MDFWRC-00746. Deliverable 1. August 2022

WaterResearchCommission

Submittedto:

ExecutiveManager:WaterUtilisationinAgriculture

WaterResearchCommission

Pretoria

Projectteam:

MahlathiniDevelopmentFoundaction(MDF)

ErnaKruger

Temakholo Mathebula

Betty Maimela

Ayanda Madlala

Nqe Dlamini

InstituteofNaturalResources(INR)

BrigidLetty

EnvironmentalandRuralSolutions (ERS)

NickieMcCleod,SissieMathela

Associationfor WaterandRuralDevelopment(AWARD)

DerickduToit

Project Number: C2022/2023-00746

Project Title: Dissemination and scaling of a decision support framework for CCA for smallholder

farmers in South Africa

Deliverable No.1:Desk top review of progress and present implementation of South African policy

and implementation frameworks and stakeholder platforms for CCA.

Date: 1 August 2022

Deliverable

1

2

CONTENTS

Contents ...................................................................................................................................................2

1.INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................3

2.South African policy, strategy development and implementation .................................................5

3.Integration of DSS in scaling (up and out).......................................................................................7

a.International decision support tools and platforms................................................................9

b.Adaptation platforms and decisions support Frameworks for South Africa...........................9

4.Further conceptual Development: Considerations .......................................................................10

a.Methodological approaches to adaptation...........................................................................10

b.Knowledge co-production .....................................................................................................13

c.Vulnerability assessments.....................................................................................................14

d.Adaptive Management ..........................................................................................................18

e.Local Food Systems ................................................................................................................19

f.Agroecology ...........................................................................................................................21

5.Multistakeholder platforms...........................................................................................................23

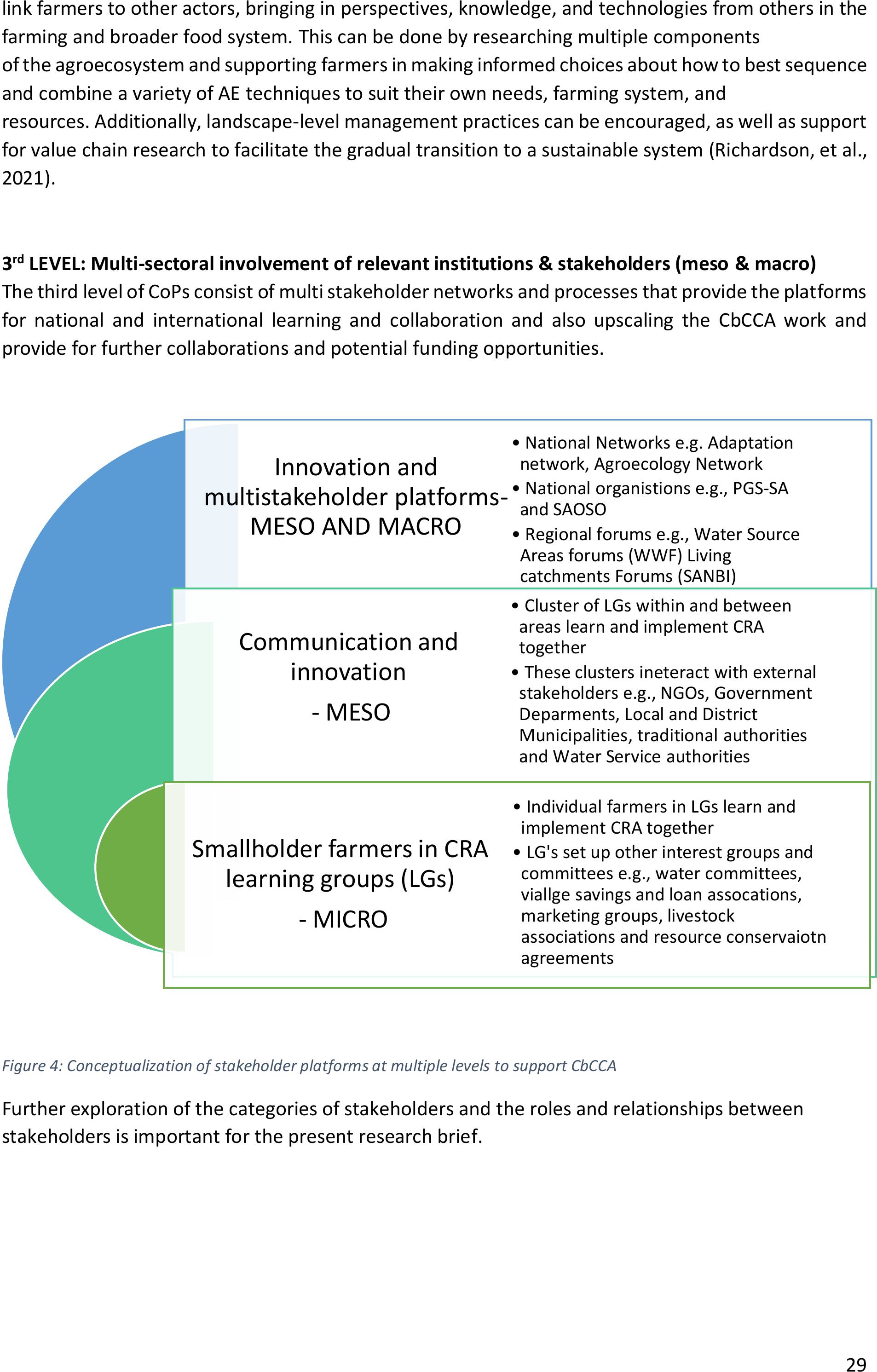

a.CbCCA conceptualization of stakeholder platforms..............................................................28

b.Process planning and progress to date..................................................................................30

c.Work plan: August-December 2022......................................................................................32

6.References .....................................................................................................................................33

Figure 1: Frames to understand adaptation effectiveness range across a continuum of being process-

or outcome-based. Source: (Singh, et al., 2021) ...................................................................................11

Figure 2: Critical processes to foster co-productive agility in each of the four pathways to

sustainability transformations...............................................................................................................14

Figure 3: The component of climate vulnerability and climate risk, adapted from IPCC AR5 ( (GIZ, with

EURAC and Adelphi, 2017).....................................................................................................................15

Figure 4: Conceptualization of stakeholder platforms at multiple levels to support CbCCA ................29

3

1.INTRODUCTION

This section provides a brief summary of the project vision, outcomes and operational details.

OUTCOME

Vertical and horizontal integration of this community- based climate change adaptation (CbCCA) model and

process lead to improved water and environmental resources management, improved rural livelihoods and

improved climate resilience for smallholder farmers in communal tenure areas of South Africa.

EXPECTED IMPACTS

1.Scaling out and scaling up of the CRA frameworks and implementation strategies lead to greater

resilience and food security for smallholder farmers in their locality.

2.Incorporation of the smallholder decision support framework and CRA implementation into a range of

programmatic and institutional processes

3.Improved awareness and implementation of appropriate agricultural and water management practices

and CbCCA in a range of bioclimatic and institutional settings

4.Contribution of a robust CC resilience impact measurement tool for local, regional and national

monitoring processes.

5.Concrete examples and models for ownership and management of local group-based water access and

infrastructure.

AIMS

No

Aim

1.

Create and strengthen integrated institutional frameworks and mechanisms for

scaling up proven multi-benefit approaches that promote collective action and

coherent policies.

2.

Scaling up integrated approaches and practices in CbCCA.

3.

Monitoring and assessment of environmental benefits and agro-ecosystem

resilience.

4.

Improvement of water resource management and governance, including

community ownership and bottom-up approaches.

5.Chronology of activities

1.Desktop review of CbCCA policy and implementation presently undertaken in South Africa

2.Set up CoPs:

a.Village based learning groups: A minimum of 1-3 LGs per province will be brought on board.

b.Innovation platforms: 3 LG clusters, one for each province consisting of a minimum of 9- 36

LGs will be identified to engage coherently in this research and dissemination process.

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Engage existing multistakeholder platforms such as UCPP, LCP,

AN etc

3.Develop roles and implementation parameters for each CoP

a.Village based learning groups: CCA learning and review cycles, farmer level experimentation,

CRA practices refinement, local food systems development, water and resource

conservation access and management and participation and sharing in and across villages.

4

b.Innovation Platforms (IP): Clusters of LGs learn and share together with local and regional

stakeholders for knowledge mediation and co-creation and engagement of Government

Departments and officials (1-2 sessions annually for each IP)

c.Multistakeholder platforms: Development of CbCCA frameworks, implementation

processes (including for example linkages to IDPS and disaster risk reduction planning and

implementation at DM and LM level), reporting frameworks for the NDC to the CCA

strategy, consideration of models for measurement of resilience and impact (1- 2 sessions

annually for each multi stakeholder platform)

4.Cyclical implementation for all three CoP levels (information provision and sharing, analysis, action,

and review) within the following thematic focus areas: Climate resilient agriculture practices,

smallholder microfinance options, local food systems and marketing and community owned water

and resources access and conservation management plans and processes. Each of these thematic

areas is to be led by one of the senior researchers and a small sub-team.

5.Monitoring and evaluation: Consisting of the following broad actions:

a.Focus on 3-4 main quantitative indicators e.g. water productivity, production yields, soil

organic carbon and soil health

b.Indicator development for resilience and impact and

c.Exploration of further useful models to develop and overarching framework.

6.Production of synthesis reports, handbooks and process manuals emanating from steps 1-4 with the

primary aim of dissemination of information.

7.And refinement of the CbCCA decision support platform, incorporating updated data sets and

further information form this research and dissemination process.

DELIVERABLES

No.

Deliverable Title

Description

Target Date

Amount

1

Desk top review for CbCCA

in South Africa

Desk top review of South African policy,

implementation frameworks and

stakeholder platforms for CCA.

01/Aug/2022

R100 000,00

2

Report: Monitoring

framework, ratified by

multiple stakeholders

Exploration of appropriate monitoring

tools to suite the contextual needs for

evidence-based planning and

implementation.

02/Dec/2022

R100 000,00

3

Handbook on scenarios and

options for successful

smallholder financial

services within the South

Africa

Summarize VSLA interventions in SA,

Govt and Non-Govt and design best bet

implementation process for smallholder

microfinance options.

28/Feb/2022

R100 000,00

4

Development of CoPs and

multi stakeholder

platforms

Design development parameters, roles

and implementation frameworks for

CoPs at all levels, CRA learning groups,

Innovation and multi stakeholder

platforms; within the CbCCA

framework.

04/Aug/2023

R133 000,00

5

Report: Local food systems

and marketing strategies

Guidelines and case studies for building

resilience in local food systems and

08/Dec/2023

R133 000,00

5

contextualized - Guidelines

for implementation

local marketing strategies towards

sustainable local food systems (local

value chain)

6

Case studies: encouraging

community ownership of

water and natural

resources access and

management

Case studies (x3) towards providing an

evidence base for encouraging

community ownership of natural

resource management through bottom-

up approaches and institutional

recognition of these processes.

28/Feb/2024

R134 000,00

7

Case studies: CbCCA

implementation case

studies in 3 different

agroecological zones in SA

CbCCA implementation case studies in 3

different agroecological zones within

South Africa

12/Aug/2024

R133 000,00

8

Refined CbCCA decision

support framework with

updated databases and

CRA practices

Refined CbCCA DSS database and

methodology with inclusion of further

viable and appropriate CRA practices

13/Dec/2024

R133 000,00

9

Manual for implementation

of successful

multistakeholder platforms

in CbCCA

Methodology and process manual for

successful multi stakeholder platform

development in CbCCA

28/Feb/2025

R134 000,00

10

Final Report

Final report: Summary of all findings,

guidelines and case studies, learning

and recommendations

18/Aug/2025

(Feb 2026)

R400 000,00

Deliverable 1, being a desk top review of progress and present implementation of South African policy

and implementation frameworks and stakeholder platforms for CCA is meant to be an update on the

desk top review conducted for this process in 2017 and aims to review all relevant documentation

about the latest strategy and policy implementation frameworks forCCA both within Government and

multistakeholder forums and toprovide a SWOT analysis to develop a coherent methodology for

multistakeholder engagement.

