Participatory Market SystemAnalysis

for Saving and Credit Groups around

Matatiele, Eastern Cape.

AUTHORS

Contact: Anton Krone, Erna Kruger

Tel: 082 8537812, 0828732289

P O Box 84, Pietermaritzburg 3201, South Africa

123 Jabu Ndlovu Street, Pietermaritzburg.

anton@saveact.org.za, www.saveact.org.za, erna@mahlathiniorganics.co.za

ABSTRACT

A participatory market chain assessment was initiated in 2010 in the Alfred Nzo District

Municipality of the Eastern Cape (Matatiele, Mount Fletcher), to augment the work of

SaveAct with the savings and credit groups (SCGs) in the area. A recent study on livelihood

strategies and enterprise development found a strong relationship between participation in

SCGs and enterprise development. Early indications are that SCGs show a natural

progression from saving for consumption to saving for productive activities as the groups

mature. Small agricultural enterprise expansion is constrained by market chain pressures such

as high input and transport costs, inefficient production techniques and lack of marketing

options.

The participatory market chain learning and action methodology laid a foundation for a joint,

systematic analysis of agricultural potential, production and marketing processes and options

for the SCG members. It helped catalyse institutional arrangements where farmers could

work together to take advantage of what they had learned.

Local market opportunities in the villages are extensive and demand for food is presently

much greater than supply. Six agricultural commodities were prioritised:poultry, potatoes,

sheep, livestock, vegetable greens and maize. Initial market maps were produced for each and

used as a basis to deepen stakeholder interactions and to address some of the most pressing

challenges and opportunities in the market systems.

Commodity interest groups (CIGs) were set up. These groups explore: production efficiency,

financial and business management skills and options for cooperative activities such as bulk

buying, management of group processes around loans and savings, consideration of joint

marketing and transport arrangements.

CIGs have progressed in a number of different ways, including setting up joint input

procurement systems, increased use of specific systems for saving for productive activities,

increased local marketing and exploration of value adding and marketing options.

Stakeholder interactions and building of positive relationships with commercial and

institutional role players remain important. An initial focus on private sector stakeholders and

membership based organisations has provided a good opportunity for interaction with

smallholders.

KEYWORDS

Value chain analysis, savings groups, financial services, , savings-led enterprise

development, microsavings, credit, smallholder agricultural innovation.

1. INTRODUCTION

SaveAct works with communities to establish self-selected savings and credit groups (SCGs),

where members meet monthly to save and allocate loans from the capital fund of

accumulated savings. At the end of a savings cycle (1 year), members benefit from a

substantial share-out of capital, with groups typically generating annual returns of more than

30% on savings through interest charged on internal lending. Many groups operate social

funds to cater for emergencies.

SaveAct uses a stepwise model, starting with group savings and credit then introducing

financial education and later enterprise development (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: A stepped approach for livelihood support offered through the SaveAct model

Groups are trained in the savings methodology and savings meetings are facilitated and

monitored by field staff and community-based promoters (CBPs)Mature groups are

‘graduated’ once they are working well and generally function independently after around 18

months. The stepped approach is based on the assumption that basic household financial

stability must be achieved before people are willing to risk engaging in enterprise activities,

which are also more likely to be successful when the household is able to meet basic needs.

SaveAct fosters economic literacy among participants in the SCGs (savings and credit

groups) and supports processes for increasing marketing efficiency and equity. Participatory

market chain assessment was thus set up in the Alfred Nzo and Joe Gqabi Districts (Matatiele

and Mount Fletcher) as a local concentration of SCGs (almost 246 groups and 37 graduated

groups) exists in that area.

A progression from savings and credit for consumption purposes to productive elements is

appears to be observed. Saving and credit for productive purposes is supported. This has

taken the form of addressing efficiencies in supply, (through for example bulk buying and

supply chain management), increased production (through training, mentoring, advice and

farming system development) and marketing (including elements of processing and local

trading). An emphasis on social systems that can support these processes is seen as important.

2. METHODOLOGY

Working within a participatory market chain learning and action methodology (PMCL)

provides an ongoing process platform for engagement amongst beneficiaries, business and

institutional stakeholders. The process followed is a combination of a few different

approaches in participatory market chain analysis, namely the Participatory Market Chain

Approach (PMCA) promoted by CGIAR and the International Potato Centre (CIP) in Peru, a

Market Mapping process promoted by Practical Action(Albu and Griffith, 2006) and a

marketing scoping process developed by the NRI (Bennet et al., 2005). This has more

recently evolved into the PMSD – participatory market systems development, with the

PMCA evolved into PMSA (participatory market systems analysis) (Griffith and Osorio,

2008).

These methodologies promote a qualitative approach to market chain analysis, working with

local farmer interest, problems and ideas. The approaches are demand orientated and market

driven and include the actual implementation of marketing innovations. They respond to

collectively identified business opportunities. Research and facilitation input and support is

important throughout. Emphasis is given to bringing together actors from different

backgrounds such as traders, farmers, processors and institutions, who may or may not have

been in contact previously.

2.1 Overview of the process

The diagnostic phase of the Participatory Market System Analysis was combined with an

analysis of production potential and present agricultural activities and production in the area,

to provide the joint analysis for action within the savings and credit groups.

