Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems

Volume 2: Resource Material

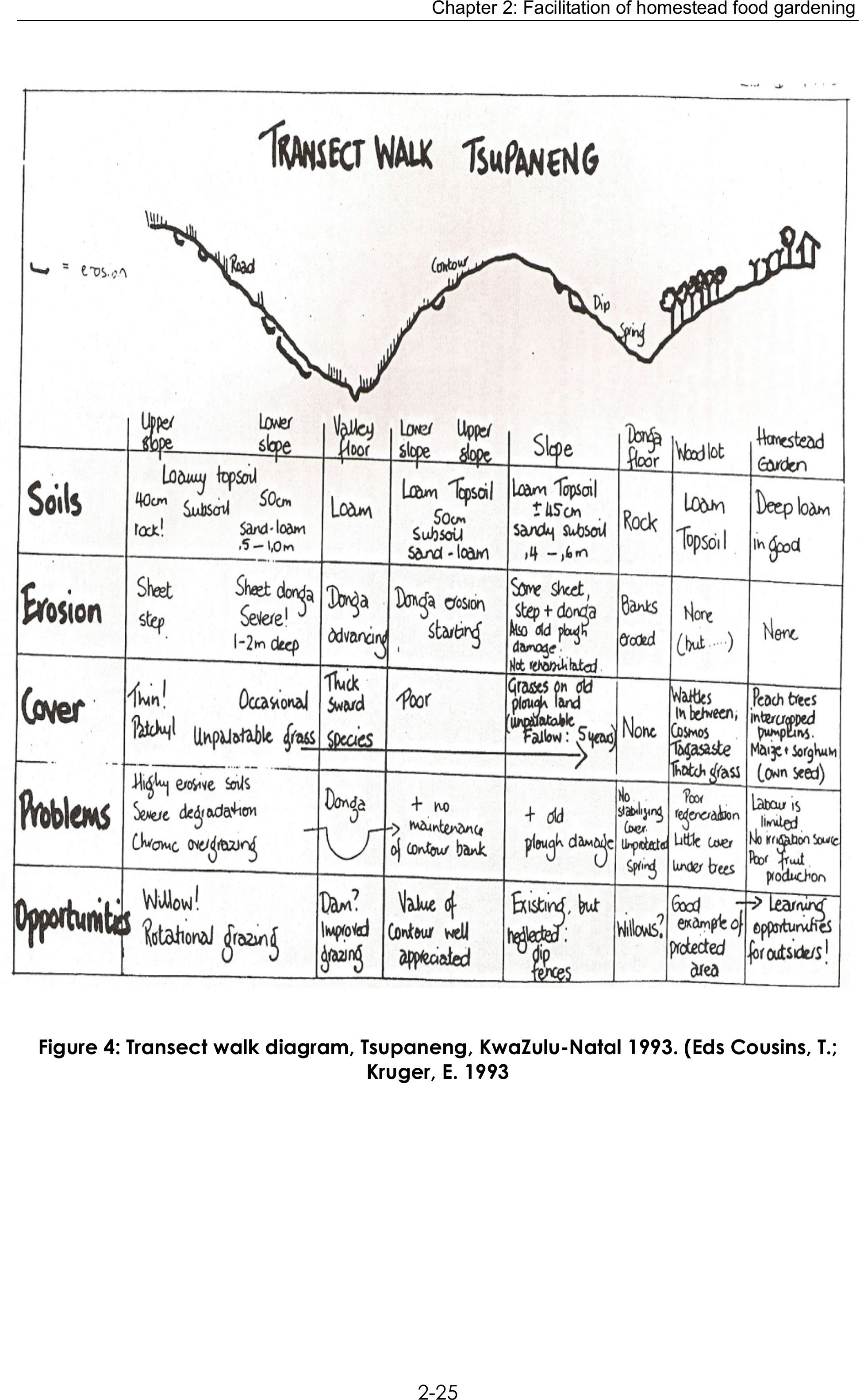

for Facilitators and Food Gardeners

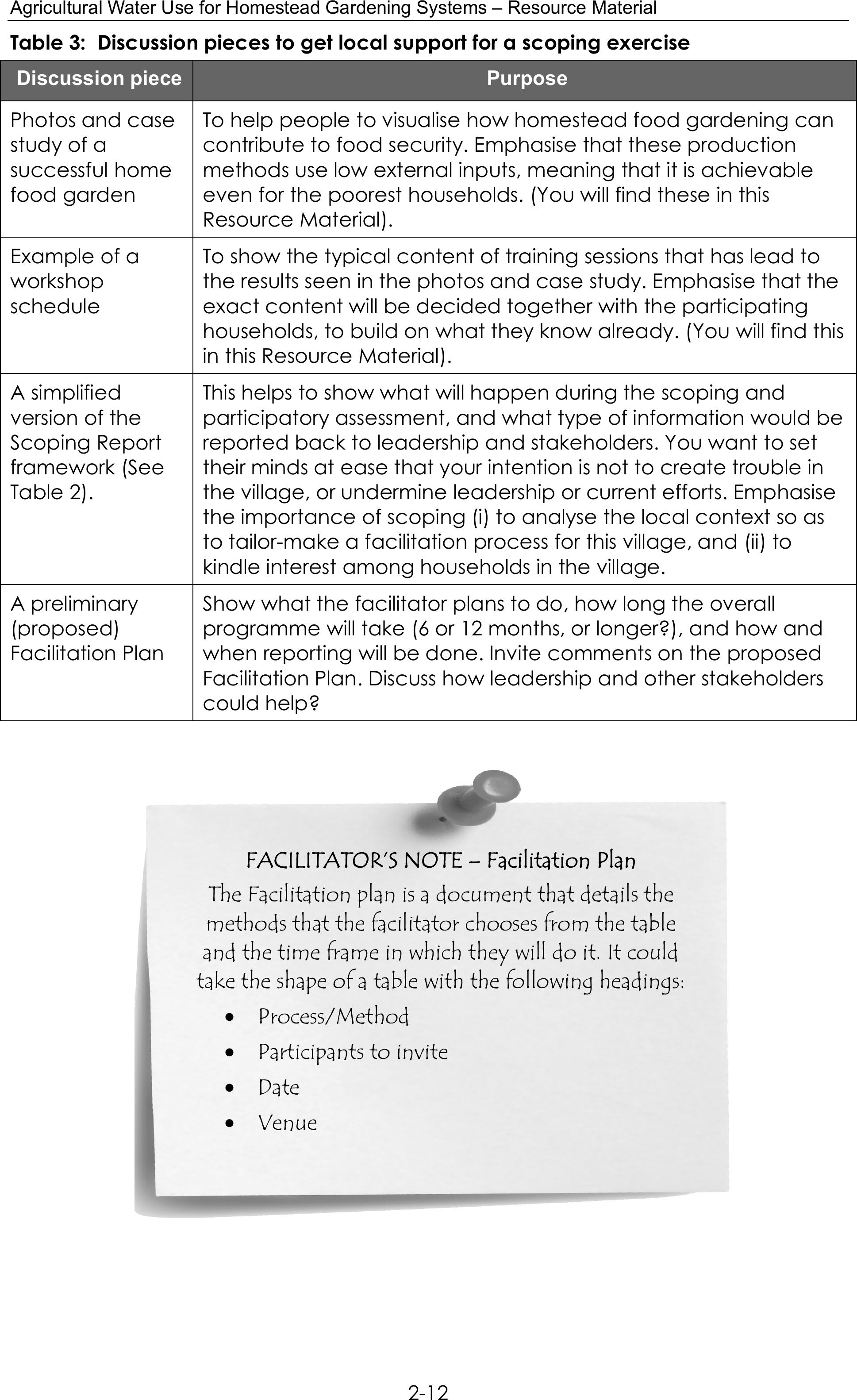

Part 1:

Introduction, Chapters 1-3

Report to the

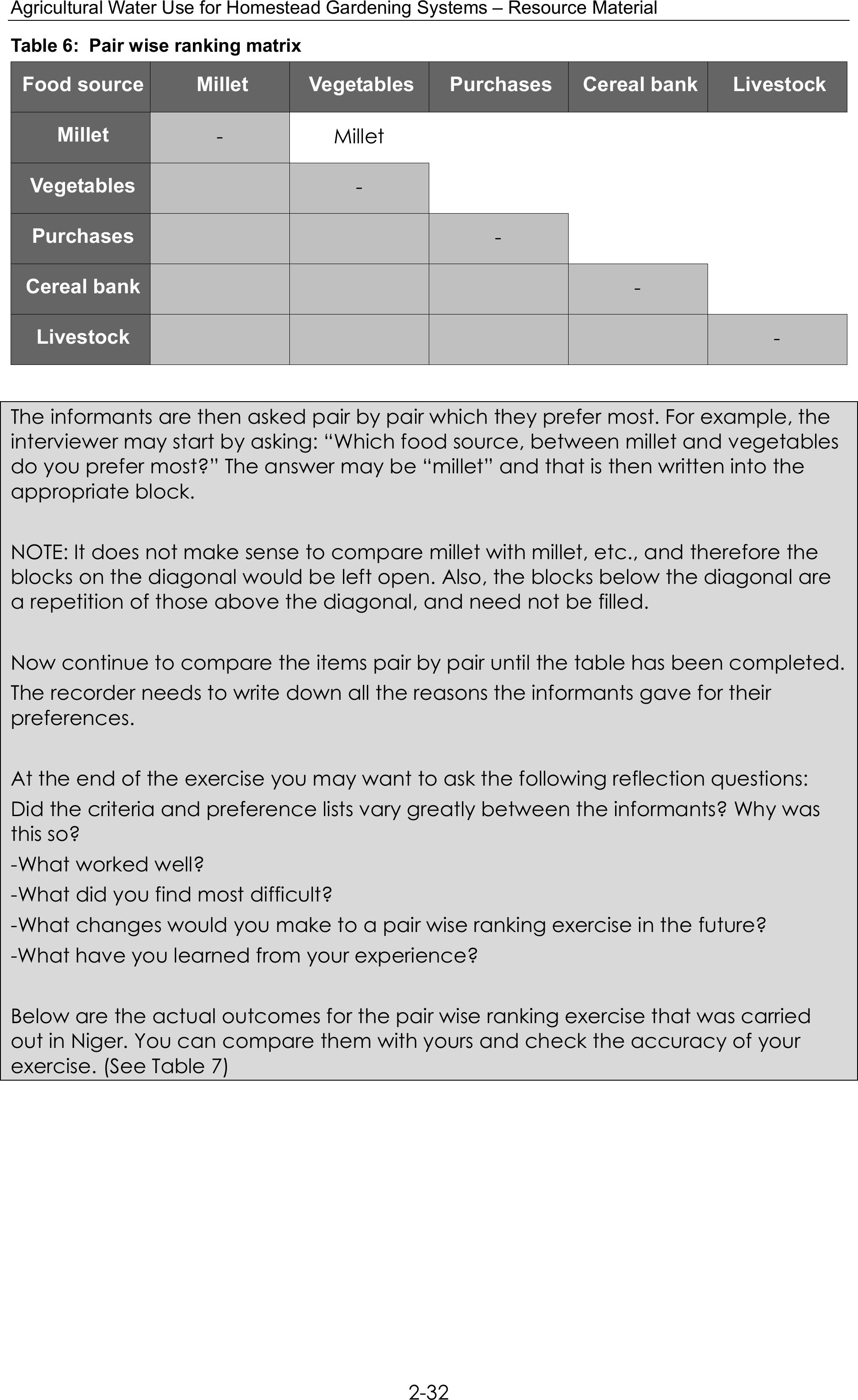

Water Research Commission

by

CM Stimie, E Kruger, M de Lange & CT Crosby

WRC Report No. TT 431/1/09

January 2010

Obtainable from

Water Research Commission

Private Bag X03

Gezina 0031

The publication of this reportemanates from a project entitled: “Participatory

Development of Training Material for Agricultural Water Use in Homestead Farming

Systems for Improved Livelihoods” (WRC Project number K5/1575/4).