Given the present fragmented state of multistakeholder platforms a SWOT analysis has not been seen

to be appropriate. Further analysis will be undertaken in the next deliverable.

2.SOUTH AFRICAN POLICY, STRATEGY DEVELOPMENTANDIMPLEMENTATION

Written by Betty Maimela

According to the LTAS (Long Term Adaptation Scenarios) factsheet on Agriculture “adapting

agricultural and forestry practices in South Africa requires anintegrated approach that addresses

multiple stressors and combines indigenous knowledge and experience with the latest scientific

insights. For large-scale commercial farmers, adaptation needs to focus on maximising output in a

sustainable manner and maintaining a competitive edge in changingclimatic conditions. For rural

livelihoods, adaptation needs to focus on vulnerable groups and areas and include promoting climate-

resilient agricultural practices and livelihoods. Promoting alternative, sustainable sources of income

will be important for subsistence households that are unable to continue farming.

6

As an overall adaptation strategy, benefits would come from practices based on best management

andclimate-resilient principles, characteristic of concepts such as climate smart agriculture,

conservation agriculture, ecosystem- and community-based adaptation, andagroecology. Such

practices include restoring and rehabilitating ecosystems tooptimise them for future climatic

conditions, minimising soil disturbance, maintaining soil cover, maximisingwater storage, multi-

croppingand integrating cropand livestock production to optimise yields, sequestering carbon, and

minimising methane and nitrous oxide emissions” (DEA, 2019)

Diversification in the agriculture sector is seen to include in-

field and off-field water harvesting and storage to assist with

increased irrigation requirements (without compromising

water availability), finding new, climatically suitable

locations for crops and commercial forests, growing

indigenous species and farming indigenous and locally

adapted breedswhich are heat and drought tolerant,

harvesting less often to prevent nutrient depletion, using

local techniques to decrease wind erosion (such as mulch

strips for shelter belts of natural vegetation), and planting

climate-resilient crop varieties, such as drought-resistant

maize varieties, alternative crops or late-maturing fruit trees.

Climate advisory services could usefully communicate key

messages from the latest available science in an appropriate

format to government, agri-business, extension services and

farmers. Communication and trust should be increased

between authorities and all farmingsectors (commercial, small-holder and subsistence) to

disseminate relevant knowledge on climate change and promote adaptation (DEA, 2019).

Adaptation strategies are to be integrated into sectoral plans, including: The National Water Resource

Strategy, as well as reconciliation strategies for particular catchments and water supply systems; The

Strategic Plan for South African Agriculture; TheNational Biodiversity Strategy andAction Plan, as well

as provincial biodiversity sector plans and local bioregional plans; The Department of Health Strategic

Plan; The Comprehensive Plan for the Development ofSustainable Human Settlements; and the

National Framework for Disaster Risk Management (DEA, November 2021).

The recently submitted Climate Change Bill, lendslegal muscle to this process(Draft Climate change

Bill, 2021. www.dffe.gov.za). The draft law aims to establish a Ministerial Committee on Climate

Change tooversee and coordinate the activities across all sector departments. Under the proposed

legislation, the Minister responsible for Environmental Affairs together with the Ministerial

Committee on Climate Change would have to set sectoral emission targets (SETs)for each GHG

emitting sector in line with the national emission target, every five years and carbon budgets would

be allocated to significant GHG emitting companies. Carbon budgets would put a capon emissions

and make it mandatory for companies to constrain their emissions.

In addition, the bill places a legal obligation on every organ of state to coordinate and harmonise their

various policies, plans, programmes, decisions and decision-making processes relating to climate

change. Local officials – including mayors–will be required to undertake a climate change needs and

response assessment within one year of the publication of the National Adaptation Strategy and Plan.

The bill furtherrequires a climate change response implementation plan to be developed within two

years of undertaking the climate change needs and response assessment. However, the disconnect

Adaptation refers to adjustments in

ecological, social, or economic systems in

response to actual or expected climatic stimuli

and their effects or impacts. Itrefers to

changes in processes,practices, and

structures to moderate potential damages or

to benefit from opportunities associated with

climate change. (UNFCCC 2014) (DEA,

November 2021).

Climate resilienceis thecapacity of social or

ecological systems to recover orbounce back

from disturbances, shocks and extreme loads

or to absorb these disturbances while

retaining the same basic structure and ways of

functioning (UNDP 2005; UN/ISDR2004; IPCC

2007; Rockefeller Foundation 2009; Arctic

Council 2013 referred to in IPCC 2014).

7

between the higher echelons of government and the more localised organisations (both public and

private) who are meant to do the implementation, persists even here.

The DALRRD has been allocated as the lead department for climate adaptation action in South Africa.

The internal orientation and vision of this department however focuses on generation of “equitable

access and participation in a globally competitive, profitable and sustainable agricultural sector

contributing to a better life for all”, with a very strong focus on profitability, investments, equity and

governance. CCA is not a central theme (DALRRD, 2013).

The basic approach of the agriculture CC adaptation and mitigation sector plan is “climate smart

agriculture, which entails theintegration of land suitability, land use planning, agriculture and forestry

to ensure that synergies are properly captured and that these synergies will enhance resilience,

adaptive capacity and mitigation potential” (DAFF, 2015). The assumption is that if the smallholder

farming sector can deal with issues ofpoor commercialisation, poor infrastructure and low farm

productivity, with “strong extension services and good communication and trust between local

government and the entire farming community (commercial and emerging) to bring about concrete

changes, … this would facilitate preparedness for climate change” (DAFF, 2015).

As such the main response of the Department for CCA is seen to be their LandCare programme which

“is a community based and government supported approach to the sustainable management and use

of agricultural natural resources. The overall goal of LandCare is to optimise productivity and

sustainability of natural resources so as toresultin greater productivity, food security, job creation and

better quality of life for all”. In budgetary terms the entire function of natural resource management

and disaster management is provided with around 17% of the total annual budgetof around R16,8

billion for 2022, which means an annual budget for LandCare which is at best around R360 million for

the whole of South Africa, around 4% of the total budget.For this year, the budget is to beused within

the Department only and no callsfor proposals from communities have been put forward (Pers comm.

Mrs T Naidoo -KZN LandCare Unit, July 2022).Any implementation can thus be regarded as minimal

and indicates a severe disconnect between policy, strategy, and implementation for our public service

bodies.

3.INTEGRATION OFDSS IN SCALING (UP AND OUT)

A quote from a paper written in 2014 is as relevant today as 8 years ago. “Adaptation responses are

emerging in certain sectors. Some notable city-scale and project-based adaptation responses have

been implemented, but institutional challenges persist. In addition,a number of knowledge gaps

remain in relation to the biophysical and socio-economic impacts of climate change. A particular need

is to develop South Africa's capacity to undertake integrated assessments of climate change that can

support climate-resilient development planning.”(Ziervogel, et al., 2014).

Efforts have been focused on the policy and legal processes of the NCASS and the Climate Bill and

sectoral integration under Government Departments, with DALRRD (Department of Agriculture, Land

Reformand Rural Development)being the leadand including biodiversity and ecosystems, health,

energy, transportation, human settlements and disaster risk management. The intention of these

documents and the white paper is to enable adaptation planning across and between all Government

sectors and Departments and mainstreaming of climate action into theintegrated development

planning process (DEA, 2017). In addition, a focus on vulnerability assessments as well as information

and data provision related to different sectors, as per the Let’s Respond Toolkit(Sustainable Energy

8

Africa and Palmer Devlopment Group., April 2012)and the more recent GreenBook- an online toolkit,

(CSIR, 2019), at Local Municipal level, would provide the specific context for integration of climate

actions into the development planning. In practice, very little progresshasbeen made and a policy-

practice decoupling has been noted through various case studies where resources are prioritized to

service delivery issues that politicians deem as more important than responding to climatechange

(Mankolo, 2016), (Chademana, 2019), (Santhia, Shackleton, & Pereira, 2018), (Pieterse, du Toit, &van

Niekerk, 2021).

A review of success factors for CbCCA through the Community Adaptation Small Grants Facility

provides weight to this argument (CA-SGF, 2018). Their learnings were summarized as follows:

1.A holistic approach is required to address the complexitiesof the challenges

experienced by local communities and designing interventions that address, or at least

acknowledge, the multitude of factorsthat contribute to climate resilience. Integrated

interventions can be used to leverage multiple benefits effectively

2.Partnerships with external stakeholders at multiplelevels and in various forms were

critical for success allowing for skills transfer, leveraging of expertise, and flexibility to

access resources as needed

3.Participatory, inclusive and locally drivenprocesses arerequired for climate

adaptation intervention success.Locally determined interventions, based upon

community priorities and supported by local leadership, can bolster achievements

4.Projects must plan for sustainabilityfrom the outset and account for a range of

climate change impacts based upon scientific projections, including the sustainability

and maintenance of assets developed during a project

5.Adopting adaptive management practices promotes the responsiveness and

customization requiredfor Community-Based Climate Change Adaptation projects.

6.Capacity building is an integral componenttocommunity-based interventions, as

new technical information becomes available. The breadth and level of capacity

building span various technical expertise and includes financial and administrative

skills as well as project management.

This means that approaches and processes for integration of climate action planning and

implementation at municipal and provincial level still need to be found, despite the comprehensive

national policy and reporting processes. One way to undertake such assessments, linked to climate

resilient development planning is the use of the CbCCA adaptation platform designed under the WRC

brief (K5/2719/4): Collaborative knowledge creation and mediation strategies for the dissemination of

water and soil conservation practices and Climate Smart Agriculture in smallholder farming systems

(2017-2020). This model provides a reasonably comprehensive process for climate vulnerability

assessment including socio-economic, biophysical, climate and weather and agricultural data to

provide options and practices forimplementation of climate change adaptation (CCA) strategies which

are context based and can be used in local and regional planning processes.

It can provide a local, practical engagement process with Municipal Governance Structures and other

stakeholders tointegrate climate action intotheir agendas. A quick trawl of recent literature for South

Africa indicates that this is still the only bespoke process of its kind in South Africa.

9

a.International decision support tools and platforms

Effective adaptation to climate change requires support for sound decision making and good practice.

Over the past two decades, a proliferation of decision-making

resources and tools has emerged (Street, Pringle, Lourenço,

& Mariana, 2019). Mostly, these are online tools andrange

fromsimple climate data delivery platforms to complex risk

management frameworks providing data, guidance, tools and

other documents to support adaptation. They are usually

targeted geographically andby sector and are designed for a

particular clientele.

There are some challenges in designing and disseminating

effective decision support tools, some to do with the tools

themselves in that they need to be accessible useable, useful

and reliable and needto remain relevant in a fast-changing

environment, which all mean that the developers need to

have a good understanding of their audience. Other

challenges may include unrealisticexpectations from users,

lack of sustained funding forreviewing, updating and addition

of new content and a changing policy context that may

require more targeted support for modest interventions

rather than comprehensive system wide plans (Street &

Palutikof, 2020).

This need for flexibility requires a design andimplementation

process based on continuous learning and improvement,

consisting oftailoring the platforms to match the capabilities

and needs of the intended users, sustained monitoring and

evaluation, developing partnerships that enhance the

ownership by users and user communities and understanding

the factors that motivate use of the tools and enable or act as

barriers to implementation of the resulting plans (Palutikof, Street and Gardiner 2019);

Latest trends have shown an interest in:

-Developing and implementing effective strategies for coproduction of decision support

resources, involving practitioners at all stages of the process.

-Linking climate change adaptation, disaster riskreduction and the sustainable development

goals.

-Embedding technical innovations to increase functionality and user friendliness, including

more attention to navigability, accessibility, legitimacy and relevance.