The market maps and prioritised agricultural commodities were then used to initiate joint

activities through the commodity interest groups that were set up. This involved negotiation

with market chain stakeholders, training and mentoring in agricultural and business

management and more efficient input supply options.

2.2 Description of methodology and process

The following steps were followed in building participation amongst farmers from SCGs: an

agricultural assessment, the diagnostic phase of participatory market system analysis,

commodity interest groups and a livelihoods strategies assessment. Each step is outlined

below.

Agricultural assessment Analysis of land capability and resource use including:

➢ Summarised information from the KZN Department of Agriculture Bioresource

Programme , Bioresource Units (BRUs)

➢Information on local markets, producer capacity, access to support and

➢Information on present production systems and capacity.

Methods and tools:

Desktop study, individual and group interviews.

PMSA-Diagnostic phase: Investigation of targeted market chains and their actors and

identification of potential innovations (commercial, technical, institutional) based on the

shared interests of the stakeholders involved. Activities in the diagnostic phase included:

➢Scouting in the area to identify nodes, farmers and potential market systems, to set up

initial interactions with relevant stakeholders and to include available reports and

desktop information.

➢Identifying commodities and market chains.

➢Market scoping and mapping exercise on community level - based on nodes and

proximity to specific towns (Matatiele, Mount Fletcher and Kokstad).

➢Preliminary market maps for chosen commodities outlined: including community

process, qualitative interviews with farmers for each node and qualitative interviews

with marketing stakeholders, NGOs, government institutions.

➢Overview of thematic opportunities – to be used in subsequent workshops and

presentation of results.

Methods and tools:

Market Scoping (Bennet 2002) – To help people understand their marketing

environment. This involved market mapping, , marketing system analysis,

commodity ranking and participatory value chain analysis.

oMarket Mapping: To identify market chain actors and linkages, factors

enabling the business environment, business and extension service providers

(Practical Action 2008). The market maps provide a framework for

conceptualisation of a market literacy approach as a component of rural

livelihoods interventions.

oCommodity ranking: A group exercise using locally defined criteria to rank

profitable commodities for the area.

oParticipatory value chain analysis: To help individuals and groups to analyse

and assess their best points of intervention for positive change in specific

commodity chains that they are involved in. They identify inefficiencies,

inequities and losses which could be remedied or added value which could be

captured.

Commodity Interest Groups (CIGs): Groups are set up to include members of SCGs in the

same locality interested in the particular commodity in order to:

➢Further analyse the commodity chain

➢Design appropriate actions and processes for the groups, and

➢ Set in motion actions around input supply, production efficiency and market

development and linkages.

Methods and tools:

oTraining and mentoring in: Small business development(Isiqalo,meaning

‘step up’) and aspects of production to improve efficiency and profitability

oDevelopment of input supply systems: Bulk buying systems and support,

transport, cooperation among group members, small business initiation and

support

oExploration of market system and opportunities: Explore local

cooperation to improve informal marketing systems.

Livelihoods strategies assessment to generate data (optional): consisting of the following

processes:

➢Questionnaire based interviews for approximately 150 SCG members,

➢Nine group discussions using Participatory Rapid Appraisal (PRA) tools;

➢Semi-structured interviews with key informants (2 in Matatiele); and

➢Case studies with local agricultural entrepreneurs in SCGs (8 in Matatiele)

Methods and tools:

oQuestionnaire based interviews, group discussions and case studies.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Agricultural assessment

The areas around Matatiele and Mt Fletcher fall into different Bio-Resource Units (BRUs)

that broadly fall within one larger Bio-Resource Group (BRG) known as ‘Dry Highland

Sourveld’ (BRG 9) (Camp, K.G.T, 1999).

The area lies in a temperate summer rainfall region, with approximately 75% of rainfall

between October and March. The mean annual rainfall ranges between 700mm and 850mm,

mainly in the form of summer thunderstorms. Mean annual run-off is very high, estimated to

be between 1600 - 3200 million m3.

Temperatures in summer range between 21°C and 28°C during the day and 18 °C -2 °C at

night. The area experiences cold winters with frequent frost and limited snow. This limits the

type of crop potential to summer and frost resistant types, taking into account late and early

frost threats, and a reduction in available heat units for optimal growth.

The area is generally high lying, between 1350 and 1750m and the topography is

predominately influenced by the geology of the basalt Drakensberg group, with some basalt

and sandstone outcrops. The majority of the terrain can be described as rolling with steep

hills and deep valleys along the escarpment to the north. Relatively flat areas are located on

the lower lying base of the foothills below the escarpment with Lesotho, which are wide

alluvial plains often dotted with permanent wetlands. The soil is generallywell drained in the

higher lying portions of the basin formed by the upper Umzimvubu drainage area. A mixture

of clay and loam soil dominates the area and is rich in organic matter deposits. This makes

for fairly good soil for general crop production. High potential soils are not common, making

up around 7-10%. Arable soils for dry land crops are found in 15-20% of the area. Around

50% provides high potential grazing land. Irrigation is possible, but more suitable for

perennial crops than annual crops with around 20% of soils in the area being suitable.

Trees are limited in the natural grassland, and consist of exotic species planted for firewood

and material supply purposes, in the form of Eucalypt and wattle stands. There are no

indigenous forests but small pockets of mist belt forest tree species occur in the higher lying

protected kloofs and ravines.