This report forms part of a series of reports. The other report is entitled “Agricultural

Water Use in Homestead Gardening Systems – Main Report” (WRC report no.

TT 430/09).

DISCLAIMER

This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and

approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily

reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or

commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

ISBN 978-1-77005-918-4

Set No. 978-1-77005-919-1

Printed in the Republic of South Africa

Acknowledgements

WRC Research Project Reference Group:

Sanewe, AJ (Dr) Chairman (Water Research Commission)

Backeberg, GR (Dr) Water Research Commission

Crosby, CT (Mr) Private Consultant

Dladla, WR (Mr) Zakhe Training Institute

Ferreira, F (Ms) UNISA

Gabriel, MJM (Ms) DoA: WUID

Van Averbeke, W (Prof) Tshwane University of Technology

Williams, JHL (Mr) Independent Consultant

Sally, H (Dr) International Water Management Institute

Moabelo, KE (Mr) Tompi Seleka Agricultural College

Mariga, IK (Prof) University of Limpopo

Monde, N (Dr) Human Sciences Research Council

Engelbrecht, J (Mr) Agriseta

WRC Research Project Team:

CM Stimie (Mr) Project Leader –Rural Integrated Engineering

M de Lange (Ms) Coordinator – Socio-Technical Interfacing

E Kruger (Ms) Principal Researcher – Mahlatini Organics

M Botha (Mr) Layout and Sketches – Tribal Zone

W van Averbeke (Prof)Urban agriculture –Tshwane University of

Technology

J van Heerden (Mr) Engineering – Rural Integrated Engineering

CT Crosby (Mr) Advisor – Private consultant

The dedication and passion of Erna Kruger, Marna de Lange and Charles Crosby for

this project and its outcomes are acknowledged with gratitude.

Special recognition and acknowledgements to:

LIRAPA– Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Nutrition and Home

Economics, Horticulture Division, PO Box 14915, Maseru 100, Lesotho.

Department of Crop Services, Horticulture Division, PO Box 7260, Maseru 100,

Lesotho

MaTshepo Kumbane and the Water for Food Movement

Collaborated with:

The Smallholder Systems Innovation (SSI) Programme from UKZN in Potshini,

The Farmer Support Group

School of Bio-resource Engineering, UKZN

Specific thanks to Michael Malinga and Monique Salomon (FSG), Prof

Graham Jewitt, Victor Kongo, Jody Sturdy (SSI).

DWAF pilot programme for Homestead Rainwater Harvesting

World Vision; Okahlamba Area Development Programme – specific thanks to

Jamie Wright and Monica Holtz

ARC (ISCW); Eco-Technologies Programme in Hlabisa – specific thanks to

Hendrik Smith and the local DAEA extension office

Pegasus, Mpumalanga

LIMA Rural Development Foundation – Eastern Cape

AWARD – Limpopo

Bush Resources – Bushbuckridge

Border Rural Committee – Eastern Cape.

Centre for Adult Education (UKZN) – specific thanks to Zamo Hlela and Kathy

Arbuckle.

Umbumbulu – thanks to the Ezemvelo Farmers Association and assistance by

Dr Albert Modi, Crop Science Department, UKZN

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems

Resource Material

for

Facilitators and Food Gardeners

Introduction to the

Resource Material

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

ii

iii

Chapters: Resource Material

Introduction to the Learning Material (TT 431/1/09)

Chapter 1 Rural realities and homestead food gardening options (TT 431/2/09)

Chapter 2 - Facilitation of homestead food gardening (TT 431/2/09)

- Handouts: Chapter 2 – Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

Chapter 3 - Living and eating well (TT 431/2/09)

- Handouts: Chapter 3 – Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

Chapter 4 - Diversifying production in homestead food gardening (TT 431/3/09)

- Handouts: Chapter 4 – Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

Chapter 5 - Garden and homestead water management for food gardening

(TT 431/3/09)

- Handouts: Chapter 5 – Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

Chapter 6 - Soil fertility management: Optimising the productivity of soil and water

(TT 431/4/09)

- Handouts: Chapter 6 – Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

Chapter 7 Income opportunities from homestead food gardening (TT 431/4/09)

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

iv

Introduction to the Resource Material

v

Table of Contents:

Introduction to the Resource Material

Table of Contents: Introduction to the Resource Material................................ v

List of Figures ........................................................................................................... vi

List of Tables ............................................................................................................ vi

List of Activities ........................................................................................................ vi

List of Case Studies & Research ............................................................................ vi

The use of icons in the material ........................................................................... vii

1

1.

.

I

In

nt

tr

ro

od

du

uc

ct

ti

io

on

n

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

1

1

Rationale for this work............................................................................................. 1

How this resource material responds to rural realities ....................................... 2

Objectives of the research.................................................................................... 4

Overall objective .................................................................................................... 4

Specific objectives ................................................................................................. 4

Deliverables through the research process ........................................................ 4

Products of this research process (available documents) ................................ 5

2

2.

.

G

Gu

ui

id

di

in

ng

g

P

Pr

ri

in

nc

ci

ip

pl

le

es

s

a

an

nd

d

O

Ov

ve

er

rv

vi

ie

ew

w

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

6

6

3

3.

.

P

Pr

ro

oj

je

ec

ct

t

p

pr

ro

oc

ce

es

ss

s:

:

D

De

ev

ve

el

lo

op

pi

in

ng

g

t

th

he

e

R

Re

es

so

ou

ur

rc

ce

e

M

Ma

at

te

er

ri

ia

al

l

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

8

8

4

4.

.

L

Le

es

ss

so

on

ns

s

l

le

ea

ar

rn

nt

t

a

an

nd

d

i

im

mp

pa

ac

ct

t

o

of

f

t

th

he

e

r

re

es

se

ea

ar

rc

ch

h

p

pr

ro

oc

ce

es

ss

s

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

9

9

Cyclic, interactive learning processes: Look, learn, do ..................................... 9

Sensible approach to training needs assessments ............................................ 9

Defining ‘most promising’ methods and technologies ................................... 11

Development and testing of the Resource Material ....................................... 12

Impact of the use of the material ...................................................................... 12

Stakeholder consultation ..................................................................................... 13

5

5.

.

P

Po

oi

in

nt

ts

s

o

of

f

d

de

ep

pa

ar

rt

tu

ur

re

e

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

1

15

5

Incentives for homestead farming ..................................................................... 15

Different incentives for different people ........................................................... 16

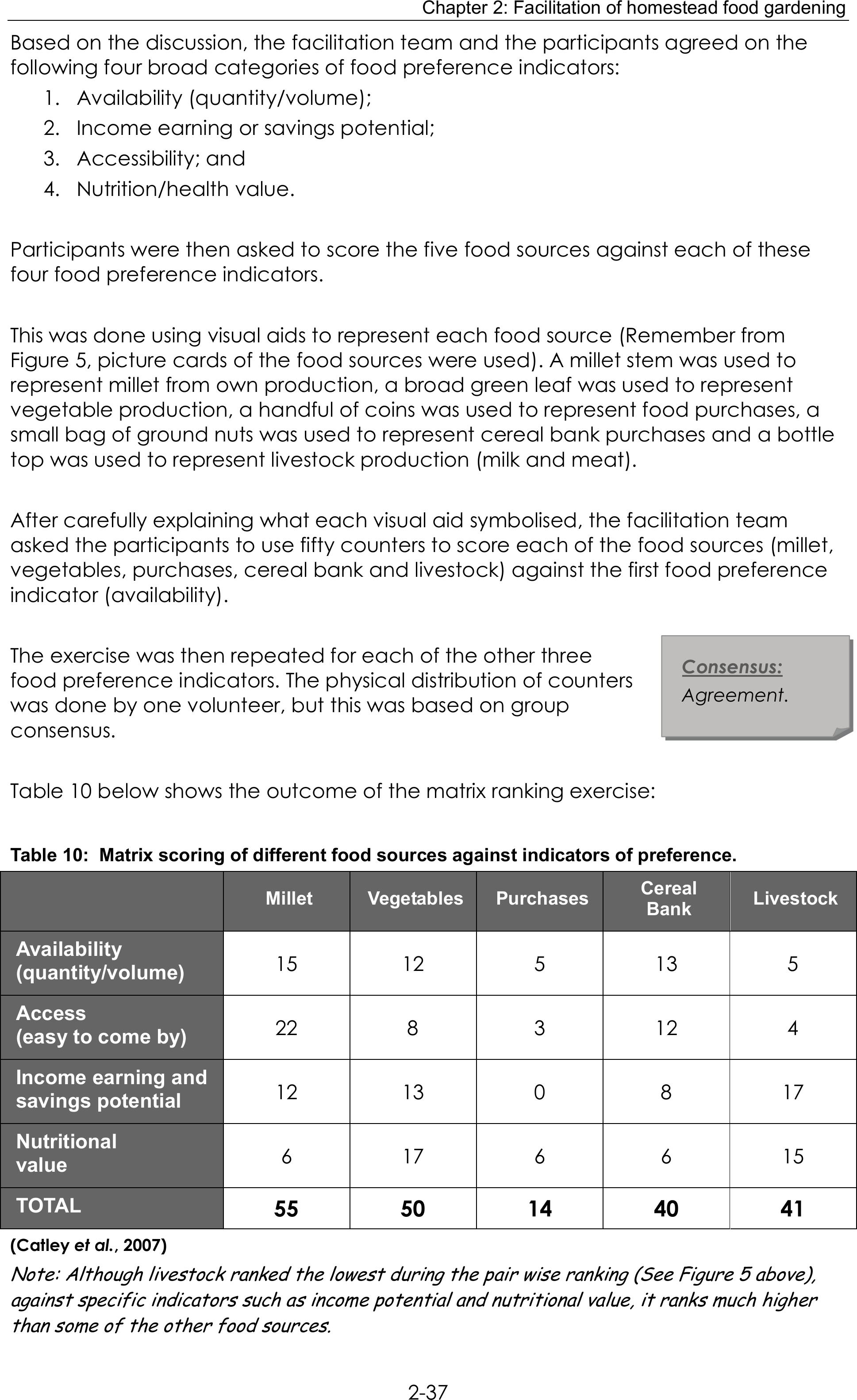

Tools to help us differentiate between incentives ............................................ 22

Get growing! Mobilising people into production ............................................. 32

Keep on growing your garden: Motivators and disruptors ............................. 35

Purpose and targeting of mobilisation .............................................................. 39

The ‘first brick’: Food security and resilience through diversification ............. 39

Spin-off benefits: Healthy eating for all .............................................................. 39

Second-phase: Income opportunities ............................................................... 40

Emotional healing as a foundation for food security ...................................... 41

Psychological effects of hunger ......................................................................... 41

Hunger as the ultimate symbol of powerlessness ............................................. 42

The need for harmonious and supportive relationships................................... 44

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

vi

The role of support groups in healing and overcoming powerlessness ........ 45

The role of joy, fun and laughter in healing ...................................................... 46

6

6.