-Providing examples of good practice related to supporting evolving user requirements and

-Supporting a broader range ofusers (Street & Palutikof, 2020).

b.Adaptation platforms and decisions support frameworks for South Africa

Most decision support processes for planning climate action are online processes designed to provide

information and planning support at the level of policy, strategy and high- level government

interventions, both internationally and nationally. For South Africa the LTAS (Long Terms Adaptation

Scenarios) is a good example of high-level provision of information for decision making and planning.

The first report was published in 2013 (DEA, 2013). Six individual technical reports have been

Adaptation Platforms: Enabling

environments, equipping decision-makers

with the data, tools, guidance, and

information needed to adapt to a changing

climate. Content is usually, but not always,

delivered online and may include facilitation

of knowledge and capacity building through

networking, learning opportunities, and case

studies on adaptation planning and

implementation. They are intended to

provide the user with everything required to

undertake adaptation, from scoping the

challenge through to monitoring and

evaluating adaptation outcomes.

Decision-Support Frameworks (also known

as a decision support systems): A risk

management framework for climate change

adaptation together with the decision

support tools necessary to implement the

framework. The tools may include case

studies demonstrating the application of the

framework.

Decision Support Tools: Methods and other

knowledge resources that facilitate decision-

making for adaptation to climate change.

They may be free-standing, or components

of Adaptation Platforms.

Climate Services: Covers the transformation

of climate-related data – together with

other relevant information – into

customised products

(Street &Palutikof, 2020)

10

developed to summarize the findings from Phase 1, including onetechnical report on climate trends

and scenarios for South Africa and five summarizing the climate change implications for primary

sectors: water, agriculture and forestry, human health, marine fisheries, and biodiversity.

This work was followed-up by the two online climate action planning support online toolkits; the Let’s

Respond toolkit and the South African Green Book.

The Let’s Respond Toolkit (DEA and GIZ) has beendeveloped tointegrate climate change risks and

opportunitiesinto municipal planning, building on the initial LTASresearch process and providing an

online resource of information as well as tools to respond to climate change at a local level as part of

the Local Government Climate Change Support Programme (DEA, 2017). It includes a vulnerability

assessment toolkit, climate change response plan templates and a stakeholder engagement toolkit.

The South African Green Book is an online planning support tool that providesquantitative scientific

evidence on the likely impacts that climatechange and urbanisation will have on South Africa’s cities

and towns, as well as presenting a number of adaptation actions that can be implemented by local

government to support climate resilient development. The Green Book was co-funded by the CSIR and

the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), between 2016 and 2019. The CSIR has

partnered with the National Disaster Management Centre (NDMC) and co-developed this product

with universities, government departments, NGOs and other peer groups.

It provides evidence of current and future (2050) climate risks and vulnerability for every local

municipality in South Africa (including settlements) in the form of climate-change projections,

multidimensional vulnerability indicators,population-growth projections, and climate hazard and

impact modelling. Based on this evidence, the Green Book developed a menu of planning-related

adaptation actions and offers support inthe selection of appropriate actionsfrom this menuto be

integrated into local development strategies and plans.

4.FURTHER CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT:CONSIDERATIONS

Reframing anddevelopment of new frameworks, methodologies andperspectives is an ongoing

process in development and CCthinking. Below short summaries are provided of progress in aspects

relevant to the overall CbCCA models.

a.Methodological approaches to adaptation

There are still conceptual and methodological challenges in defining adaptation goals and in what

effective adaptation looks like, with anumber of seemingly divergent approaches being used.

Assessments, implementation and impact measurements are not thesame across these approaches,

notwithstanding calls forstandardization on nationallevels towards coherent reporting of the NDC

(Nationally Determined Contributions). Since the Paris Agreement nations are required to consider

their contributions towards theglobal goalonadaptation as well as adequacy and effectiveness of

their adaptation responses. A recent comprehensive review of these concepts within a very wide

range of literature by a group of international experts, has outlined eleven guiding principles for

adaptation research and practice (Singh, et al., 2021).

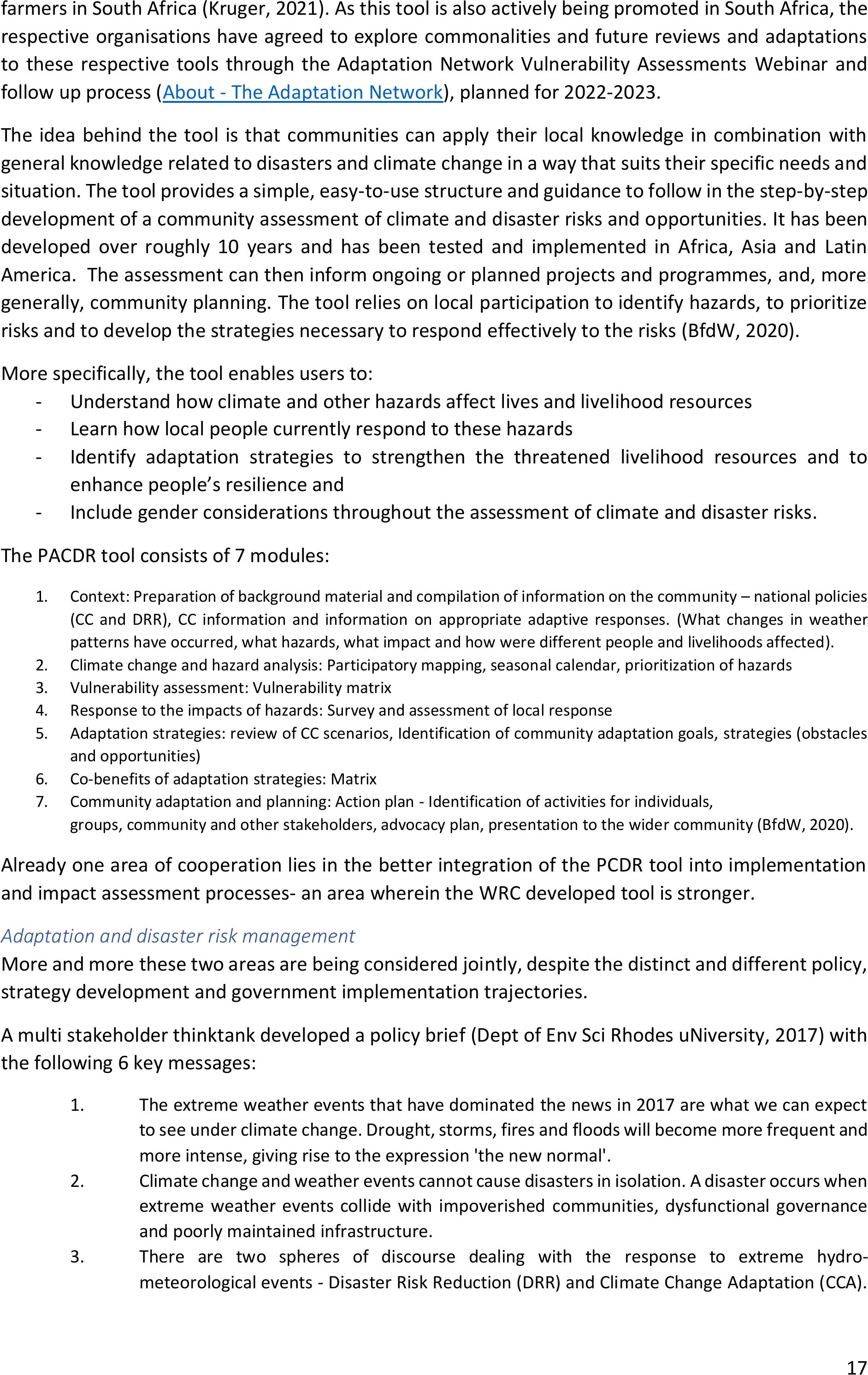

The frames underlying the principles, outline thedifferent views in understanding and

operationalizing adaptation effectivenessand “suggest that opening up thinking about the purpose,

processes, and outcomes of adaptation from different perspectives can lead to(1) better

11

conceptualized and designed adaptation processes, which acknowledge the inherent biases and

strengthsof different effectiveness approaches, and (2) adaptation outcomes that are better aligned

to the overarching SDG objective of ‘leaving no one behind’” (Singh, et al., 2021).

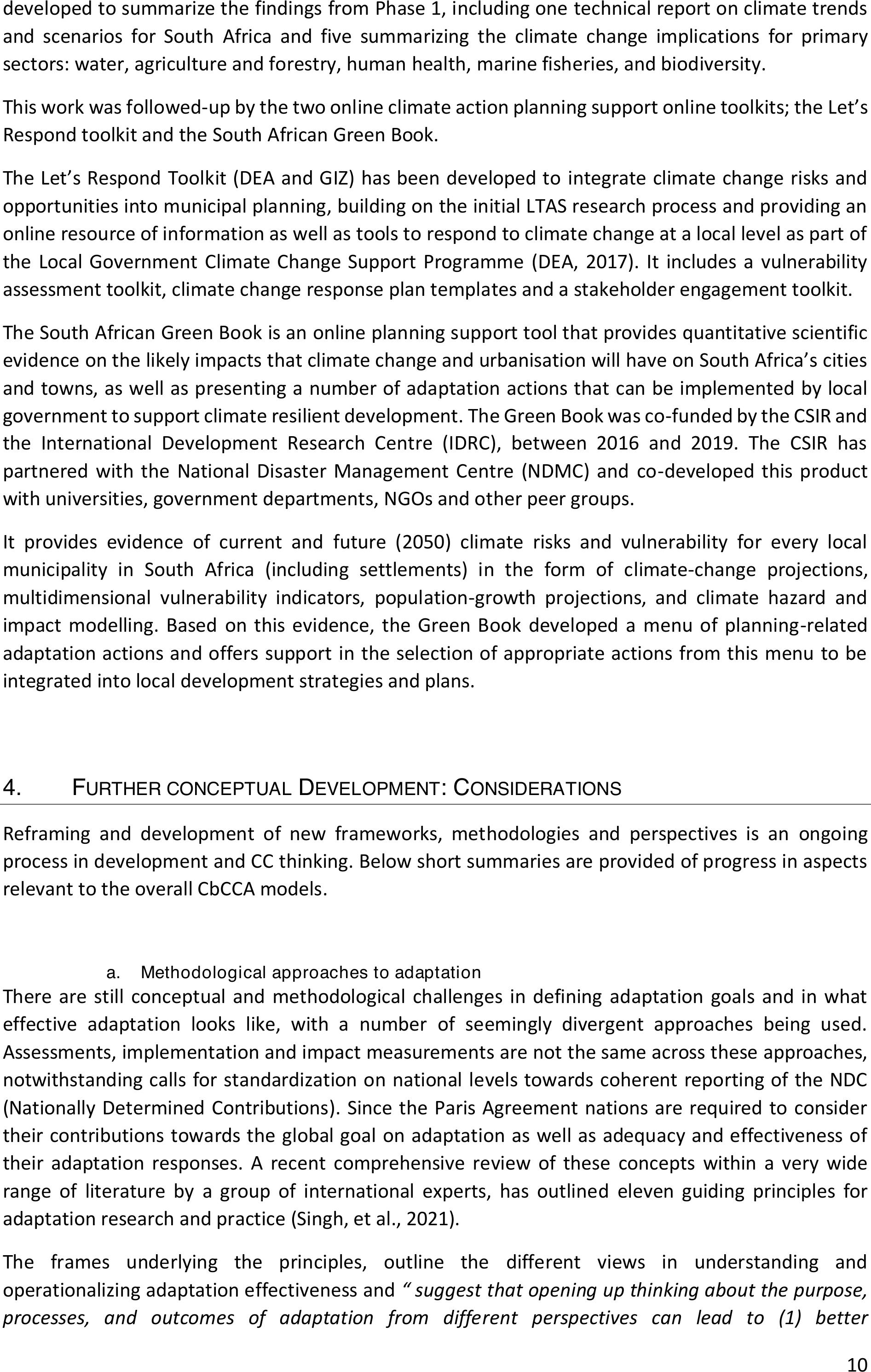

These framesare: (1) maximizing economic benefits;(2) improved wellbeing; (3) vulnerability

reduction or adaptive capacity enhancement; (4) enhanced resilience; (5)sustainable adaptation; (6)

avoiding maladaptation; (7) ecosystem-based adaptation; (8) community-based adaptation; (9)

adaptive governance; (10) ensuring equity and justice and (11) transformation.