Overall, livestock production is to be favoured.Goats are not recommended as they have

heavy impacts on an already overtaxed resource base. Tree crops such as fruit, nuts and

timber are a good idea. Perennial crops such as pastures are also suitable, more so dry land

pastures. Annual cropping and specifically irrigated annual cropping is more limited to

suitable soils in the flood plain areas, where there is good potential. Attention needs to be

given to soil management and erosion control practices throughout - such as appropriate

contour protection.

Yield models for certain of the more well known crops suitable in this area are available

(Whitwell and Mitchell, 2010). Below, a table is provided to give an idea. The yield values

should be considered as a 10 year average. Accurate yield predictions are not possible

without comprehensive soil and land capability assessments.

TABLE1:CROP PRODUCTION POTENTIAL

Crop Name: Common crops

Average yield

(tons/ha)

Crop name: Alternative crops

Cabbage: Transplant Oct-Nov

87

Lettuce, Chicory

Cabbage: Transplant Jan

74

Barley

Carrot: Sow Nov

58-65

Apple, pear, peach and nectarines

(med chill cultivars)

Carrot: Sow Feb

30-40

Lemon, navel oranges, grapes, olives

Tomato: Transplant Oct

63

Blackberry, Raspberry

Dry beans

0.8

Lima beans, Lentils

Maize dry land

2.8-3.1

Chinese cabbage, mustard, swiss chard

Oats dry land

3.2

Sweet potatoes

Potatoes (Oct-Feb) dry land

26.3

Sage, Thyme,Pyrethrum

Wheat, irrigated

3.3

Walnut

Lucerne, irrigated

10

Cherry

Nodes or villages were identified within the region with the following criteria in mind:

•Established and new groups (SCGs)

•Concentration of groups for later clustering

•Different agro ecological zones (here defined as bio resource groups and units)

•Proximity to different centres or towns

•Potential for different farming styles:

oIntensive homestead production; diversity of vegetables and cereals, fruit

small livestock (chickens, ducks...)

oGroup projects; e.g. vegetable production, poultry, eggs,

oIndividual ‘emergent commercial’ farmers; cropping, livestock.

3.2 Participatory market assessment – diagnostic phase

Market Scoping: The process employed was to engage SCG members in a broader

community meeting in their area, in 4 nodes/villages (Khubetsoana, Mpharane, Nkau and

Masupa). As an example an overview of local market chains was developed in Khubetsoana

with a group of around 64 people. This is summarised below:

oNo formal or organised marketing processes exist in the village or the local area. In

the past there were livestock auctions (cows, sheep) at Queens Mercy nearby. These

have however been discontinued.

oThe only marketing that does occur is informal marketing by individuals. Produce is

sold to other individuals in and around the village. Competition is not a big problem

in the area, as demand outstrips supply in most cases. Otherwise individuals will

cooperate in terms of sales.

oPeople from outside Khubetsoana come to the village occasionally to purchase

cabbage, turnip, imifino (vegetable greens), potatoes, wool and thatching grass. The

price is lower for these customers considering transport and the fact that they buy in

bulk.

oSome people in the community transport imifino (especially turnip) to town and sell

there. Occasionally individuals group themselves together to facilitate transport to

sell maize or potatoes in town.

oSome community members have tried to form co-operatives to produce sheep, cattle

and maize on a commercial level. They have worked with the DoA and SEDA but

are still struggling to get registered in order to access funds available for co-

operatives.

oCrop production consists mostly of spinach, turnips, rape, cabbage, carrots and

imifino/ morogo (vegetable greens) in winter and maize, pumpkins, beans and carrots

in summer. Individuals sell surplus after providing food for themselves.

This picture was similar for all villages where the participatory market chain analysis was

conducted. This led to one of the primary recommendations of the process: to focus on local

and informal marketing opportunities and systems.

Commodity ranking: A participatory process of identifying agricultural commodities being

produced and sold in the area (Khubetsoana) was followed by ranking these commodities

using a list of criteria defined by the group. These commodities formed the basis for forming

and supporting commodity interest groups (CIGs) in the different villages.

TABLE 2:LOCAL MARKET CHAINS AND THEIR RELATIVE IMPORTANCE

Product

Criteria 1:

Demand

Criteria 2: Production costs

Criteria 3:

Disease or pests

Criteria 4:

Profitability

Total

Checks

No of

people

present

who sell

Estimated no

of people in

village who

sell

✓✓✓- always

high

✓✓-

seasonally

high

✓- seasonal

and not so

high

✓✓✓- does not cost a lot and

not too much labour or other

resources required

✓✓-fewer inputs, but high

labour requirement

✓- very expensive, includes

the need for a lot of different

inputs and lots of water and a

lot of labour

✓✓✓- Very few

diseases and pests,

easy to deal with

and cheap

✓✓- average

diseases and pests

✓- more diseases,

difficult to deal

with, expensive

✓✓✓- always

high

✓✓- seasonally

high

✓- seasonal and

not so high

Chickens

(white and

indigenous)

✓✓✓

✓

✓

✓✓✓

8

9

Imifino

(spinach,

greens)

✓✓✓

✓✓Doesn’t need to many

inputs

✓✓

✓✓✓

10

12

Sheep

(igusha)

✓✓✓

Local demand

is very high;

sheep are used

in all

ceremonies

and are even

more

important than

goats and

cows

✓

✓

✓✓✓

8

6

Pigs (Ihagu)