.

R

Re

ef

fe

er

re

en

nc

ce

es

s

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

4

47

7

I

In

nd

de

ex

x

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

4

48

8

List of Figures

Figure 1: Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs................................................ 17

List of Tables

Table 1: Description of interactive learning processes used ........................... 9

Table 2: Alternative process for effective Training Needs Assessment ........ 10

Table 3: The ten human capabilities ................................................................. 20

Table 4: Linking household typologies to livelihoods and appropriate

interventions ........................................................................................................... 30

List of Activities

Activity 1: ‘Pull factors’ for homestead production ........................................ 21

Activity 2: Identifying incentives and disincentives within the different

household typologies............................................................................................ 31

Activity 3: The effects of hunger ....................................................................... 42

Activity 4: Universal feelings experienced by the hungry ............................ 44

List of Case Studies & Research

Case study 1: Ms Beauty Mbhele (Mantshalolo Village) ............................... 23

Case study 2: Mr Michel Mbhele (Kayeka Village) ........................................ 25

Case study 3: Mr Phelemon Mnguni (Ziqalabeni Village) ............................ 28

Introduction to the Resource Material

vii

The use of icons in the material

You will find that several different icons are used throughout the Learning Material.

These icons should assist you with navigation through the Chapter and orientation

within the material. This is what these icons mean:

Facilitation tools

Processes that you can use in workshop situations,

to support your work in the field.

Research /Case study

The results of research or case studies that

illustrate the ideas presented.

Looking at research, facts and figures

to help contextualise things.

Activity

This indicates an exercise that you should do

– either on your own (individual) or in a group.

Copy and handouts

These sections can be copied and used

as handouts to learners / participants.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

viii

Introduction to the Resource Material

1

1. Introduction

Rationale for this work

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition among development

practitioners in South Africa of the central importance of household food security.

Particularly, greater appreciation developed of the impact of food insecurity and

malnutrition – especially among preschoolers – on the individual, the family, and the

wider economy. Focus started to shift to the potential role of the homestead yard in

food production for improved family diets, and government started to realise that

lack of water had prevented many people from growing crops in their backyards.

This Resource Material for Facilitators and Food Gardeners on Agricultural Water

Management in Homestead Farming Systems was developed with funding by the

Water Research Commission (WRC) of South Africa, and is the output of a research

project entitled: “Participatory development of training material for agricultural

water use in homestead farming systems for improved livelihoods”.

The process of ‘participatory development’ of the material entailed two main

aspects:

Drawing widely on the material and know-how of practitioners in the fields of

household food security, homestead farming, farmer training, rainwater

harvesting and homestead water management, thereby achieving a collation of

existing expertise and material; and

Field testing and refinement of the collated material with food secure and

insecure households in rural villages.

The material built particularly on existing material of the Food and Agriculture

Organisation of the United Nations (FAO, 1997), the LIRAPA manual (Kruger, 2007)

and various South African resources. Through this WRC research project, it has been

integrated with the practical experience of practitioners and then field tested – in its

integrated form – for local circumstances.

The following aspects of the resource

materials can be viewed as innovations or

useful adaptations of existing practices:

Well-known Ma Tshepo Khumbane

devoted forty working years to

household food security facilitation,

and had countless successes in

mobilising households for food security.

One of the more difficult challenges for

facilitators who wanted to learn from

her, is to use her ‘present situation

analysis’ in the Mind Mobilisation

process, because this can be very traumatic for participants, and thus for

facilitators. (See Chapter 2 for more details). It is however, a very effective

mobilisation tool… A breakthrough came when the research team developed

the Nutrition Workshop as an alternative mobilisation tool to be used within the

This resource material is aimed at

facilitators and tutors-of-

facilitators in household food

security, homestead farming and

rainwater harvesting.

It also contains handout materials

for food

g

ardeners.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

2

overall Mind Mobilisation process. The Nutrition Workshop, measured effects of its

use, and later refinements of the process are described in Chapter 3.

This resource material draws, practically, on ways to understand and deal with

the psychological aspects that typically affect food insecure households. When

these are overcome, the journey to food security and wellbeing becomes much

more achievable.

The use of learning groups has been advocated and used with varying degrees

of success in agricultural development in recent years. Through this research, and

again, practical experience of a wide range of people, it was possible to better

define and refine the proper role for a ‘Garden Learning Group’ (or any other

name preferred by the particular group of households) to enable households to

support each other morally, while avoiding conflicts which most often stem from

some form of induced economic interdependence among group members.

In knowledge sharing with and among households, the successful use of

household experimentation as a learning process is well worth mentioning, and

discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

On the technical side, a significant range of technologies were selected and

field-tested, based on their affordability for cash-strapped households, and on

how they build up rather than break down the environment. Of particular interest

is the practical integration of a range of rainwater harvesting techniques with

organic plant production practices.

This Resource Material complements the Household Food Security Facilitators’ short

learning course at UNISA, as well as further courses planned by UNISA’s Human

Ecology Department that will draw on this material.

The University of KwaZulu-Natal was a valuable partner in the development of this

material and is presenting an elective on household water management as part of

its CEPD (Certificate in Education; Participatory Development) programme,within

the School of Education.

The Department of Agriculture requested the project team to develop specific

training courses as part of the implementation of the Agricultural Education and

Training, drawing on this resource material.

How this resource material responds to rural

realities

In the decade or so after the 1994 elections, agricultural extension and assistance

was targeted at group projects, rather than at individual or household initiatives. This

approach was adopted to enable government to reach more people

simultaneously, but has meant that assistance was not targeted at households who

wanted to develop independently, rather than being part of a group project

(communal garden, chicken project, irrigation scheme, land reform project, etc.)

Several shifts in thinking have since taken place, including the following:

An increased realisation of the reality of malnutrition and food insecurity in South

African households, exacerbated by the rapid food and fuel price increases in

2007/08;

Introduction to the Resource Material

3

Better understanding of the challenges

inherent in group-based projects –

especially the typical conflicts around

the handling of group finances;

An appreciation of the potential for

food production in the homestead

yards – a neglected tradition – and the

need for water to enable production at

the homesteads; and

Awareness of the potential of a range

of water access options, over and

above the conventional bulk supply and piped distribution systems; namely

‘multiple-use-systems (MUS)’, and especially rainwater harvesting in its various

forms.

The strategy of homestead production was voiced by poor people during the World

Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) hosted in Johannesburg in 2002. Food

insecure women from various provinces gathered at the World Summit and declared

‘War on Hunger’. Calling themselves the Water for Food Movement, they vowed to

do everything they could to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1a,

namely: “to reduce by half the number of people living with hunger, by 2015.”

To diplomats, ministers, and officials at the World Summit, they said: “We are the ones

going hungry, not you. Therefore we are the ones who must beat hunger and

achieve MDG1. Please don’t block us. If you can, walk next to us,but not in front of

us, dictating to us. We know our situation better than you do; this is our ‘war’.”

These women then returned home and showed practically at their homes what they

meant, by harvesting rainwater and digging underground rainwater tanks (or

‘dams’) to support their homestead production. Stemming from their demonstrated

success, the then Department of Water Affairs and Forestry approved a subsidy to

introduce rural households across the country to this type of low-cost, but intensive

home food production, and to finance the construction of homestead rainwater

dams to enable people to grow nutritious food at home – throughout the year.

The Water Research Commission (WRC) recognised homestead farming (and

especially food gardening) as poor households’ own self-identified coping strategy

to help protect themselves against the vulnerabilities of poverty. WRC then decided

to develop this resource material for facilitators on ‘Agricultural Water Management

in Homestead Farming Systems’ to help support poor households in their efforts to

grow food.

This resource material thus responds to people's initiatives, and is aimed at helping

households to grow more food at home, while using as little as possible of their

scarce cash resources.

It also provides some ideas for value-adding and marketing strategies to support

those households that decide to take their production to the next level.

(See Chapter 7: Income opportunities from homestead farming)

There developed a new focus on

the household itself – in its

existing context – and how they

could produce food (and possibly

a bit of income) in their own

homesteads, to improve their

f

oo

d

secu

r

ity

situati

o

n!

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

4

Objectives of the research

Overall objective

The overall objective of the research sets its focus clearly on home food security, and

practical testing of the learning materials, as follows:

The specific objectives, deliverables and products for the research were as follows:

Specific objectives

1.Identify current indigenous crop/livestock production practices.

2.Describe water related practices and efficiency of water use.

3.Identify developmental constraints on opportunities from natural resources,

infrastructure, human resources, HIV/AIDS, gender considerations, nutrition,

institutions and culture, for both rural and urban households.

4.Specify alternative and improved agricultural practices for use in

homestead gardens.

5.Determine economic incentives and entrepreneurial opportunities with

specific reference to the youth.

6.Identify value adding opportunities and appropriate marketing systems.

7.Determine training needs of household/home gardeners in relation to

available knowledge.

8.Develop and test training material to address needs.

9.Implement the training programme and interactively refine materials with

trainers and households.

10.Assess the impact of the project on food security of trained households.

Deliverables through the research process

1.Situation analysis report for South Africa.

2.Situation report for the selected target communities.

3.Report on how to use or to improve indigenous practices/systems, and on

possible alternative agricultural practices/systems for the selected areas.

4.Report on potential economic incentives and opportunities with specific

reference to the youth and value adding opportunities and appropriate

marketing systems.

5.Report on training needs of households/home gardeners in the selected

Improve food security through homestead food gardening,

by developing and evaluating the appropriateness and

acceptability of training material for water use

management, training the trainers and training household

members in selected areas.

Introduction to the Resource Material

5

areas in relation to most promising opportunities.

6.Proceedings of the first stakeholder workshop to obtain feedback from

stakeholders on the previous two reports.

7.Report on the refinement of practices and technologies after participatory

evaluation.

8.Progress reports on development and testing of training material.

9.Report on the effectiveness of the training methodology and

implementation

10.Proceedings of the second stakeholder workshop to obtain feedback from

stakeholders on the previous two reports.

11.Final training material.

12.Final report.

