GOVERNANCE CONSIDERATIONS

BACKGROUND

Governance relates to how water supply, access, availability and useis managed at individual,

local and institutional levels.

The GLSCRP focusses both on technical design as well as local level and institutional options for

improved management and maintenanceof built infrastructurein a changing climate. Aspects

of integrated water resources management at a village and catchment level are also

important.In general, demand for water is increasing while the environment’s ability to

supply water is decreasing- and ata rate muchfaster than can easily be accommodated.

Management of catchments and recharge areas is crucial, but presently not well considered.

To date the process has entailed provision of water access and infrastructure through mandated

government institutions, with an expectation of care, management and maintenance by the

beneficiaries. How this is meant to happen however, has not received a lotof attention.

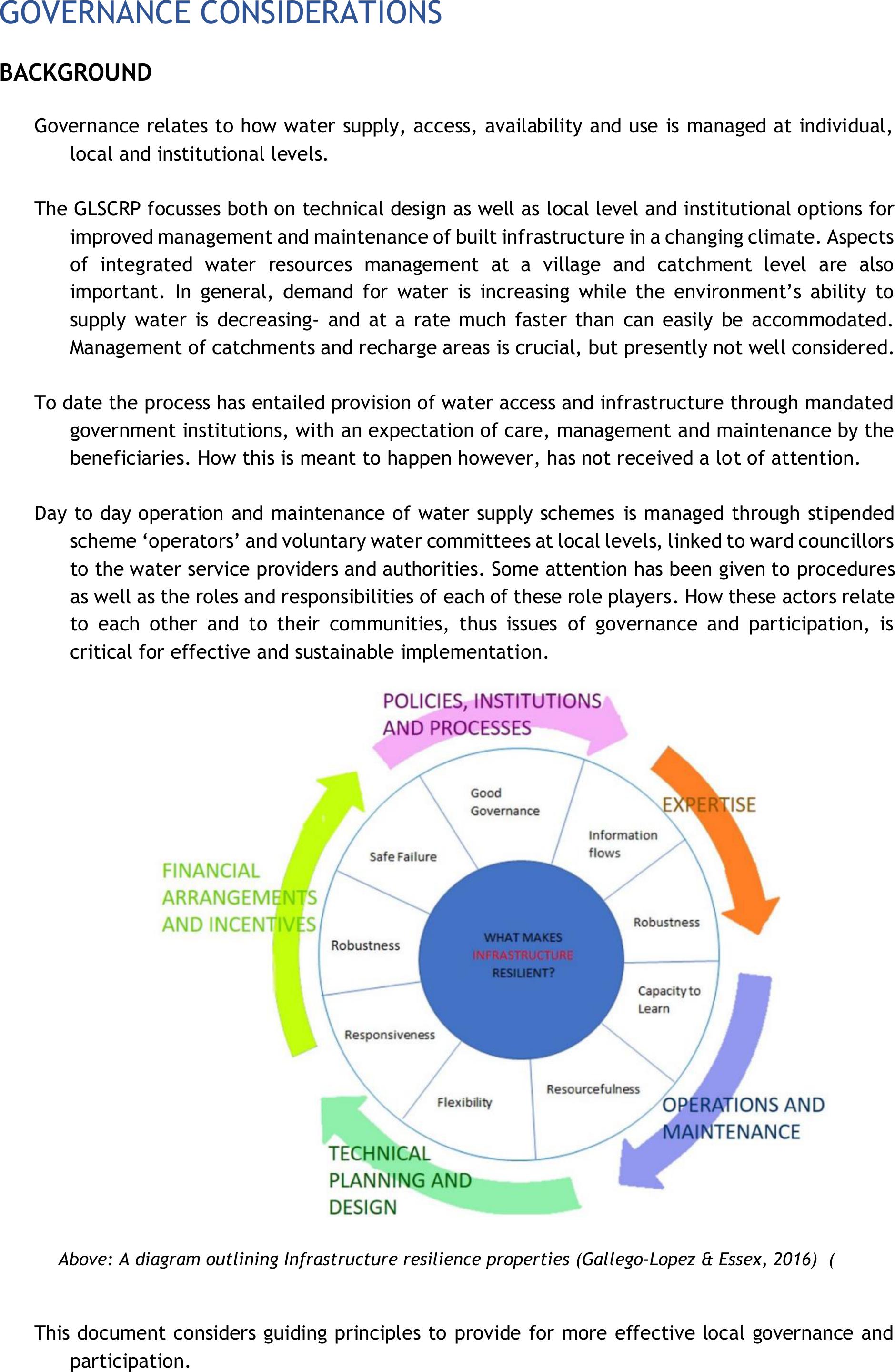

Day to day operation and maintenance of water supply schemesis managed through stipended