✓✓

✓✓✓

✓✓✓

✓✓✓Genera

lly easy to

manage but can

get swine flu

leading to

heavy losses

11

15

Cattle

✓✓

✓✓

✓✓

✓✓✓

9

2

Goat

(ibhokhwe)

✓

✓✓✓

✓✓✓

✓✓

9

7

Cabbage

✓✓(esp

July-Nov)

✓Needs lots of things,

expensive and needs a lot of

water

✓

✓✓

6

3

Potatoes

✓✓✓

✓Easy to grow- main cost is

labour in harvesting

✓✓

✓✓✓

9

26

Firewood

✓✓✓

✓✓✓

✓✓✓

✓✓✓

12

2

50

Thatching

grass

✓✓Supply

is limiting-

high local

demand

(disasters such

as fires, or

short grass can

b a big

problem)

✓✓No inputs costs, but

takes time to cut and prepare

✓✓

✓✓✓

9

4

50

Maize (dry

and green)

✓✓✓

✓

✓

✓✓People eat

a lot of maize;

local demand is

high

7

10

50

Wool

✓

✓✓sell without weighing,

classing or cleaning

✓✓✓

✓✓Under-

graded

sometimes in

Cedarville;

labour;

transport to Co-

op

8

5

5

The ranking achieved in the table above was discussed and changed to include an additional

criterion of number of people in the village involved in the enterprise and general demand in

the area. The commodities were thus ranked as follows:

1. Indigenous Chickens and commercial chickens (eggs and meat), 2. Potatoes,

3.Sheep (meat and wool), 4. Cattle and Goats and 5. Cabbage.

Rankings from other group discussions and villages were combined to form a more

generalised listing of important market or commodity chains for local marketing:

1. Poultry (meat and eggs), 2. Potatoes, 3. Sheep (meat and wool), 4. Livestock, 5.

Vegetable greens (imifino including turnips, spinach and cabbage) and 6. Maize

(included here as many smallholders grow maize, irrespective of profitability)

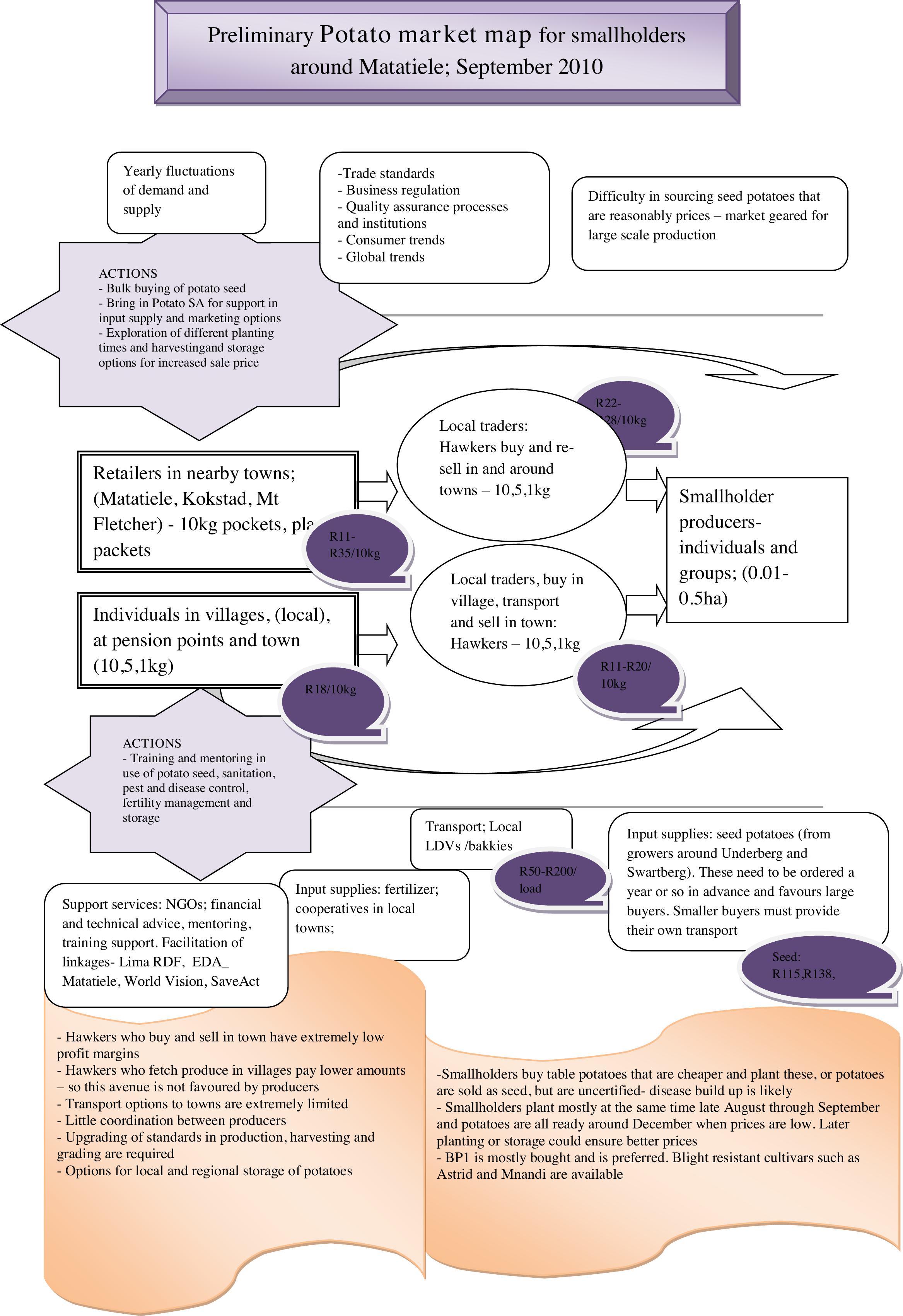

Market mapping: Market maps were produced for the 6 prioritized commodities (above),

after further interviews with stakeholders along the value chain in the region. Below, market

maps for poultry and potatoes are shown as examples.