Products of this research process (available documents)

1.Situation analysis report for South Africa (Raise awareness of potential and

constraints of household agricultural production).

2.Situation analysis for selected target communities (selected areas report)

(Inform policy makers of the scope for and constraints on household

agricultural production).

3.Report on existing practices and technologies (Inform policy makers of the

scope for and constraints on household agricultural production).

4.Impact analysis of introduced technologies and training (Informing for

policy and budget considerations).

5.Training material (The Resource Materials for facilitators to implement

training).

6.Final report (Informing policy and implementation programmes).

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

6

2. Guiding Principles and Overview

The Chapters contained in this resource material follow a certain logic, based on key

questions the WRC research team had to ask itself.

On household mobilisation

Acknowledging that, while more and more households are starting home food

gardens, many others don’t believe it is possible or worthwhile, the research team

asked itself: “

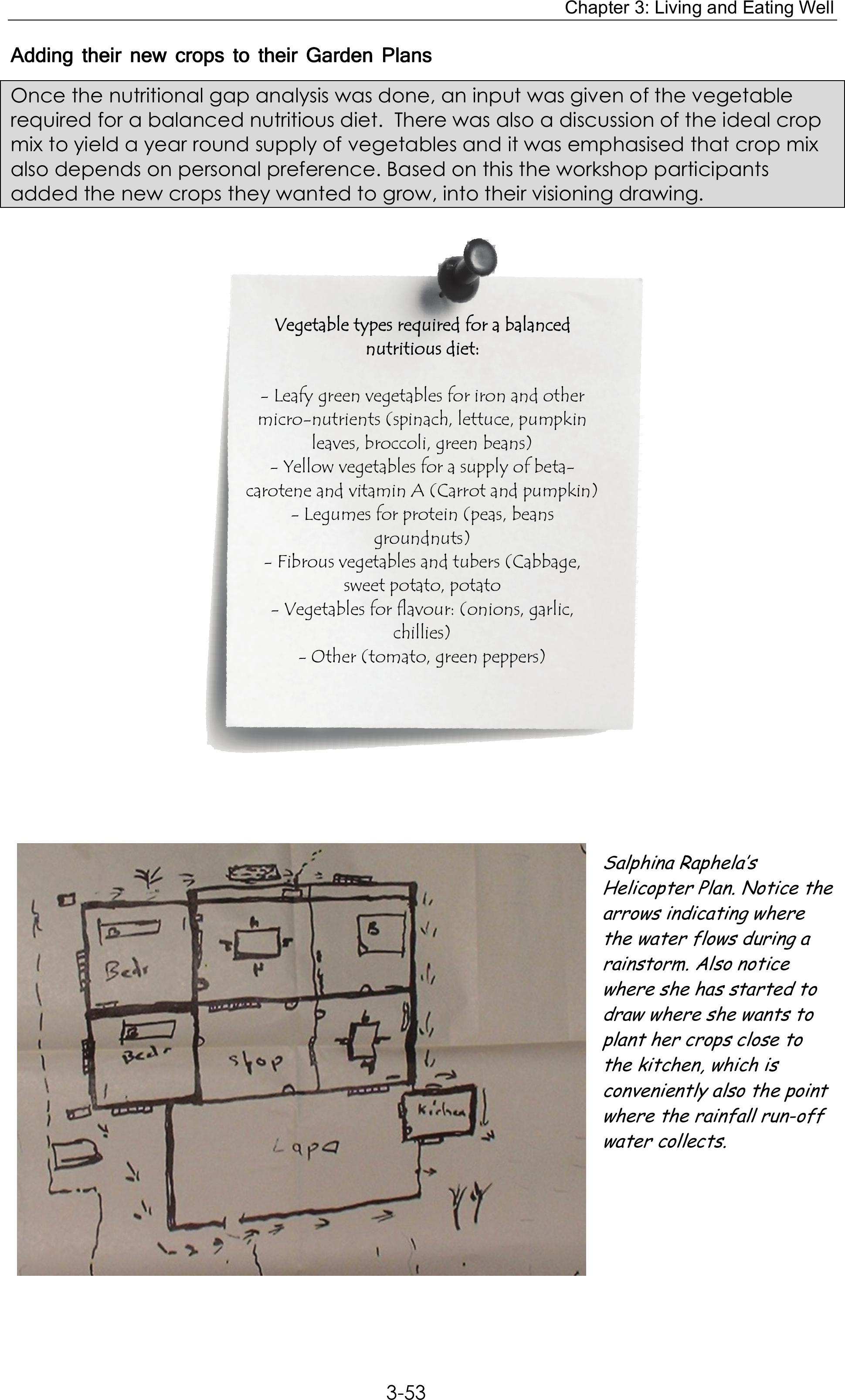

The research team developed and field tested the ‘nutrition workshop’, and found it

a very effective method to ‘create discomfort’ – which we know is where all

changes in habit springs from. The nutrition workshop enables the household to

analyse their own diets, discover the gaps, and choose crops to plant in their home

gardens to fill those gaps.

On ‘need-to-know’:

Deeply aware of the bewildering amount of information on organic production

methods, family nutrition, irrigation and water management, the researchers asked

themselves:

The topics of the chapters in this Facilitators’ Resource Materials manual stems from

that analysis, namely:

Chapter 1 Rural realities and homestead food gardening options

Chapter 2 Facilitation of homestead food gardening

Chapter 3 Living and eating well

Chapter 4 Diversifying production in homestead food gardening

Chapter 5 Garden and homestead water management for food gardening

Chapter 6 Soil fertility management: Optimising the productivity of soil and water

Chapter 7 Income opportunities from homestead food gardening

Handouts Homestead Food Gardener’s Resource Packs

“What is the minimum, essential knowledge a household

would need to successfully grow an intensive, worthwhile

home food garden? And then, what does the facilitator need

to understand to accompany these households on that

journey of discovery?”

How can the significance of

food gardening become a

reality in people’s minds?”

Introduction to the Resource Material

7

These chapters contain a lot more than the essential information. They enable a

facilitator to select what is appropriate to any specific garden learning group.

On cash-scarcity:

Recognising that these households are growing their own food precisely because

they have too little cash to buy enough nutritious food, the research team asked

itself:

Because of the reality of cash-scarcity, we believe the Low-External-Input Sustainable

Agriculture (LEISA) farming system (See Chapter 1: Rural realities and homestead

farming options) works best for homestead farming.

How can we select the

methods included in this

resource material to be

appropriate to the context

they will be used in?”

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

8

3. Project process:

Developing the Resource Material

The research process and the development of the resource materials can be

summarised as follows.

The Water Research Commission research team:

-Collated existing material;

-Consulted other practitioners in three different ways, namely:

One-on-one consultations;

Worked together in the field; and

Held two well-attended stakeholder workshops;

-Developed and implemented draft learning material with households in

several villages, with Potshini as the main site. In implementing the draft

learning material, the research team:

Worked through learning groups;

Emphasised follow-up home visits;

Emphasised learning processes that spanned at least one full growing

season, but preferably longer;

Used household experimentation as a learning tool;

Refined the mobilisation, facilitation and support processes; and

Refined the technologies with households, based on their experiences

with them;

-Wrote the required deliverables and built these into the Chapters of the

Resource Material where relevant. Of special significance were the following

deliverables (these are described in more detail in section 4 of this document

and in the Final Report: Participatory Development of Training Material for

Agricultural Water use in Homestead Farming Systems for Improved

Livelihoods):

An alternative approach to training needs assessment;

Refinement of practices and technologies after participatory

evaluation; and

Impact assessment on the effectiveness of the training methodology

and implementation of technologies;

-Tried several approaches for training and support of facilitators, and built

these lessons into the chapters of the resource material where relevant;

-Refined and finalised the Resource Materials; and

-Wrote a final report (WRC, 2009).

Introduction to the Resource Material

9

4. Lessons learnt and impact of the

research process

Herewith an overview of the key lessons learned and impacts achieved in this

research and implementation process.

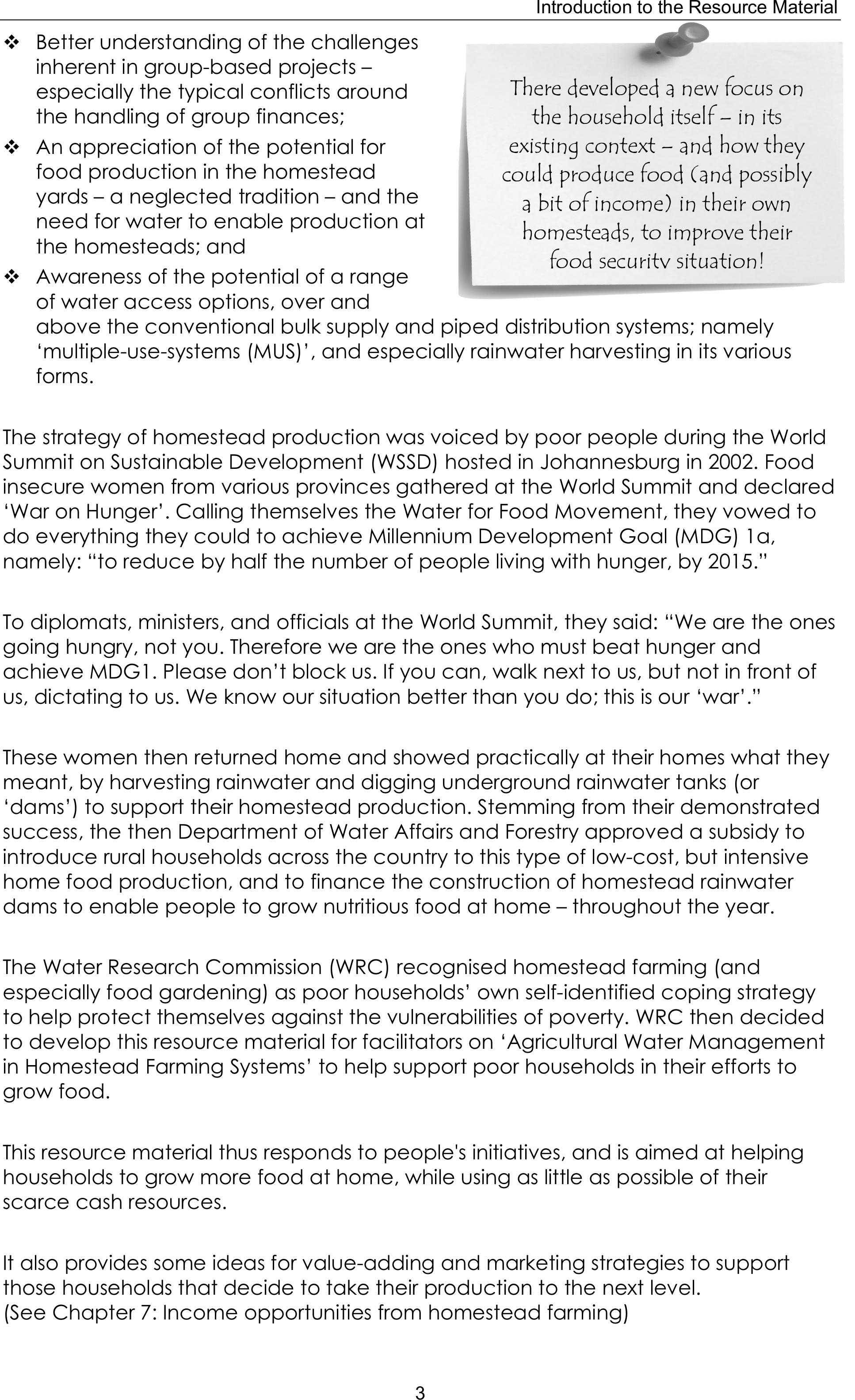

Cyclic, interactive learning processes: Look, learn, do

In the report on training needs assessment, the research team argued that cyclic,

interactive learning processes were most appropriate and effective in the

homestead food gardening context. Adults learn best:

from each other;

when there is an immediate need; and

in cyclic, practical processes.

