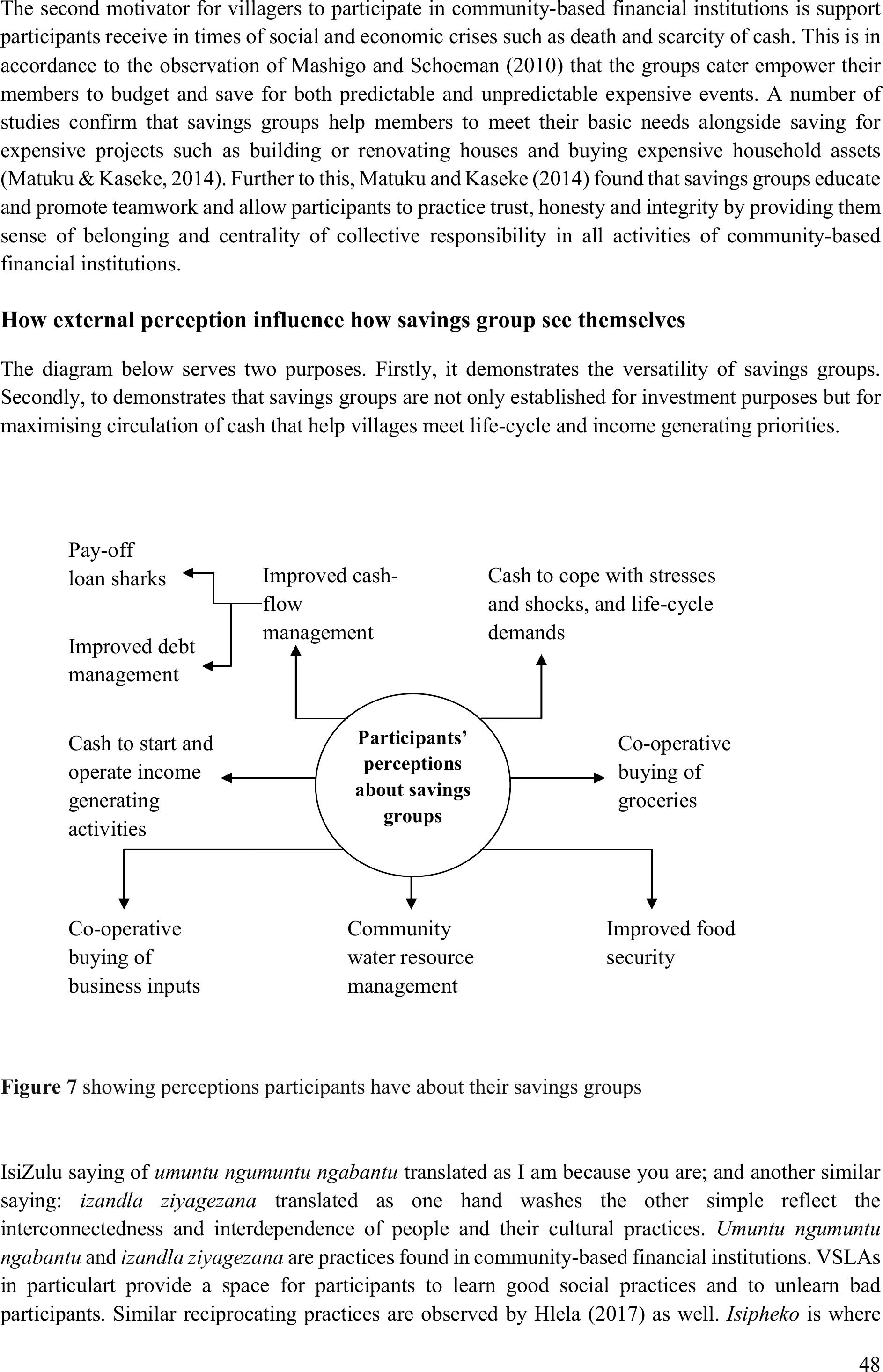

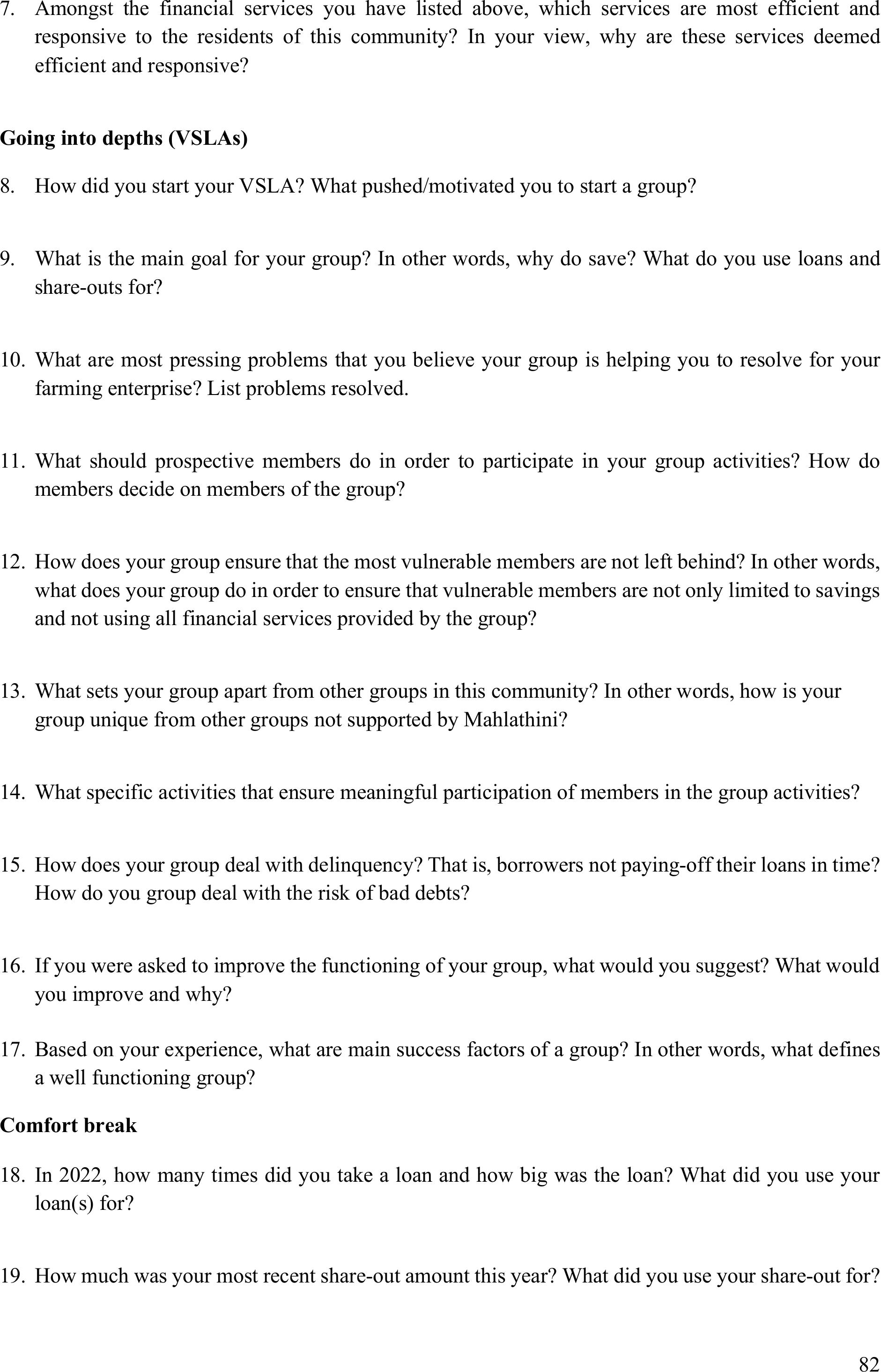

Figure 4showing five stages of the application of HCD, adapted from Norman (2022)

2.2.Sampling

Purposive sampling was applied in this study. The decision to employ purposive sampling was

influenced by the aim of the study, the anticipated role of the respondents and having prior insights

(Leedy and Ormrod, 2010) about the VSLA programme. The sample was made up of people who

participate in development programmes that are implemented by MDF, and in particular,farmer

learning groups and VSLAs. Stokvel participants were interviewed asa control as they were not

Empathise

Define

Ideate

Prototype

Test

This stage describes

people that are facing a

problem. For instance,

this phase describes

where people live, what

they do, how they earn

their living, etc.

