$-*."5&$)"/(&"%"15"5*0/'034."--)0-%&3

'"3.&34*/4065)"'3*$"

70-6.&1"35$0..6/*5:$-*."5&$)"/(&"%"15"5*0/

'"$*-*5"5*0/"."/6"-'03'"$*-*5"5*0/0'$-*."5&3&4*-*&/5

"(3*$6-563&'034."--)0-%&3'"3.&34

77

i

Climate Change Adaptation for

Smallholder Farmers in

South Africa

Volume 2 Part 1: Community Climate

Change Adaptation facilitation: A manual

for facilitation of Climate Resilient

Agriculture for smallholder farmers

Report to the

Water Research Commission

by

E Kruger

Mahlathini Development Foundation

WRC Report No. TT 841/2/20

February 2021

ii

Obtainable from

Water Research Commission

Private Bag X03

Gezina, 0031

orders@wrc.org.za or download from www.wrc.org.za or www.mahlathini.org

The publication of this report emanates from a project entitled Collaborative knowledge creation and

mediation strategies for the dissemination of Water and Soil Conservation practices and Climate Smart

Agriculture in smallholder farming systems. (WRC Project No.K5/2719/4)

This report forms part of a series of 9 reports. The reports are:

Volume 1: Climate Change Adaptation for smallholder farmers in South Africa. An implementation

and decision support guide. Summary report. (WRC Report No. TT 841/1/20)

Volume 2 Part 1: Community Climate Change Adaptation facilitation: A manual for facilitation of

Climate Resilient Agriculture for smallholder farmers. (WRC Report No. TT 841/2/20)

Volume 2 Part 2: Climate Resilient Agriculture. An implementation and support guide: Intensive

homestead food production practices. (WRC Report No. TT 841/3/20)

Volume 2 Part 3: Climate Resilient Agriculture. An implementation and support guide: Local, group-

based access to water for household food production. (WRC Report No. TT 841/4/20)

Volume 2 Part 4: Climate Resilient Agriculture. An implementation and support guide: Field cropping

and livestock integration practices. (WRC Report No. TT 841/5/20)

Volume 2 Part 5: Climate Resilient Agriculture learning materials for smallholder farmers in English.

(WRC Report No. TT 841/6/20)

Volume 2 Part 6: Climate Resilient Agriculture learning materials for smallholder farmers in isiXhosa.

(WRC Report No. TT 841/7/20)

Volume 2 Part 7: Climate Resilient Agriculture learning materials for smallholder farmers in isiZulu.

(WRC Report No. TT 841/8/20)

Volume 2 Part 8: Climate Resilient Agriculture learning materials for smallholder farmers in Sepedi.

(WRC Report No. TT 841/9/20)

DISCLAIMER

This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for

publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of

the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial productsconstitute endorsement or

recommendation for use.

ISBN 978-0-6392-0228-0

Printed in the Republic of South Africa

© WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following individuals and organisations deserve acknowledgement for their invaluable

contributions and support to this project:

Chris Stimie (Rural Integrated Engineering RIEng)

Dr Brigid Letty and Jon McCosh (Institute of Natural Resources – INR)

Nqe Dlamini (StratAct)

Dr Sharon Pollard, Ancois de Villiers, Bigboy Mkabela and Derick du Toit (Association for Water and

Rural Development)

Bobbie Louton

Hendrik Smith (GrainSA)

Marna de Lange (Socio-Technical Interfacing)

MDF interns and students: Khethiwe Mthethwa, Samukhelisiwe Mkhize, Sylvester Selala, Palesa

Motaung and Sanelise Tafa and

MDF board members: Timothy Houghton and Desiree Manicom

PROJECT FUNDED BY

REFERENCE GROUP MEMBERS

Prof S Mpandeli Water Research Commission

Dr S Hlophe-Ginindza Water Research Commission

Dr L NhamoWater Research Commission

Dr O CrespoUniversity of Cape Town

Dr A Manson KZN Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

Prof S WalkerAgricultural Research Council

Prof CJ Rautenbachpreviously of WeatherSA

COLLABORATING ORGANISATIONS

https://www.inr. org.za/https://award.org.za/https://amanziforfood.co.za/

https://foodtunnel.co.za/http://www.rieng.co.za/

iv

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

AEZ Agroecological zone

CA Conservation agriculture

CC Climate change

CCA Climatechange adaptation

CoP Community of practice

CRA Climate resilient agriculture

CSA Climatesmart agriculture

CSO Civil society organisation

DEA Department of Environmental Affairs

DSS Decision support system

NGO Non-government Organisation

OC Organic carbon

PAR Participatory Action research

PIA Participatory impact assessment

PID Participatory innovation development

PLA Participatory learning and action

PRA Participatory rural appraisal

PTD Participatory technology development

RWH Rainwater harvesting

SLT Social learning theory

SWC Soil and water conservation

v

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................iii

PROJECT FUNDED BY ..........................................................................................................................iii

REFERENCE GROUP MEMBERS ........................................................................................................iii

COLLABORATING ORGANISATIONS ..................................................................................................iii

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS.................................................................................................... iv

1PROJECT OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................... 1

2BRINGING TOGETHER THE METHODOLOGICAL ELEMENTS .................................................. 2

2.1LEARNING AND CHANGE..................................................................................................... 2

2.2SOCIAL LEARNING, KNOWLEDGE MEDIATION .................................................................3

2.3AGENCY ................................................................................................................................. 4

2.4SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT........................................................................................................ 5

2.5COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE............................................................................................. 6

2.6INNOVATION SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................ 8

2.7PARTICIPATORY INNOVATION DEVELOPMENT (PID) ...................................................... 9

2.8ADDING THE ELEMENTS TOGETHER: COACTIVE GOVERNANCE IN A CHANGING

CLIMATE ............................................................................................................................... 11

3CLIMATE CHANGE ....................................................................................................................... 12

3.1CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION...................................................................................... 12

3.2CLIMATE SMART / RESILIENT AGRICULTURE................................................................ 13

3.3CONCEPTS OF VULNERABILITY AND RESILIENCE ........................................................ 15

3.3.1VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENTS .................................................................................. 16

3.4SMALLHOLDER FARMING IN SOUTH AFRICA AND CRA ................................................ 17

3.4.1SMALLHOLDER FARMING SYSTEMS............................................................................ 18

3.5LOCAL AND TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE IN CRA........................................................... 20

4DECISION SUPPORT PROCESSES ............................................................................................ 22

4.1WHAT GOES INTO THE CRA SMALL SCALE FARMER DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM ...

.............................................................................................................................................. 22

4.2HOW DOES THE FACILITATOR-FARMER DSS WORK?.................................................. 25

5HOW TO FACILITATE THE FACILITATOR-FARMER DSS ......................................................... 27

5.1BASELINE SURVEY ............................................................................................................. 27

5.1.1THE BASELINE SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE .................................................................. 27

5.1.2EXAMPLE OF A BASELINE SURVEY ............................................................................. 28

5.2COMMUNITY LEVEL CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION ANALYSIS – OUTLINE OF THE

3 WORKSHOPS ................................................................................................................... 29

5.3CCA WORKSHOP 1: CLIMATE CHANGE ANALYSIS – IMPACT AND ADAPTIVE

MEASURES .......................................................................................................................... 30

5.3.1OUTLINE OF THE TWO-DAY WORKSHOP .................................................................... 31

5.3.2FACILITATION TOOLS ..................................................................................................... 35

5.3.3HOUSEHOLD VISITS ....................................................................................................... 42

5.3.4EXAMPLE OF A CCA WORKSHOP1 PROCESS............................................................ 43

5.3.5PRIORITISATION OF ADAPTIVE MEASURES AND PRACTICES ................................. 46

vi

5.4CCA WORKSHOP 2: PRIORITIZATION OF ADAPTATION STRATEGIES AND

PRACTICES.......................................................................................................................... 47

5.4.1OUTLINE OF CCA WORKSHOP 2................................................................................... 48

5.4.2EXAMPLE OF CCA WORKSHOP 2 ................................................................................. 49

5.4.3SEASONAL WEATHER PREDICTIONS .......................................................................... 52

5.4.4FARMER EXPERIMENTATION ........................................................................................ 53

6PARTICIPATORY IMPACT ASSESSMENT (PIA) ........................................................................ 55

6.1BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................... 55

6.2PIA WORKSHOP OUTLINE ................................................................................................. 56

6.2.1RECAP CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ............................................................................ 56

6.2.2RECAP ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES/ PRACTICES............................................................ 56

6.2.3PRACTICES: RECAP FIVE FINGERS AND LIST ALL PRACTICES UNDER EACH

CATEGORY ...................................................................................................................... 57

6.2.4WHAT HAVE BEEN THE CHANGES OR BENEFITS FROM EACH PRACTICE? .......... 57

6.2.5EXPANDING ON PRACTICES ......................................................................................... 57

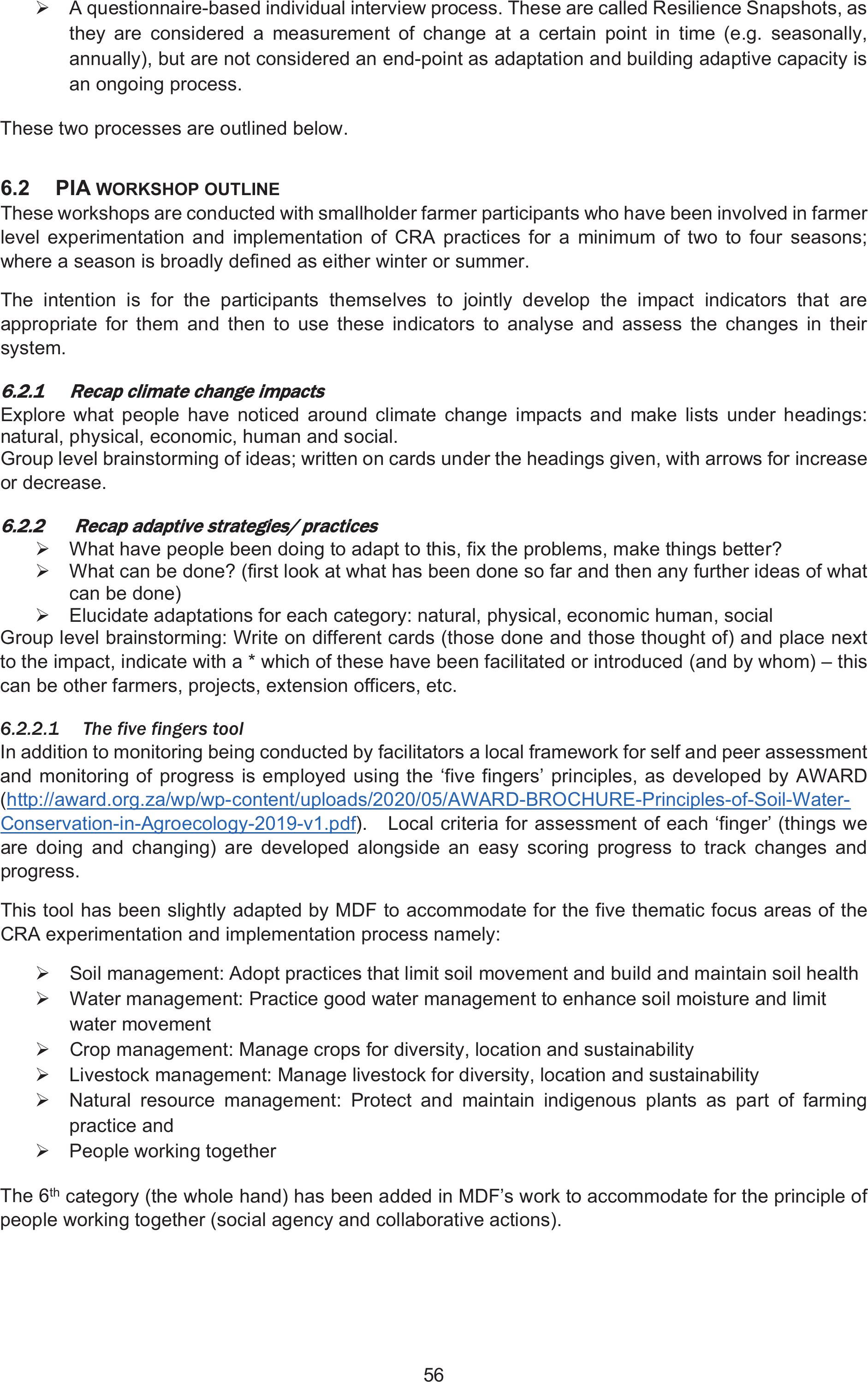

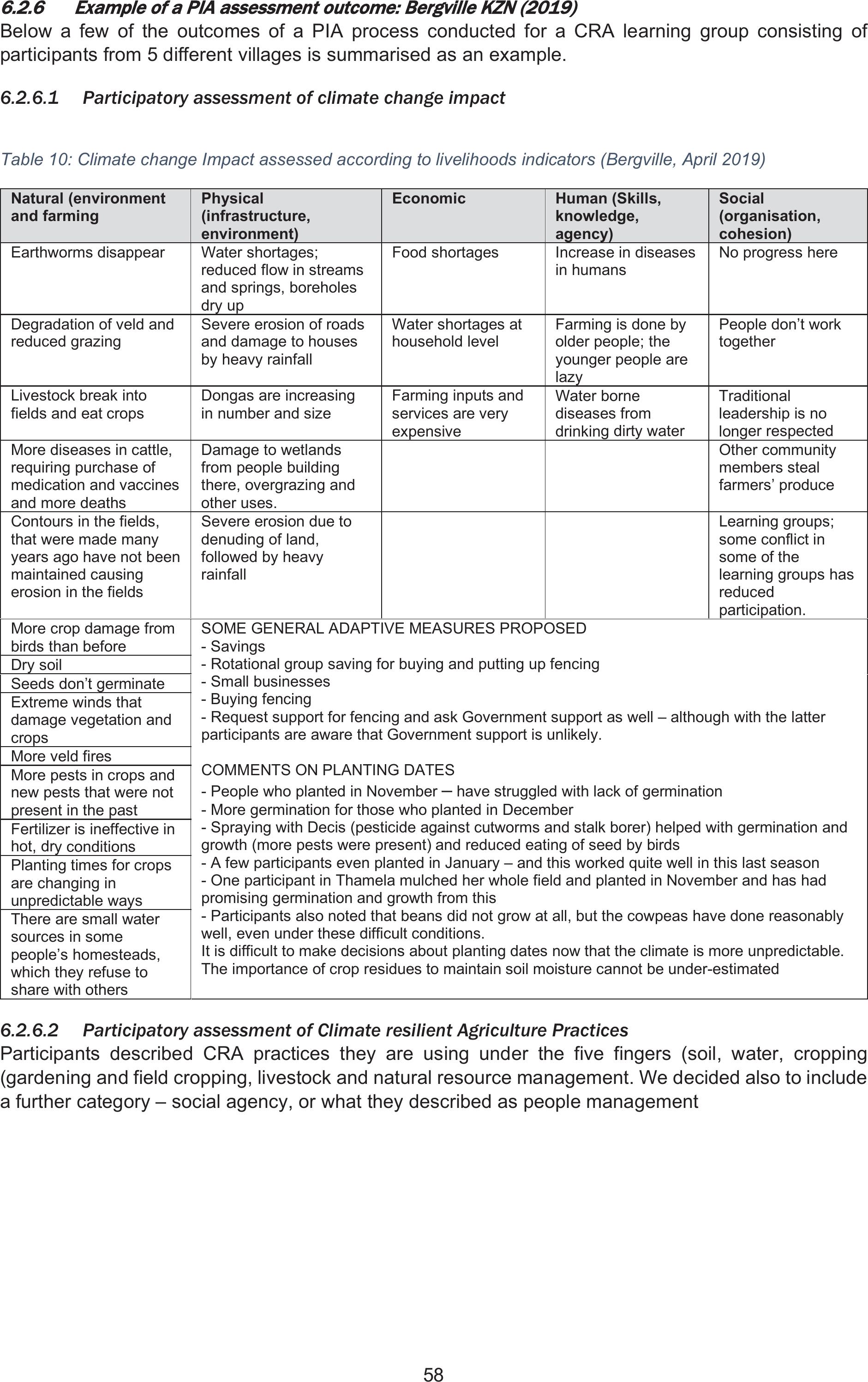

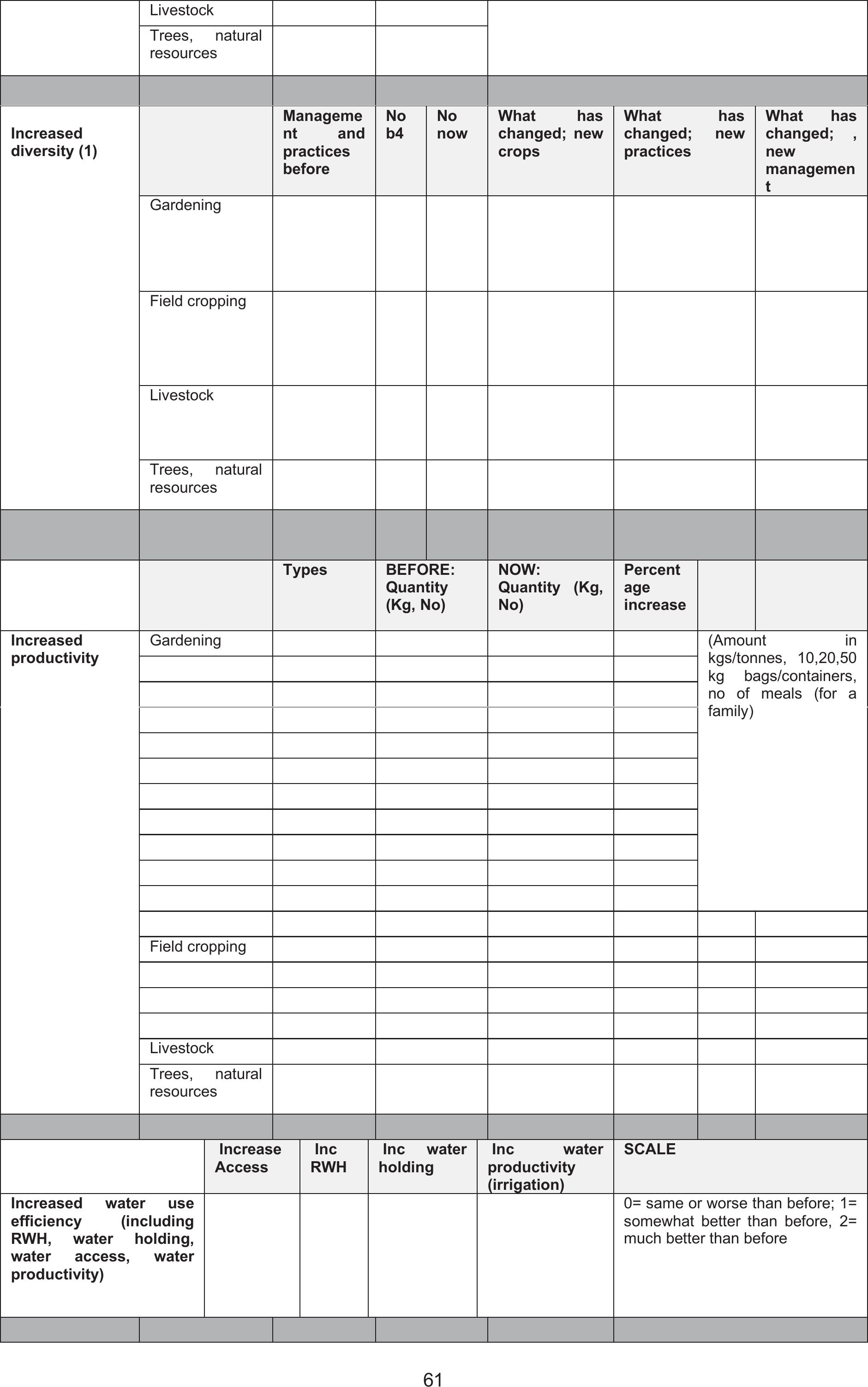

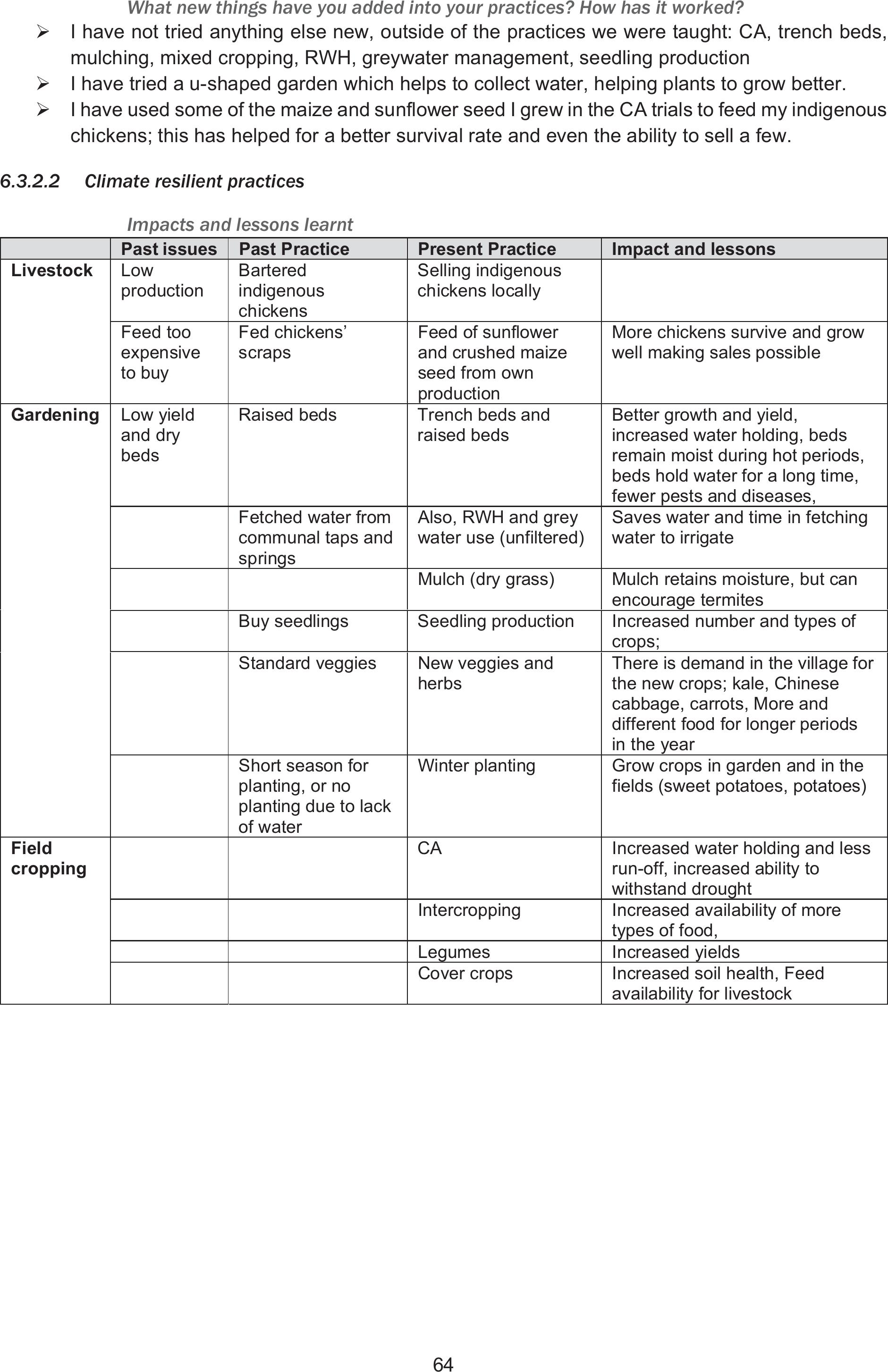

6.2.6EXAMPLE OF A PIA ASSESSMENT OUTCOME: BERGVILLE KZN (2019).................. 58

6.3RESILIENCE SNAPSHOTS.................................................................................................. 60

6.3.1THE INDIVIDUAL CLIMATE CHANGE RESILIENCE QUESTIONNAIRE ....................... 60

6.3.2EXAMPLE OF A RESILIENCE SNAPSHOT ASSESSMENT FOR 12 PARTICIPANTS IN

BERGVILLE, KZN APRIL 2019 ......................................................................................... 63

7REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................. 66

1

Community CCA Facilitation

1 PROJECT OVERVIEW

This facilitation manual is one of the outputs for a Water Research Commission research brief entitled

“Collaborative knowledge creation and mediation strategies for the dissemination of water and soil

conservation practices and climate smart agriculture in smallholder farming systems”, undertaken

between 2017 and 2020.