Table 1: Description of interactive learning processes used

PROCESS ACTIVITIES METHODS/TOOLS

ASSESSMENTOBSERVATION

LAYOUT DRAWINGS

FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS

SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS

PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAL

ANALYSISLEARNING

ADULT EDUCATION

FARMER-TO-FARMER

LEARNING GROUPS

IN SITU ANALYSIS OF GARDENS

EXPERIMENTATION

- FOR PROBLEM

SOLVING

ACTION

FARMER EXPERIMENTATION

ACTIVITY CHARTS

DEMONSTRATIONS

EMPOWERMENT

-FOR OWN CHOICES

TO CHANGE

PLANNING

MINDMOBILIZATION

VISIONING

INDIVIDUAL RECORD-KEEPING

By using a greater variety of methods/tools, as shown in the table above,

opportunities for interactive, practical learning were maximised. In each cycle,

learning is reinforced and deepened.

Sensible approach to training needs assessments

Conventional training needs assessments attempt to produce a list of ‘training

needs’ for a geographical area. This inevitably results in a ‘shopping list’ of training

needs which may well be generally applicable, but almost certainly fail to fit the

specific training needs of any particular individual within that area.This results in

ineffective spending on ‘training needs assessments’, and subsequently less-than-

Examples

New ideas

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

10

ideal content of learning processes.

In contrast, we propose an alternative approach to training needs assessment for

homestead food gardening.

It starts with the generic (which is broad enough to cover the overall topic in

most contexts);

Followed by an approximate contextualisation (for instance,according to the

local natural resource base); and

Then eventually, specific training needs are defined only once the learning

group has been formed and prior learning of the participating households

established.

Table 2: Alternative process for effective Training Needs Assessment

GENERIC:

LEARNING

CONTENT

AREAS

The WRC Facilitators’ Resource Material contains a generic set of learning

content areas applicable to homestead agriculture. This is effectively

what is “on offer”, from which an applicable combination of material can

be extracted for any particular set of needs.

The WRC Research team collated this resource material through wide

consultation and in-field testing. Facilitators can further augment this from

other sources, should peculiar needs arise in a particular learning group.

SITUATION

ANALYSIS:

REVIEW

BROAD

CONTEXT

It is NOT necessary to perform a detailed training needs assessment at the

village or regional level

Establish whether there is an expressed need for household gardening,

and specifically for training in household gardening

Look at physical factors to see whether (and which of) the

recommended soil and water management practices would work in the

local context. Walk around the area and use external data sources to find

out more about the conditions for gardening in the area.

Find out what related processes have already taken place in the area.

Are people gardening? How well are they doing? Have they had training

before? What types of learning processes are preferred? Who is the

specific target group for further training interventions?

Establish whether there are any socio-political issues which may help or

hamper the implementation of a training programme in homestead

agriculture

SPECIFIC

TRAINING

NEEDS OF

HOUSEHOLD

LEARNING

GROUP:

“LEARNING

AND

ACTION

AGENDA”

Confirm that the members of the household learning group are clear

about what they want and can expect from participation in the

homestead food gardening training programme; their expressed training

need/learning agenda

Facilitate a group process through which members can express their

know-how in gardening. This provides a way to recognise prior learning

(RPL) in the group.

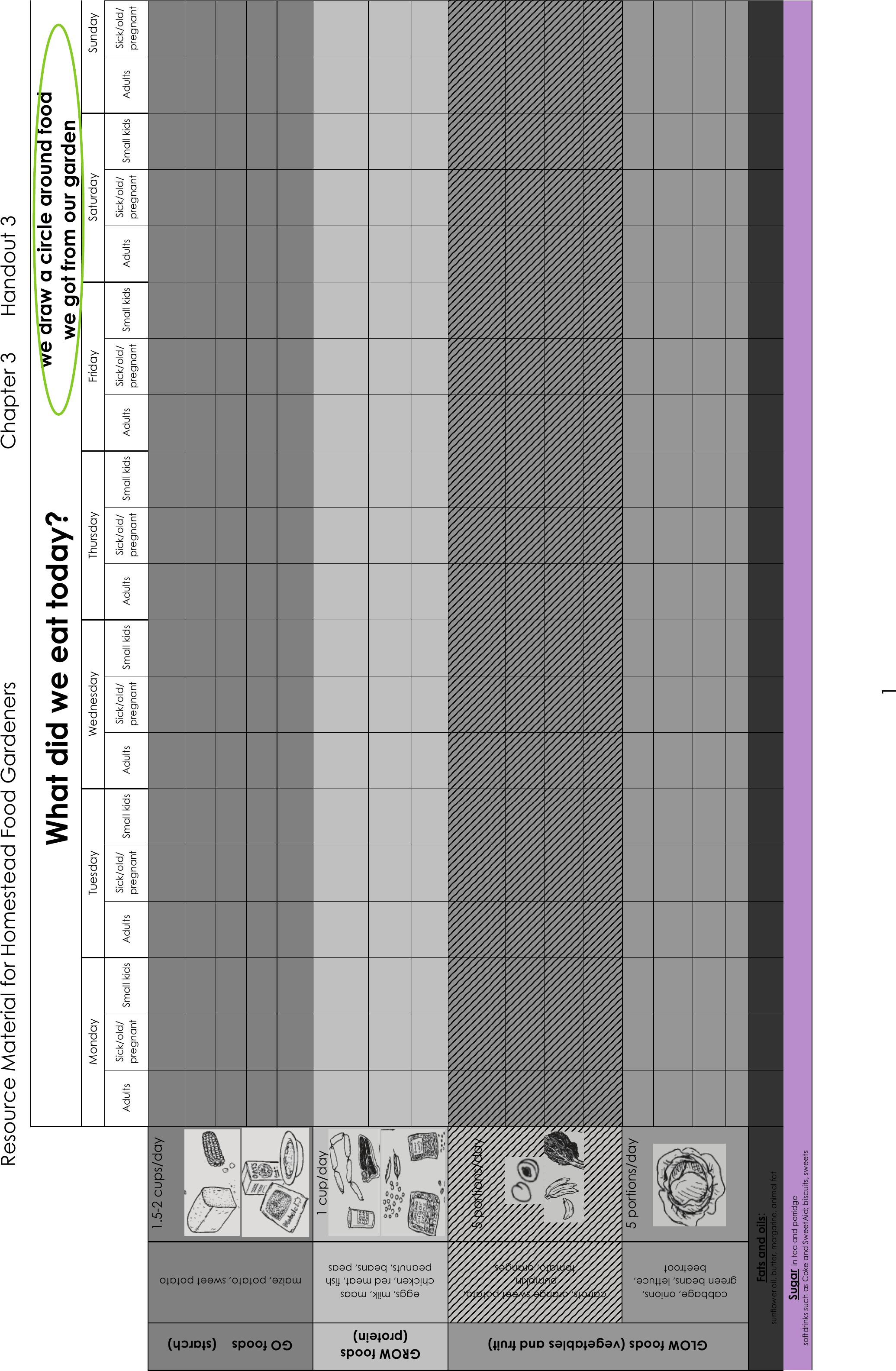

Facilitate a “nutrition gap analysis” with the learning group. The

households’ shortfalls in the “Go,Grow and Glow” food categories are

then used to plan their garden production and their “learning and action

agenda” for the current season.

Pick the actual training content from the WRC Facilitators’ Learning Toolkit

to suit theirlearning agenda.

Incorporate own experimentation throughout the learning plan.

Throughout the training programme, ask households about whether any

specific problems are arising and where appropriate and possible, adapt

the learning agenda to cover such issues.

Introduction to the Resource Material

11

Defining ‘most promising’ methods and technologies

After much debate, the team reached agreement on how to define the “most

promising” methods and technologies.

We believe this definition provides a handy way of identifying further “promising

technologies” in future. The most promising technologies identified to date include

LEISA, (See Chapter 1) deep trenching and tower gardens (See Chapter 4), the run-

on water system, home-based water storage, and treadle pumps (See Chapter 5).

Following practical implementation, experimentation and evaluation in the field, we

were able, in the “Report on the refinement of practices and technologies after

participatory evaluation”, to analyse each of the technologies that were introduced

at the hand of the following questions:

1.A description and/or analysis of the method/technology (What does it

entail?);

2.How the method differed from existing local practice (How is it different?);

3.How the method had been refined or adapted to improve it or make it more

suitable (How has it been refined?)

4.The outcome of assessments with households on how their performance

compared to existing local practice (Do people say it works better?); and

5.Measurements (where possible) of the performance of these methods and

technologies (How much better/worse?).

These questions provided a framework for systematic and comparative analysis and

reporting on the refinement of the technologies, as well as the effects of the

refinement. It provided a framework within which bothpeople’s opinion on the

usefulness of a technology, and available scientific work on the subject, could

contribute to the analysis. (For more detail on this, please see the Final Report.)

This set of questions also provides a mechanism for analysis and comparison of

further technologies as they become apparent in future. For instance, in field visits

subsequent to the completion of this report, we found it easier to assess the suitability

of the newly developed ‘pipe pump’ and the diaphragm pump, and a home-made

innovation for water-storage-and-irrigation which we discovered in one of the sites.

These methods and technologies have in common that

they help people get more for their effort in a cash

scarce situation.

These methods help people to intensify their

production thus getting better crop yield and quality,

while using low cost methods and locally available

inputs.

This im

p

roves efficienc

y

in the use of resources.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

12

The method of analysis also helped highlight for us where we may not have been

clear enough in our own thinking on certain aspects. For instance, it was somewhat

difficult to explain the run-on concept to households, and working through the

theory and practice of it amongst ourselves, we all gained new insights and felt we

would be better able to explain it to others in future (see the section on ‘Turning

runoff into run-on’ in Chapter 5).

It is a well-known phenomenon that tension almost invariably arises in

multidisciplinary teams, typically because of the difference in points of departure

and thinking processes employed by technically and socially oriented people,

respectively. We feel that the development of the Resource Materials benefited

greatly from constructive interdisciplinary analysis and interaction among members

of our team. Possibly, the way in which the questions lent equal weight to technical

and social matters, helped the interdisciplinary process of analysis.