This stage identifies,

describes and prioritises

the problems and needs

the targeted people. It also

explores and draws in the

capacities, experiences

and insights the targeted

people already have that

can be used in designing

solutions to their

problems.

The focus of this stage

is development of ideas

and potential matches

and prioritisation of

ideas that promise

solutions.

This stage transforms

ideas into simple

testable solutions (or

prototypes).

This is the final stage. It

tests prototypes. Iteration

and continuous

improvement dominate

this stage. However, if

the outcomes of the tests

fail to resolve the

problems people face,

designers may revert to

earlier stages until a

solutions if found.

23

members of the VSLAs. Participants in the study live in rural KwaZulu-Natal (Bergville, Appelsbosch

and Ixopo) and Limpopo (Worcester, Turkey and Santeng).

2.3.Data generation methods

Six months of intensive engagement with participants ensured quality and rigour of the study through

collaborative research (Maree, 2012). Data was generated through four main steps.

The first step involved collecting from secondary data sources which included financial records of

VSLAs and MDF’s reports. The second step involved observations of groups during their meetings. An

observations schedule was used to understand meeting procedures, recording of transactions and other

processes involved in a VSLA meeting. The third step involvedin-depth interviews and the final step

involved seven focus group discussions with participants from VSLAs and traditional stokvels. The size

of focus groups ranged between 8 and 15 participants. A focus group discussion schedule was used to

guide the engagements.

2.4.Data analysis

Finally, thematic content analysis was used. Data analysis in an interpretivist study begins as soon as

data collection starts. Thematic analysis is a procedure for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns

within data (Braun & Clarke, 2013). According to Maguire and Delahunt (2017), the significance of

thematic content analysis is that it helps the researcher to interpret and make sense of data generated as

well as analysing findings across a number of cases, drawing categories and common thematic elements

(Riessman, 2008). Similarly, Braun and Clark (2006), thematic analysis is a useful research tool that

provides flexibility in identifying,analysing, and reporting patterns. Thematic analysis is used in this

study for two main reasons associated withovercoming the challenge of cluttering the reader with

disconnected data. Firstly, thematic analysis allows the researcher to present perspectives for the

participants and especially in capturing unanticipated insights from the participants. Secondly, thematic

analysis helps the researcher to adopt a structured approach in synthesising data and consequently

producing a clear and organised report that is friendly to read. All interviews were conducted in IsiZulu

and translated back to English. The followingthree major stages of analysing data were used:

•Coding and searching for themes: In this phase, significant patterns in the datawere identified.

Related codes were groups in relation to their significance in the study and how they responded to

the research questions.

•Reviewing themes: The interest of this phasewas to identifyoverlapping themes in relation to

empirical data and HCD theoretical framework.

•Defining themes: This stage involved further refinement of themes and generating sub-themes. The

main focus of this stage was to see how the themes relate to each other resulting in a thematic map

that provided the narratives of community-based informal financialservices as told by the

participants.

24

2.5.Results and analysis

Study Area

Participants for the study were drawn from rural KwaZulu Natal (Bergville, Appelsbosch and Ixopo)

and Limpopo (Worcester, Turkey and Santeng). These rural villages are challenged by land degradation

that is slowly eating away arable land and frustrating the interaction of facets of smallholder farming

systems and livelihoods. Likemost rural communities in South Africa in general, women and the youth

are the bearers of social and economic marginalisation. The study areas are characterised by high levels

of poverty, inequality and unemployment making it most relevant for the research. High levels of

poverty, inequality and unemployment are persistent despite the provision of electricity, access roads,

schools and a regional hospital by government agencies.

The vulnerability among rural households is exacerbated by inability of decision-makers to identify and

accommodate the specific needs of those who are most vulnerable and certainly not represented by the

loudest voices in their communities. VSLA members participate in food security and small scale

farming, producing largely maize and other field crops, vegetables and fruit as well as rearing livestock

(mainly chickens, goats, pigs and cattle).

The study area bears the following significance. First, peoplefrom these villages must make provisions

for travel and associated opportunity costs to commute to nearest urban centres in order toaccess goods

and public services. Secondly, female-headed households and smallholder farmers struggle to produce

enough food to meet their needs and consequently miss the opportunity of supplying the local markets.