scheme ‘operators’and voluntary water committees at local levels, linked toward councillors

to the water service providers and authorities. Some attention has been given to procedures

as well as the roles and responsibilities of eachof these role players. How these actors relate

to eachother and to their communities, thus issues of governanceand participation, is

critical for effective and sustainable implementation.

Above: A diagram outlining Infrastructure resilience properties (Gallego-Lopez & Essex, 2016)(

This document considers guiding principles to provide for more effective local governance and

participation.

COMMUNITY LEVEL INVOLVEMENT

All members of a community are expected to make use of provided infrastructure and water

access in a responsible manner. For this to be possible all community members needto:

•be considered in terms of their needs,

•be informed about the technical aspects of operation for the system,

•understand the implications and limits of access and availability of water,

•know and agree to the management and operational confines of the system and

•be willing to follow the rules set in place for quality, management and use of water.

The above can only happen if every single member in the community takes some individual

responsibility and considers the impact of their actions on their neighbours and community.

In largerand more urban communities, individual behaviour is controlled primarily through

payment for specific services and access, with associatedregulations. In rural and informal

communities, this system of control does not exist. This can lead to high levels of inequity,

competition, abuse, and mismanagement of water supply systems.

The temptation is to attempt to enforce payment andregulation of services. Thesolution

however, lies more in the full participation of all community members in every phase of the

process.

GUIDELINES FOR COMMUNITY LEVEL ENGAGEMENT

Community members need to be engaged in initial baseline, vulnerability and feasibility

assessments for proposed water supply schemes.

Community members need to understand water access options, water sources and availability and

water use implications fortheir village.

Community members need to be provided with information to be able to assess the proposed

scenarios for development of water access options.

Community members need to be provided space for learning and analysis of concepts related to

water management in their areas, including for example climate change impacts, rainfall and water

infiltration, groundwater and groundwater management, water quality for drinking and

multipurpose use, technical aspects of proposed systems, solar energy, water purification options,

water use and conservation etc., so that they are better able to make informed decisions.

Community members need to develop an understanding of water provision as a service with the

potential for different levels and sources of access for different purposes and different levels of

access to this service dependant on financial and other contributions.

In complex programmes scenarios are developed. These are refined in the planning and

implementation and yet further changes can occur during the contractual and commissioning

phases. Expectations are raised in each phase and community members often remember well what

was “promised’ at the beginning. This process requires careful explanation on an ongoing basis.

NOTE: the tendency is to not provide detail or make specific ‘promises’ to avoid the resultant

conflict, but the better practise is to explain the changes and difficulties as the process unfolds,

which despite being a lot more intensive has the advantage of also increasing community level

understanding of the issues and problems involved and this level of transparency builds trust and

rapport between the role players, as well as a level of accountability in expenditure.

Community members need to engage with and negotiate all parameters of the scheme to be able to

take responsibility for further operation, management and maintenance.

Community members need to be involved in decision making on a day-to-day level and in

selection/election of local water governance structures/committees.

They need to be a part of the process of decision making around beneficiation and equity.

ASSUMPTIONS:

It is possible to make some assumptions on how individuals in rural communities will behave, based

on experiences in engaging these communities in designing, planning and implementing local water

access options, rather than being the passive recipients of externally designed and implemented

water supply systems. These experiences have shown that:

•Community members are willing and able to participate.

•Community members are willing to volunteer their time, labour, and money towards ensuring a functional

water system.

•Community members are committed to ensuring that their water supply system is operational and looked

after.

•Community members are willing and able to make rational and considered decisions around water use and

management if provided with appropriate information on which to base such decisions.

•The actual level of involvement in the operation and maintenance of the system is a choice for community

members. Some members participate by voluntarily following the rules and others are more involved in the

management of the system.

•Levels of water access need to be equitable and transparent.

GUIDELINES FOR LOCAL GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES

At community level arrangements are more often than not already in place, although they would be

considered informal. Often these arrangements will not fulfil the requirements of the Water Service

Authorities but provide for a level of stability and equity within the community.