Figure 1:Frames to understand adaptation effectiveness range across acontinuum of being process- or outcome-based.

Source: (Singh, et al., 2021)

The authorsthen linked these frames to a statement of principle that summarizes and defines the

approach:

1)Minimize costs and maximize benefits(Efficiency/Utilitarian): which looks at adaptation

interventions from financial and social cost perspectives and assumes that benefits can be

estimated and calculated.

2)Support achievement of material,subjective,and relational wellbeing goals(Improved well-

being): which broadly covers material, relational and subjective well-being, emphasizing the

agency of actors in determining their well-being, tending to focus on the individual

3)Reduce vulnerability and/orincrease adaptive capacity, especially of themost vulnerable and

those most at riskto climate change(Reduced vulnerability): which focuses on enhancing

capacities to adapt to, avoid, reduce, or capitalize on risk. Indicator-based vulnerability

assessment methods or participatory approaches, serve as metrics to monitor vulnerability

reduction over time. Projects of this nature dominate the adaptation landscape at present.

4)Increase resilience by building functional persistence over long timescales so that systems have

the ability to bounce back from climaticshocks(Enhanced resilience): which originates in the

Ecological Sciences and outlines three fundamental constituents of resilience within socio-

ecological systems theory as functional persistence, self-organization, and adaptation. Depending

on the scale andscope of the system being considered, the resilience framing helps focus on

temporal and spatial trade-offs and trade-offs between objectives (e.g.human well-being vs.

environmental services).

5)Be economically, ecologically, and socially sustainable, explicitly looking atlonger-term, cross-

generational viability of adaptation actions(Sustainable adaptation): which focuses on climate

change vulnerability and gaps in adaptive capacity and adheres to the principles of sustainable

development, moving towards goals of social equity and environmental integrity, looking

primarily at the confluence of vulnerability and poverty reduction.

12

6)Take into account unintended negative consequences and explicitly look atthe cross-scalar,

long-term impacts of adaptation actions(Avoiding maladaptation): which defines maladaptation

as action taken ostensibly to avoid or reduce vulnerability to climate changethat impacts

adversely on, or increases the vulnerability of other systems, sectors or social groups. It calls for

thinking of the most vulnerable, but lack of assessment metrics is a big gap in this approach.

7)Invest in ecosystem conservation, management and restoration toenhance ecosystem services,

and hence reduce impacts of climate change on humansystems(Ecosystem based adaptation):

Which highlights that human wellbeing and adaptive capacities are deeply dependent on

biodiversity and functioning ecosystem services and focuses on sustainable used of natural

resources and ecosystem functioning. Metrics includequantification of ecological limits and

indicator-based assessments of how adaptation strategies are benefiting/eroding ecosystem

services.

8)Be co-produced with communities toensure inclusive and sustainableadaptation(Community

based adaptation): Which is a bottom-up approach that focuses on increasing the participation

and agency of vulnerable communities in adaptation prioritization and implementation. It argues

that co-producing adaptation solutions can facilitate more effective adaptation.CbA explicitly

focusses on mainstreaming community priorities, needs, knowledge, and capacities into

adaptation thereby aiming to empower people to adapt more effectively. Participatory

vulnerability assessment tools before and after adaptation interventions are often used for

evidence-based adaptation planning and tracking adaptation outcomes.

9)Be oriented towards achieving transparency, accountability andrepresentation in governance

through multi-scalar, participatory, and inclusive processes(Adaptive governance): Whichdraws

fromresearch on managing complex, dynamic social-ecological systems to argue for institutions

that are flexible and forward-looking, have the capacity to prepare for uncertainty, and explicitly

address current climate change impacts, while planning for future risks. It includes also the

concept of good governance. A key assumption of this framing is that unequal powerstructures

can be balanced by greater participation and inclusion. While policy learning is seen to be

important in the multi-level governance literature, social learning is identified as critical in the

adaptation literature.

10)Be oriented toward socially just and equitable processes and outcomes(Equity/justice): Which

is a normative, people-centered approach that explicitly focusses on winners and losers from both

climate change impacts and adaptation action. It frames effective adaptation as redressing

imbalances to achieve more equitable adaptation and reduce socially unjust outcomes. It makes

the case for ensuring that the most vulnerable areshielded from climate impacts and thattheir

well-being is not compromised further through actions taken to respond to climate change. It

includes the concepts of gender equity and empowerment. Lack of good metrics is agap in this

approach.

11)Be a process that fundamentally changes human thinking and practices inthe face of climate

change and overtly challenge the powerstructures thatgenerate vulnerability to its impacts

(Transformation): Which generally assumes that climate change brings risks that are beyond

society’s ability to manage through ‘business-as-usual’ (or incremental)approaches to adaptation,

and that fundamental change is both feasible and desirable.Itis centrally concerned with reducing

marginalization and strengthening capacities of the most vulnerable

The frames and principles fall along a continuum and can simultaneously be process- and outcome-

based. The authorsargue that in practice, recognizing the strengths and blind spots of each frame

could mean funders and implementing agencies use combinationsof frames when tracking adaptation

progress (Singh, et al., 2021).

13

The adaptation platform developed in MDF’s pervious WRC brief includes element ofthe community-

based adaptation, reduced vulnerability, enhanced resilience and sustainable adaptation frames.

Issues related to adaptive governance as relates to water and natural resources aswell as

transformation through a focus on local food systems are to be considered within the present research

work package.

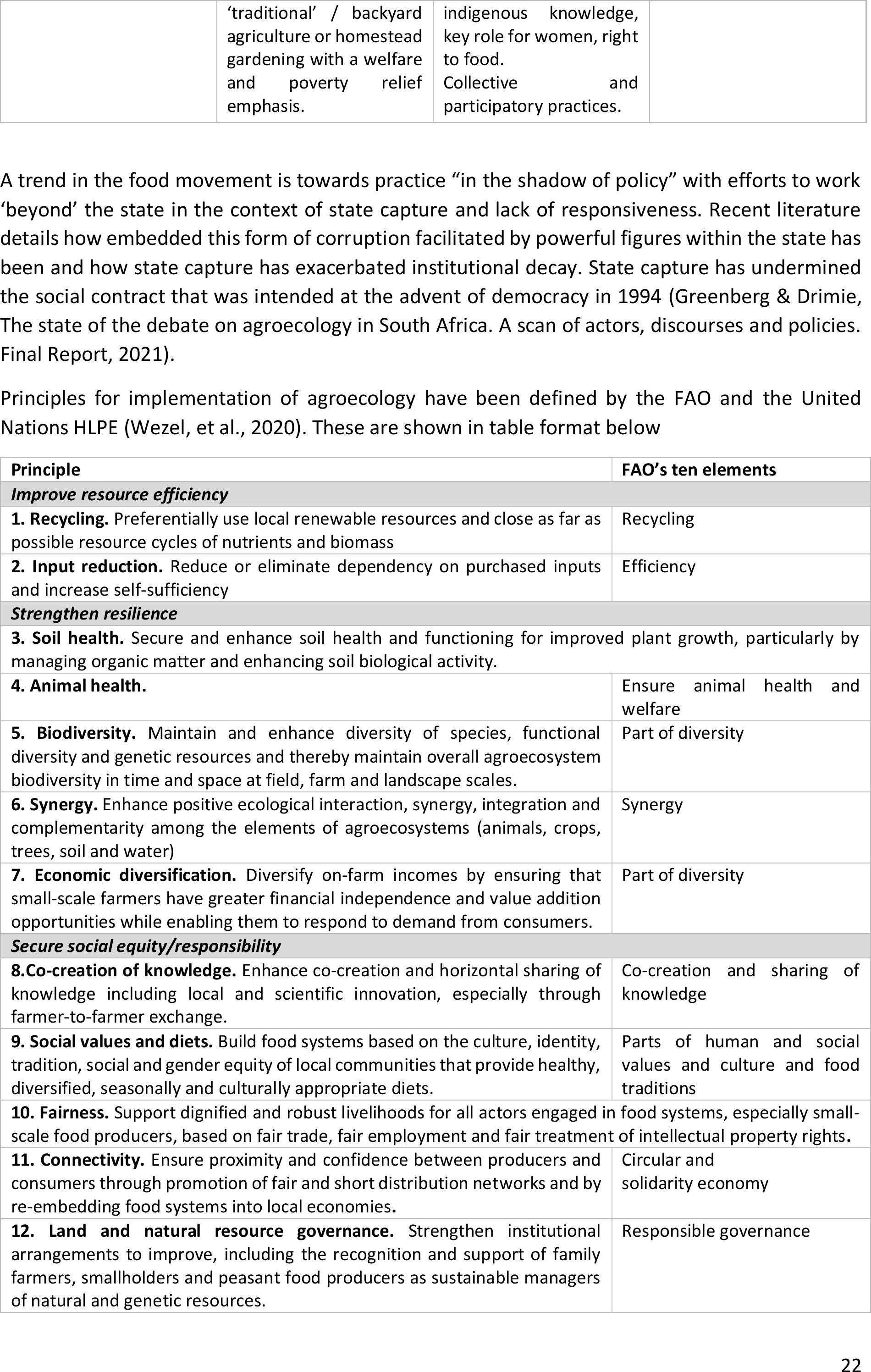

b.Knowledge co-production

Knowledge co-production or co-creation is a further important tenet of this research and the

smallholder farmer adaptation platform produced for community-based adaptation. A group of

international researchers analyzed32 initiatives worldwide that co-produced knowledge and action

to foster sustainable social-ecological relations (Chambers, et al., 2022).

