i

Water Research Commission

Submitted to:

Dr Gerhard Backeberg

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Prepared By:

Project team led by Mahlathini Development Foundation.

Project Number: K5/2719/4

Project Title: Collaborative knowledge creation and mediation strategies for the dissemination of

Waterand Soil Conservation practices and Climate Smart Agriculture in smallholder farming

systems.

Deliverable No.3:Report-Decision support system for CSA in smallholder farming developed

Date: January 2018

Deliverable

3

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 2

Submitted to:

Executive Manager: Water Utilisation in Agriculture

Water Research Commission

Pretoria

Project team:

Mahlathini Development Centre

Erna Kruger

Sylvester Selala

Mazwi Dlamini

Khethiwe Mthethwa

Temakholo Mathebula

Institute of Natural Resources NPC

Jon McCosh

Rural Integrated Engineering (Pty) Ltd

Christiaan Stymie

Rhodes University Environmental Learning Research Centre

Lawrence Sisitka

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 3

CONTENTS

FIGURES 6

TABLES 6

1OVERVIEW OF PROJECT AND DELIVERABLE7

Contract Summary7

Project objectives7

Deliverables 7

Overview of Deliverable 38

2decision support system methodology10

Introduction 10

Decision Support System for CSA in smallholder farming systems21

Issues, constraints, risks and vulnerabilities23

Community level climate change adaptation analysis23

Farmer typology24

Potential adaptive measures and criteria for assessment24

Practices 26

Prioritization of practices for farmer innovation28

Monitoring, review and re-planning28

Indicators 28

3Process framework30

Climate Smart Agriculture: Process Facilitation30

Introduction 30

Design of the CCA community level workshop outline33

Testing the process38

4Site selection40

Introduction 40

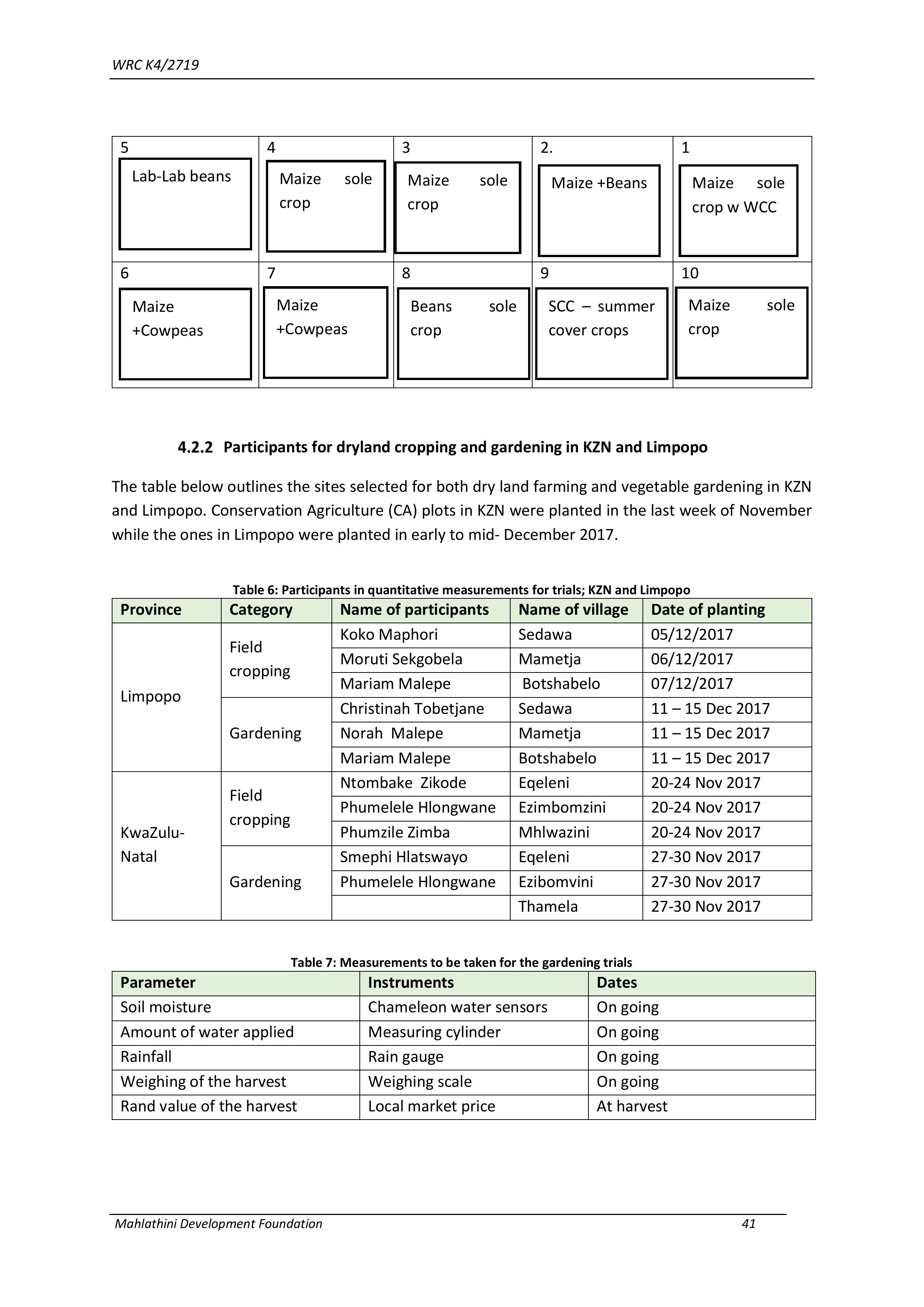

Work Plan for measurements for KZN and Limpopo for 2017/2018 season40

Plot layout40

Participants for dryland cropping and gardening in KZN and Limpopo41

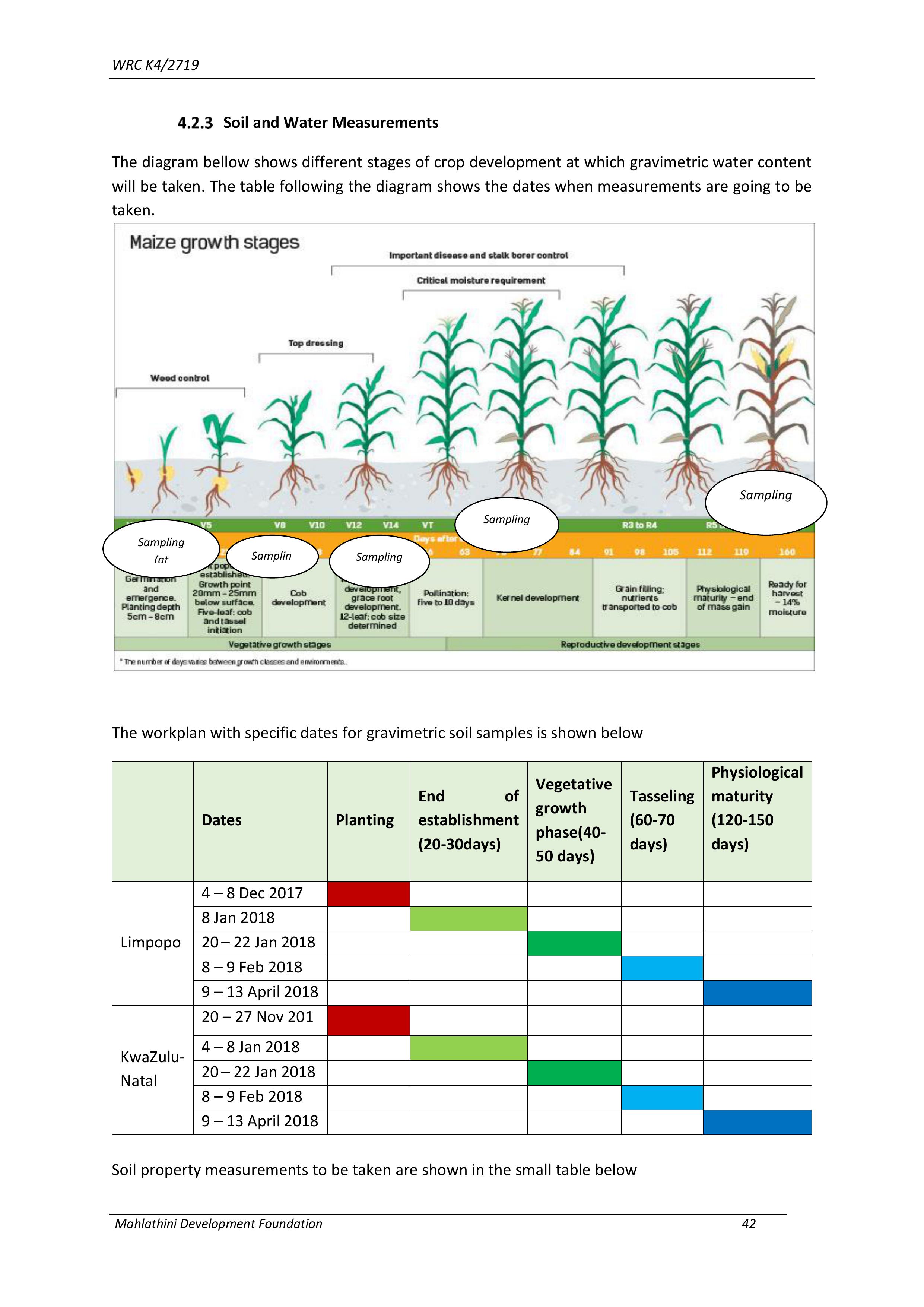

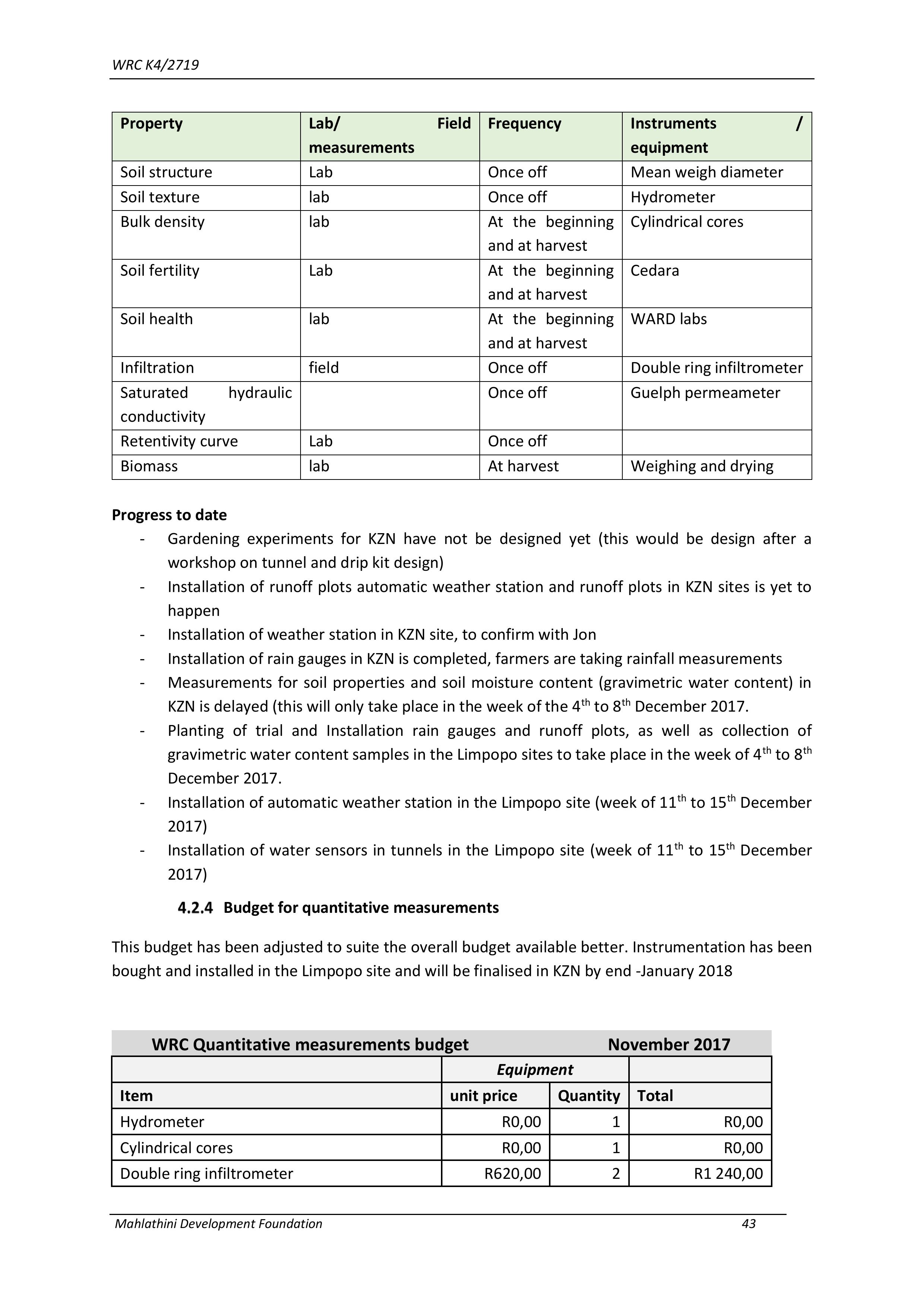

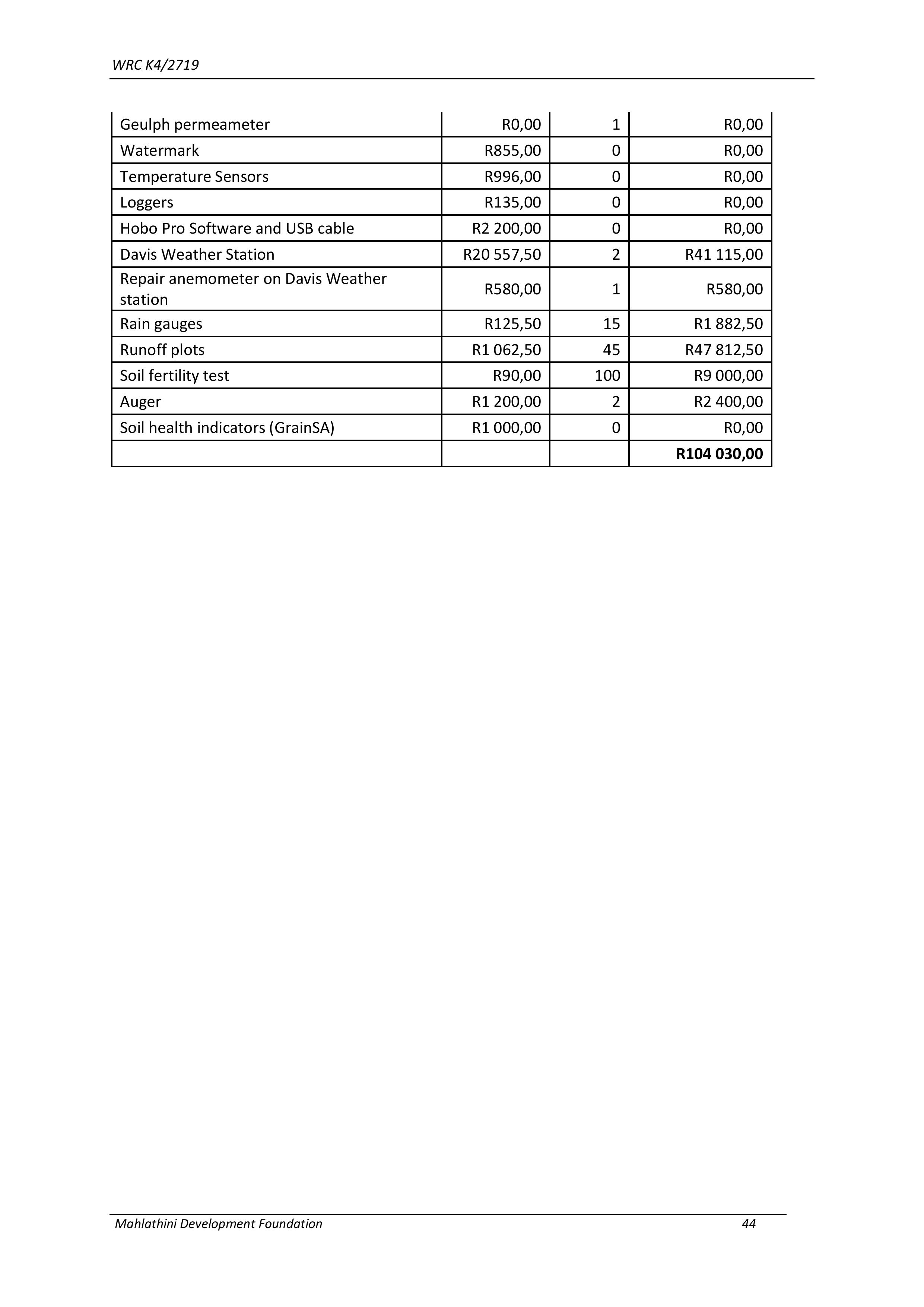

Soil and Water Measurements42

Budget for quantitative measurements43

5Communication strategy45

Introduction and Background45

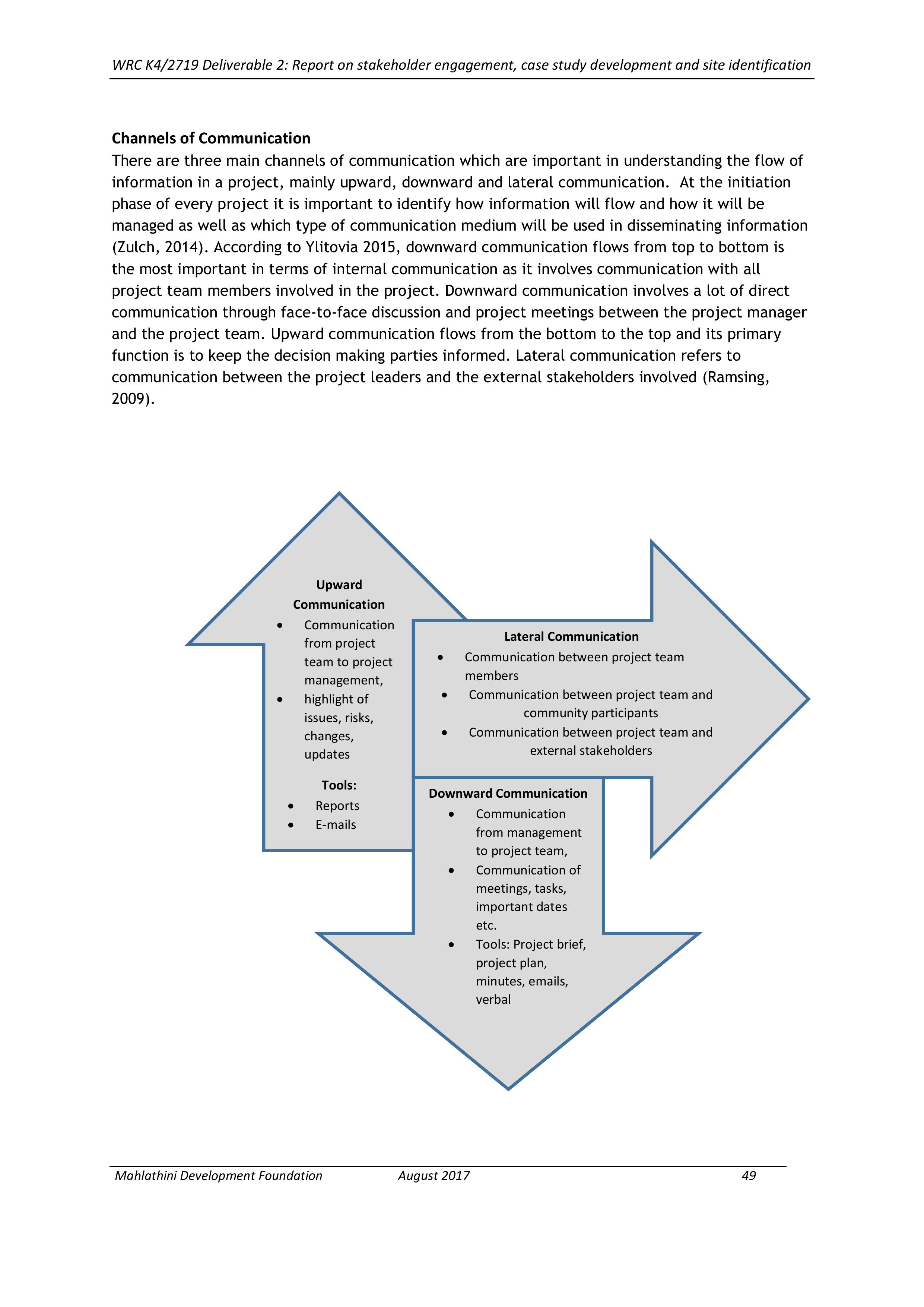

Levels of Communication45

The Need for a Communication Strategy50

Partners and Stakeholders51

Promotion and Sharing of the Decision Support System53

Potential Users of the DSS53

Sharing with Smallholder Farmers54

Sharing with NGOs, Agricultural Extension and Advisory Services and other Training

Institutions/Organisations 54

Sharing Internationally54

Communication with and between the facilitators and farmers55

Introduction 55

Participatory videos55

WhatsApp 56

Radios 58

Audio cassettes59

Community Group meetings60

Demonstrations 60

Farm visits/ homestead visit61

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 4

Farmer-to-farmer Extension model62

Office Calls62

Telephone calls63

Informal contacts63

Internet-based platforms63

‘Hard Copy’ Materials63

Considerations in determining appropriate educational and communication methods65

6Capacity building66

Team Capacity building66

Postgraduate students66

Sanelisiwe Tafa-Fort Hare University (EC).66

Khethiwe Mthethwa (University of KwaZulu Natal)67

Mazwi Dlamini (UWC-PLAAS)67

Palesa Motaung (University of Pretoria)68

Sylvester Selala (UKZN)68

7Appendix 1: WRC PLANNING MEETING: 09-11 October 201769

DAY 1: AGENDA69

Decision Support System69

(Part 1)69

Decision Support System (Part 2)69

Decision Support System (Part 3)70

Deliverable 3 Outcomes70

1. Practices 70

2 Categories70

3Decision support system: implementation method71

AWARD CASE STUDY –An example of CC dialogue facilitation at community level71

GrainSA Conservation Agriculture72

First Rand Foundation /WESBANK/FS Funding72

DAY 2 Agenda72

1. Presentations 73

Infrastructure/ engineering Practices: Chris73

AMANZI FOR FOOD: Lawrence74

Agroforestry: John75

Conservation Agriculture: Sylvester75

Coming up with a Decision Support System75

Categories 75

Group work: Technical aspects: Report back77

3. Quantitative measurements78

Site selection80

ToC for Deliverable 381

8APpendix 2: DICLAD Modules 2 & 3 with AgriSI stakeholders in the Lower Olifants

:24th to 26th Oct 201781

Overall purpose82

Expected outcomes82

Agenda 82

Participants 82

Recap of concepts covered in DICLAD Module 182

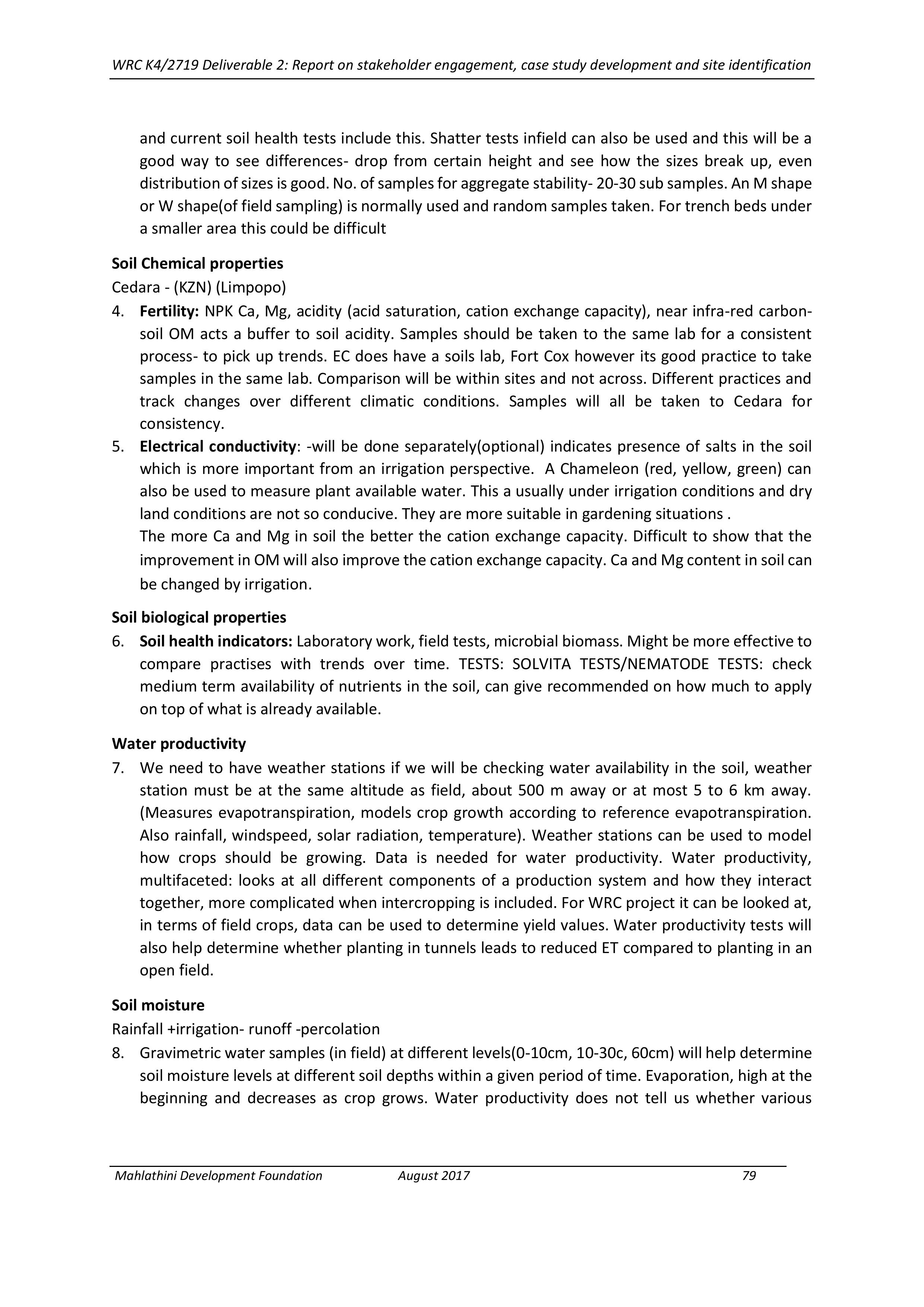

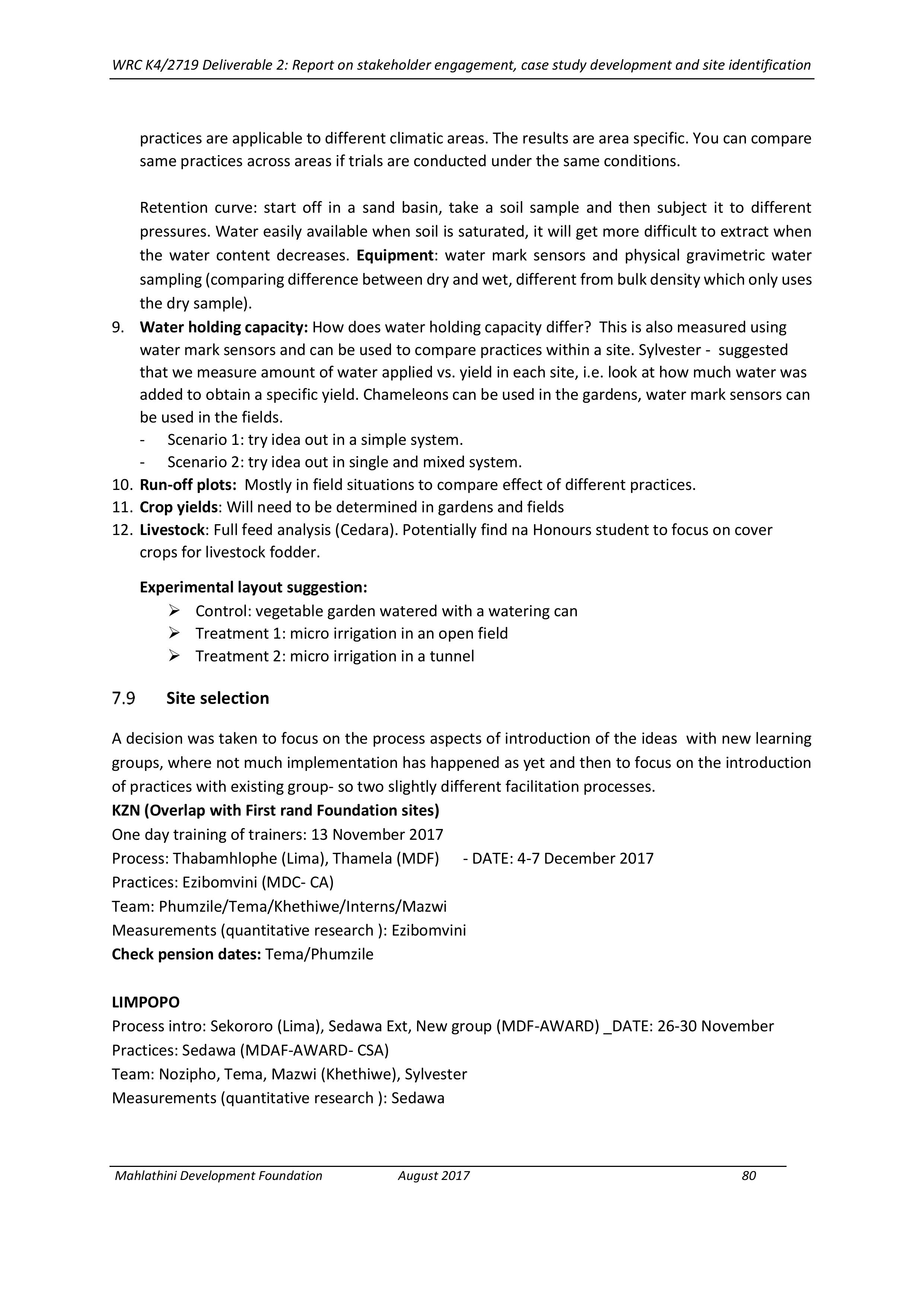

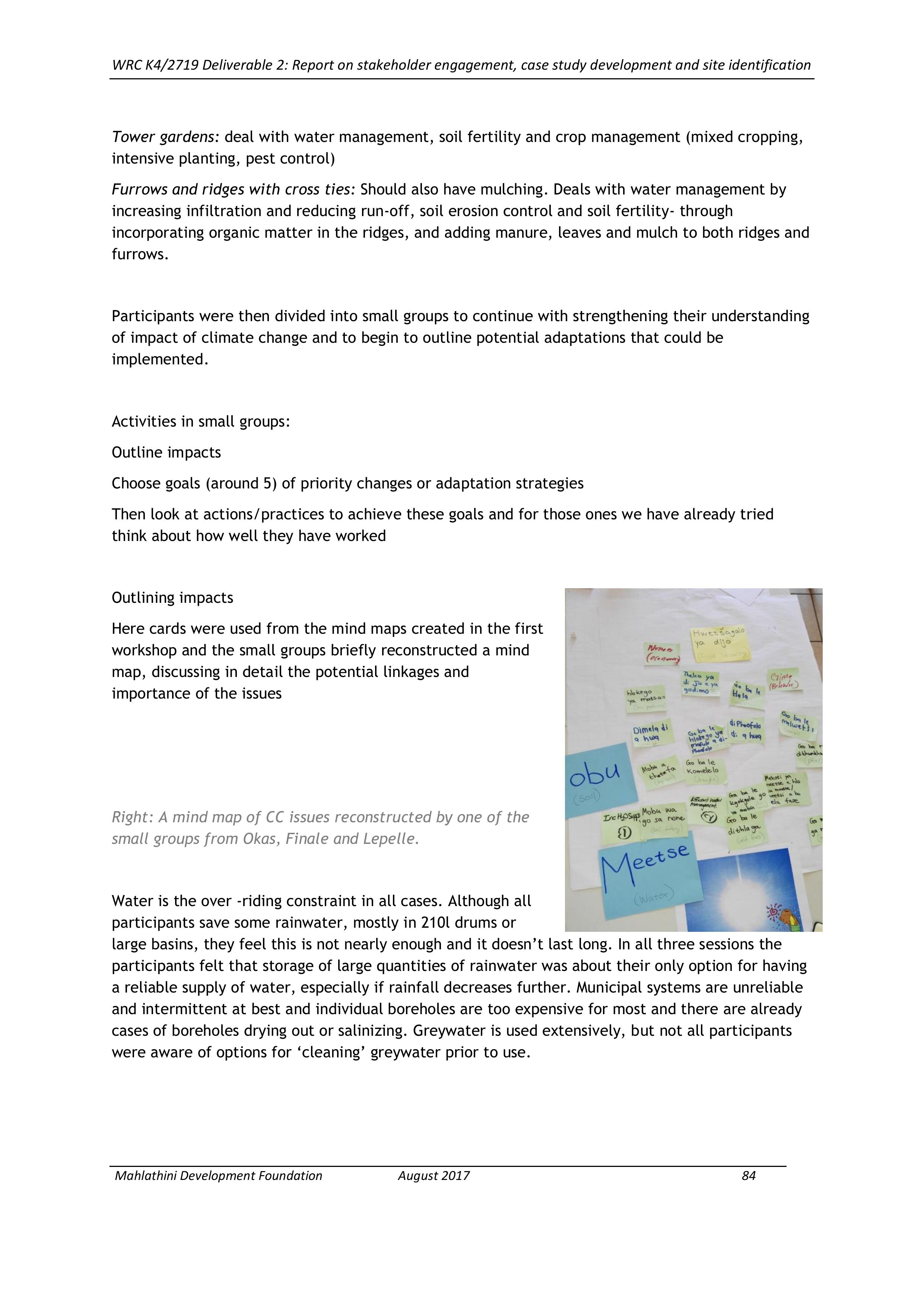

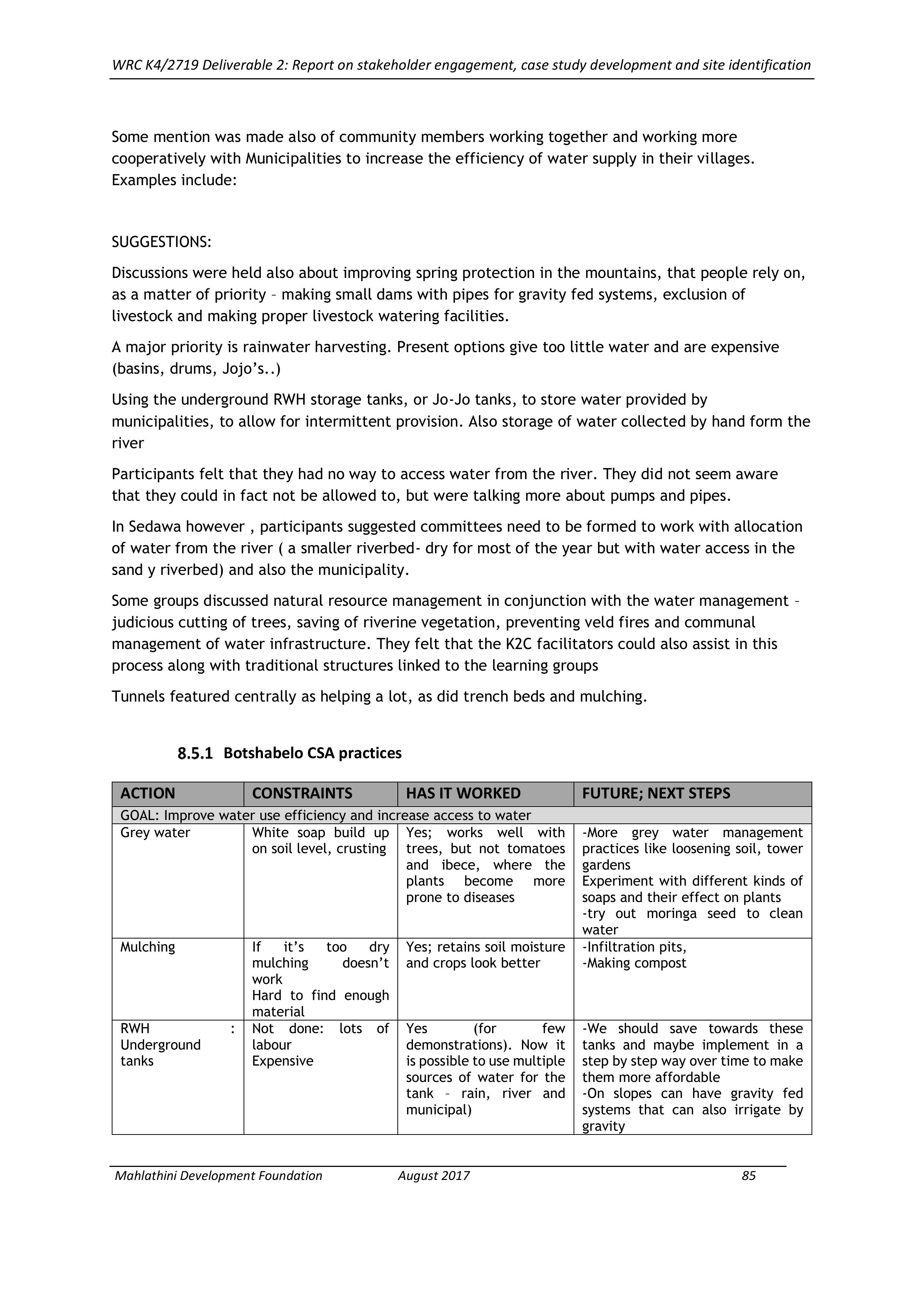

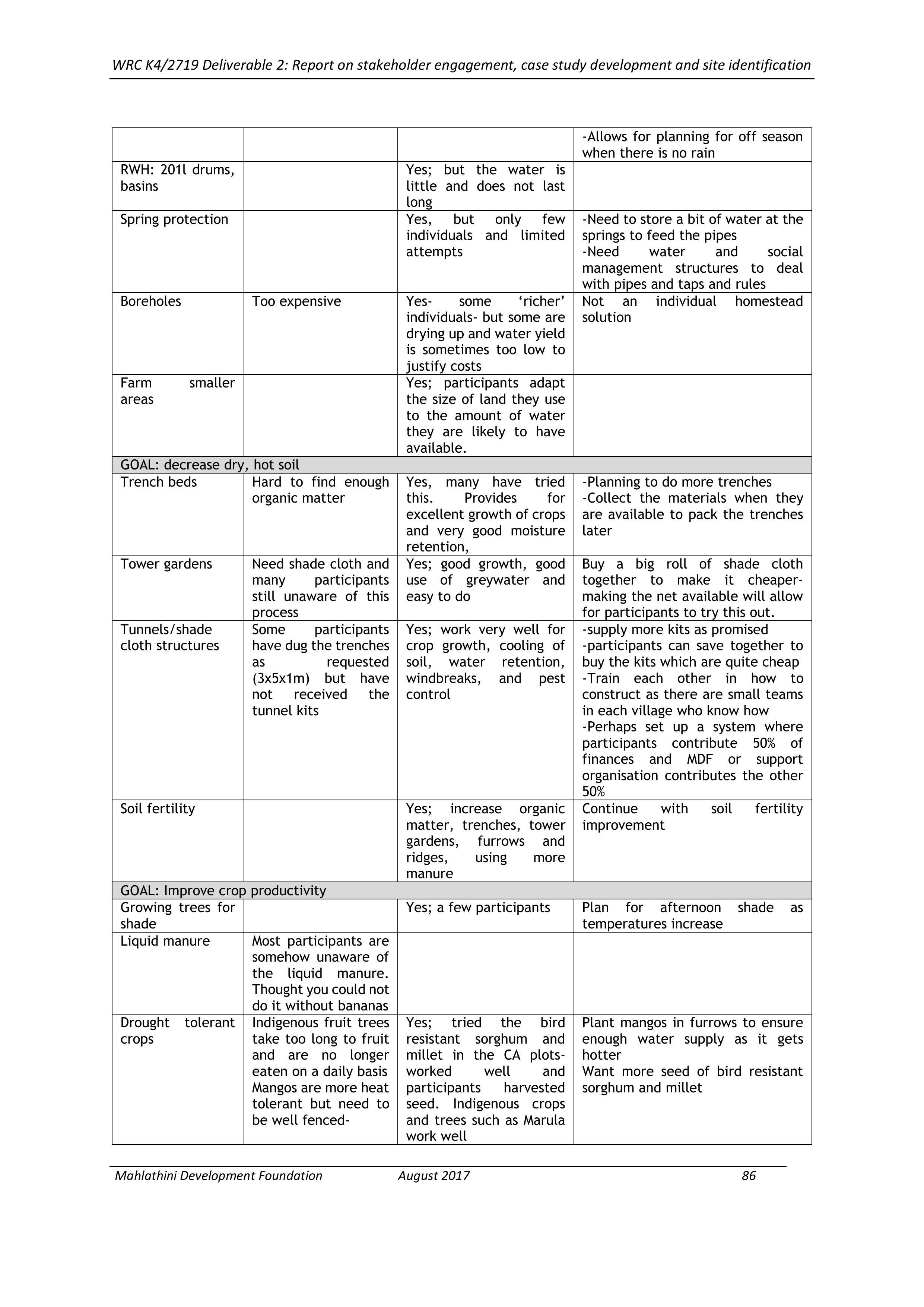

Botshabelo CSA practices85

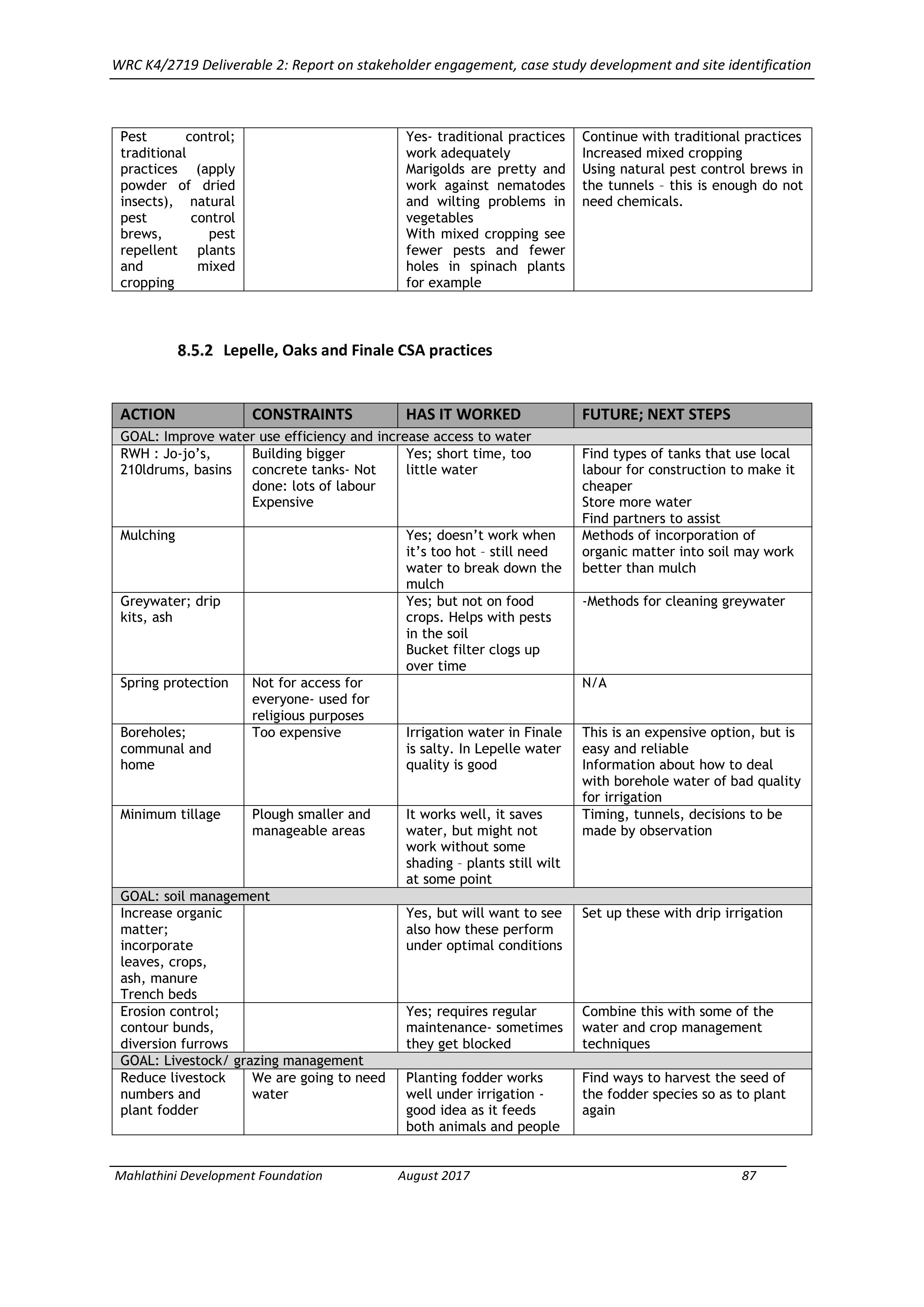

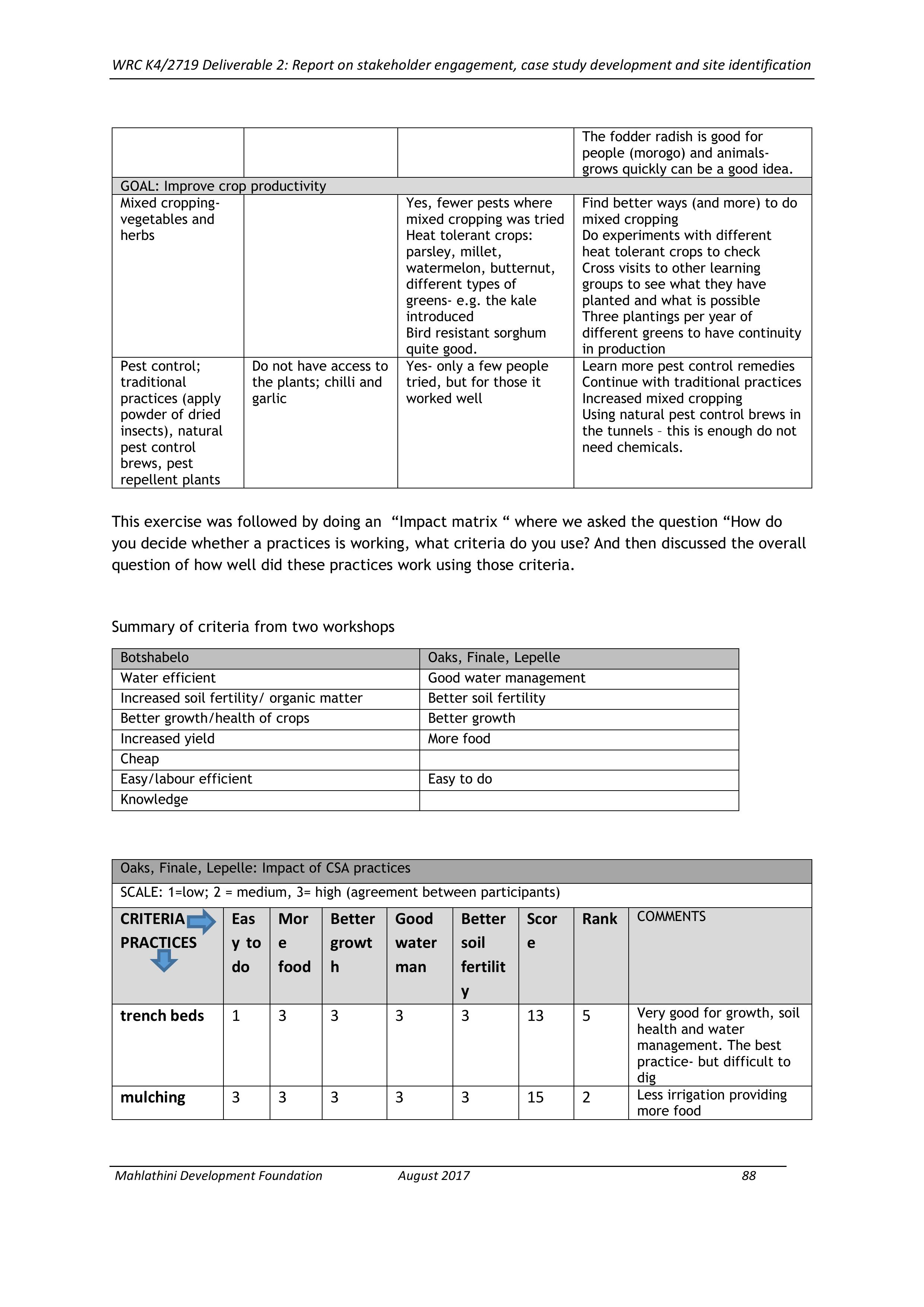

Lepelle, Oaks and Finale CSA practices87

Sedawa CSA practices89

Learnings 90

Future CC actions91

Planning for DICLAD-AgriSI Module 3 (2018)91

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 5

9APpendix 3: WRC-CCA Community workshop: Sekororo (Lima)_20171128-29 93

Introductions 93

Impacts of CC94

What is CC94

Impacts 94

Past, present future of farming activities in the area94

Past: 94

Present 94

Future 95

CC predictions and understanding95

CC impact mind mapping96

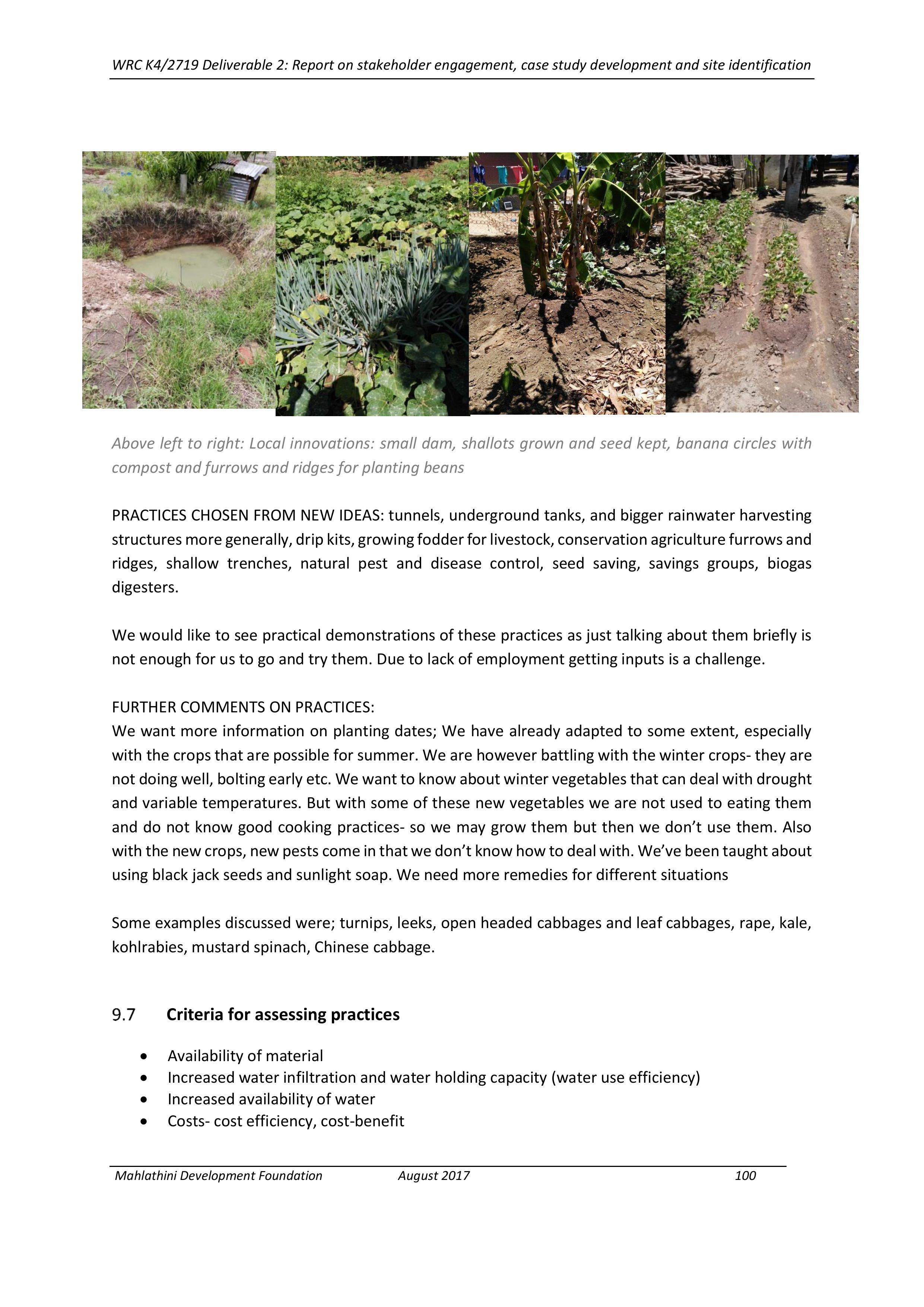

Assessment of potential practices98

Practices 99

Criteria for assessing practices100

10 References 102

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 6

FIGURES

Figure 1:Disaggregated prioritisation of practices (CIAT CSA_RA, 2016) .............................................14

Figure 2: decision making process (Adapted from Heinemann, 1988).................................................18

Figure 3: Dimensions of Vulnerability (CGIAR/CCAFS, 2015)................................................................19

Figure 4: Schematic for DICLAD; Facilitating Understanding of Climate Change and Adaptation

(AWARD, 2017).....................................................................................................................................20

Figure 5: The DSS for smallholder farming systems .............................................................................23

Figure 6: Simplified model of the Imvotho Bubomi Learning Network, Middledrift Area, Eastern Cape

..............................................................................................................................................................51

Figure 7: Audio cassettes......................................................................................................................60

TABLES

Table 1: Excerpt from the Amanzi for Food Navigation Tool, 2015......................................................15

Table 2 :Community level criteria for assessment of CSA practices; Nov-Dec 2017............................25

Table 3: Community resource map description and uses.....................................................................31

Table 4: Seasonal calendar description and uses.................................................................................32

Table 5:Seasonal calendar ....................................................................................................................32

Table 6: Participants in quantitative measurements for trials; KZN and Limpopo...............................41

Table 7: Measurements to be taken for the gardening trials...............................................................41

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 7

Report-DecisionsupportsystemforCSA

insmallholder farming developed

1OVERVIEW OF PROJECT AND DELIVERABLE

Contract Summary

Project objectives

1. To evaluate and identify best practice options for CSA and Soil and Water Conservation

(SWC) in smallholder farming systems, in two bioclimatic regions in South Africa. (Output 1)

2. To amplify collaborative knowledge creation of CSA practices with smallholder farmers in

South Africa (Output 2)

3. To test and adapt existing CSA decision support systems (DSS) for the South Africansmallholder

context (Outputs 2,3)

4. To evaluate the impact of CSA interventions identified through the DSS by pilotinginterventions

in smallholder farmer systems, considering water productivity, social acceptability and farm-scale

resilience (Outputs 3,4)

5. Visual and proxy indicators appropriate for a Payment for Ecosystems based model aretested at

community level for local assessment of progress and tested against field and laboratory analysis

of soil physical and chemical properties, and water productivity (Output 5)

Deliverables

No

Deliverable

Description

Target date

FINANCIAL YEAR 2017/2018

1

Report: Desktop review of

CSA and WSC

Desktop review of current science, indigenous and traditional

knowledge, and best practice in relation to CSA and WSC in the

South African context

1 June 2017

2

Report on stakeholder

engagement and case

study development and

site identification

Identifying and engaging with projects and stakeholders

implementing CSA and WSC processes and capturing case studies

applicable to prioritized bioclimatic regions

Identification of pilot research sites

1 September

2017

3

Decision support system

for CSA in smallholder

farming developed

(Report)

Decision support system for prioritization of best bet CSA options in

a particular locality; initial database and models. Review existing

models, in conjunction with stakeholder discussions for initial

criteria

15 January

2018

FINANCIAL YEAR: 2018/2019

4

CoPs and demonstration

sites established (report)

Establish communities of practice (CoP)s including stakeholders and

smallholder farmers in each bioclimatic region.5. With each CoP,

identify and select demonstration sites in each bioclimatic region

and pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range

of CSA and WSC strategies in homestead farming systems (gardens

and fields)

1 May 2018

5

Interim report: Refined

decision support system

for CSA in smallholder

farming (report)

Refinement of criteria and practices, introduction of new ideas and

innovations, updating of decision support system

1 October

2018

6

Interim report: Results of

pilots, season 1

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies, working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

31 January

2019

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 8

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/2020

7

Report: Appropriate

quantitative measurement

procedures for verification

of the visual indicators.

Set up farmer and researcher level experimentation

1 May 2019

8

Interim report:

Development of indicators,

proxies and benchmarks

and knowledge mediation

processes

Document and record appropriate visual indicators and proxies for

community level assessment, work with CoPs to implement and

refine indicators. Link proxies and benchmarks to quantitative

research to verify and formalise. Explore potential incentive

schemes and financing mechanisms.

Analysis of contemporary approaches to collaborative knowledge

creation within the agricultural sector. Conduct survey of present

knowledge mediation processes in community and smallholder

settings. Develop appropriate knowledge mediation processes for

each CoP. Develop CoP decision support systems

1 August

2019

9

Interim report: results of

pilots, season 2

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies, working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

31 January

2020

FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021

10

Final report: Results of

pilots, season

Pilot chosen collaborative strategies for introduction of a range of

CSA and WSC strategies , working with the CoPs in each site and the

decisions support system. Create knowledge mediation productions,

manuals, handouts and other resources necessary for learning and

implementation.

1 May 2020

11

Final Report: Consolidation

and finalisation of decision

support system

Finalisation of criteria and practices, introduction of new ideas and

innovations, updating of decision support system

3 July 2020

12

Final report - Summarise

and disseminate

recommendations for best

practice options.

Summarise and disseminate recommendations for best practice

options for knowledge mediation and CSA and SWC techniques for

prioritized bioclimatic regions

7 August

2020

Overview of Deliverable 3

The design of the decision support system is seen as an ongoing process divided into three distinct

parts:

➢Practices: Collation, review, testing, and finalisation of those CSA practices to be included.

Allows for new ideas and local practices to be included over time. This also includes

linkages and reference to external sources of technical information around climate change,

soils, water management etc and how this will be done;

➢Process: Through which climate smart agricultural practices are implemented at

smallholder farmer level. This also includes the facilitation component, communities of

practice, communication strategies and capacity building and

➢Monitoring and evaluation: local and visual assessment protocols for assessing

implementation and impact of practices as well as processes used. This also includes site

selection and quantitative measurements undertaken to support the visual assessment

protocols and development of visual and proxy indicators for future use in inactive based

support schemes for smallholder farmers

Activities in this four month period have included:

-Team planning meeting(9-11 October 2017)

-Dialogues in climate change adaptation- including assessmentof practices –Limpopo (25-27

October 2017)

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 9

-Design and implementation of process methodology for introduction of climate smart

agriculture and practices at community level; 4 villages across KZN and Limpopo(27Nov-1

Dec and 4-8 Dec 2017)

-Training of trainers process for introduction of process methodology(20 Nov 2017)

-Visual and descriptive outlines of all practices in the database; Attached as a separate

document

-Set up of sites for quantitative measurements: KZN–field sites(Ezibomvini, Eqeleni,

Mhlwazini); garden site (Ezibomvini), Limpopo –field sites (Sedawa, Mametje, Botshabelo)

garden site (Sedawa)

-Capacity building and publications: Research presentations and chapters,newsletter

articles (GrainSA), conferences (PLAAS postgraduate conference) and awareness raising

events (Swayimane Conservation Agriculture day); Attached as separate Documents.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 10

2DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM METHODOLOGY

By Lawrence Sisitka

Introduction

Section 2.3.3 in Deliverable 2 provided a broad introduction to and analysis of some existing

Decision Support Systems (also known as Decision Support Frameworks) in the global agricultural

sector. It was made clear that most such DSS have been developed to inform policy making at

national or regional levels. The developers of the framework “targetCSA” for example are very

specific that: The spatially-explicit multi-criteria decision support framework “targetCSA” … aims

to aid the targeting of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) at the national level(emphasis added)

(Brandt, Kvakić, Butterbach-Bahl, & Rufino, 2017)

Similarly the CCAFS Climate Smart Adaptation Prioritisation (CSAP) toolkit is intended to: … arm

policymakers with the information that they need to choose the best climate-smart interventions

in the short, medium and long term under varying climate scenarios(emphasis added) (Corner-

Dolloff, 2015).

Such wide-scale DSS can certainly provide a broad picture of where particular crops and particular

CSA practices may be most appropriate, according to bio-geographic and climatic zones, climate-

change predictions and other metrics such as soil types and fertility. In this way they can frame

the options for farmers in different areas.

In Deliverable 2 it was also made clear that South Africa currently does not have a DSS, or

equivalent, for agriculture in relation to climate change, at either national or provincial levels,

although it has been proposed that the National Climate Change Response Policy (NCCRP) (DEA,

2011) can, together with the Climate Change Sector Plan for AgricultureForestry and Fisheries

(CCSP) (DAFF, 2013) provide something of a framework for CSA. However it has also been suggested

that these are both too broad and too commercial in focus to be of much value to the small-scale

and emergent farmers who are the focusof this CSA project. This is not to say that they have no

value, and any development of a DSS within this project must certainly correlate with these

policies. But without clear national and provincial frameworks within which decisions can be made

at a local level, such decision-making will inevitably be based on understandings of local

conditions, augmented by knowledge of wider-scale climate predictions. In relation to the latter

South Africa is fortunate to have the South African Risk and Vulnerability Atlas (SARVA) portal

(www.SARVA.dirisa.org), through which up-to-date information on climate predictions for all parts

of the country, and a host of related information, can be accessed. However, in the form presented

in the portal, much of this information is perhaps not readily accessible to the majority of farmers,

or indeed, many people working with them.

As a DSS at a more local level, the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) has

developed a Climate Smart Agriculture Rapid Appraisal (CSA-RA) methodology, described as “A tool

for Prioritisation of Climate Smart Agriculture across Landscapes”(Mwongera, et al., 2016)(. This is

designed for use at the household-farm, community-landscape, and sub-regional scales, and is

based on a participatory approach, with farmers and external specialists, to the identification of

site-specific CSA interventions.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 11

Access to information of all kinds is absolutely essential for effective decision-making, and much of

the information generated and used in formal DSS, such as those described above, is highly

technical and captured in ways inaccessible to most farmers. Many national and regional-scale DSS

are internet-based, and involve complex analyses, using sophisticated modelling and computational

tools considerably beyond the capacity of all but the specialists who develop such tools to grasp.

While such information and analyses can to some degree be mediated through careful facilitation,

the ownership of information, and process and indeed the decisions themselves is often left

strongly in the hands of the specialists. In developing DSS for farmers, the more information is

directly accessible and understood by them, and the more open and comprehensible the analyses,

the better, as they will then have stronger ownership of these, and of the decisions taken through

them. The CIAT approach, described above, draws strongly on information from the farmers

themselves, although also incorporating specialist technical information on climate change

predictions and would appear to place the ownership of decision making quite firmly in the

farmers’ own hands.

Criteria

DSS require the identification of a range of technical and social criteria relevant to the context,

which decision-makers need to analyse in order to reach their decisions. The basis of the analysis

in Decision Support Systems is often an assessment of vulnerability. TargetCSA, for example uses a

range of ‘climate change vulnerability indicators’ as follows:

Biophysical

•Annual precipitation (as an indicator for water availability and ecosystem productivity)

•Soil organic matter (as an indicator of soil fertility and ecosystem productivity)

Social

•Percentage of households with access to safe water sources (as an indicator of household well-

being)

•Literacy rate (as an educational indicator for adaptive capacity, i.e. for making informed decisions)

Economic

•Female participation in economic activities (as an indicator for women’s empowerment and

gender equity)

•Connectivity through transport infrastructure (as an indicator of farmers’ accessibility to markets)

It is worth remembering that targetCSA is a DSS developed for a broad spatial analysis, at either

national or regional levels, with the decision makers being mostly policy-makers, albeit with input

from some farmers. These fairly broad indicators are essentially proxies for complex biophysical,

social and economic realities, and are prone to considerable variation when applied on such a broad

scale. Their relevance in some situations may also be questionable, such as with literacy levels as a

proxy for adaptive capacity, suggesting that farmers with some formal education are more likely to

have this capacity than those without education. There is also the issue that on this scale farmers

are seen as a homogenous entity, rather than, as is the reality, a group of individuals with

individual circumstances, needs and aspirations.

In targetCSA these vulnerability indicators are linked to a range of generic CSA practices, or

practice approaches considered appropriate responses in the light of particular combinations of the

indicators. The practices identified, with their suggested links to the indicators are:

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 12

CSA Practices

•Improvement of soil fertility and soil management–linked to: soil organic matter and literacy rate

•Identification and distribution of drought tolerant cereal crops–linked to: annual precipitation

and literacy rate

•Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from thelivestocksector–identified as a mitigation

measure, linked to all the vulnerability indicators

•Improvement of water harvesting and water management–linked to: annual precipitation;

percentage of households with access to safe water sources; literacyrate; and connectivity

through transport infrastructure

•Identification and establishment of agroforestry practices–linked to: soil organic matter and

female participation in economic activities

•Implementation of livestock insurances–linked to: annual precipitation; percentage of households

with access to safe water sources; literacy rate; and connectivity through transport infrastructure

On the scale at which targetCSA is intended to operate as a DSS these generic practices can provide

useful guidance for which specific practices might be most appropriate in different areas.

For example, in Kenya, where target CSA was piloted, areas were identified for their suitability for

different generic practices:

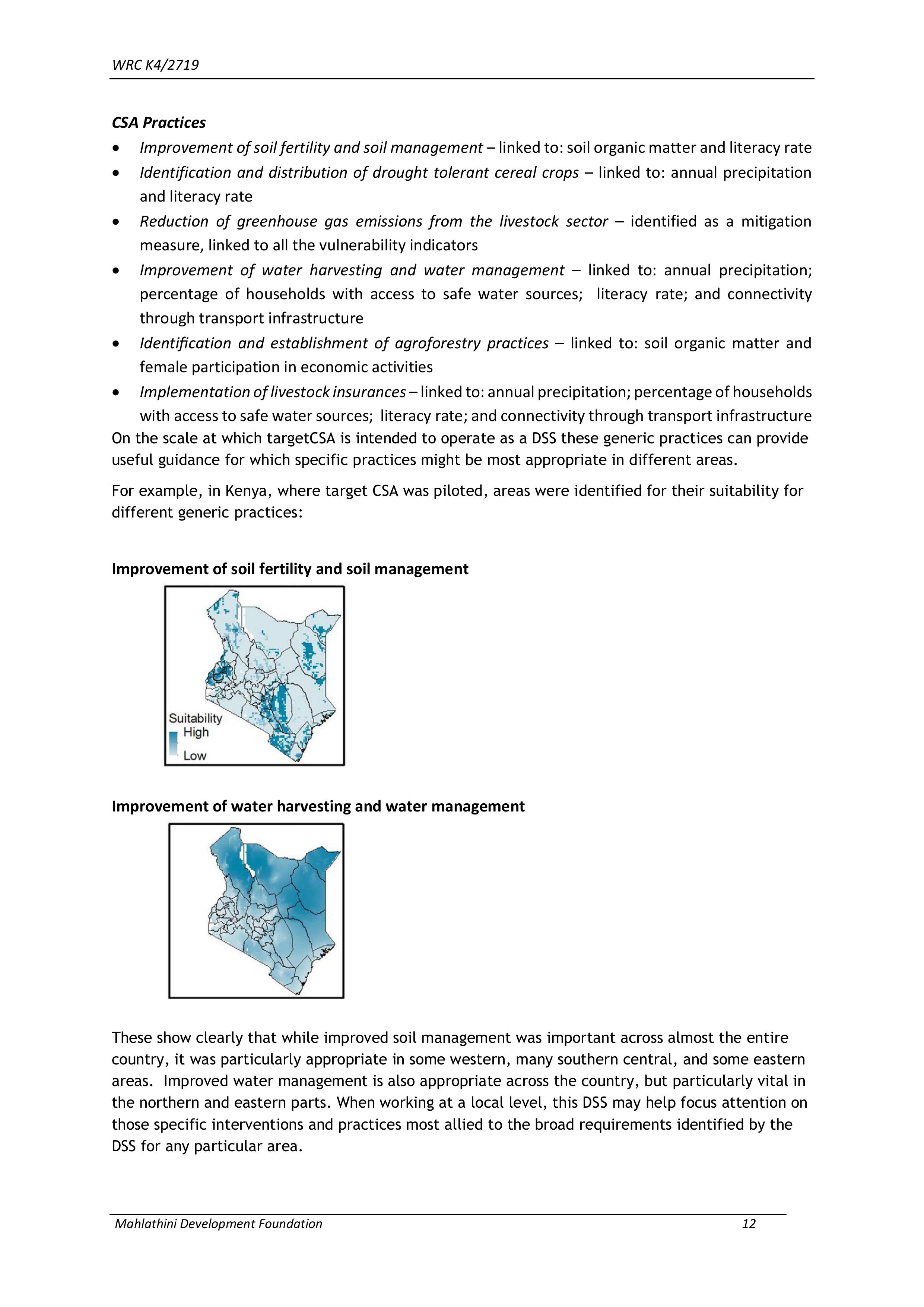

Improvement of soil fertility and soil management

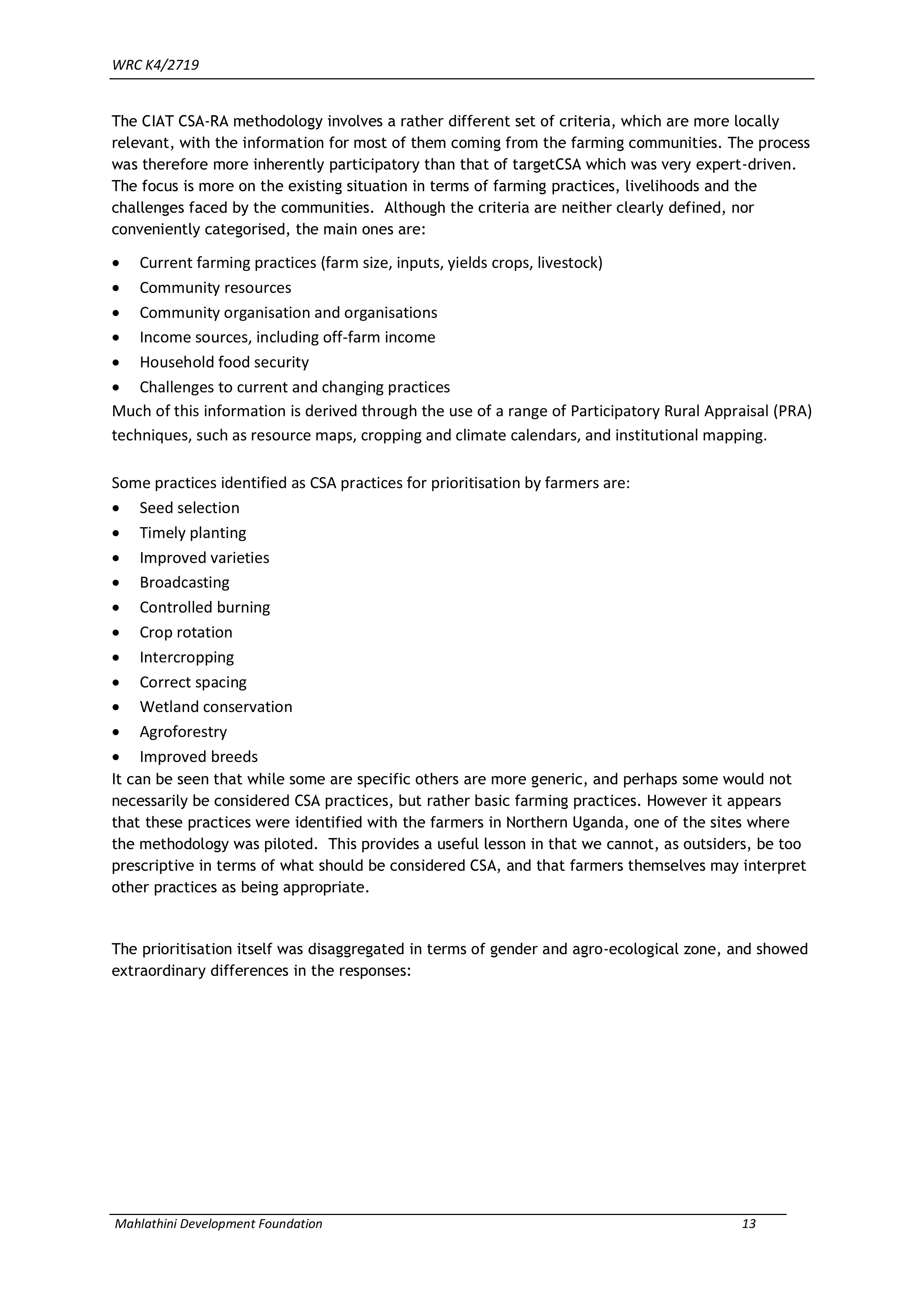

Improvement of water harvesting and water management

These show clearly that while improved soil management was important across almost the entire

country, it was particularly appropriate in some western, many southern central, and some eastern

areas. Improved water management is also appropriate across the country, but particularly vital in

the northern and eastern parts. When working at a local level, this DSS may help focus attention on

those specific interventions and practices most allied to the broad requirements identified by the

DSS for any particular area.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 13

The CIAT CSA-RA methodology involves a rather different set of criteria, which are more locally

relevant, with the information for most of them coming from the farming communities. The process

was therefore more inherently participatory than that of targetCSA which was very expert-driven.

The focus is more on the existing situation in terms of farmingpractices, livelihoods and the

challenges faced by the communities. Although the criteria are neither clearly defined, nor

conveniently categorised, the main ones are:

•Current farming practices (farm size, inputs, yields crops, livestock)

•Community resources

•Community organisation and organisations

•Income sources, including off-farm income

•Household food security

•Challenges to current and changing practices

Much of this information is derived through the use of a range of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

techniques, such as resource maps, cropping and climate calendars, and institutional mapping.

Some practices identified as CSA practices for prioritisation by farmers are:

•Seed selection

•Timely planting

•Improved varieties

•Broadcasting

•Controlled burning

•Crop rotation

•Intercropping

•Correct spacing

•Wetland conservation

•Agroforestry

•Improved breeds

It can be seen that while some are specific others are more generic, and perhaps some would not

necessarily be considered CSA practices, but rather basic farming practices. However it appears

that these practices were identified with the farmers in Northern Uganda, one of the sites where

the methodology was piloted. This provides a useful lesson in that we cannot, as outsiders, be too

prescriptive in terms of what should be considered CSA, and that farmers themselves may interpret

other practices as being appropriate.

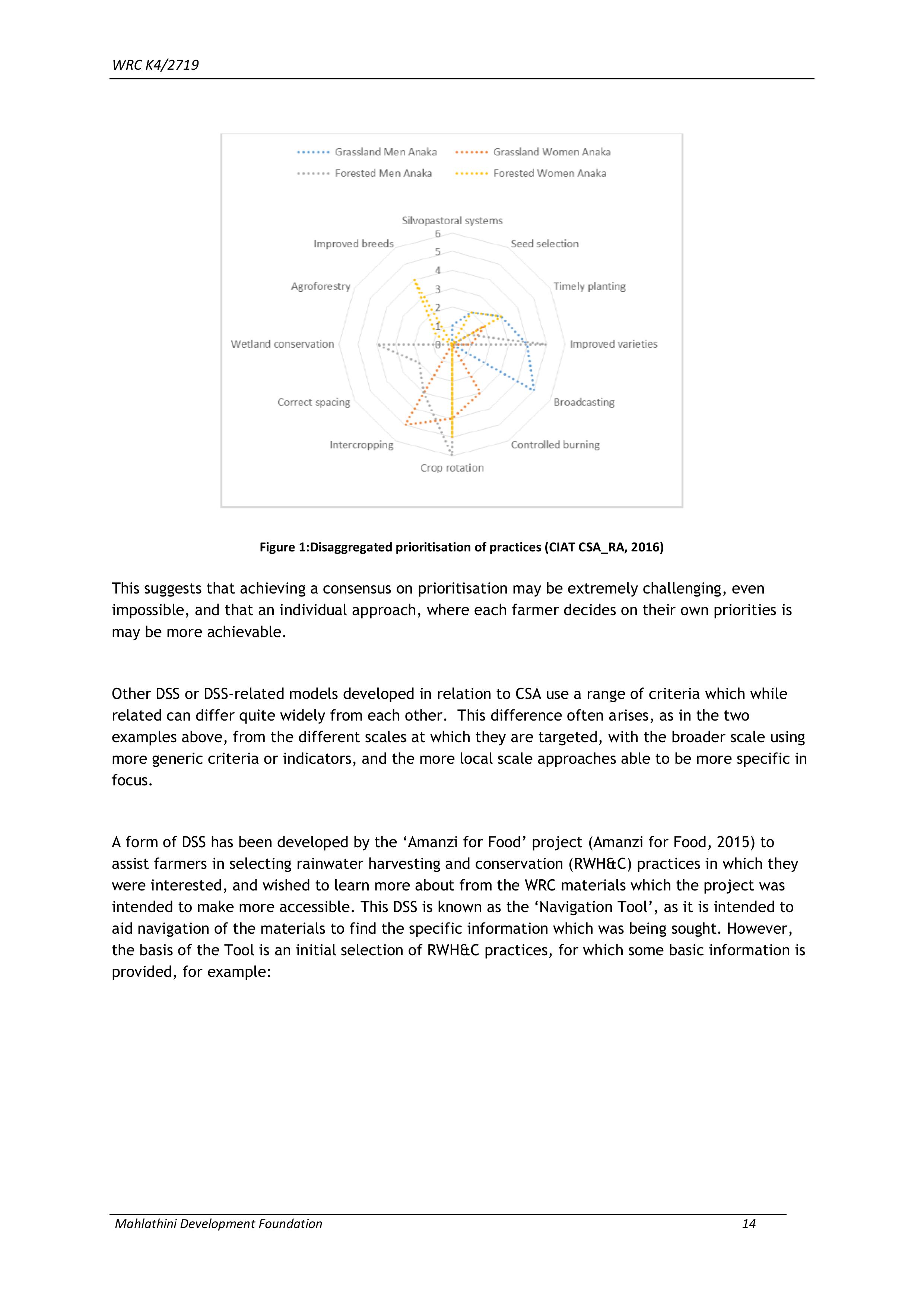

The prioritisation itself was disaggregated in terms of gender and agro-ecological zone, and showed

extraordinary differences in the responses:

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 14

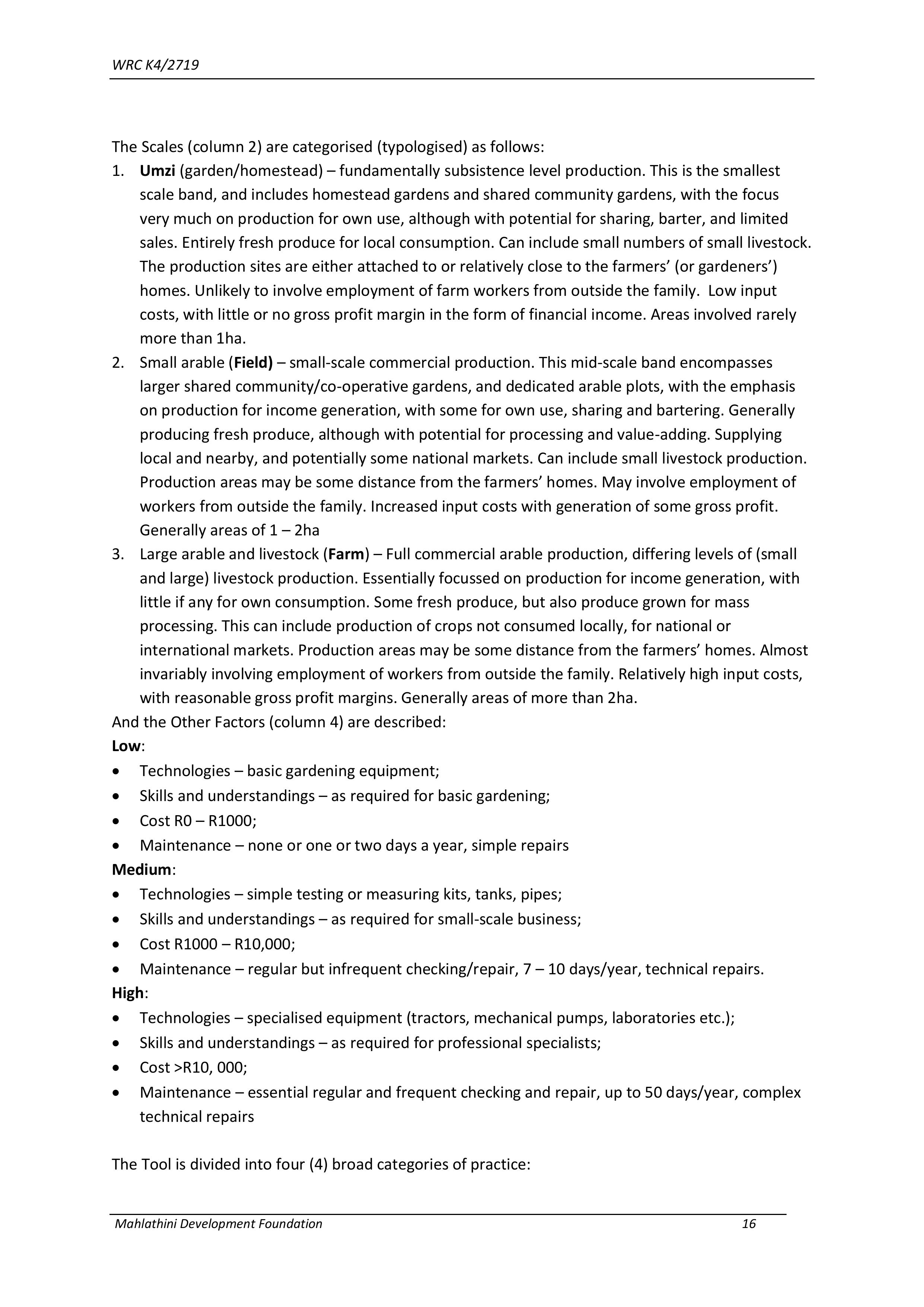

Figure 1:Disaggregated prioritisation of practices (CIAT CSA_RA, 2016)

This suggests that achieving a consensus on prioritisation may be extremely challenging, even

impossible, and that an individual approach, where each farmer decides on their own priorities is

may be more achievable.

Other DSS or DSS-related models developed in relation to CSA use a range of criteria which while

related can differ quite widely from each other. This difference often arises, as in the two

examples above, from the different scales at which they are targeted, with the broader scale using

more generic criteria or indicators, and the more local scale approaches able to be more specific in

focus.

A form of DSS has been developed by the ‘Amanzi for Food’ project (Amanzi for Food, 2015) to

assist farmers in selecting rainwater harvesting and conservation (RWH&C) practices in which they

were interested, and wished to learn more about from the WRC materials which the project was

intended to make more accessible. This DSS is known as the ‘Navigation Tool’, as it is intended to

aid navigation of the materials to find the specific information which was being sought. However,

the basis of the Tool is an initial selection of RWH&C practices, for which some basic information is

provided, for example:

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 15

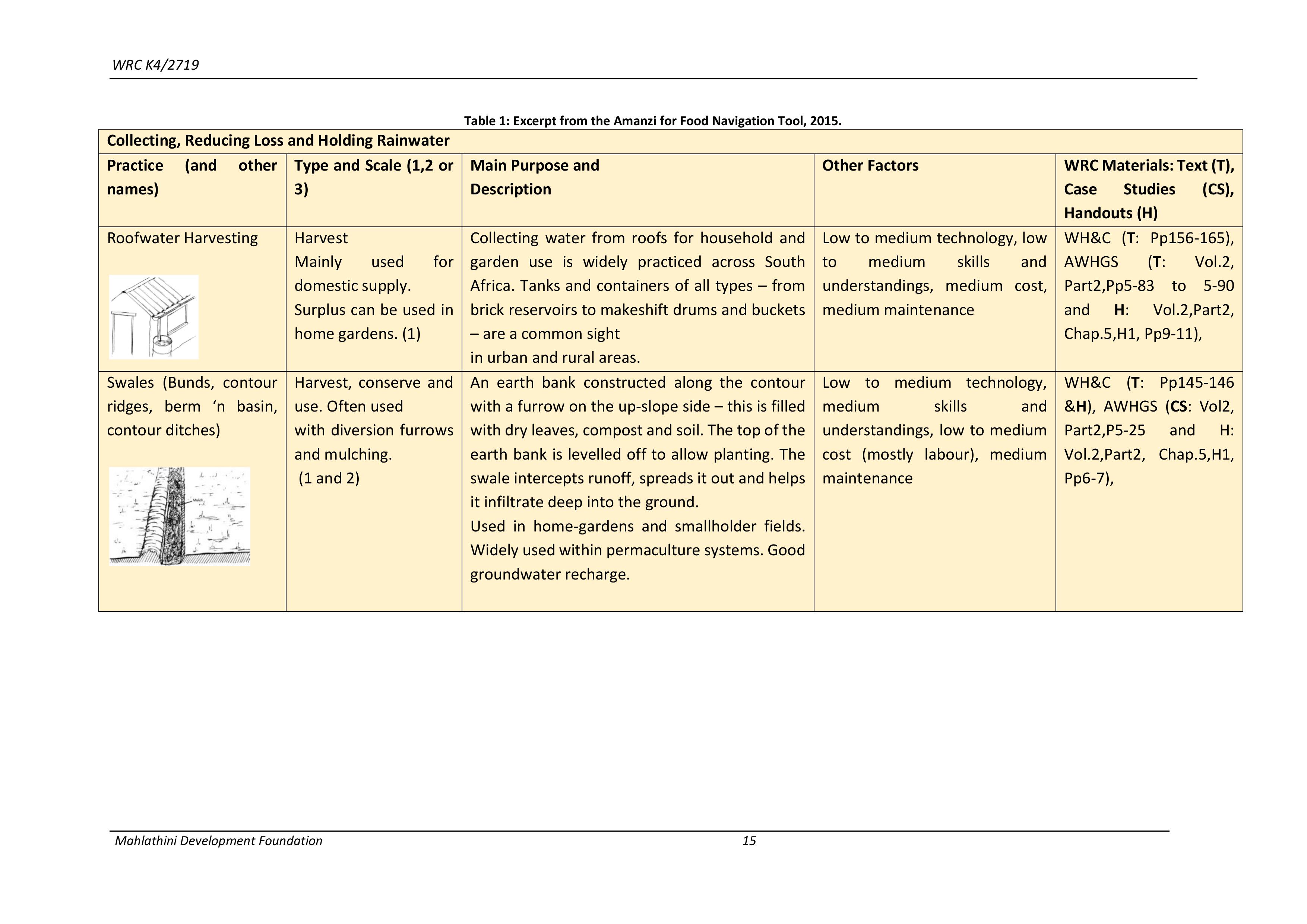

Table 1: Excerpt from the Amanzi for Food Navigation Tool, 2015.

Collecting, Reducing Loss and Holding Rainwater

Practice (and other

names)

Type and Scale (1,2 or

3)

Main Purpose and

Description

Other Factors

WRC Materials: Text (T),

Case Studies (CS),

Handouts (H)

Roofwater Harvesting

Harvest

Mainly used for

domestic supply.

Surplus can be used in

home gardens. (1)

Collecting water from roofs for household and

garden use is widely practiced across South

Africa. Tanks and containers of all types –from

brick reservoirs to makeshift drums and buckets

–are a common sight

in urban and rural areas.

Low to medium technology, low

to medium skillsand

understandings, medium cost,

medium maintenance

WH&C (T: Pp156-165),

AWHGS (T: Vol.2,

Part2,Pp5-83 to 5-90

and H: Vol.2,Part2,

Chap.5,H1, Pp9-11),

Swales (Bunds, contour

ridges, berm ‘n basin,

contour ditches)

Harvest, conserve and

use. Often used

with diversion furrows

and mulching.

(1 and 2)

An earth bank constructed along the contour

with a furrow on the up-slope side –this is filled

with dry leaves, compost and soil. The top of the

earth bank is levelled off to allow planting. The

swale intercepts runoff, spreads it out and helps

it infiltrate deep into the ground.

Used in home-gardens and smallholder fields.

Widely used within permaculture systems. Good

groundwater recharge.

Low to medium technology,

medium skills and

understandings, low to medium

cost (mostly labour), medium

maintenance

WH&C (T: Pp145-146

&H), AWHGS (CS: Vol2,

Part2,P5-25 and H:

Vol.2,Part2, Chap.5,H1,

Pp6-7),

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 16

The Scales (column 2) are categorised (typologised) as follows:

1. Umzi (garden/homestead) –fundamentally subsistence level production. This is the smallest

scale band, and includes homestead gardens and shared community gardens, with the focus

very much on production for own use, although with potential for sharing, barter, and limited

sales. Entirely fresh produce for local consumption. Can include small numbers of small livestock.

The production sites are either attached to or relatively close to the farmers’ (or gardeners’)

homes. Unlikely to involve employment of farm workers from outside the family. Low input

costs, with little or no gross profit margin in the form of financial income. Areas involved rarely

more than 1ha.

2. Small arable (Field) –small-scale commercial production. This mid-scale band encompasses

larger shared community/co-operative gardens, and dedicated arable plots, with the emphasis

on production for income generation, with some for own use, sharing and bartering. Generally

producing fresh produce, although with potential for processing and value-adding. Supplying

local and nearby, and potentially some national markets. Can include small livestock production.

Production areas may be some distance from the farmers’ homes. May involve employment of

workers from outside the family. Increased input costs with generation of some gross profit.

Generally areas of 1 –2ha

3. Large arable and livestock (Farm) –Full commercial arable production, differing levels of (small

and large) livestock production. Essentially focussed on production for income generation, with

little if any for own consumption. Some fresh produce, but also produce grown for mass

processing. This can include production of crops not consumed locally, for national or

international markets. Production areas may be some distance from the farmers’ homes. Almost

invariably involving employment of workers from outside the family. Relatively high input costs,

with reasonable gross profit margins. Generally areas of more than 2ha.

And the Other Factors (column 4) are described:

Low:

•Technologies –basic gardening equipment;

•Skills and understandings –as required for basic gardening;

•Cost R0 –R1000;

•Maintenance –none or one or two days a year, simple repairs

Medium:

•Technologies –simple testing or measuring kits, tanks, pipes;

•Skills and understandings –as required for small-scale business;

•Cost R1000 –R10,000;

•Maintenance –regular but infrequent checking/repair, 7 –10 days/year, technical repairs.

High:

•Technologies –specialised equipment (tractors, mechanical pumps, laboratories etc.);

•Skills and understandings –as required for professional specialists;

•Cost >R10, 000;

•Maintenance –essential regular and frequent checking and repair, up to 50 days/year, complex

technical repairs

The Tool is divided into four (4) broad categories of practice:

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 17

•General Skills, applicable to and underpinning many of the practices

•Collecting, reducing loss, and holding rainwater (as in example, above)

•Storing rainwater

•Using rainwater (irrigation)

Essentially here the criteria used for decision making are:

•Category of practice

•Type of practice

•Scale of farming operation

•Required technologies

•Required skills and understandings

•Cost

•Maintenance requirements

These do not include any bio-geographic or climate criteria, as most RWH&C practices are

considered appropriate in most except the very wettest (maybe not necessary) or very driest

(probably not realistic) areas. The aim is for farmers themselves to be able decide on the practices in

which they are most interested, according to their own context and needs, without requiring any

external support, and then to access more information on these from the materials.

While this last example does not include some criteria which may be crucial for a CSA DSS, and the

farming typologies may differ from those adopted by the WRC-CSA project, the fact that this is

designed for use by very much the same types of farmers who are the focus of the CSA project

suggests that the simplicity and immediate accessibility of this model may provide a valuable guide

to a CSA DSS.

Process

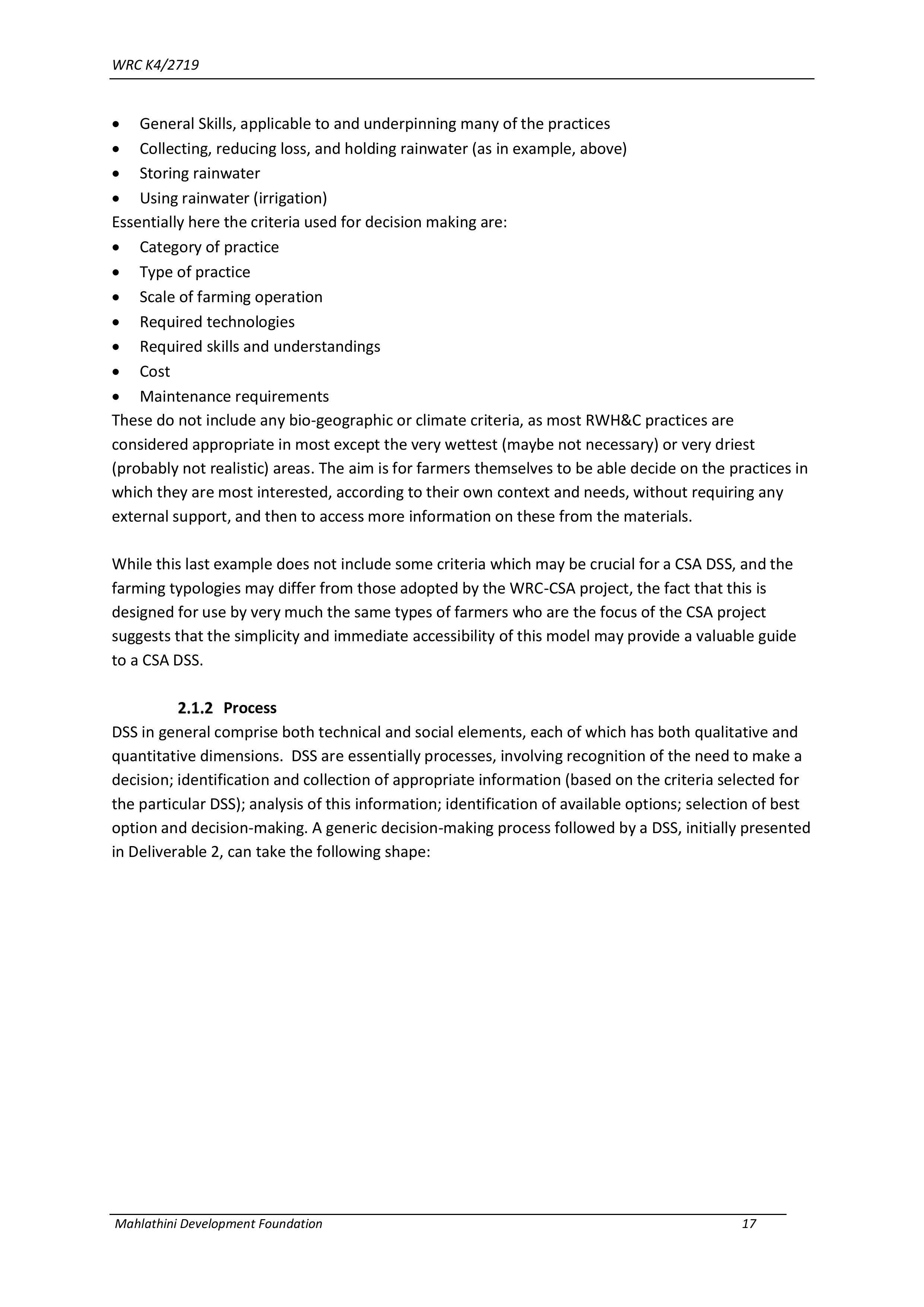

DSS in general comprise both technical and social elements, each of which has both qualitative and

quantitative dimensions. DSS are essentially processes, involving recognition of the need to make a

decision; identification and collection of appropriate information (based on the criteria selected for

the particular DSS); analysis of this information; identification of available options; selection of best

option and decision-making. A generic decision-making process followed by a DSS, initially presented

in Deliverable 2, can take the following shape:

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 18

Figure 2: decision making process (Adapted from Heinemann, 1988)

This suggests that while qualitative information, both technical (i.e. soil types, climate) and social

(i.e. availability of skills and resources) is essential for the process to be effective, this is not

necessarily the case for quantitative information (i.e. precise rainfall predictions, or specific market

requirements); indeed the latter may be extremely difficult to access.

One aspect of a decision-making process is the prioritisation of criteria, as those with the highest

priority may well provide the starting point for decision-making. For the targetCSA DSS, described

above, the clear priorities are climate predictions and soil types, the combination of which, in

concert with social criteria such as literacy level, according to the developers of this DSS determine

which practices might be most appropriate. The CIAS CSA-RA methodology is less clear about

prioritisation, and appears to leave this more to the farmers themselves, which is entirely

appropriate at the local level. The Amanzi for Food Navigation Tool, while not being prescriptive in

this respect does suggest that the scale of farming is quite a strong priority in terms of criteria, as

some practices , such as Saaidamme, are really only appropriate on a larger scale, while others, such

as mulching are most appropriate at the smaller scales. However, as with the CSA-RA approach, it is

the farmers themselves who mostly identify their own priorities in relation to the criteria.

Facilitation

An important tool in relation to understanding the social context within which farmers are operating

is a vulnerability assessment, for which a valuable toolkit is the CGIAR/CCAFS Working Paper 108:

Climate Change & Food Security Vulnerability Assessment Toolkit for assessing community-level

Yes

No

Implement decision

Select best alternative

Assess/analyse information

Identify options

Begin DSS process

Collect qualitative information

Decision needs to be made

Quantitative approach/information

needed?

Collect quantitative information

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 19

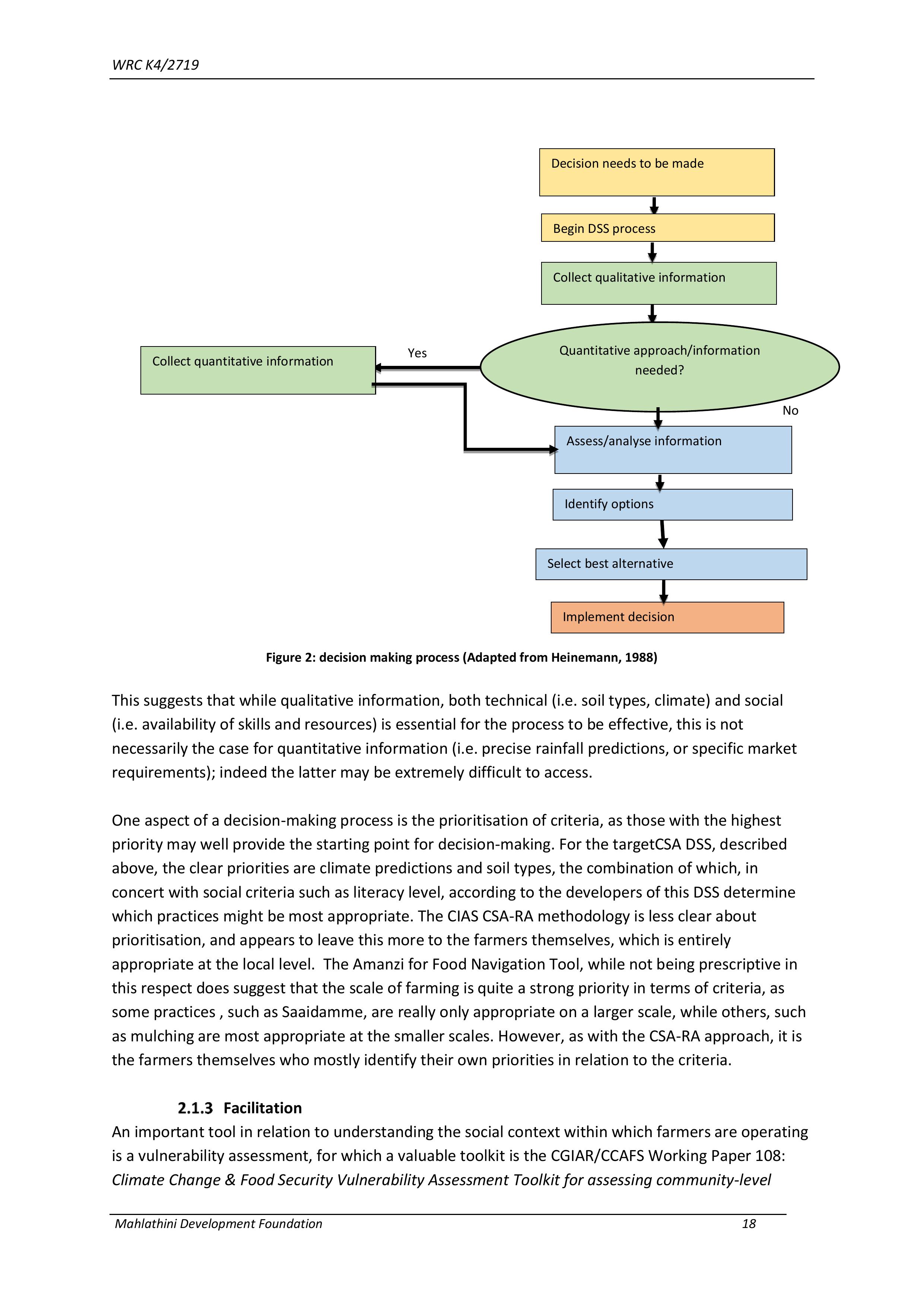

potential for adaptation to climate change(Ulrichs, Cannon, Newsham, Naess, & Marshall, 2015).

This toolkit, as discussed in Deliverable 2 is premised on 5 dimensions of vulnerability (DoV):

Figure 3: Dimensions of Vulnerability (CGIAR/CCAFS, 2015)

Such an assessment provides a strong foundation for determining the capacity of farmers for

adaptation. This approach has been adopted by different programmes globally, and is often

combined with a specialist, or external expert-driven process.

However, the broader aim of any facilitation in regard to the use of a DSS is to empower the farmers

to be confident in their decision-making with the support of the DSS. Any DSS at the local level must

be fully and easily accessible and useable by the farmers themselves with minimal facilitation long

after the project has finished. So while a facilitation process may begin with an analysis of

vulnerability, it must also, and very importantly, move to a recognition of opportunity and

developing farmers’ recognition of their own capacities to rise to challenges and grasp opportunities.

The Appreciative Inquiry approach of the Taos Institute, USA and the Voluntary Organisation for

Rural Development (VORD) in Bangladesh, takes very much this positive approach and their “…guide

on ‘Appreciative Inquiry to Promote Local Innovations among Farmers Adapting to Climate Change’

is prepared for the development workers who would like to facilitate a community learning and

adaptation process, especially for farmers in agriculture; facing challenges of climate change. This

guide is not about agricultural technologies which would help farmers to adapt but it is about

facilitating a process of sharing knowledge and technologies farmers are continuously innovating to

overcome challenges.” (Saya, 2012)

They define Appreciative Inquiry as:

“Ap-pre’ci-ate, v., 1. valuing; the act of recognizing the best in people or the world around us;

affirming past and present strengths, successes, and potentials; to perceive those things that give

life (health, vitality, excellence) to living systems. 2. to increase in value, e.g. the economy has

appreciated in value. Synonyms: VALUING, PRIZING, ESTEEMING, and HONORING.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 20

In-quire’ (kwir), v., 1. the act of exploration and discovery. 2. To ask questions; to be open to seeing

new potentials and possibilities. Synonyms: DISCOVERY, SEARCH, and SYSTEMATIC EXPLORATION,

STUDY.”

The process is promoted as a positive alternative to the problem-solving approach to development,

and is described as a 4D (Discovery, Dream, Design, Destiny) Cycle, centred on an Affirmative Topic.

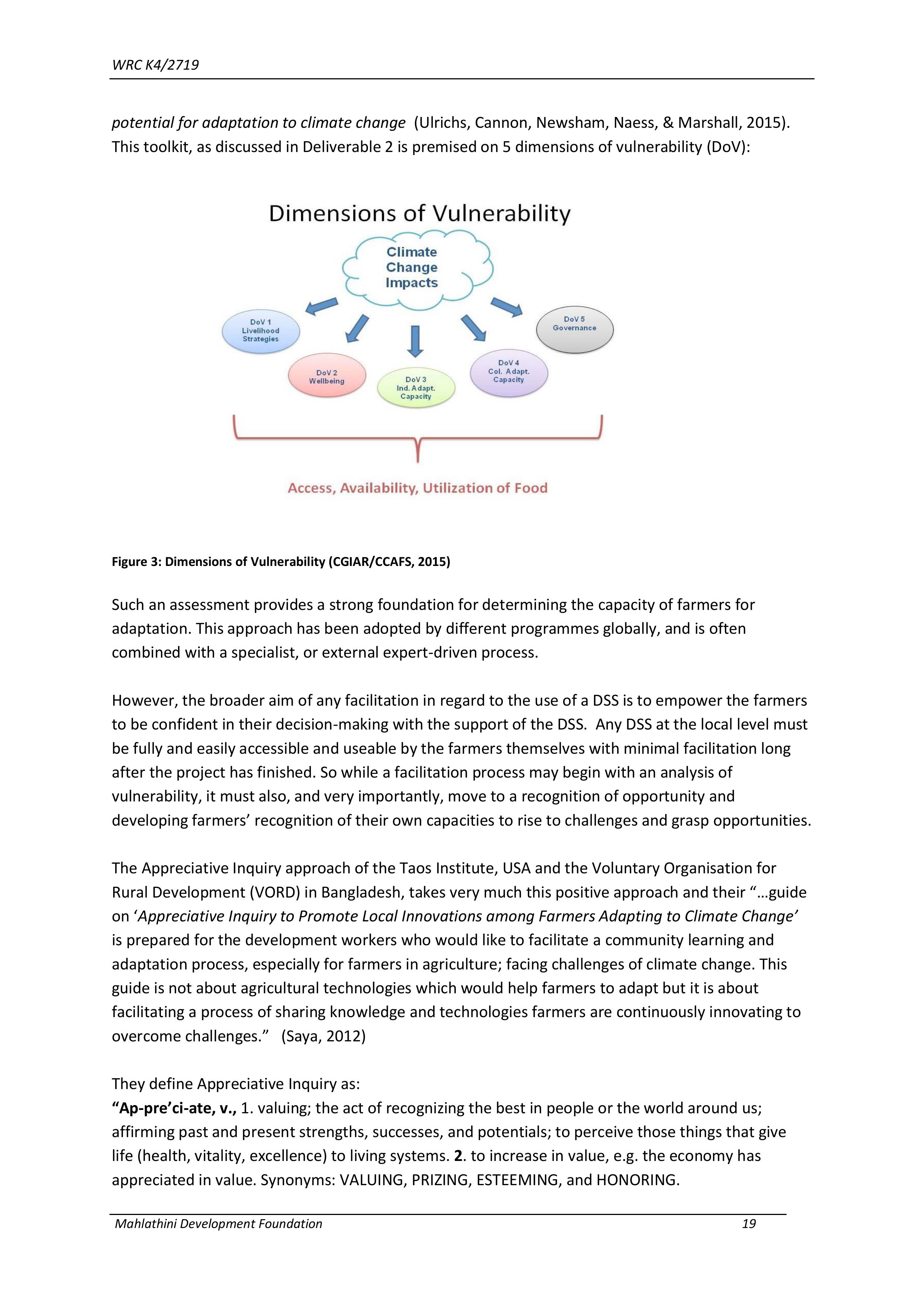

The Dialogues in Climate Change and Adaptation (DICLAD) process developed by the Association for

Water and Rural Development Resilm programme on the Oliphants River (AWARD, 2017), takes a

similar approach, which informs the following explorative process concerning climate change and

adaptation:

Figure 4: Schematic for DICLAD; Facilitating Understanding of Climate Change and Adaptation(AWARD, 2017)

The facilitation process appropriate for introducing the WRC-CSA DSS is described in Section 2 and 3

, below, and draws on the more participatory and positive approaches exemplified by the

Appreciative Inquiry and the DICLAD processes.

DSS for this project

The main aim of the DSS is for individual farmers or farming collectives to be capacitated to

strengthen their farming practices in the light of potential climate change impacts. A subsidiary aim

is to encourage farmers to support each other in this enterprise, and to encourage others, including

agricultural extension officers and personnel from local agricultural training institutions to also

support the process. Such support can be provided through the establishment of learning networks

as described later in Section 6.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 21

The WRC-CSA project DSS process follows a fundamentally participatory approach with emphasis on

farmers’ own experiences and understandings of climate change. Through a closely facilitated

process they identify trends, which they ascribe to climate change, which have impacted their

farming activities in recent years, and are encouraged to extrapolate from these to make predictions

about possible future impacts. In this they are supported by climate change and agricultural impact

predictions developed by the specialists. Following this there is an exploration of the farming

typologies in terms of scales of operation, the crops and livestock produced, and the specific

resources, natural and other, to which the farmers have access for their operations. Issues affecting

the natural resources are also explored.

These preliminaries lay the ground for discussion of what options are available to farmers to

improve their situation, particularly in the light of the predicted climate change impacts, and for the

introduction of a wide range of farming practices considered appropriate for increasing resilience in

the face of climate change. Based on their own understandings of their contexts, their skills,

knowledge and aspirations they can then select from the available practice options those they feel

are most appropriate and relevant to their situation. They can then besupported in the

implementation of these practices both by the facilitating organisation, initially the WRC-CSA team,

and indeed by other farmers and other members of their learning network.

At this stage in the project the idea is that the project team itself facilitates the DSS with the farmers

in the different areas, but the aim is, following extensive piloting of the process and the inevitable

refining that will follow, for the DSS to be developed as a complete package which can be facilitated

anywhere in the country by suitably skilled NGO or agricultural extension service personnel.

Decision Support System for CSA in smallholder farming systems

By Erna Kruger

The process of implementing the decision support system at farmer level is to follow the six steps

outlined below. Within each, there is a further process/ methodology for how this can be achieved.

Basically, the decision process moves from; Farmer typology AspirationsFarming systems

PracticesPrioritized practices for experimentation.

This is a cyclical review, planning and action process.

1. Climate change:

a. Hotter, drier

b. Rain variability, more intense

Summarise external information and baseline assessments: agro-ecological zones, climate

regimes (predictions, rainfall distribution, temperatures etc), socio-economic data social

issues, land use options (farming systems)

2. Issues, constraints, risks, vulnerabilities, aspirations/priorities

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 22

Community level climate change adaptation analysis

Farmer typologies (A,B,C)

Aspirations: Gardens, fields, livestock, trees

3. Potential adaptive measures and criteria for assessment

5 Categories of farming system (water, soil, crops, livestock, natural resources)

4. Practices

List of practices –filtered for farmer typology, aspiration, farming system

5. Prioritization of practices for farmer innovation

Ranking for implementation of farmer experimentation within existing practices using;

-Farmer criteria

-Biophysical and climate criteria(rainfall, temperature, topography, soil)

-

6. Monitoring, review, re-planning

Choice of visual (qualitative) and quantitative indicators for assessment by farmers and researchers

Assessment of adaptation and also impact

The diagram below summarises the above information

•Size

•Resources:physical,

environmental

•Resources: socio-

economic

•Social/institutional

•Management

capacity/technolog

y

Farmer

Typology: A,B,C

•Gardening

•Field cropping

•Livestock

•Trees, incl fruit

Aspiration

•Water

management

•Soil health

management

•Crop

management

•Livestock

management

•Natural resoruce

management

Farming system

•Water flow management

•Infiltration

•greywater management

•RWH

•Irrigaiton

•Soil erosion control

•Irrigation

•increased organic matter

•microclimate management

•crop diversification

(including varieties,

calendars

•improved tillage

•agroforestry

•fodder/feed management

•..........

Practices

•Labour

•Cost

•Ease- techincal

•Productivity

•Soil health

•Water use

efficiency

•Knowledge

Prioritzation -

criteria

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 23

Figure 5: The DSS for smallholder farming systems

Issues, constraints, risks and vulnerabilities

Community level climate change adaptation analysis

In these community level workshops -dialogues; facilitation tools are to be designed that can assist

in the analysis. These are to be carefully chosen to ensure an ability to differentiate between

weather and climate change, unpack changes in the environment and livelihoods and those affected

by climate change and impacts of these and current practices and adaptations already being

implemented to respond to these changes.

Facilitation steps proposed are as follows:

1. Contextualization: Natural resources, need to look at climate change databases for

KZN/EC/Limpopo, and discuss with people how these will affect them. Also look at the

difference between variability in weather and climate change. NB! There is variability in

weather and there is also a major change in that variability in weather, predictions and

certainty (Tools; impact picture, role plays,

2. Exploration of temperature and rainfall and participants’’ understanding of how these are

changing (Tool: Seasonal diagrams on temperature and rainfall –normal and how these are

changing)

3. Timeline in terms of agriculture (Tool: livelihoods and farming timelines -assessment of past,

present and future)

4. Reality Map: changes (in natural resources), impacts (of changes), practices (past, present,

future), challenges/responses (Tool: Mind mapping of impacts)

5. Current practices and responses (effectiveness of responses) (Tool: outlining adaptive

measures on mind map)

Using these facilitation steps a workshop process has been designed (and tested). Below is a

summary of the workshop outline:

1. What we are seeing around us, what has been happening (nature, economy, society, village,

livelihoods, farming) (list main issues (biophysical, social, economic) –with ranking of

vulnerability, organisational mapping, financial flows and services mapping,

2. Past, present, future of farming activities and livelihoods (timelines and trends)

3. Climate vs weather(role play)

4. Scientific understanding of climate change (Power point input)

5. Seasonality diagrams of temperature and rainfall –generally what it is, what is changing

(seasonality diagrams)

6. Reality maps (choose temp, or rainfall): draw up mind maps of impacts (mind mapping)

7. Turn impacts in to priority goals (positive statements) and think through adaptive measures

that we know of or think could work

8. Introduce a range of practices (facilitation team) related to these goals to broaden potential

adaptive measures(A4 picture summaries and power point presentations)

9. Walkabouts and individual interviews (transect walks, key informant interviews, mapping of

local innovations/adaptations)

10. Prioritization of practices –matrix using farmer level criteria for assessment (matrix ranking

and scoring)

11. Planning of farmer experimentation, learning sessions and implementation of practices

(Individual experimentation outlines, lists)

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 24

This process framework is explained in more detail in Section 3 below.

The facilitation process (Steps 1-10), have been piloted in four villages:

•2 in Limpopo (Tzaneen, Hoedpsruit): Sekororo (Lima RDF - Mahlathini), Turkey- Sedawa Ext

(AWARD-Mahlathini)

•2 in KZN midlands (Estcourt, Bergville): Thabamhlope (Lima RDF-Mahlathini), Thamela

(GrainSA-Mahlathini)

These villages were chosen so that 1 village in each province is already implementing food security

and some CSA practices and the other is new to the idea of considering climate change adaptation in

their farming.

Farmer typology

Individual interviews (10-20minimum), transect walks, household visits

Summarise and present in focus group discussions for review

Here farmers choose a category (A,B,C)within which they feel the most comfortable based on the

following criteria;

•Head of household (male/female)

•No of adults

•No of children

•Dependency ratio

•Income sources

•Level of income

•Scale of operation; 0,1-1ha, 1-2(5) ha, > 2 (5) ha

•Farming activities; Aspirations –gardens, fields, livestock,trees

•Market access

•Other activities

•Resources

•Water access

•Infrastructure

•Knowledge and skills

•Literacy rate/ level of schooling

•Social organisation

This process was initiated and a sample of household interviews conducted in the four villages

where the process has been piloted. From here the work will continue in fleshing out farmer

typologies that make sense to local participants.

Potential adaptive measures and criteria for assessment

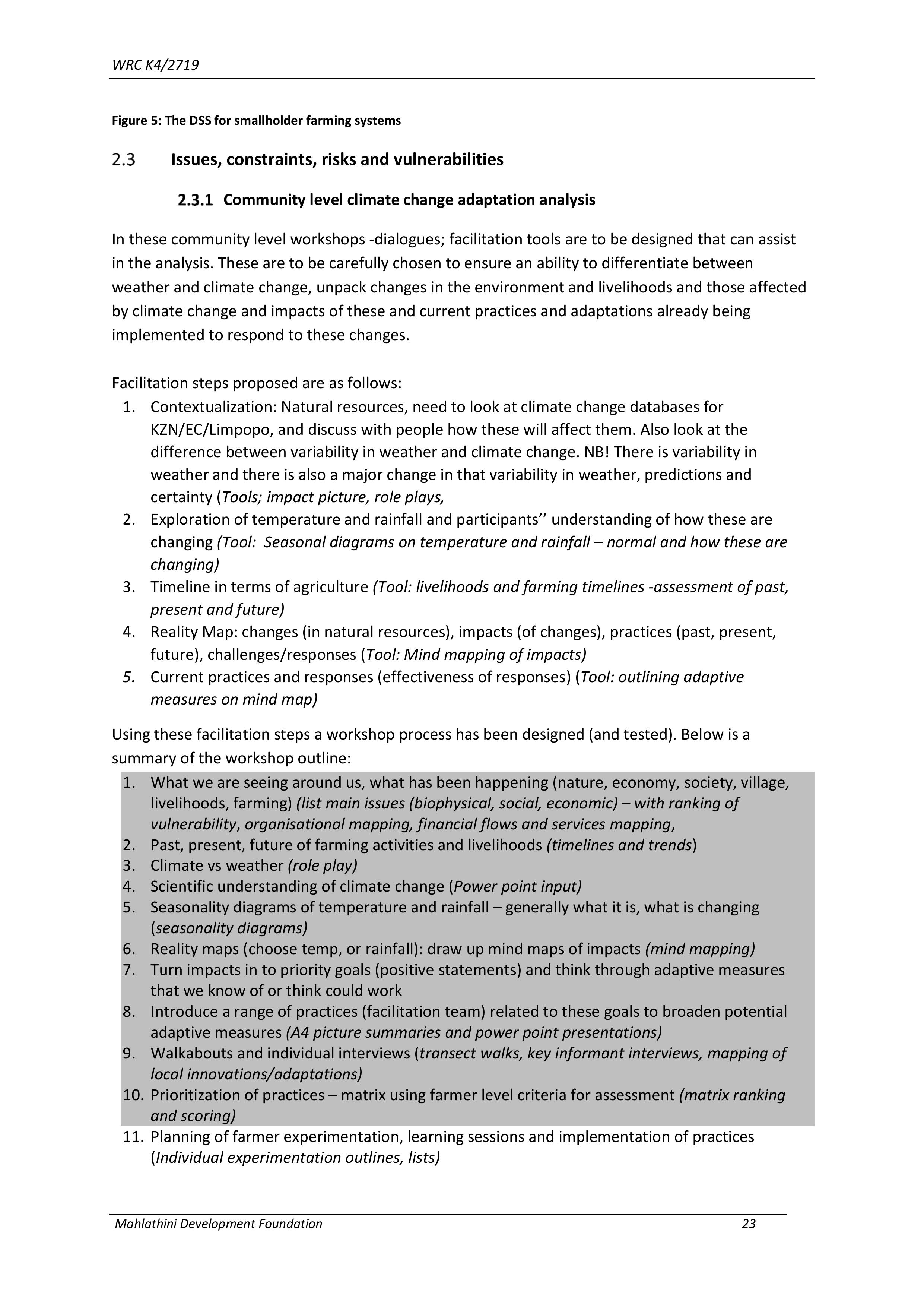

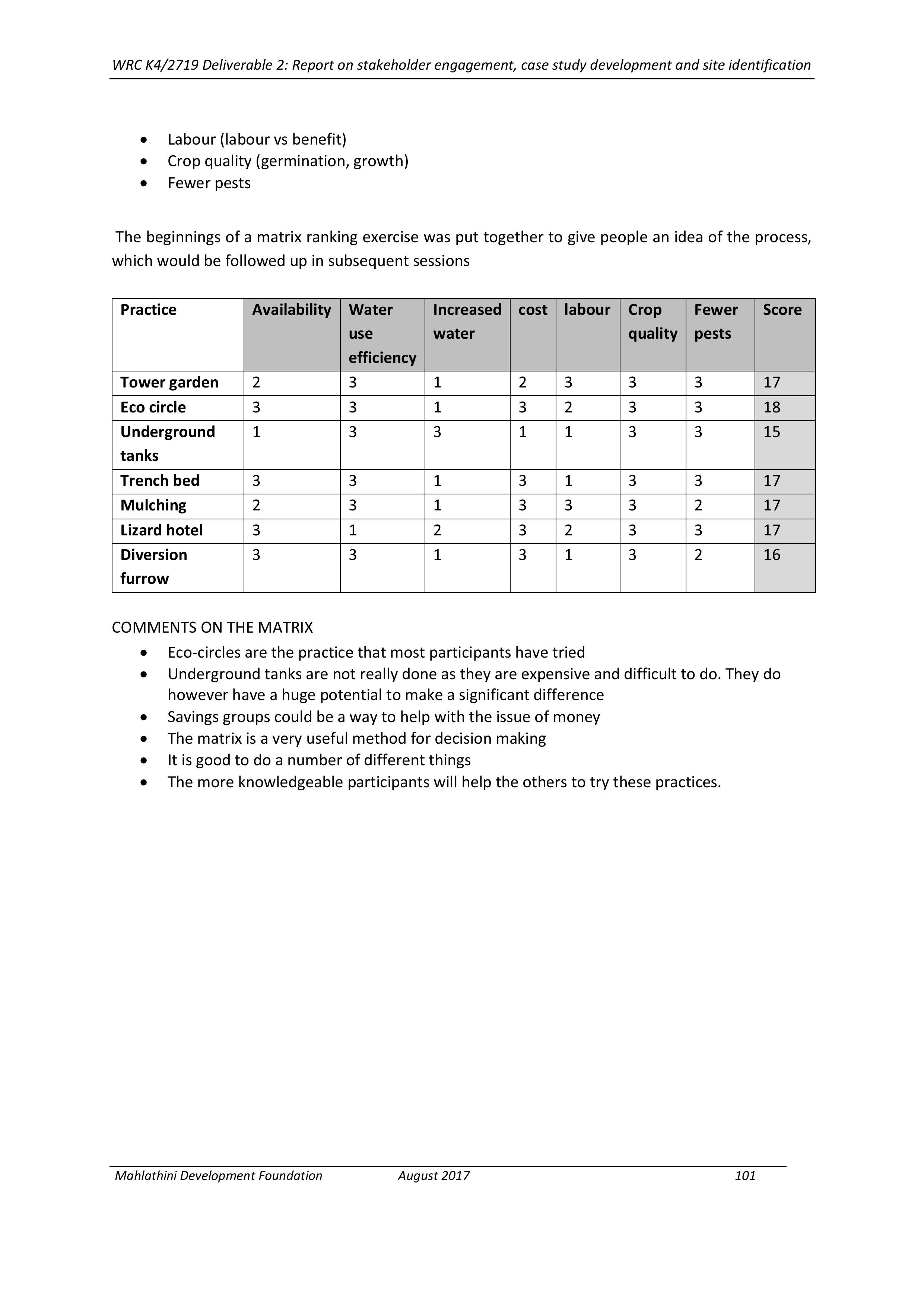

The matrix ranking exercise was conducted in two of the four pilot villages; the two villages where

food security implementation is already under way. The practices chosen by the groups were

assessed against the criteria using a simple scale of 1-3 where 1 is little/bad, 2 is medium or OK and

3 is good or a lot.

Below is a small table that compares the different criteria used by the participants in Limpopo and

KZN. As can be seen there are a number of criteria used by all three groups and across both

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 25

provinces; including increased water availability, increased water access, costs, increased crop

quality and labour requirements.

Table 2 :Community level criteria for assessment of CSA practices; Nov-Dec 2017

CRITERIA

Sekororo

Thabamhlophe(2 groups)

Increased water availability/ water use efficiency

Increased water access

Increased soil fertility

Costs

Increased crop quality

Labour

Time taken for implementing practice

Tools

Availability of materials

Fewer pests

From these exercises it will be possible to outline a number of criteria which are common across

different groups in different areas and work with these to fine tune categories of practices for the

DSS. Criteria will also differ slightly depending which sets of practices are being compared.

Practices chosen by participants(as shownin the photos below)included: tower gardens, keyhole

gardens, eco-circles, trench beds, mulching, intercropping, No -till (with planters and using hand

hoes), underground storage tanks, jo-jo- tanks, diversion furrows, furrows and ridges, tunnels,

lizard hotels (promotion of pest predators)

Clockwise fromtopleft: Sekororo matrix of

practices assessed against criteria and

matrices for 2 groups in Thabamhlophe.

For the two new villages, it did not make

sense to compare practices against each

other without participants knowing much

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 26

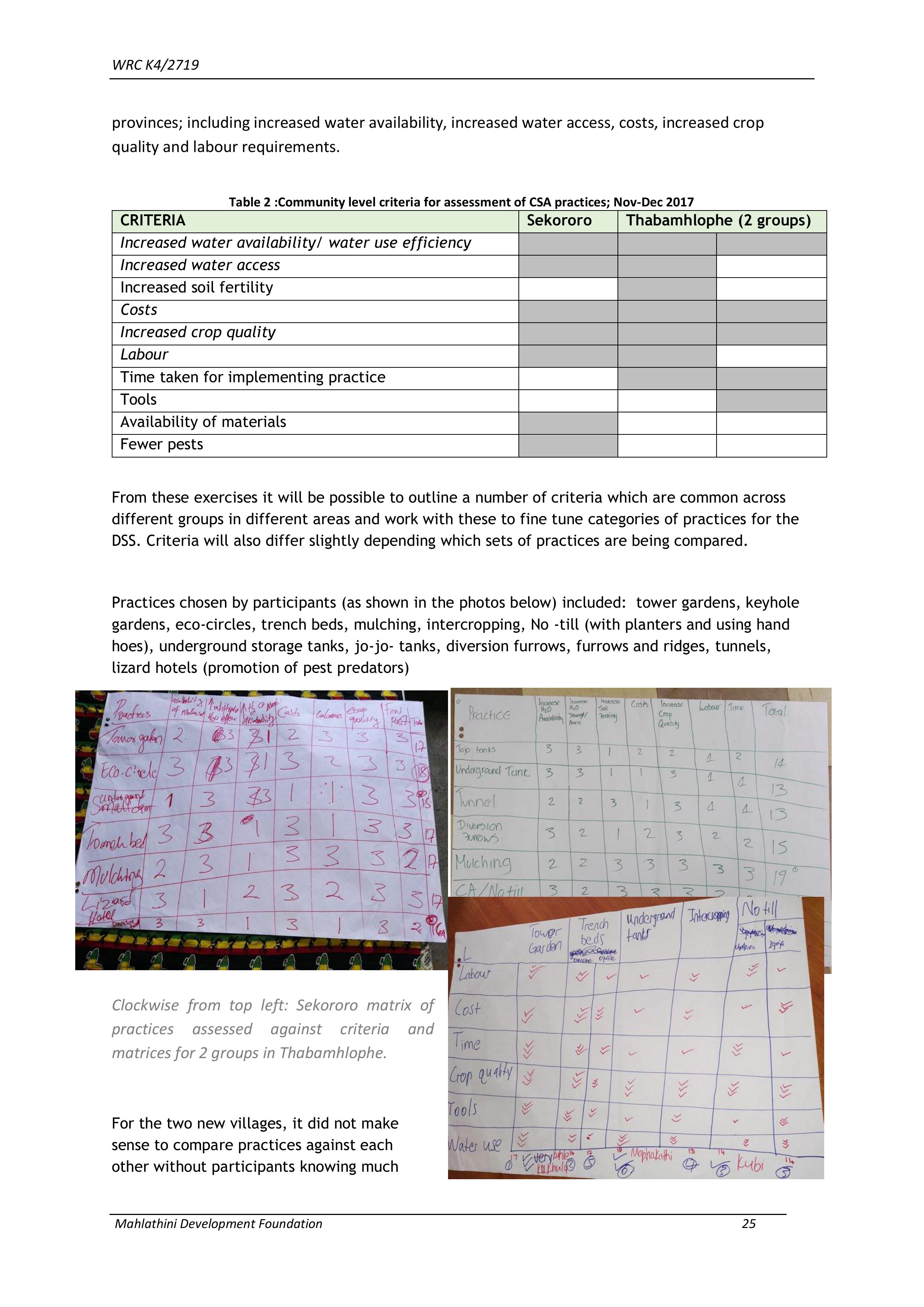

about them. Here a slightly different process to elucidate criteria for assessment from participants

would need to be designed. We tried out an exercise where participants did an assessment of

practices they are already aware of in the village and asked them whether it works and if not why

not to begin to tease out some of the criteria participants would use.

In Turkey for example the participants came up with the following analysis:

In this picture participants looked

at rainwater harvesting, sand

dams, cutting grass and storage

for fodder for livestock, tunnels

and planting indigenous trees in

their gardens for shade.

Criteria they used here to assess

how well these practices work in

the village were; costs versus

benefit, labour and safety.

Right: Picture of an analysis of

local climate adaptation measures

in Turkey (Hoedspruit, Limpopo,

Nov 2017)

This is an ongoing process and will be explored further in the next round of workshops.

Practices

The database of practices that has been developed throughout deliverables 1 and 2 has been

slightly expanded and tidied up.The inventory of practices has been updated and practices related

to livestock management have been given some attention, as it is clear already from our

interaction with communitiesthat this is going to be a more central theme than initially

anticipated. See Attachment: DSS Flowchart_20171218

Practices that have been suggested by participants which are not yet in the database (but will be

included) are:

-Windbreaks

-Spring protection

-Strip cropping

-Fodder production (dryland and irrigated) and

-Biogas digesters

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 27

An A4 summary of each practice with pictures and criteria. These can be presented initially as an

overview of options(related to what participants are prioritizing) and later used as the basis for

information provision in learning events. A few examples are shown below

The process of working with the facilitation team to choose a small selection 5-8 practices to

present to the participants in the workshop situation has worked well. Some form of prioritization

is required (this will eventually happen through the DSS), as all practices cannot presented all at

once to the group. These practices are based on the discussions on impacts and adaptive measures

done on the first day of the workshop.

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 28

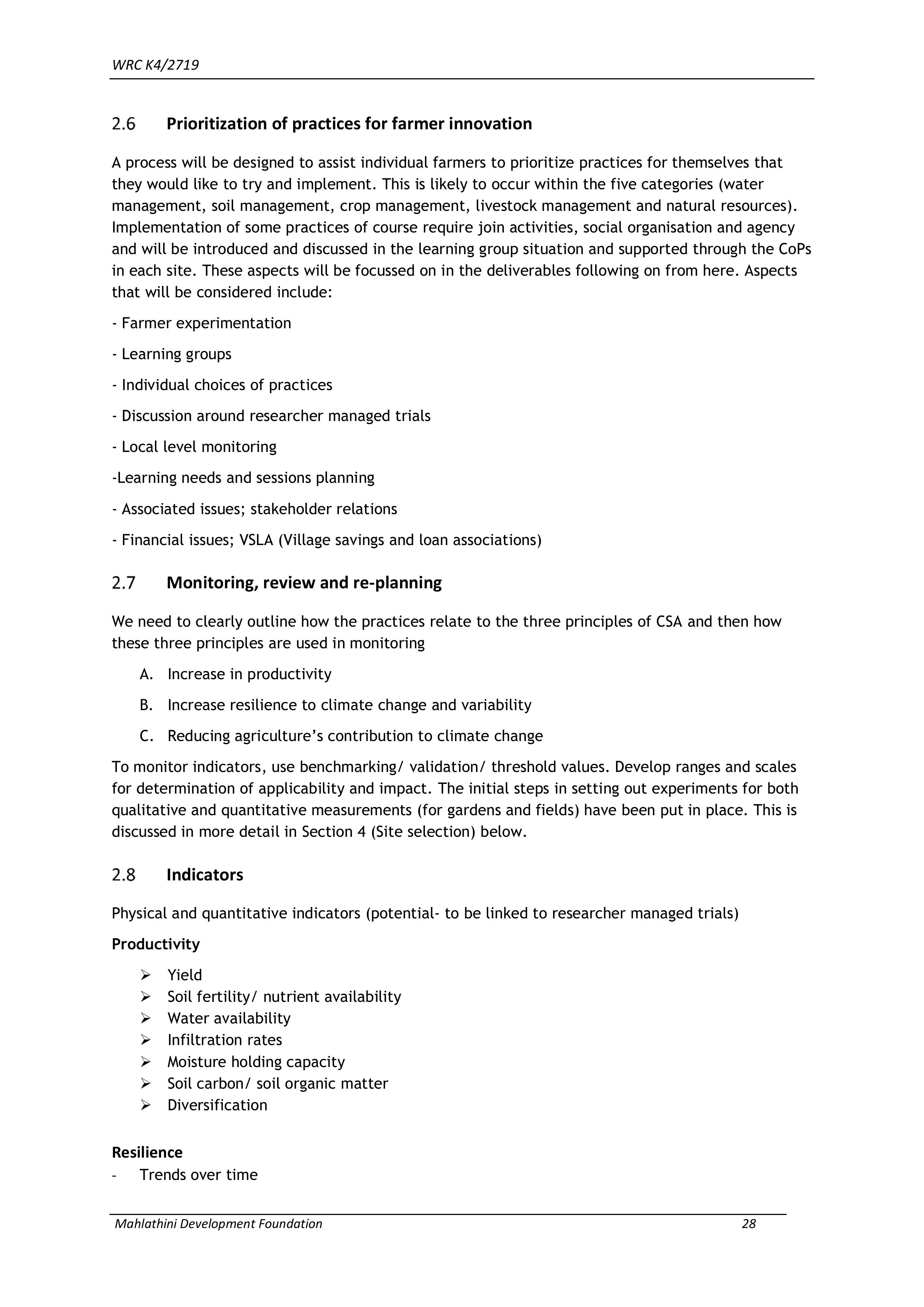

Prioritization of practices for farmer innovation

A process will be designed to assist individual farmers to prioritize practices for themselves that

they would like to try and implement. This is likely to occur within the five categories (water

management, soil management, crop management, livestock management and natural resources).

Implementation of some practices of course require join activities, social organisation and agency

and will be introduced and discussed in the learning group situation and supported through the CoPs

in each site. These aspects will be focussed on in the deliverables following on from here. Aspects

that will be considered include:

- Farmer experimentation

- Learning groups

- Individual choices of practices

- Discussion around researcher managed trials

- Local level monitoring

-Learning needs and sessions planning

- Associated issues; stakeholder relations

- Financial issues; VSLA (Village savings and loan associations)

Monitoring, review and re-planning

We need to clearly outline how the practices relate to the three principles of CSAand then how

these three principles are used in monitoring

A. Increase in productivity

B. Increase resilience to climate change and variability

C. Reducing agriculture’s contribution to climate change

To monitor indicators, use benchmarking/ validation/ threshold values. Develop ranges and scales

for determination of applicability and impact.The initial steps in setting out experiments for both

qualitative and quantitative measurements (for gardens and fields) have been put in place. This is

discussed in more detail in Section 4 (Site selection) below.

Indicators

Physical and quantitative indicators (potential- to belinked to researcher managed trials)

Productivity

➢Yield

➢Soil fertility/ nutrient availability

➢Water availability

➢Infiltration rates

➢Moisture holding capacity

➢Soil carbon/ soil organic matter

➢Diversification

Resilience

-Trends over time

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 29

-Diversity of practices

-Social agency

-Adaptability- awareness and response, system and farmer flexibility

-Robustness- soil health

-Reduced risk- reduced water demands

Carbon

-Soil management practices

-Crop and animal husbandry management

-Reduced carbon emissions-reduce mechanization, Extensive livestock production

-Increase carbon capture- reduction of veld burning, increase in SOM

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 30

3PROCESS FRAMEWORK

By Temakholo Mathebula

Climate Smart Agriculture: Process Facilitation

Introduction

The introduction of climate smart agriculture (CSA) requires a clear understanding of its suitability,

costs and benefits, and environmental implications in a local context. Hence, the approaches that

aim to identify and prioritize locally appropriate CSA practices will need to address the context

specific and multi-dimensional complexity in agricultural systems. When addressing complex

challenges that cannot be solved by formal research alone and for which various stakeholders are

required to identify solutions, more participatory and learning orientated approaches need to be

applied. Stimulating stakeholder participation (government, NGO’s, community members,

researchers, extension practitioners) in the different stages of research will result in more relevant

and effective solutions to challenges that will be addressed. Participation includes people’s

involvement in the decision making processes, program implementation, and information sharing as

well program evaluation. Participatory tools can be used to incorporate people’s ideas into

development plans and empower them to acquire skills and knowledge to make more informed

decisions. Incorporating participatory approaches will be of importance in the WRC CSA project as

it will allow for deeper understanding of the realities in the communities across the three

provinces, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), Limpopo and Eastern Cape (EC) and thus the identification of

relevant and context specific practices.

Process Facilitation

The initial phase of implementation of the WRC CSA project will include a study of climate change

databases for KZN, EC and Limpopo to gain an understanding of the change in rainfall patterns and

temperatures in the three provinces, which will be discussed with participants. Participatory Rural

Appraisal (PRA) and Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) tools will be used in the contextualization of the

realities and issues relating to climate change, local resources, farming practices and socio-

economic status. The PRA/RRA tools to be used include a focus group discussion, community

resource map, seasonal calendar, historical timeline, village walk and the ranking matrix. The

expected outcome will be a greater understanding of farmer perceptions towards climate change,

current practices and responses, prioritization of issues and the identification of the most relevant

practices.

The process facilitation will be conducted over a period of two days. The first day will commence

with a focus group discussion on climate change, its impacts and farmer responses to changes. The

focus group will be followed by a group exercise of community resource mapping with the objective

of graphically presenting the access to, control and distribution of resources. The third tool is a

seasonal calendar of farming activities, depicting seasonal variations and periods of vulnerability.

Lastly, a historical timeline will be used to depict changes in crop production over time and the

factors driving these changes.

Day 1

Focus Group Discussion

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 31

A focus group discussion consists of people with similar concerns, share a common problem and

purpose. It is used to obtain information that would not be expressed in a larger setting and the

advantages of this tool are that a lot of information can be collected in a short space of time, the

information gathered is grounded in the local setting, different views and perspectives are shared

on one platform and sensitization and awareness raising to decision making on specific topics. The

focus group discussion will seek toanswer the following:

-What are the farmers’ current understanding of climate change?

-Do farmers know the difference between climate change and weather variability?

-What does research say about climate change in their local context?

-What practices are they currently using?

-How effective are their current practices in mitigating the effects of climate change?

-What do the farmers foresee happening in the future based on what they are currently doing?

-What are their biggest challenges and who do they think can assist in addressing those

challenges?

The focus group discussion will serve to give background information on existing paradigms

regarding climate change and will allow for exploration and cross checking of different views.

Community Resource Map

A Community Resource Map is used to depict the occurrence, spatial distribution access to and

utilization of resources. The group will draw a map showing rivers, forests, livelihoods, households

and infrastructure and will include information they find relevant starting from a main reference

point. The facilitator will not intervene once the drawing has begun as the purpose of this exercise

will be for participants to depict their current situation as they see and perceive it. The map will

be used for further analysis during the transect walk to help gain an understanding of how the

participants picture their situation compared to what is actually taking place. The outcome of

resource mapping will be to identify local resources and strengths within the community.

Table 3: Community resource map description and uses

Name of Tool

Community Resource Map

Description

Depicts information regarding the occurrence, distribution, access to and

distribution of resources from the perspective of the participants

Uses

To identify links between resources, landmarks, households and activities

Allows people to picture their resources and show their significance through

drawing

Identify resources, challenges and opportunities

Information

gathered

Graphical presentation of how people view their environment, participants’

analysis of their natural environment

Complementary

tools

Transect walk, seasonal calendar

Time

1.5 to 2 hours

Seasonal Calendar

A seasonal calendar reflects the participants’ concept of time and seasonal categories. The tool is

useful in identifying main crops, planting sequences and the associated activities. It also allows for

a plenary discussion regarding access to and control of resources between men and women and how

gender roles impact uptake of practices. A period of a year is covered using a seasonal calendar,

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 32

but ideally a longer period of up to 18 months or more will give the full seasonal variations.

Symbols can be used to show the different seasons. The facilitator will ask which phenomena

(production, climate, social, economic, resource distribution etc.) fluctuate on a seasonal basis and

these will be listed. Priority will be given to aspects which are clearly linked to the mainfocus of

the research.

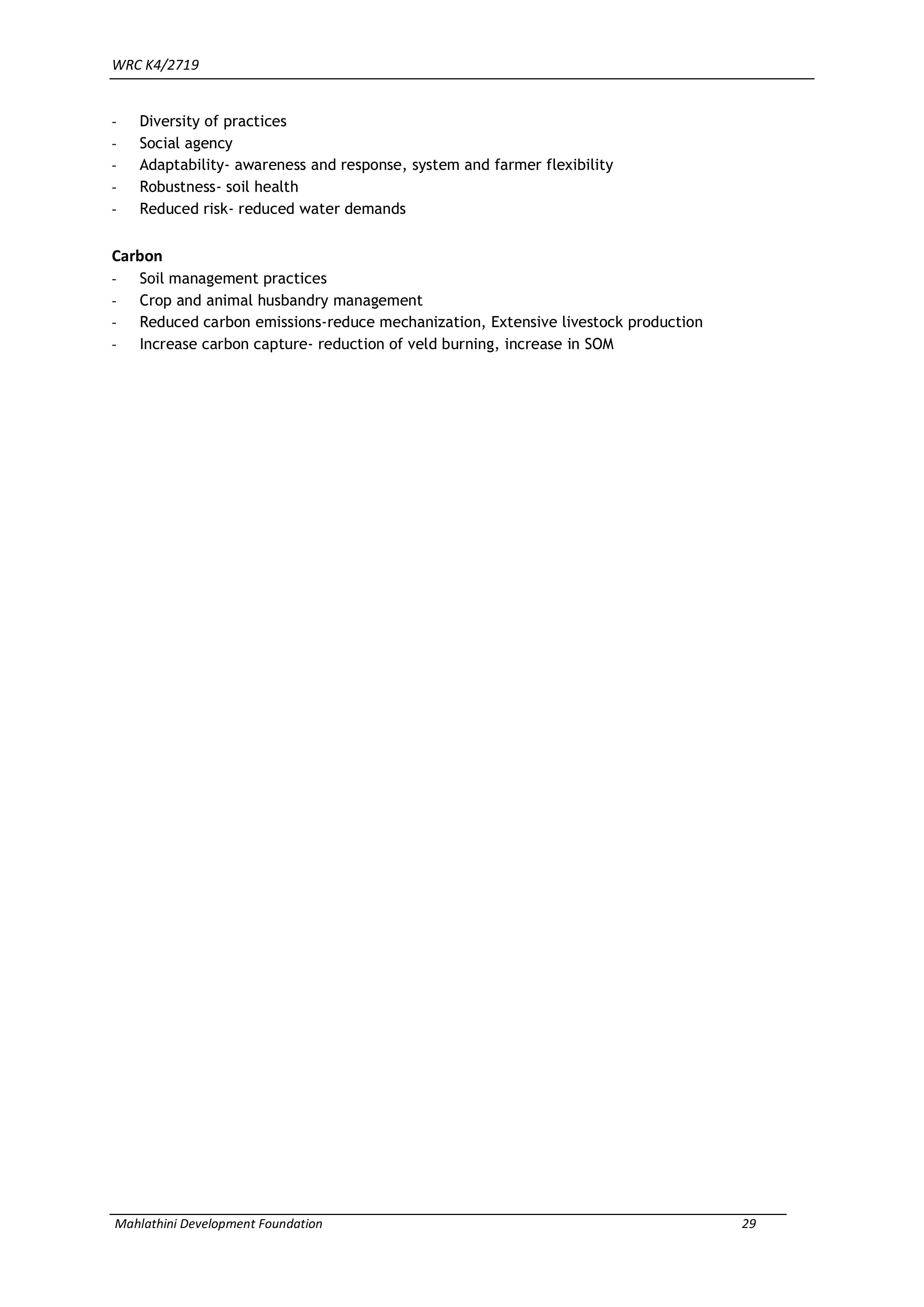

Table 4: Seasonal calendar description and uses

Name of Tool

Seasonal Calendar

Description

Visual method of showing the distribution of seasonally varying

phenomena related to and influencing production

Uses

Gives insights into seasonal differences

Highlights cause-and-effect relationships between seasonally varying

phenomena

Identify periods of the season where social groups are more or less

vulnerable

Identify coping and mitigation strategies used by participants to

minimize risk

Information gathered

Seasonal variations in vulnerability, control of and access to resources,

activities

Complementary tool

Ranking Matrix

Time

1.5 to 2 hours

Table 5:Seasonal calendar

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sept

Oct

Nov

Dec

Temperature

and Rainfall

Crops

Livestock

Income and

expenditure

Social

activities

Illness and

diseases

Employment

Historical Timeline

The historical timeline gives insight into specific changes over an extended period of time. The

advantage of using this tool is that it links different issues in time, and helps participants identify

significant changes in agricultural production over time. The timeline should return to the most

distant point in time or as far as participants can remember as a starting point. Events are placed

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 33

in a vertical line that represent the timeline with the oldest event placed at the top. When the

timeline is concluded, trends and important events will be discussed, i.e. changes in crop varieties,

weather conditions, significant changes in yields and other important factors.

Day 2

Village Walk

The village walk is a walkabout with the aim to raise participants’ awareness on the spatial

distribution of agricultural resources and their management. A transect diagram depicting soil,

topography, water access and natural resources is drawn up with their different uses and

variations, associated challenges and opportunities. The walkabout is conducted along the largest

diversity of areas and land uses. Questions to be answered during this activity are:

-Which resources are present (land uses, vegetation, crops)?

-Why are these resources present?

-How is labour distributed and who benefits from these resources?

-What changes have the participants observed in the past?

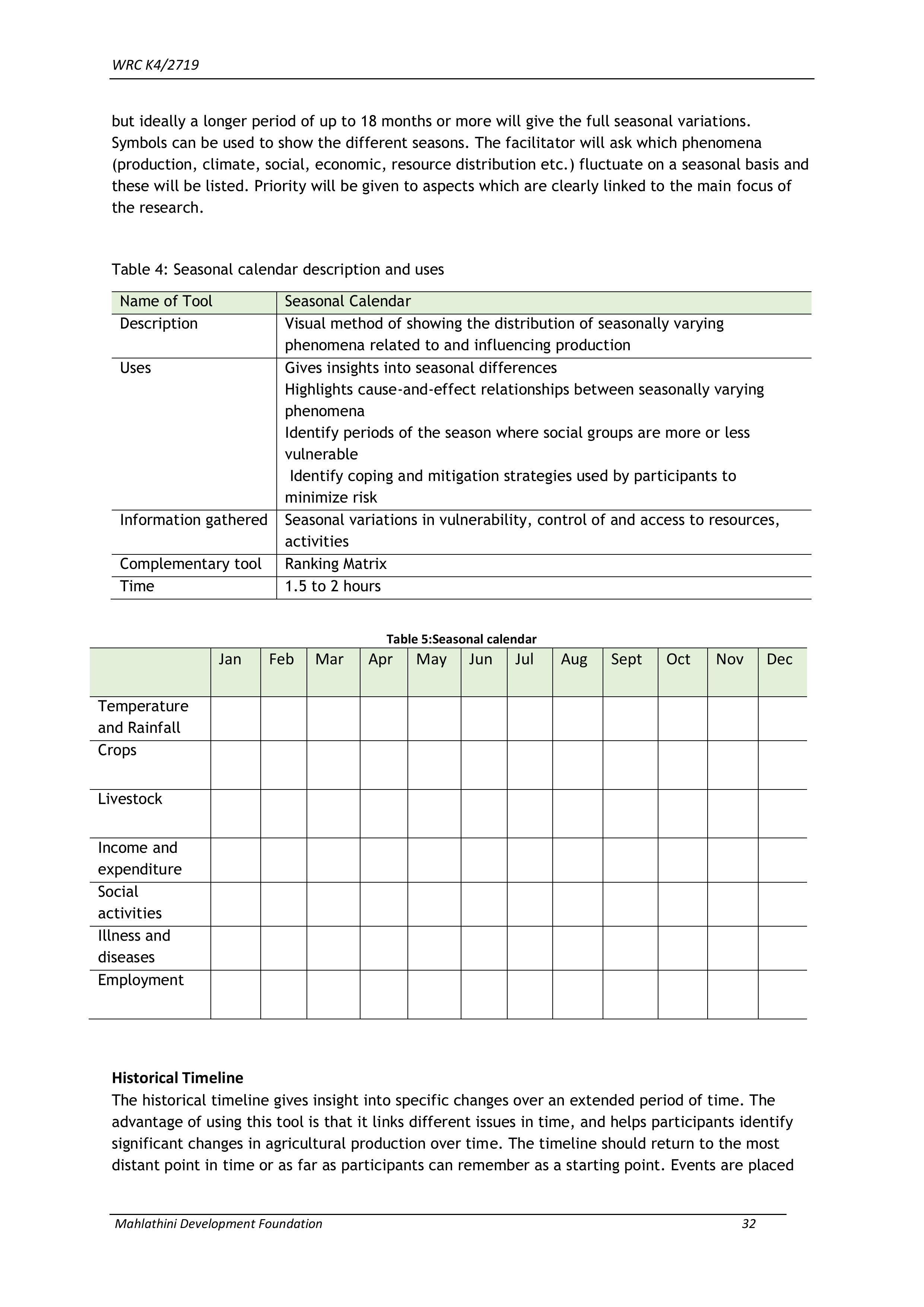

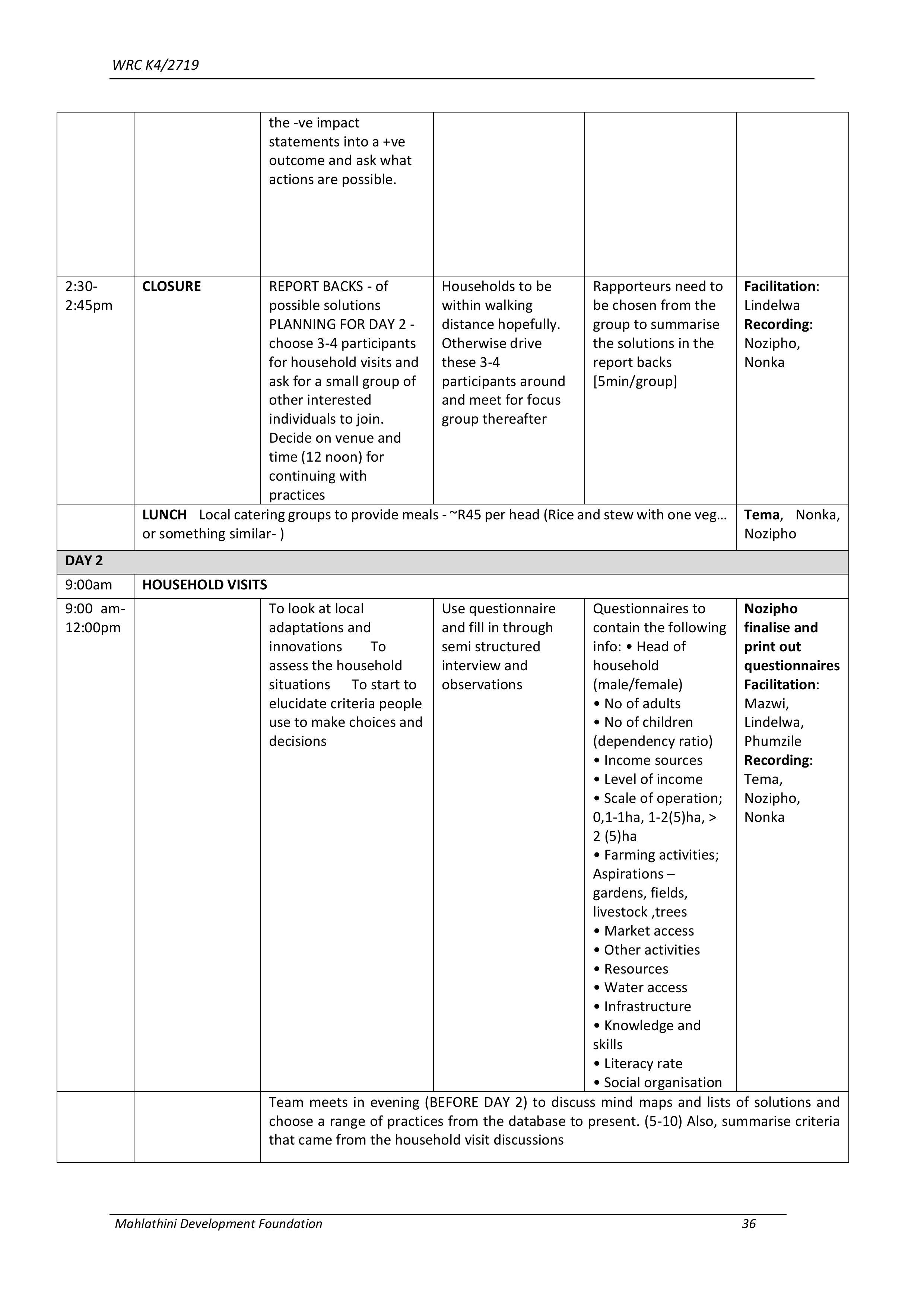

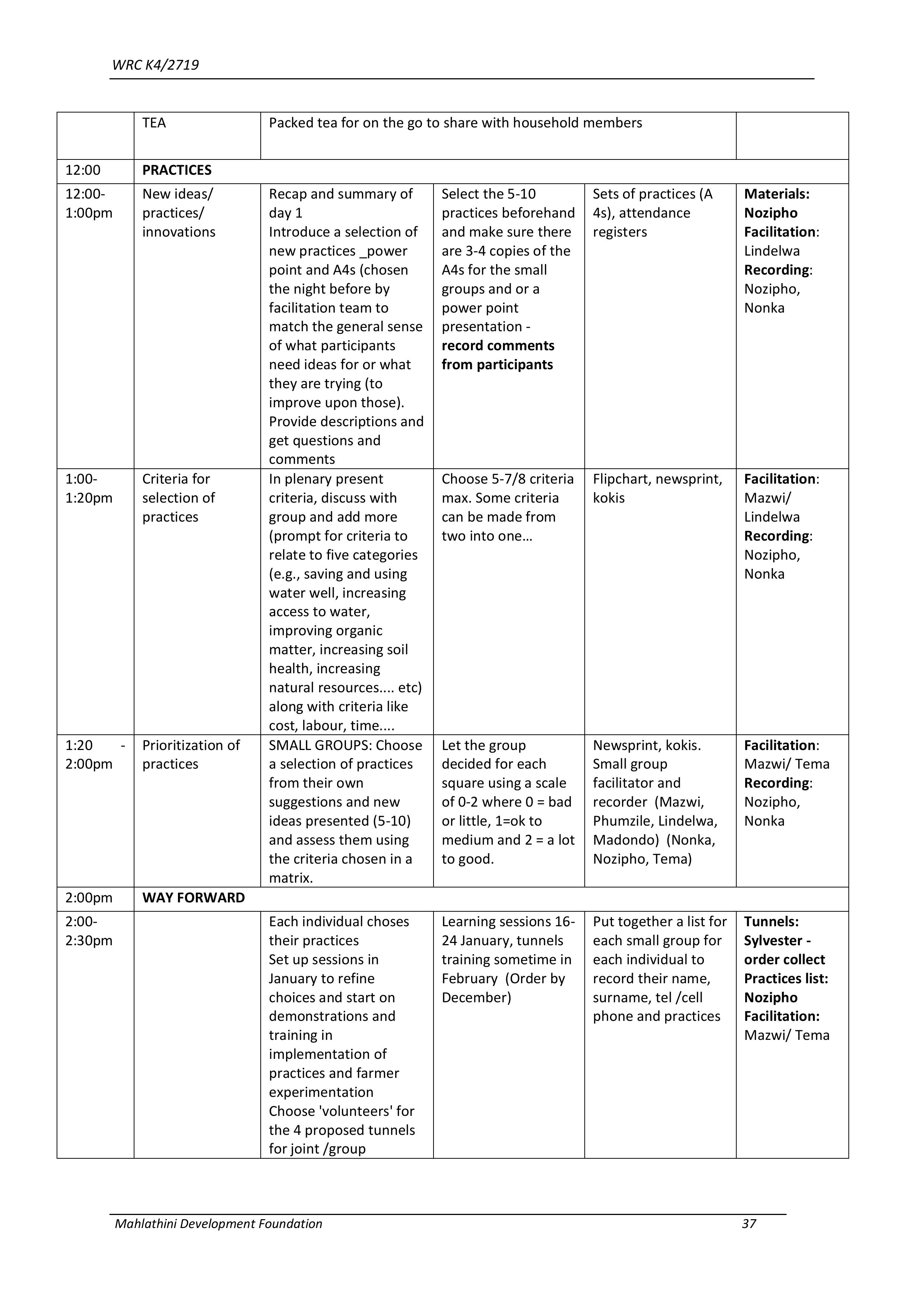

Design of the CCA community level workshop outline

By Erna Kruger

A number of smaller preparation session were undertaken prior to the joint process planning

workshop –designed to set out the community level methodology and process for introducing the

Climate Change concepts and the decision support process.

At the workshop a joint methodology was agreed upon and a process outline was developed.

The table belowindicates the outline for 2 workshops to be conducted in KZNand thus names the

team involved there. As a generic outline the team members will change, but the rest is meant to

remain similar throughout.

Community level climate change adaptation exploration workshop outline

DAY 1

Time

Activity

Process

Notes

Materials

Who

9:00am

INTRODUCTION

9:00-

9:45am

Community and

team

introductions

In pairs, take 5 minutes

to talk to each other.

Then introduce each

other to the group.

Choose a person you

don’t know well (both

team and community).

[include Name and

surname, farming

activities (garden, field,

livestock natural

Depending on the

size of the group,

this can take a long

time. If time is short,

then just do a quick

round of intro's.

Attendance register

- with columns for

farming enterprises

(so that each

participant can tick

what they do) - in

English and

Zulu/Pedi. Name

tags; stickers, kokis

Nozipho

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 34

resources), income from

farming]

Purpose of the

day

Introduction of the

organisation/s and

purpose of this

workshop- link to

already ongoing

activities if possible and

introduce visitors and

other stakeholders

involved

Talk to CC

necessitating

adaptation from us -

we may need to

change how we do

things and what we

do to - This w/s is to

help us explore

options for such

changes

Flipstand, newsprint,

kokis, data projector,

screen, extension

chords, plugs -

double adaptors.

Black refuse bags

and masking tape

(for blacking out

windows), camera-

and one person to

undertake to take

photos throughout

the day. Extra

batteries for camera

and sim card

Materials:

Nozipho,

Nonka

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

9:50am

PRESENT SITUATION

9:50-

10:30am

Present

livelihoods and

farming situation

- discuss impacts

related to CC

Use a series of impact

pictures- from the local

situation . Include the 5

categories (and describe

them to the group) -

water management

(increased efficiency

and access), soil

management (erosion

control ,fertility, health),

crops, livestock and

natural resources

Impact pictures-

either ppt or printed

on A4 to facilitate

dialogue (or both)

Record community

comments)

Power point

presentation

pictures

Mazwi - ppt

Facilitation:

Mazwi

Nozipho,

Nonka

10:30am

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

10:30-

11:30am

Discuss farming

activities as they

have changed ,

what they are

now and what

may happen in

the future if the

present trends

continue

SMALL GROUPS (5-

10people): facilitated

discussion on farming

activities (include the 5

categories) - prompt for

all five and keep

conversation focussed

OR

Facilitate a shorter

plenary discussion on

how things are changing

( if time is pressing)

Important to note

and record any

discussions around

changes and

adaptations- so

things people are

already doing to

accommodate for

changes - also where

they are not sure

what to do

Small groups; each

needs a facilitator

and recorder

(Mazwi, Phumzile,

Lindelwa, Madondo)

(Nonka, Nozipho,

Tema),

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

11:30am-

12:00pm

TEA

Fruit (apples, oranges, biscuits, juice and water, paper cups (lots) and

plates… Generous helpings - and lots of juice if it is hot. Find someone to

be in charge of food and refreshments, while the rest of the workshop

continues

Nozipo,

Nonka, Tema

12:00am

CLIMATE CHANGE PREDICTIONS

WRC K4/2719

Mahlathini Development Foundation 35

12:00 -

12:50pm

Summary of

predictions for

the locality (from

scientific

basis)[15min]

Present to group - using

flipchart or power point

- Keep it simple with

brief bold statements

that can be

remembered. Include

concepts of certainty -

and CC scenarios -

unmitigated, neutral

and mitigated

Facilitation:

Mazwi/Tema

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

Weather vs

Climate [10min]

Role play; phone

conversation - weekend

visit for weather,

relocating to an area for

seasonality/climate.

check in with

participants how

they understand the

difference from the

role play

Facilitation:

Mazwi, Nonka

Seasonality

diagrams

[25min]

SMALL GROUPS (5-

10people): facilitated

discussion on

temperatures for each

month of the year- in a

normal year and then

discuss how this is

chaning and going to

change. Start with the

hottest month and then

the coldest month as

reference points

Do temperature frist

or if the group is

small and works

quickly inlcude

rainfall then on the

same chart.

Easy to use kebab

sticks bought from

supermarket for this.

Small groups; each

needs a facilitator

and recorder

(Mazwi, Phumzile,

Lindelwa, Madondo)

(Nonka, Nozipho,

Tema),

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

1:00pm

REALITY/IMPACT MAPS

1:00-

2:00pm

Impact of CC

mind map

SMALL GROUPS (5-

10people): facilitated

discussion - MIND MAP

of livelihood and

farming impacts (using

the 5 categories) using

Hotter (drier) as the

starting point -

LINKAGES between

cards on the mind map -

make arrows (and

include more cards if

need be and discuss

(e.g. hotter soils, lead to

poor germination lead

to poor yields lead to

hunger)

Prompt for social,

economic,

environmental

impacts as well if

these don't come up

in the group…

Small groups; each

needs a facilitator

and recorder

(Mazwi, Phumzile,

Lindelwa, Madondo)

(Nonka, Nozipho,

Tema) CARDS-

Coloured paper of

differnet colours cut

into squares

Nozipho -

prepare cards

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

2:00-

2:30pm

Possible adaptive

measures

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS:

things that people

know, have changed,

have tried and or are

trying to deal with the

changes. Use different

coloured cards to attach

these solutions to the

mind map. If

participants are

struggling then rephrase

Also make a

separate list on

newsprint of names

of people trying

things plus the

innovation they are

trying (this is to

facilitate h/h visits

on day 2)

The cards need to be

written in local

language with

smaller translations

in English written in

on the cards as well

(to avoid the need

for alter translations)

Facilitation:

Lindelwa

Recording:

Nozipho,

Nonka

WRC K4/2719