Water committees are voluntary structures and as such have two major weaknesses:

Members do have a certain level authority within the community but are not able to effectively

police any rules. They cannot control or officially/legally enforce anyof the rules agreed to be the

community. As such informal arrangements are developed. Often it relies on community members

contributing in time and in small regular payments to an agreed activity, such as water

infrastructure maintenance or borehole pumping costs for example. The committee keeps records

of those community members who pay and those who do not. Generally, those community members

who resist the rulings or do not pay are considered not to be part of the process and their opinions

or complaints or difficulties are then not taken into account and

Members of committees can take advantage of their authority to improve their own beneficiation,

often justified as a form of compensation for their efforts. This process, if managed in a

transparent way, could actually assist in providing for longer term sustainability of committees, as

it provides some benefit to the committee members who often have to deal with many problems,

conflicts and complaints on an ongoing basis.

At village level this is a manageable beneficiation system and can allow for a stable and ongoing

operational system, without too much conflict. There is however a chance that vulnerable

households and individuals are excluded from a service which should benefit all community

members. Households with very high levels of poverty are moreoften than not also households

where members engage in socially high risk and unacceptable behaviours, which ostracises them

from the rest of the community. Other prejudices may also surface, especially around unmarried

women with children and ‘foreigners. It is proposed that this process be externally facilitated, as it

is unlikely that communities themselves will design d=systems that are fully equitable.

LOCAL WATER COMMITTEES

Care needs to be taken to ensure that these committees are wellrepresented and should include

representation from:

➢The traditional ward councils

➢The Local ward councils (Local Municipality)

➢Local representatives of the Water Service Authority and providers

➢Members form local development structures and interest groups, including for example the

livestock association, development committees, farmers associations and groups,

cooperatives, churches, schools and creches and

➢Local household members; both with access to individual water supply options (like

boreholes and springs) and without.

These committees need well developed constitutions with roles and responsibilities outlined

therein. These committees also need to have arrangements in place for operations and

maintenance of the water service in their village as well as security of infrastructure.

Security concerns for infrastructure are a reality and something that water committees invariably

will need to deal with. Local security arrangements are important and are already being more

commonplace, both for infrastructure and for livestock. In some villages in Giyani, including

Mayephu, 24hr patrols have already been put in place to monitor and control theft. It is foreseeable

that these patrols can also undertake monitoring of the water infrastructure, within the same broad

system. In other villages,households closest to the infrastructure are tasked with ‘keeping an eye’

and are assisted by the water committees, or guards are appointed and provided with a stipend

collected from community contributions.

INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE (O&M)

O&M is sometimes thought to be a simple technical matter that is easy to solve. Yet as the

persistent breakdowns in water supply systems in many villages illustrate, adequate O&M relies on

a surprisingly complex set of organisational functions and competencies. Suitable human resources,

access to theright tools, an inventory of spare parts, reliable transport, mechanisms for reporting

breakdowns, accountability frameworks, and assured, regular funding are all vital (SADC-GMI,

2020).

O&M includes regular tasks such as replacement of worn parts, refuelling, servicing, cleaning and

monitoring, as well as dealing with irregular breakages, outages and malfunctions. Long-term,

successful O&M needs suitably skilled and motivated personnel and depends in turn on a set of

institutional and organisational systems that are viable financially and politically (SADC-GMI, 2020).

There are many factors that determine the quality of O&M. The main ones are quality of staff,

access to dedicated O&M funds, and the quality of records and analysis of information

Technical and operational procedures forongoing management of the water supply systems are

being and should be designed and outlined by the institutional role players in water service

provision. The question here is how communities engage in this activity.

It is assumed by both local beneficiaries and waster service providers that communities can

undertake day to day tasks in operation and maintenance. Community members are the first to

state that they can and already do, undertake simple and low-cost maintenance activities to their

water schemes by themselves. These include actions such as replacing leaking taps, fixing leakages

in pipes and replacing or adding valves. Communities also willingly manage water distribution

aspects, such as switching pumps on and off and opening and closing valves to supply different

sections of their villages with water.

They falter however, where faults are more technical in nature, such as when pumps do not

function well, or break, or when there are faults in the electrical or fuel supply systems.

Replacement of filters and other spare parts are also problematic mostly due to lack of access to

these. Good working relationships with the technical and institutional partners are critical for these

aspects.