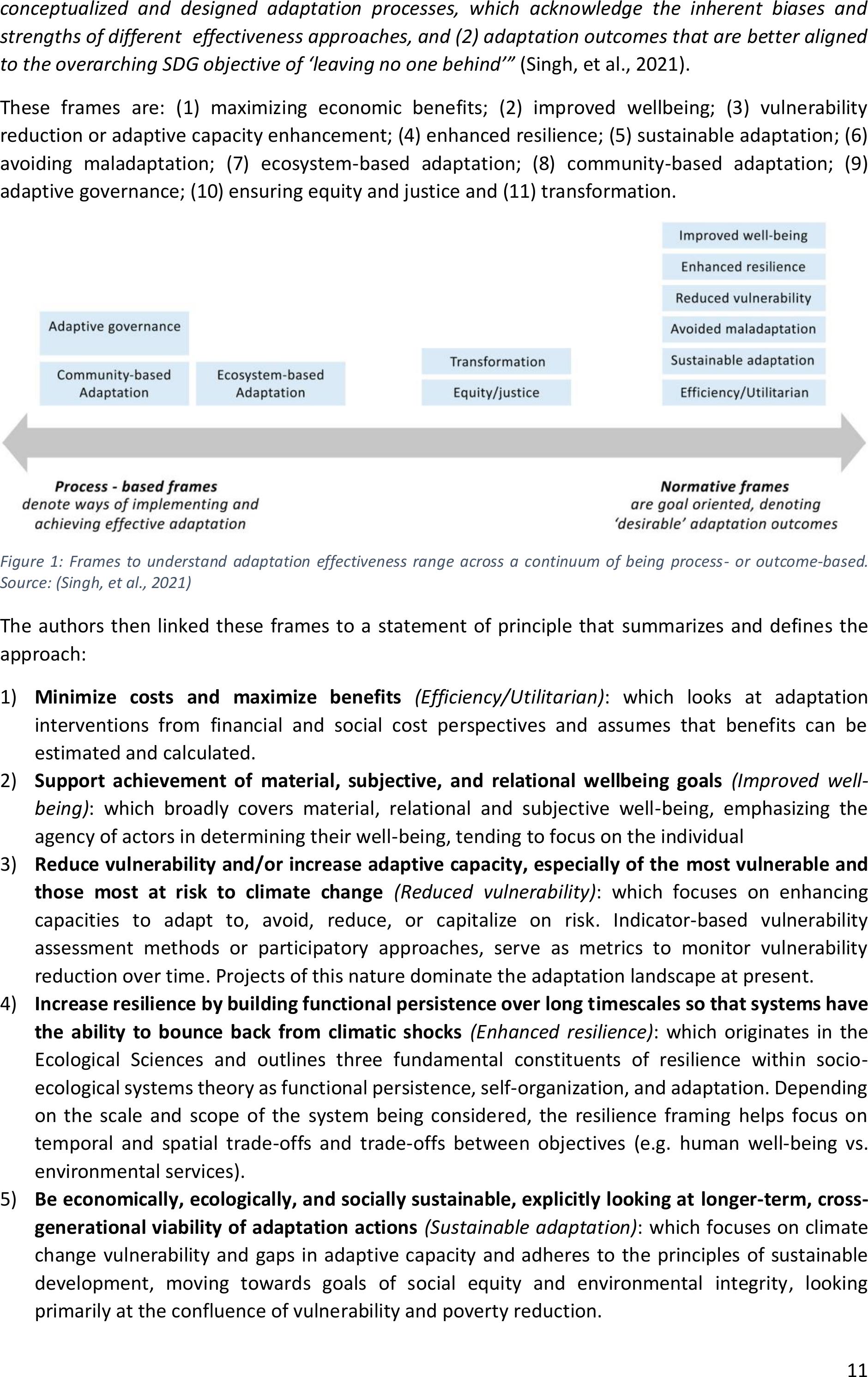

Co-production, the collaborative combining of research and practice by diverse role players, is argued

to beimportant in sustainability transformations. Yet, there is still poor understanding of how to

navigate the tensions that emerge in these processes. These authors argue for four distinct pathways

towardscollaborative co-creation leading to what they refer to as co-productive agility.According to

these authors “co-productive agility refers to the willingness and ability of diverse actors to iteratively

engage inreflexive dialogues to grow shared ideas and actions that would not have been possible from

the outset. It relies on embeddingknowledge production within processes of change to constantly

recognize, reposition, and navigate tensions and opportunities” (Chambers, et al., 2022).

“It relies on embedding knowledge production within processes of change to constantly recognize,

reposition, and navigate tensions and opportunities. Co-productive agility opens up multiple pathways

to transformation through: (1) elevating marginalized agendas in ways that maintain their integrity

and broaden struggles for justice; (2) questioning dominant agendas by engaging with power in ways

that challenge assumptions, (3) navigating conflicting agendas to actively transforminterlinked

paradigms, practices, and structuresand (4)exploring diverse agendas to foster learning and mutual

respect for a plurality of perspectives.”

The authors provide a framework for navigating tensions and power dynamicsamong diverse actors

to create broad ownership for different types of co-production processes.

A lot of attention has been given tothe concepts of scaling up andscaling out, butany bottom-up

transformation process is likely to encounter active resistance by those with power and there is limited

understanding of how to work within and across scales to break down such resistance.

The constructive exploration of tensions and conflict is increasingly recognized as a catalyst for social

learning and transformation. These concepts move beyond ‘defensive’ approaches to managing

tensions, to a willingness to understanddifferent positions and agendas as complex

interdependencies rather than competing interests, where the primary purpose of a discourse is not

to seek consensus and resolve tensions, but rather to learnto “stay with the trouble”of difference

and the discomfort it brings.

In the review the authorsfound that co-production initiatives were constantly challenged to find a

middle space between and within creating space for all views, yet also bringing a critical angle and by

not unjustly imposing agendas, but also not romanticizing others’ agendas. They found that fostering

such agility among these roles depended on creating processes that weave together and balance

power amongboth critical and solution-oriented perspectives. The way the authorsconceptualized

fourpathways for co-production and the six processes to navigate these pathways, is shown in the

diagram below.

14

Figure 2: Critical processes to foster co-productive agility in each of the four pathways to sustainability transformations

These concepts have been developed to mitigate againstthe well-known experience where research

and practice may spend too much time debating which agenda for change is best, and too little time

considering how to facilitate betterinteractions among different agendas. The tendency to close down

debate over co-production agendas and cover updisagreements for the sake of convenient consensus

is linked to the standards of “success” by whichscientists and practitioners are held accountable,

alongside pressure to show immediate tangible outcomes. According to the authors, such time

pressure can incentivize the rapid creation of large ‘inclusive’ multi-stakeholder platforms; yet co-

productively agile initiatives consistently limitedparticipation in important ways to effectively balance

powerrelations. They found that embedding research into practice moved initiatives into spaces of

co-productive agility. Enabling cognitive, relational, and organizationalaspects of co-productive agility

may therefore necessitate shifts in institutional environments and funding criteria, to recognize the

value of processes thatcarefully and iteratively navigate tensions and cultivate safe spaces (Chambers,

et al., 2022).

These perspectives provide valuable insight and design options towards developing appropriate

spaces for co-creation across disparate role players with differing agendas, within this research brief.

Aspects of this analysis are to be considered within a number of the related work packages

/deliverables within this research process.

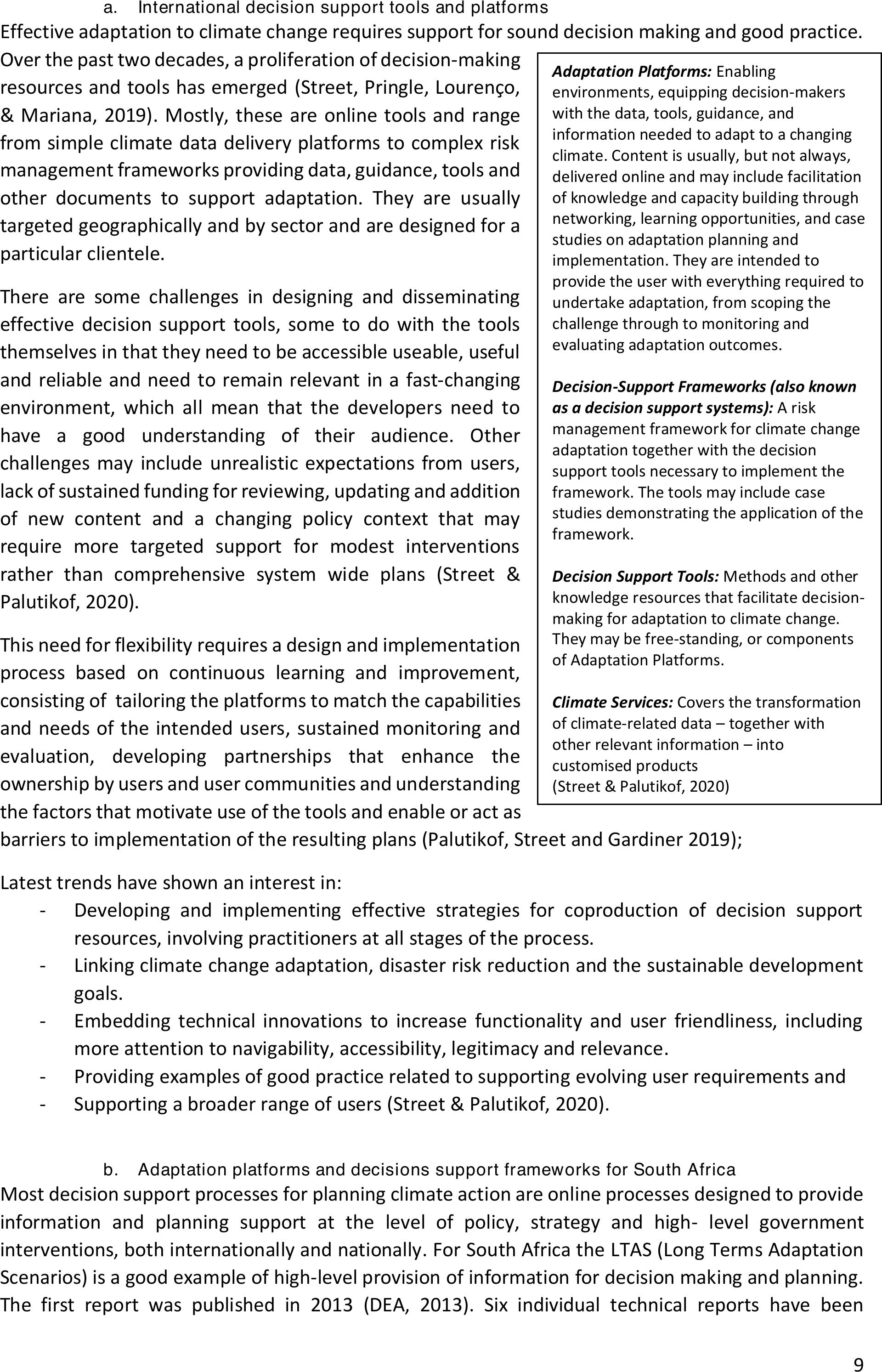

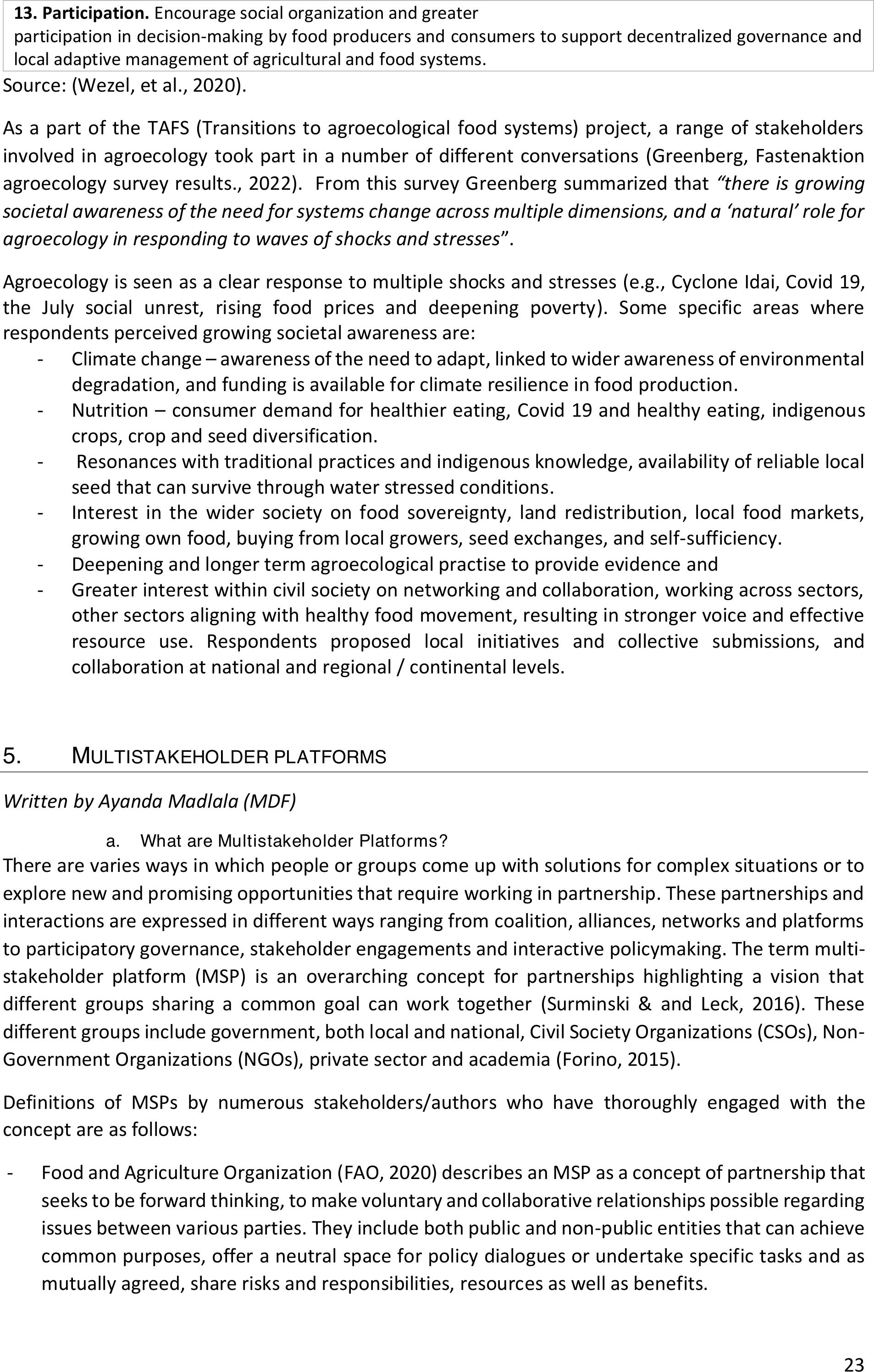

c.Vulnerability assessments

As with decision support resources a wide range of global and nationalrole players have developed

and proposed frameworks and tools. Vulnerability assessments are the first step towards framing the

context forimplementationofadaptation measures, especially within the broader understanding that

building of resilience requires longer term, participatoryand holistic approaches, rather than purely

technical, short- term responses, to address allof theunderlying structural vulnerabilities in our

society.

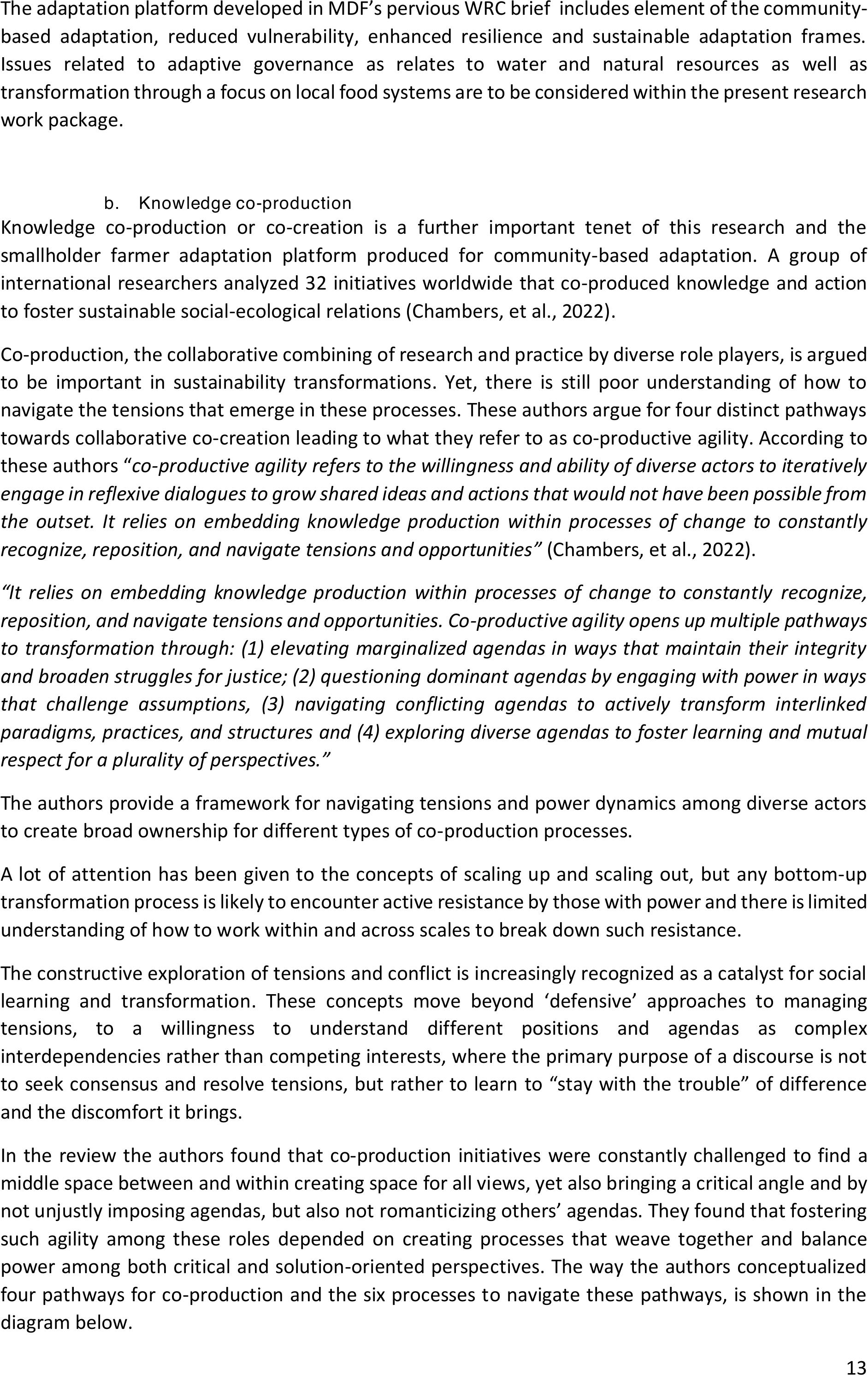

Understandably, the developed frameworks are thus quite complex and comprehensive and require

considerable capacity and resources to undertake.In most cases, the level of vulnerabilities was

determined using the IPCC endorsed framework (Exposure + sensitivity = Potential Impact + Adaptive

capacity = Vulnerability).

15

Figure 3:The component of climate

vulnerability and climate risk, adapted from

IPCC AR5 ( (GIZ, with EURAC and Adelphi,

2017).

In South Africa, the National Risk and

Vulnerability Framework (NRVF) is

intended to provide an overarching

approach and guidance towards

undertaking risk andvulnerability

assessment using asuite of available

methodologies and tools.

It intends to provide

stakeholders/decision makers with an

integrated diagnostic framework that

can assist to analyse if and how the dynamics of climate

risk is addressed in practical assessment cases, and to also

enhance a common approach/ a shared responsibility

approach in conducting climate risk assessments across all

sectors and to provide decision makers with a selection of

methods and tools to assess the different components

that contribute to key questions such as the type of

planning required for a vulnerability assessment, which

tool to use and how to carry out a vulnerability assessment

(DEFF, 2020).

“The need for this framework stems from the mounting set

of demands for various public, private and non-

governmental organisations to undertake climate risk and

vulnerability (CRV) assessments for policy, planning,

funding, insurance and compliance reasons. These include

requirements under the National Climate Change

ResponsePolicy (2011), the Climate Change Bill, the

National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy andthe

Disaster Management Amendment Act 16 of 2015, as well

as international funding processes and reporting under the

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC)”(DEFF, 2020).

The variety of assessments being undertaken by a range of

organisationshas proved problematic for evaluating

assessments and for aggregating across them to inform planning and decision making at larger scales

and higher levels of governance, underpinning the need for this framework.

Vulnerability: The degree to which someone or

something can be affected by a particular hazard

(from sudden events such as a storm to long-

term climate change).

Vulnerability depends on physical, social,

economic and environmental factors and

processes.

-Physical vulnerability relates to the built

environment and may be described as

“exposure”

-Social vulnerability is caused by such things as

levels of family ties and social networks literacy

and education, health infrastructure, the state of

peace and security

-Economic vulnerability is suffered by people of

less privileged class or caste, ethnic minorities,

the very young and old etc. They suffer

proportionally larger losses in disasters and have

limited capacity to recover. Similarly, an economy

lacking a diverse productive base is less likely to

recover from disaster impact which may also lead

to forced migration

-Environmental vulnerability refers to the extent

of natural resource degradation, such as

deforestation, depletion of fish stocks, soil

degradation and water scarcity that threaten

food security and health. (IFRC, 2007)

16

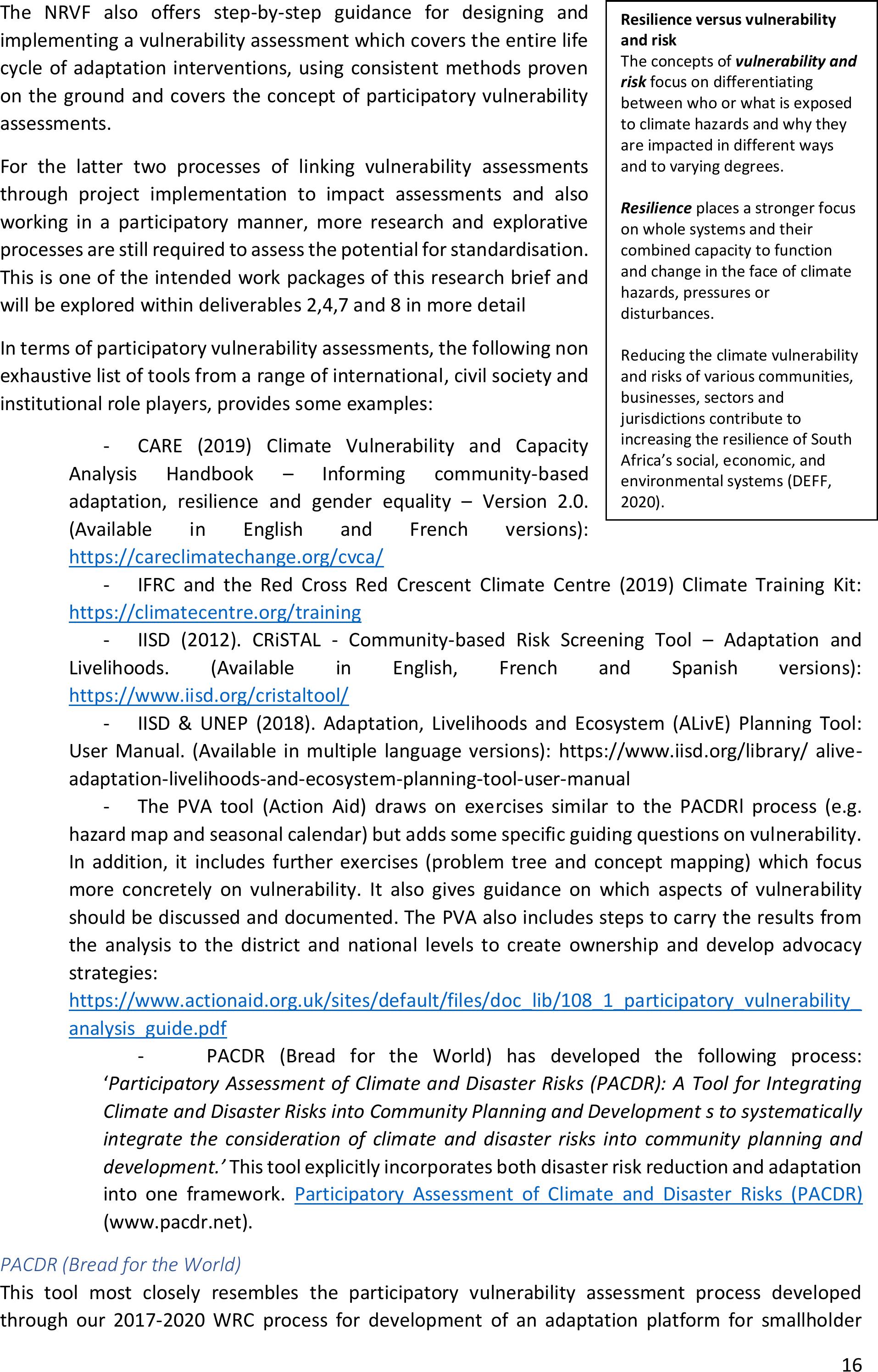

The NRVF also offers step-by-step guidance for designing and

implementing a vulnerability assessment which covers the entire life

cycle of adaptation interventions, using consistent methods proven

on the ground and covers the concept of participatory vulnerability

assessments.