In other words, they grow food to eat first and sell small quantities of surplus irregularly. Although

they have some access to land, however, high levels of competition suppress profitability because

farmers tend to produce similar crops to other villages.

Profile of participants

Participants of the study were drawn from smallholder farmers participating in MDF programme.

Smallholder farmers are members of village level CRA learning groups and work with a basket of CRA

practices to improve production and productivity across the whole farming system - vegetables, fruit,

field crops and livestock. Further committees and structures emanate for the learning groupssuch as

the VSLAs, local marketing groups, livestock associations, farmer centres, water committees etc. These

learning groups link with traditional councils, local municipalities and other external role players.

Gender, marital status and age

44 (88%) respondents were drawn from MDF supported VSLAs, 3 (6%) participated in stokvels that

are not supported by MDF and 3 (6%) did not participate in any VSLAs or stokvels.

Gender

Marital Status

Age

Women

Men

Single

Married

18 – 35

26 – 55

55+

44

6

23

27

11

20

19

Table 1showing gender and age of participants

25

The above table shows that 88% of the participants were women. 11 were women aged 35 years and

younger. All men were older than 55 years. These participants lived with 172 adults and 181 children.

However, only 165 children received child support grants from the government. Only 12 participants

have senior certificates (grade 12).

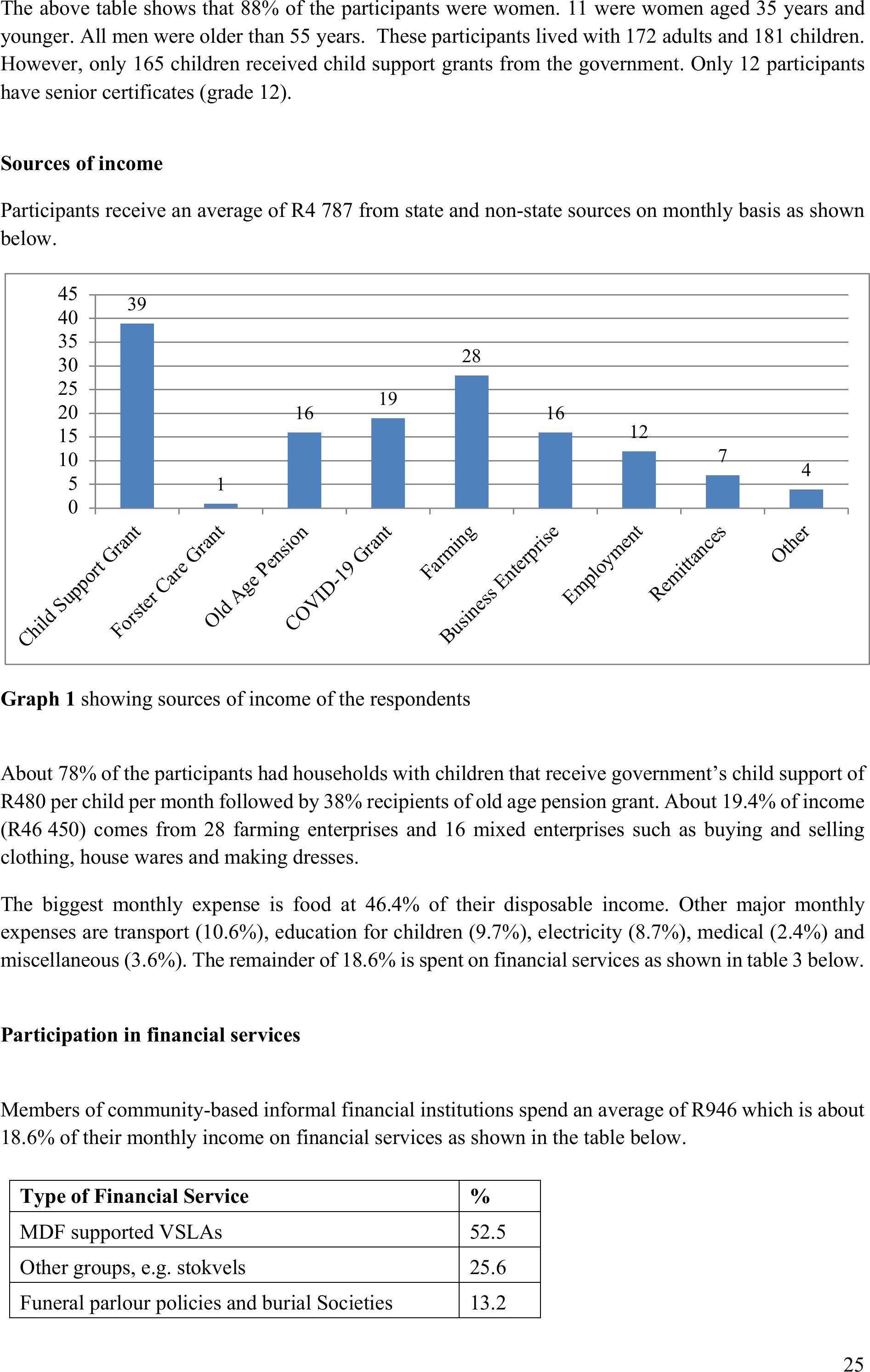

Sources of income

Participants receive an average of R4 787 from state and non-state sources on monthly basis as shown