Development and testing of the Resource Material

The research team used the following two questions in selecting the basic content of

the learning material contained here:

-For Households’ learning content: What is the essential knowledge a

household needs to grow food at home?

-For Facilitators’ learning content: What would a facilitator need to know and

be able to do, to teach or facilitate this content for food gardeners?

This approach provided sufficient structure and logic to plan the layout and content

of the learning modules for facilitators, as well as the handouts for food gardeners,

the latter which is included here in several languages.

The feedback received on the draft material, both during the second stakeholder

workshop and independently from other individuals, has been positive. There is great

interest in the utilisation of the material by several public and private training

institutions. The process of developing and testing the training material is discussed in

detail in the Final Report (WRC, 2009).

Impact of the use of the material

The report on the effectiveness of the training methodology and implementation

sought to answer two main questions:

1.To what extent have people taken up and implemented the new ideas brought

to them through the training?

2.How has the process used to introduce people to the new ideas affected the

uptake of the new ideas?

From surveys undertaken by the WRC team and others, it was clear that both the

uptake and continued use of the technologies at Potshini had surpassed

expectations. (See Final Report for details).

On the second question, the research team felt that our point of departure on

effective training methodology for the rural homestead context had been validated.

Introduction to the Resource Material

13

Our approach is described in significant detail in the Training Needs Report, and our

conclusions after evaluation are, in a nutshell:

-The use of Garden Learning Groups and learning through own household

experimentation is highly effective.

-The use of household self-analysis of nutrition gaps (the Nutrition Workshop) is

an important innovation as a ‘mind mobilisation’ tool to catapult households

into action, i.e. to start gardening to address their nutrition gaps. (The most

common nutrition gaps are protein and micronutrient deficiencies which are

easily available from fruit and vegetable production at home).

-Rushed training without follow-up is worth very little, and training and support

should be spread over at least one to three seasons to allow people to

experience the entire agricultural calendar – with the necessary support for

seasonal problems as they arise.

The process of analysis of the impact of training had a useful side-effect for the

research team. It sharpened our minds to the challenge of ‘training the trainers’

especially trainers for whom this would be a relatively new and unknown field of

practice. Again, rushed, quick-fix approaches to the preparation of facilitators

yielded disappointing results.

In contrast, the material was used very effectively (with merely some telephonic

input from the WRC team members) by an experienced facilitator with appropriate

agricultural background.

This led us to identify two complementary strategies for the development of skilled

Household Food Security (HFS) Facilitators, namely:

-Longer term, structured academic and practical education of HFS Facilitators;

and

-Transfer of the material and concepts to skilled agricultural facilitators, who

could in turn provide a ‘learning-by-doing’ opportunity for new facilitators by

training and mentoring them in real-life implementation situations.

Stakeholder consultation

In addition to one-on-one discussions with other practitioners and various

stakeholders throughout the research period, two stakeholder workshops were held.

The first stakeholder workshop was well attended by a good cross-section of

practitioners, researchers and officials. It was held in Bergville, and included a field

visit to Potshini village, where stakeholders could interact with households that had

been part of the research process, and could witness the results of the facilitation

and learning processes. For the research team, the main outcome of the first

stakeholder workshop was a strong recommendation by stakeholders that the

research output should NOT be a single ‘training course’ or ‘training material’.

Stakeholders argued that due to the range of situations found in practice, resource

material or a “facilitator’s resource pack” would be of greater benefit. This would

enable practitioners to select material from the resource material and tailor make

their own learning processes in response to every new situation they may encounter

over time.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

14

The Reference Group and the Water Research Commission accepted this change,

with the following consequence:

-The material in Chapters 1 to 7 was structured as resource material, rather

than a training course.

-The material was still structured along Outcomes Based Education principles,

using interactive layout, examples, case studies and activities for facilitators’

self-study.

-The material also contains structured facilitation tools which the facilitator can

use for interactions with target households in field situations.

-A set of handouts was added, namely the ‘Homestead Food Gardener’s

Resource Packs’, which contains material that facilitators may give to

participants in the facilitation processes that they undertake.

The second stakeholder workshop was not a large affair. Instead, the team aimed at

inviting skilled and knowledgeable individuals representing a cross-section of

fieldworkers, training and development practitioners and academics, who all have

an interest in the interface between household food security and homestead water

management.

The day was most valuable, with meaningful debate and concrete suggestions to

the WRC team towards the refinement of the material, its possible application

through various institutions and processes, and mechanisms for the future training

and establishment of Household Food Security facilitators.

Some of the key suggestions were to strengthen the Facilitators’ Resource Material as

much as possible with references to scientific work, where these were available; and

to seek opportunities to introduce and test the material in further test sites in follow-

up work to the current WRC project. This has been done, and references are

provided throughout Chapters of the Resource Material.

This material can be adapted for a variety of stakeholders to suit their needs. It can

also be augmented by developing material above and below NQF (National

Qualifications Framework) level 5.

Introduction to the Resource Material

15

5. Points of departure

Incentives for homestead farming

What motivates people to grow food at home, and particularly, to keep on doing it?

The possibility to save – and even earn – some money, is an obvious incentive to

engage in homestead farming, but is that all there is to it? Many never start, and

some start enthusiastically, but abandon the practice after some time. Households

who keep on growing their food gardens year after year, would appear to be those

who have succeeded in adopting it as a way of life – as part of their daily or weekly

routine, and as part of their planning for the season or the year.

A better understanding of the range of reasons that get people into home food

production, and of the motivating factors and processes that help people to stay

committed to this, should help to maximise the contribution of homestead farming to

the food security, healthy eating and even some income supplementation of

households in South Africa.

Key questions

1.What gets people into home food gardening and to keep on gardening

(incentives), and conversely, what keeps them from growing their own food or

stopping once they started (disincentives)? Are there proven ways to mobilise

more households into homestead farming and to avoid abandonment?

2.Can one use a variety of approaches to reach people who differ greatly in

their objectives and abilities?

3.How can food insecure people come to believe in themselves and their ability

to grow their own food with what they have?

4.How can one compensate for the inherent scarcity of cash in food insecure

households? Can one introduce production methods that reduce the cash

requirement for inputs?

5.How can people’s own seed storage and the revival of seed exchange

traditions help increase the diversity and robustness of local varieties over

time?

6.What is the role of local interest/learning groups in mutual encouragement

among gardening households? Can the collective memory for planting dates

and practices and the ‘annual planting calendar’ tradition be revived to

remind and encourage all households to start their preparations in time?

7.Is it achievable to save and even earn significant money from homestead

farming in South Africa? And are there opportunities for value-adding which

are achievable for resource-poor households?

8.Can one easily recognise and avoid seemingly attractive possibilities that

carry too much risk for already food insecure households?

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

16

Different incentives for different people

What people do, arise from what they think and believe. This is influenced by their

circumstances. People have different reasons for getting involved in homestead

farming.

For instance:

An established homestead farmer, like Mr Mapumulo in Umbumbulu, may be

thinking about planting out-of-season to capture lucrative markets;

A grandmother could be planning to plant a range of foodstuffs to be ready for

harvest during her children and grandchildren’s annual visit over Christmas;

A cash-strapped household may want to plant food to replace expenditure on

essential foodstuffs;

A concerned mother may wish to find an affordable way to increase the diversity

and attractiveness of family meals, and of having healthy snack foods for young

children; and

Some households may want to generate additional income by selling

vegetables, seed, adding value through preservation, packaging, etc.

The two ‘pull’ factors: Food and income

Professor Tushaar Shah (Shah, 2004) describes

what he calls ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors for

agricultural development.

All the factors of production are ‘push factors’.

These are the things that enable production,

such as land, inputs, machinery, credit, and

even institutional arrangements and training. Often, shortfalls in these ‘push factors’

are what government support programmes offer in an attempt to stimulate

development, or production.

However, Professor Shah states that:

A ‘pull factor’ is needed to stimulate people into production. The main pull factor is

the market, which makes it worth people’s while to produce. The more lucrative a

market is, the stronger the pull factor. Further, if people perceive that it is within their

ability to provide what the market wants, they will

go to great lengths themselves to find the means

(the ‘push factors’), in order to benefit from that

market.

Shah then quotes an example of what he calls

‘runaway’ or ‘wildfire development’ – in the ideal

case where the market wants – in significant

quantities and at a worthwhile price – something

which is very easy for a large number of poor

...push factors in themselves do

not lead to development

production.

An even stronger and

primary ‘pull factor’, of

course, is one’s

stomach

– both actual hunger

and the fear of hunger.

Introduction to the Resource Material

17

households to produce – and with means already at their disposal. In such a case,

almost everyone can respond very quickly to the ‘market pull’, and the need

disappears for government to try to ‘push’ development along. For instance, such

‘wildfire development’ happened in West Africa, when the demand and price for

local fish soared, and poor households could suddenly earn good income from an

established and well-known traditional practice.

An old Chinese proverb says: “A hungry man sees only one problem. Once the

hunger is satisfied, he sees many.”