The basic principle as outlined already, is that everyone needs to be engaged even if only at the

level of closing running taps or reporting leakages or issues to the water committees and scheme

operators, as well as in following prescribed procedures foraccess. These activities all fall within

corrective maintenance actions and are demand driven, rather than being preventative. For the

latter, a high level of pro-active planning and collaboration between stakeholders is required.

A NOTE ON COST RECOVERY OPTIONS

Sustainable infrastructure projects must generate a sound revenue stream based on adequate cost

recovery and be supported, where necessary, by well - targeted subsidies (to address affordability).

Users’ willingness to pay for O&M and development of suitable tariffs are central to the ongoing

sustainability of a water supply system.

Tariffs usually contain two charges; a charge that depends on the volume of water used and one

that is no e.g. connection fees, ad hoc maintenance fees and the like.

From discussions with local water committees in Giyani, members are confident that monthly fees

from users is an option. The value of such fees should in their opinion not be higher than R20/ user/

month, given that most households in these villages are extremely poor and unemployment levels

are very high. This is clearly not a full cost recovery option but can assist greatly in overall

sustainability.

Regular monthly payments by all households in a village is however logistically problematic,

especially forlarger villages. Generally ongoing financial contributions for groups larger than 20-30

members becomes unwieldy, with high levels of effort spent on policing and the resultant conflicts

often lead to failure of the process. Below are some suggestions of how this can be managed:

➢Monthly contributions by households are recorded by the water committee and those who

do not pay are regarded as non-participants and not supported when they have difficulties

in access. This is an existing system in some of the villages and is accepted and manageable

but has the distinct drawback of excluding vulnerable households.

➢Divide the village into sections with smaller numbers of households and manage monthly

contributions and access per section. In this approach, each section can be provided with a

target value of monthly, weekly or daily financial contributions to allow for access. The

decentralization of this system is a strength, but defaulting can still cause major

difficulties. Cross subsidization for the poorer households is however an option.

➢Use of local savings mechanisms to allow for regular payments. The large majority of rural

households belong to a range of informal savings groups, such as stokvels and funeral

groups. Local savings and loan associations are an extension of this practice, which allows

for improved cashflow and accumulation of funds for specific uses. The strength of these

groups is that they are voluntary and generally well established in rural communities. The

drawback is still that vulnerable households are excluded and that these groups require

some level of external facilitation and policing to remain well managed in the longer term.

Thus, the main question becomes one of how equitability and the right to water can be ensured for

vulnerable households. The logical option is that those households with the ability and resources to

secure larger volumes of water for themselves cross-subsidize those who cannot. This approach

would entail tariffs set at village level related to the volume of water accessed.

A case study to follow on discussion of such options with local water committees and their

responses…

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR WATER SERVICE PROVIDERS AND AUTHORITIES

The full engagement and participation oflocal communities is alsoimpacted by how the water service

stakeholders and institutions interact with them. Below are some broad recommendations for

management of these relationships:

1Local level governance systems need to be respected but also interrogated in terms of

acceptable levels of provision for equity in access to water within the community.

2Engagement of the governance committees and community as a whole in being more equitable

in terms of their access arrangements is important.

3Community engagement needs to be broader than just the committees and operators at all

stages of the discussion: Feasibility, design, implementation, operation and maintenance.

4Committees should be well represented –traditional authorities, local government councillors,

active water users in theareas, such as crop and livestock farmers and individuals whocan

represent more vulnerable groups in the village.

5Institutional engagement in punitive measures for thosewhohave informal orillegal connections

is unlikely to have a positive outcome.

6Hoarding of water and water provision options, by those households which can afford it and have

power within the community should be dissuaded. Here, a userpays arrangement can potentially

be negotiated. At the very least, they should not have more accesstocommunal water than

everyone else in the community.

7Payment for water use in excess of an agreed amount, can be used towards setting up a

community level fund for maintenance and operations.

8Ongoing monitoring of water levels, specifically for boreholeschemes, with a coherent system

of reporting is important.In this respect provision of dip meters will be required. Scheme

operators need to have someone to report to whocan make decisions regarding use, over-use

and remedial actions that can be taken.

References

Gallego-Lopez, C., & Essex, J. (2016). Deisgning for infrastructure resilience. UK: Evidence on

Demand. DFID.

SADC-GMI. (2020). Training manual for operation and maintenance of groundwater infrastructure in

SADC. Bloemfontein, South Africa: SADC-GMI report.