below.

Graph 1 showing sources of income of the respondents

About 78% of the participants had households with children that receive government’s child support of

R480 per child per month followed by 38% recipients of old age pension grant. About 19.4% of income

(R46450) comes from 28 farming enterprises and 16 mixed enterprises such as buying and selling

clothing, house wares and making dresses.

The biggest monthly expense is food at 46.4% of their disposable income. Other major monthly

expenses are transport (10.6%), education for children (9.7%), electricity (8.7%), medical (2.4%) and

miscellaneous (3.6%). The remainder of 18.6% is spenton financial services as shown in table 3 below.

Participation in financial services

Members of community-based informal financial institutions spend an average of R946 which is about

18.6% of their monthly income on financial services as shown in the table below.

Type of Financial Service

%

MDF supported VSLAs

52.5

Other groups, e.g. stokvels

25.6

Funeral parlour policies and burial Societies

13.2

39

1

16 19

28

16

12

74

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Child Support Grant

Forster Care Grant

Old Age Pension

COVID-19 Grant

Farming

Business Enterprise

Employment

Remittances

Other

26

Type of Financial Service

%

Life insurance with a formal insurer

2.9

Savings accounts with banks

5.8

Table 2showing financial services that are used by participants use

This means that an individual member of a VSLA has a capacity of spending about R11352 per annum

where about R1800 is spenton insurance products and the rest is invested in VSLAs’, stokvels and

savings accounts with banks.