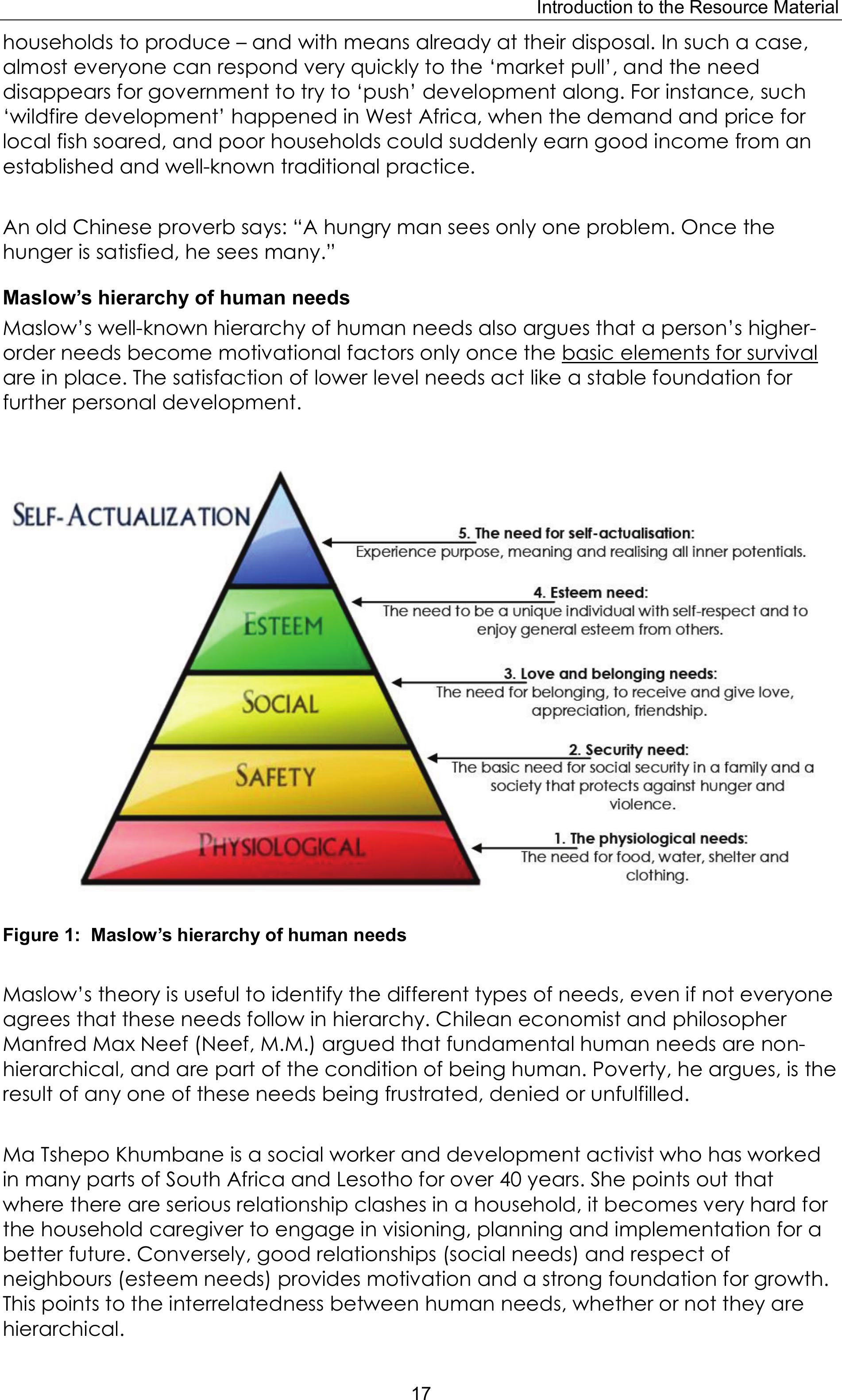

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

Maslow’s well-known hierarchy of human needs also argues that a person’s higher-

order needs become motivational factors only once the basic elements for survival

are in place. The satisfaction of lower level needs act like a stable foundation for

further personal development.

Figure 1: Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

Maslow’s theory is useful to identify the different types of needs, even if not everyone

agrees that these needs follow in hierarchy. Chilean economist and philosopher

Manfred Max Neef (Neef, M.M.) argued that fundamental human needs are non-

hierarchical, and are part of the condition of being human. Poverty, he argues, is the

result of any one of these needs being frustrated, denied or unfulfilled.

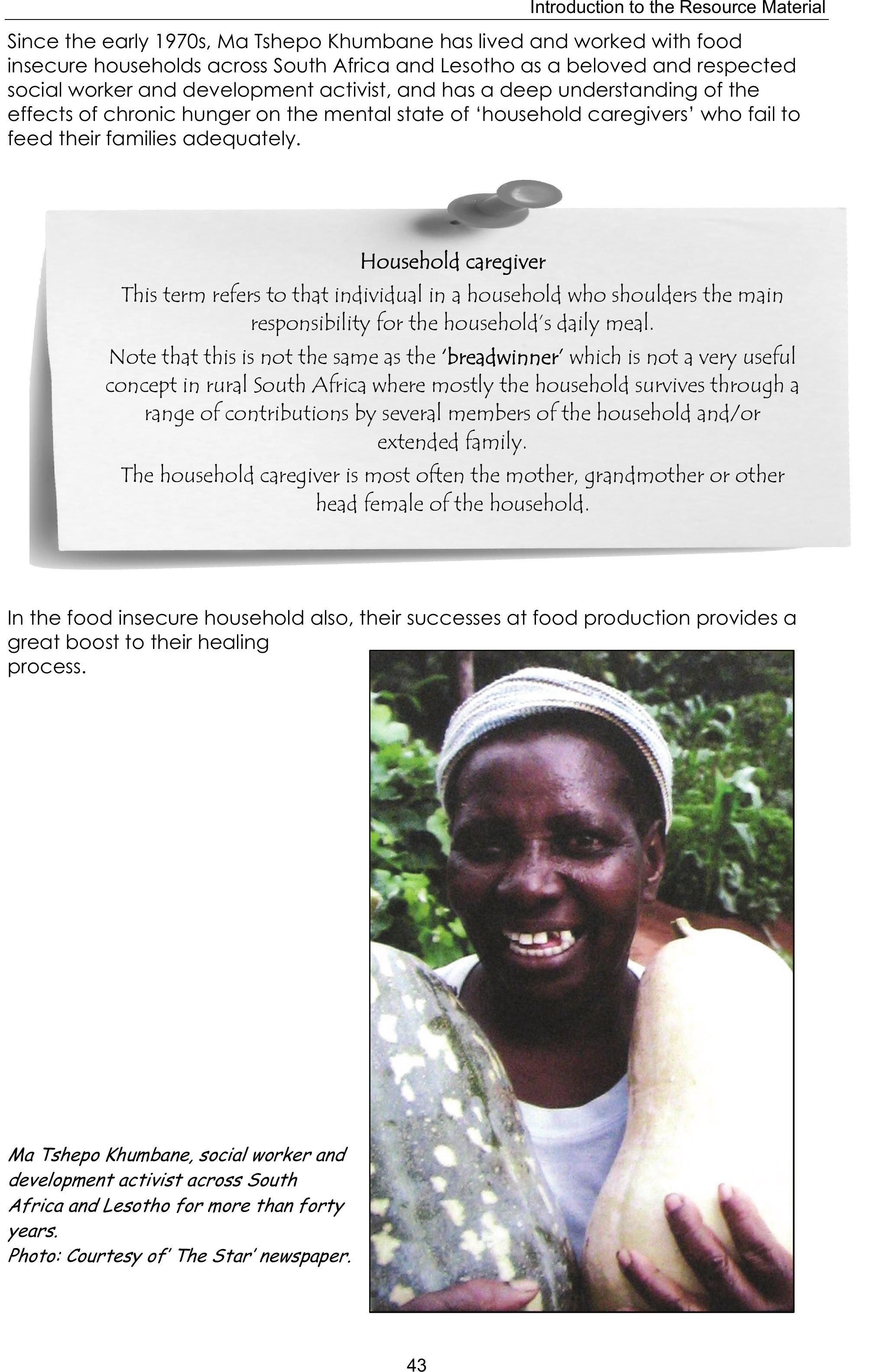

Ma Tshepo Khumbane is a social worker and development activist who has worked

in many parts of South Africa and Lesotho for over 40 years. She points out that

where there are serious relationship clashes in a household, it becomes very hard for

the household caregiver to engage in visioning, planning and implementation for a

better future. Conversely, good relationships (social needs) and respect of

neighbours (esteem needs) provides motivation and a strong foundation for growth.

This points to the interrelatedness between human needs, whether or not they are

hierarchical.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

18

An understanding of the interplay between human needs also goes a long way to

explain the role and usefulness of the Garden Learning Group approach to

facilitation. (See Chapter 2 for more detail).

It is interesting that in recent years, a sixth level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has

been proposed, namely ‘transcendence’, which is sometimes described as ‘helping

others to self-actualise’. This recognises the motivational value to oneself, of reaching

out to others. Participants in the Garden Learning Groups are encouraged to help

others around them, in spite of their own dire situation, because reaching out

actually helps their own healing process.

Understanding

Understanding the interrelatedness between

human needs helps a facilitator to become more

effective in motivating and mobilising

households, by:

Understanding why there might be a lack

of progress in a specific household;

Coming up with alternative mobilisation

and facilitation strategies to work

around such problems; and/or

Arranging for specific interventions or

assistance for a household to solve such

problems.

Introduction to the Resource Material

19

The Ten ‘Human Capabilities’

Martha Nussbaum (Nussbaum, 2007) takes the thinking about human needs further

with the ‘human capabilities’ theory, which shows the range of material and non-

material factors that enables a person to live a full life – in other words, a life where a

person can develop all ten their ‘human capabilities’.

Humans need to be all that they can be, by developing all ten of the human

capabilities (see Table 6 below). The capability approach contrasts with a common

view that sees ‘development’ purely in terms of Gross National Product (GNP)

growth, and ‘poverty’ purely as income-deprivation.

In this approach, poverty is understood as being not just income deprivation but also

encompassing capability-deprivation. It is noteworthy that the emphasis is not only

on how human beings actually function but on their having the capability, (which is

a practical choice), to function, (i.e. functional capability) in important ways if they

so wish. Someone could be deprived of such capabilities in many ways, e.g. by

ignorance, government oppression, lack of financial resources, or false

consciousness.

The approach emphasizes substantive freedoms, such as the ability to live to old

age, engage in economic transactions, or participate in political activities. These are

construed in terms of the substantive freedoms people have reason to value – such

as happiness, desire-fulfilment or choice – rather than mere access to utilities or

resources such as income, commodities and assets.

This understanding now underpins the Human Development Index and the Human

Development Report produced annually by the United Nations Development

Programme.

Personal responsibility, excellence and

faithfulness:

The ability to develop all the human

capabilities does not necessarily result

in them being developed. Personal

responsibility and faithfulness is also

necessary.

When everything is in place for

people to achieve something, they

can still choose whether or not to

try/persevere.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

20

Table 3: The ten human capabilities

“A list of specific capabilities as a benchmark for a minimally decent human life”

1. Life.

Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or

before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.

2. Bodily Health.

Being able to have good health, including reproductive health; to be adequately nourished;

to have adequate shelter.

3. Bodily Integrity.

Being able to move freely from place to place; to be secure against violent assault, including

sexual assault and domestic violence; having opportunities for sexual satisfaction and for

choice in matters of reproduction.

4. Senses, Imagination and Thought.

Being able to use the senses, to imagine, think,and to reason – and to do these things in a

“truly human” way, a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education, including,

but by no means limited to, literacy and basic mathematical and scientific training. Being

able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing works

and events of one’s own choice, religious, literary, musical, and so forth. Being able to use

one’s mind in ways protected by guarantees of freedom of expression with respect to both

political and artistic speech, and freedom of religious exercise. Being able to have

pleasurable experiences and to avoid non-beneficial pain.

5. Emotions.

Being able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves; to love those who

love and care for us, to grieve at their absence; in general, to love, to grieve, to experience

longing, gratitude, and justified anger. Not having one’s emotional development blighted by

fear and anxiety. (Supporting this capability means supporting forms of human association

that can be shown to be crucial in their development.)

6. Practical Reason.

Being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the

planning of one’s life (protection for the liberty of conscience and religious observance.)

7. Affiliation.

A. Being able to live with and toward others, to recognize and show concern for other human

beings, to engage in various forms of social interaction; to be able to imagine the situation of

another. (Protecting this capability means protecting institutions that constitute and nourish

such forms of affiliation, and also protecting the freedom of assembly and political speech.)

B. Having the social bases of self-respect and non-humiliation; being able to be treated as a

dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others. This entails provisions of non-

discrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, caste, religion, national

origin.

8. Other Species.

Being able to live with concern for and in relation to animals, plants, and the world of nature.