For the lattertwo processes of linking vulnerability assessments

through projectimplementation to impact assessments and also

working in a participatory manner, more research andexplorative

processes are still required to assess the potential forstandardisation.

This is one of the intended work packages of this research briefand

will be explored within deliverables 2,4,7 and 8 in more detail

In terms of participatory vulnerability assessments, the following non

exhaustive list of tools from a range of international, civil society and

institutional role players, provides some examples:

-CARE (2019) Climate Vulnerability and Capacity

AnalysisHandbook –Informing community-based

adaptation, resilience and gender equality –Version 2.0.

(Available in English and French versions):

https://careclimatechange.org/cvca/

-IFRC and the Red Cross RedCrescent Climate Centre (2019) Climate Training Kit:

https://climatecentre.org/training

-IISD (2012). CRiSTAL -Community-based Risk Screening Tool –Adaptation and

Livelihoods. (Available in English, French and Spanish versions):

https://www.iisd.org/cristaltool/

-IISD & UNEP (2018). Adaptation, Livelihoods and Ecosystem (ALivE) Planning Tool:

User Manual. (Available in multiple language versions):https://www.iisd.org/library/ alive-

adaptation-livelihoods-and-ecosystem-planning-tool-user-manual

-The PVA tool (Action Aid) draws on exercises similar to the PACDRl process (e.g.

hazard map and seasonal calendar) but adds some specific guiding questions on vulnerability.

In addition, it includes further exercises (problem tree and concept mapping)which focus

more concretely on vulnerability. It also gives guidance on which aspects of vulnerability

should be discussed anddocumented. The PVA also includes steps to carry the results from

the analysis to the district and national levels to create ownership and develop advocacy

strategies:

https://www.actionaid.org.uk/sites/default/files/doc_lib/108_1_participatory_vulnerability_

analysis_guide.pdf

-PACDR (Bread for the World) hasdeveloped the following process:

‘Participatory Assessment of Climate and Disaster Risks (PACDR): A Tool for Integrating

Climate and Disaster Risks into Community Planning and Development s to systematically

integratethe consideration of climate and disaster risks into community planning and

development.’This tool explicitly incorporates both disaster risk reduction andadaptation

into one framework. Participatory Assessment of Climate and Disaster Risks (PACDR)

(www.pacdr.net).

PACDR (Bread for the World)

This tool most closely resembles the participatory vulnerability assessment process developed

through our 2017-2020 WRC process for development of an adaptation platform for smallholder

Resilience versus vulnerability

and risk

The concepts of vulnerability and

risk focus on differentiating

between who or what is exposed

to climate hazards and why they

are impacted in different ways

and to varying degrees.

Resilience places a stronger focus

on whole systems and their

combined capacity to function

and change in the face of climate

hazards, pressures or

disturbances.

Reducing the climate vulnerability

and risks of various communities,

businesses, sectors and

jurisdictions contribute to

increasing the resilience of South

Africa’s social, economic, and

environmental systems (DEFF,

2020).

17

farmers in South Africa (Kruger, 2021). As this tool is also actively being promoted in South Africa, the

respective organisations have agreed toexplore commonalities and future reviews and adaptations

to these respectivetools through theAdaptation Network Vulnerability Assessments Webinar and

follow up process (About - The Adaptation Network), planned for 2022-2023.

The idea behind the tool is that communities can apply their local knowledge incombination with

general knowledge related to disasters and climate change in a way that suits their specific needs and

situation. The tool provides a simple, easy-to-use structure and guidance to follow in the step-by-step

development of a community assessment of climate and disaster risks and opportunities. It has been

developed over roughly 10 years and has been tested and implemented in Africa, Asia andLatin

America. The assessment can then inform ongoing or planned projects and programmes, and, more

generally, community planning.The tool relieson localparticipation to identify hazards, to prioritize

risks and to develop the strategies necessary to respond effectively to the risks (BfdW, 2020).

More specifically, the tool enables users to:

-Understand how climate and other hazards affect lives and livelihood resources

-Learn how local people currently respond to these hazards

-Identify adaptation strategies to strengthen thethreatened livelihood resources and to

enhance people’s resilience and

-Include gender considerations throughout the assessment of climate and disaster risks.

The PACDR tool consists of7 modules:

1.Context: Preparation of background material and compilation of information on the community–national policies

(CC and DRR), CC information and information on appropriate adaptive responses. (What changes in weather

patterns have occurred, what hazards, what impact and how were different people and livelihoods affected).

2.Climate change and hazard analysis: Participatory mapping, seasonal calendar, prioritization of hazards

3.Vulnerability assessment: Vulnerability matrix

4.Response to the impacts of hazards: Survey and assessment of local response

5.Adaptation strategies: review of CC scenarios, Identification of community adaptation goals, strategies (obstacles

and opportunities)

6.Co-benefits of adaptation strategies: Matrix

7.Community adaptation and planning: Action plan - Identification of activities for individuals,

groups, community and other stakeholders, advocacy plan, presentation to the wider community (BfdW, 2020).

Already one area of cooperation lies in the better integration of the PCDR tool into implementation

and impact assessment processes- an area wherein the WRC developed tool is stronger.

Adaptation and disaster risk management

More and more these two areas are being considered jointly, despite the distinct and different policy,

strategy development and government implementation trajectories.

A multi stakeholder thinktank developed a policy brief (Dept of Env Sci Rhodes uNiversity, 2017) with

the following 6 key messages:

1.The extreme weather events that have dominated the news in 2017 are what we can expect

to see under climate change. Drought, storms, fires and floods will become more frequent and

more intense, giving rise to the expression 'the new normal'.

2.Climate change and weatherevents cannot cause disasters in isolation. A disaster occurs when

extreme weather events collide with impoverished communities, dysfunctional governance

and poorly maintained infrastructure.

3.There are two spheres of discourse dealing with theresponse to extreme hydro-

meteorological events - Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and Climate ChangeAdaptation (CCA).

18

There is overlap in the theory and policy dimensions of DRR and CCA, but little actual

integration of decision making, governance and practice, especially at the local level.

4.The bureaucratic challenge of defining and declaring a 'disaster' often leaves the most

vulnerable either without much needed support or support that comes too late.

5.Technical fixes and emergency responses are not enough on their own, and sometimes make

things worse.

6.Building resilience and preparing adequately forclimate related disasters requires

transdisciplinary, trans-institutional, trans-sectoral approaches, that clearly identifythe

synergies between CCA and DRR.

These policy recommendationsstill hold and are in fact more urgent five years down the line. A recent

review of factors hindering effective integration revealedchaotic institutional arrangements, unlinked

stakeholder activities, lack of political will, haphazard nature of funding, and interrupted knowledge

transferas the critical factors that hinder the integration of CCA and DRR around the globe(Dias,

Amaratunga, Haigh, Clegg, &Malalgoda, 2021). Best practice includes among other factors, risk

assessments which include disaster and climate risks, vulnerabilities and coping capabilities and

considering systemic interlinkages and dependences.This will be kept in mind in further activities

involving the design of vulnerability assessments and monitoring process.

d.Adaptive Management

Adaptive management is not new but has become increasingly relevant in response to rapidly

changing situations, including the COVID-19 pandemic and weather-related disasters. It involves

implementing a management strategy, closely monitoring its effects and then adapting future actions

based on the observed results. In this way, planners simultaneously apply management practices and

learn from those management practices.

In brief, adaptive management can be broken into six general steps:

1.Assess the current conditions; identify any problems; determine goals

2.Design a management plan that incorporates these goals

3.Implement the management plan

4.Monitor the impact(s) of the management plan

5.Evaluate the results of the monitoring process and

6.Modify the plan asneeded to respond to changingconditions, as identified through the

monitoring and evaluation process.

Adaptive management is a cyclicalprocess, running continuously through these steps. The first two

steps involve establishing goals for the management process, while steps three through five represent

the actual implementation and evaluation of the process. In practice, many adaptive management

plans run through steps 3-6 several times before returning to steps 1 and 2, which may involve a

reassessment of the entire management plan, including target goals. It is important to evaluate results

and modify management strategies as needed to respond to changing conditions (Land Trust Alliance,

2021).

Adaptive management involves continually monitoring a process to evaluate its effectiveness, and

improving the process based on this evaluation. It requires transparent planning systems and

implementation strategies, and a strong emphasis on monitoring and reviewing to ensure emerging

information is reflected in future planning (Rogers & Macfarlan, 2020)

19

This methodology is to be used in one of the multi stakeholder platforms within which the research

team is involved namely the Living Catchments Project (SANBI and WRC) in the uThukela River

Catchment. The project has the aim of establishing better-CoPs that are involved with managing the

built and ecological infrastructure within important water catchments.

Stakeholders inthe upper uThukela are working together towards a shared vision of equitable and

sustainable water resources management in the catchment. Warmly welcomed by Okhahlamba Local

Municipality Manager, Nkosingiphile Malinga, on 14th June 2022, almost 40 stakeholders who live,

work or have an interest in the water resources in the upper uThukela catchment, met in Bergvillefor

a one-day Adaptive Planning Process (APP) workshop. This second multi-stakeholder engagement

built on the first workshop of the Living Catchment Project in the upper uThukela in May 2021 and

included a structured process to collaborate towards creating a shared vision between a wide and

diverse range of stakeholders (Letty, 2022).

The APP process is to be continued under this research brief; more specifically under deliverables 4

and 9.

e.Local Food Systems

Food systems has developed as an area of enquiry that explores the political economy of theagri-food

system and focuses on food security and food sovereignty, highlighting issues of agriculture, nutrition

and health related to the food system. This work in South Africa

has been spearheaded by the Southern Africa Food lab since 2009

(Southern Africa Food Lab | Food Security Initiative).

A systematic literature review looking at the future of South

Africa’s food system was undertaken in 2014 (Pereira, 2014).

Food security is the outcome of a complex interaction of multiple

factors on multiple levels, from the production of food to its

consumption, including elements of food availability, food access

and food utilisation. A sustainable food system is regarded as one

that takes into consideration environmental, social and economic

impacts and that provides nutritious food for all.

The concept of the ‘nutrition transition’ has become aconcern in

the food system, especially in developing countries, which is

related to overconsumption ofrefined foods and meatin South

Africa this transition is causing undernutrition in young children

and overweight and obesity in older children and adults(Pereira,

2014).

According to Pereira, “poorer South Africans, especially in rural

andinformal urban areas, are less ableto afford healthy, nutritious

meals on a daily basis. An increasing reliance on purchasing food

instead of growing it has also meant that consumers are more vulnerable to price shocks. In the poor

rural areas the emphasishas shifted from growing one’s own food to buying it at local stores and

supermarkets, often with money received from social grants”. In general, nutrient-dense foods such

as lean meat, fish, fruit and vegetables cost far more than processed food products, further skewing

consumption towards these types of food.

The South African food system has been radically altered by the effects ofrapidurbanisation, the

globalisation of the food trade and the subsequent concentration of agribusiness. Climate change and

Food security is when all people,

at all times, have physical,

social and economic access to

sufficient, safe and nutritious

food that meets their dietary

needs and food preferences for

an active and healthy lifestyle.

Food sovereignty is the right

of each nation to maintain and

develop its own capacity to

produce foods that are crucial

to its own food security, while

respecting cultural diversity and

diversity of production methods.

A local food system is a

collaborative network that

integrates sustainable food

production, processing,

distribution, consumption, and

waste management to enhance the

environmental, economic, and

social health of a particular area.

20

weather variability, water scarcity, a failing land reformprocess, depletion of fish stocks and food

waste pose the biggest threats to the SouthAfrican food system. The duality of the current agriculture

system, where large commercial farmsproduce food for the formal value chain and smallholders are

marginalised is another important concern, which has undermined our food system’sability to provide

livelihoods and has accelerated and deepened the processes that are driving poor people off the land

and fuelling rapid urbanisation.