The top 3rd of the map considers enabling business environment factors.

The middle 3rdof the map details market chain actors and their linkages. A ‘start’

insert summarises needed actions in this sphere.

The bottom 3rd of the map sets out business and extension service providers and a

‘start’ insert again summarises needed actions.

‘Flag’ inserts at the bottom of the page outlines key issues and constraints in the

market chain of this commodity.

ACTIONS

- Technical and management training

- SCG support in input supply and

marketing

- Strategic supply and marketing

arrangements facilitated through

membership organisations such as SA

Poultry

ACTIONS

- Bulk buying of feed.

- Better distribution network for

day old chicks

- Chicken abattoir

- Production and sale of 2 week

old chicks locally

Smallholder producers-

individuals and groups

- broilers and

layers(supported by

organisations – DSD,

World Vision, Lima,

DoA.......

Individuals in villages, (local), at

pension points and town buy eggs

and live chickens

Local traders: Hawkers

(buy and resell in and

around towns

Large hatcheries: National

Chicks and Stonor in KZN

Day old chicks –

R450-R490/box of

100

Point of lay hens:

R70-75/Hen

Feed: – large feed producers (Kokstad,

PMB),

- Cooperatives and retailers (bagged feed)

- Retailers – small quantities of bagged

feed, sometimes delivered

(Generally 60% more than bulk)

Smaller businesses; Distribution

e.g. Express Poultry. Small

hatchery in Swartberg.

Production: Laying hens,

multipurpose breeds

- Smaller numbers of laying hens not delivered – sources far

- Day old chicks are often very weak by the time they finally reach

smallholder farmers

- Bagging of feed through co-ops and then supplythrough retailers

makes it very expensive

-Large interest in poultry production, but groups not supported by

institutions often do not have the know how

- Inefficiencies in management, combined with high input costs

preclude a profit in many cases

Finisher: R240/50kg + R20/bag

transport

Laying mash: R190-R200/50kg

bag/ Transport: R80.00/5 bags

Live weight R60-

F80/chicken

Eggs R30/ tray 2.5

dozen or

R10.80/dozen

- Involvement of smallholders in commercial value chain

limited due to issues of scale, registration and economic

efficiency

-Local market opportunities are generally good.

- Potential for small speciality concerns that deal with 2

week old chicks, spent hens ....

SA Poultry; support for

smallholders – national sanitation,

disease monitoring, marketing,

supply chain management , policy

and global + local trends etc

Preliminary Poultry market map for smallholders

around Matatiele; September 2010

Requirements around slaughtering of

poultry preclude smallholders from

this market. No local poultry abattoir

Introduction of hardy multi-purpose

breeds and indigenous chickens

becoming more popular among service

providers

Other supplies; equipment,

medicines – are available through

cooperatives but generally

considered too expensive and are not

extensively used.

Information, mentoring and training;

organisations are present that can

support. Most smallholders work

withvery limited knowledge and

need a lot ofsupport

Local retailers e.g. Boxer

buy eggs. Also schools and

other institutions

Live weight R60-

F80/chicken

Eggs R27/ tray of

30

Spent laying

hens sold at

R30 ea.

R22-R28/10kg

ACTIONS

- Training and mentoring in

use of potato seed, sanitation,

pest and disease control,

fertility management and

storage

ACTIONS

- Bulk buying of potato seed

- Bring in Potato SA for support in

input supply and marketing options

- Exploration of different planting

times and harvestingand storage

options for increased sale price

Smallholder

producers-

individuals and

groups; (0.01-

0.5ha)

Individuals in villages, (local),

at pension points and town

(10,5,1kg)

Retailers in nearby towns;

(Matatiele, Kokstad, Mt

Fletcher) - 10kg pockets, plastic

packets

Input supplies: seed potatoes (from

growers around Underberg and

Swartberg). These need to be ordered a

year or so in advance and favours large

buyers. Smaller buyers must provide

their own transport

Seed:

R115,R138,

R160/25kg

Input supplies: fertilizer;

cooperatives in local

towns;

Transport; Local

LDVs /bakkies

-Smallholders buy table potatoes that are cheaper and plant these, or potatoes

are sold as seed, but are uncertified- disease build up is likely

- Smallholders plant mostly at the same time late August through September

and potatoes are all ready around December when prices are low. Later

planting or storage could ensure better prices

- BP1 is mostly bought and is preferred. Blight resistant cultivars such as

Astrid and Mnandi are available

R50-R200/

load

Local traders, buy in

village, transport

and sell in town:

Hawkers – 10,5,1kg

R11-R20/

10kg

- Hawkers who buy and sell in town have extremely low

profit margins

- Hawkers who fetch produce in villages pay lower amounts

– so this avenue is not favoured by producers

- Transport options to towns are extremely limited

- Little coordination between producers

- Upgrading of standards in production, harvesting and

grading are required

- Options for local and regional storage of potatoes

Yearly fluctuations

of demand and

supply

Difficulty in sourcing seed potatoes that

are reasonably prices – market geared for

large scale production

-Trade standards

- Business regulation

- Quality assurance processes

and institutions

- Consumer trends

- Global trends

R22-

R28/10kg

R22-

R28/10kg

Local traders:

Hawkers buy and re-

sell in and around

towns – 10,5,1kg

R11-

R35/10kg

R18/10kg

Support services: NGOs; financial

and technical advice, mentoring,

training support. Facilitation of

linkages- Lima RDF, EDA_

Matatiele, World Vision, SaveAct

Preliminary Potato market map for smallholders

around Matatiele; September 2010

3.3 Participatory value chain analysis

A value chain analysis was done for each commodity, with the intention of deepening

understanding, providing some input from the facilitators and building a stronger basis for

joint decision making around bulk buying for example. In this discussion, specific attention

was given to advice, mentoring and training support required. Emphasis was given to what

individuals and group members could do for themselves, as opposed to waiting for funding

and government support. Below is an example of a value chain analysis conducted and

summarised for two villages: Nkosana and Jabulani.

TABLE3:POUTLRYVALUECHAINANALYSIS

Poultry Value Chain for Nkosana and Jabulani

ACTIVITIES

COSTS ea activity

ISSUES

INFORMATION

REQUIRED

POSSIBLE

SOLUTIONS

Preparation of the

room where chicks

will be kept. The

floor is insulated

with soft grass or

sawdust.

Day old chicks: R5.00

at Matatiele. People

buy 20 - 100 chicks.

-20 chicks: R100.00

- 100 chicks: R500.00

Starter and Finisher

Mash:

5KG:R25.00 / R30.00

10KG:R50.00

50KG:R240.00

Transport: R15/bag in

the bus and R40/bag

in taxi

Two week old chicks:

R15-20.00

Feeds are very

expensive. There is

always risk of over-

feeding chickens

and they die as a

result.

Medication

Chicken growing

skills

Bulk buying of inputs

is very attractive and

can be done through

the SCGs- those in the

different groups that

are interested can

come together.

On arrival chicks

are given water

with medication.

Medication:

Teramicin (R20.00

per packet). The other

medication is Lasota.

Chicks and chicken

get sick very easily.

Common diseases

include worms,

influenza and sores.

Currently people use

care and traditional

herbs.

After two hours

chicks are fed with

Starter Mash.

Hardware/equipment:

R90.00 and R80.00

On week three the

chicks are given the

Finisher Mash.

Paraffin for lighting

On week five the

finisher Mash is

mixed with crushed

maize. This is done

to balance weight

and to make

chicken taste like

indigenous free

range chicken.

The addition of

crushed maize also

helps to make feed

cheaper.

On week six

chickens are given

both Finisher Mash

and raw maize.

They are ready for

the market /sale.

Most people

(farmers) feed

chickens beyond six

weeks mark. Local

customers buy on

credit. They are bad

payers. One can sell

between two and

Pricing

Establishing of

local markets.

Giving credit is one

strategy of avoiding

over-feeding chickens.

We can try joint

selling in SCGs, and

selling at pension

payout points.

three chickens per

month.

Those who have

deep-freezers are

able to slaughter

them and sell them

prepared.

SUPPORT NEEDED:

Access government subsidies (fencing and

other inputs)

Access to bigger loans and extended loan

terms (not the Women’s Development

Business, maybe UVIMBA and EC

Government Programme)

Facilitation of bulk buying (chicks and

feeds).

It became clear working in the villages with the SCGs that issues were broader and that work

would have to include different local SCGs. The idea for commodity interest groups

emanated from these discussions.

3.4 Commodity interest groups

Interest groups were set up in a number of the villages consisting of SCG members from

those areas. These groups considered the following potential actions:

oCollective or joint buying of input supplies coordinated across groups and villages

through a linkage person or organisation as a precursor to bulk buying.

oAdjusting the saving and pay-out processes in their group to accommodate

agricultural activities. It is possible to schedule annual share outs of capital to

coincide with the planting season.

oPrioritizing and coming together for learning events and information sessions.

oWorking together in groups or as groups of individuals to streamline agricultural

production and marketing.

Collective buying of inputs and learning and information events were prioritized. The

progress of group members were periodically tracked and monitored. A large public event in

the form of a Potato Information day was held in September 2010, where stakeholders such

as Potato SA, the Provincial Department of Agriculture, the local municipality’s Local

Economic Development section, NGOs such as World Vision and Lima RDF, community

members, commercial potato growers and commercial interests such as Sasol and Sanlam

were represented. From here a Potato Forum was formed to create the linkage for further

contact with Potato- SA and research and training possibilities, but mainly to coordinate bulk

buying activities for the NGOs and Department of Agriculture in the Matatiele area.

The potential of joint buying was illustrated by the order of vegetable seedlings and potato

seed that the Khaue and Jabulani villages asked SaveAct to place in 2011. This occurred even

though there had been no follow up in the communities since the previous initiative in 2010.

The seed potato order for 2012 has been substantial. In 2010 there were 15 x 30kg bags and

progressing to around 450 bags for the coming season. A summary of discussions with CIGs

around progress follows below:

1.In the first year people ordered on average 0.5 bags of potato seed each. These

potatoes did very well. They grew better and were bigger and healthier than before.

2.The advice regarding planting practises helped a lot as did the new variety of

potatoes, BP1.

3.Novuyani (from Khaue) said; “From 50kg of seed I made R2,500.00 selling the

potatoes. I charge R25/10kg bag .There was a great demand for the good quality

large potatoes and no one struggled to sell potatoes even though many of us had some

to sell.”

4.Groups chose prices that matched those in shops in Matatiele at the time. They felt it

was possible to add a little to that price as people do not need to go to town to buy;

5.Some of the potatoes were left in the field to harvest periodically over time. This is

the habit in the area. The potatoes grown from potato seed stayed fresh and

unblemished. “We cannot do this when we plant table potatoes as they rot in the

ground.”

6.Most members kept some for replanting, some for eating and some for selling.

7.In the following two years the members ordered and planted more seed; on average 1-

2 bags each.

8.They also mentioned that “It works well for us to coordinate our orders through

SaveAct. The Department of Agriculture is not reliable and it would be difficult to

work through them.”

Contribution of SCGs - It is understood that the SCGs assist members in term of savings

and loans for consumption and productive activities. The points below illustrate the nature of

the support from savings and credit using outcomes from the livelihoods assessment (Delany

and Storchi, 2012).

1.Members earn a significant income (2nd only to social grants) from their small

enterprise activities. See figure 2 below. The studywas conducted both in Matatiele

(n=60) in the Eastern Cape and in Bergville in KZN (n=74).

Earnings from Enterprise

Bergville

Matatiele

Last month1

R867 (range: R0 to R4 000)

R1 252 (range R0 to R10 000)

Good month2

R1 758 (range: R90 to R7 000)

R2 108 (range: R25 to R12 000)

Bad month3

R672 (range: R0 to R4 000)

R566 (range: R0 to R6500)

Figure 2: Earnings from small enterprises for SCGs members in the Eastern Cape and

KwaZulu-Natal

2.Members use loans from SCGs for starting and supporting their enterprise activities.

Figure 3a below indicates that 59% of respondents in Matatiele (n=147) used at least

one loan in the previous saving cycle for their enterprises (Delany and Storchi, 2012).

Overall around 9% of the money loaned has been used for agricultural enterprise development

in Matatiele, see Figure 3b.

1

Despite the recent time period, a number were not able to provide this information. No income estimates

were given or the SCG member did not know the amount in 23 of 94 cases in Bergville and 13 of 73 in

Matatiele.

2

No estimates were given in 19 of 94 cases in Bergville and 12 of 73 in Matatiele.

3

No estimates were given in 22 of 94 cases and 13 of 73 in Matatiele.

One respondent noted the following:“Members would borrow money to improve their

businesses and they know that they can borrow money from the group if anything in their

business is lacking…it is a two way process because [when]I have sold things, I take the

profit and save it to the saving scheme.”

Figure3a: Use of small loans from SCGs to support enterprise activities in Matatiele and

Bergville and Figure 3b: Overall use of loans for agricultural enterprises in Matatiele.

3.Loans taken in the SCGs are repaid primarily using income from grants (65%) and

from the small enterprises being undertaken (34%), as shown in Figure 4 below

(Delany and Storchi, 2012)

Figure 4: Sources of money for

repaying loans in the Matatiele SCG

membership.

4.Figure 5 below indicates the uses of share-out monies by SCG members in the

Matatiele area. These are lump sums that are available once a year. Around 7 % of

SCG members use their share out money for supporting their agricultural activities

(Delany and Storchi, 2012). Investment in inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, day old

chicks and chicken feed are common. Some members have fenced their fields, others

have bought tanks for water storage.

3% 4%

19%

37%

78%

59%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Bergville Matatiele

Used at least one

SCG loan to support

enterprise activities

Did not use an SCG

loan to support

enterprise activities

Not indicated

Non-

investment

, 30%

Household

, 35%

Enterprise,

5%

Agriculture

, 9%

Education,

21%

Investment

, 70%

Use of loans (Matatiele)

1%

10%

0%

1%

13%

2%

5%

26%

34%

65%

0%10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

Friends

Other relatives

Other external loan

Other SCG loan

Own savings

Another HH member

Employment

Spouse

Own enterprise

Grants

Matatiele (n=147)

Figure 5: Uses of yearly share out lump sums obtained through the SCGs in Matatiele

5.Levels of savings increase in the groups with length of membership, as shown in

Figure 6 below. Sources of money for saving are mainly grants. Income from

enterprises play a significant role as a source of money for savings and members saw

this as second only to grants. 41% of respondents mentioned using income from

enterprises as a source of savings (Delany and Storchi, 2012).

Figure 6: Changes in levels of savings between the 2010 and 2011 yearly savings cycles in

SCGs in the Matatiele area, compared with Bergville

Changes in SCGs

Some strategies for increasing productive activities may include changes in the focus and

management of the SCGs. Ideas that have developed internally have included:

1.Setting dates for monthly meetings to coincide with grant payouts; this is commonly

done.

2.Setting share out dates in October to coincide with need to buy agricultural inputs

3.Setting up SCGs specifically for the purpose of savings for agricultural inputs

4.Having membership in more than one group and having a slightly different focus for

savings and loans in each for these groups. From Figure 7 below it can be seen that

around 74% of members belong to one group only, 12% belong to 2 groups, 4 %

belong to 3 groups and 15 respectively belong to 4 -6 groups.

2%

3%

3%

3%

4%

7%

7%

7%

8%

9% 20%

20% 29% 58%

0%10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

Medical expenses

Other

Social or cultural purposes

Hired labour

Saved

Bought clothes

Bought food or groceries

Matatiele (N=147)

63%

18% 19%

89%

5% 6%

0%

50%

100%

IncreasedSame Decreased

Trend in Level of Savings

Bergville (n=62)Matatiele (n=62)

Figure 7: Membership of multiple SCGs among respondents in Matatiele

5.Planning joint marketing processes through the SCGs; such as selling produce at the

monthly meetings or jointly hiring transport for input supply or produce.

6.Working with SCG members as a specific client grouping for marketing particular

products.

7.Setting up small enterprises within the SCG membership that will support the

enterprises of the other members. An example here is to set up one member to rear

day old broiler chicks to two weeks of age and then sell them on to other members

who do broiler production and sale.

8.Buying and managing agricultural infrastructure together. One group has been

thinking of buying a second hand tractor together from their share-out payment and

then to hire this tractor from their group and also hire it out to other individuals.

SUMMARY

Members of savings and credit groups in Matatiele follow a stepped process of consumption

smoothing and investment in household and education needs before moving into investment

into small enterprises. Both loans and yearly share-out amounts are invested in enterprises,

mainly in the form of inputs. Income from the enterprises are ploughed back into the groups

in the form of savings. These groups are sustainable, offering unique access to financial

services to people living even in the most remote rural villages. This is having a powerful

influence on their motivation and capacity to engage in enterprise development and

agriculture.

The initial impetus for the formation of CIGs was the facilitation of a participatory value

chain analysis facilitated by SaveAct. This process of enquiry into local economic

opportunities and constraints inspired participants to form these interest groups to work

together to secure cheaper inputs and consider other strategies to strengthen their value

chains. These groups have formed a platform for collective action and innovation that have

included cooperation in productive and marketing activities, as well as input supply and

transport arrangements.

Furthermore, partnership with other organisations working in these areas that have more of an

agricultural focus has enabled members to access further agricultural training and mentoring

support.

9%

74%

12% 4%

1%

1%

Matatiele

Not indicated

1 group

2 groups

3 groups

4 groups

6 groups

SCG members indicated that one of the benefits of being part of an SCG is the support that

they receive from other group members. This helps them to become more confident in

starting or running an enterprise because they are able to share their problems and

knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SaveAct wishes to acknowledge the Vesper Society of California, USA for the funding for

the PMSA study. The wider LEAP programme also receives funding from the European

Union through Thina Sinako, a programme of the Eastern Cape Government and from the

National Development Agency.

SaveAct also wishes to acknowledge the FinMark Trust for financial support to conduct the

livelihoods assessment and small enterprise development study conducted in the Eastern

Cape and KZN.

REFERENCES

ALBU, M. and GRIFFITH, A. June 2006. Mapping the market: participatory market chain

development in practice. Small Enterprise Development. Vol.17 No 2.

ALMOND, F. and Hainsworth, S. (editors) (2005) Beyond Agriculture – making markets

work for the poor. Proceedings of an international seminar, CPHP, March 2005, London, UK.

BENNET, B. October2002. Market Scoping: methods to help people understand their

marketing environment. PLA Notes 45. Reading no 15.

Camp, K.T.G. 1999. Guide to the use of the Bio resource Programme. Cedara Report No

N/A/99/1. KZN Department of Agriculture.

Delany, A and Storchi, S. 2012. SaveAct Savings and Credit Groups and Small Enterprise

Development: Understanding Strategies and Opportunities to Promote Livelihoods Strategies

and Small Enterprise Development, including in Agriculture, through Savings Groups in a

Rural Setting. A Report for FinMark Trust, SaveAct.

Griffith, A. and Osorio,L.E. September 2008. Participatory market system development: Best

practices in implementation of value chain development programs.. USAID. Best practice in

implementation paper series. microREPORT#149.

McCleod, N: 2010 SaveAct/LEAP agro-project development support. Environmental and

spatial pointers for land based production initiatives for SCGS in the Matatiele area.

Environmental and Rural Solutions cc. PO Box 14 Matatiele.

PMCA user guide. Available from http://www.cipotato.org/pmca/11phase1.htm (Accessed

25 May 2010).

PRACTICAL ACTION. 2008. Mapping the market: A framework for rural enterprise

development policy and practice. Available from http://practicalaction.org/markets-and-

livelihoods/mapping_the_market (Accessed 25 May 2010).

Whitwell, P and Mitchell, F. 2010. Bio resource Programme: A natural resources

classification system for KwaZulu-Natal. Version 9 – printed 29/06/2010.

Wright,J. and Ng’habi,S. November 2009. Participatory Market Analysis. Hillside

Conservation Agriculture for Smallholder Farmer Livelihood Improvement Project (HICAP)

Conservation Agriculture Project, South Uluguru, Morogoro. CARE.