The research objectives were defined as:

1. To evaluate and identify best practice options for climate resilient agriculture (CRA) and Soil

and Water Conservation (SWC) in smallholder farming systems, in two bioclimatic regions in

South Africa

2. To amplify collaborative knowledge creation of CRA practices with smallholder farmers in South

Africa

3. To test and adapt existing CRA decision support systems (DSS) for the South African

smallholder context

4. To evaluate the impact of CRA interventions identified through the DSS by piloting interventions

in smallholder farmer systems, considering water productivity, social acceptability and farm-

scale resilience

5. To test visual and proxy indicators appropriate for a Payment for Ecosystems based model at

community level for local assessment of progress and tested against field and laboratory

analysis of soil physical and chemical properties, and water productivity.

The design of the decision support system is seen as an ongoing process divided into three distinct

parts:

¾Practices: Collation, review, testing and finalisation of those CRA practices to be included.

This allows for new ideas and local practices to be included over time and also includes linkages

and reference to external sources of technical information around climate change, soils, water

management, etc. and how this will be done

¾Process: Through which CRA practices are implemented at smallholder farmer level. This also

includes the facilitation component, communities of practice, communication strategies and

capacity building and

¾Monitoring and evaluation: Design and implementation of local and visual assessment

protocols for assessing implementation and impact of practices as well as processes used. This

also includes site selection and quantitative measurements undertaken to support the visual

assessment protocols and development of visual and proxy indicators for future use in

incentive-based support schemes for smallholder farmers.

This manual focusses on the process; the methodological and facilitation components of the research

brief.

2

2 BRINGING TOGETHER THE METHODOLOGICAL ELEMENTS

When engaging with smallholder farmers the socio-cultural, economic and environmental complexities

of these farming systems need to be taken into account; explored, understood and managed. Any new

ideas and processes need to be facilitated inclusive of all socio-cultural, economic and environmental

aspects and in a setting of open dialogue and learning.

2.1 LEARNING AND CHANGE

To engage in exploring the change in farming systems happening due to climate change and thinking

into the kinds of changes required to consciously adapt to these changes, requires both the process of

learning (including new ideas and information into the mix) and the process of doing (how to implement

and farm differently).

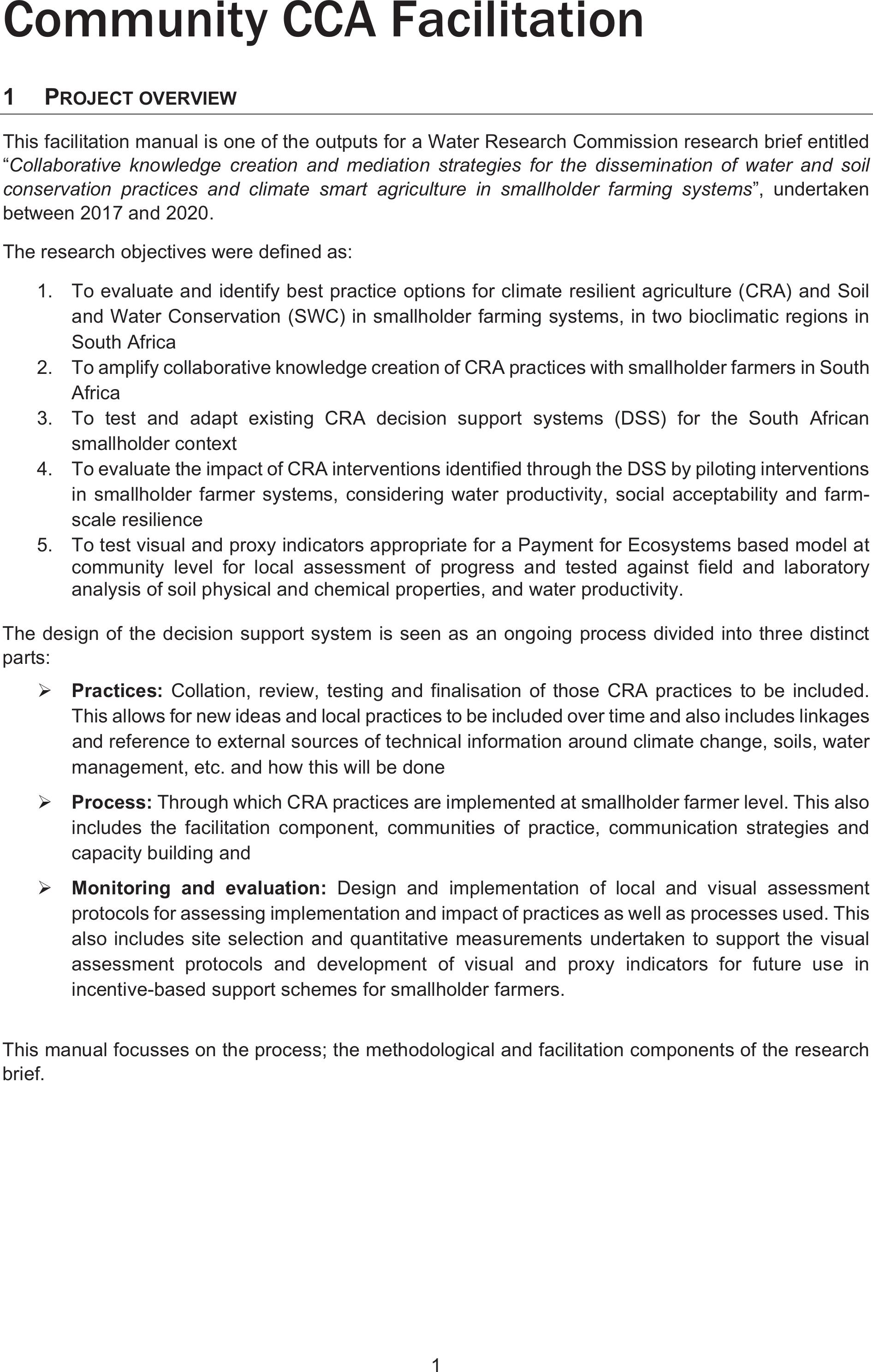

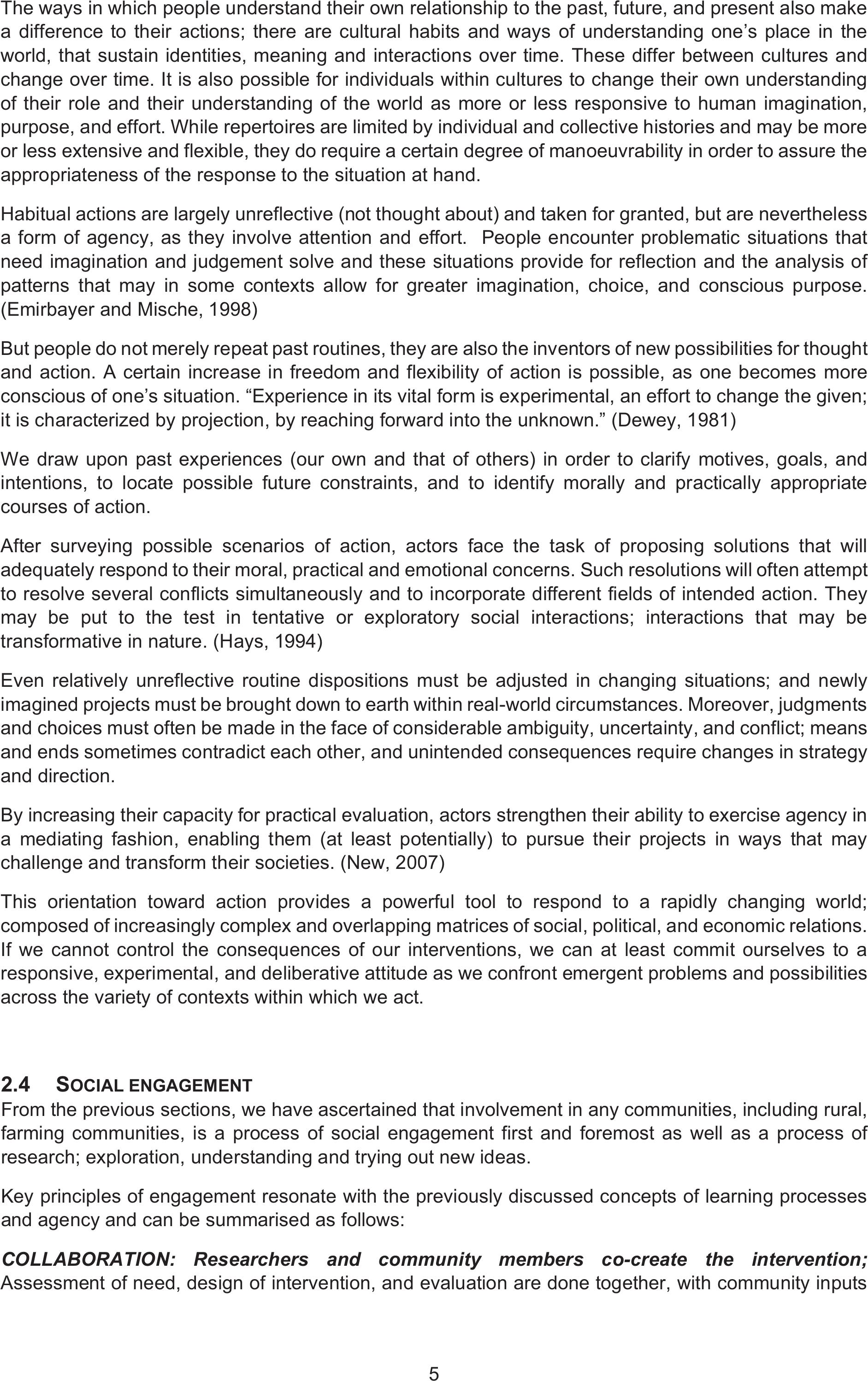

As adults, we learn best by doing. We retain the least information when we just listen to talks and

presentations or read. The diagram below provides a visual representation of how we best remember.

It also shows that combining learning and implementation and working in groups are generally the most

effective ways to learn.

Learning Pyramid (Adapted from National Training Laboratories Bethel, Maine, USA) (Dale E, 1969)

Figure 1: The learning pyramid demonstrating retention of information in different learning scenarios

It is widely appreciated that information on its own does not lead to capability development and that

education, training, knowledge dissemination and communication involving a range of knowledge

dissemination and mediation processes are required for information to translate into action (Lotz-Sisitka

and Pesanayi, 2019).

There are a number of different ways in which to understand learning and behaviour change in adult

learning processes. These processes have been defined within the ambit of educational psychology,

but are a useful tool in designing earning programmes for behaviour change.

3

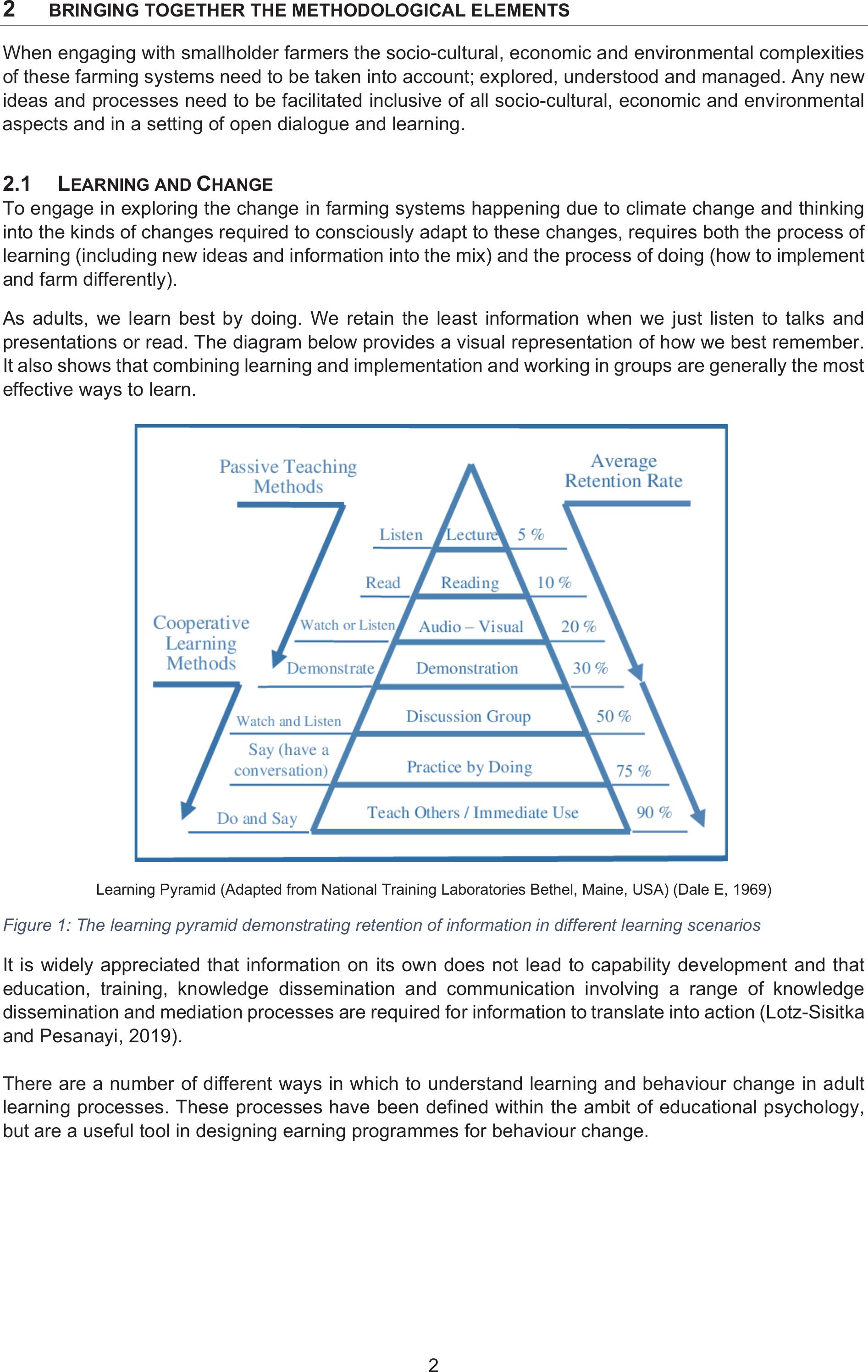

Over the years, academics have proposed a number of theories to describe and explain the learning

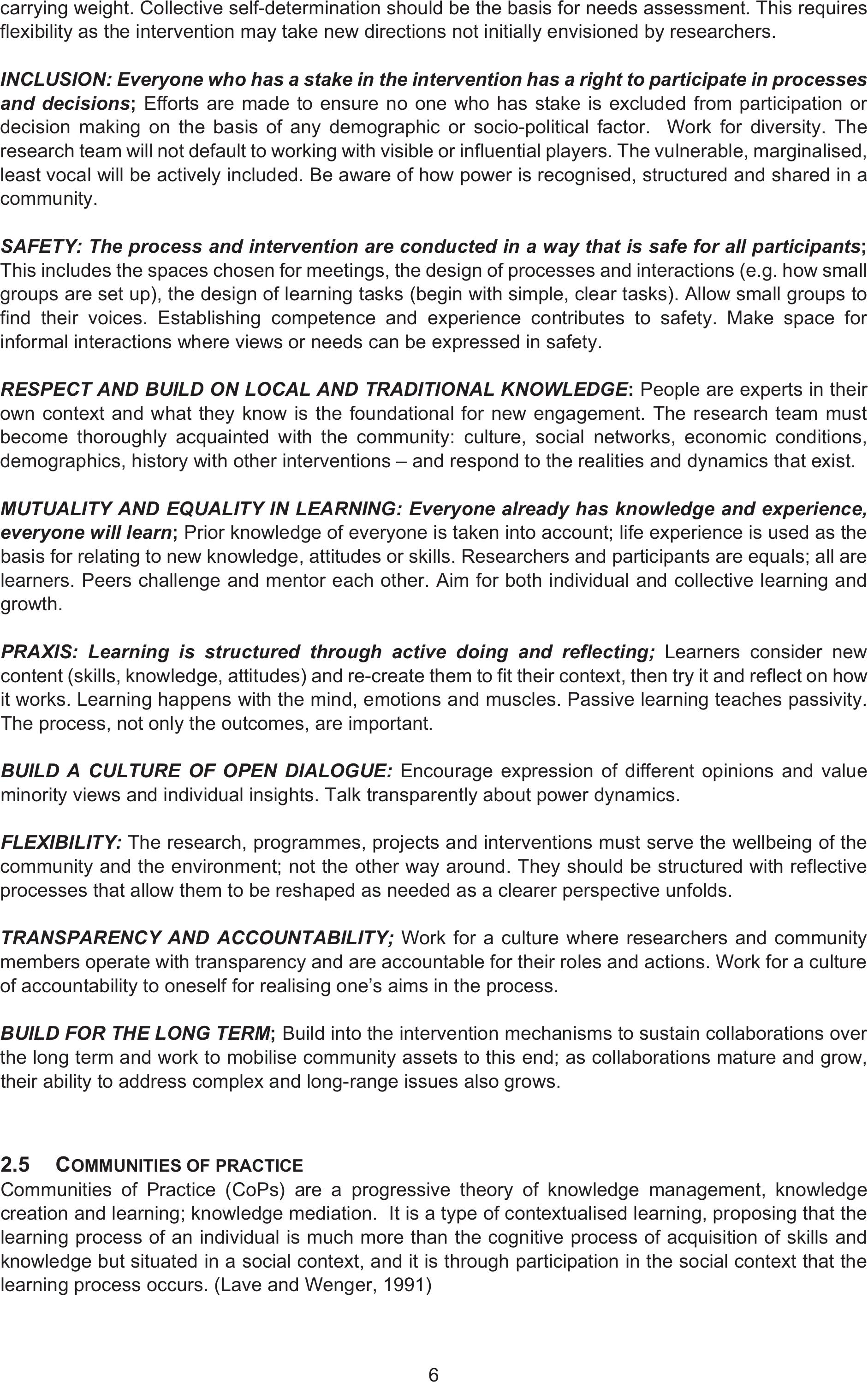

process – these can be grouped into five broad categories:

1. Behaviourist

2. Cognitivist

3. Constructivist

4. Experiential

5. Social and contextual

Figure 2: Five main learning theories

Behaviourism: Key behaviourist thinkers hypothesized that learning is a change in observable

behaviour caused by external stimuli in the environment (stimulus-response). The key principle of

behaviourism is the reward or punishment of a new behaviour, commonly described as the 'carrot and

stick' approach to learning.

Cognitivism: Cognitivism replaced behaviourism as the dominant learning paradigm in the 1960s and

proposes that learning comes from mental activity such as memory, motivation, thinking and reflection.

Cognitivism focuses on the transmission of information from someone who knows (such as an 'expert'

as opposed to facilitators) to learners who do not know.

Constructivism: From the constructivist perspective, learning is not a stimulus-response phenomenon

as described by behaviourism, rather it requires self-regulation and the building of conceptual structures

through reflection and abstraction. The learner takes an active role in constructing her own

understanding rather than receiving it from someone who knows, learning through observation,

processing and interpretation.

Experientialism: One of the key theorists of experiential learning is David Kolb who developed his

experiential model, as opposed to a purer cognitive model which formally recognised that people learn

from experience and described learning as following a cycle of experiential stages (observation, action

and reflection).

Social and Contextual: In this approach, learning does not occur solely within the learner, but in the

group (or context) and community in which they work. Learning is a shared process which takes place

through observing, working together and being part of a larger group, which includes colleagues of

varying levels of experience, able to stimulate each other's development. (Thompson, 2012)

Social learning is the most appropriate learning approach for working in complex community-based

situations.

2.2 SOCIAL LEARNING, KNOWLEDGE MEDIATION

Social Learning Theoryis a theory of the learning process which combines elements of behavioural,

cognitive and constructivist approaches. Learning is not purely behavioural, but is a cognitive process

that takes place in a social context.

Key tenets of Social Learning Theory (SLT) are as follows:

¾Learning can occur by observing a behaviourandby observing the consequences of the

behaviour

¾ Learning involves observation, extraction of information from those observations, and

making decisions about the performance of the behaviour (observational learning

or modelling). Thus, learning can occur without an observable change in behaviour.

¾Reinforcement plays a role in learning but is not entirely responsible for learning and

4

¾The learner is not a passive recipient of information. Cognition, environment, and behaviour

all mutually influence each other.

According to the sociocultural theory of education (an extension of SLT), learning is social; we learn

through interacting with others, through a meaningful exchange of ideas, concepts, and actions.

Knowledge is mediatedthrough dialoguing with the other (other members of the community,

stakeholders, facilitators, etc.). This process allows for the negotiation of meaning through dialogues

with others who have a different understanding of the topic. It allows for the interplay between different

sociocultural perspectives and the development of new understanding that can lead to different actions

and behaviours, or stated in a slightly different way”

“Contemporary theories of learning and change indicate that for knowledge or information to become

meaningful, there is 1) a need for the information to be related to the situation and experience of the

user; and that this needs to 2) be mediated in context; in addition to 3) providing new knowledge or

information that can expand existing knowledge and/or practice” (Lotz-Sisitka and Pesanayi, 2019).

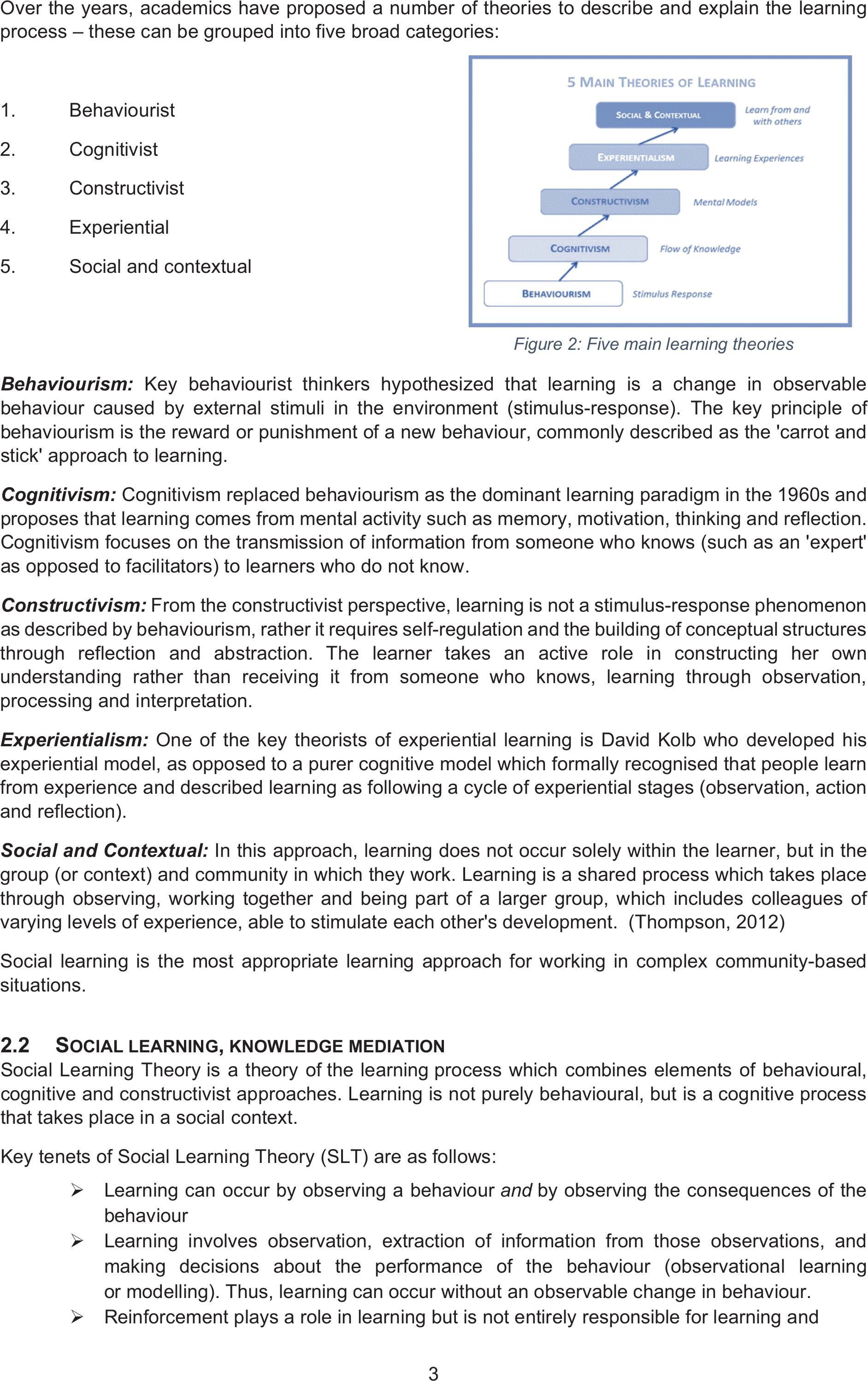

The model proposed by Shaxson et al. (2012), which proposes a ‘continuum’ of knowledge

dissemination approaches, contexts and relations within a systems approach to learning provides a

useful framework for project or programme design that incorporates social learning and change and

has recently been used in the Amanzi for Food social learning network approach (Lotz-Sisitka and

Pesanayi, 2019).

Figure 3: Knowledge dissemination continuum from Shaxson et al., 2012

Here, this framework will be used as a basis for building the methodological approach for innovation

system development and decision support for implementation of CRA in smallholder farming systems

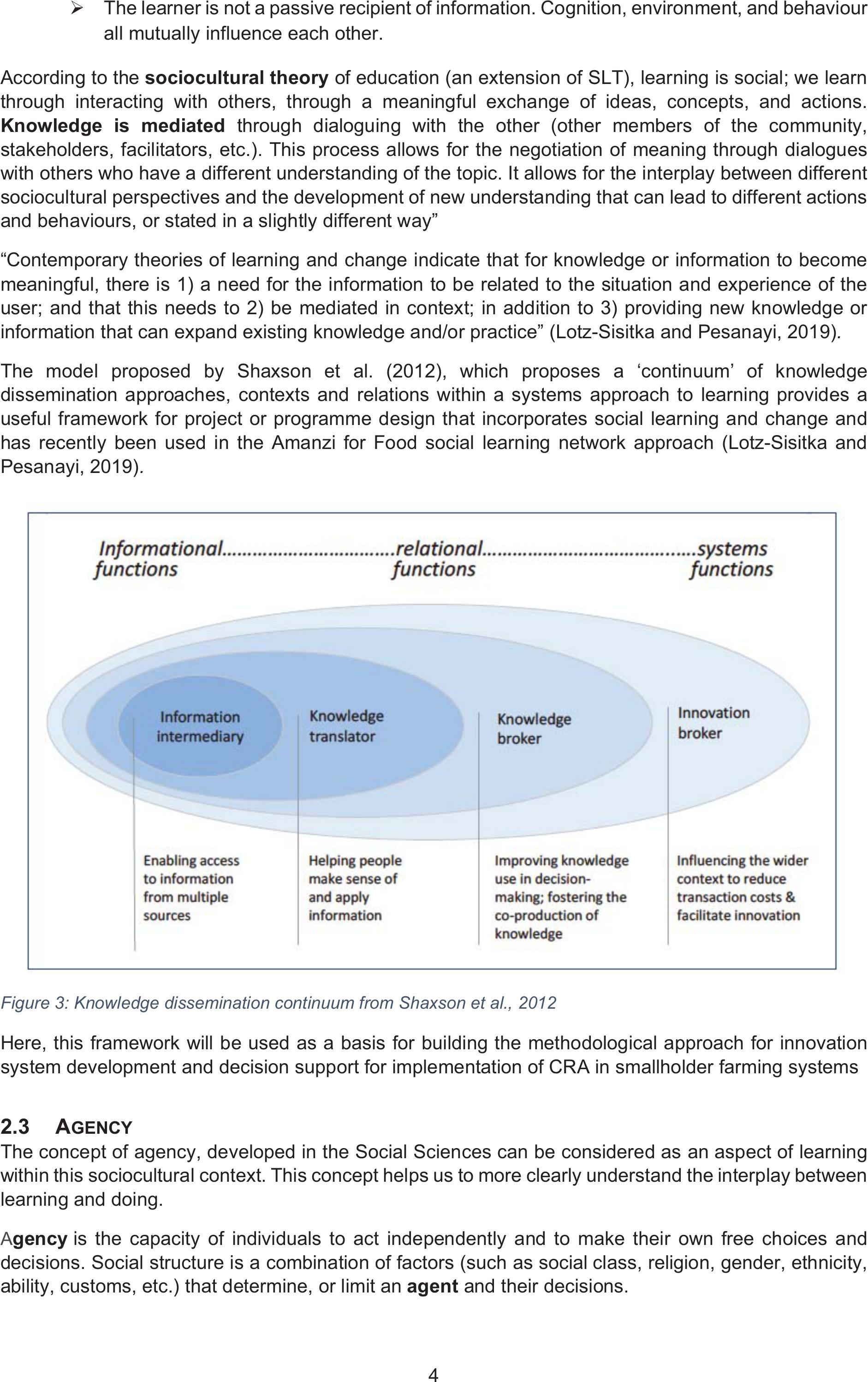

2.3 AGENCY

The concept of agency, developed in the Social Sciences can be considered as an aspect of learning

within this sociocultural context. This concept helps us to more clearly understand the interplay between

learning and doing.

Agencyis the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their own free choices and

decisions. Social structure is a combination of factors (such as social class, religion, gender, ethnicity,

ability, customs, etc.) that determine, or limit an agent and their decisions.

5

The ways in which people understand their own relationship to the past, future, and present also make

a difference to their actions; there are cultural habits and ways of understanding one’s place in the

world, that sustain identities, meaning and interactions over time. These differ between cultures and

change over time. It is also possible for individuals within cultures to change their own understanding

of their role and their understanding of the world as more or less responsive to human imagination,

purpose, and effort. While repertoires are limited by individual and collective histories and may be more

or less extensive and flexible, they do require a certain degree of manoeuvrability in order to assure the

appropriateness of the response to the situation at hand.

Habitual actions are largely unreflective (not thought about) and taken for granted, but are nevertheless

a form of agency, as they involve attention and effort. People encounter problematic situations that

need imagination and judgement solve and these situations provide for reflection and the analysis of

patterns that may in some contexts allow for greater imagination, choice, and conscious purpose.

(Emirbayer and Mische, 1998)

But people do not merely repeat past routines, they are also the inventors of new possibilities for thought

and action. A certain increase in freedom and flexibility of action is possible, as one becomes more

conscious of one’s situation. “Experience in its vital form is experimental, an effort to change the given;

it is characterized by projection, by reaching forward into the unknown.” (Dewey, 1981)

We draw upon past experiences (our own and that of others) in order to clarify motives, goals, and

intentions, to locate possible future constraints, and to identify morally and practically appropriate

courses of action.

After surveying possible scenarios of action, actors face the task of proposing solutions that will

adequately respond to their moral, practical and emotional concerns. Such resolutions will often attempt

to resolve several conflicts simultaneously and to incorporate different fields of intended action. They

may be put to the test in tentative or exploratory social interactions; interactions that may be

transformative in nature. (Hays, 1994)

Even relatively unreflective routine dispositions must be adjusted in changing situations; and newly

imagined projects must be brought down to earth within real-world circumstances. Moreover, judgments

and choices must often be made in the face of considerable ambiguity, uncertainty, and conflict; means

and ends sometimes contradict each other, and unintended consequences require changes in strategy

and direction.

By increasing their capacity for practical evaluation, actors strengthen their ability to exercise agency in

a mediating fashion, enabling them (at least potentially) to pursue their projects in ways that may

challenge and transform their societies. (New, 2007)

This orientation toward action provides a powerful tool to respond to a rapidly changing world;

composed of increasingly complex and overlapping matrices of social, political, and economic relations.

If we cannot control the consequences of our interventions, we can at least commit ourselves to a

responsive, experimental, and deliberative attitude as we confront emergent problems and possibilities

across the variety of contexts within which we act.

2.4 SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT

From the previous sections, we have ascertained that involvement in any communities, including rural,

farming communities, is a process of social engagement first and foremost as well as a process of

research; exploration, understanding and trying out new ideas.

Key principles of engagement resonate with the previously discussed concepts of learning processes

and agency and can be summarised as follows:

COLLABORATION: Researchers and community members co-create the intervention;

Assessment of need, design of intervention, and evaluation are done together, with community inputs

6

carrying weight. Collective self-determination should be the basis for needs assessment. This requires

flexibility as the intervention may take new directions not initially envisioned by researchers.

INCLUSION: Everyone who has a stake in the intervention has a right to participate in processes

and decisions; Efforts are made to ensure no one who has stake is excluded from participation or

decision making on the basis of any demographic or socio-political factor. Work for diversity. The

research team will not default to working with visible or influential players. The vulnerable, marginalised,

least vocal will be actively included. Be aware of how power is recognised, structured and shared in a

community.

SAFETY: The process and intervention are conducted in a way that is safe for all participants;

This includes the spaces chosen for meetings, the design of processes and interactions (e.g. how small

groups are set up), the design of learning tasks (begin with simple, clear tasks). Allow small groups to

find their voices. Establishing competence and experience contributes to safety. Make space for

informal interactions where views or needs can be expressed in safety.

RESPECT AND BUILD ON LOCAL AND TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE: People are experts in their

own context and what they know is the foundational for new engagement. The research team must

become thoroughly acquainted with the community: culture, social networks, economic conditions,

demographics, history with other interventions – and respond to the realities and dynamics that exist.

MUTUALITY AND EQUALITY IN LEARNING: Everyone already has knowledge and experience,

everyone will learn; Prior knowledge of everyone is taken into account; life experience is used as the

basis for relating to new knowledge, attitudes or skills. Researchers and participants are equals; all are

learners. Peers challenge and mentor each other. Aim for both individual and collective learning and

growth.

PRAXIS: Learning is structured through active doing and reflecting;Learners consider new

content (skills, knowledge, attitudes) and re-create them to fit their context, then try it and reflect on how

it works. Learning happens with the mind, emotions and muscles. Passive learning teaches passivity.

The process, not only the outcomes, are important.

BUILD A CULTURE OF OPEN DIALOGUE: Encourage expression of different opinions and value

minority views and individual insights. Talk transparently about power dynamics.

FLEXIBILITY:The research, programmes, projects and interventions must serve the wellbeing of the

community and the environment; not the other way around. They should be structured with reflective

processes that allow them to be reshaped as needed as a clearer perspective unfolds.

TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY;Work for a culture where researchers and community

members operate with transparency and are accountable for their roles and actions. Work for a culture

of accountability to oneself for realising one’s aims in the process.

BUILD FOR THE LONG TERM; Build into the intervention mechanisms to sustain collaborations over

the long term and work to mobilise community assets to this end; as collaborations mature and grow,

their ability to address complex and long-range issues also grows.

2.5 COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

Communities of Practice (CoPs) are a progressive theory of knowledge management, knowledge

creation and learning; knowledge mediation. It is a type of contextualised learning, proposing that the

learning process of an individual is much more than the cognitive process of acquisition of skills and

knowledge but situated in a social context, and it is through participation in the social context that the

learning process occurs. (Lave and Wenger, 1991)

7

It thus depends on a group of people, contextually defined, who share a common interest and a desire

to learn from and contribute to the community with their variety of experiences. Stated more simply, the

primary purpose of a CoP is to provide a way for practitioners to share tips and best practices, ask

questions of their colleagues, and provide support for each other.

Work on large, complex projects goes beyond the knowledge of one person to require the knowledge

and skills of people from different disciplines. They need to coordinate their activities and synthesize

their knowledge. Cross-disciplinary team participation requires an ability to negotiate team process and

participate in decision-making (Poggenpohl, 2015). It moves from primary experience through refined

reflection to explanation; moving from the tacit to the explicit.

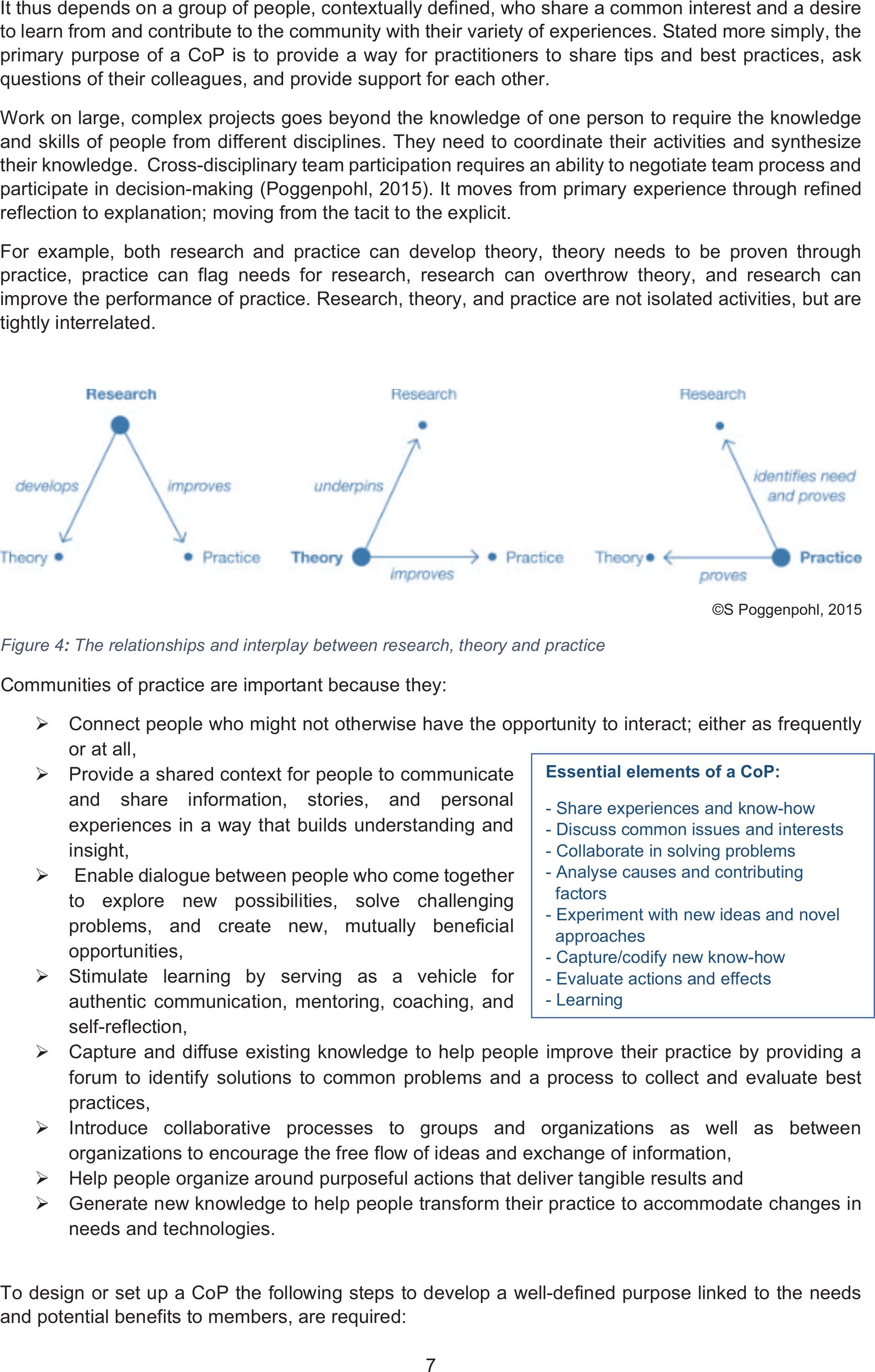

For example, both research and practice can develop theory, theory needs to be proven through

practice, practice can flag needs for research, research can overthrow theory, and research can

improve the performance of practice. Research, theory, and practice are not isolated activities, but are

tightly interrelated.

©S Poggenpohl, 2015

Figure 4: The relationships and interplay between research, theory and practice

Communities of practice are important because they:

¾Connect people who might not otherwise have the opportunity to interact; either as frequently

or at all,

¾Provide a shared context for people to communicate

and share information, stories, and personal

experiences in a way that builds understanding and

insight,

¾Enable dialogue between people who come together

to explore new possibilities, solve challenging

problems, and create new, mutually beneficial

opportunities,

¾Stimulate learning by serving as a vehicle for

authentic communication, mentoring, coaching, and

self-reflection,

¾Capture and diffuse existing knowledge to help people improve their practice by providing a

forum to identify solutions to common problems and a process to collect and evaluate best

practices,

¾Introduce collaborative processes to groups and organizations as well as between

organizations to encourage the free flow of ideas and exchange of information,

¾Help people organize around purposeful actions that deliver tangible results and

¾Generate new knowledge to help people transform their practice to accommodate changes in

needs and technologies.

To design or set up a CoP the following steps to develop a well-defined purpose linked to the needs

and potential benefits to members, are required:

Essential elements of a CoP:

- Share experiences and know-how

- Discuss common issues and interests

- Collaborate in solving problems

- Analyse causes and contributing

factors

- Experiment with new ideas and novel

approaches

- Capture/codify new know-how

- Evaluate actions and effects

- Learning

8

1. Developing relationships: Interaction with and developing of a wider network of peers working

with a process of building trust, reciprocity, mutual respect and commitment.

2. Developing practice: Practice evolves with the community as a collective product, becomes

integrated into members’ work and organizes knowledge in a way that reflects practitioners’

perspectives. Successful practice development depends on a balance between “the production

of ‘things’ like documents or tools and deep learning experiences for community members.

3. Carrying out tasks and projects:Small group projects, sponsored by the community, help

members create personal relationships and also provide a way to produce the resources for

developing the practice: cases, effective practices, tools, methods, articles, lessons learned,

databases, learning tools and aids, models and the like.

4. Creating new knowledge:Members go beyond current practice to explore the cutting edge of

the domain, to innovate. Community may redefine its boundaries and membership and foster

boundary-crossing, possibly working with people from other communities to explore emerging

technologies, practices, and ideas.

Actions for the CoP are based on the premises of inquiry, design, activities, communication, interaction,

learning, knowledge sharing, collaboration, roles and social structures and piloting and roll out of the

processes.

Examples of CoPs are learning groups, innovation platforms, forums, networks and research and

implementation teams.

2.6 INNOVATION SYSTEMS

Methodologies for agricultural development and research have been designed to incorporate the

concepts of social engagement, learning, experimentation and agency into the process.

The international development community is giving increased attention to agricultural innovation

processes and systems that lead to outcomes at scale. Inclusive multi-dimensional and multi-

stakeholder learning processes are seen as important. Smallholder family farmers become more

central in the design and implementation of research processes as partners in planning and

implementation processes (Kruger and Gilles, 2014).

Key trends in Participatory Agricultural development thinking show a movement or change from:

¾Increases in production to improvement in local livelihoods,

¾Technology transfer to local innovation development,

¾Beneficiaries of projects to influential stakeholders within programmes,

¾Technology transfer to co-development of innovation systems,

¾Functional participation to empowerment and

¾Applied and adaptive research to strategic and pre-adaptive research.

Global experience shows that new ways of thinking about and doing agricultural research and

development are required. The basic paradigm shift is one of moving away from the idea that research

and development is a process of generating and transferring modern technology to farmers. And then

moving towards seeing the idea as an inclusive multi-dimensional learning process that:

¾Works from a holistic perspective that includes biophysical, socio-political and economic

perspectives in agriculture and natural resource management,

¾Draws upon diverse sources of knowledge – from local to global,

¾Provides for meaningful participation of user groups in the process of investigating improvements

in local situations,

9

¾And builds synergy between local capacities, resources and innovations by

oProviding decision support tools and information that enables various types of users to

make strategic choices and actions,

¾Which results in a wide range of knowledge products (technological through to socio-political) for

generating, sharing, exchanging and utilizing knowledge.

Now, concepts such as strategic and pre-adaptive participatory research become important as does

the idea of best practise scenarios and options and the mainstreaming of cross cutting issues and

themes. In many ways, these concepts are still in a developmental phase and are not as yet integral in

existing institutional and research cultures.

The development of methodological frameworks and processes to encompass the above themes and

goals has followed two broad tracks/lines depending to an extent, on the type of institution at work and

their overall aims; namely Participatory Action research (PAR) and Participatory Innovation

Development (PID). (Brock and Pettit, 2007).

2.7 PARTICIPATORY INNOVATION DEVELOPMENT (PID)

Participatory Innovation Development (PID) is an approach to learning and innovation that is used

in international development as part of projects and programmes relating to sustainable agriculture. The

approach involves collaboration between researchers and farmers in the analysis of agricultural

problems and testing of alternative farming practices.

It has developed out of methodologies such as Farming Systems Research and Extension, PRA

(participatory rural appraisal), PLA (participatory learning and action) and Indigenous Technical

Knowledge Systems and incorporates further methodologies such as Farmer Field Schools.

This approach enables the research and development community to respond to locally defined

problems and to find solutions that build upon local knowledge and are consistent with local resources

and contexts. Moreover, by involving farmers as the users of the research process, it is more likely that

farmers would share and use (new) knowledge.

Local innovation in agriculture and natural resource management goes beyond technologies to socio-

organizational arrangements such as new ways of regulating the use of resources, new ways of

community organization, or new ways of stakeholder interaction. The term Participatory Innovation

Development (PID) embraces this broader understanding of joint research and development and is now

being used alongside, or in place of PTD (Participatory Technology Development). It is a process in

which farmers and other stakeholders engage in joint exploration and experimentation leading to new

technologies or socio-institutional arrangements for more sustainable livelihoods. This action-oriented

approach promotes engagement in a process that strengthens the capacities of agricultural services to

support community-led initiatives (Hartmann, 2009, Wettasinha et al., 2009).

The following statement in a recent publication in the agricultural development and extension field, sums

up the imperative for working with these approaches:

10

“Scientists are being challenged to re-consider that their role in technology development is through

innovation and a complex process involving a reorganization of social relationships, not just technical

practice. In this context, technology shifts from something to be applied to something leveraged for

networking and organizing. To ensure the future, the idea of sustainability as a dynamic process rather

than an endpoint offers a route for understanding and engagement between research, policy and

personal spheres. For both research and extension agendas; in considering traditional agriculture in

the context of economic development we have to create the capacity to co-operate in a way that opens

up the possibility of social change; a way of interacting that preserves and creates new forms of social

cohesion. Researchers will come to understand that attitude, environment and relevant issues, not

specific tools, achieves participation” (Caister et al., 2012).

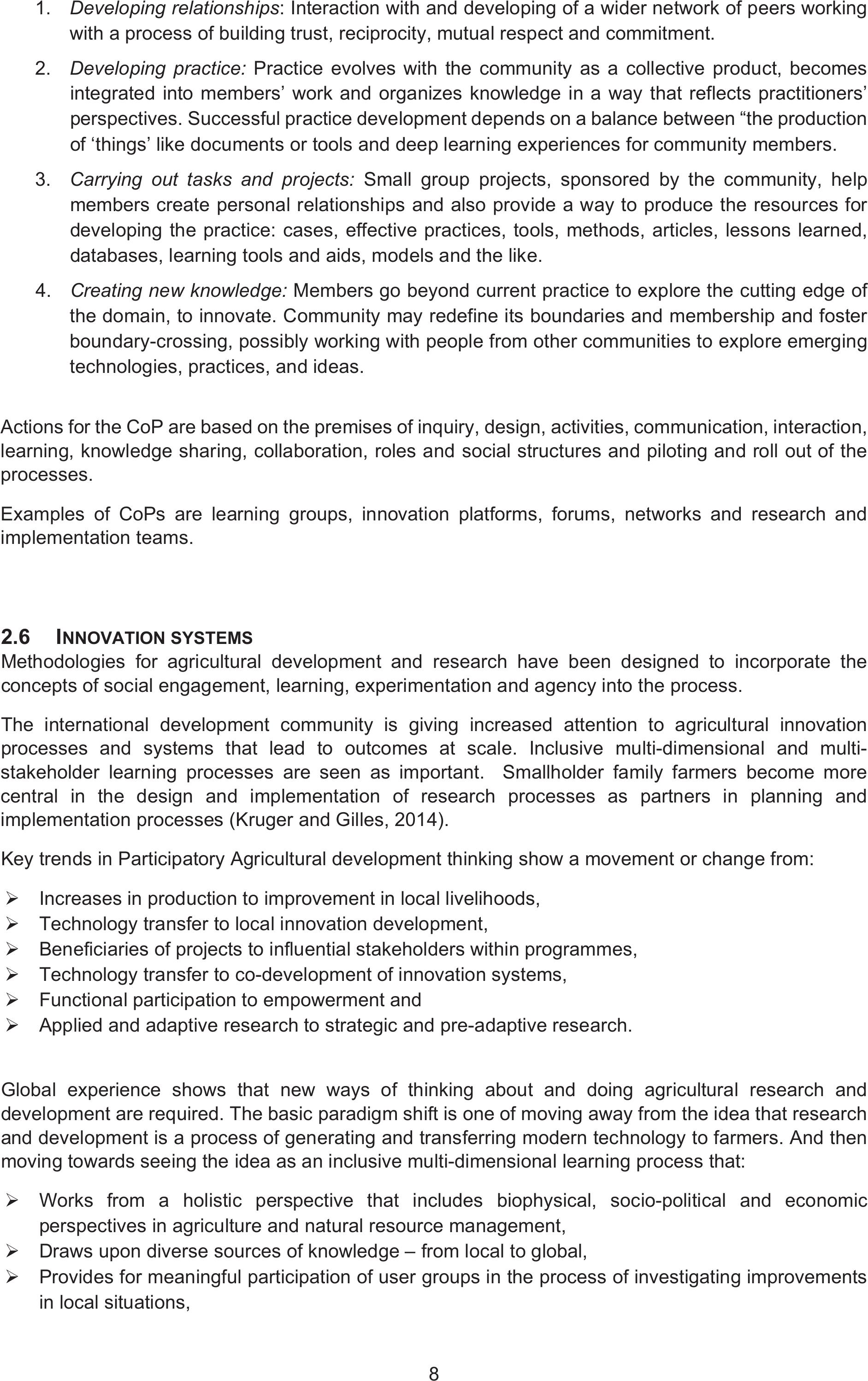

Figure 5: The interplay between researchers, facilitators and farmers, indicating associated methodologies

Farmer led innovation builds on the PID concepts to include local innovations into the system and

describes the interaction between local communities and outside facilitators, as:

¾Gaining a joint understanding of the main

characteristics and changes of that particular

agroecological system,

¾Defining priority problems,

¾ Experimenting locally with a variety of options

derived both from indigenous knowledge … and

from formal science and

¾Enhancing farmer’s experimental capacities and

farmer-to-farmer communication (Wettasinha et

al., 2009, Rai and Shrestha, 2006).

The text box alongside provides an example of steps

that can be followed to implement a farmer led

innovation process.

A summary of the Farmer Led Innovation

steps

1.Getting started (getting to know each

other);

2.Joint analysis of the situation – the

problems and opportunities;

3.Looking for things to try to improve the local

situation;

4.Trying them out in community-led

participatory experimentation;

5.Jointly analysis and sharing the results; and

6.Strengthening the process, often through

improving local organization and linkages

with other actors in R&D, so that the

innovation process will continue.

PRA/PLA

Farmer to Farmer

PTD/ PID

PAR (Participatory action research)

PRA/PLA (Participatory rural

appraisal/participatory learning and

action)

Farming systems research

Farmer participatory research

PTD/PID (participatory

technology/innovation development)

FFS (Farmer field schools)

PID

Agroecology

Researcher

Developmentfacilitator/

extension/ innovator

Farmer

11

2.8 ADDING THE ELEMENTS TOGETHER: COACTIVE GOVERNANCE IN A CHANGING CLIMATE

The concept of coactive governance is borrowed from industry, where it is being developed to manage

service relationships. This new way shares strategy and responsibility between the client and provider

equally and allows an innovation environment to flourish. Implementing collaborative models in

enterprise environments requires organizational readiness – that is, willingness – to adopt a different

working attitude that accepts change as a condition, rather than an event (Batty, 2017).

In this process we need to combine and synergise the way people learn, what they learn and how they

incorporate this learning into changing their practice into a coherent model that can support an individual

farmer’s decision-making process about which adaptive practices to implement in their context and

farming system.

12

3 CLIMATE CHANGE

There is ample evidence of national and local changes in the temperature and rainfall climatology of

South Africa over at least the past five decades and a high probability that these changes will increase

in the coming decades:

xMean annual temperatures have increased by more than 1.5 times the observed global average of

0.65°C,

xMaximum and minimum temperatures have been increasing annually and in almost all seasons,

xHot and cold extremes have increased and decreased respectively in frequency, in most seasons

across the country, particularly in the western and northern interior,

xIn almost all hydrological zones there has been a marginal reduction in rainfall for the autumn

months. Annual rainfall has not changed significantly, but an overall reduction in the number of rain

days implies a tendency towards an increase in the intensity of rainfall events and increased dry

spell duration and

xExtreme rainfall events show a tendency towards increasing in frequency annually, and especially

in spring and summer, with a reduction in extremes in autumn (DEA, 2013).

Given South Africa’s present trajectory and already alarming increase in average temperatures, the

predictions of strongly increased drought, increased rainfall variability and strongly increased extreme

rainfall events into the future are all but guaranteed.

Climate change impacts on South Africa are likely to be felt primarily via effects on water resources;

with increased evapotranspiration, run-off and soil erosion and reduced surface and underground water

reserves. Significant trade-offs are likely to occur between developmental aspirations, particularly in

terms of the allocation between agricultural and urban-industrial water use, linked to the high costs of

enhancing water supply (DEA, 2017).

With regard to the impact of climate change on food security in Southern Africa, the IPPC makes the

following predictions:

xMaize-based systems, particularly in Southern Africa, are among the most vulnerable to climate

change with predicted yield losses for South Africa and Zimbabwe in excess of 30%,

xLoss of livestock under prolonged drought conditions is a critical risk given the extensive rangeland

in Southern Africa that is prone to drought,

xGroundwater recharge may also be significantly affected by climate change in areas that receive

less than 500 mm per year.

3.1 CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION

Small-holder farmers and pastoralists in particular are being especially hard hit by these changes. Many

of these small-scale producers are already coping with a degraded natural resource base. They often

lack knowledge about potential options for adapting their production systems and have limited assets

and risk-taking capacity to access and use technologies and financial services (SARVA, 2013).

Climate change is intricately linked to almost all facets of our society, particularly socio-economic

progression as resources such as water, feedstock in the form of food and fibre and biodiversity,

amongst others determine the production potential of many sectors of the economy, which in turn affect

human development aspirations of the country.

In South Africa, emphasis is being placed on the development of policies and strategies for climate

change mitigation, albeit slowly, with a much smaller focus on adaptation. Nonetheless, processes such

as collaborative, participatory research that includes scientists and farmers, strengthening of

communication systems for anticipating and responding to climate risks, and increased flexibility in

livelihood options, which serve to strengthen coping strategies in agriculture for near-term risks from

13

climate variability, provide potential pathways for strengthening adaptive capacities for climate change

(IPCC, 2014).

The IPCC defines adaptation as the “adjustments in human and natural systems in response to actual

or expected climatic stimuli or effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities” (ibid.).

Planned adaptations to climate risks are “most likely to be implemented when they are developed as

FRPSRQHQWVRIRUDVPRGL¿FDWLRQVWRH[LVWLQJUHVRXUFHPDQDJHPHQWSURJUDPVRUDVSDUWRIQDWLRQDO

or regional strategies for sustainable development.” (ibid.).

3.2 CLIMATE SMART / RESILIENT AGRICULTURE

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) presented its response to climate change;

an approach it has termed Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) in 2010 (FAO, 2013). In this study, the

research team opted to use the term Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRA), to clearly situate the practices

promoted here within the agroecological sphere, rather than the technological and internet of things

spheres, which are also considered climate smart under the broader definition.

According to the FAO, “Enhancing food security while contributing to mitigation of climate change and

preserving the natural resource base and vital ecosystem services requires the transition to agricultural

production systems that are more productive, use inputs more efficiently, have less variability and

greater stability in their outputs, and are more resilient to risks, shocks and long-term climate variability.

More productive and more resilient agriculture requires a major shift in the way land, water, soil nutrients

and genetic resources are managed to ensure that these resources are used more efficiently” (ibid.)

CRA contributes to the achievement of sustainable development goals. It integrates the three

dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental) by jointly addressing

food security and climate challenges. It is composed of three main pillars:

1. Sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and incomes,

2. Adapting and building resilience to climate change and

3. Reducing and/or removing greenhouse gases emissions, where possible.

This approach aims to strengthen livelihoods and food security, by improving the management and use

of natural resources and adopting appropriate methods and technologies for the production, processing

and marketing of agricultural goods. The approach is entirely compatible with the idea that CRA

practices are essentially good developmental agricultural practices, applicable in and suitable for a wide

range of contexts (ibid).

Climate Smart Agriculture is the overarching approach (shown in the diagram below) that has been

used to inform this decision support process for smallholder farmers. All CSA practices have the

potential to directly benefit farmers and increase food production in the communities as a whole,

irrespective of any climate change predictions. However, they also have the capacity to buffer farmers

against any increases in temperature or changes in rainfall quantities and patterns occasioned by

climate change.

14

Figure 6: The FAO concept of CSA as an overarching approach to sustainable development (Arslan, 2014)

The FAO characterises CSA as an approach that:

1. Addresses the complex interrelated challenges of food security, development and climate

change and identifies integrated options that create synergies and benefits and reduce trade-

offs

2. Recognizes that these options will be shaped by specific country contexts and capacities and

by the particular social, economic and environmental situation where it will be applied

3. Assesses the interactions between sectors and the needs of different involved stakeholders

4. Identifies barriers to adoption, especially among farmers and provides appropriate solutions in

terms of policies, strategies, actions and incentives,

5. Seeks to create enabling environments through a greater alignment of policies, financial

investments and institutional arrangements

6. Strives to achieve multiple objectives with the understanding that priorities need to be set and

collective decisions made on different benefits and trade-offs

7. Prioritizes the strengthening of livelihoods, especially those of smallholders, by improving

access to services, knowledge, resources (including genetic resources), financial products and

markets

8. Addresses adaptation and builds resilience to shocks, especially those related to climate

change, as the magnitude of the impacts of climate change has major implications for

agricultural and rural development

9. Considers climate change mitigation as a potential secondary co-benefit, especially in low-

income, agricultural-based populations and

10. Seeks to identify opportunities to access climate-related financing and integrate it with

traditional sources of agricultural investment finance (FAO, 2013).

The FAO’s description of CSA makes it clear that appropriate technologies that have been developed

under different agricultural regimes can be entirely compatible with the broad concept of CRA. The

approach here is to work directly with smallholders in local contexts to improve practices and synergise

across sectors. The emphasis is thus at farm/household level. Here CRA aims to improve aspects of

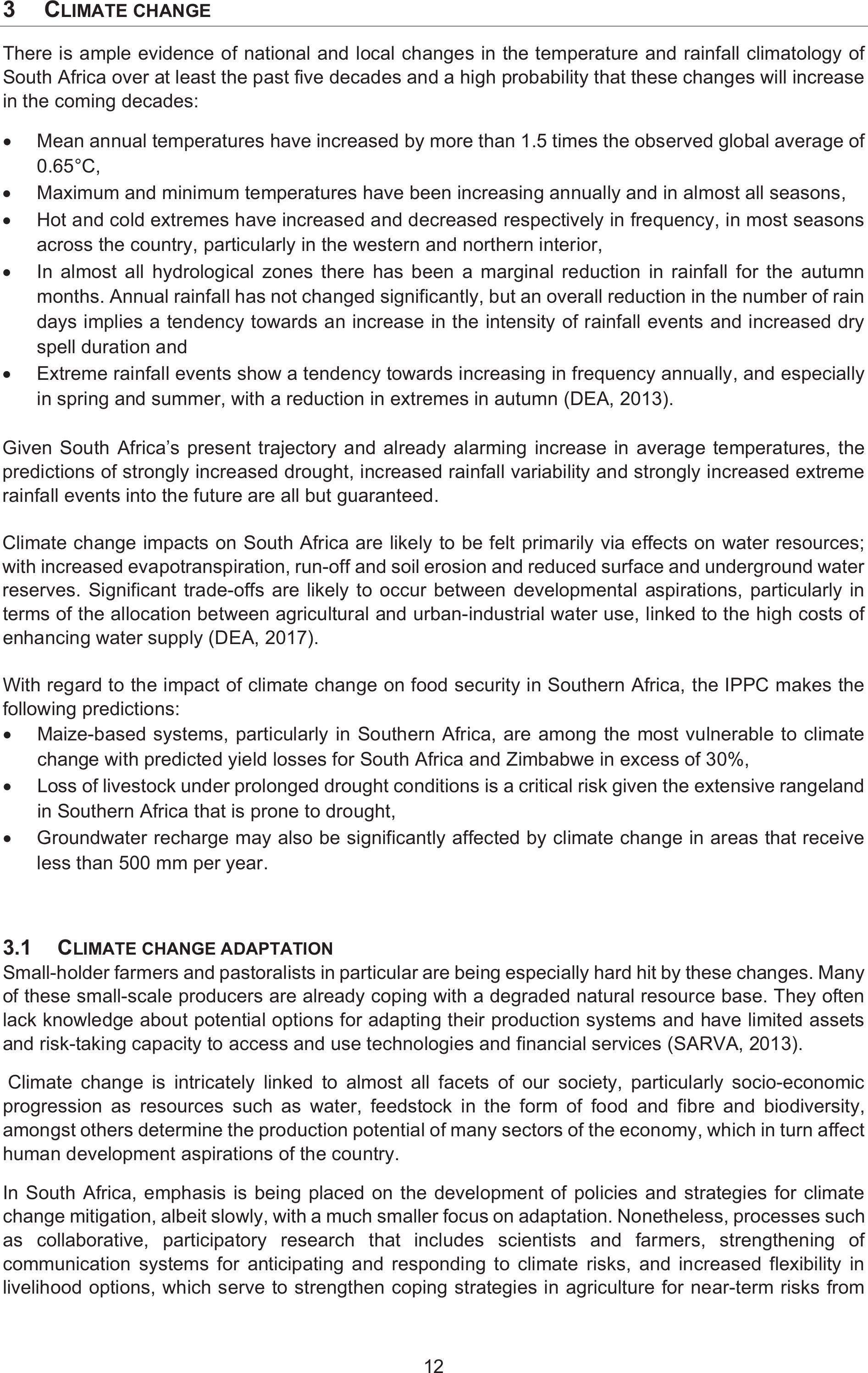

crop production, livestock and pasture management, natural resource management, as well as soil and

water management as depicted in Figure 7.

From farm-basedto comprehensivedevelopmentconcepts

Conservation agriculture

Sustainable land

management

Agroecology

Organic farming

Macro

Micro

Farming

technics

Area - based

management

Multi-function

planning and policies

Climatesmart agriculture

Value

chain

15

Figure 7: Household level implementation of CRA integrates across sectors (adapted from Arslan, 2014)

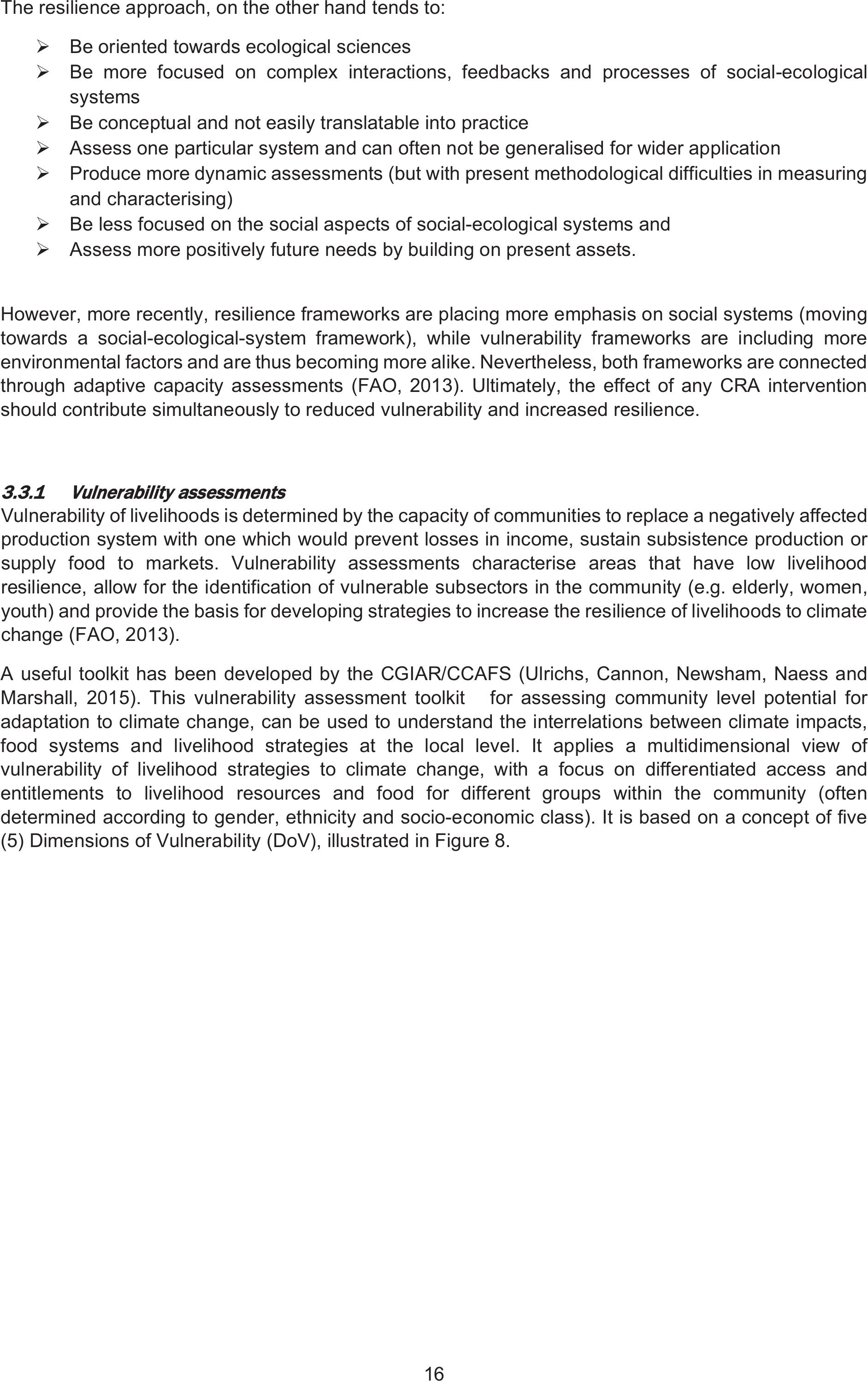

3.3 CONCEPTS OF VULNERABILITY AND RESILIENCE

Vulnerability is a function of two factors:

¾Firstly, impact (exposure and sensitivity of exposure to climate change in turn)

oExposure – refers to the extent to which a system is impacted by climate change

oSensitivity – refers to how affected the system is after the exposure

¾ Secondly, adaptive capacity – the ability of the system to avoid potential damages, take

advantage of opportunities and cope with the consequences of damages. It can also be framed

as the capacity of people in a given system to influence resilience

Resilience is the ability of a system to anticipate, absorb, accommodate or recover from the effects of

an extreme climate event in a timely and efficient manner.

Contextual vulnerability is locally focussed and considers the present as the departure point and

considers socio-economic dimensions of vulnerability as a basis for assessing future vulnerability. This

is largely a participatory process as opposed to modelling approaches that are applied at programme

and policy scales. Vulnerability and adaptation needs are contextualised with the local context and will

include factors that aren’t necessarily directly linked to climate change or CRA.

Vulnerability and resilience frameworks are different in key aspects (FAO, 2013).

The vulnerability approach tends to:

¾Be oriented towards research on hazards and risks

¾Be centred on people and more translatable to application and policy outcomes

¾Conduct assessments for single spatial scale and ‘snapshots’ in time

¾Be less focused on ecological and environmental aspects and

¾Assess present and future vulnerability from past information.

SYNERGIES

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

SY

S

S

S

SY

Y

SY

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

Y

Y

Y

NE

NE

NE

NE

NE

NE

N

NE

N

NE

NE

E

NE

E

NE

N

N

NE

N

N

E

RGRG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

RG

G

G

G

RG

RG

G

G

RG

G

R

R

G

G

G

G

R

R

R

G

IE

IE

IE

IE

IE

IE

IE

E

E

IE

IE

IE

E

IE

E

I

E

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

Soil

and water

conservation

16

The resilience approach, on the other hand tends to:

¾Be oriented towards ecological sciences

¾Be more focused on complex interactions, feedbacks and processes of social-ecological

systems

¾Be conceptual and not easily translatable into practice

¾Assess one particular system and can often not be generalised for wider application

¾Produce more dynamic assessments (but with present methodological difficulties in measuring

and characterising)

¾Be less focused on the social aspects of social-ecological systems and

¾Assess more positively future needs by building on present assets.

However, more recently, resilience frameworks are placing more emphasis on social systems (moving

towards a social-ecological-system framework), while vulnerability frameworks are including more

environmental factors and are thus becoming more alike. Nevertheless, both frameworks are connected

through adaptive capacity assessments (FAO, 2013). Ultimately, the effect of any CRA intervention

should contribute simultaneously to reduced vulnerability and increased resilience.

3

3.3.1

Vulnerability assessments

Vulnerability of livelihoods is determined by the capacity of communities to replace a negatively affected

production system with one which would prevent losses in income, sustain subsistence production or

supply food to markets. Vulnerability assessments characterise areas that have low livelihood

resilience, allow for the identification of vulnerable subsectors in the community (e.g. elderly, women,

youth) and provide the basis for developing strategies to increase the resilience of livelihoods to climate

change (FAO, 2013).

A useful toolkit has been developed by the CGIAR/CCAFS (Ulrichs, Cannon, Newsham, Naess and

Marshall, 2015). This vulnerability assessment toolkit for assessing community level potential for

adaptation to climate change, can be used to understand the interrelations between climate impacts,

food systems and livelihood strategies at the local level. It applies a multidimensional view of

vulnerability of livelihood strategies to climate change, with a focus on differentiated access and

entitlements to livelihood resources and food for different groups within the community (often

determined according to gender, ethnicity and socio-economic class). It is based on a concept of five

(5) Dimensions of Vulnerability (DoV), illustrated in Figure 8.

17

Figure 8: The 5 dimensions of vulnerability (CGIAR/CCAFS, 2015)

For each of these vulnerability dimensions a set of criteria and indicators can be developed to

benchmark the baseline conditions in a locality. A wide range of participatory approaches, techniques

and practices are available and include for example: transect walks, village mapping, historical timelines

and climate trends, well-being ranking, seasonal calendars, ranking of livelihood strategies, chaining

farming practices and crops, climate risk and coping mechanisms matrix, food system analysis and

institutional mapping and Venn diagrams

3.4 SMALLHOLDER FARMING IN SOUTH AFRICA AND CRA

Development in South Africa is inextricably tied to massive challenges rooted in both the past and in

the future. In the past, colonial appropriation and control of access to resources was taken to disastrous

extremes through the policies of apartheid; twenty-five years into democracy poverty and dispossession

still plague us. At the same time, problems anticipated in the future already loom large: South Africa as

a water stressed country can expect to face particularly difficult challenges in terms of food security due

to the increased temperatures and pests and decreased water access anticipated to result from climate

change

About 2.5 million households (15,6%) were involved in agricultural activities in South Africa in 2017.

Most of these households are found in Limpopo (25%), Eastern Cape (20%) and KwaZulu-Natal (20%).

They are mainly headed by females (52,8%) and mostly involved in the production of fruits and

vegetables (53,4%), grain and other food crops (51,8%), as well as in livestock (47,1%) and poultry

(35,3%) farming. The main source of income for these households is social grants. Furthermore, most

households involved in agricultural activities do so to supplement food for the household (43,7%)

(StatsSA, 2017).

Poverty levels in the rural areas of South Africa are difficult to assess and are now believed to be a lot

higher than the officially recorded level. Indigency, as recorded by the municipalities is around 22% of

households, meaning that these households earn less than R3200/ month (7 household members). In

2015, over half of South Africa’s population (55.5%) lived in poverty, below the poverty line – for which

the upper bound poverty line was R1 183 per person in 2018. This percentage is slowly increasing

every year. Poverty is highest in the provinces with the largest rural populations; the Eastern Cape,

Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal (Africheck, 2018). Women headed households are more vulnerable to

poverty.

18

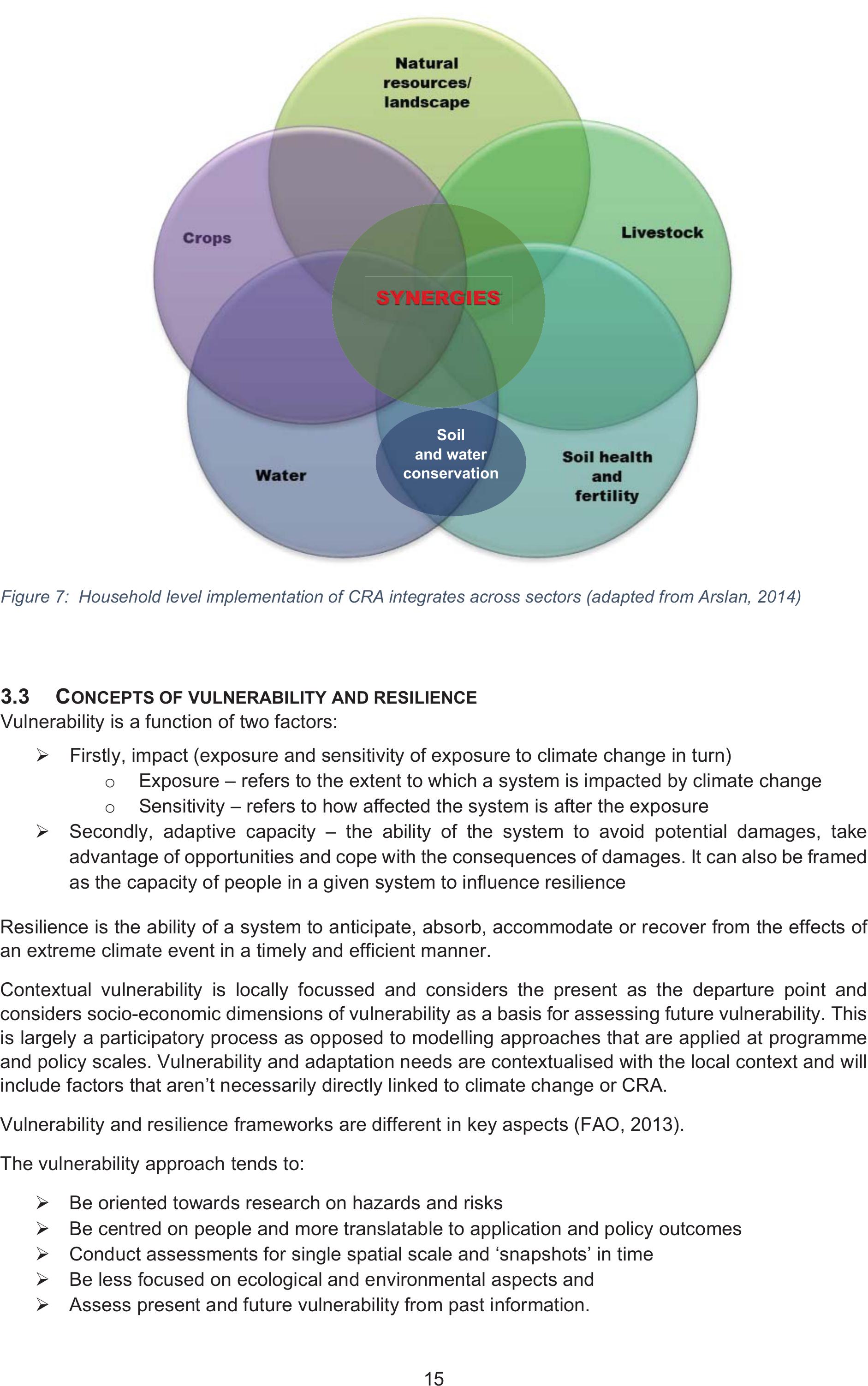

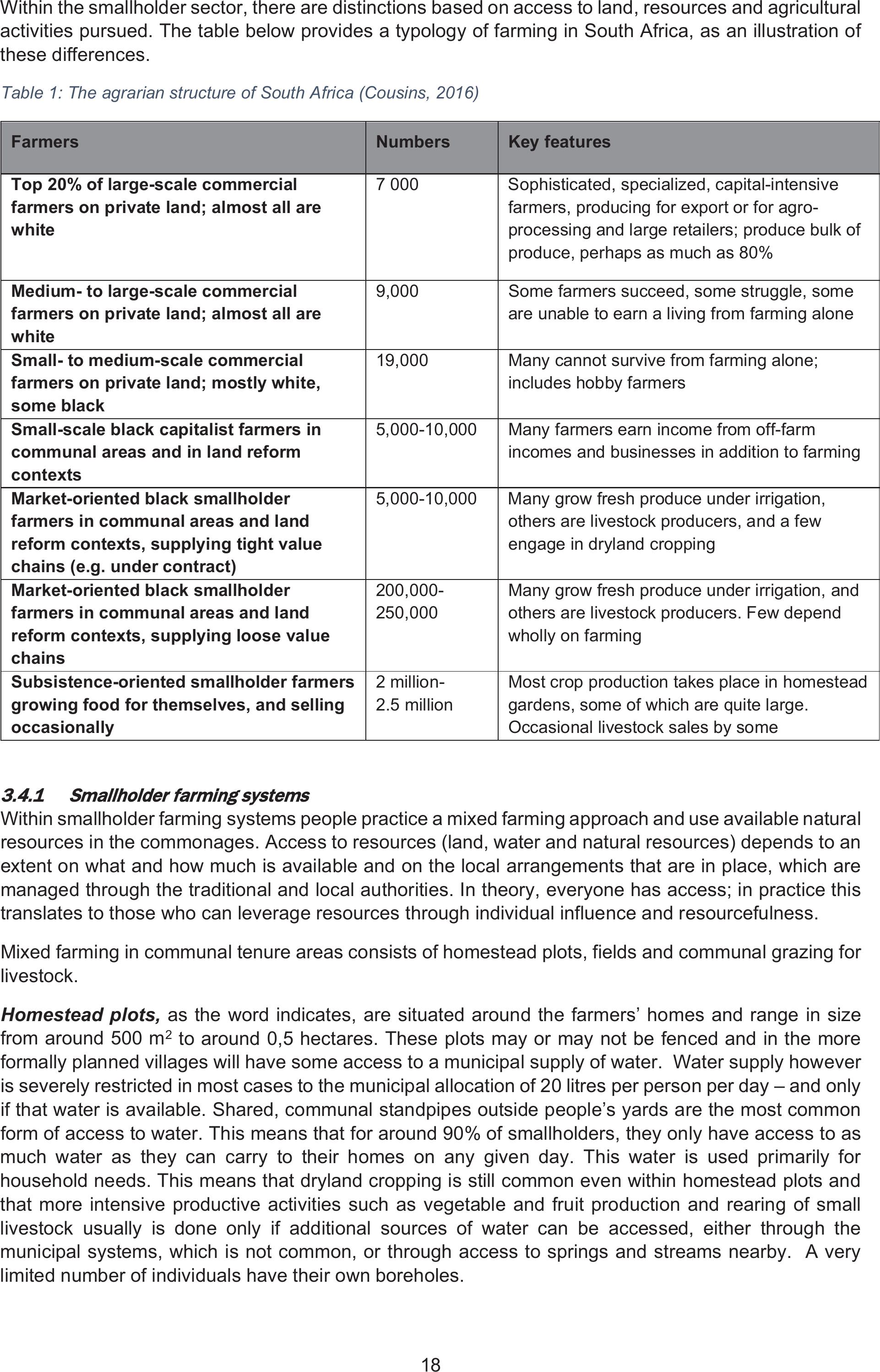

Within the smallholder sector, there are distinctions based on access to land, resources and agricultural

activities pursued. The table below provides a typology of farming in South Africa, as an illustration of

these differences.

Table 1: The agrarian structure of South Africa (Cousins, 2016)

Farmers Numbers Key features

Top 20% of large-scale commercial

farmers on private land; almost all are

white

7 000 Sophisticated, specialized, capital-intensive

farmers, producing for export or for agro-

processing and large retailers; produce bulk of

produce, perhaps as much as 80%

Medium- to large-scale commercial

farmers on private land; almost all are

white

9,000 Some farmers succeed, some struggle, some

are unable to earn a living from farming alone

Small- to medium-scale commercial

farmers on private land; mostly white,

some black

19,000 Many cannot survive from farming alone;

includes hobby farmers

Small-scale black capitalist farmers in

communal areas and in land reform

contexts

5,000-10,000 Many farmers earn income from off-farm

incomes and businesses in addition to farming

Market-oriented black smallholder

farmers in communal areas and land

reform contexts, supplying tight value

chains (e.g. under contract)

5,000-10,000 Many grow fresh produce under irrigation,

others are livestock producers, and a few

engage in dryland cropping

Market-oriented black smallholder

farmers in communal areas and land

reform contexts, supplying loose value

chains

200,000-

250,000

Many grow fresh produce under irrigation, and

others are livestock producers. Few depend

wholly on farming

Subsistence-oriented smallholder farmers

growing food for themselves, and selling

occasionally

2 million-

2.5 million

Most crop production takes place in homestead

gardens, some of which are quite large.

Occasional livestock sales by some

3

3.4.1

Smallholder farming systems

Within smallholder farming systems people practice a mixed farming approach and use available natural

resources in the commonages. Access to resources (land, water and natural resources) depends to an

extent on what and how much is available and on the local arrangements that are in place, which are

managed through the traditional and local authorities. In theory, everyone has access; in practice this

translates to those who can leverage resources through individual influence and resourcefulness.

Mixed farming in communal tenure areas consists of homestead plots, fields and communal grazing for

livestock.

Homestead plots, as the word indicates, are situated around the farmers’ homes and range in size

from around 500 m2 to around 0,5 hectares. These plots may or may not be fenced and in the more

formally planned villages will have some access to a municipal supply of water. Water supply however

is severely restricted in most cases to the municipal allocation of 20 litres per person per day – and only

if that water is available. Shared, communal standpipes outside people’s yards are the most common

form of access to water. This means that for around 90% of smallholders, they only have access to as

much water as they can carry to their homes on any given day. This water is used primarily for

household needs. This means that dryland cropping is still common even within homestead plots and

that more intensive productive activities such as vegetable and fruit production and rearing of small

livestock usually is done only if additional sources of water can be accessed, either through the

municipal systems, which is not common, or through access to springs and streams nearby. A very

limited number of individuals have their own boreholes.

19

Fields are generally allocated to individuals and are often not in direct proximity to the homesteads.

Sizes range from 0,1-5 ha, averaging around 1 ha in size. Historically these have been used primarily

for field cropping grains (maize, sorghum, millet), pumpkin species and legumes (sugar beans). Fields

may be fenced or unfenced and are worked by hand or by paying for private or government-based

mechanisation services. At this scale, a number of group projects exist in the communal tenure areas

and in some cases, projects run by government and non-government organisations have included

irrigation options. A very small percentage (around 1-5%) of individuals have set up their own irrigation

systems.

Communal grazing is managed on a village level and livestock are allowed to graze in and around the

villages and fields in winter months and adjacent veld, bush and hillsides during summer. Individual

smallholders often have kraals for their livestock and pay towards herding and dipping systems for their

livestock. Mostly these systems apply to cattle and sheep. In the past goats were not herded, but due

to increasing pressure on grazing areas and conflicts related to livestock destroying crops and gardens

this is becoming more common. Rangeland management is notoriously difficult in these communal

tenure areas and the quality and quantity of grazing appears to be in an almost continual decline.

Systems for fodder production, supplementary feeding and rotational grazing are not widespread.

Natural resources are harvested extensively for firewood, thatch, reed and grass crafts, food (e.g. wild

leafy greens) and medicinal purposes. Very few systems for control, management and regeneration of

natural resources are currently in place and in addition wide scale poverty and population pressure in

the communal tenure areas have led to overuse of resources and denuding of the commons.

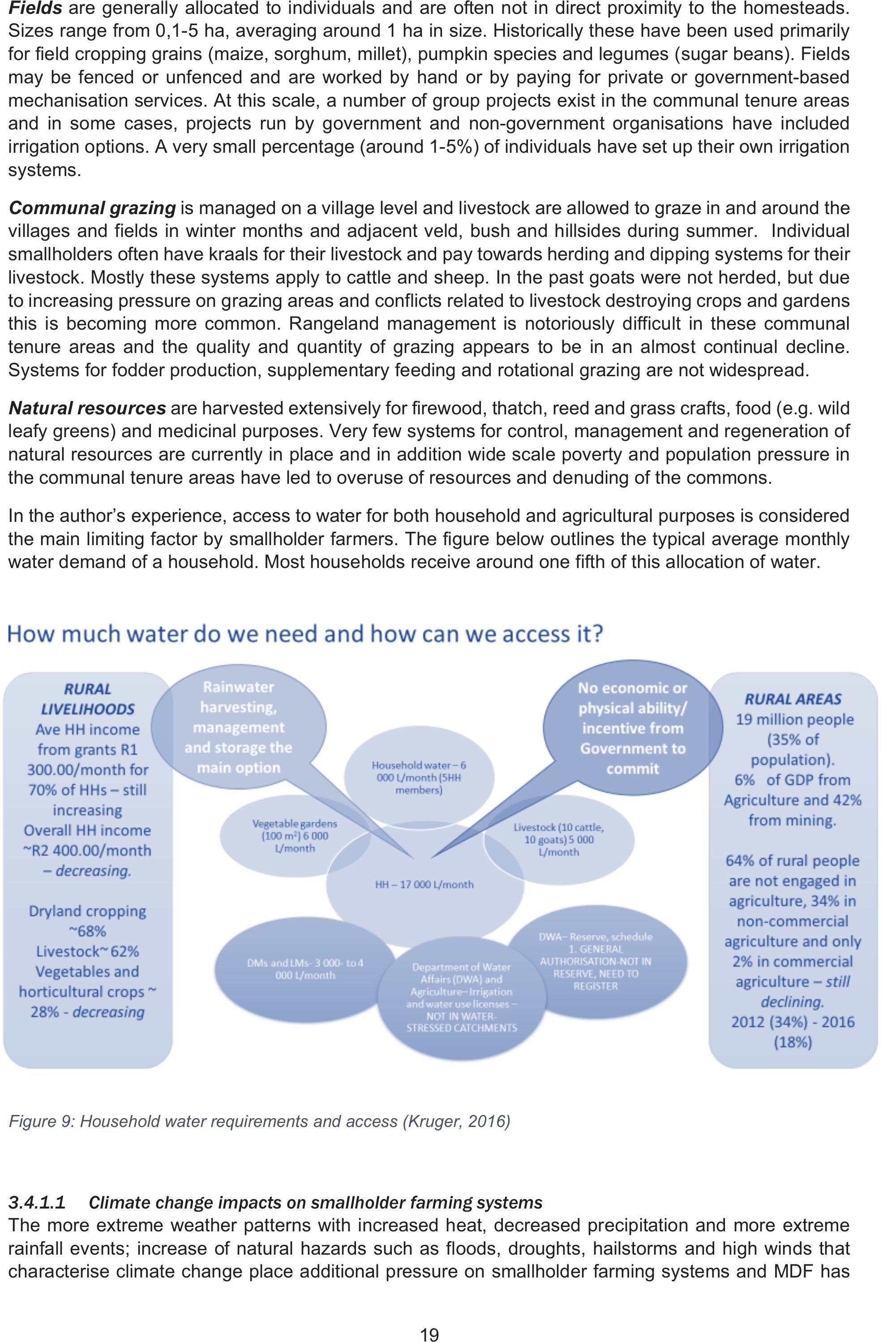

In the author’s experience, access to water for both household and agricultural purposes is considered

the main limiting factor by smallholder farmers. The figure below outlines the typical average monthly

water demand of a household. Most households receive around one fifth of this allocation of water.

Figure 9: Household water requirements and access (Kruger, 2016)

3.4.1.1Climate change impacts on smallholder farming systems

The more extreme weather patterns with increased heat, decreased precipitation and more extreme

rainfall events; increase of natural hazards such as floods, droughts, hailstorms and high winds that

characterise climate change place additional pressure on smallholder farming systems and MDF has

20

found that this has already led to severe losses in crop and vegetable production and mortality in

livestock. A significant proportion of smallholders have abandoned agricultural activities and this

number is still on the increase. Smallholders are generally not well prepared for these more extreme

weather conditions and experience high levels of increased vulnerability as a consequence (Manderson

et al., 2016).

It is becoming clear that climate change will have drastic consequences for low-income and otherwise

disadvantaged communities. Despite their vulnerability, these communities will have to make the most

climate adaptations (Fenton et al., 2015). It is possible for individual smallholders to manage their

agricultural and natural resources better and in a manner that could substantially reduce their risk and

vulnerability generally and more specifically to climate change. Through a combination of best bet

options in agroecology, water and soil conservation, water harvesting, conservation agriculture and

rangeland management a measurable impact on livelihoods and increased productivity can be made

(Hansford, 2010.)

3.5 LOCAL AND TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE IN CRA

Most of the CRA practices with which the project will be concerned are likely to be quite site-specific,

which makes local and traditional knowledge extremely relevant for implementing such practices at a

ground (community) level. It should be acknowledged that some of the CRA practices correspond with

many existing local practices. Local and traditional knowledge is deeply embedded in many

communities and the associated practices are considered cost effective and easy to scale out to other

communities.

The literature indicates that for adoption of CRA practices to be successful it should be built on existing

local and traditional knowledge (FAO, 2013). However, local understanding of the practices and reasons

to take up a practice often differs to that in the scientific domain. It is important for development

practitioners and researchers to have some understanding of the local and traditional knowledge to

allow better implementation of improved practices (e.g. CRA practices). Building links between the

scientific information and local and traditional knowledge presents a potential opportunity for developing

a holistic approach for dealing with the negative impacts of climate change at community level. The

Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD) is implementing a programme to increase

resilience in the Olifants River Basin – the approach, involving systemic social learning, is one example

of this (Kruger and Selala, 2017) (AWARD, 2017).

It is important to note that the depths of such knowledge and the implementation of such practices

varies considerably between communities in different areas across South Africa. In areas with a long

continuous tradition of indigenous agricultural practices, such knowledge is strong and the practices

well understood. Such areas include much of Limpopo Province, and the coastal sections of the former

Transkei homeland in the Eastern Cape Province, historically inhabited by the amaPondo and

amaThembu clans. However, in many other areas – such as those to which people were forcibly

relocated during the establishment of the former homelands – there is not such a long continuous

tradition and many of the farming practices have been derived from people’s acquaintance, often as

farm labourers, with the conventional agriculture practiced by the white commercial farmers. Even in

these areas, however, it is possible to find traditional practices such as ‘matamo’ (construction of small

ponds) or ’gelesha’ (ripping the ground to improve infiltration, prior to planting) (Denison and Manona,

2007).

Communities are already needing to use local, traditional and indigenous knowledge to help cope with

the negative impact of climate change. This includes knowledge of food preservation techniques (e.g.

fermentation and sun drying), knowledge of indigenous plants (e.g. for use in natural pest control), seed

selection to avoid drought and disease control in livestock. The list below shows some other local and

traditional practices which correspond with CRA principles and practices:

¾Seasonal weather forecasting (Use of shift in seasonal migration for birds as an indicator

for weather forecasting)

21

¾Selection of seed to avoid the risk of drought and pests

¾Water harvesting techniques (e.g. roof water harvesting)

¾Use of ash for seed preservation

¾Soil and water conservation using planting basins, furrows and ridges

¾Use of sunken and raised beds to accommodate for water holding capacity and soil types

¾Mixed cropping or intercropping and diversification

¾Use of supplementary feed for livestock

¾Preservation of pasture for use by young, lactating and sick animals in cases of drought

¾Transhumance to avoid risk of livestock loss

¾Culling of weak livestock for food

¾Diversification in the herd to survive climate extremes (Kruger and Selala, 2017).

CRA may provide a valuable opportunity to revive local and traditional knowledge and practices, as

they have considerable potential for amelioration of some of the negative impacts of climate change on

small-scale agriculture.

22

4 DECISION SUPPORT PROCESSES

This project aims to design a framework of methodologies, associated processes and a selection of

best bet practices, informed by the issues that have been discussed, which can be used to assess,

implement and monitor likely local CRA strategies. The practices themselves are discussed in the

accompanying handbook.

Within the climate change community, decision support systems for climate smart agriculture options

at a local level have thus far been designed in top-down processes – using climatic, geographic and

demographic databases and information to select a range of appropriate practices on regional level as

for example through USAID, Care International and FAO. Generally, a DSS is currently seen as a

computer, or perhaps more saliently, internet-based system, which enables large amounts of diverse

information to be analysed in order for managers to reach rational decisions.

A recent review, discusses the different types of models presently available and along with equation-,

agent and geographic-based models, discusses more participatory models as well (Nay, Chu,

Gallagher and Wright, 2014). Their conclusion is that it is advisableto adopt approaches incorporating

both technical and social components in a DSS.

The Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), has developed a decision

support system for identifying appropriate CRA practices; described as a set of filters for evaluating

CRA options & establishing CRA investment portfolios for National and sub-national decision makers

donors, NGOs, implementers (CGIAR, 2017).

Here however, we are focussing the decision support process on a bottom-up approach, where

individual farmers in a locality make decisions regarding the ‘basket’ of CRA approaches and practices

most suited to their specific situation. To do this in a way that also includes the concepts of social

learning, innovation and agency the following decision support concept has been developed.

4.1 WHAT GOES INTO THE CRA SMALL SCALE FARMER DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM

Using a systemic approach and social learning from a socio-ecological perspective, the model consists

of a number of layers of input parameters or filters used to define a basket of best bet CRA options for

a specific smallholder farmer, using a combination of participatory processes linked to technical

databases.

23

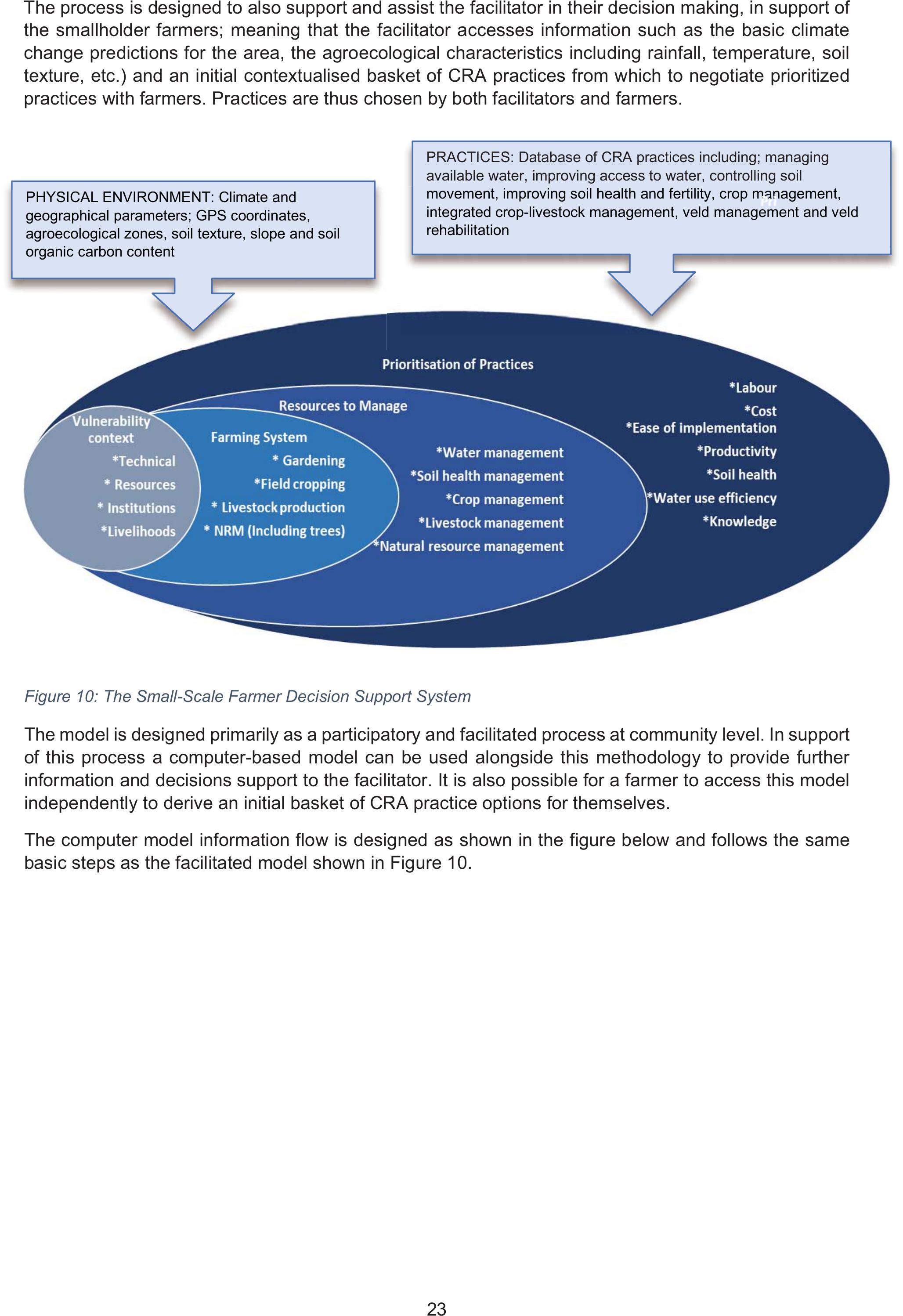

The process is designed to also support and assist the facilitator in their decision making, in support of

the smallholder farmers; meaning that the facilitator accesses information such as the basic climate

change predictions for the area, the agroecological characteristics including rainfall, temperature, soil

texture, etc.) and an initial contextualised basket of CRA practices from which to negotiate prioritized

practices with farmers. Practices are thus chosen by both facilitators and farmers.

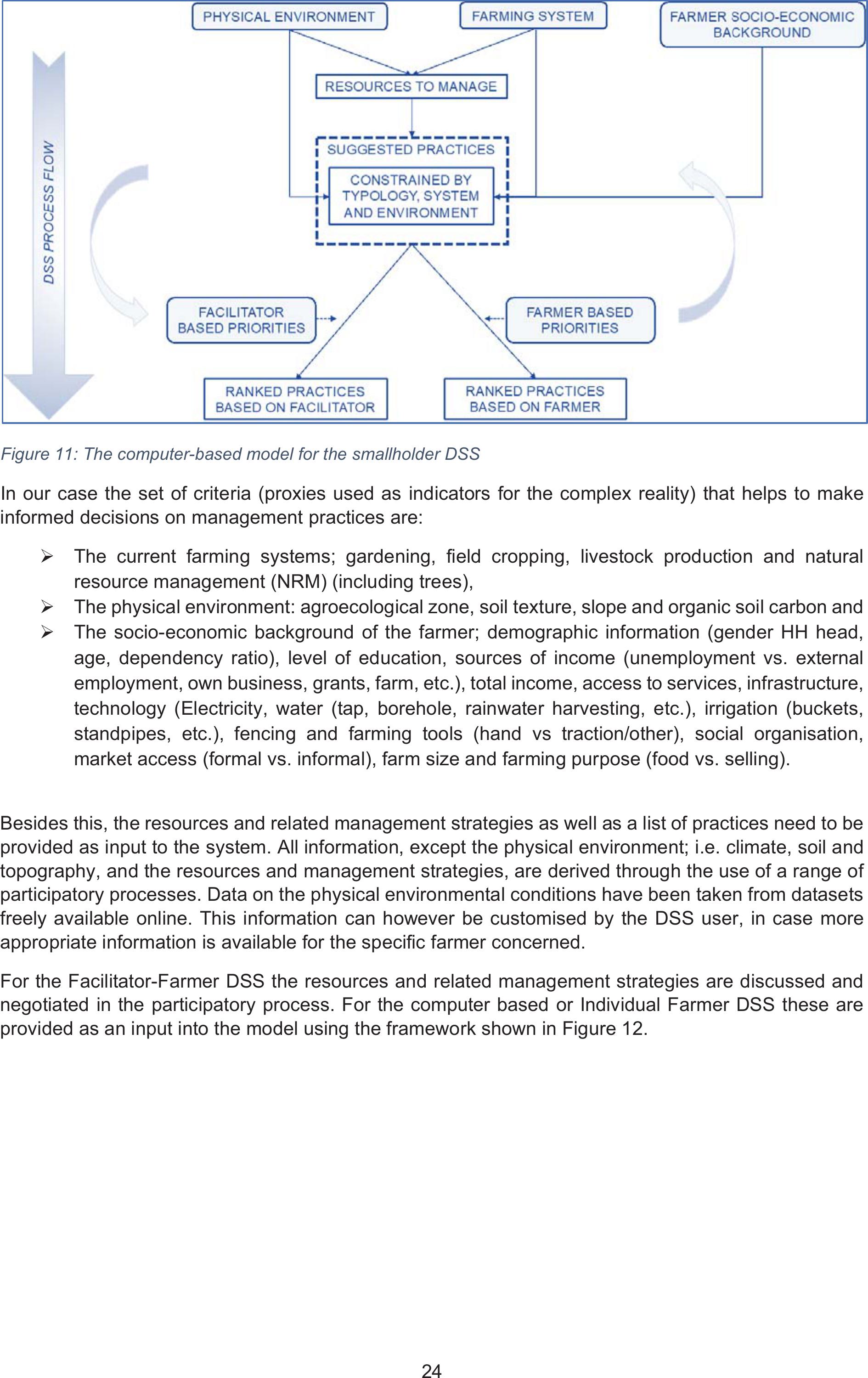

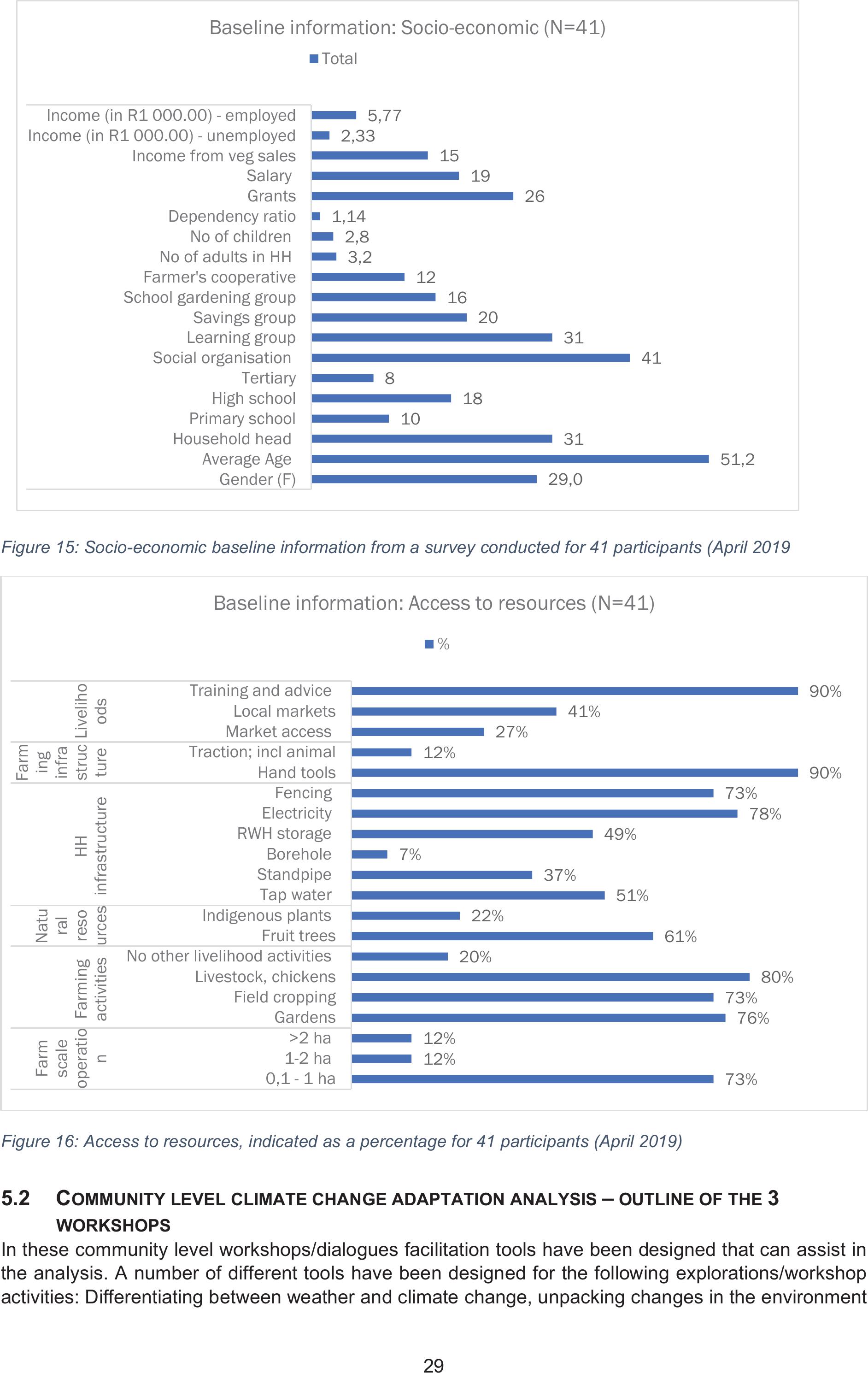

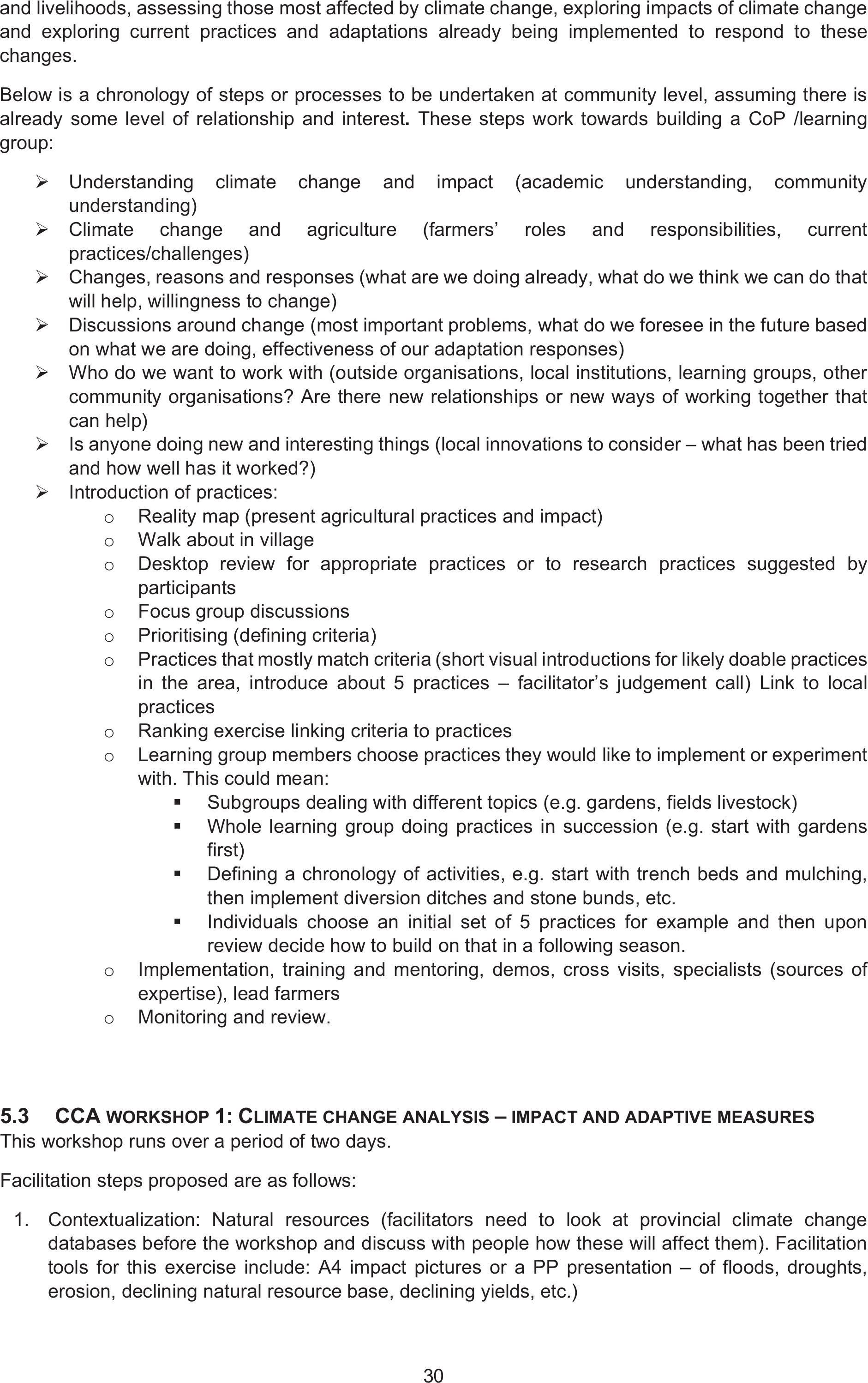

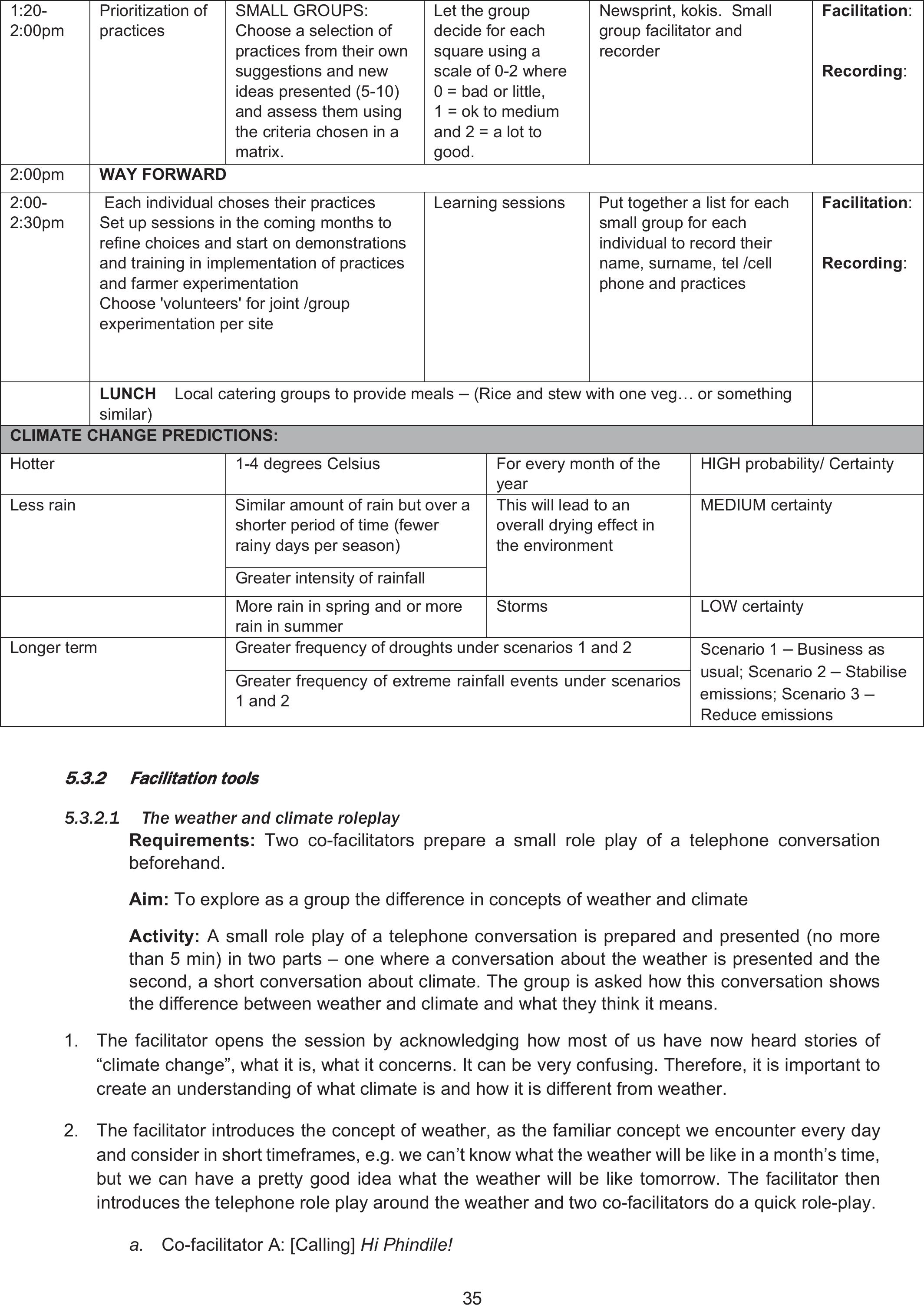

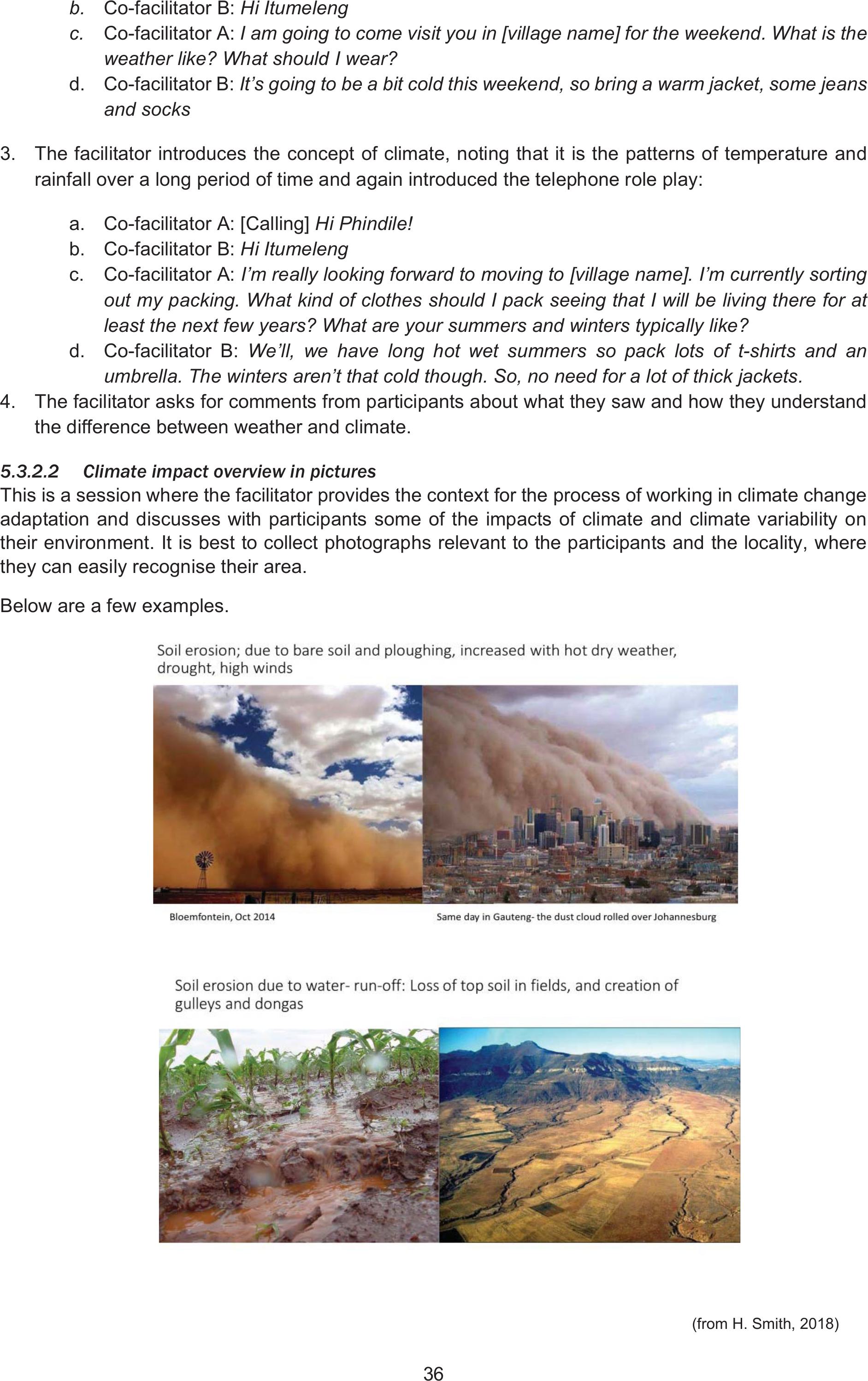

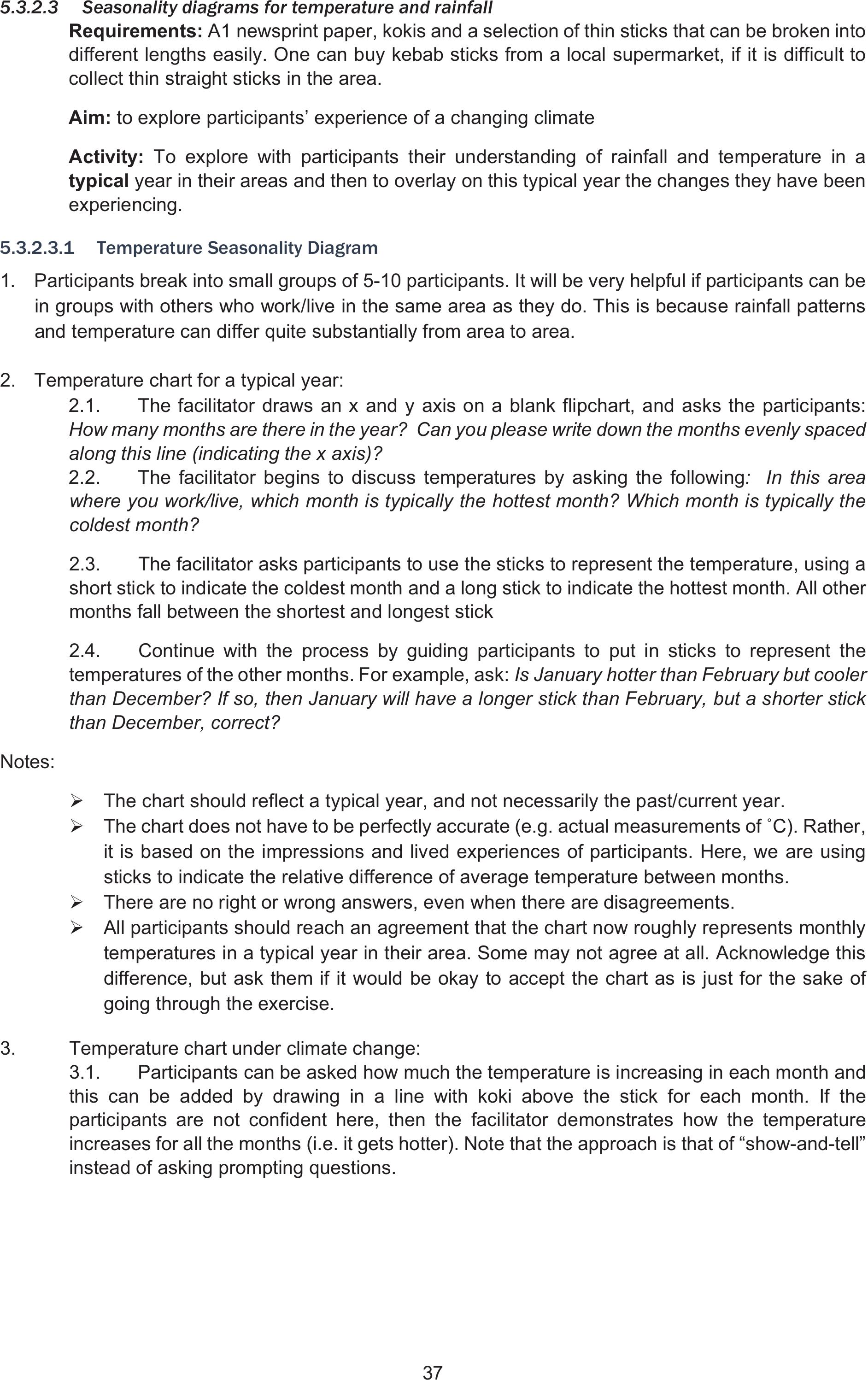

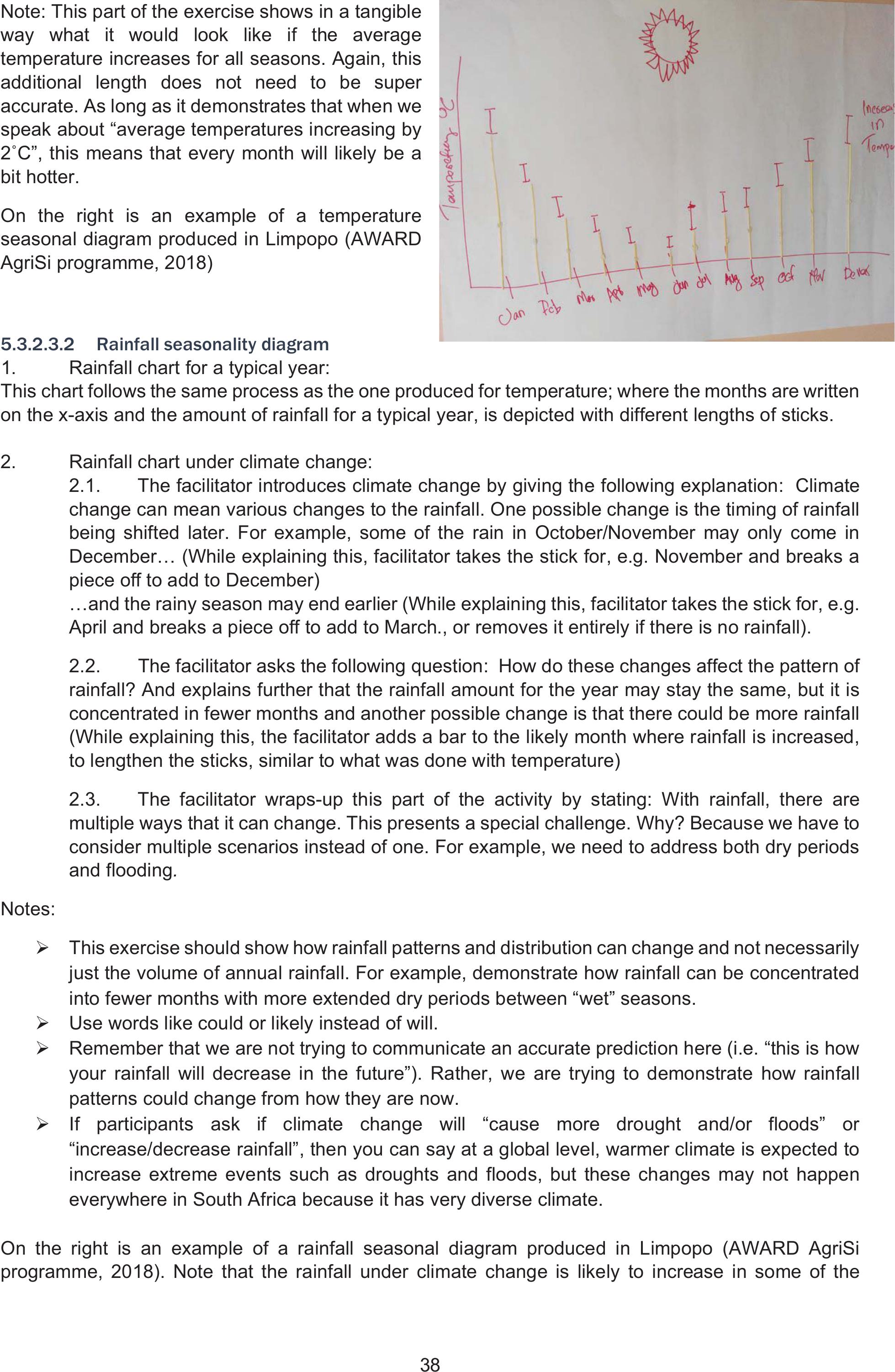

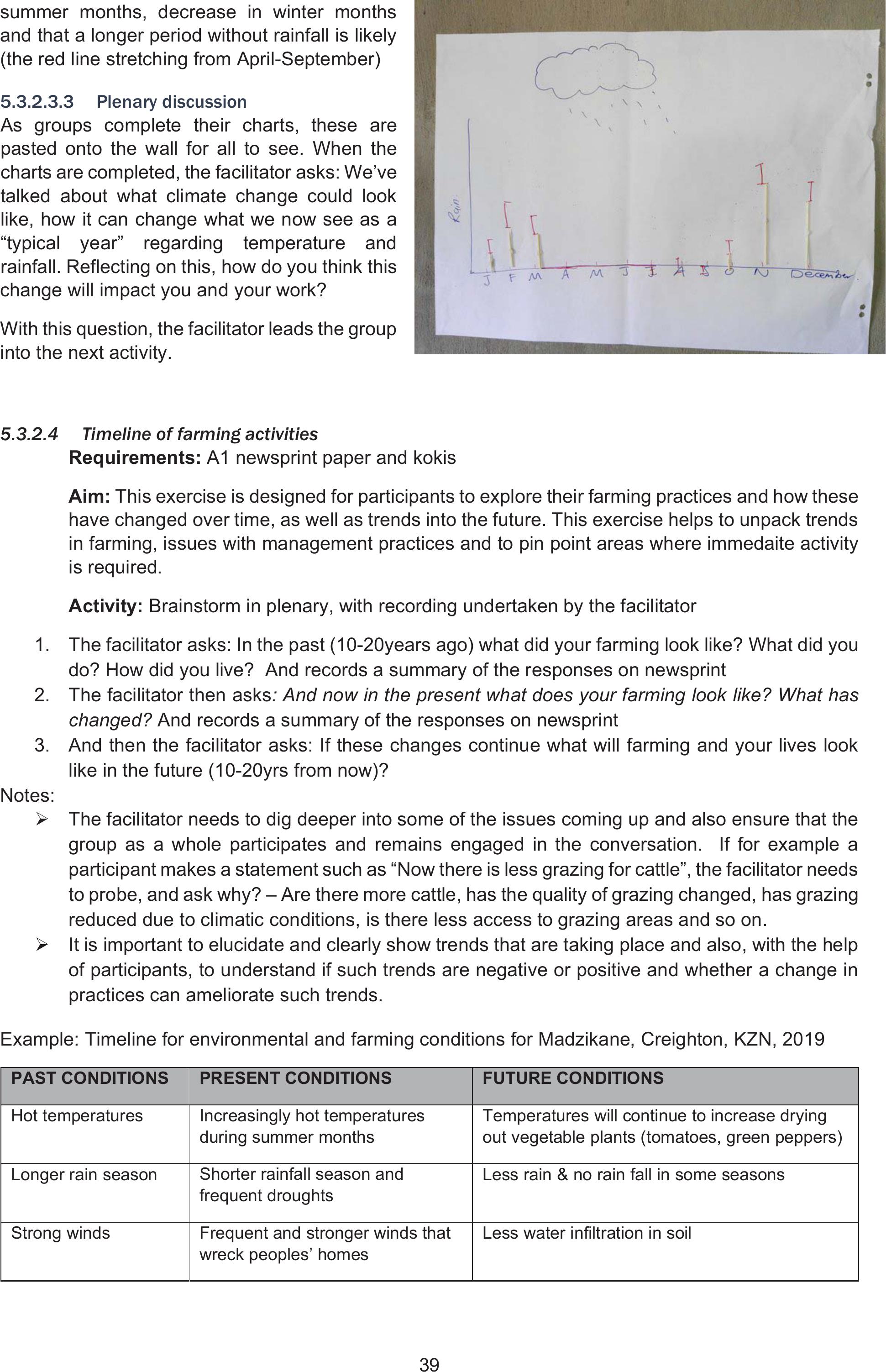

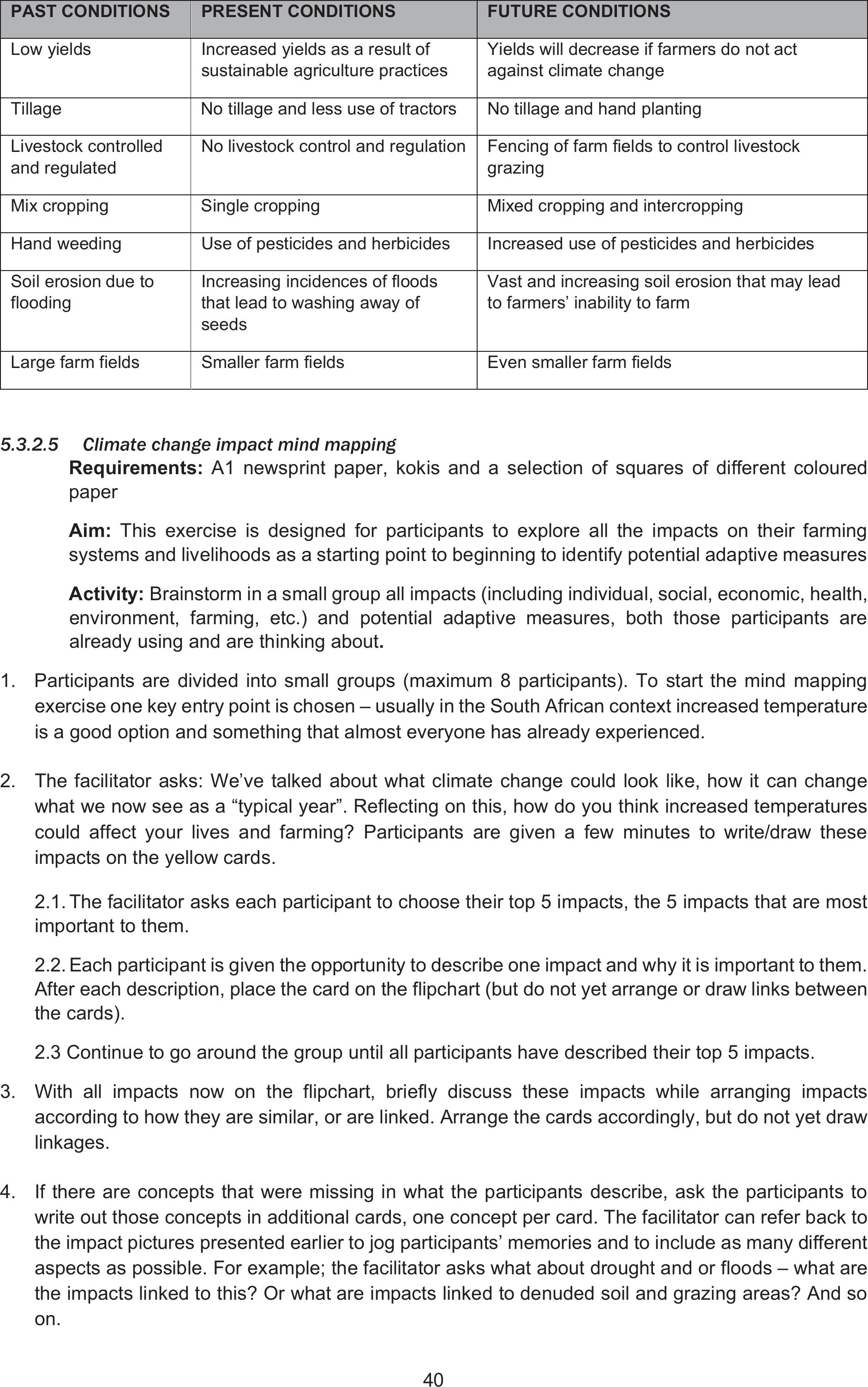

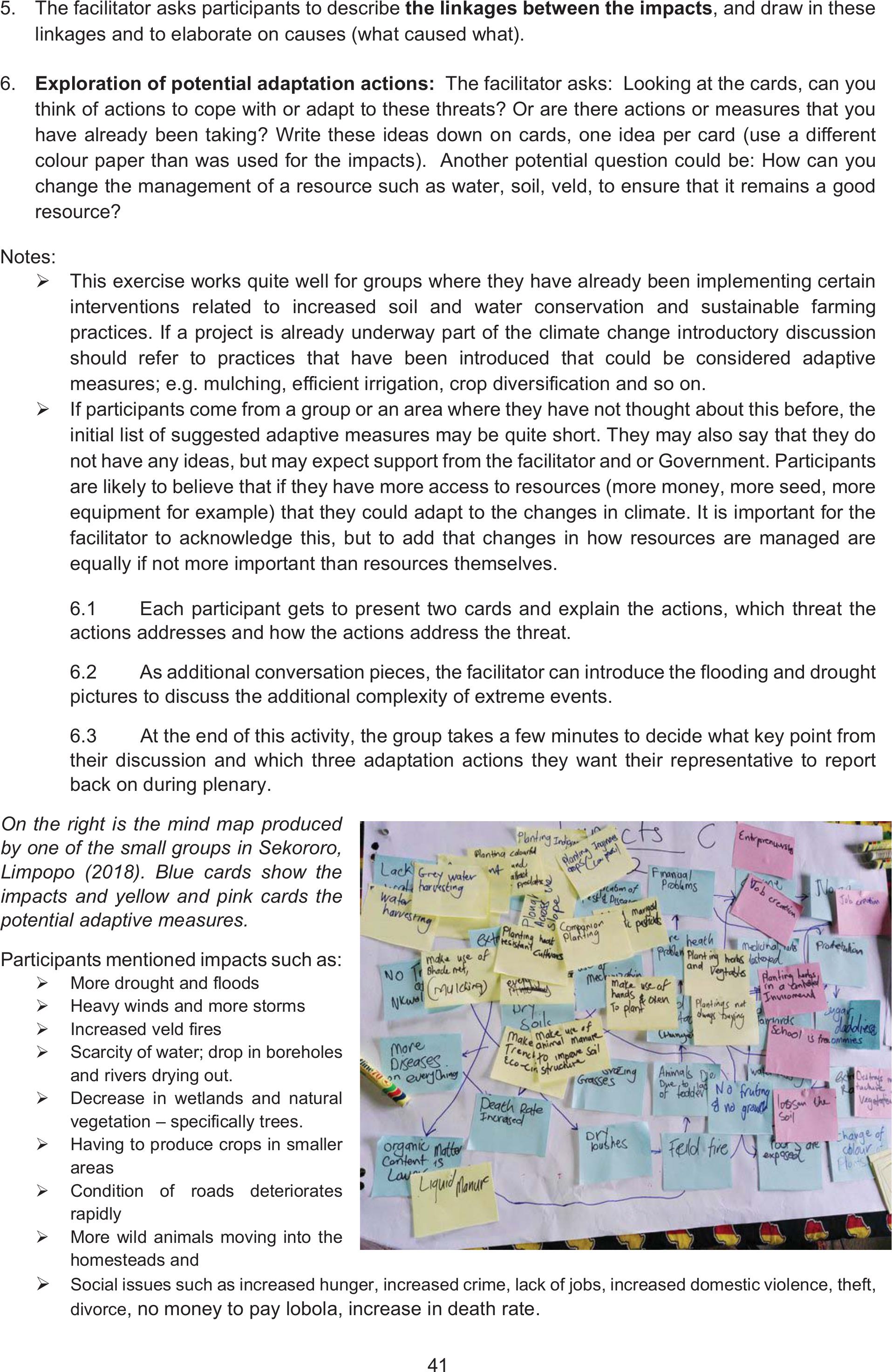

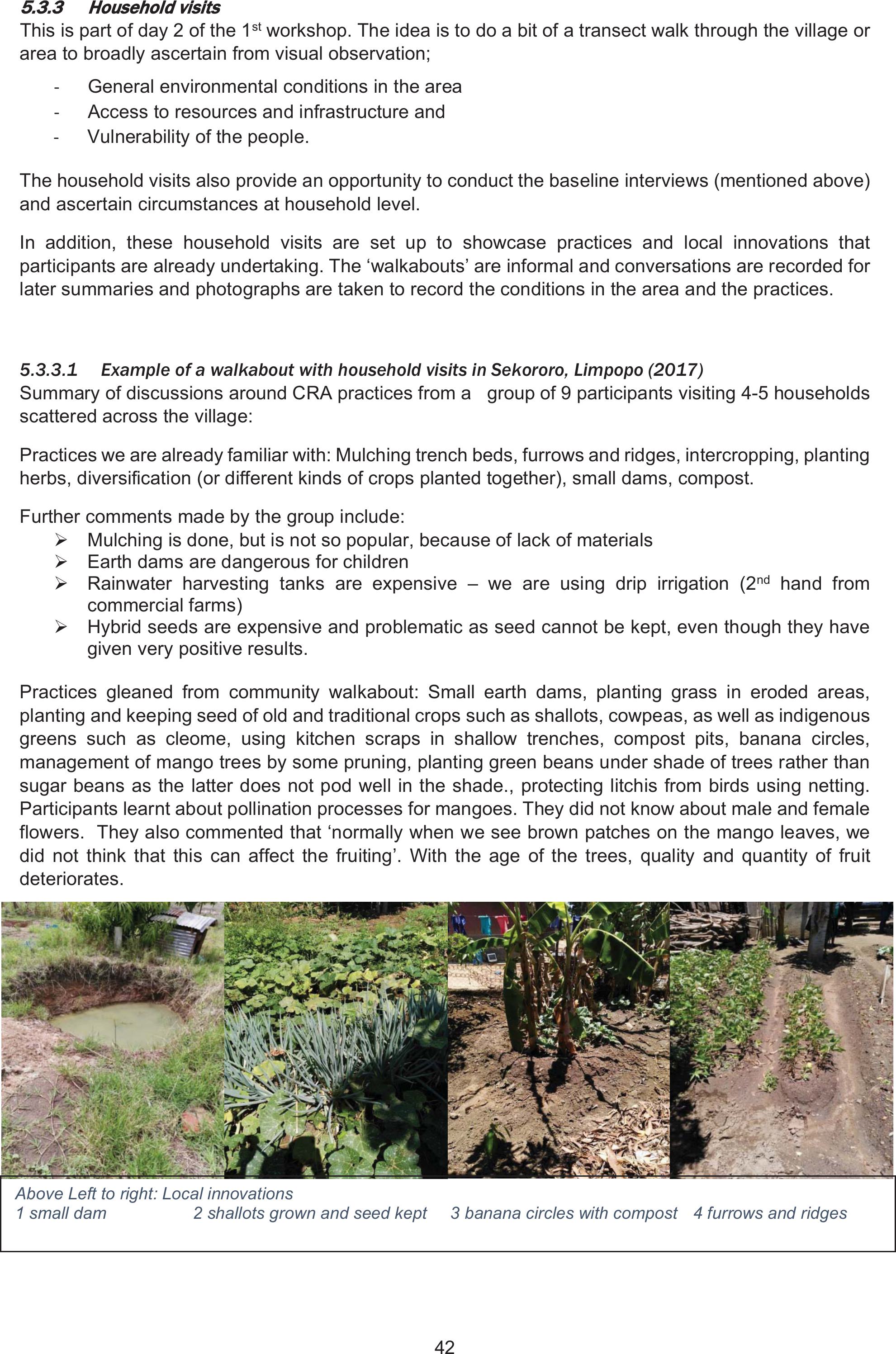

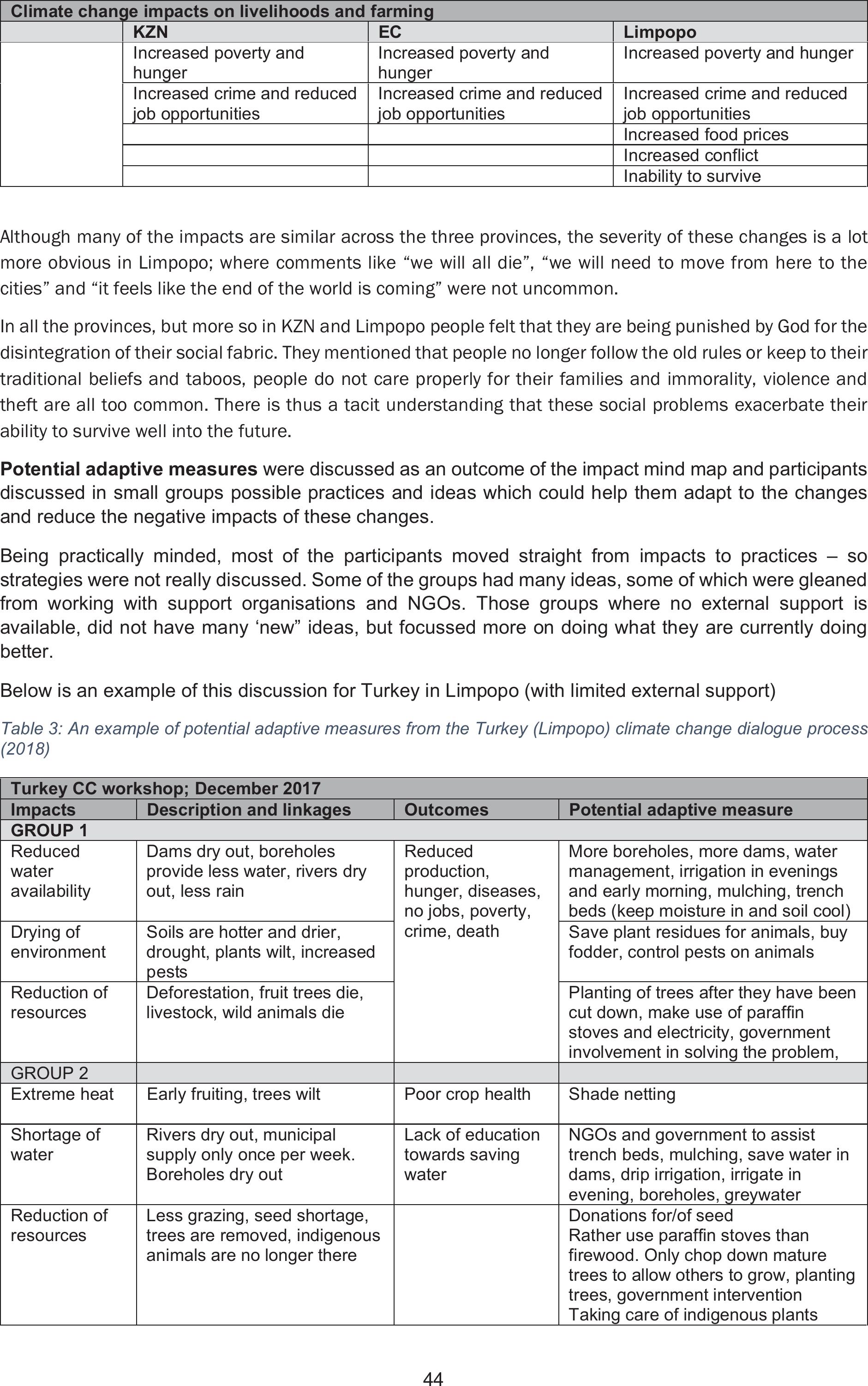

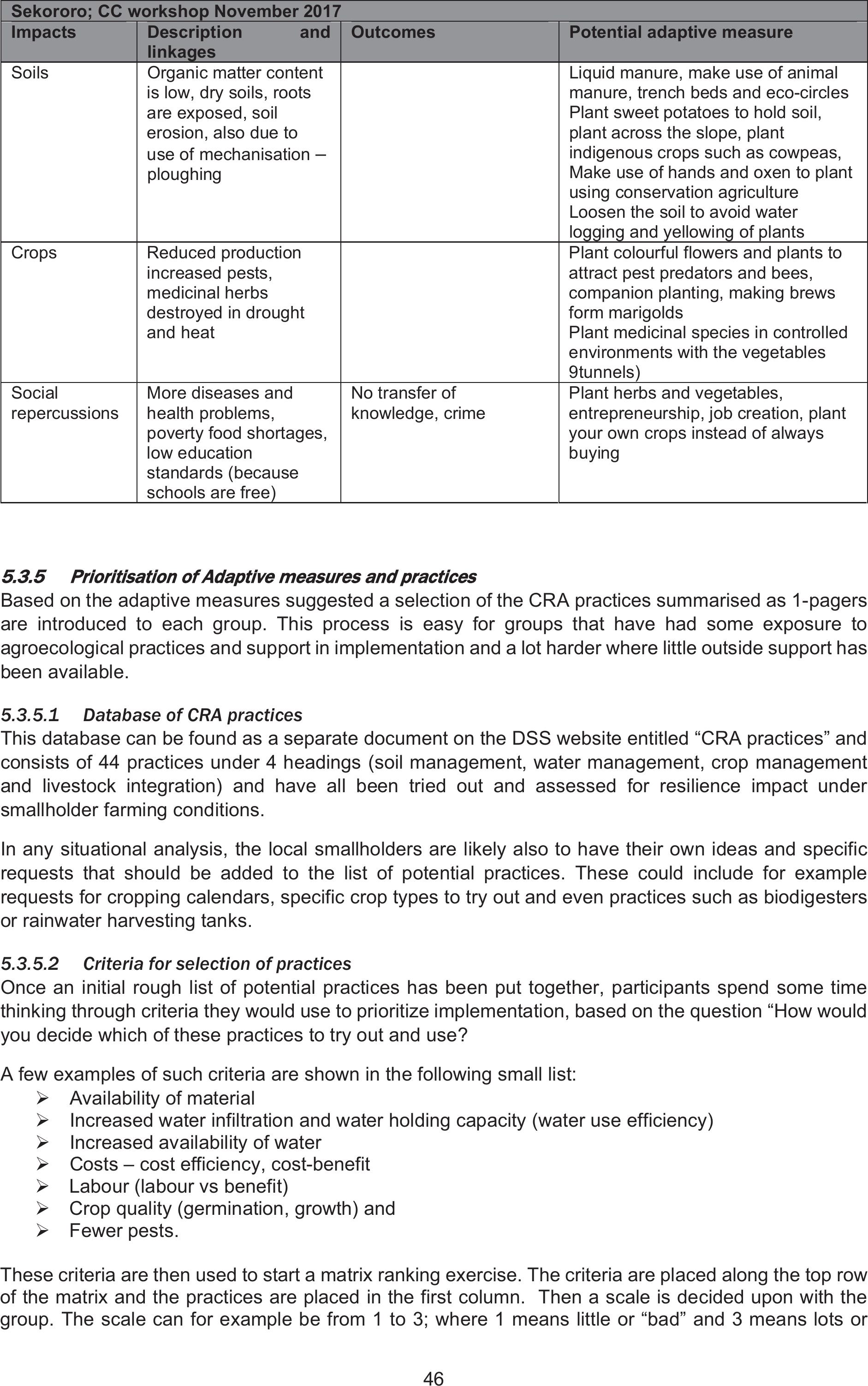

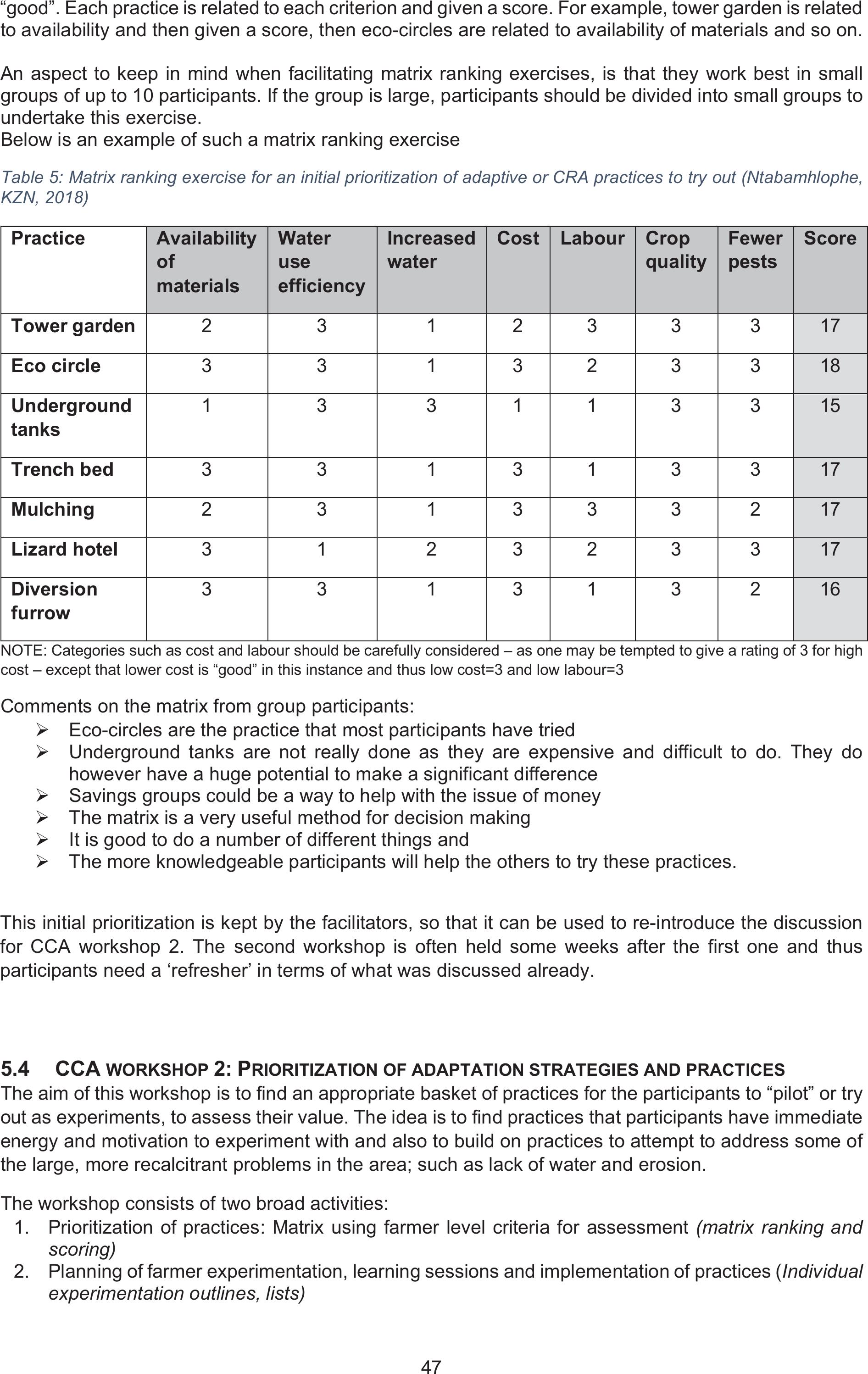