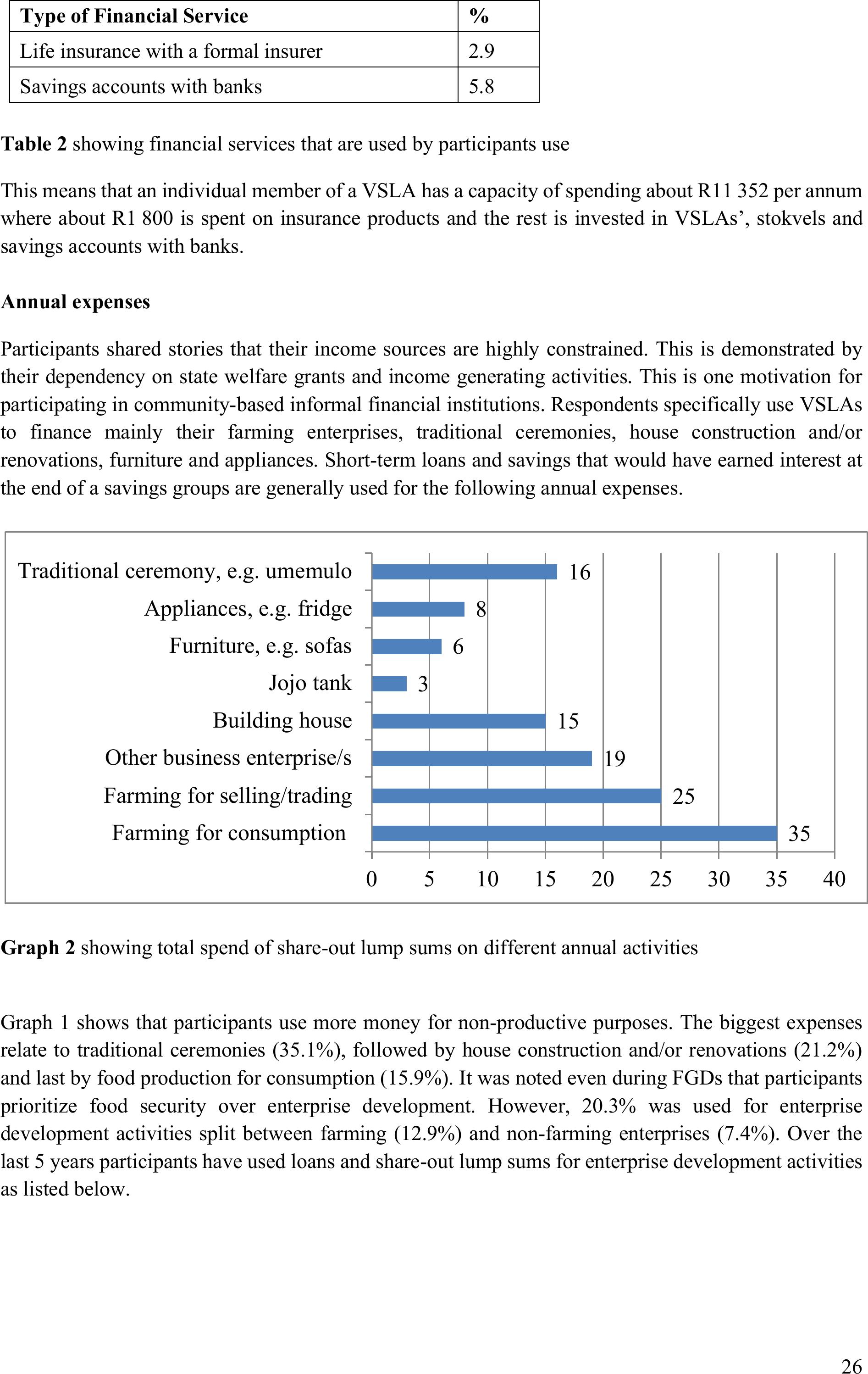

Annual expenses

Participantsshared stories that their income sources are highly constrained. This is demonstrated by

their dependency on state welfare grants and income generating activities. This is one motivation for

participating in community-based informal financial institutions. Respondents specifically use VSLAs

to finance mainly their farming enterprises, traditional ceremonies, house construction and/or

renovations, furniture and appliances. Short-term loans and savings that would have earned interest at

the end of a savings groups are generally used for the following annual expenses.

Graph 2showing total spend of share-out lump sums on different annual activities

Graph 1 shows that participants use more money for non-productive purposes. The biggest expenses

relate to traditional ceremonies (35.1%), followed by house construction and/or renovations (21.2%)

and last by food production for consumption (15.9%). It was noted even during FGDs that participants

prioritize food security over enterprise development. However, 20.3% was used for enterprise

development activities split between farming (12.9%) and non-farming enterprises (7.4%). Over the

last 5 years participants have used loans and share-out lump sums for enterprise development activities

as listed below.

35

25

19

15

3

6

8

16

0510 15 20 25 30 35 40

Farming for consumption

Farming for selling/trading

Other business enterprise/s

Building house

Jojo tank

Furniture, e.g. sofas

Appliances, e.g. fridge

Traditional ceremony, e.g. umemulo

27

Graph 3showing the use of loans for enterprise development

The tables and graphsabove showed the socio-economic information of the participants in the study.

These are gender and age distribution, marital status, income sources and monthly and annual expenses.

These graphs demonstrate that the significance not only lies on their sources of income, but also on the

use of loans and lump sums of money they receive at the end of saving cycles. The top three uses of

money are traditional ceremonies, house building and/or renovations and farming. Itwas found that

farming was dominated by cropping which was split between consumption and farming enterprise.

2.6.Financial Services in the Villages

The study confirmed that all the villagers have access to the following group-based financial services.

Description

Challenges and Risks

Traditional burial

societies

The main purpose is to provide social relief

and support during the bereavement of a

member. Membership, rules of participation,

premiums, policies for pay-outs, etc. are

governed by the constitution. Some group pay

cash, some provide a service and some do

both. Premiums can be paid weekly of

monthly as determined by a constitution.

Simultaneous claims can reduce individual

payments or worse, deplete the group fund.

Members who do not experience death

tragedies in their families tend to withdraw

after few years. Lesser death claims grow

the group fund and can lead to fraudulent

behaviours by the leadership of the group.

66.1%

17.5%

4.9%

0.5% 10.9%

Cropping

Broilers

Layers/eggs

Farmer Centre

Other enterprises

28

Description

Challenges and Risks

Traditional stokvels

Traditional stokvels take many shapes.

However, the most common feature is that

these groups have a clear target goal, for

example, bulk buying of groceries at the end

of the year, house construction, buying

furniture and appliances, etc. A fixed

contribution is decided at the start of the

savings cycle and monthly contributions are

usually deposited at the bank. These groups

are built on the concept of delayed

gratification. The most obvious benefit of

these groups is that they help their members to

buy household assets and to afford expensive

goods.

Many of these groups are constrained by the

fixed mentality that their cycles must run

alongside the calendar – in that their goals

must be achieved at least by end of the year.

While it is good to keep the money in the

bank, inflation, low interest rates and bank

charges tend to depreciate the group funds.

Silent voices, that is, the most poor are

usually disadvantaged by louder voices in

these groups.

Investment clubs

The purpose of investment clubs is to run a

lending business in the village. Members pool

their contributions on monthly basis. The total

fund is forcefully given to few members of the

group as loans for them to extend these loans

to non-members of the group.These groups

charge anything between 30% and 40%

interest per month. Interest earned accrues to

individual members who are successful in

settling their loans.

These groups have complex record keeping

systems to capture interest due to borrowers

(who are members of the group). Interest

does not accrue to the group.This means

that members who do not take out loans do

not receive interest. Obviously, these groups

risk their funds by lending to external

borrowers. Lastly, these groups are

infamous for high levels of fraud by their

leaders.

Merry go rounds

Members of these groups take turns to receive

total contributions made by all members in a

month. The group dissolves when all members

have received their lump sums. Record

keeping is very simple as there are no loans

issued and interestcalculation.

The biggest risk is carried by members at the

tail-end of the cycle because they remain

unsure if they will be paid as the first few

members were. Similarly, those who receive

pay-outs at the start of the cycle are likely to

miss making contributions due.

Saving up and saving down

Members agree to start with small amounts

which grow by an agreed percentage rate. This

is referred to as “saving up”. The most

common saving up model starts with R50 in

the first month, R100 in the second month,

R150 in the third month and growing to R600

by the 12thmonth. Saving down is thedirect

opposite, for example,members will start

saving R600 in the first month down to R50 by

the 12thmonth. All contributions are deposited

in the bank.

This approach attracts similar weaknesses

and challenges faced by traditional stokvels.

However, members tend to face additional

stresses stemming from changing

contributions – and especially, the “saving

up” method.

29

Description

Challenges and Risks

VSLAs

This model is described in detail insub-section

3.5 above. VSLAs draw good and progressing

practices from traditional groups as well as

from formal financial institutions when it

comes to developing loan terms. This helps to

curb the appetite for charging exorbitant

interests and extending loans to non-members.

Most groups cap loan amounts as a risk

management strategy to mitigate

delinquency. The largest majority of

VSLAs cap loans to R5000. There are two

limitations stemming from this. Farmers

need more than R5000 and more than three

to four months to settle the loan.

Bulk Loan Fund

Bulk Loan Fund (BLF) is established by

members ofexisting VSLAs for the purpose of

bulking of loan fund. VSLAs must operate in

the same community. Members agree on a

once-off annual lump sum contribution at the

establishment meeting. The minimum

duration of the cycle is 5 years. There are no

monthly contributions. Loans specifically

ring-fenced for productive activities. A flat

interest rate of 15% is charged on loans which

are payable over6 months. Interest is shared-

out at the end of the third year.

Members of this group struggle to invest

larger once-off lumps that they require to

meet financialexpectationsof thefarmers in

the first year. However, this is circumvented