According to Pereira ‘anoverarchingtheme in many of the papers in the review was the need for multi-

stakeholder engagement in the governance of the food system. The food system isbeing contested on

manylevels and by many different groups. What is generally being advocated is the need to bring

various points of view together to chart a way forward for a food system that is both sustainable and

equitable’(Pereira, 2014).

Greenberg and Drimie state in their review that ‘in summary, the South African food system is highly

contested with the legacy of apartheid leaving a dualisticagrarian system. Theadvent of democracy

coincided with rapid liberalisation of the agricultural sector leading to the consolidation of larger

players including agri-businesses, food processors, retailers and other actors in the food value chain.

Green Revolution approaches to smallholder support have become the dominant paradigm with

powerful actors supporting and entrenching this throughout the food system. As such, agroecology

largely has been marginalised. Despite this, important initiatives, particularly those led by civil society,

have emerged to advance an agroecological agenda. Pockets have alsoemerged within government

(in particular in DALRRD and DFFE) who are willing to support this agenda” (Greenberg & Drimie, The

state of the debate onagroecology in South Africa. A scan of actors, discourses andpolicies. Final

Report, 2021).

In a recentreport, looking at sustainable and inclusivetransformation of the South African food

system (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS).,

2022), four core challengeshave been identified for the country to transition towards asustainable

food system: Improved nutrition; sustainable agricultural production systems; levelling the food

system playing field, and improved food system governance.

Policy recommendations made in this report are:

-In food insecurityand nutrition: reducethe cost of nutrition dense food and increase the

range, scale, and coverageof child-centred food system interventionsin the built environment

-In food production: support the transition towards agroecological food systems, and link land

reform with place-based farmer support

-In market functioning:reform and enforce food system regulatory policies,adopt an

integrated approach to building an inclusive food system and

-In food system governance: improve inclusivestakeholderparticipation and enhanced

engagement and adopt a two-pronged place- and issue-based approach to food system

governance.

It is within this context that promotion of local food systems using sustainable production and land

use practices is being promoted primarily through thecivil society sector with some private and

academic partners. Concepts such as community food systems, local food economies and food

sovereignty are coming into play, linking intothinking around just transitions and transformation of

the food system. In terms of food production agroecology and regenerative agriculture are being

promoted.

21

f.Agroecology

Agroecology is a way of redesigning food systems, from the farm to the table, to achieve ecological,

economic, and socialsustainability. Through transdisciplinary, participatory, andchange-oriented

research and action, agroecology links together science, practice, and movements focused on social

change.

Greenberg and Drimie conclude that ‘given the reality of agricultural practice in South Africa, the wide

range of existing definitions of agroecology canbe considered as aspirational. As such, the accent is

placed on diverse ecological production techniques and their integration at farm andlandscape levels.

We propose these be considered as acontinuum of practices, with “entry level” requirements for

stepping onto the path ofagroecology as no use of genetically modified (GM) seeds, synthetic fertilizers

or pesticides that are toxic to humans, animals and the soil. The list of practices offersa range of

opportunities for building change practically from the “grassroots” level. Recognizing agroecology as

a movement, we also propose the integration of participatory methods of dialogue, research,

experimentation and learning as defining features of agroecological practice’ (Greenberg & Drimie,

The state of the debate on agroecology in South Africa. A scan of actors, discourses and policies. Final

Report, 2021).

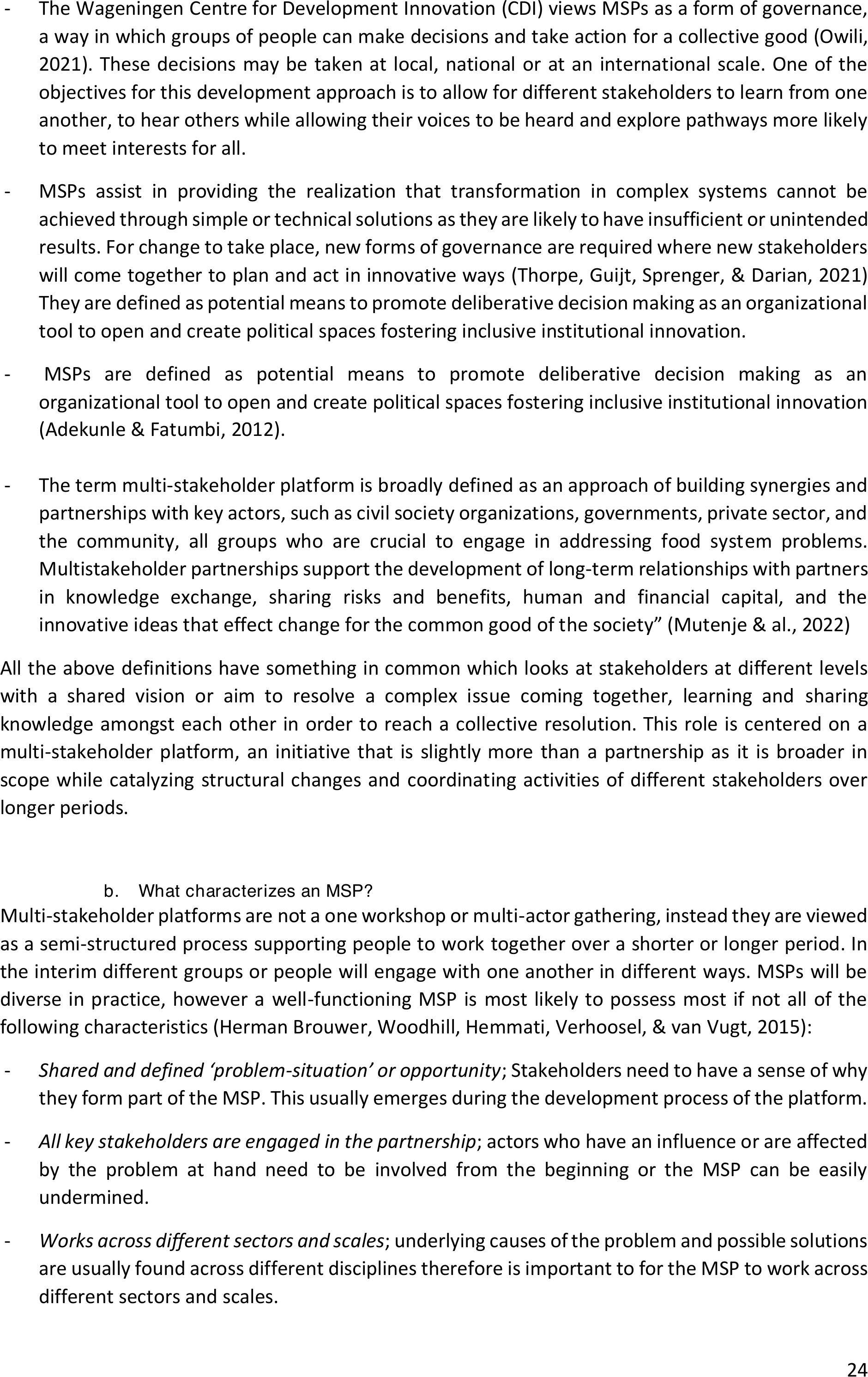

The authors developed a table outlining the main discourses around agroecology in South Africa, as

shown below.

Corporate food regime

Food movements

Neoliberal

Reformist

Progressive

Radical

Food enterprise

Food security

Agroecological practice

Food sovereignty

Core approach based on

food coming from

corporate-industrial

producers.

Key strategies include

increased corporate-led

industrial production;

Green Revolution;

high levels of external

inputs such as fertilisers

and agro-chemicals;

expansion of GMOs;

public-private

partnerships; market

access (especially export

markets).

Small scale producers

(especially those using

natural techniques) are

seen as an anachronism,

otherwise as cheap

labour and land for

production of mass

commodity crops.

Large-scale commercial

agriculture still at the

base of food production

and distribution, but

some role for

smallholder producers

through value chain

integration, some

recognition of

environmental limits and

constraints, especially

water and soil.

Environmental

modernisation /

sustainable

intensification within a

capitalist market context

(e.g. CA/CSA).

Diverse viewson

agroecology/organic

production from within

the reformist group:

i) Organics as a premium

niche market

ii) Natural farming as a

hobby but notfor bulk

production

iii) Agroecology is

equated with

subsistence production /

Core approach based on

food coming from an

open set of dynamic and

interconnected practices

on a continuum from a

set of “entry level”

practices to integrated

systems at farm,

landscape and territorial

levels.

Core/entry level

practices are no GM

seeds;use of only

organic/natural soil

fertility methods; and

use of only

organic/biological pest

management and

controls.

Key role for smallholder

production and small

enterprises throughout

supply systems.

Sustainable food

systems, fair and short

distribution networks,

food systems embedded

in local economies.

Social and ecological

integration, popular and

Core approach sees food

coming from

agroecological practice

based on organised

collective agency and

democratic control of

food systems.

Radical nature of

approach characterised

by radical redistribution

of land and other

resources, active

organised resistance to

corporate and other

extractive encroachment

/ occupation of

agricultural, foodand

wider systems.

22

‘traditional’ / backyard

agriculture or homestead

gardening with a welfare

and poverty relief

emphasis.

indigenous knowledge,

key role for women, right

to food.

Collective and

participatory practices.

A trend in the food movement is towards practice “in the shadow of policy” with efforts to work

‘beyond’ the state in thecontext of state capture and lack of responsiveness. Recent literature

details how embedded this form of corruption facilitated by powerful figures withinthe state has

been and how state capture has exacerbated institutional decay. State capture has undermined

the social contract that was intended at the advent of democracy in 1994 (Greenberg & Drimie,

The state of the debate on agroecology in South Africa. A scan of actors, discourses and policies.

Final Report, 2021).

Principles for implementation of agroecology have been defined by theFAO andthe United

Nations HLPE (Wezel, et al., 2020). These are shown in table format below

Principle

FAO’s ten elements

Improve resource efficiency

1. Recycling. Preferentially use local renewable resources and close as far as

possible resource cycles of nutrients and biomass

Recycling

2. Input reduction. Reduce or eliminate dependency on purchased inputs

and increase self-sufficiency

Efficiency

Strengthen resilience

3. Soil health. Secure and enhance soilhealth andfunctioningfor improved plant growth, particularly by

managing organic matter and enhancing soil biological activity.

4. Animalhealth.

Ensure animal health and

welfare

5. Biodiversity. Maintain andenhance diversity of species, functional

diversity and genetic resources and thereby maintain overall agroecosystem

biodiversity in time and space at field, farm and landscape scales.

Part of diversity

6. Synergy. Enhance positive ecological interaction, synergy, integration and

complementarity among the elements of agroecosystems (animals, crops,

trees, soil and water)

Synergy

7. Economic diversification. Diversify on-farm incomes by ensuring that

small-scale farmers have greater financial independence and value addition

opportunities while enabling them to respond to demand from consumers.

Part of diversity

Secure social equity/responsibility

8.Co-creation of knowledge. Enhance co-creation and horizontal sharing of

knowledge including local and scientific innovation, especiallythrough

farmer-to-farmer exchange.

Co-creation and sharing of

knowledge

9. Social values and diets. Build food systems based on the culture, identity,

tradition, social and gender equity oflocal communities that provide healthy,

diversified, seasonally and culturally appropriate diets.

Parts of human and social

values and culture and food

traditions

10. Fairness. Support dignified and robust livelihoods for all actors engaged in food systems, especially small-

scale food producers, based on fair trade, fair employment and fair treatment of intellectual property rights.

11. Connectivity. Ensure proximity andconfidence between producers and

consumers through promotion of fair and short distribution networks and by

re-embedding food systems into local economies.

Circular and

solidarity economy

12. Land andnatural resource governance. Strengthen institutional

arrangements to improve, including the recognition and support of family