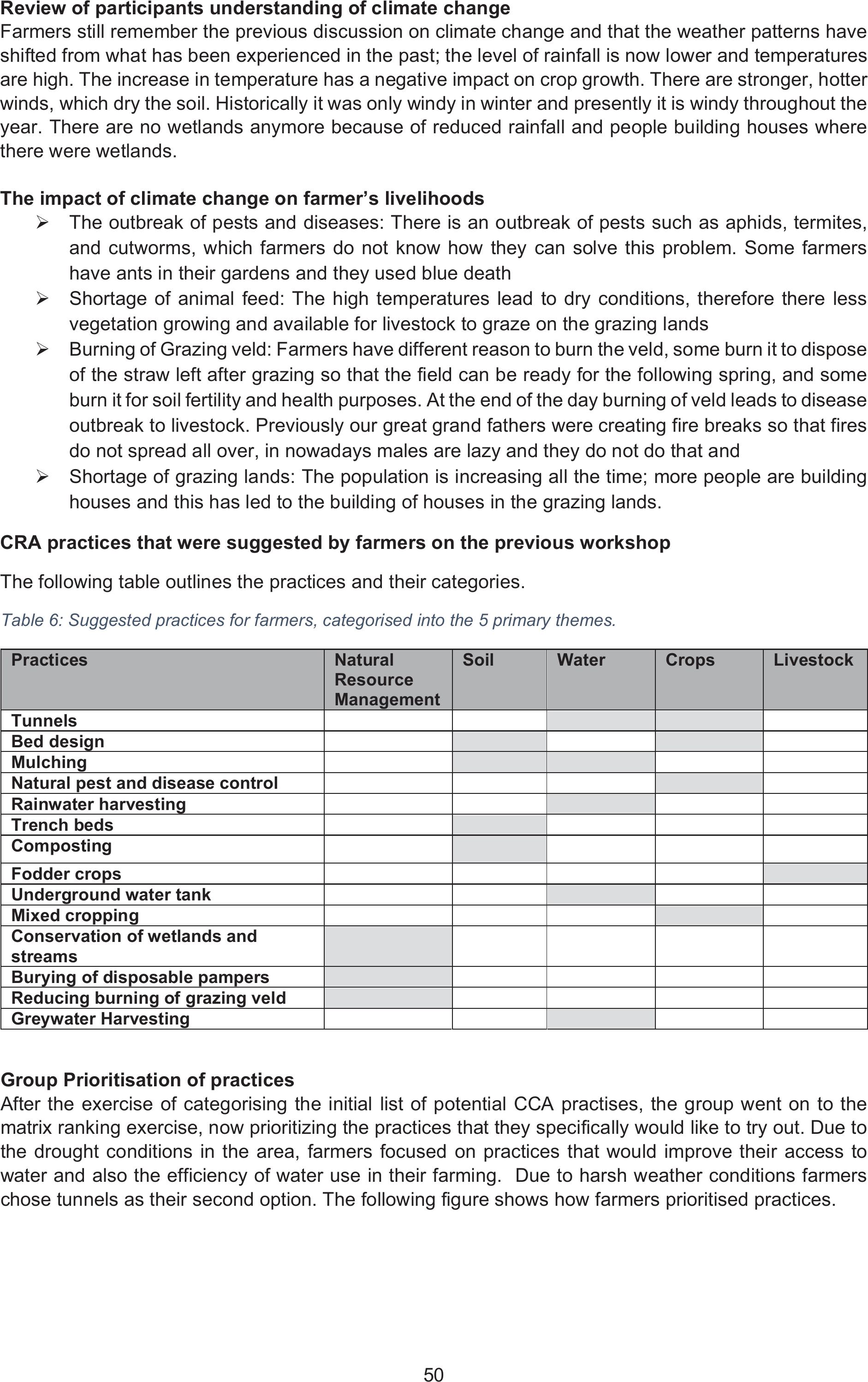

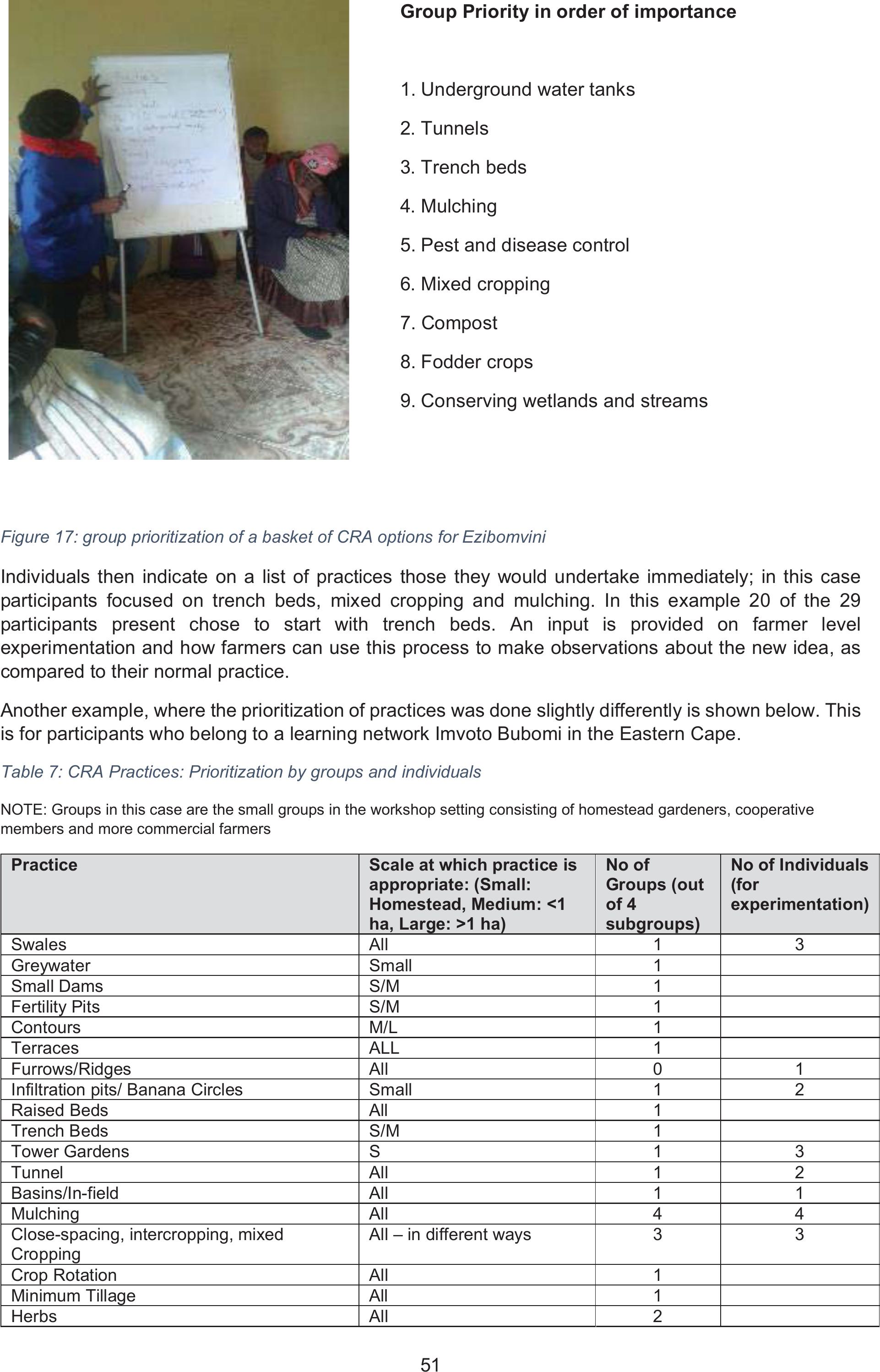

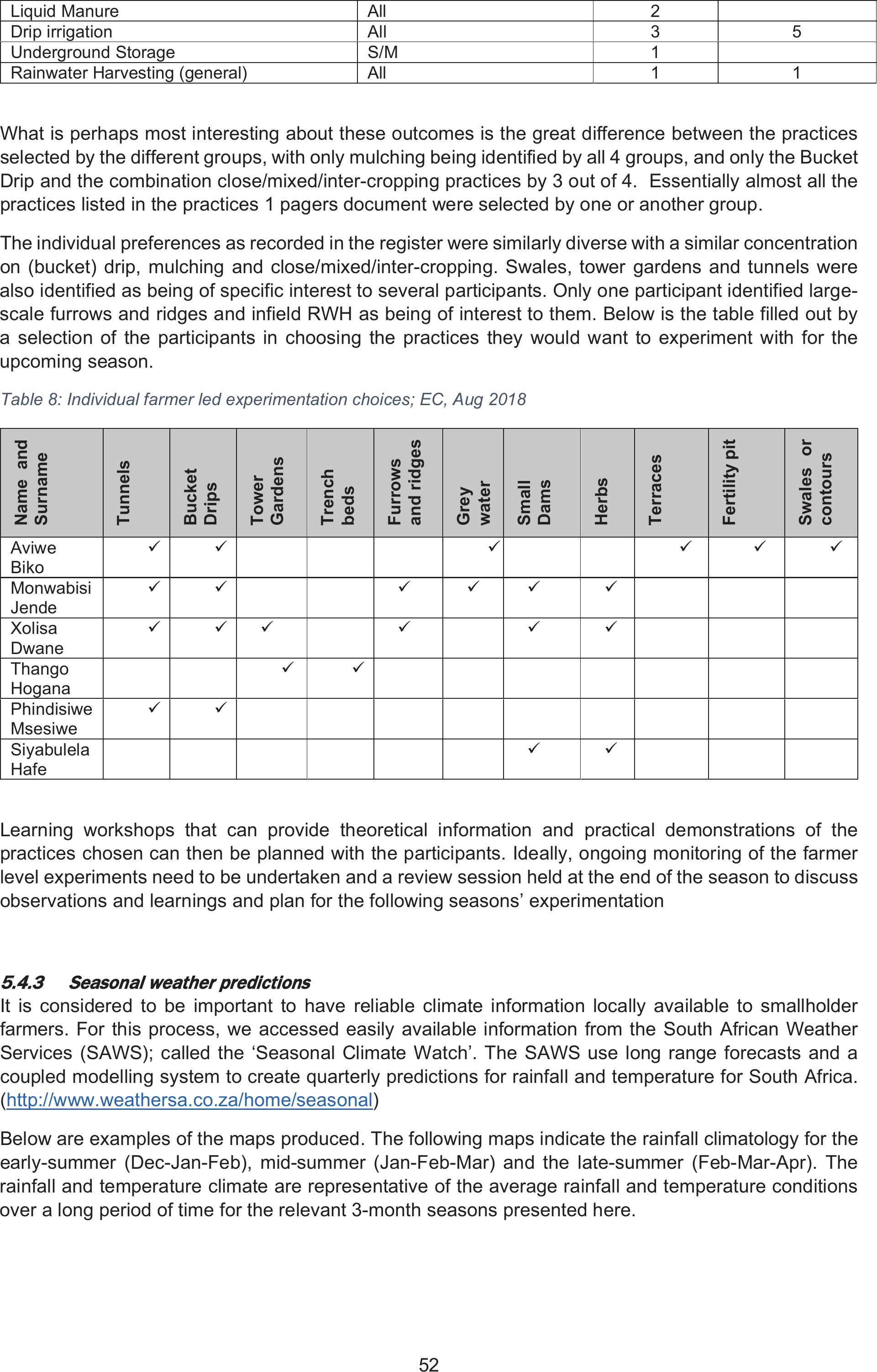

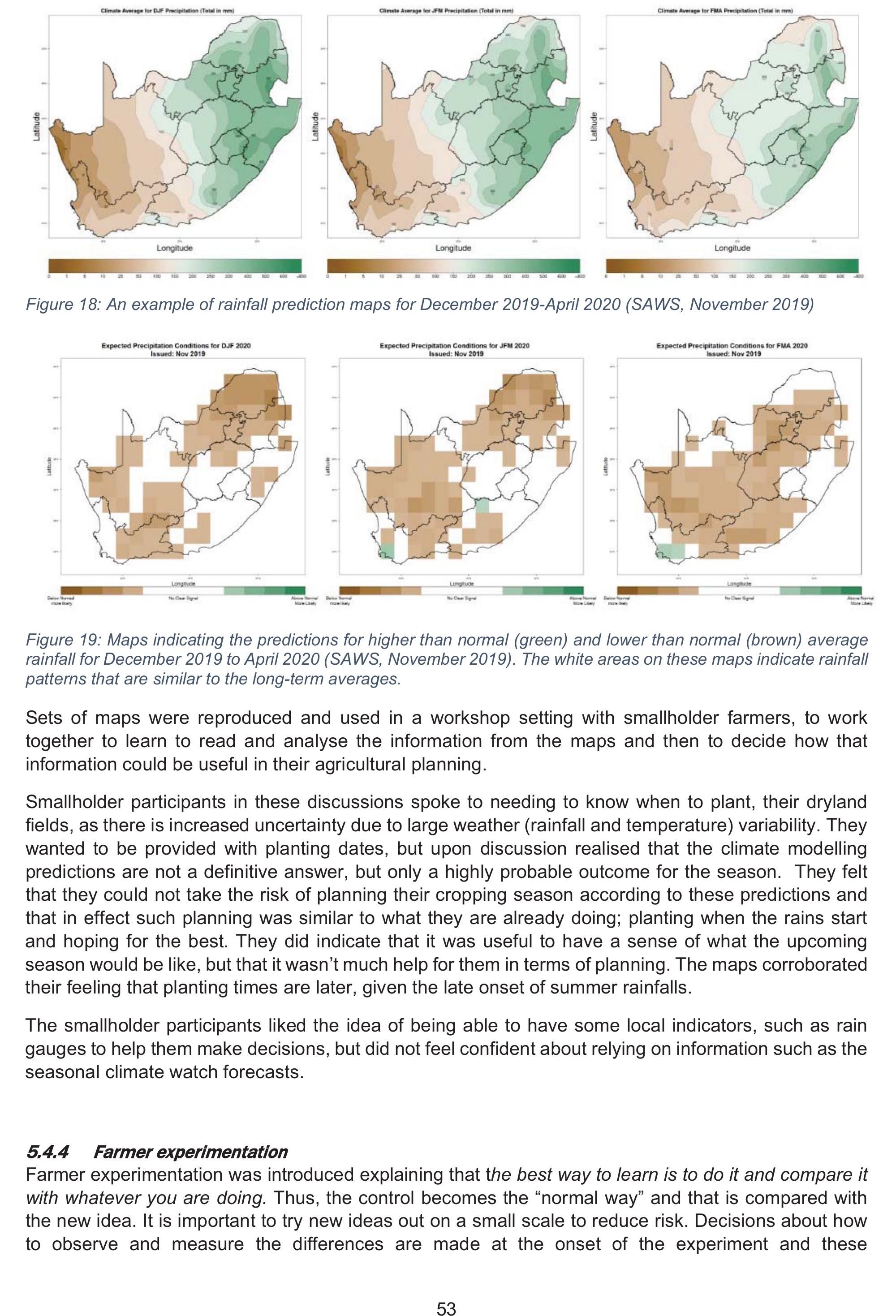

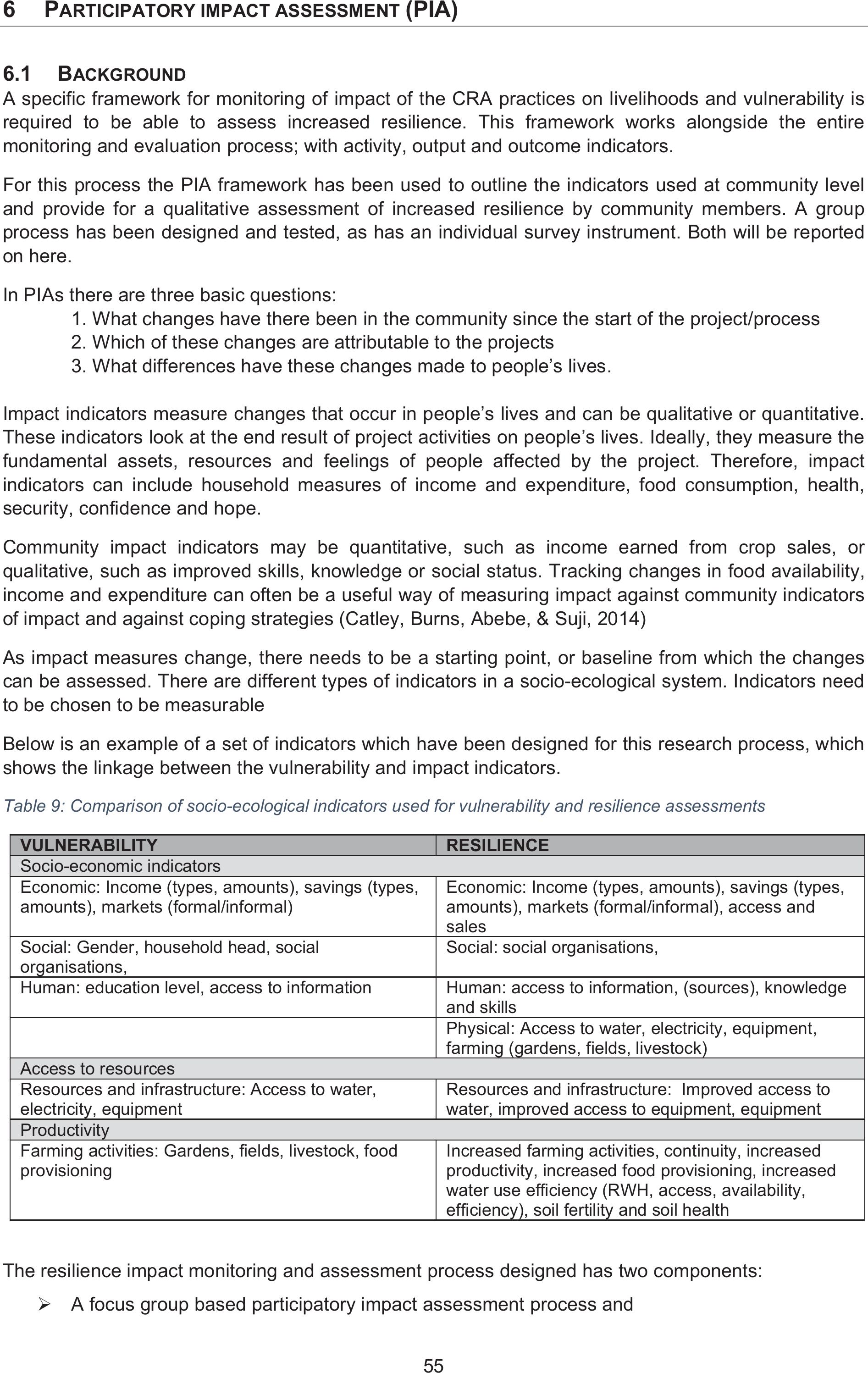

Figure 10: The Small-Scale Farmer Decision Support System