9. Play.

Being able to laugh, to play, to enjoy recreational activities.

10. Control over One’s Environment.

A. Political. Being able to participate effectively in political choices that govern one’s life;

having the right of political participation and protections of free speech and association.

B. Material. Being able to hold property (both land and movable goods), and having

property rights on an equal basis with others; having the right to seek employment on an

equal basis with others; having the freedom from unwarranted search and seizure. In work,

being able to work as a human being, exercising practical reason and entering into

meaningful relationships of mutual recognition with other workers.

Introduction to the Resource Material

21

Summary

The desire to fulfil a ‘human need’ or to develop a ‘human capability’ is what

motivates a person to do something. We need to understand these motivational

factors if we want to become more successful at:

Mobilising people into homestead farming; and

Motivating them to keep on producing year after year.

We also need to learn more about those things that discourage or demotivate

gardeners, and events that cause a break in production which could make it hard to

get back into production again. Following the old adage ‘prevention is better than

cure’, we can then try to help people avoid demotivating situations and events.

For the mobilisation of households into homestead farming, we can focus on two

‘pull factors’, namely food, and income.

Activity 1:

‘Pull factors’ for homestead production

Aim:

To identify the ‘pull factors’ for homestead production in a given situation, and

understand its role in mobilisation and in the sustainability of homestead farming.

Instructions:

1. Read through the situations described under ‘different incentives for different

people’ above. In each situation, try to identify whether food or income/money is

the incentive for production. Do you think this can change over time for a specific

household?

2. Now read though the ‘human capabilities’. Which of these ten

‘needs/capabilities’ could possibly also provide incentives for home food

production? For each ‘need’ among these ten that you consider to be a possible

incentive for home food production, do the following:

i. Describe a situation where you think this could be the incentive.

ii. State whether you think this incentive would mobilise a person into production,

and/or motivate a person to carry on producing year after year.

3. Think about ‘7 – Affiliation or the need to feel part of a group. Would you agree

that being part of an ongoing group of gardening friends could help motivate some

people to carry on planting their gardens? Because we realise that people want to

‘belong’, we may think of ways to make the Garden Learning Groups interesting and

meaningful. This can help to create that sense of belonging and shared experiences

– the good times and the hard times – which tie people together in a circle of

friendship.

4. Now you may also want to reflect on possible motivating factors for food

gardening related to 2 – bodily health; 5 – emotions; 6 – practical reason; 8 – other

species; and 10 – control over one’s environment.

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

22

5. Now think about the Human Capability (=Need=Motivating Factor) to play. Can

you see the value of building lots of fun into the Garden Learning Group sessions?

Fun and laughter is not only a very strong motivator, it is also recognised in medical

circles as the single most effective antidote to stress. (Science Daily. April 10, 2008)

Tools to help us differentiate between incentives

A number of tools and approaches can help the facilitator to better target advice

and interventions.

‘Household typologies’ can be developed to categorise people with similar

objectives. This approach was used for smallholder irrigation schemes, and is also

suitable to help target facilitation and intervention strategies for households with

different objectives in homestead farming.

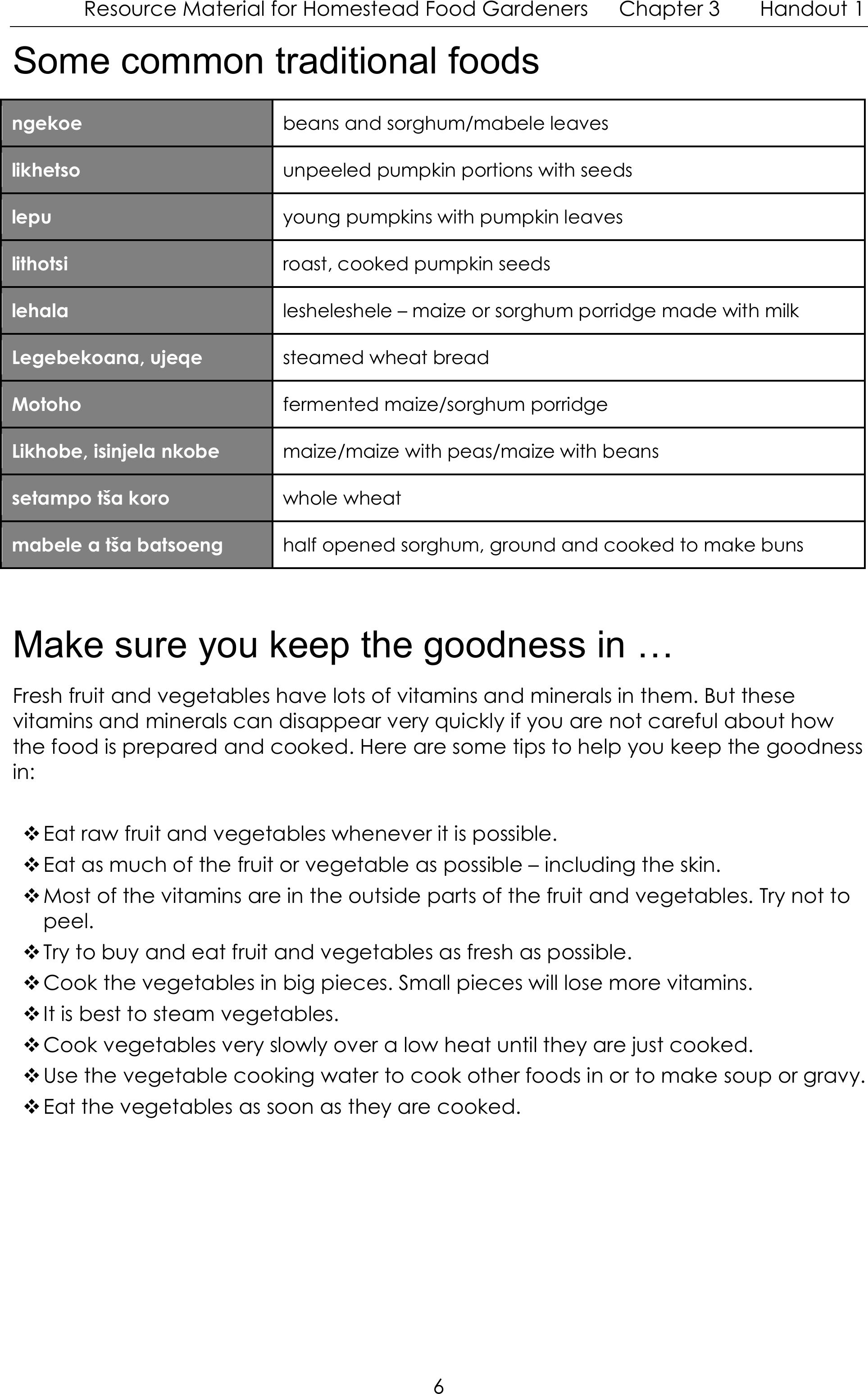

The Helicopter Planning method is a combined vision-building/action-

planning/self-monitoring process, which helps the household to think themselves

into a possible future, and to decide on a practical plan of action to achieve

their desired future through achievable and measurable steps. The method is

described in more detail in Chapter 2 of this document.

Both the ‘Helicopter Planning’ and the household typologies use scenario-based

planning to assess possibilities and their consequences, which can then also be used

to plan facilitation, training and intervention steps.

Later in the process, when the

facilitator starts working directly

with specific households, she can

use Helicopter Planning as a

tool to help each household to

get clarity about their own

objectives, and to plan their own

actions accordingly.

During initial scoping

(information gathering and

analysis) in a village, one gets a

broad idea of the types of

situations found in that village.

Household typologies or

categories can be developed at

that stage

Facilitator’s note:

Many people find the human

capabilities somewhat abstract and not

easy to understand. Do not get

discouraged if it does not make sense

to

y

ou immediatel

y

.

Introduction to the Resource Material

23

Some household typologies

The following case studies help us to think about the differences between

households’ situations. The facilitator needs to interpret what s/he sees and hears, in

order to plan effective facilitation strategies, and to do problem-solving in specific

cases.

Case study 1:

Ms Beauty Mbhele (Mantshalolo Village)

The situation:

Ms Mbhele (52) lives alone

with her two teenage

children (19 and 20 years)

and a younger severely

handicapped son. They

survive off her pension. She

is a traditional healer.

The homestead is small and

somewhat unkempt. She

had planted some maize in

her field, but her vegetable

garden was lying fallow at

the time.

Ms Mbhele paid a person

R800 that she had made

from selling potatoes she

had grown, to excavate

the hole for her

underground rainwater

harvesting tank. A

demonstration in trenchbed

production and channelling

rain water to the garden

was held at her home. The

family collected manure

and grass prior to the

demonstration.

Household Typology

summary:

People:

1 adult (active), 3

children; high

dependency ratio as

children are grown up

and could contribute,

and due to physical

disability of one child.

Income:

Pension and traditional

healing.

Cropping:

Maize, potatoes and

beans for household

use.

Livestock:

Some free range

chickens.

Intensification:

Rainwater harvesting

and vegetable

production.

Infrastructure:

Small homestead,

fenced, by vulnerable.

Human capacity:

Received some

training.

Possible enabling

interventions:

Assistance: Grants, food

support, health supporting

Vegetable production:

Intensification for household

use, to include fruit and small

livestock

Income replacement

interventions: For example

processing of food, grain

banks (for seed and food

security)

Assistance with productive

assets: fencing, water, fruit

trees, small livestock

Community services: Clinic,

crèches and school with

feeding schemes

Learning group support: For

sharing and supply of crops

(introduce new ideas), e.g.

potatoes, maize, beans,

sweet potatoes, onions,

tomatoes.

Supply of surplus produce to

local projects, where

possible,

Agricultural Water Use for Homestead Gardening Systems – Resource Material

24

A view of Miss Beauty Mbhele’s homestead.

Photo: E. Kruger, LIMA – DWAF, 2006

Nonhlanhla, a community facilitator for the NGO working in the area, interviews her. The

disused vegetable garden is in the background.

Introduction to the Resource Material

25

Case study 2:

Mr Michel Mbhele (Kayeka Village)

The situation:

This is a reasonably

sized homestead (with

one large and 2 small

dwellings) with 2

adults and 7 children.

Income consists of 1

child grant and Mrs

Mbhele sells snacks at

the nearby school.

They have received

some food production

training from LIMA and

Vukani. Rainwater is

presently harvested in

2 × 200 l drums and

used for watering

plants.

The property is

fenced. Fields above

and below the

homestead have

been planted to

maize and traditional

beans.

Household Typology

summary:

People:

2 adults (active), 7

children; high

dependency ratio.

Income:

grants and small business

activities.

Cropping:

maize and beans for

household use.

Livestock:

Some free range chickens,

kraal for cattle and goats.

Intensification:

Rainwater harvesting and

vegetable production.

Infrastructure:

Well developed

homestead, fenced fields

and garden, rainwater

harvesting tanks.

Human capacity:

Received training,

entrepreneurial ability.

Possible enabling interventions: